Edited by: Dr. Sergi Bermúdez i Badia

(University of Madeira, Funchal, , Portugal)

Dr. Alice Chirico

(No Organisation - Home based - 0595549)

Dr. Andrea Gaggioli

(Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milano,Italy)

Prof. Dr. Ana Lúcia Faria

(University of Madeira, Funchal, Portugal)

Last update: December 2025

More infoSmooth pursuit training (SPT) is recognized as an effective intervention for spatial neglect by guiding patients’ attention toward the contralesional hemifield through repetitive tracking of moving visual stimuli. However, traditional SPT approaches lack standardized, real-time feedback on gaze and head position and patient motivation, limiting therapists' ability to monitor attention and patients' engagement effectively. Combining immersive virtual reality (VR) with eye tracking may overcome these limitations by providing immediate automated feedback, enhancing therapeutic outcomes and being associated with increased awareness of deficits.

MethodsWe developed and evaluated an immersive Virtual Reality Eye Movement Training (VR-EMT) paradigm integrating eye tracking and real-time automated feedback on gaze and head orientation. Twelve chronic post-stroke patients with left-sided neglect completed 10 VR-EMT sessions (each lasting 18 min). We assessed performance in a spatially lateralized object transport task, head rotation behavior, gaze distribution, usability, and patient preferences in comparison to traditional SPT.

ResultsVR-EMT was independently executable and highly accepted by patients. Real-time feedback improved patients' head orientation awareness and adjustments. Task accuracy decreased with increasing task difficulty, indicating effective demand modulation. A persistent ipsilesional gaze bias was found during breaks. Patients preferred VR-EMT over traditional SPT due to enhanced feedback, motivation, and challenge. Cybersickness was minimal and did not impair performance.

ConclusionsThis feasibility study demonstrated that VR-EMT integrating eye tracking and immediate feedback is technically feasible, clinically applicable, well-accepted, and subjectively preferred over traditional methods in chronic post-stroke neglect patients. Eye tracking functioned reliably, even as the sole interaction modality. Real-time feedback facilitated rapid behavioral adjustments, highlighting the potential for individualized interventions and remote application. Future studies should evaluate clinical efficacy and the benefits of eye-tracking-based attentional assessment.

Stroke is the second leading cause of mortality worldwide and a major contributor to chronic disabilities in adults (Wafa et al., 2020). Given the significant burden that cardiovascular disease places on current and future healthcare systems worldwide, there is an urgent need for affordable, accessible, clinically derived, and validated rehabilitation tools tailored to the specific needs of stroke survivors.

Spatial neglect, a prevalent and disabling consequence of stroke, is characterized by the failure to attend to or interact with stimuli in the contralesional hemifield (Heilman et al., 2000; Karnath & Rorden, 2012). This neuropsychological condition significantly impairs independent daily functioning (Jehkonen et al., 2000, 2006) and is associated with a lateral attention bias toward the ipsilesional side, as evidenced by deviations of gaze and head position along the horizontal plane (Corbetta & Shulman, 2011; Karnath, 2015). In the acute post-stroke phase, patients predominantly orient their head and gaze ipsilesionally. Although the syndrome becomes less overt in chronic phases (Bartolomeo, 2021; Bonato, 2012), deficits in visual exploration persist even in recovered patients (Knoppe et al., 2022). These include an attentional bias toward ipsilesional stimuli (Karnath, 1998; Ohmatsu et al., 2019), re-fixations and perseverations, particularly on the ipsilesional side (Paladini et al., 2019; Schindler et al., 2006), asymmetrical scanning patterns (Cox & Aimola Davies, 2020; Müri et al., 2009), and prolonged fixation on ipsilesional stimuli (Behrmann et al., 1997). Compensatory strategies, such as contralesional cross-over of increased head turns, are often observed, particularly in chronic phases of recovery (Gall et al., 2012; Takamura et al., 2016). Although the reported prevalence of stroke-related neglect varies widely, depending on lesion site and diagnostic tests applied (Esposito et al., 2021), it averages around 30 % across all stroke patients. Thus, there is a high need for effective, evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation programs.

Neglect rehabilitationTop-down and bottom-up approaches are widely applied for neglect rehabilitation. Top-down approaches depend on patients' awareness of deficits and require active engagement during training. These techniques require patients to voluntarily direct their attention to the neglected side using targeted cues and therapist feedback, often in tasks with copying, reading, and visual scanning that demand active exploration and visual search. In contrast, bottom-up approaches do not require awareness or active participation, using external stimulation methods, such as neck muscle vibration, caloric nystagmus, smooth pursuit training (SPT), and optokinetic stimulation therapy (OKS) to shift attention to the neglected side (Conti & Arnone, 2016; Dintén-Fernández et al., 2019). Combining top-down and bottom-up approaches has proven effective in reducing neglect-specific behaviors (Bode et al., 2023; Machner et al., 2014; Schröder et al., 2008).

Currently, there is no established gold standard for neglect rehabilitation. The effectiveness of various rehabilitation methods remains inconclusive due to methodological limitations (Bowen et al., 2013). However, some approaches show promising outcomes. For instance, the German Neurological Society guidelines recommend active exploration, contralesional orientation, and smooth pursuit training (SPT), in which patients are instructed to follow slowly moving stimuli toward the contralesional side with their eyes to promote attentional shifts and reduce neglect symptoms (Karnath & Schenk, 2003). Repetitive OKS combined with SPT has been described as an effective method for neglect rehabilitation, particularly in the chronic phase (Cavedoni et al., 2022; Kerkhoff et al., 2006, 2012; Liu et al., 2019). The task involves tracking leftward moving stimuli, such as dots or symbols, across a screen to promote leftward attention. Patients with left neglect fixate on a stimulus on the right, track it contralesionally, and hold fixation for three seconds before shifting to the next target on the right side. Therapists ensure patients maintain a central head position and follow stimuli correctly with their gaze during 10–15 min SPT sessions, typically conducted 2–3 times per week. Importantly, explicit instructions for smooth pursuit movements were more effective than unguided approaches. Leftward-moving SPT reduces neglect symptoms, while rightward-moving SPT may worsen them (Chen et al., 2015; Kerkhoff et al., 1999; von der Gablentz et al., 2019). SPT effectively activates visual as well as vestibular pathways, aiding in improving spatial attention and perception by modulating brain areas involved in spatial coding and attention networks, thereby improving neglect symptoms (Doricchi et al., 2002; von der Gablentz et al., 2019). This was evidenced by head-turning responses toward leftward stimuli (Pizzamiglio et al., 1990).

A related approach is OKS, which involves rapid contralesional stimulus motion and induces optokinetic nystagmus. In contrast to SPT, OKS does not require foveal fixation; eye movements are reactive rather than volitional, and vestibular networks are more strongly engaged (Dieterich et al., 1998; Gaymard & Pierrot-Deseiliigny, 1999; Kerkhoff et al., 2012). SPT and OKS are sometimes used interchangeably (Kaiser et al., 2022), possibly because even slow-moving OKS stimuli have been shown to induce training effects (Keller et al., 2003). However, direct comparisons of both two approaches, examining the effects of stimulation speed, the role of volitional and reactive eye movements, and their effects on brain networks are currently lacking. SPT, alone or in combination with exploration training, sustains performance improvements in neglect tests and enhances daily task performance. Furthermore, neck muscle vibration and continuous theta burst stimulation were also recommended by the German clinical guidelines on neglect rehabilitation, especially with complementary training (Karnath et al., 2023).

Limitations of traditional SPTRegarding SPT, its full potential is hindered by the absence of immediate, precise feedback, standardized, personalized treatment protocols, as different neglect subtypes benefit from tailored therapeutic approaches (Spaccavento et al., 2017), and progress monitoring. The reliance on therapist supervision, including monitoring head positioning and maintaining attention, renders them labor-intensive (Tavaszi et al., 2021). Therapists further have no direct insight into patients’ perceptual and attentional experience during training. Additionally, the inability to control distractors and track which stimuli the patient is actively following, compromises focus and effectiveness (Ogourtsova et al., 2017). On one hand, leftward-moving visual stimuli increase left-sided attention, underscoring their importance as a rehabilitation strategy to automatically guide patients’ attention to the left (Plummer et al., 2006). On the other hand, overcompensation presents another challenge. For example, leftward-moving stimuli can create an illusion of rightward rotation, prompting patients to turn their head or body leftward, reducing therapeutic benefits (Pérez-Robledo et al., 2023). Finally, current training approaches insufficiently address the severity of neglect and co-occurring deficits, such as motor or additional perceptual deficits, which profoundly affect the effectiveness of rehabilitation strategies. These limitations highlight the need for dynamic, feedback-driven, ecologically valid, and automated patient-centered methods that provide precise, immediate feedback. Addressing these limitations could enhance patient engagement and the overall effectiveness of SPT in clinical practice.

Immersive virtual realityApplications using Virtual (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) have shown efficacy in diagnosing and rehabilitating neglect (Belger et al., 2024; Ogourtsova et al., 2017; Stammler et al., 2023). VR tools, in particular, enable precise head and eye movement tracking and objective behavioral measurements in controlled, ecologically valid, and distraction-minimized environments. This improves patients’ ability to focus on training tasks, while real-time feedback and independent task execution support continuous progress monitoring. Studies have demonstrated that VR-based interventions can outperform traditional training methods (Bourgeois et al., 2023; Cavedoni et al., 2022; Faria et al., 2016). By integrating real-world relevance, gamification, and adaptable interaction, VR enhances patient motivation, engagement, and training frequency, positioning it as a particularly promising tool for advancing training methodologies in neglect rehabilitation.

Neglect rehabilitation using VRVR is increasingly utilized in neglect rehabilitation, proving effective in improving patient engagement and rehabilitation outcomes (Laver et al., 2017; Ogourtsova et al., 2017; Pedroli et al., 2015). For instance, Kim et al. (2015) investigated the effectiveness of HMDs in delivering SPT. They compared performance in line-bisection tasks under four conditions: static and leftward-moving stripes on either a computer screen or an HMD. The results showed that leftward-moving stripes on the HMD were most effective in inducing a leftward bias, highlighting the potential of HMDs for controlled delivery of SPT. However, its repetitive nature may limit patient motivation in clinical practice. To address this issue, VR-based interventions have been proposed as a means of sustaining patient attention and encouraging active participation. Choi et al. (2021) showed that neglect patients receiving VR interventions performed significantly better on neglect tests post-intervention compared to a control group receiving traditional neglect training. In the VR task and visual exploration tasks, they also exhibited increased horizontal head rotation, both in terms of amplitude and velocity. Similarly, Pérez-Robledo et al. (2023) proposed a randomized double-blind trial for chronic left neglect patients with right-hemispheric lesions, using a 10-week protocol of short VR-based sessions featuring leftward-moving SPT stimuli.

Combining VR and eye tracking has high potential for neglect assessment and rehabilitation (Hougaard et al., 2021; Kaiser et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2004; Yasuda et al., 2020). Studies demonstrate that VR-ET systems enable neglect patients to interact with virtual objects via gaze fixation, regardless of neglect severity, providing precise behavioral insights beyond traditional methods (Knoppe et al., 2022; Uimonen et al., 2024). In addition, affordable HMDs with integrated eye tracking enhance accessibility, while the sensitivity of eye tracking makes it a superior tool for measuring and treating neglect (Cox & Aimola Davies, 2020).

Study objectivesWe developed and evaluated an immersive VR training task combining the clinical advantages of this technology with evidence-based neglect therapeutic components to overcome current limitations. This proof-of-concept study combines gamification principles with SPT, visual exploration, and real-world distractors featuring everyday scenarios, while providing real-time feedback for eye and head movements. There were three objectives in this study:

- (1)

Feedback and performance evaluation: We adapted traditional SPT to VR, providing immediate visual and auditory feedback on eye and head deviations. We examined whether real-time feedback improves patients’ focus on task performance and facilitates independent task execution. Additionally, we evaluated how task difficulty influenced patient performance, including task accuracy, head rotation behavior in response to automatic feedback, and optional program assistance. We aimed to determine if difficulty levels were appropriately scaled and how neglect-specific behaviors changed with increasing complexity, hypothesizing that higher difficulty would reduce performance.

- (2)

Usability and feasibility: We assessed the usability, feasibility, acceptability, and engagement of the VR-based neglect training, including comparisons to traditional approaches.

- (3)

Immediate effects on exploration and task performance: We investigated immediate behavioral effects of the VR-based training on spontaneous visual exploration toward the contralesional side and resting behavior during break phases. Additionally, we analyzed short-term changes in task performance and head rotation behavior within the first training session and evaluated participants’ subjective ratings on short-term performance gains, heightened deficit awareness, and perceived therapeutic benefit.

N = 14 chronic (i.e., more than 6 months) post-stroke patients with left-sided neglect participated, of which n = 12 completed the entire training (n = 1 early discharge from the clinic, n = 1 scheduling conflicts with concurrent therapy sessions). Participants were recruited from the Clinic for Cognitive Neurology, an outpatient clinic for neurological patients. The study took part, while they were enrolled in their regular treatment program at the clinic. Inclusion required the presence of left-sided spatial neglect due to right-hemispheric stroke, confirmed through recent medical reports, neglect screenings, and evaluations conducted by neuropsychologists and orthoptists. Mild or discrete neglect was defined by pathological performance in at least one standardized neglect test, a documented clinical diagnosis of neglect in the most recent medical report, and reported lateralized deficits in everyday life. Participants were aged 18 to 80, demonstrated adequate comprehension and communication skills, and provided informed consent. Participants were excluded if they had a history of seizures within the past two years, substance abuse, acute psychosis, dizziness, aphasia, or were pregnant.

Data collectionData collection comprised three key components (1) clinical evaluations using neuropsychological tests and the iVRoad task for neglect evaluation (Belger et al., 2023, 2024), (2) questionnaires assessing user experience and usability, and (3) behavioral recordings from the VR rehabilitation program.

(1) Neuropsychological test battery

Neglect assessment involved multiple conventional paper-and-pencil tests, taking into account the limited sensitivity of conventional assessments and the strongly varying reported occurrence of post-stroke neglect (Azouvi, 2017; Esposito et al., 2021). As part of routine clinical evaluations, participants completed the Sensitive Neglect Test (SNT; Reinhart et al., 2016) in both single-task and dual-task, as well as subtests from the Neglect Test Battery (NET; Leplow, 1999), which is the German adaptation of the Behavioural Inattention Test (Wilson et al., 1987). The tests were administered and scored according to standardized procedures outlined in their respective manuals. Not all patients completed the full test battery, as testing was discontinued once neglect was clearly detected, in accordance with standard clinical procedures aimed at reducing patient burden. In addition, all patients completed the iVRoad assessment, and the results were analyzed using the machine learning approach from Belger et al. (2023) to obtain predicted probabilities for neglect classification.

(2) Questionnaires

CSQ-VR. We administered the Cybersickness in Virtual Reality Questionnaire (CSQ-VR; Kourtesis et al., 2023) immediately before and after the first VR training session to evaluate any cybersickness-related symptoms before and after the first VR session. This questionnaire is a shortened cybersickness questionnaire that measures the three subfactors nausea, vestibular symptoms, and oculomotor symptoms.

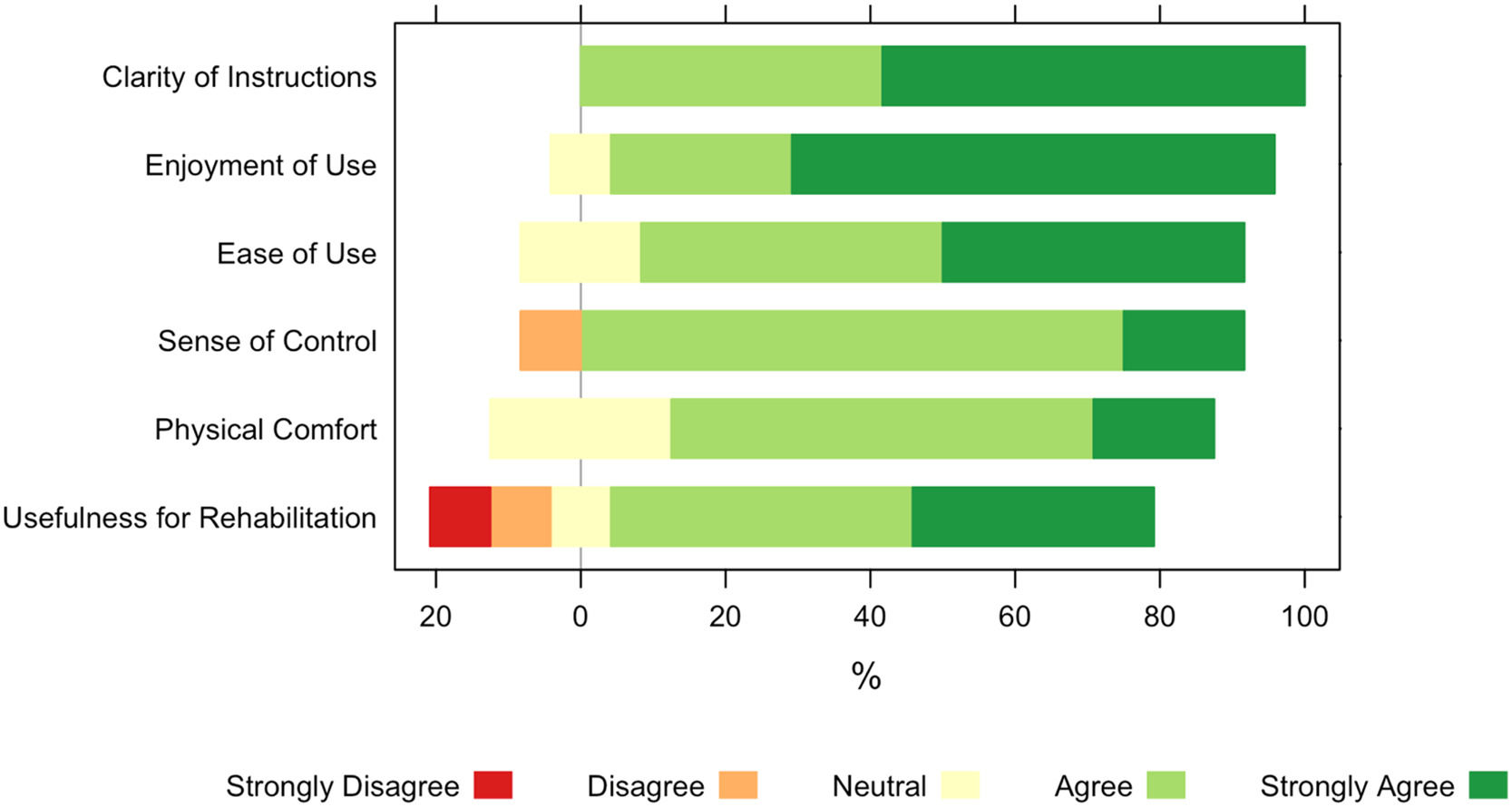

USEQ. Following the final VR training session, we used the User Satisfaction Evaluation Questionnaire (USEQ; Gil-Gómez et al., 2017) to measure satisfaction with the VR training. Since all patients were familiar with traditional SPT—which they received three times per week as part of their standard clinical care—we employed custom questionnaires. It was applied to evaluate the usability and user experience including comfort, engagement, and the perceived effectiveness of the VR training. Participants rated six questions on a 5-point Likert scale, from 'strongly disagree' (1) to 'strongly agree' (5). With five positive and one negative item, scores range from 6 (poor usability) to 30 (excellent usability).

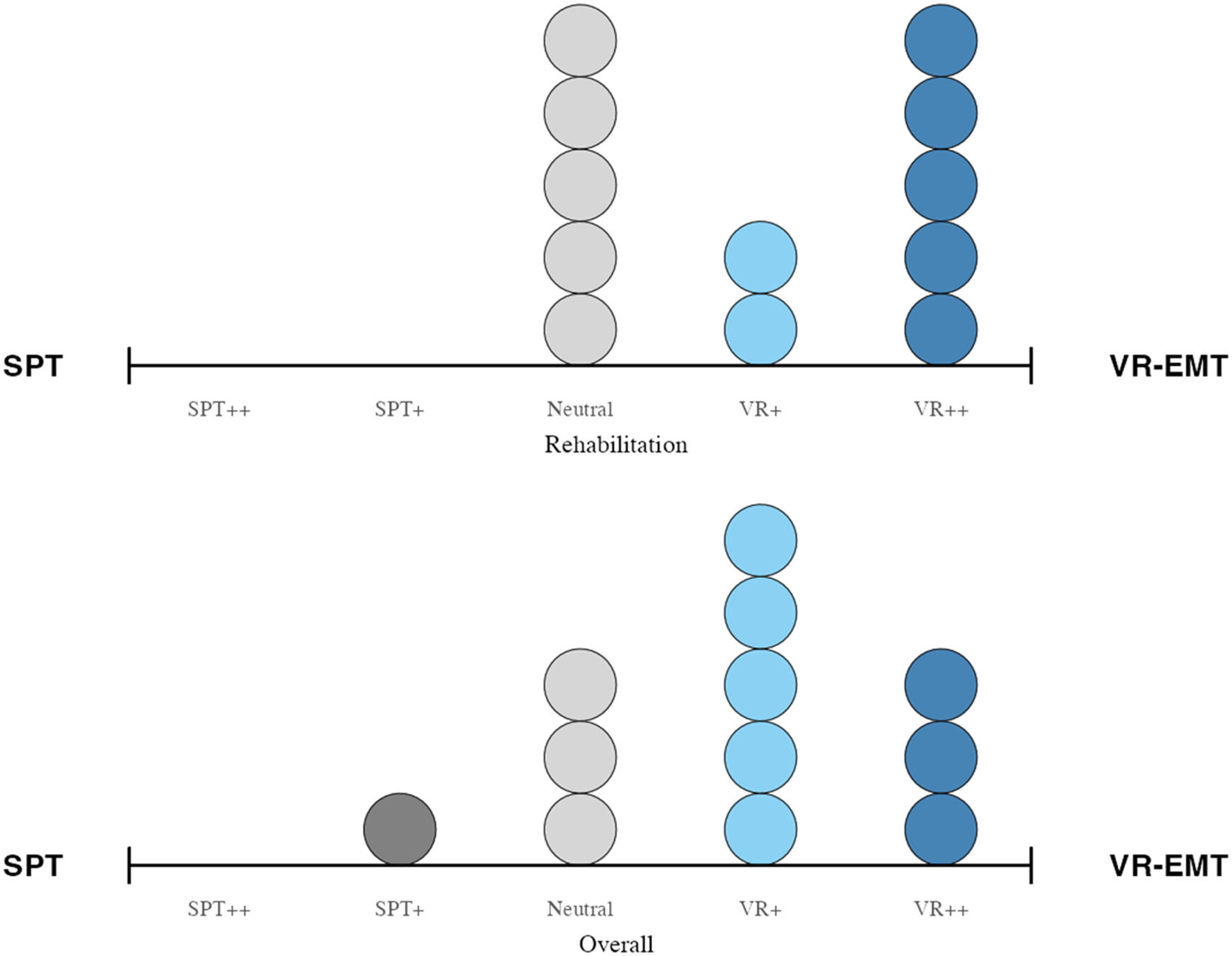

Comparison of VR with traditional SPT. Participants were asked to compare their experiences with both VR-EMT and traditional SPT to assess user experience and likability. A seven-item questionnaire was administered, where participants indicated their preferences on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strong preference for traditional SPT), through 3 (no preference), to 5 (strong preference for VR training). The items evaluated feedback on general system functionality, clarity of instructions, preference for type of training, training effect of feedback on head rotations, preference for home use, perceived usefulness for the own rehabilitation, and an overall preference score.

(3) Virtual Reality Eye Movement Training (VR-EMT)

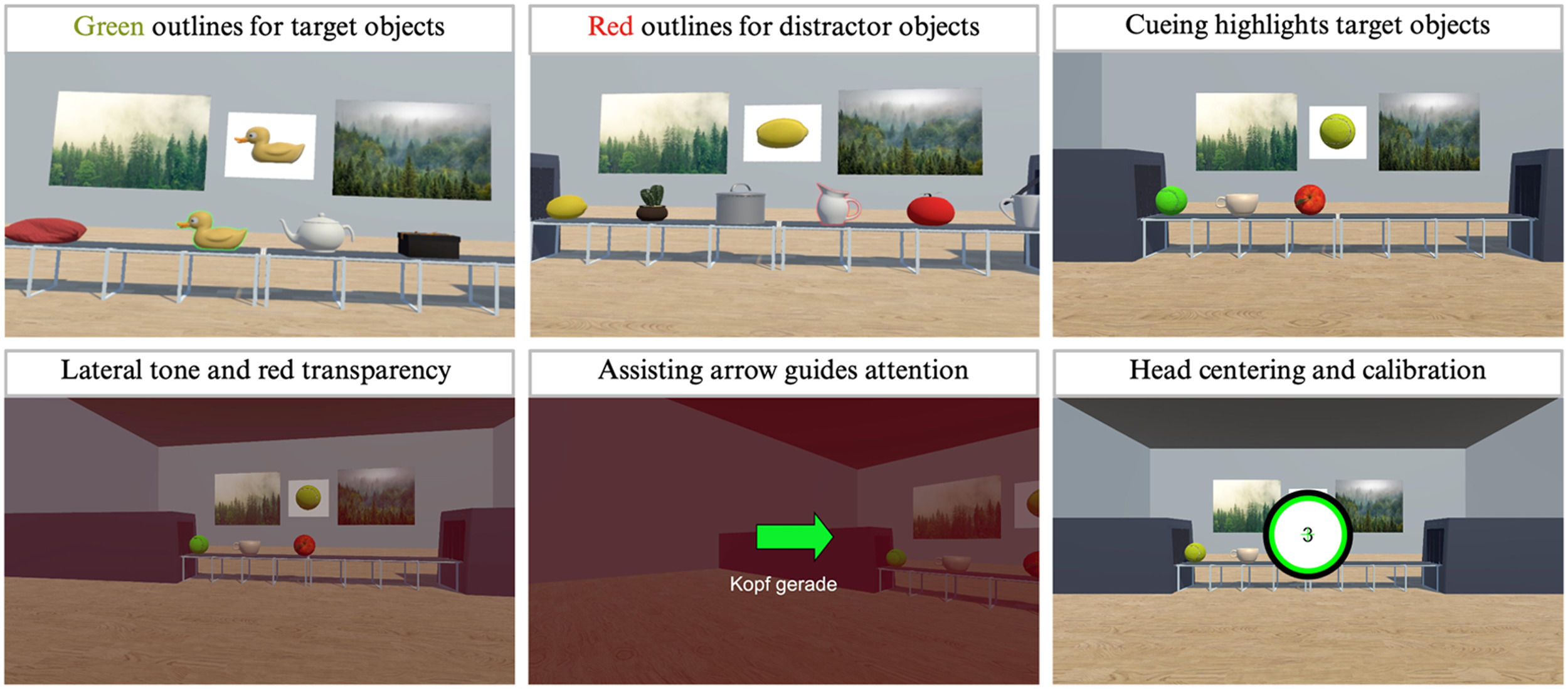

Elements of conventional SPT were integrated into an immersive VR training protocol for neglect rehabilitation (Fig. 1). In the VR-EMT, participants visually tracked objects moving leftward on a conveyor belt. Once the target object reached the left side, the belt stopped. Participants then had to fixate that object for three seconds in total before shifting their gaze to a new target object on the right side (requiring a saccade to the right) to repeat the process. All target objects were within their visual field, not requiring any head movements.

Virtual environment and phases of the VR neglect training (A–D). The VR neglect training integrates both patient and therapist perspectives. While patients engage in the task wearing VR glasses, therapists monitor gaze activity in real time on a computer screen. (A) Introduction and tutorial phase: Patients confirm a target circle on the left using gaze-based input. Cueing elements (e.g., blinking prompts and arrows) assist the process if patients fail to find the button. (B) Active training phase: Objects must be tracked from right to left and fixated on the left side for 3 s. The position and identity of target objects vary by level. Each level consists of three 5-min transport scenes. (C) Break phase: A 1-min session break features leftward-moving stimuli. Participants can freely explore the virtual environment. (D) Feedback phase: At the end of each session, results are presented and performance can be discussed with the therapist.

This novel VR system features full eye tracking as the sole interaction method for the training task and real-time automated feedback to guide patients’ attention during neglect training. That is, participants interacted with the virtual environment exclusively by using the integrated eye-tracking system, which was calibrated and tested before each session. In addition, they received feedback on their gaze and head orientation while supporting adaptive engagement during the training scenario. Participants were instructed to keep their heads neutral while following leftward-moving virtual objects on a belt with their gaze (1 m/s).

The VR training consisted of 10 sessions across five levels, with each level conducted twice. Tutorials were provided before levels 1, 3, and 5 to familiarize participants with the training environment, instructions including system feedback, interaction with the eye-tracking system, immediate online feedback on their behavior, and any level-specific requirements (e.g., additional belts, different target objects). The training was completed over a period of 2–5 weeks, depending on individual scheduling within the clinical routine. Most participants completed one level per session, and took part in the training two to three times per week. In rare cases (5 % of sessions), two sessions were conducted on the same day due to organizational constraints. Each level comprised three 5 min training intervals, each followed by a 1 min break (i.e., 15 min training, 3 min break in total per session; 180 min training over 10 sessions). At the end of each session, participants received feedback on their performance, including the total number of objects successfully transported to the left, head rotation feedback with total duration for each side and assistance needed from the program with total duration for each side.

Interaction and immediate feedback. The system provided various immediate behavioral feedback on head and eye deviations to enhance participant engagement and task performance. To increase leftward attention, interaction buttons were placed on the left side of the visual field; participants had to gaze at these buttons for three seconds to proceed with the task. Importantly, participants interacted solely using the integrated eye tracking in the VR system, without requiring additional controllers.

We implemented multiple cueing mechanisms to support neglect patients in completing the training most intuitively. This included target objects outlined in green and non-target objects in red upon viewing, giving immediate feedback. If participants failed to look at any target object for 10 s, the task automatically paused, and the target object blinked green to redirect attention. Cueing was further activated if a target object remained unattended at the very left, which was the final position on the belt (Fig. 2).

In addition, if the head deviated more than 10° to the left or right, the virtual background became semi-transparent red, accompanied by a lateralized auditory cue (e.g., a tone from the left side for leftward deviating head movement). This overlay indicated the deviation while keeping the environment partly visible. This feedback ceased immediately once the head returned to the central position. However, if this feedback persisted for more than 10 s, the task automatically paused, and system assistance was activated: a green arrow guided the user's head back to the neutral position, where a central dot appeared. To resume the task, the participant needed to align their gaze to a cross, representing their head midline, with the central dot for three seconds. This provided them with immediate objective feedback that their head position was centered again.

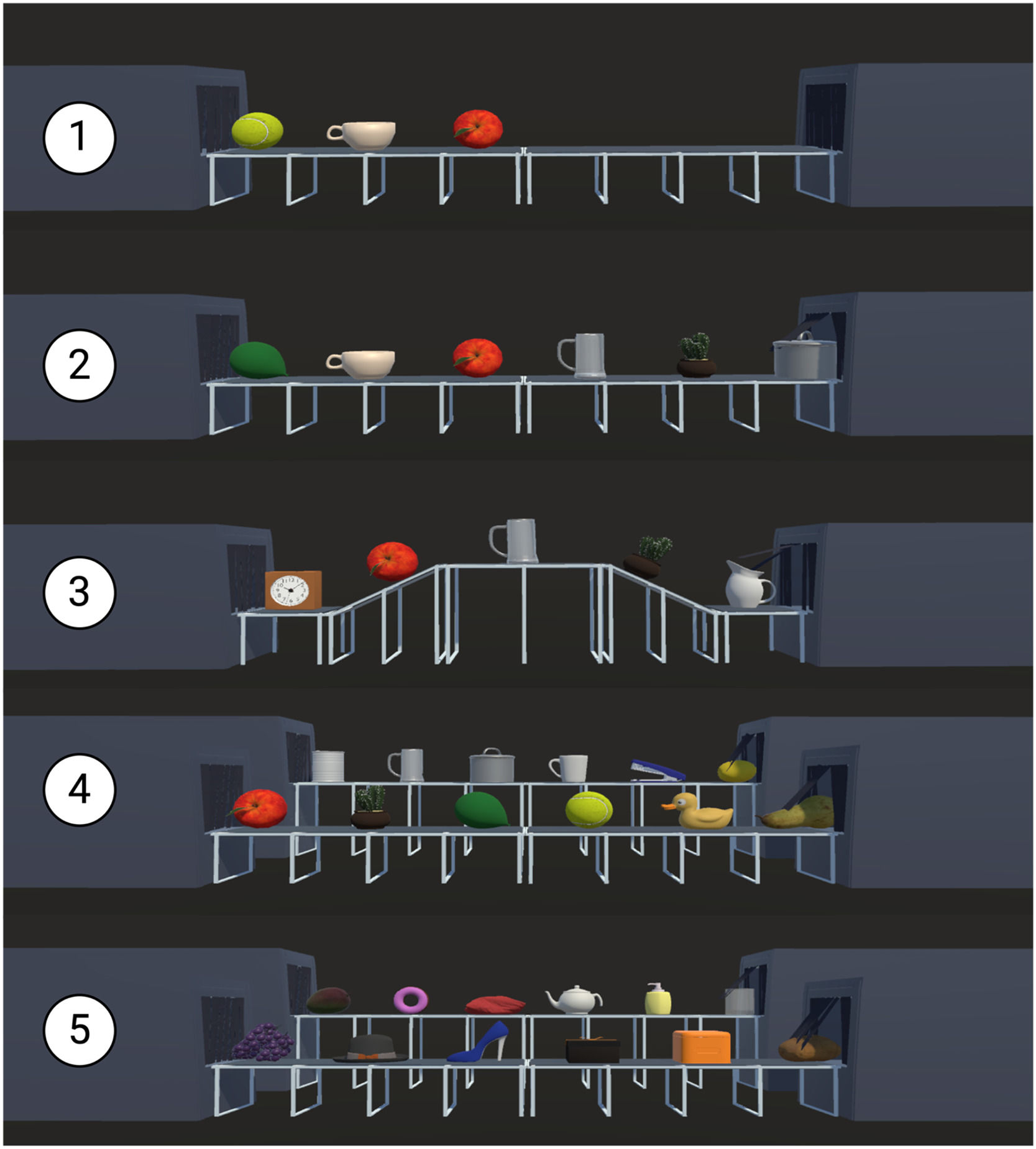

Training levels and target objects. All participants completed five consecutive training levels, each repeated twice before progressing to the next level. In each level, participants tracked a single object moving on a conveyor belt from right to left, with a white poster in the background indicating the current target object. To sustain attention, a different target object was presented during each transport, while the number of distractor objects increased with each level. Target objects and conveyor belt sequences were standardized across all participants to ensure repeatability. Fig. 3 illustrates the levels and their respective characteristics. To enhance familiarity and recognizability, we used validated and standardized 3D everyday objects from Tromp et al. (2020). These open-access virtual objects, tested for visual complexity and object recognition, contributed to the ecological validity of the VR environment.

Overview of training levels featuring one (levels 1–3) or two conveyor belts (levels 4–5) with objects moving leftward, varying target objects, and increasing number of distractor objects.

Note. Level 1 required participants to follow one target object at a time, positioned at the front of a straight conveyor belt, accompanied by two distractor objects. In level 2, the number of distractors increased to five. Level 3 introduced a horizontally curved conveyor belt with continuously appearing distractor objects. Level 4 added a second, parallel belt displaying simultaneous object streams. In level 5, participants were required to actively search for the target object across both belts. Only one target object was presented at a time, and levels ran for a fixed duration rather than ending after a set number of trials.

Breaks. After each 5 min training block, a 1 min break or relaxation phase in VR was provided. Participants were immersed in a virtual balcony environment featuring various objects, such as bubbles, balloons, or balls, slowly drifting from right to left at a constant speed of 1.6 m/s, thereby providing passive SPT. The breaks served as a pause from the active training task and were designed to maintain SPT while allowing participants to explore the virtual environment at their own pace, without receiving any performance-related feedback. The relaxing atmosphere was enhanced by naturalistic background sounds, including birds singing. No specific instructions were given during this phase, and participants were encouraged to explore the environment freely. However, these scenarios had two additional effects: they provided further leftward stimulation and allowed for the examination of neglect-typical biases during uninstructed free exploration.

Therapists’ insights into patient behavior. Therapists monitored participants' views and system feedback in real time via a desktop screen, gaining immediate insights into patient behavior. A red fixation cross displayed participants' gaze positions, enabling real-time visualization of their visual attention. The VR task operated autonomously, requiring therapists only to initiate the program, start calibration of the eye-tracking system and later review system-generated results with patients, with no need for intervention during training. If required, however, the task could be paused at all times.

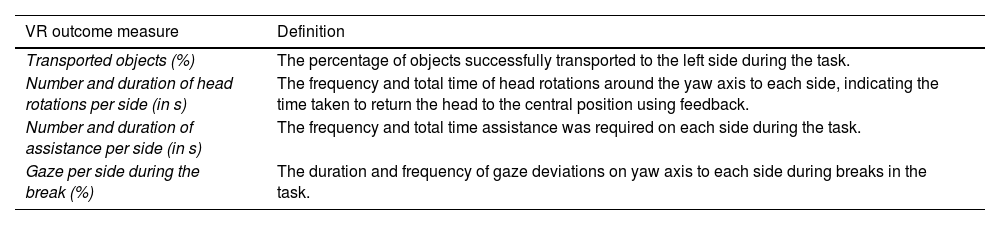

Outcome measures. Eye, head, and event data were logged at all times in VR (see Table 1 for an overview of the outcome measures that were calculated).

Outcome measures of the VR-EMT.

The VR task was conducted in a 4 × 4-meter room with a swivel chair positioned at the center. We utilized the HTC Vive Pro Eye HMD, which features an integrated eye-tracking system operating at up to 120 Hz, a horizontal field of view of 110 degrees, and a resolution of 1440 × 1600 pixels per eye. The HMD was connected to a portable workstation equipped with an Intel i7–9700 processor, 16 GB of RAM, and an Nvidia GeForce RTX 2070 graphics card. All interactions within the virtual environment—including following instructions, submitting answers, and tracking objects—were performed entirely using the integrated eye-tracking system and head movements within the HMD. The eye-tracking system was calibrated before each training session using the manufacturer's built-in calibration program by Tobii. The VR-EMT program was developed using the Unity development platform (version 2020.3.37f1) with the C# programming language.

Statistical analysesAll analyses were conducted using R (version 1.79; R Core Team, 2022) and RStudio (version 4.2.1; RStudio Team, 2020), with data preprocessing and manipulation performed via the tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019). Statistical procedures utilized the emmeans (Lenth, 2017) and lmerTest packages (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) and jtools (Long, 2017) supported model visualization and interpretation. The here (Müller, 2017) package facilitated reproducible file management, and flextable (Gohel & Skintzos, 2017) was used to create publication-ready tables. Descriptive statistics and psychometric analyses were conducted using psych (Revelle, 2007), with the easystats (Lüdecke et al., 2022) family streamlining workflows and diagnostics. Descriptive statistics for the study population were reported, and statistical significance was set at p < .05. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s HSD with 95 % confidence intervals and effect sizes. Missing VR data (3.61 %; 13 trials) were imputed by a hot deck method (Andrige & Little, 2010). Linear-mixed effects models (LMM) were employed and incorporated a random intercept for participant to account for inter-individual variability.

For the feedback and performance evaluation, a LMM was employed to predict the percentage of accurately transported objects. For usability and feasibility, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the results. Additionally, an LMM was applied to examine the effects of the three factors derived from the CSQ-VR, the two time points (pre- and post-intervention), and their interactions on the outcome score. Regarding performance evaluation, descriptive statistics were first computed for key performance metrics, including the number of correctly transported objects, head deviations, and instances of program assistance. To evaluate immediate effects on exploration and task behavior, LMMs were employed. For the head rotation counts, the fixed effects included task difficulty level, transport part, and side. Immediate effects, such as changes in visual exploration of the left and right sides, were assessed across session breaks to capture within-training changes.

During break scenes, participants were free to explore the virtual environment without any tasks or feedback. Data were excluded if both eyes were closed, and only horizontal gaze data were analyzed when the eyes remained open for at least 10 s. For exploratory analyses, data from the first performance of each level (1 to 5) were included. Gaze angles between −180° to −5° and 5° to 180° were analyzed; angles within the range of −5° to 5° were considered central and excluded from categorization.

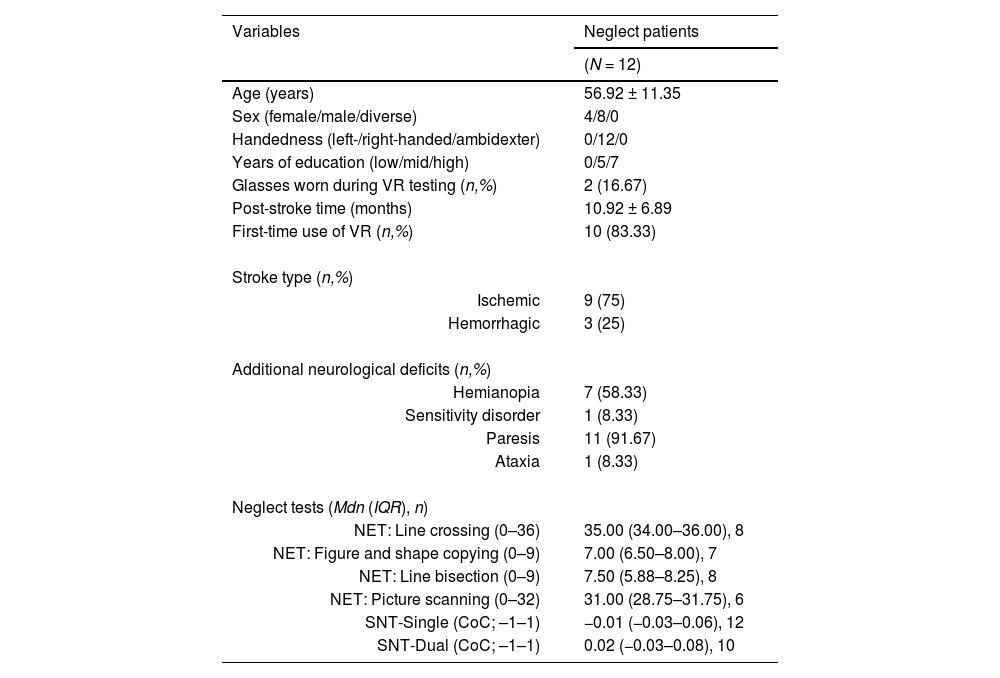

ResultsTable 2 provides a summary of the participants’ demographic data. Individual scores are provided in Table 1 of the supplementary material.

Participant demographic with clinical data and results of the neglect tests.

Note. USN+ = Left-sided neglect after right-hemisphere stroke; VR = Virtual Reality; Years of education: 'Low' corresponds to fewer than 10 years of education, including both school and higher education; 'Mid' corresponds to 11–14 years; and 'High' corresponds to 15 years or more.; NET: Neglect-Test (Fels & Geissner, 1997), SNT: Sensitive Neglect Test (Reinhart et al., 2016), CoC: Center of Cancellation (Rorden & Karnath, 2010).

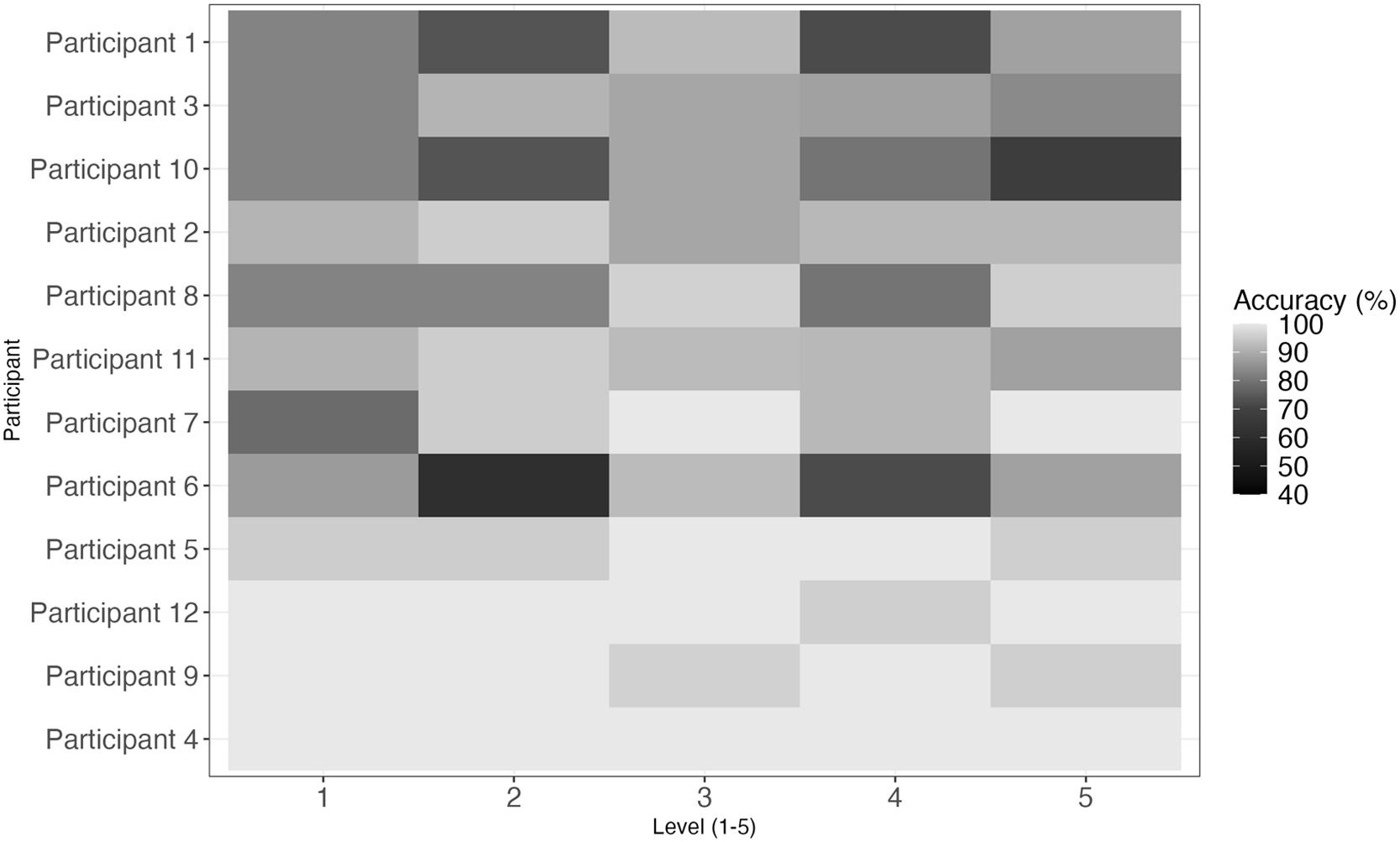

A LMM was conducted to examine the effects of level (1–5) and transport number (1–3) on the logit-transformed percentage of correctly transported objects, while accounting for variability between participants as a random effect. Due to a right-skewed distribution of percentages with values near 100 %, the data deviated from normality, necessitating a logit transformation of the percentages for analysis. Logit transformation was applied to address ceiling effects and differences in the maximum number of objects per level, improving the model's ability to explain variance in the data. Despite these adjustments, high variability was observed across participants, with some exhibiting ceiling effects while others showed level-dependent performance differences. A heat map (Fig. 4) visualizes accuracy across levels for each participant, highlighting these individual differences. Results revealed significant main effects for both level, F(4, 342) = 3.43, p = .009, and transport number, F(2, 342) = 6.91, p = .001. Significantly higher accuracy was observed at level 3 than level 1, b = 0.56, SE = 0.21, t(342) = 2.62, p = .009, while no differences were found between levels 4 and 5. Regarding transport number, both second transports (b = −0.35, SE = 0.17, t(342) = −2.11, p = .035) and third (b = −0.61, SE = 0.17, t(342) = −3.71, p < .001) were associated with fewer correctly transported objects compared to the first transport.

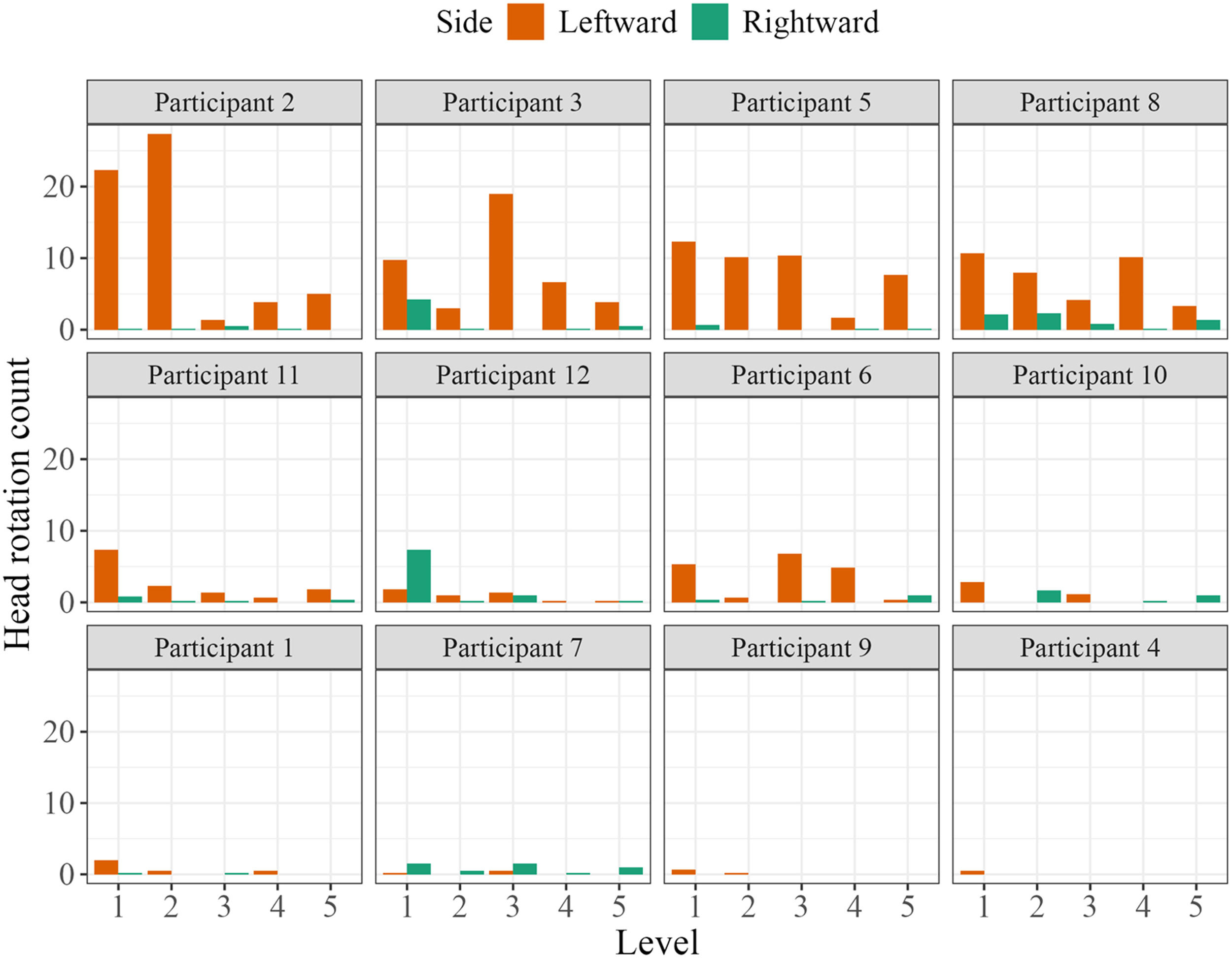

Immediate feedback for head rotationA LMM examined the effects of level (1–5) and side of head turn (left, right) on the number of head rotations with immediate feedback during the VR training. The model’s fixed effects explained a moderate amount of variance (pseudo-R² = 0.18 fixed effects, 0.34 overall). The intercept was significantly positive (b = 5.48, SE = 0.96, t = 5.72, p < .001). Participants generally made more left-sided than right-sided head rotations, b = −3.20, SE = 0.66, t = −4.85, p < .001 (movement back to the center was not counted), with a decreasing trend across experimental levels: left rotations decreased from level 1 (M = 6.31, SD = 8.22) to level 5 (M = 1.85, SD = 3.66), and similarly, right rotations decreased from level 1 (M = 1.45, SD = 2.97) to level 5 (M = 0.46, SD = 0.95). Compared to level 1, significantly fewer rotations occurred at level 4 (b = −2.65, SE = 1.04, t = −2.54, p = .01) and level 5 (b = −2.73, SE = 1.04, t = −2.61, p = .01). Despite a decreasing trend in head-turn feedback across levels, substantial interindividual variability was noted (Fig. 5). Random-effects analysis showed moderate variability between participants (SD intercept = 1.78), a residual SD of 3.62, and an ICC of 0.20, indicating meaningful between-participant differences.

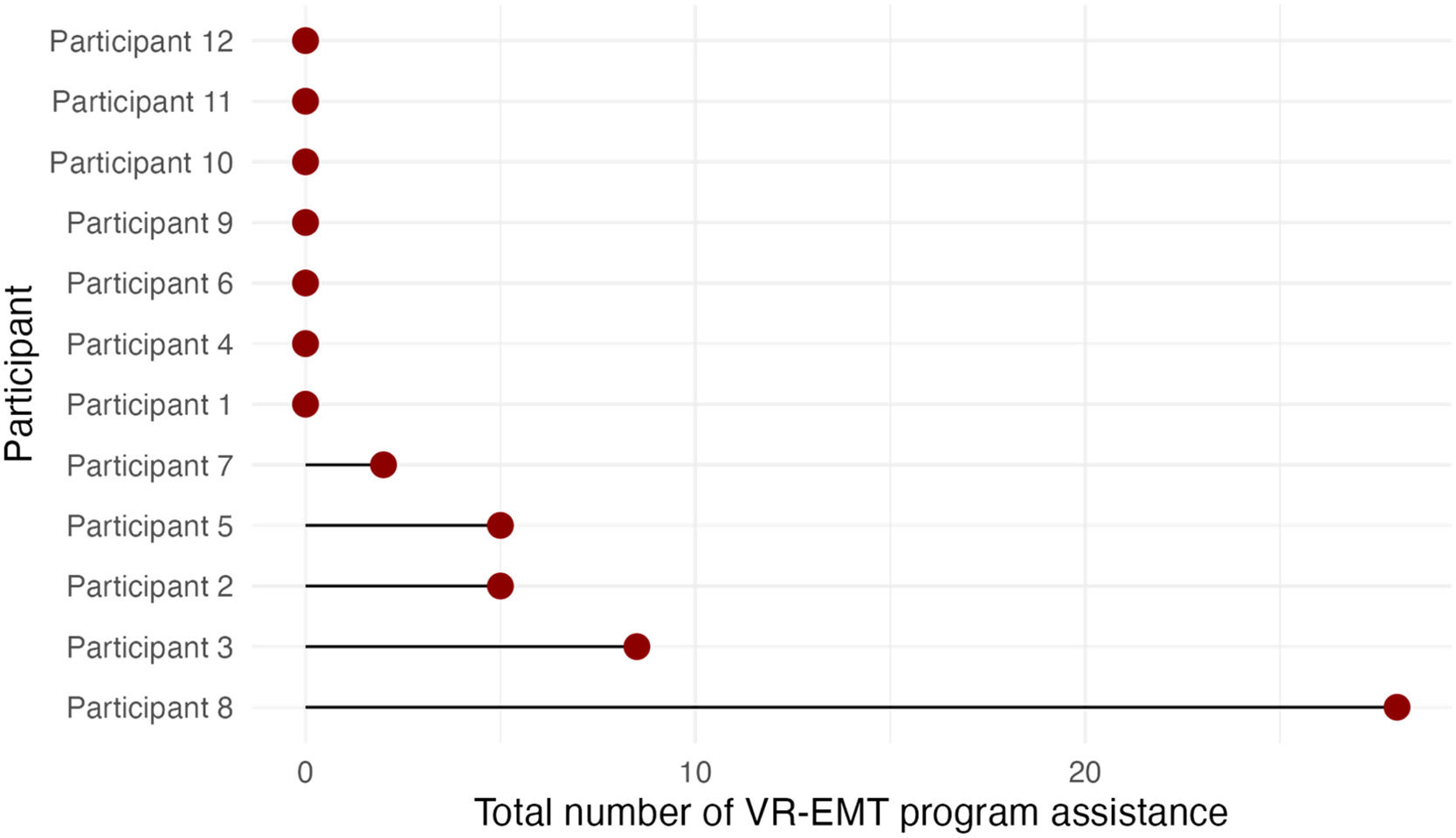

Additional program assistanceAutomatic program assistance due to sustained head deviation (>10 s) was required by 5 out of 12 participants, enabling independent task continuation. Due to the low overall frequency of these events, descriptive statistics are provided (Fig. 6). The number of assistances ranged from 0 to 8 per level, with a total count per participant summed across all levels ranging from 0 to 28. Notably, one participant showed a higher number of assistance events in level 1 (5/28) and level 4 (12/28). Importantly, all participants re‐centered their attention and heads without any intervention by the experimenter, allowing independent task continuation.

Usability and feasibilityPatients rated the VR training highly overall. The system was perceived as usable (M = 4.42, SD = 0.51) and provided strong comfort (M = 4.00, SD = 0.60), safety (M = 4.17, SD = 0.58), and enjoyment (M = 4.33, SD = 0.65). Immediate feedback mechanisms were especially valued; the green outline for correctly tracked objects was rated as helpful (M = 4.50, SD = 0.52), and the confirmation circles required for task continuation were considered highly manageable (M = 4.42, SD = 0.51). In addition, feedback on head rotation was perceived as beneficial (M = 4.58, SD = 0.67) and was associated with increased awareness of head deviations in daily life (M = 4.00, SD = 0.95) as well as a heightened tendency to turn their head during everyday tasks (M = 3.08, SD = 1.16). Table 2 in the supplementary material shows the USEQ scores for participants with and without hemianopia.

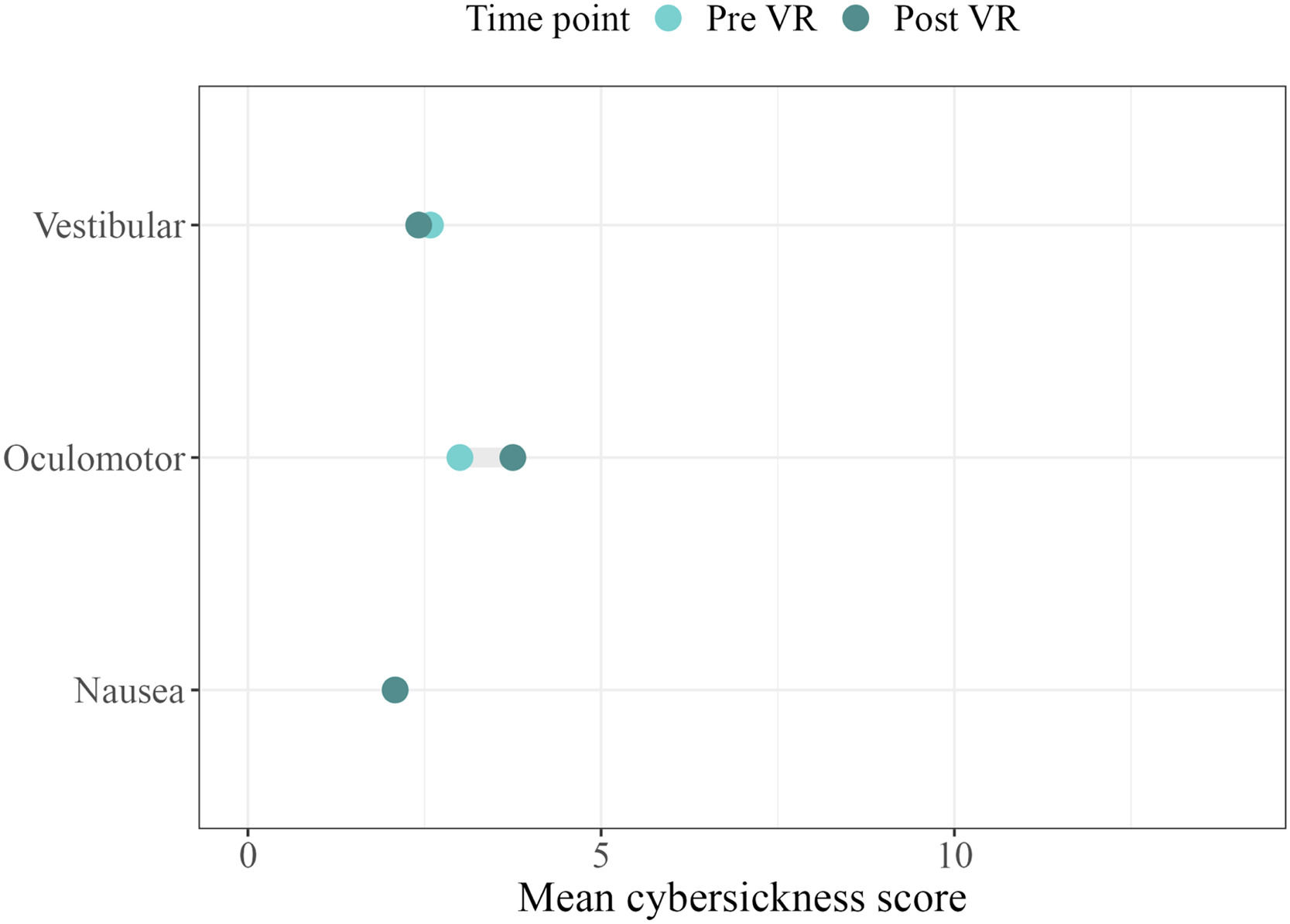

CSQ-VR. Comparing CSQ-VR scores before and after the first VR training session, a LMM revealed a significant main effect for the CSQ subfactor Oculomotor, b = 0.92, SE = 0.41, t(64) = 2.26, p = .027, indicating higher scores after the first VR training session. However, these minor increases in oculomotor symptoms arise from the items “Fatigue” and “Visual Discomfort”, which in our results range from 1 (no symptoms) to 4 (somewhat present; assigned once), contributing to the Oculomotor subfactor. No significant main effects were observed for vestibular symptoms, p = .223, or time of measurement (post), p > .999. Additionally, none of the interaction effects between CSQ factors and time of measurement reached statistical significance, p = .196 to p = .773). Furthermore, random effects showed participant-level variability (SD = 0.44) and residual variation (SD = 0.99). No adverse effects from VR-induced discomfort were observed or reported, and no participants dropped out because of cybersickness (Fig. 7).

Mean cybersickness scores before (Pre VR) and after (Post VR) the first VR neglect training session

Note. CSQ-VR items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (absent feeling) to 7 (extreme feeling). The questionnaire consists of six items assessing three symptom domains of cybersickness: vestibular, oculomotor, and nausea. Each subscore ranges from 0 (no cybersickness) to 14 (extreme cybersickness).

USEQ. An overview of the USEQ results is provided in the Likert plot shown in Fig. 8. The VR-EMT received an USEQ total score (range: 6–30) of Mdn = 24.50 (IQR = 24.00–27.25), reflecting a positive usability rating and user satisfaction. Patients, on average, reported strongly enjoying the use of the VR-EMT (Mdn = 5.00, IQR = 4.00–5.00), found it to be highly usable (Mdn = 4.00, IQR = 4.00–5.00), and considered the instructions to be very clear (Mdn = 5.00, IQR = 4.00–5.00). Physical comfort during the task was also rated favorably (Mdn = 4.00, IQR = 3.75–4.00). The task was evaluated ambivalently regarding its usability for rehabilitation purposes, with notable variability (Mdn = 4.00, IQR = 3.75–5.00).

Comparison of VR-EMT with traditional SPT. When comparing traditional SPT with VR-EMT (0–2 favoring SPT, 3 no preference, 4–5 favoring VR-EMT), patients tended to prefer VR-EMT, as reflected in the average preference score (M = 3.83, SD = 0.94). This was particularly evident for perceived usefulness in rehabilitation (M = 4.00, SD = 0.95), preferred training type (M = 3.75, SD = 0.97), head rotation correction (M = 3.50, SD = 0.90), suitability for home use (M = 3.42, SD = 0.79). Fig. 9 shows the absolute frequencies of responses for perceived usefulness in rehabilitation and overall training preference if participants had to choose a training method. Qualitative feedback highlighted several advantages of VR-EMT: participants valued the immediate feedback on progress, absent in traditional SPT, and generally preferred VR-EMT for its greater challenge and need for focus. They also noted that the system detected head movements better than orthoptists, providing a sense of closer monitoring. The novelty of VR-EMT was another appealing factor. Symptom-related feedback revealed mixed views: one participant found the red screen in VR-EMT distracting when looking left, favoring SPT. Others felt traditional SPT was simpler, while VR-EMT was more demanding. All participants expressed willingness for further VR training (M = 4.17, SD = 0.39).

Immediate effects on exploration and task behavior in the break phaseA LMM was fitted with percentage as the dependent variable, and break (1, 2, 3) and side (left,. right) as fixed factors, with random intercepts for participant. The model revealed a significant main effect of Side, with right-side gaze percentages being 44.01 % higher than left-side, b = 44.01, SE = 4.12, t(292) = 10.69, p < .001. In contrast, neither the main effect of break, F(2, 292) = 0.03, p = .975, nor the break × side interaction, F(2, 292) = 1.55, p = .215, reached significance (see Fig. 1, supplementary material). Notably, the variance of the random intercept was near zero, indicating minimal between-participant variability. These findings suggest that in free exploration scenes, participants predominantly directed their gaze toward the ipsilesional side, with no significant change in gaze distribution across the different breaks.

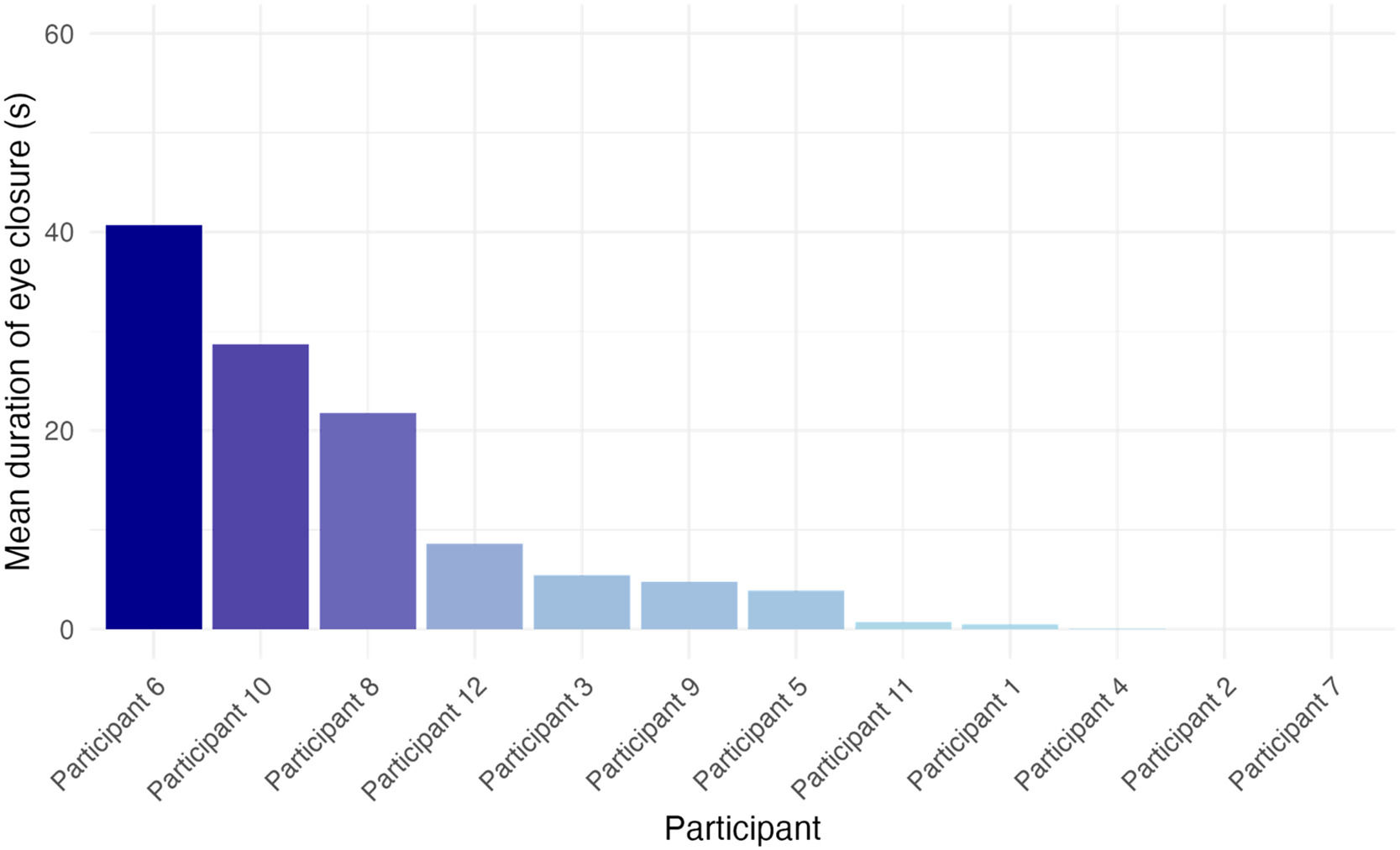

Resting time during the breakResting time was defined as cumulative eye closure longer than 0.5 s during task breaks. Each training level included three break phases without task demands or feedback. Participants’ average resting (eye-closure) time per break was short (M = 0.17 min, SD = 0.31). The distribution was highly skewed, with a median of 0.00, indicating that most breaks involved no rest. To examine the effects of task structure on rest behavior, we fitted a LMM with level and break as fixed effects and a random intercept for participant. The model revealed a significant increase in rest time at level 4 compared to level 1 (b = 0.112, SE = 0.036, p = .002). No other level or break effects reached significance (all p-values > 0.28; see Table 1). Pairwise comparisons indicated that level 4 was associated with significantly more rest than levels 1 to 3, respectively p = .002, p = .022, p = .038, but not level 5, p = .178. Break phase had no significant effect on rest duration.

The random intercept for participant showed substantial variance (Var = 0.045), confirming strong individual differences in resting behavior that were not accounted for by task structure alone. Interindividual differences were pronounced, as 8/12 participants showed signs of resting with high variability. Average resting time across breaks ranged from 0.00 to 21.74 s. The between-subject standard deviation (SD = 0.22 min) exceeded the overall mean, indicating that individual differences in disengagement behavior were more prominent than any task-related modulation (Fig. 10).

Performance decline across training blocksWe compared the percentage of correctly transported objects between training block 1 and block 3 across levels 1–5 using a LMM with training block as the fixed effect and random intercepts for participants. Accuracy significantly declined from block 1 (92.90 %) to block 3 (90.39 %), F(1107) = 5.03, p = .027. Standardized estimates yielded an intercept of 0.15 (95 % CI: –0.29 to 0.59) and a standardized effect for block 3 of –0.30 (95 % CI: –0.56 to –0.04), confirming the lower performance relative to block 1. In contrast, comparisons of immediate head rotation feedback between blocks 1 and 3 revealed no significant differences for head turns to the left (b = –0.63, SE = 1.57, t(107) = –0.40, p = .688) or to the right (b = –0.08, SE = 0.28, t(107) = –0.30, p = .766).

DiscussionThis proof-of-concept study evaluated a novel immersive VR-based neglect training for chronic post-stroke patients, integrating elements of smooth pursuit training (SPT). The VR training provided immediate visual and auditory feedback on both gaze and head orientation, which was associated with increased awareness of deficits and enabled rapid behavioral adjustments. Task performance declined with increasing difficulty level: object-transport accuracy dropped when additional elements, such as a higher number of distractors and conveyer belts, were introduced. Moreover, the automatic, immediate, and continuous feedback on head rotation enabled patients with deviating head turns to promptly adjust their orientation and continue the training without experimenter intervention. In terms of usability, the training was well tolerated, executable independently, and highly rated for comfort, safety, and overall system usability. Immediate feedback on head rotation was particularly appreciated, and most participants expressed a strong willingness to continue VR training. Notably, compared with traditional SPT, the immersive VR approach, with its enhanced real-time feedback and objective behavioral monitoring, was preferred by patients. Finally, analysis of exploratory behavior during breaks revealed a consistent ipsilesional gaze bias, while increased resting behavior and eye closure in some participants indicated training-related attentional decline or tiredness. Overall, these findings support VR-based SPT as an engaging and ecologically valid intervention for neglect rehabilitation.

Feedback and performance evaluationOur results revealed several important aspects regarding the performance and feedback mechanisms of the VR-EMT task. First, in terms of correctly transported objects, ceiling effects were observed for some patients, suggesting that the task was too easy for them, particularly in low levels. Accuracy was significantly higher in level 3 compared to level 1, which may reflect a training effect from practicing with a single conveyor belt, whereas no significant accuracy differences emerged between levels 4 and 5, likely indicating that additional challenging elements (e.g., extra conveyor belts and increased object density) effectively heightened task difficulty. Furthermore, accuracy tended to decrease over time within each level, indicating that attentional decline and increased distractions may cause patients to lose sight of the target object and interrupt the transport sequence. In future applications, this pattern could serve as a signal to initiate training breaks or to adapt session durations on an individual basis. Although the VR-EMT followed a fixed difficulty progression, the results indicate floor effects in some and ceiling effects in others. This underscores the need for adaptive task regulation with individually adjustable pauses, training intensity, and distractor complexity.

Immediate feedback was provided through real-time cues for deviating head rotation. In contrast to neglect-specific deviations of exploratory movements to the right observed in previous studies (see for instance Fruhmann-Berger & Karnath, 2005), patients in our study demonstrated a stronger tendency to turn their head to the left than to the right, possibly indicating compensatory head rotations to the contralesional side in chronic neglect. However, this may also stem from an interaction between neglect and hemianopia (Parton et al., 2004). A decreasing trend in head rotations was seen across levels, most notably when comparing the first level with levels 4 and 5, implying that patients were learned to compensate although task difficulty increased. However, considerable interindividual variability in head rotation feedback was noted, which may be related to differences in neglect severity.

Automated assistance was activated for five patients, indicating that immediate feedback was generally sufficient. However, additional support by the system was necessary in some cases, which increases the applicability for patients with varying levels of impairment. Notably, one patient exhibited increased assistance events in levels 1 and 4, likely due to the novelty of the task and the higher difficulty associated with level 4 conditions. Overall, these results underscore the significant impact of task complexity and transport conditions on object transport accuracy, highlighting the need for continuous, automated feedback during training, not only to improve patient performance and make training sessions independent of experimenter support, but also to support increased awareness of deficits and more effective therapist monitoring.

Usability and feasibilityOur results demonstrate that the VR-EMT neglect training exhibits both high usability and feasibility for neglect rehabilitation. While USEQ ratings of rehabilitation usefulness were for some items low, possibly due to some patients finding the task too easy or too challenging and noting minor image flickering, the system received very high ratings for comfort, safety, and overall ease of use. Cybersickness levels remained low, and any mild increases in oculomotor symptoms did not affect performance. Moreover, all patients navigated the task independently by following the tutorials and progressing without external assistance, highlighting its potential for home use. The integrated eye-tracking component, employed as the sole mode of interaction, provided automated, precise, and feedback-driven control that supported self-monitoring and offered therapists immediate, objective insights into attentional processes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use eye tracking as the only interaction modality in a VR-based neglect training context. Patients preferred the immersive VR-EMT over conventional SPT, likely due to the prompt, real-time feedback, engaging gamification elements, and the enhanced variability and real-world relevance of the VR training. These outcomes support the integration of VR-based training into routine clinical practice and its adaptation for home-based rehabilitation.

Advantages of VR-EMTThe VR-EMT paradigm offers distinct advantages over conventional methods for neglect rehabilitation. It provides immediate, real-time visual and auditory feedback that facilitates rapid behavioral adjustments, supports self-monitoring, and thereby may foster self-efficacy. Its integrated eye-tracking system delivers objective, individualized insights into neglect-specific behaviors, and further has the potential to enable adaptive task difficulty tailored to patient performance. In addition, the immersive, gamified environment was associated with higher self-reported motivation and relates more closely to real-life scenarios than traditional, repetitive SPT. Overall, this VR neglect training combines smooth pursuit, visual scanning, dual-task demands, and vestibular stimulation, complemented by immediate system-provided feedback and cueing. This innovative, patient-centered rehabilitation approach effectively integrates top-down and bottom-up mechanisms within an immersive virtual reality environment.

The VR training task combines several well-established elements of neglect rehabilitation, besides SPT, into a single, unified application. First, smooth pursuit is included by requiring patients to track leftward-moving objects, thereby promoting fluid eye movements essential for visual engagement. In tandem, visual scanning is actively stimulated through deliberate saccadic movements and fixations toward the neglected side, with a mandatory 3-s fixation on each target object, further enhancing attentional focus. Moreover, the task integrates motor and visual skills by incorporating a dual-task component, in which target objects shift positions across different conveyor belts, challenging both visual search and memory processes. Self-monitoring strategies provided by system feedback are also employed to minimize mistakes and training frustration, while vestibular stimulation induces an attentional bias toward the neglected side by leveraging its role in organizing subjective spatial coordinates.

LimitationsOur study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small and limited to chronic stroke patients with predominantly mild neglect, restricting generalizability, particularly to acute or subacute populations. As this was a feasibility study, the efficacy of the training to reduce neglect remains to be demonstrated in a clinical trial. Additionally, no clinical or healthy control groups were included, preventing direct comparisons. Second, we assessed only immediate, short-term effects over a relatively brief training period (10 sessions). Further research is required to evaluate the sustainability and generalizability of training effects. High baseline performance likely caused ceiling effects, reducing sensitivity to subtle performance changes; future implementations could employ computerized adaptive difficulty scaling to address this issue. Mild, task-irrelevant cybersickness symptoms were assessed only after the initial session, neglecting potential cumulative effects over subsequent sessions. Furthermore, the novelty and high subjective satisfaction associated with VR may have been due to motivational biases, complicating comparisons with traditional, known approaches. Third, the training was embedded in an interdisciplinary treatment schedule. Thus, external factors such as fatigue and learning effects from preceding therapies were not systematically controlled and may have influenced task performance and engagement. Finally, patient-reported transfer of VR training effects to everyday activities varied considerably, highlighting the need for further evaluation of ecological validity. The VR-EMT enables detailed behavioral observation, offering a basis to examine differential treatment effects across neglect subtypes in future studies.

Directions for future researchFuture studies should more fully leverage eye-tracking metrics. For instance, these data could be used to detect rest and lateral attention deficits, as some participants occasionally closed their eyes during breaks. The marked interindividual differences in resting times further underscore the need for such monitoring. Furthermore, real-time feedback alerting both therapists and patients when prolonged eye closure occurs may help maintain engagement during training or indicate when additional breaks are needed. Additionally, monitoring pupil dilation during training offers a valuable psychophysiological marker for the early detection of training fatigue and attentional decline, since pupil dynamics closely reflect cognitive effort, mental fatigue, and task engagement (Lisi et al., 2015). Moreover, the extensive eye-tracking data collected during training and break scenes should be used to quantify neglect-specific gaze behavior. Future analyses could focus on metrics such as spatial gaze distribution, gaze shift amplitudes, and oculomotor patterns to better characterize neglect-related behaviors and recovery trajectories.

To enhance personalization and sustain motivation, computerized adaptive testing could be employed to dynamically adjust individual task difficulty to prevent ceiling or floor effects during VR-EMT. Structured visual rest periods (e.g., short breaks with optional HMD removal) and individually tailored session lengths may further reduce visual fatigue. Adjustable parameters, such as belt speed, stimulus density, and visual complexity could enable progressive, individualized difficulty scaling. Future research should increase training frequency by implementing shorter, more frequent sessions and include larger, more diverse samples with clinical (e.g., patients with hemianopia and neglect) and healthy control groups. Finally, the VR-EMT paradigm could be adapted for bedside use during early post-stroke phases, as well as for standalone home-based applications, enhancing accessibility while reducing clinical workload.

ConclusionThis feasibility study demonstrated that immersive VR-based smooth pursuit training (SPT) is technically feasible, clinically applicable, well accepted, and subjectively preferred over traditional methods in chronic post-stroke neglect. Real-time visual and auditory feedback on gaze and head orientation enabled rapid behavioral adjustments, while the sole use of integrated eye tracking for interaction allowed for objective monitoring of neglect-specific behaviors. While no therapeutic effects can be concluded from this feasibility study, the system’s precise feedback and subjective preference highlight its potential for individualized interventions and remote application. As task performance declined with increasing difficulty, these findings confirm that task demands can be effectively modulated. As the first study to use eye tracking as the only interaction modality in VR neglect training, our results support its potential for clinical application, including home-based telerehabilitation. Future studies should evaluate clinical efficacy and investigate how eye-tracking data can inform attentional state monitoring in neglect.

EthicsThe study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Medical Faculty, University of Leipzig (Ethics code: 117/18-lk, March 5, 2020).

The authors report no conflict of interest.