Medication adherence is an important indicator of quality in healthcare, and non-adherence is associated with increased healthcare costs, hospital admissions, re-admissions, and decline in health outcomes. Despite the availability of medication to control and avoid adverse health outcomes, adherence to medications among asthma patients varies between 40% and 60%. The objective of this study is to evaluate the effects of asthma medication adherence on healthcare services.

Material and methodsThis cross-sectional study is based on insurance claims data for Medicaid patients primarily diagnosed with asthma during 2015–2016. A regression analysis was performed to examine the relationship between control and rescue medication adherence with healthcare use (hospital admissions and re-admissions, clinic visits, and emergency department visits), as well as patient demographics (age, gender, and estimated income).

ResultsThis study found a control medication adherence of 82%. Patients with high rescue medication adherence had fewer emergency department visits (p=.0004) and inpatient admissions (p=.0303). Patients with more than 4 clinic visits had higher rescue medication adherence. Older and low-income patients had higher 30-day re-admissions. Males and low-income patients had more emergency visits.

ConclusionsThese results provide evidence that certain populations (older, low-income, and male) may benefit from additional education on monitoring and controlling asthma. This may reduce costlier healthcare services use in favor of less expensive physician visits and education programs.

La adherencia a la medicación es un indicador importante de la calidad de la atención sanitaria, asociándose la no adherencia al incremento de los costes sanitarios, los ingresos hospitalarios, los re-ingresos, y el descenso de los resultados médicos. A pesar de la disponibilidad de la medicación para controlar y evitar los resultados médicos adversos, la adherencia a la medicación entre los pacientes de asma oscila entre el 40 y el 60%. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar los efectos de la adherencia a la medicación para el asma en los servicios sanitarios.

Material y métodosEste estudio transversal se basa en los datos de las reclamaciones de seguros para pacientes de Medicaid con diagnóstico principal de asma durante el periodo 2015-2016. Se realizó un análisis de regresión para examinar la relación entre la adherencia a la medicación, de rescate y de control, y el uso sanitario (ingresos y re-ingresos hospitalarios, visitas clínicas, y visitas al servicio de urgencias), así como los datos demográficos de los pacientes (edad, sexo, e ingresos estimados).

ResultadosEste estudio encontró una adherencia a la medicación de control del 82%. Los pacientes con una alta adherencia a la medicación de rescate reflejaron una tasa menor de visitas al servicio de urgencias (p=0,0004) e ingresos hospitalarios (p=0,0303). Los pacientes con más de 4 visitas clínicas tuvieron mayor adherencia a la medicación de rescate. Los pacientes mayores y con rentas bajas reflejaron una tasa superior de re-ingresos a los 30 días. Los pacientes varones y con rentas bajas reflejaron una tasa superior de visitas al servicio de urgencias.

ConclusionesEstos resultados aportan evidencia de que ciertas poblaciones (pacientes mayores, con rentas bajas, y varones) pueden beneficiarse de una formación adicional sobre supervisión y control del asma. Esto podría reducir el uso de los servicios sanitarios costosos, en favor de visitas médicas más económicas y programas educativos.

Approximately 117 million people in the United States live with at least one of 10 common chronic conditions such as asthma.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2011), 1 in 12 people have asthma. Most asthma hospitalizations are considered avoidable, as the symptoms can be prevented and controlled with the appropriate use of medications, proper asthma management at home and outpatient care.2 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimated that 11% of hospital readmissions occur due to medication non-adherence and the resulting costs are estimated to be $100–$289 billion annually.3

Medication adherence is defined as “the extent to which a patient's behavior corresponds with recommendations from a health care provider”.9 Approximately one-half of patients in the United States do not take their medications as prescribed.9 Medication non-adherence not only affects the patient, but it also has severe economic impact and is a major cause of concern for healthcare providers, organizations and payers alike. In particular, for asthma patients, medication non-adherence has been associated with mortality, increased direct and indirect costs, additional healthcare resource utilization, reduced quality of life and increased asthma symptoms.10–13 Despite the known benefits of using control medications on a daily basis, low adherence rates have repeatedly been reported across studies, with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS, a preferred long term asthma medication) adherence ranging from 40% to 60%.14–16 Non-adherence to asthma medications among children can cause excessive wheezing and variability in pulmonary function, limiting daily activities, exacerbations, deterioration of health, need for excessive urgent care, hospitalizations, and death in some cases.17

Asthma medication adherence has been associated with reduced exacerbations and hospitalizations.25 A study reported that hospitalizations, readmissions and even mortality were lower among patients that are medication adherent.26 Another study regarding recurrence risk after an emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization and delay in filling asthma controller medication reported an increase in asthma related-ED visits or inpatient stay when there was a delay in initiation of controller medication.27 Thus, there is plenty of evidence in the literature on the association between medication adherence and hospital utilization. This paper investigates the relationship between medication adherence and different types of hospital visits as well as readmissions among asthma patients under Medicaid.

In order to control their illnesses, patients with chronic conditions take necessary medications throughout their life. Tracking or measuring medication adherence among the chronically ill is therefore important. Currently, there is no gold standard for measuring medication adherence. Selection of an appropriate method depends on various factors such as the definition of adherence used, resources available, characteristics being evaluated, patient population, time assessment, and ethical/legal considerations in contacting or interviewing the patient.18 The aim of this study is to investigate the association between medication adherence and hospital utilization among Medicaid insured asthma patients in Louisiana by testing the following hypotheses.

- ∘

H1: Asthmatic patients with lower level of medication adherence, as measured by Medication Possession Ratio (MPR), have more emergency visits, including (emergency department visits, inpatient stay and hospital readmission at various intervals i.e. 30-day and 90-day).

- ∘

H2: Asthmatic patients that attend at least 4 scheduled office visits have higher levels of medication adherence.

- ∘

H3: Patients prescription adherence and emergency visit rates will differ by demographic groups (age, gender and income level).

- ∘

H4: Readmission rates of asthma patients will be significantly different from readmission rates of non-asthmatic group.

Data for this study was sourced from a healthcare insurance provider based in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The company provides health coverage to Medicaid or LaCHIP (Louisiana Children's Health Insurance Program) qualified people through state's Healthy Louisiana program and links Medicaid recipients to primary care providers, pharmacies and case managers. In advance of this study the Institutional Review Board at Louisiana State University reviewed and approved the study. The data provided by Louisiana Health Connections (LAHCA), a healthcare insurance provider, was de-identified based on the LAHCA compliance policy and patient privacy guidelines (HIPAA) for de-identification of data, in particular for underage patients.

Asthma drug classificationAsthma medications are classified as “rescue” or quick relief or short-term medications, and “control” or preventive or long-term medications.4 Rescue medications are often referred to as “bronchodilators” and are used in case of acute asthma attacks for quick relief, and their effect lasts 4–6h.5 These medications are not recommended to be used very often due to their reported side effects such as muscle tremor, rapid heartbeat and restlessness.6 Control medications are used on a daily basis for patients with persistent asthma to reduce airway inflammation and decrease acute exacerbations. The effects of these medications last 12h or more.5,7 Inconsistency in adhering to these medications may result in exacerbations and may result in physicians believing that the patient is adherent and needs an increase or change in medications.8 Thus, it is critical for the patient to have a good understanding of the reasons for taking medications as prescribed, in particular for patients with asthma.

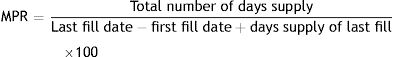

The selected method of measuring medication adherence in this study is known as Medication Possession Ratio (MPR). MPR is calculated as the sum of the days’ supply obtained during the study period divided by the total number of days in this time period plus the last fill days supply. MPR measures adherence by assessing medication availability and determining skipped or discontinued medications.19

The MPR approach to adherence measurement has a few drawbacks. It may overestimate medication adherence as it does not address overuse that occurs when patients buy early refills of their medication causing an overlap and inflation in the resulting value.20 However, MPR is a widely used and accepted method to measure medication adherence in the literature and in practice for various illnesses.21,22 Researchers consider patients with MPR lower than 80% as non-adherent.23,24 MPR was calculated for control medication and rescue medications separately for each patient for this study.

Study populationThe study population consists of Medicaid patients of all ages with primary or secondary diagnosis of asthma and who were insured during January 1, 2015–December 31, 2016. The patients are covered under 6 insurance coverages: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Medicaid Expansion, Supplemental security income Non-dual (SSI Non-Dual), Foster care, Behavioral health and Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision code (ICD 9) 493.XX and tenth revision code (ICD 10) J45.XX, and the list of asthma medications with 9-digit National Drug Codes (NDC) within each asthma drug class (control and rescue medications) were used to identify members with asthma. Patients were eligible for study inclusion if they met all of the following criteria: two or more pharmacy claims for asthma control medication; asthma patients with a least one primary care claim (e.g. physician office visit); continuously eligible and enrolled in health coverage during the study period. In order to have a baseline on readmissions a group of non-asthmatic members were evaluated. A data set containing 970 non-asthmatic members (with at least one inpatient admission) was collected randomly, as a control group, to compare readmission rates among asthmatic and non-asthmatic groups.

Statistical analysis- 1.

Descriptive analysis (numbers, percentages, means, standard deviations etc.) was conducted on the sample to summarize the data collected for the study.

- 2.

A Pearson correlation analysis was performed to discover the relationship/direction of relationship between office visits, emergency visits, inpatient admissions with control and rescue medication adherence.

- 3.

A two sample t-test was performed to see if asthmatic patients that attend at least 4 scheduled office visits have higher levels of medication adherence.

- 4.

A multiple regression analysis was performed to see if patients’ prescription adherence and medical visit rates differed by demographic groups (age, gender and income level). Multiple regression analysis with backward elimination was performed in order to explore the relationship between each of the dependent variables: control medication adherence, type of medical visits (including, inpatient admits, emergency department visits, 30 and 90-day readmissions), and independent variables: age, gender, income. Prior to conducting the regressions, the independent variables were checked for correlations, and no collinearity was found.

- 5.

A two sample t-test was conducted to understand if readmissions characteristics are similar among asthma patients and the non-asthmatic group. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) were calculated to determine the relative probability of readmissions for the groups.

An α=0.05 was used for the statistical analysis.

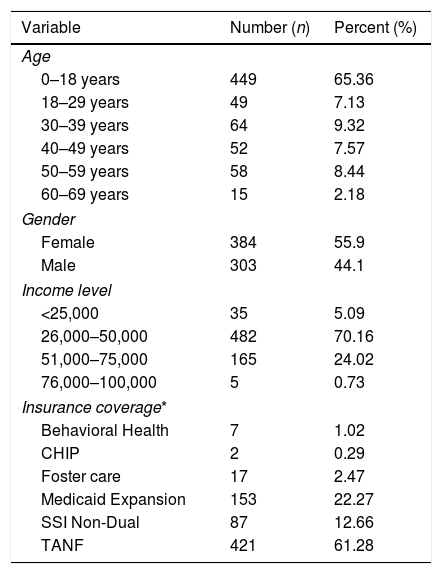

ResultsCharacteristics of patientsSample description of asthma patientsOut of the 2085 asthma patients with continuous insurance eligibility for the two-year study period (January 2015–December 2016), 687 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. A summary of descriptive statistics for the study population is shown in Table 1. Most patients (65%, 449) are considered minors, under the age of 18. The income distribution shows that 70% of the patients had a median household income of $25,000–$50,000 per year.

Patient demographics of asthma patients (n=687).

| Variable | Number (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 0–18 years | 449 | 65.36 |

| 18–29 years | 49 | 7.13 |

| 30–39 years | 64 | 9.32 |

| 40–49 years | 52 | 7.57 |

| 50–59 years | 58 | 8.44 |

| 60–69 years | 15 | 2.18 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 384 | 55.9 |

| Male | 303 | 44.1 |

| Income level | ||

| <25,000 | 35 | 5.09 |

| 26,000–50,000 | 482 | 70.16 |

| 51,000–75,000 | 165 | 24.02 |

| 76,000–100,000 | 5 | 0.73 |

| Insurance coverage* | ||

| Behavioral Health | 7 | 1.02 |

| CHIP | 2 | 0.29 |

| Foster care | 17 | 2.47 |

| Medicaid Expansion | 153 | 22.27 |

| SSI Non-Dual | 87 | 12.66 |

| TANF | 421 | 61.28 |

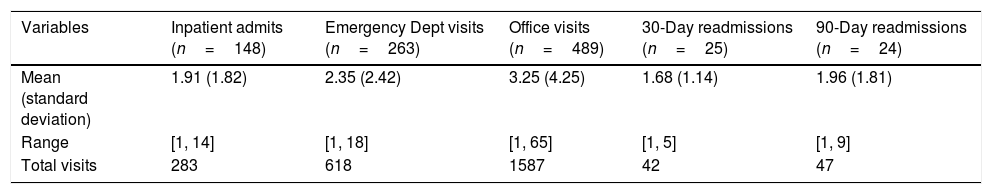

Table 2 summarizes patients within the study population that required inpatient admissions, emergency department visits, office visits, 30-day or 90-day readmissions. Of 687 asthma patients, 148 patients had inpatient admissions, 263 had emergency visits, 489 had office visits, 25 had 30-day readmissions and 24 had 90-day readmissions.

Description of patients requiring inpatient, emergency department, office visits, 30-day or 90-day readmissions within the total study population.

| Variables | Inpatient admits (n=148) | Emergency Dept visits (n=263) | Office visits (n=489) | 30-Day readmissions (n=25) | 90-Day readmissions (n=24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (standard deviation) | 1.91 (1.82) | 2.35 (2.42) | 3.25 (4.25) | 1.68 (1.14) | 1.96 (1.81) |

| Range | [1, 14] | [1, 18] | [1, 65] | [1, 5] | [1, 9] |

| Total visits | 283 | 618 | 1587 | 42 | 47 |

A group of 972 non-asthmatic Medicaid members with the same insurance company for the study period were randomly selected i.e., none of these members had been diagnosed with asthma. Of the 972 members only 90 members had inpatient admissions. Therefore 90 non-asthmatic patients were selected to be compared against asthma patients with inpatient admissions (n=148), as a control group (e.g. non-asthmatic group). Reasons for inpatient admissions ranged from acute illnesses, chronic illnesses, and behavioral health related disorders.

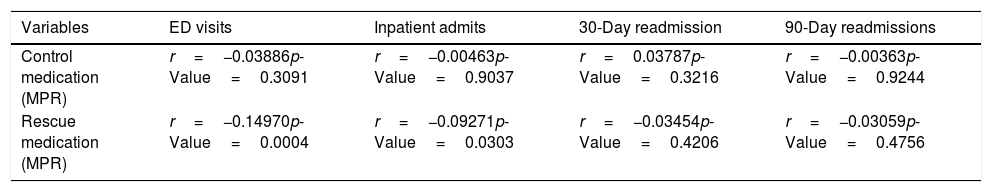

Relationship between medication adherence and healthcare useED visits, inpatient admits, 30-day readmission, and 90-day readmission were not significantly correlated with control medication adherence (Table 3). Out of 687 asthma patients that took control medications, 546 patients also took rescue medications as needed. Rescue medication adherence refers to patients that took rescue medications at some point during the 2 years. The correlation matrix in Table 3, evaluates the relation between all the hospital visit types and rescue medication adherence. A significant negative relationship exists between emergency department visits (r=−0.14970, p=0.0004) and inpatient admits (r=−0.09271, p=0.0303) with rescue medication adherence i.e. patients with higher rescue medication adherence have fewer emergency department and inpatient admits.

Correlation matrix for emergency, inpatient admits, 30- and 90-day readmissions and control & rescue medication adherence for asthma patients (n=687).

| Variables | ED visits | Inpatient admits | 30-Day readmission | 90-Day readmissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control medication (MPR) | r=−0.03886p-Value=0.3091 | r=−0.00463p-Value=0.9037 | r=0.03787p-Value=0.3216 | r=−0.00363p-Value=0.9244 |

| Rescue medication (MPR) | r=−0.14970p-Value=0.0004 | r=−0.09271p-Value=0.0303 | r=−0.03454p-Value=0.4206 | r=−0.03059p-Value=0.4756 |

Pearson correlation coefficients, N=687 Prob>|r| under H0: Rho=0.

An independent samples t-test was performed to evaluate if there was significant difference between control and rescue medication adherence behavior between patients with more than 4 office visits and patients with less than 4 office visits. The results reported that there was no significant difference in control medication adherence in patients with more than 4 office visits (M=81.5, SD=25.9) and patients with less than 4 office visits (M=82.5, SD=26.3) conditions; t=0.41, p=0.6853. However, patients with more than 4 office visits (M=52, SD=33.3) have significantly different rescue medication adherence compared to patients with less than 4 office visits (M=61.9, SD=34.6) conditions; t=2.8, p=0.0063.

Influence of demographics on medical visits and control medication adherenceThe results of regression analysis (reported in Table 4) showed that emergency visits are influenced significantly by gender (p=0.0387) and income (p=0.0430), with males being more likely to have emergency visits, and emergency visits being higher with lower income individuals. Thirty-day readmissions are influenced by age (p=0.0616) and income (p=0.0662) at a level approaching significance, with increasing age and lower income levels increasing the probability of readmission. Control medication adherence, inpatient admits, and 90-day readmissions were not influenced significantly by any demographic variable (p>0.1488).

Readmission rates for asthma patients and non-asthmatic groupsReadmissions within 30-days and 90-days among asthma patients and the non-asthmatic group (e.g. control group) are significantly different (p=0.0005 and p=0.050, respectively). The odds ratios indicate that asthma patients have lower chances of 30-day [OR 0.117, 95% CI (0.062, 0.218)], and 90-day [OR 0.260, 95% CI (0.123, 0.551)] readmissions compared to the non-asthmatic group.

DiscussionThe current study explored the relationship between medication adherence and healthcare utilization (including inpatient visit, office visit, emergency department visit, 30-day hospital readmission and 90-day readmission) among Medicaid insured asthma patients. Lower rates of inpatient admits and visits to the emergency department of asthmatic patients were significantly correlated with higher rescue medication adherence. Therefore, patients that take their rescue medication tend to have fewer emergency visits and inpatient admits.

Even though patients take rescue medication during attacks, negligence in taking control medication, especially among patients with severe asthma can prove harmful. Previous studies reported that adherence to control medications among asthma patients varies between 40% and 60%, with 80% and above being the threshold of good medication adherence.28 Average control medication adherence for the current study population was 82%, with 474 out of 687 (i.e., 69%) of the patients adhering to their control medications. Hence, the current study population is in the threshold of good medication adherence as defined in previous studies. 283 patients (41%) had inpatient admissions and 7% of these patients were readmitted into the hospital within 30 and 90 days. Although lower level of control medication adherence was expected to affect all types of visits to the hospital, results showed otherwise with no correlations being statistically significant. This could have been the result of the sample data tendency toward good control medication adherence.

Patients with chronic conditions are often managed or given instruction on medications at their primary care physician's (PCP) office. The results however showed that patients with more than 4 office visits do not have higher levels of control medication adherence. A possible reason for this result could be the lack of data on the patient's medical reason for the office visits (i.e., if the visit was scheduled or unscheduled because of worsened conditions). Knowing the reason for office visits would help show the relationship among regular scheduled office visits and patients adherence to their prescribed control medication. This is in line with the result of another t-test for patients taking rescue medications which showed that patients with more than 4 office visits tend to have higher levels of rescue medication adherence. This might be an indication that these office visits are due to worsened conditions requiring rescue medication because the patient condition cannot be improved with their controller medications. However, increased rescue medication adherence is associated with fewer emergency visits and inpatient admits, suggesting that while not ideal, using the rescue medications prevents more costly types of healthcare utilization.

Results showed that men and low income asthma patients tend to have more ED visits, and 30-day readmissions are higher among older and low income patients. These results can be used to monitor certain populations that need more care such as older, low income or male patients in this case, to reduce unnecessary hospital utilization and hospital bills.

The strengths of this study include a large sample size of patients and the comprehensiveness of the data to cover nearly all types of healthcare (prescription use, physician office visits, hospital utilization, and readmissions). Using multiple types of healthcare resources plus demographic information in the analysis allows for comparisons and conclusions as to which resources are most successful. Some of the limitations encountered in this study include possible human error as claims and other data used in the study was entered and handled by workers. Demographic information such as race, ethnicity, marital status etc. and also reasons for office visits were not available. Discharge instructions given by the doctor after an inpatient admission were not available and hence it would be hard to track if a medication was discontinued or the strength of the medication was reduced due to the doctor's orders or the patient's negligence. The current study may not have external validity or generalizability for asthma patients as the study sample was small and only consisted of patients from one insurance company in the state of Louisiana. The study assumed prescriptions filled as prescriptions consumed, which might not actually be the case.

In summary, these results suggest a pathway to reduce the burden to patients with asthma and to the healthcare system through increasing physician visits, which is associated with improved rescue medication adherence and therefore fewer emergency visits and inpatient admissions. Furthermore, the results provide evidence that certain populations; older, low income, and male; may benefit from additional education on monitoring and controlling asthma as these groups have higher levels of emergency visits and 30-day readmissions. These two preventive strategies are better for patient health, and they can reduce the use of costlier healthcare services in favor of less expensive physician visits and education programs. The strategies and analysis methods used here may be applied to the management of other chronic conditions with high utilization of emergency and hospital resources such as congestive heart failure or COPD.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

The study documented in this manuscript resulted from a research partnership among Louisiana State University and Louisiana Health Connections (LAHCA) and Centene Inc. In advance of this study the Institutional Review Board at Louisiana State University reviewed and approved the study. The data provided by LAHCA for this study was de-identified based on the LAHCA compliance policy and HIPPA guidelines for de-identification of data, particular for underage patients. This manuscript has not been published before to this submission. No financial support was received to conduct this study. The authors certify that we have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. All authors collaborated in this study and the manuscript, including study design, data gathering and analysis, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual contend and final approval.