To assess the additional value in the evaluation of incidents and adverse events by adding the IHI Skilled Nursing Facility Trigger Tool (SNFTT) to the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Global Trigger Tool (GTT) in an acute geriatric hospital.

Material and methodsA one-year retrospective study reviewing 240 electronic clinical records using the general GTT, either alone or combined with SNFTT. Main outcome measures: Number of triggers and identified adverse events (AEs), categories of severity and preventability of AEs, GTT incidence rates, and the number needed to alert (NNA).

ResultsOne hundred and thirty-seven AEs were identified in 107 patients (57.1 AEs per 100 admissions). Of these, 127 (92.7%) occurred 3 or more days after admissions; 49.6% of the harm events were preventable. The NNA for GTT plus SNFTT was 8.6. No significant difference was found using the general GTT alone versus the general GTT plus SNFTT in terms of the main outcome measures. Eleven categories of triggers were better identified when using GTT plus SNFTT because with GTT alone they were allocated to a category of “Other”: 9 from the care module (C15) and 2 from the medication module (M13).

ConclusionsThe study demonstrates that adding the SNFTT to the GTT did not increase its effectiveness as regards the evaluation of AEs. However, some triggers are better described in SNFTT and now have now been added into the general GTT method in our hospital.

Evaluar el valor añadido de la adición de la herramienta Skilled Nursing Facility Trigger Tool (SNFTT) a la herramienta Global Trigger Tool (GTT) del Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) en la evaluación de incidentes y episodios adversos en un hospital de cuidados agudos geriátricos.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de un año que revisó 240 historias clínicas electrónicas utilizando la herramienta GTT general, bien en solitario o combinada con SNFTT. Medidas del resultado principal: número de desencadenantes y episodios adversos (EA) identificados, categorías de gravedad y capacidad de prevención de EA, tasas de incidencia de GTT y número necesario para alertar (NNA).

ResultadosSe identificaron 137 EA en 107 pacientes (57,1 EA por cada 100 ingresos), de los cuales 127 (92,7%) se produjeron 3 o más días después del ingreso; el 49,6% de los episodios perjudiciales fueron prevenibles. El NNA para GTT más SNFTT fue 8,6. No se encontró diferencia significativa alguna al utilizar GTT general en solitario frente a GTT general más SNFTT en términos de medidas del resultado principal. Se identificaron de mejor manera 11 categorías de desencadenantes al utilizar GTT más SNFTT, dado que al utilizar GTT en solitario eran asignadas a la categoría de «Otros»: 9 desde el módulo de cuidados (C15) y 2 desde el módulo de medicación (M13).

ConclusionesEl estudio demuestra que la adición de la herramienta SNFTT a GTT no incrementó su efectividad en lo que concierne a la evaluación de los EA. Sin embargo, algunos desencadenantes son mejor descritos en SNFTT, que ha sido actualmente incorporado al método GTT general en nuestro hospital.

Adverse events (AEs) are defined as “unintended physical injuries resulting from medical care that require additional monitoring, treatment, or hospitalization, or that result in death”.1,2 AE due to hospital care errors remain common, despite extensive documentation of the risk to hospitalized individuals and efforts to improve in-hospital safety.1,3–5

One study evaluated the ability of different risk-monitoring systems to detect the incidence of AEs and found that the sensitivity of the IHI Global Trigger Tool (GTT) was 94.9% and its specificity 100%.6 The use of GTT resulted in detection and confirmation of 10 times as many serious AEs as the other methods tested. Nevertheless, in spite of improved monitoring, the rates of AEs that affect the safety of hospitalized individuals are still high.1,4

The GTT procedure was used for the first time in the Hospital Monte Naranco in 2007.7 The IHI Skilled Nursing Facility Trigger Tool for Measuring Adverse Events (SNFTT)8 provides an easy-to-use method for accurately identifying AEs (harm) and measuring their rate of incidence over time in skilled nursing facilities. It tool is based on the GTT methodology, that is, a retrospective review of a random sample of inpatient hospital records which uses “triggers” (or clues) to identify possible AEs. Our hospital is an acute geriatric hospital and the SNFTT has a variety of triggers and AEs that are typical in our geriatric patients.

The data on the general measurement properties of the GTT have been reported in a previous publication,6 to our knowledge no studies have to date evaluated, either the value of the SNFTT or the additional value of adding the SNFTT to the general GTT module, as have implemented in our hospital.

The aim of this study was to analyse the additional value of the SNFTT either when used alone or in combination with the GTT in our geriatric population which, in some cases, has the same AE risks as in Nursing Facilities.

Material and methodsSettingThis study was performed at Monte Naranco Hospital, Oviedo, Spain, an urban teaching hospital and acute geriatric hospital with 200 beds distributed across wards for cerebrovascular accidents, palliative care and, surgery as well as two acute geriatric care units. In the year of this study, the hospital had a total of 4452 individual admissions with aged>18 years, which accounted for 48,248 admission days.

Study design.A one-year retrospective study (2017) of the same electronic clinical records (Selene, Cerner, Kansas City, MO, USA) was conducted using the GTT2 alone or in conjuction with the SNFTT8 on the same inpatient clinical records to detect triggers (sentinel conditions believed to be linked to the occurrence of AEs) and AEs in 10 random samples every two weeks period (i.e. selecting every 10th patient in the admission list of the electronic clinical records) resulting in a total review of 240 clinical records. AEs were identified as externals when they were detected in the hospital but that had occurred in other hospitals or in long-term care homes. AEs that happened at home or in ambulatory care centers were not included.

Global Triger Tool analysisOne nurse (MD.M-F) and one doctor (F.V.) from the hospital, reviewed all records, applying the GTT toolkit as described in.2 From 4,452 eligible patient records, a total of 240 (5.4%) were selected for review following the GTT criteria. All selected records were included in the study. The team has more than 13 years of experience of reviewing patient records using the GTT. In a procedure that lasted no more than 20min, the nurse/doctor team reviewed all available information using the three modules (care, medication and surgical modules) of the GTT which are applicable to our hospital context where have no an intensive care unit, pediatric or gynecological patients. The SNFTT is designed to detect AEs (harm) and measure the rate of adverse event incidence over time in skilled nursing facilities, and has three modules: Care Module Triggers, Medication Module Triggers and Resident Care Module Triggers; this tool is based on the GTT methodology. Applying the SNFTT takes less than 25min.8

Adverse events (AE)All AE were assigned to one of a number of broad categories: infections, falls, medication errors, general care (pressure injuries, diaper dermatitis, skin tears, phlebitis and extravasation), surgery, diagnostic procedures, and discharges. The Barthel Index of activities of daily living was used to classify each patient's level of ability; scored from 0 to 10 in terms of each of the following 10 items: incontinent bowel and bladder, toilet use, feeding, dressing, and stairs; from 0 to 15 for: transfer and mobility; and from 0 to 5 for: grooming, and bathing. Overall scores of between 0 and 20 indicate extreme disability, while those between 80 and 100 indicate maximal independent activity.9

Categorization of severity of adverse eventsAEs and non-AE incidents were included in the review in accordance with the Index of the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) categories A–I.10

Preventable adverse eventsA Likert scale (with scores ranging from 1 for definitely not preventable to 4 for definitely preventable) was used (scores of 3 and 4 were considered to be preventable events).4 Cases where the individual reviewers allocated different scores to an event were discussed until, a consensus was reached. An AE was considered preventable if there were means available at the time to avoid it unless such means were not considered to be standard care.

Main outcome measuresTotal number of triggers detected, total number of AEs identified, distribution of identified AEs according to the NCC MERP categories of severity, Likert scale to evaluate the preventability of AEs, AEs per 100 admissions, AEs per 1000 admission days, and Percentage of admissions with at least one AE, and the NNA.

Statistical analysisAnonymized data are presented descriptively and were statistically analyzed the Student's t-test. Where appropriate p-values<0.05 were considered significant. Number needed to alert (NNA) was defined as the number of triggers needed to be reviewed to detect one AE.11

ResultsThe total length of stay of these 240 patients was 2,752 days. The majority of patients (80.8%) were patients over 75 years old: 29 patients<65 years (12.1%), 25 patients aged 65–75 years (10.4%), 18 aged 76–80 years (7.5%), 128 between 81 and 90 years (53.3%) and 40 patients were over 90 (16.7%). Barthel Index scores indicated that 36.7% of the patients had problems with activities of daily living (total or severe dependency): 65 patients (27.1%) scored≤20 (total dependency), 23 patients (9.6%), 25-35 (severe dependency), 36 patients (15%), 40–55 (moderate dependency), 72 patients (30%), 60–95 (mild), 19 patients (7.9%), 100 (independence), while scores were unrecorded for 25 patients (10.4%).

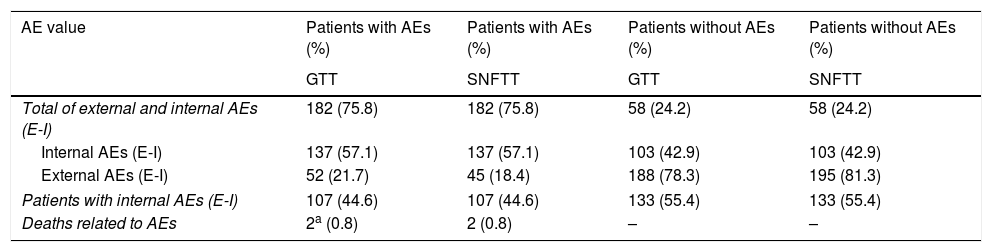

The results as GTT were the same both for the GTT alone approach and for the GTT plus SNFTT: AEs per 100 admissions 57.1, AEs per 1000 admission days 49.8 and the Percentage of admissions with at least one AE was 44.6. There was at least one AE identified in 44.6% of all admissions.

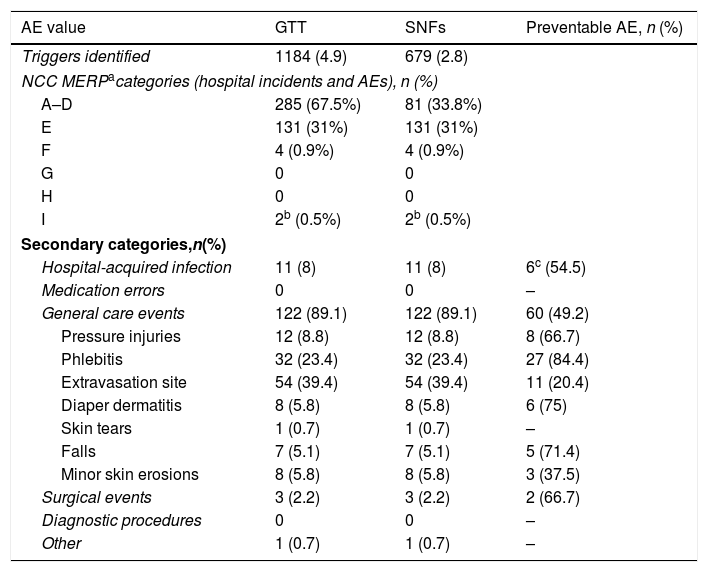

We found 1,184 triggers in the 240 patients (an average of 4.9 per patient), the total number of AE (i.e. both internal and external) was 182 (137 of which were internal), which were found in 107 patients. The distribution of the AEs identified in terms of the NCC MERP categories was 131 in category E (95.6%), 4 in category F (2.9%) and in category I (1.5%) (Tables 1 and 2). We further categorized the AEs into six groups (Table 2), and by far the majority of AEs were in the category general care events (89.1%) with extravasation site (39.4%) and phlebitis (23.4%) being the most frequent AEs, with health care associated infections being the group with the second most common (6 urinary tract infections, 4 lower respiratory tract infections and 1 oropharyngeal candidiasis infection). The analysis revealed that 68 of the 137 AEs identified using the trigger tool (49.6%) were preventable (Table 2). Of these, 127 (92.7%) occurred 3 or more days after admission. The NNA for GTT plus SNFTT was 8.6.

Characteristics of the population with and without adverse events (AEs) in the GTT and SNFTT (n=240 patients).

| AE value | Patients with AEs (%) | Patients with AEs (%) | Patients without AEs (%) | Patients without AEs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTT | SNFTT | GTT | SNFTT | |

| Total of external and internal AEs (E-I) | 182 (75.8) | 182 (75.8) | 58 (24.2) | 58 (24.2) |

| Internal AEs (E-I) | 137 (57.1) | 137 (57.1) | 103 (42.9) | 103 (42.9) |

| External AEs (E-I) | 52 (21.7) | 45 (18.4) | 188 (78.3) | 195 (81.3) |

| Patients with internal AEs (E-I) | 107 (44.6) | 107 (44.6) | 133 (55.4) | 133 (55.4) |

| Deaths related to AEs | 2a (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | – | – |

Adverse events (AEs; as defined by the Index of the National. Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERPa) identified in the 240 individuals analyzed using the Global Trigger Tool and Classification (secondary categories) as a function of their nature.

| AE value | GTT | SNFs | Preventable AE, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triggers identified | 1184 (4.9) | 679 (2.8) | |

| NCC MERPacategories (hospital incidents and AEs), n (%) | |||

| A–D | 285 (67.5%) | 81 (33.8%) | |

| E | 131 (31%) | 131 (31%) | |

| F | 4 (0.9%) | 4 (0.9%) | |

| G | 0 | 0 | |

| H | 0 | 0 | |

| I | 2b (0.5%) | 2b (0.5%) | |

| Secondary categories,n(%) | |||

| Hospital-acquired infection | 11 (8) | 11 (8) | 6c (54.5) |

| Medication errors | 0 | 0 | – |

| General care events | 122 (89.1) | 122 (89.1) | 60 (49.2) |

| Pressure injuries | 12 (8.8) | 12 (8.8) | 8 (66.7) |

| Phlebitis | 32 (23.4) | 32 (23.4) | 27 (84.4) |

| Extravasation site | 54 (39.4) | 54 (39.4) | 11 (20.4) |

| Diaper dermatitis | 8 (5.8) | 8 (5.8) | 6 (75) |

| Skin tears | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | – |

| Falls | 7 (5.1) | 7 (5.1) | 5 (71.4) |

| Minor skin erosions | 8 (5.8) | 8 (5.8) | 3 (37.5) |

| Surgical events | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (66.7) |

| Diagnostic procedures | 0 | 0 | – |

| Other | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | – |

A (circumstances or events occurred that had the capacity to cause an error), B (an error occurred but did not reach the patient), C (an error occurred that reached the patient but did not cause an AE), D (an error occurred that reached the patient and required monitoring to confirm that it resulted in no AE or required intervention to preclude an AE), E (an error occurred that may have contributed to or resulted in a temporary AE and which required intervention), F (an error occurred that may have contributed to or resulted in a temporary AE and required initial or prolonged hospitalization), G (an error occurred that may have contributed to or resulted in a permanent AE), H (an error occurred that required intervention necessary to sustain life), I (an error occurred that may have contributed to or resulted in death).

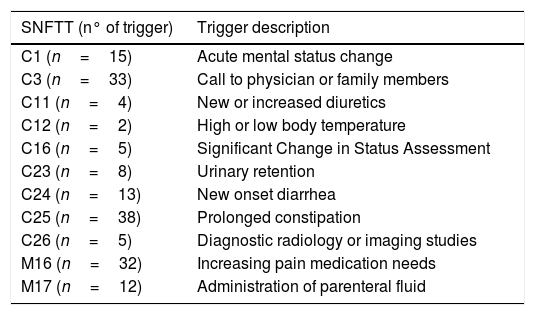

There was no difference in the number of AEs founded with the GTT alone and using the GTT with the SNFTT. However, the search for triggers was more effective in the SNFTT with respect the triggers C1, C3, C11, C12, C16, C23, C24, C25, C26 in the care module and M16 and M17 in the medication module (Table 3).

Triggers in SNFTT now included in our GTT.

| SNFTT (n° of trigger) | Trigger description |

|---|---|

| C1 (n=15) | Acute mental status change |

| C3 (n=33) | Call to physician or family members |

| C11 (n=4) | New or increased diuretics |

| C12 (n=2) | High or low body temperature |

| C16 (n=5) | Significant Change in Status Assessment |

| C23 (n=8) | Urinary retention |

| C24 (n=13) | New onset diarrhea |

| C25 (n=38) | Prolonged constipation |

| C26 (n=5) | Diagnostic radiology or imaging studies |

| M16 (n=32) | Increasing pain medication needs |

| M17 (n=12) | Administration of parenteral fluid |

To our knowledge, this study is the first report on the use of SNFTT in general, as is also the case in terms of evaluating the additional value of the SNFTT combined with the GTT when assessing levels of patient safety in a population of acute geriatric patients.

The general level of harm found in this study was higher than that previously reported using the GTT in our hospital: 24.5%, 29.4% and 23.3%, both respectively.7 There are a number of possible explanation for this: GTT was applied more effectively than in the previous study, although it is unlikely since staff carried out the reviews in both studies; record keeping may have improved in that the data needed for the analysis is recorded more effectively and/or consistently than in the past; the new incorporation of extravasation as a trigger; the patients admitted to the hospital now are generally older than in the past and are often very vulnerable patients with increased levels of polymedication and worse Barthel index scores; in 2017, a new ward was opened with new healthcare professionals working on it.

We found no significant difference regarding total number of AE or rates of AEs per 100 admissions or per 1000 admission days, suggesting no additional value was added by using the SNFTT with respect to the level of harm identified. We found the highest number of AEs in the temporary harm categories E and F, which is consistent with general findings from other works measuring AEs using the GTT.4,11–14 We found two category I events (causing or contributing to patient death), one aspiration and one surgical event (fluid overload) in old patients with other underlying diseases.

When evaluating the additional value of the SNFTT with regard to the severity of the AEs identified, we found no significant difference between using GTT and the GTT alone and GTT plus SNFTT.

The AEs identifies were allocated to the same categories using the GTT alone and the GTT plus the SNFTT, although some triggers were easier to search for the electronic clinical records with the SNFTT because, it provides more accurate description to discern certain triggers which in the GTT are subsumed in the category “Other” in both the care module and medication care module. This might suggest that the SNFTT may sometimes identify specific triggers but not any new AEs. The most commonly identified AEs were general care events, which are frequent in such geriatric patients, and the second most commonly identified AEs were infections, also common in this demographic. The low occurrence of medication AEs, not detected in these patients and which is a typical shortcoming of this tool, is in line with our findings in our earlier work.7

One limitations of the study that it is retrospective and includes only a one hospital; and the results may, therefore, not be transferable to other acute geriatric hospitals. Our study was carried out by a single team but interrater reliability between team members was not tested, and this may have impacted to some degree the results.

In conclusion, the SNFTT is a new Trigger Tool which is easy to use and only requires 25min with each electronic clinical record. Our study showed there to be no additional value to using this tool as regards the general safety level measured in AEs per 100 admissions and in AEs per 1000 admission days. Neither were there any significant difference in the overall distribution of the AEs identified across the five NCC MERP harm categories using SNFTT versus in addition to GTT compared to using GTT alone. However, some triggers in the SNFTT were better tailored to our geriatric population than those of the GTT and consequently these, we have now been included in our general GTT triggers.

Authors’ contributionsData of patients, MD.M-F, B.C., B. Cu. and F. V.; supervised of the data, MD.M-F and F.V.; methodology, MD.M-F, J.A. and F.V.; writing—original draft, review and editing preparation, MD.M-F, J. A. and F.V.; funding acquisition, MD.M-F. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThe study was funded by the Sociedad Española de Calidad Asistencial (SECA)/Fundación Española de Calidad Asistencial (FECA) Grant (SECA Grant 2017).

Conflicts of interestNone.