To characterise current management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Spain, as well as professional adherence to antiemetic guidelines.

Materials and methodsRetrospective observational study. A multicenter has been designed including 360 patient case files from 18 hospitals. The involvement of pharmacists and nurses was studied, and also indicators of structure, process, and selected outcomes previously recruited from antiemetic guidelines.

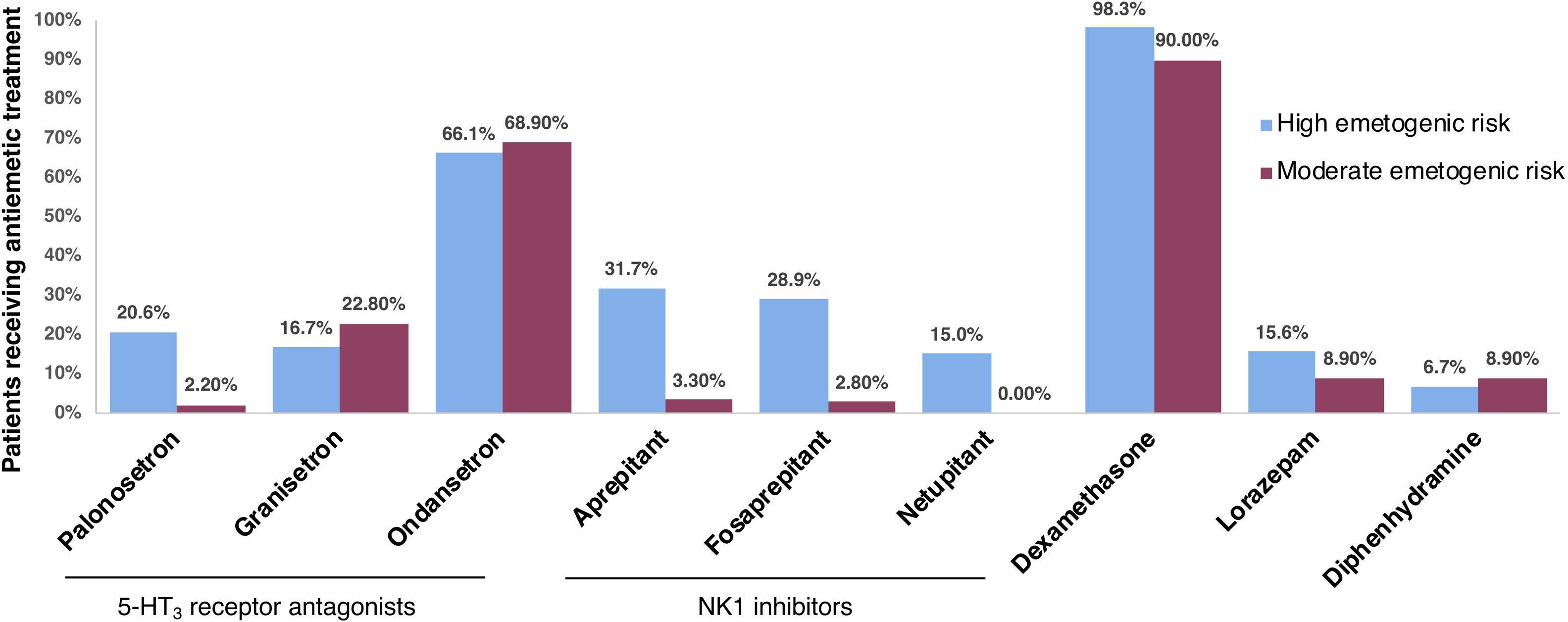

ResultsWe found 94.4% of hospitals used a written protocol for managing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and only 44.4% had educational programs for patients regarding this. Patients were prescribed antiemetic prophylactic treatment for delayed emesis in varying degree between highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (77.8% and 58.9%, respectively). Dexamethasone was the most prescribed antiemetic drug for patients receiving highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (98.3% and 90%, respectively), followed by ondansetron (68.9% and 95%, respectively). Nursing was more involved than pharmacy units in evaluating emetic risk factors in patients (64.7% vs 21.4%), and tracking symptom onset (88.2% vs 57.1%) and adherence to treatment (94.1% vs 28.6%). Pharmacy units were more involved than nursing in choosing the antiemetic treatment (78.6% vs 47%).

ConclusionsAlthough antiemetic guidelines were used by all hospitals, there were differences in management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Increased education directed towards patients and oncology professionals is needed to improve adherence.

Caracterizar la gestión actual en España de las náuseas y vómitos inducidos por quimioterapia y la adherencia profesional a las guías de antiemesis.

Material y métodosEstudio multicéntrico y observacional con análisis retrospectivo de los datos. Incluyó la información de 360 historias de pacientes de 18 hospitales. Se estudió el papel de enfermería y farmacia, y también varios indicadores de estructura, proceso y resultado extraídos previamente de las guías clínicas.

ResultadosEl 94,4% de los hospitales seguía un protocolo escrito para el manejo de las náuseas y vómitos inducidos por quimioterapia; el 44,4% tenía programas educacionales sobre este tema dirigidos a pacientes. La prescripción de profilaxis antiemética para emesis retardada varió entre quienes recibieron quimioterapia de alto o moderado riesgo emetógeno (77,8 y 58,9%, respectivamente). La dexametasona fue el antiemético más prescrito a pacientes que recibieron quimioterapia de alto o moderado riesgo emetógeno (98,3 y 90%, respectivamente), seguido de ondansetrón (68,9 y 95%, respectivamente). Las unidades de enfermería estuvieron más involucradas que las de farmacia en la evaluación de factores de riesgo asociados con la emesis en pacientes (64,7 vs. 21,4%), la monitorización de los primeros síntomas (88,2 vs. 57,1%) y el control del cumplimiento del tratamiento (94,1 vs. 28,6%). Las unidades de farmacia estuvieron más involucradas que las de enfermería en la elección del tratamiento antiemético (78,6 vs. 47%).

ConclusionesPese al uso de guías de antiemesis en los hospitales, se encontraron diferencias en la gestión de las náuseas y vómitos inducidos por quimioterapia. Es necesario un mayor énfasis en la educación de pacientes y profesionales oncológicos para mejorar el cumplimiento del tratamiento.

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is one of the most common side effects endured by cancer patients and has a severe impact on their quality of life.1 In 32% of patients, CINV may also result in delayed or discontinued chemotherapy, impacting treatment and compliance.2

Many organisations have developed guidelines for patient management regarding prevention of CINV, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO),3 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN),4 the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) jointly with the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC),5 and the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM).6 Guidelines are based on the emetogenic risk of the chemotherapeutic agents when administered without any antiemetic prophylaxis. This risk is classified as high (>90% risk of emesis, e.g., carboplatin), moderate (<30–90% risk), low (10–30% risk), or minimal (<10% risk). Guidelines also classify the side effects of chemotherapeutic agents based on the onset of nausea and vomiting, which can be acute (in the first 24h following chemotherapy administration); anticipatory (prior to chemotherapy administration and generally due to anxiety, sights, smells); and delayed (24h post-treatment, which can persist with high intensity for up to 72h post-treatment).1

Adherence to guidelines continues to be suboptimal,7–9 even though their use results in reduced incidence of CINV,10 and despite risk-model guided treatments improving CINV compared to physician's choice of treatment.11 Physicians are more likely to prescribe more aggressive treatment to younger patients with curable disease than to older patients with incurable disease, regardless of the emetogenic risk of the chemotherapy.12 A recent study in Spain showed that physicians overestimate the effectiveness of prophylactic antiemetic treatment, expecting a 10% lower percentage of patients with nausea and/or vomiting and a 21% higher drug effectiveness than those found.13 Based on these discrepancies, assessment of adherence to antiemetic guidelines and analysis of quality criteria by objective measures is, thus, necessary to understand the current challenges in treatment.

Use of antiemetic guidelines and the extent to which the recommendations reach the patient have not been studied in the context of Spanish healthcare. To address this knowledge gap, the Spanish Foundation for Excellence and Quality in Oncology (Fundación ECO) carried out this study to evaluate the quality of patient care in oncology departments in Spain regarding prevention of CINV and analyze the role that nursing and the pharmacy units play.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis is an observational, multicentric study involving 18 medical oncology departments (17 public, 1 private) from 7 autonomous regions of Spain. Each center retrospectively collected 20 consecutive medical records from patients that received care in the 15 days prior to September 1, 2017. A total of 360 patient medical records. The sample size met the minimum requirements of the Achievable Benchmarks of Care method,14 and allowed indicators to be estimated with a precision of 0.21 points, based on a two-tailed test and a power of 81% (Sample Power, SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). This study was carried out between May 23, 2018 and December 23, 2018.

The coordinating committee—comprising the authors S M-A, J C-C, and Y E-A, from 3 different hospitals—selected quality criteria in the form of structure, process, and outcome indicators among the recommendations present in the guidelines developed by: SEOM,6 ASCO,3 NCCN,4 and MASCC/ESMO.5 Each center evaluated 20 patient case files and recorded in a grid their responses (“yes”, “no”, or “not applicable”) to the use of the selected indicators of structure, process, and outcome. The questionnaires were completed by 18 oncologists, 17 nurses, and 14 pharmacists. During this study, a website was available to the participating researchers for communication, reviewing the protocol and other materials, and providing aggregated patient data.

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and carried out following the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda (Spain).

Patient data collectionThe criteria used for patient medical record selection were: (1) patient visit in the 15 days prior to September 1, 2017; (2) patient received chemotherapy treatment classified as having either high (>90% frequency) or moderate (>30–90% frequency) emetogenic risk; (3) availability of information regarding use of antiemetic treatment during the first cycle of first line of chemotherapy treatment; and (4) patient received chemotherapy as a single daily dose during the first cycle.

Each participating center collected data from 10 patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy and 10 patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Aggregated data were collected from the most commonly used antiemetic drugs. Aggregated patient data was used and, thus, no informed consent was required.

Structure indicatorsThe indicators of structure used where: (1) type of hospital or center (public, private, or mixed); (2) number of patients per month that receive chemotherapy; (3) existence of a written protocol for prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy; (4) participation of the pharmacy unit in creating protocols for prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy; (5) existence of an emesis diary for patients undergoing chemotherapy; (6) existence of educational programs directed towards patients; (7) guidelines followed for treating emesis; and (8) availability of a specific consultation service for oncology patients in the pharmacy unit.

Process indicatorsTen consecutive files of patients receiving chemotherapy were used to evaluate process indicators: 5 indicators were used for patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy; 4 for those receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. To assess the applicability of each indicator, investigators determined in each record whether the indicators were fulfilled (“yes”, “no”, or “not applicable”). If an indicator had been considered not applicable in more than 10% of cases, it was not deemed acceptable for its generalised use. The average percentage of fulfilment of the process indicators was calculated for each participating center, with those that were not applicable being excluded.

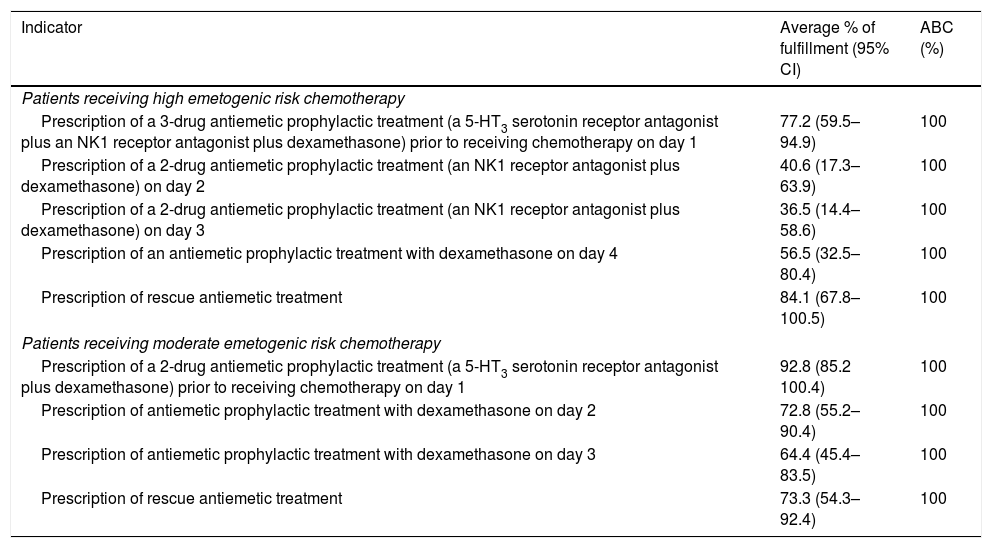

The process indicators used for analyzing data from patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy were the amount of patients that were prescribed: (1) a 3-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (a 5-HT3 [serotonin] receptor antagonist plus a neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) prior to receiving chemotherapy on day 1; (2) a 2-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (an NK1 receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) on day 2; (3) a 2-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (an NK1 receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) on day 3; (4) an antiemetic prophylactic treatment with dexamethasone on day 4; and (5) rescue antiemetic treatment.

The process indicators used for analyzing data from patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy were the amount of patients that were prescribed: (1) a 2-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (a 5-HT3 [serotonin] receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) prior to receiving chemotherapy on day 1; (2) antiemetic prophylactic treatment with dexamethasone on day 2; (3) antiemetic prophylactic treatment with dexamethasone on day 3; and (4) rescue antiemetic treatment.

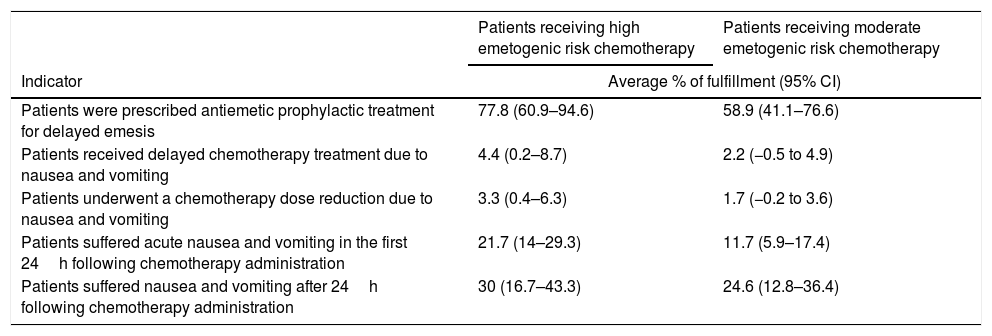

Outcome indicatorsOutcome indicators were evaluated in patients based on the emetogenic risk of their prescribed chemotherapy treatment. The indicators used were the percentage of patients that: (1) were prescribed antiemetic prophylactic treatment for delayed emesis; (2) received delayed chemotherapy treatment due to nausea and vomiting; (3) underwent a chemotherapy dose reduction due to nausea and vomiting; (4) suffered acute nausea and vomiting in the first 24h following chemotherapy administration; and (5) suffered nausea and vomiting after 24h following chemotherapy administration. Outcome indicators that were deemed “not applicable” were not considered to be fulfilled and, thus, their applicability was not assessed.

Other indicatorsOther descriptors used were the percentage of patients receiving a chemotherapy regime that included carboplatin, and those receiving treatment with palonosetron, granisetron, ondansetron, aprepitant, fosaprepitant, netupitant, dexamethasone, lorazepam, or diphenhydramine.

Indicators of involvement of nursing and the pharmacy unit in patient careThe indicators used were the percentage of these units that: (1) evaluated emetic risk factors in patients receiving chemotherapy; (2) asked the patient whether they had experienced nausea and vomiting and when these symptoms had appeared; (3) participated in choosing the antiemetic prophylactic treatment; (4) tracked adherence to the antiemetic prophylactic treatment; and (5) used an emesis diary to track CINV.

Achievable Benchmarks of CareThe Achievable Benchmarks of Care (ABCs) technique, developed by the University of Alabama at Birmingham,14 was used to analyze indicators of process. The pared-mean method creates benchmark levels and allow to compare all hospitals with the average performance of the top 10%. Bayesian estimators for adjustment of fulfillment were used to rank the centers.

Statistical analysisMedical personnel from E-C-Bio reviewed the patient data introduced by the investigators participating in this study to ensure they were complete and coherent. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS. A descriptive analysis was used for the frequency distribution of the qualitative variables, and mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, and 95% confidence intervals were analyzed for the quantitative variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests, and quantitative variables were analyzed with Student's t or Mann–Whitney U tests. A P value<0.05 was considered significant and was corrected according to the variables included in multiple regression equations.

ResultsStructure indicatorsSeventeen of the centers in this study were public; 1 was private. They received a monthly average of 1000 (CI 95% 649–1351) patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment.

Out of all centers, 94.4% (17/18) had a written protocol for prevention of CINV. In 77.8% (14/18), the pharmacy unit participated in developing a protocol for handling nausea and vomiting in patients receiving chemotherapy. Only 22.2% (4/18) of centers had an emesis diary for the patients receiving chemotherapy. Educational programs for patients regarding nausea and vomiting were available in 44.4% (8/18) of centers. Eleven centers (61.1%) had a specific consultation service for oncology patients in the pharmacy unit.

Several clinical guides for emesis were used in the oncology departments that participated in this study: 16.7% (3/18) used only one guide as reference, either the one developed by the hospital's oncology department or the one developed by ASCO; 16.7% (3/18) of centers used 2 guides, SEOM and MASCC/ESMO; 55.6% (10/18) used 3 guides; and 11.1% (2/18) of centers used 4 guides, SEOM, MASCC/ESMO, NCCN, ASCO. In total, 83.3% (15/18) of centers used SEOM, 66.7% (12/18) used MASCC/ESMO, 61.1% (11/18) used NCCN, and 38.9% (7/18) used ASCO's guidelines.

Process indicatorsDue to the varying emetogenic potential of chemotherapy regimens, data was gathered from two patient groups receiving either highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. In the highly emetogenic group, 2 of the 5 indicators surpassed the established 10% limit for non-applicability but they were included due to their proximity to the threshold: “2-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (an NK1 receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) on day 3” (10.6%), and “antiemetic prophylactic treatment with dexamethasone on day 4” (11.1%). In the moderately emetogenic group, applicability of all process indicators was considered acceptable. Fulfilment of the process indicators was calculated for each center and benchmarked against the top 10% of centers, for which ABC was of 100% (Table 1). Among patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy, the indicator with the highest rate of fulfilment was “rescue antiemetic prescription” (84.1%). In the case of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy, the highest rate of fulfilment regarded the prophylactic 2-drug combination prior to chemotherapy on day 1 (92.8%).

Achievable benchmarks of care of process indicators.

| Indicator | Average % of fulfillment (95% CI) | ABC (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients receiving high emetogenic risk chemotherapy | ||

| Prescription of a 3-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (a 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonist plus an NK1 receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) prior to receiving chemotherapy on day 1 | 77.2 (59.5–94.9) | 100 |

| Prescription of a 2-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (an NK1 receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) on day 2 | 40.6 (17.3–63.9) | 100 |

| Prescription of a 2-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (an NK1 receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) on day 3 | 36.5 (14.4–58.6) | 100 |

| Prescription of an antiemetic prophylactic treatment with dexamethasone on day 4 | 56.5 (32.5–80.4) | 100 |

| Prescription of rescue antiemetic treatment | 84.1 (67.8–100.5) | 100 |

| Patients receiving moderate emetogenic risk chemotherapy | ||

| Prescription of a 2-drug antiemetic prophylactic treatment (a 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone) prior to receiving chemotherapy on day 1 | 92.8 (85.2 100.4) | 100 |

| Prescription of antiemetic prophylactic treatment with dexamethasone on day 2 | 72.8 (55.2–90.4) | 100 |

| Prescription of antiemetic prophylactic treatment with dexamethasone on day 3 | 64.4 (45.4–83.5) | 100 |

| Prescription of rescue antiemetic treatment | 73.3 (54.3–92.4) | 100 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ABC, achievable benchmark of care; NK1, neurokinin 1; 5-HT3, 5-hydroxytryptamine.

In the highly emetogenic chemotherapy group (Table 2), the indicator with the highest rate of fulfilment was “Patients that were prescribed antiemetic prophylactic treatment for delayed emesis” (77.8%) and the one with the lowest rate was “Patients that underwent a chemotherapy dose reduction due to nausea and vomiting” (3.3%). In the moderately emetogenic chemotherapy group (Table 2), the indicator with the highest rate of fulfilment was “Patients that were prescribed antiemetic prophylactic treatment for delayed emesis” (58.9%), and the one with the lowest rate was “Patients that underwent a chemotherapy dose reduction due to nausea and vomiting” (1.7%).

Fulfillment of outcome indicators.

| Patients receiving high emetogenic risk chemotherapy | Patients receiving moderate emetogenic risk chemotherapy | |

|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Average % of fulfillment (95% CI) | |

| Patients were prescribed antiemetic prophylactic treatment for delayed emesis | 77.8 (60.9–94.6) | 58.9 (41.1–76.6) |

| Patients received delayed chemotherapy treatment due to nausea and vomiting | 4.4 (0.2–8.7) | 2.2 (−0.5 to 4.9) |

| Patients underwent a chemotherapy dose reduction due to nausea and vomiting | 3.3 (0.4–6.3) | 1.7 (−0.2 to 3.6) |

| Patients suffered acute nausea and vomiting in the first 24h following chemotherapy administration | 21.7 (14–29.3) | 11.7 (5.9–17.4) |

| Patients suffered nausea and vomiting after 24h following chemotherapy administration | 30 (16.7–43.3) | 24.6 (12.8–36.4) |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

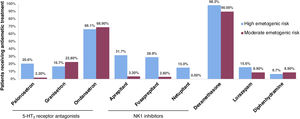

Chemotherapy that included carboplatin was administered to 35.6% (95% CI, 17.5–53.6) of patients in the highly emetogenic group, and 32.8% (95% CI, 15–50.6) in the moderately emetogenic group. Fig. 1 shows the percentage of patients that received antiemetic treatment with a series of drugs. In both high and moderate emetogenic risk groups, the most prescribed antiemetic treatment was dexamethasone (98.3% and 90%, respectively), followed by ondansetron (68.9% and 95%, respectively).

Involvement of nursing and pharmacy units in patient careWe found that nursing and the pharmacy units of 64.7% (11/17) and 21.4% (3/14) of centers, respectively, evaluated the emetic risk factors in patients receiving chemotherapy; 88.2% (15/17) and 57.1% (8/14) asked the patient whether they had nausea and vomiting and when these symptoms had appeared; 47% (8/17) and 78.6% (11/14) participated in choosing the antiemetic prophylactic treatment; 94.1% (16/17) and 28.6% (4/14) tracked adherence to the antiemetic prophylactic treatment; and 35.3% (6/17) of nursing units and none of the pharmacy units used an emesis diary to track the first sign of nausea and vomiting following chemotherapy.

DiscussionIn this study, we analyzed the use of antiemetic guidelines in 18 hospitals in Spain and we evaluated indicators of structure, process, and outcome in these centers. We used ABCs to compare centers regarding the process indicators in order to evaluate the degree to which recommendations were followed; we found that all indicators had an ABC of 100%, indicating that all the recommendations were achievable.

Underuse of antiemetic guidelines impacts treatment and quality of life of patients. All hospitals in this study followed at least one guideline, with variability between them. It has been shown that inpatient chemotherapy treatment (compared to outpatient) and age predict a lower risk of antiemetic underuse.8,15 Several studies have found that patients receive antiemetic treatment that does not comply with antiemetic guidelines, especially in the delayed phase.7,8,16 Underuse of these guidelines has been linked, in some cases, to the lack of use of NK1 receptor antagonists,10,15,17 such as aprepitant, fosaprepitant, and netupitant. In our study, use of these antagonists was much higher in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy than in those with moderately emetogenic chemotherapy.

Healthcare professionals must educate patients and follow strategies that identify the risk factors for CINV and address them to minimise impact on patients’ quality of life and treatment. While oncologists and nurses estimate or report that approximately a third of patients do not self-administer antiemetics correctly and miss or delay doses, self-reporting from patients shows this lack of adherence could be as high as 62%.18,19 Educating the patients in the importance of adherence is key in chemotherapy treatment being successfully carried out. In this study, we found that only 44.4% of hospitals had educational programs in place for patients regarding nausea and vomiting. Strategies directed towards improving patient education increase adherence20,21 and, in particular, a recent study also showed this in the case of adherence to antiemetic treatment.22 Thus, in the context of Spanish healthcare, programs targeting patient education and communication with oncology professionals are necessary.

Throughout chemotherapy treatment, oncologists evaluate the toxicity that patients may have experienced in the previous cycle, and may reduce or delay the next one. Although oncologists prescribe chemotherapeutic and antiemetic treatments, nurses play an important role in prevention and management of CINV. In this study, we found that nursing was highly involved in tracking adherence to the prophylactic antiemetic treatment and evaluating patient risk factors, among others. In a study involving several countries, a third of nurses reported their knowledge of CINV was fair to poor, and only 35% were confident in their ability to manage CINV.23 Nurses have also reported low adherence to antiemetic guidelines, mainly due to physician preference.16 It is necessary to improve training of oncology nurses to ensure that patient risk factors are taken into account when establishing treatment, that treatment is followed, and that emesis is appropriately tracked. On this note, an approximate third of centers (35.3%) used a diary to keep track of CINV in their patients. Previous studies have shown that using a diary for this purpose helps clinical staff adjust antiemetic therapy and improves patient control and response to CINV.24 Increased attention should be given to the use of a diary to help accurately and objectively assess CINV and improve communication between patients and healthcare professionals.

Pharmacists also play a role in improving adherence to CINV guidelines and assist with patient management. Collaboration between pharmacists and oncologists on the management of CINV is shown to have positive results,25,26 with the involvement of the pharmacy unit reducing delayed CINV and improving adherence to treatment.27 In this study, we found that pharmacists were less involved than nurses in the care of patients taking antiemetics, with the exception of making decisions on treatment. In particular, pharmacists had a much lower involvement in the evaluation of emetic risk factors. Strategies should be implemented to increase the active participation of nursing and pharmacy units in the management of these patients. Notably, pharmacists in Spain are not allowed to prescribe medication. Additionally, the use of electronic records and an electronic system connecting all hospital units could improve nursing and pharmacy units’ communication and involvement in cancer patient care.

The main limitations of this study are related to its cross-sectional design, which precludes establishing causality for any of the parameters evaluated. Additionally, the use of aggregated patient data does not allow to establish comparisons between variables, and only mean values and global percentages are used. This study also has several strengths: the patient population covers several regions of Spain, increasing the external validity; and the ABC methodology was used, providing an objective, quantifiable measure of excellence that can be achieved.

Policies directed towards educating healthcare professionals on the importance of adherence to antiemetic guideline recommendations are needed in order to improve patient care. Healthcare professionals should be encouraged to follow guidelines and work in multidisciplinary teams. Additional resources should be allocated to educating patients and improving communication between them and the multidisciplinary team of oncology professionals.

Ethics approvalThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda (Spain).

Consent to participateInformed consent was not required due to the data being aggregated.

FundingTesaro Bio Spain S.L.U funded this study in the form of a grant to Fundación ECO.

Each participating center received compensation for their contribution.

Conflicts of interestThe authors received personal fees from Fundación ECO for their time and effort developing this study.

The authors thank all the participating nursing and pharmacy teams; Begoña Soler for coordinating the study on behalf of E-C-Bio and conducting the statistical analysis; and Angela Rynne Vidal, PhD, for providing writing and editing support.