A notable deficit in working memory (WM) is well established in schizophrenia. Nevertheless, the intricate relationship between various symptoms and WM impairment is still not fully understood. We use three distinct methodologies—symptom network analysis (SNA), Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling (CPM), and brain gene annotation enrichment analysis—to explore the connectome patterns that link WM deficits and symptoms, and their related gene expression.

Methods255 patients with schizophrenia were recruited as two distinct samples. SNA was used to pinpoint the core psychiatric symptoms influenced by WM performance. CPM identified the subnetwork of the functional connectome that was recruited under the 2-back load of the N-back WM task, and predicted the severity of the SNA-based key symptoms. Gene annotation enrichment analysis explored the likely molecular biological processes underlying the symptom-predictive functional WM network.

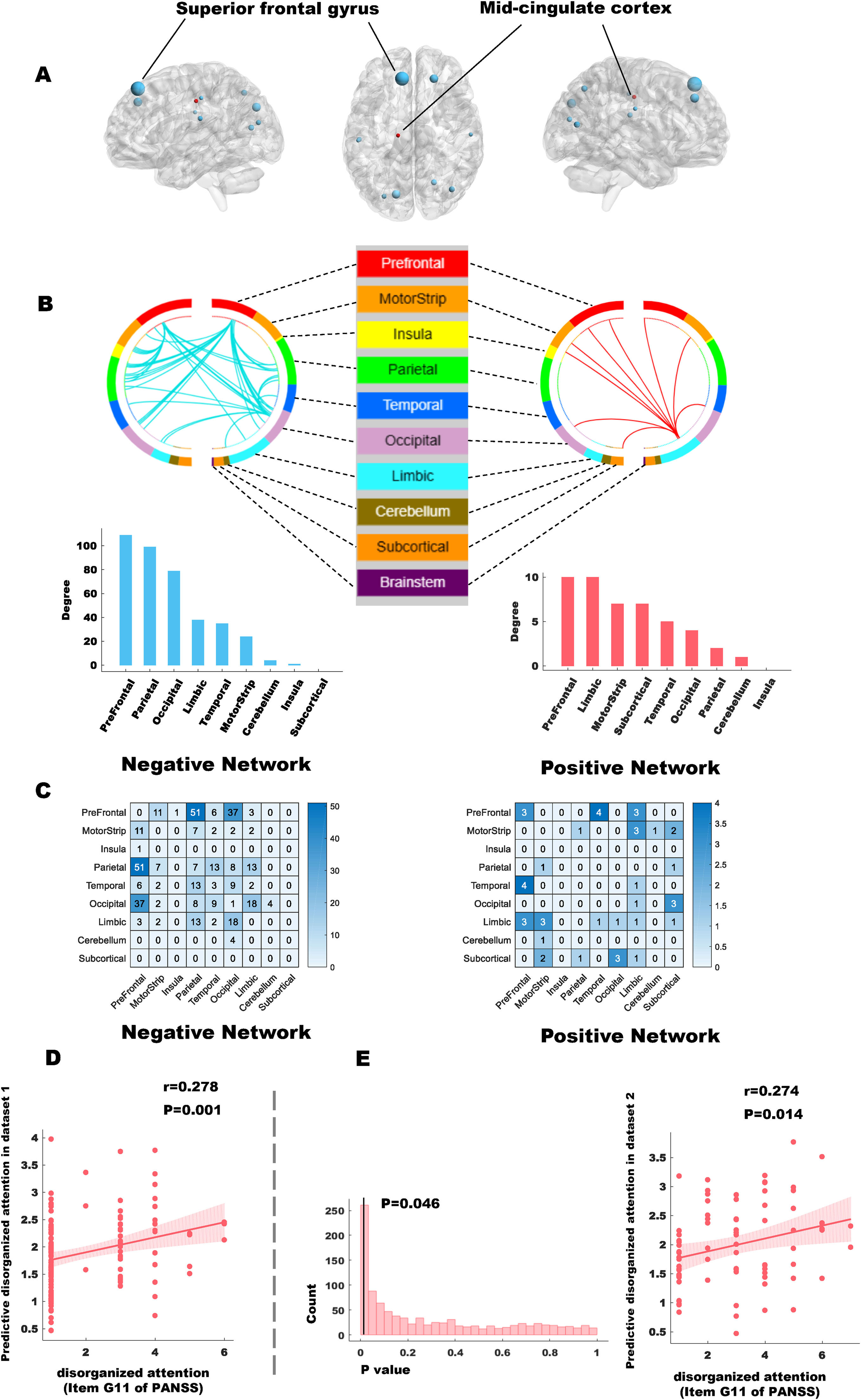

ResultsSNA revealed that disorganized attention (G11 of PANSS) is most closely linked to WM performance in schizophrenia. The WM-based connectome significantly predicted disorganized attention (r = 0.278, p = 0.001, permutation-p = 0.046), and this model was validated in the second dataset (r = 0.274, p = 0.014). The predictive network primarily involved the frontoparietal and frontolimbic networks. Gene enrichment analysis revealed a preferential role for cytoplasmic protein binding, indicating a potential molecular basis for the WM-related, symptom-predictive functional connectivity.

ConclusionsImpaired WM performance in schizophrenia relates to frontoparietal and frontolimbic connectivity and preferentially influences the severity of disorganized attention, a clinically observable phenomenon. The potential role of cytoplasmic protein binding in WM deficits and attentional disorganization in schizophrenia warrants further investigation.

Working memory (WM) deficits are one of the core cognitive impairments in schizophrenia (Baddeley, 1992) that profoundly influence clinical outcomes and daily functioning, often outweighing the severity of positive or negative symptoms per se (Fioravanti et al., 2012; Green et al., 2004). WM deficits are central to cognitive dysfunction and the associated symptom profile of schizophrenia (Eryilmaz et al., 2016).

Cognitive impairments in schizophrenia, particularly deficits in WM, have a profound impact not only on functional outcomes but also on treatment adherence. These impairments may interfere with patients’ capacity to comprehend, remember, and implement treatment plans, a challenge that is further exacerbated in the presence of comorbid substance use or severe psychopathological symptoms. Additionally, the adverse effects associated with antipsychotic medications can further diminish adherence. These associations are consistent with findings in affective disorders, where similar factors have been linked to treatment adherence (Pompili et al., 2013).

Beyond clinical and treatment implications, symptom expression and illness phenotype are also linked to psychosocial vulnerability, which has become more pronounced during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Disrupted services, social isolation, and increased stress during this period have exacerbated symptoms and impaired functioning in individuals with chronic psychiatric conditions (Ambrosetti et al., 2021).

The association between WM deficits and psychiatric symptoms may relate to the overlap in neural substrates influencing both symptom expression and WM deficits, particularly involving circuits connected to the prefrontal cortex (Barch & Ceaser, 2012). Among the wide array of symptoms of schizophrenia, it is unclear which symptoms are specifically dependent on WM deficits for their expression. Given the inter-dependent nature of individual symptoms, a network (“symptomics”) approach is necessary to uncover this link.

WM maintenance is a key component of cognitive control that requires systematic collaboration among whole-brain networks (Shine et al., 2016) with dopamine receptors acting as key regulatory signals (Durstewitz & Seamans, 2008). This collaboration primarily involves the brain regions of the frontal and parietal cortices, as well as the medial areas within the default mode network (DMN) (Ueltzhöffer et al., 2015). In schizophrenia, the collaborative mechanisms among different brain networks at the whole-brain level are known to be impaired (Mennigen et al., 2019). If WM dysfunction is fundamental to the symptom structure of schizophrenia, we can expect WM-associated brain functional networks to predict the burden of relevant symptoms in patients. We test this hypothesis using connectome-based predictive modeling, an approach that has been previously used successfully in schizotypy (Chen et al., 2023) and a broad set of cognitive functions in schizophrenia (Barron et al., 2021).

We have previously examined (in a partially overlapping sample), the relationship between brain networks implicated in WM deficits and symptom severity (especially, disorganized behavior) (Cheng et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024). This study, and several others, have utilized correlational approaches that tend to overfit the symptom data to brain network properties. Although this approach has partially elucidated the relevant neuroimaging mechanisms, generalizability has been limited. Further, the reliance on a single behavioral index (e.g., WM accuracy) to detect brain network correlates introduces confounding factors from unrelated variables (Kahan et al., 2016). As a result, these studies cannot conclusively determine whether the reported WM-related brain network changes are indeed the correlates of non-targeted symptoms that map onto WM deficits. Without predictive relationships that are replicable externally in a second dataset, the neural basis of psychiatric symptoms that relate to WM dysfunction remain obscure in schizophrenia.

To address this challenge, we first employed symptom network analysis (SNA), a reliable data-driven method widely used in recent psychopathology research, to identify the symptoms that most strongly correlated with WM deficits (“WM-related core psychiatric symptoms”) while controlling for other covariates. We expected disorganization-related symptoms to emerge as the most likely symptom candidate for WM deficits, based on prior observations (Cameron et al., 2002; Daban et al., 2003; Perlstein et al., 2001). Next, we adopted connectome-based predictive modeling (CPM) to investigate the brain functional connectivity associated with these symptoms during WM tasks, establishing a direct link between the relevant symptoms and WM-related functional connectivity. Finally, we used the human brain gene annotation atlas for GWAS analysis to explore the potential molecular biological mechanisms underlying this association.

CPM is a neuroimaging analysis method that predicts individual behavioral or biological characteristics by analyzing functional connectivity networks (Yuan et al., 2022). It has been shown to reliably predict cognitive functions or symptom levels and can be cross-validated in independent datasets, ensuring reliable and generalizable results (Shen et al., 2017). This enables reliable extraction of functional connectivity patterns that predict psychiatric symptoms.

The Allen Brain Atlas, used in this study, provides extensive genetic expression data in the human brain through in situ hybridization and high-throughput RNA sequencing, offering detailed spatial localization maps (Sunkin et al., 2013). These maps enable reverse inferences about genetic influences on specific brain regions via spatial correlation, hinting at the relevant genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying WM-related core psychiatric symptoms in the present study.

We aim to clarify the connection between the phenotypic (symptom expression) and endophenotypic (latent cognitive, genetic, and connectivity) aspects of schizophrenia in the domain of WM. As shown in Fig. 1, we combined SNA with CPM, and subsequently used the human brain gene annotation atlas for GWAS analysis followed by Allen Brain Atlas-based gene enrichment analysis to explore potential molecular mechanisms. Thus, we undertook a multi-level investigation into the complex relationships between WM and psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia. Based on prior literature and theoretical considerations, we expected that specific symptom dimensions—particularly those related to attention—might show closer associations with WM deficits, that these symptom patterns could be reflected in functional connectivity within higher-order control networks, and that related brain regions might be enriched for gene expression profiles linked to intracellular signaling and synaptic regulation.

MethodsStudy design and participantsThe current study cohort comprised two schizophrenia datasets. Dataset 1 contains 164 patients and dataset 2 contains 91 patients. Diagnoses were established according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for schizophrenia, confirmed through a Structured Clinical Interview conducted by qualified clinical psychiatrists. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplementary Material S1. Patients meeting the diagnostic and inclusion criteria first underwent an interview and assessment conducted by licensed psychiatrists to gather background information and complete the PANSS scale evaluation. On the same day, the patient was escorted to the fMRI scanning room, where the scan was performed by a certified radiology technician.

All participants were native Chinese speakers residing in China and were right-handed. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legal guardians in accordance with the protocol approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. The data reported here has a partial overlap with a study previously published by our research group (Wang et al., 2024) (91 subjects in the Philips dataset and 112 subjects in the Siemens dataset for both studies).

Psychiatric symptomsIn both the training and validation datasets, psychiatric symptoms were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), a standardized and validated instrument for evaluating the severity of schizophrenia symptoms (Kay et al., 1987). The PANSS consists of 30 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = absent to 7 = extreme), encompassing three subscales: the Positive Scale (7 items), the Negative Scale (7 items), and the General Psychopathology Scale (16 items). Total scores range from 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. The PANSS has demonstrated strong reliability and validity and remains one of the most widely used instruments in schizophrenia research. In the present study, item-level PANSS data were used for symptom network construction and further analyses linking symptoms to cognitive and neural correlates.

Magnetic resonance imaging data acquisition and preprocessingThe dataset 1 was acquired using a Siemens Allegra 3-T scanner, while the dataset 2 was obtained using a Philips Gyroscan Achieva 3.0 T scanner. The preprocessing of the fMRI data was conducted using the DPABI toolbox (Yan et al., 2016). Detailed parameters of the fMRI scans for both datasets, as well as the fMRI data preprocessing procedures, are provided in Supplementary Material S2.

Working memory task paradigm and task-based functional connectomeThe WM paradigm employed in this study was the N-back task, consisting of two different loads: “0-back” and “2-back” (Wang et al., 2025). Detailed information about the WM paradigm can be found in Supplementary Material S3. Given that the “0-back” condition is not considered a qualified WM task, only the data from the four blocks of the “2-back” load were extracted and concatenated for constructing the whole-brain functional connectome.

In addition, behavioral accuracy on the 2-back task was calculated for each participant as an index of WM performance. This measure was incorporated into the SNA as one of the nodes, along with all individual items from the PANSS scale, to explore which psychiatric symptom is most closely associated with WM performance. The symptom identified through this analysis was then used as the target variable in the subsequent CPM analysis.

Since the “0-back” load is not considered a valid WM task (Miller et al., 2009), only the “2-back” load was selected for the construction of the whole-brain functional connectome. To construct the task-based functional connectome, we adopted a node-based approach informed by a well-established brain atlas (Power et al., 2011). This atlas delineates 264 nodes, each corresponding to a 6-mm spherical region of interest. For each node, the average time series of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal under “2-back” load was extracted and concatenated. Pearson correlation coefficients were then computed between the time series of every pair of nodes, resulting in a 264 × 264 correlation matrix.

To ensure a more stable distribution of correlation values, Fisher’s z-transformation was applied. Furthermore, we accounted for potential confounding influences of demographic factors—specifically age, gender, years of education, and framewise-displacement (FD) by statistically controlling for these variables, yielding the final corrected functional connectome. Detailed procedures for constructing functional connectomes during the WM task are provided in Supplementary Material S4.

Symptom network analysisSNA was conducted to identify psychiatric symptoms most closely associated with WM performance. WM accuracy and all items of the PANSS scale were included as nodes, and the network was estimated using the EBICglasso method, which identifies stable associations between variables while controlling for spurious connections (Haslbeck & Waldorp, 2018). Node centrality was assessed using expected influence. The reliability of edge weights and their differences were evaluated using nonparametric bootstrap procedures. Detailed statistical procedures are provided in Supplementary Material S5.

Connectome-based predictive modeling (CPM) analysisBased on the symptom identified through SNA, we applied CPM to determine whether WM-related functional connectivity could predict symptom severity. Functional connectivity matrices during the 2-back task were used as input features. Using a leave-one-out cross-validation framework, edges significantly associated with the target symptom were selected to build predictive models. These were further divided into positively and negatively predictive networks. Model performance was validated using both permutation testing and an independent external dataset. Further methodological details, including thresholding strategies and statistical criteria, are available in Supplementary Material S6.

Human brain gene annotation enrichment analysisTo explore the molecular underpinnings of WM-related brain connectivity, we performed a gene annotation enrichment analysis using the Brain Annotation Toolbox (BAT) and the Allen Human Brain Atlas (Liu et al., 2019). Genes with spatial expression overlapping the predictive functional connectivity were identified, and subsequent enrichment analysis revealed biological pathways potentially involved in schizophrenia. Detailed procedures are provided in Supplementary Material S7.

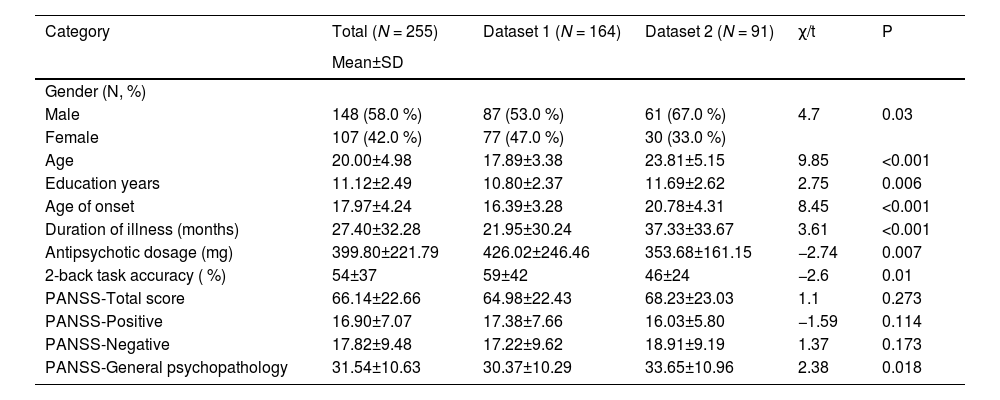

ResultsDescriptive statisticsSee Table 1 for the background information on the study sample. The overall study cohort consists slightly more of males (58.0 %) with an average age of 20.00±4.98 years with an 11.12±2.49 years duration of education. From a clinical perspective, patients had an early average age of onset (17.97±4.24 years), with a medium dosage of equivalent antipsychotic medication (399.80±221.79 mg/day).

Demographic, clinical, and neurocognitive information of participants.

Note: N, number of participants; SD, standard deviation; PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; Antipsychotic dosage refers to the dose equivalents for chlorpromazine.

Additionally, univariate analysis demonstrated significant differences in various demographic characteristics between patients in the two datasets. Specifically, the patients in dataset 1 were mostly females (47.0 % vs. 33.0 %, p = 0.03), younger (17.89±3.38 years vs. 23.81±5.15 years, p < 0.001), with fewer years of education (10.80±2.37 years vs. 11.69±2.62 years, p = 0.006), an earlier age of onset (16.39±3.28 years vs. 20.78±4.31 years, p < 0.001), and a shorter illness duration (21.95±30.24 months vs. 37.33±33.67 months, p < 0.001), though receiving higher doses of equivalent antipsychotic medications (426.02±246.46 mg/day vs. 353.68±161.15 mg/day, p = 0.007) compared to those in dataset 2. This facilitated the examination of the dataset 1 conclusions within dataset 2 with varied demographic backgrounds, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the outcomes.

Symptom network analysisBoth normality tests indicated that the matrix data used for network construction were non-normal. Therefore, this study opted for a nonparametric model based on the Gaussian copula (Zhao et al., 2012), which is suitable for handling non-normal data. Detailed information on the normality test results and model selection is provided in Supplementary Material S8.

The symptom network related to WM task performance is illustrated in Fig. 2. Notably, the symptom node with the most significant connection to the WM performance node was G11, with an edge weight of −0.05. The PANSS G11 item refers to poor attention, scored on the basis of the patient’s overall ability to sustain a conversation during a clinical interview. A failure to regulate attention during conversation is one of the most consistent items that define the symptom dimension of “disorganization” and loads along with conceptual disorganization and other behavioral features of cognitive disturbances (e.g., poor abstract thinking, volitional impairments) (Lehoux et al., 2009; Shafer & Dazzi, 2019). Our results suggested that, in the patients included in this study, poor attention (indexed by G11) is the symptom node most closely associated with poor WM performance.

The network structure of working memory task performance and psychiatric symptoms.

Note: Nodes that have a closer relationship with the working memory task accuracy (ACC) are placed in positions nearer to the ACC. According to the algorithm, completely isolated nodes (i.e., nodes without any edges connected to other nodes) have been removed. Consequently, the nodes G5 (Mannerisms and posturing) and G10 (Disorientation) were excluded from the network.

The red lines represent positive correlations. The green lines represent negative correlations. The line thickness represents the strength of the connection between symptom nodes. The edge encircled by a red dashed line represents the only edge between a psychiatric symptom node and working memory task performance within the network.

The expected influence of nodes in the network is presented in Supplementary Material S9. Although disorganized attention does not rank highly in terms of node importance within the overall psychiatric symptom network of schizophrenia patients, they are the symptom most closely associated with WM and functions as a hub linking WM to other psychiatric symptoms. Based on the edge weights, among the edges between disorganized attention and other psychiatric symptom nodes, disorganized attention (G11) is most strongly associated with other features of disorganization - volitional impairment (G13) and difficulties in abstract thinking (N5). This suggests that WM impairment relates to disorganized attention i.e. clinically notable inattention that disrupts the volitional and executive control processes which in turn influence other downstream psychotic symptoms. The detailed edge weight matrix is shown in Supplementary Material S10.

The accuracy assessment of edge weights revealed that the 95 % confidence intervals obtained from the non-parametric bootstrap tests were narrow, indicating reliable edge estimates in the network construction process. Furthermore, the examination of edge weight differences demonstrated statistically robust edge weights, including the edge between WM performance and disorganized attention (i.e., accuracy-G11), which was of particular interest in this study. These findings collectively indicate the reliability of the SNA results. Details are shown in Supplementary Material S11-S12.

CPM analysisThe results of the CPM analysis indicate that the combined model can effectively predict disorganized attention (r = 0.278, df=134, p = 0.001), as shown in Fig. 3[D]. Neither the positive nor the negative predictive models alone demonstrated statistically significant predictive value for G11 disorganized attention (positive model: r = 0.1448, df=134, p = 0.094; negative model: r = 0.121, df=134, p = 0.163).

The CPM analysis predicts disorganized attention based on functional connectivity. (A) Anatomical localization of the network predictive of disorganized attention; (B) Negative and positive predictive network for disorganized attention; (C) Functional connections within the identified networks as classified by the Power atlas. (D) Validation of CPM model reliability and predictive performance on disorganized attention.

In all iterations, edges that exhibited predictive ability in more than half of the iterations were classified as consensus connectivity. This means that, for consensus connectivity to be established, an edge must demonstrate predictive relevance in more than half of prediction iterations.

CPM network anatomyThe positively predictive and negatively predictive networks of attention scores based on connectivity between macroscale brain regions are summarized in Fig. 3. The spatial extent of both positive and negative networks together included 198 edges (22 positive, 176 negative). The consensus connections of the negative networks are primarily located in the prefrontal, parietal, and occipital lobes, whereas those of the positive networks are predominantly found in the prefrontal, limbic, and motor cortex.

To further determine the predictive value of different brain regions for the target symptom, we ranked the brain regions based on their node degree (i.e., the number of consensus connections between a specific node and other nodes in the brain network). The highest degree nodes (i.e., nodes with a degree greater than 10) within the negative network include the left and right superior frontal gyrus (SFG), cuneus, right superior parietal lobule, left and right middle occipital gyrus, left postcentral gyrus, right supramarginal gyrus, and inferior parietal lobule. In the positive network, the mid-cingulate cortex (MCC) is the only node with a degree greater than 10.

Validation analysisInternal validation; We conducted permutation tests (1000 iterations) for the combined model, which revealed that the observed result significantly exceeded chance expectations (p = 0.046; refer to Fig. 3[D]).

External validation; For the external validation using dataset 2, we also employed the item G11 of the PANSS scale as the predictor. We observed the constructed CPM model in dataset 1 can significantly predict disorganized attention in dataset 2 (r= 0.274, p= 0.014; see Fig. 3[D]).

Human brain gene annotation enrichment analysisThe results of the enrichment analysis indicate that numerous enrichments of statistical significance were identified across various database components. Notably, the most pronounced enrichments were observed in the cellular component (CC), specifically in the cytoplasm, and in the molecular function (MF), particularly in protein binding. Details are shown in Fig. 4.

Results of human brain gene annotation enrichment analysis.

Note: The enrichment analysis was conducted using the Gene Ontology (GO) database, specifically focusing on the biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) categories for Homo sapiens (Hsa) sets. Subsequently, enrichment analysis of metabolic pathways was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database for Homo sapiens (Hsa) sets.

This study identified disorganized attention (G11) as the core psychiatric symptom most strongly associated with WM performance in schizophrenia. Functional connectivity within the frontoparietal and frontolimbic networks during WM tasks significantly predicted the severity of this attentional deficit, as revealed by CPM. These predictive patterns were further validated in an independent sample, supporting their generalizability. At the molecular level, gene enrichment analysis indicated that the predictive network was associated with cytoplasmic protein-binding processes, potentially implicating dopamine-related intracellular signaling pathways. Combining SNA, CPM, and transcriptomic analysis, this study delineates how disorganized attention may serve as a behavioral and neural bridge linking working memory deficits with broader symptom dimensions in schizophrenia.

To the best of our knowledge, our study innovatively integrates SNA, CPM, and brain transcriptomic data to comprehensively explore the behavioral, neural, and molecular correlates of WM deficits in schizophrenia. While prior studies have linked various symptoms to WM impairment (Jenkins et al., 2018), they have not clarified which symptoms are most strongly involved or how brain and molecular systems underlie these associations. By combining network-based methods and multilevel data, this study offers new insight into how disorganized attention bridges cognitive dysfunction and broader symptom expression in schizophrenia.

Though disorganized attention does not occupy a top position in terms of centrality within the broader psychiatric symptom network of schizophrenia patients, they are the symptom most strongly linked to WM. As a hub node, disorganized attention link WM with other psychiatric symptoms. Consequently, disorganized attention is a key target for clinical intervention in schizophrenia. Additionally, recent perspectives suggest that WM serves as the foundation for complex thought processes and volitional control (Miller et al., 2018). Our study indicates that this relationship may be mediated through the influence of WM on clinically detectable inattention.

These findings raise the possibility that disorganized attention may act as a cognitive and neural intermediary through which WM deficits influence broader symptom expression in schizophrenia. One plausible hypothesis is that impaired WM function leads to inefficient top-down attentional control, resulting in disorganized attention that is observable in clinical assessments. This attentional inefficiency may reflect disrupted dynamic allocation of limited cognitive resources, possibly mediated by functional disconnection within the frontoparietal network (FPN). Prior models have emphasized the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in coordinating attention and executive function through top-down modulation (Duncan et al., 2008). Therefore, disorganized attention may serve as a measurable behavioral expression of underlying resource allocation failures driven by WM deficits and FPN dysconnectivity. This hypothetical mediating role warrants further investigation using longitudinal or mediation-based analytic approaches.

The CPM analysis suggests that lower connectivity of the SFG, part of the DLPFC within the FPN, predicted poorer attention (higher G11 scores). FPN has been proven to be pivotal in a range of cognitive functions, encompassing WM and attention (Martínez et al., 2013). Furthermore, the impairment of WM observed in schizophrenia is linked to disturbances in the functional connectivity within the FPN (Nielsen et al., 2017).

According to Duncan et al., the close relationship between WM and attention (measured using constrained cognitive tests) is specifically reflected in the guidance of attention resources by WM (Duncan et al., 2008), which aligns with the top-down attention regulation mechanisms orchestrated by the DLPFC of FPN. Overall, the results of this study emphasize the role of DLPFC in WM deficits as well as disorganized attention in schizophrenia. Furthermore, the occipital and parietal lobes also exhibit significant negative predictive ability concerning disorganized attention. These regions collaborate within the dorsal attention network (DAN) (Vossel et al., 2014), with the occipital lobe processing visual information and the parietal lobe facilitating spatial attention and integration. This collaboration is crucial for top-down attention control (Luck & Gold, 2008) and is activated visually-based attention-related cognitive tasks, including WM tasks. This suggests that certain physical treatments (e.g., magnetic stimulation) applied to DLPFC or parietal regions, if effective in alleviating WM deficits, may improve disorganized attention in schizophrenia.

The CPM analysis also highlighted the role of MCC - a pivotal hub intersecting multiple brain networks associated with executive functions and attention allocation, such as the salience network, the FPN, the ventral attention network, and the cingulo-opercular control network. Its central role allows the MCC to integrate information from various brain networks to facilitate goal-directed behaviors, crucial for cognitive tasks, including WM tasks. The positive association between the MCC and disorganized attention observed in this study suggests a link between the integration of multiple brain networks and the allocation of attentional resources during WM tasks. Given previous research showing that dynamic integration of brain networks is associated with accurate WM task execution (Shine et al., 2016), we speculate that higher connectivity of MCC predicting disorganized attention may reflect a compensatory mechanism. Specifically, more severe disorganized attention in schizophrenia may require the MCC to optimize integration across multiple networks to meet cognitive task demands. However, this compensatory mechanism is likely inefficient, failing to meet cognitive demands, resulting in poorer performance compared to healthy individuals.

Enrichment analysis indicates that genes linked to predictive networks for disorganized attention are enriched in cytoplasmic components and protein binding functions. These findings likely relate to the cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling pathway that is relevant to dopaminergic neurotransmission. Firstly, WM impairment in schizophrenia is associated with dopamine receptor dysfunction (Durstewitz & Seamans, 2008). Dopamine signaling, particularly through the D1 and D2 receptors, plays a pivotal role in modulating cognitive functions such as attention and WM, both of which are often disrupted in schizophrenia. Secondly, the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway, regulated by dopamine receptors, involves schizophrenia-related synaptic genes (e.g., CREB1, CREM, PPP3CB) (Forero et al., 2016). Thirdly, key steps in this pathway occur in the cytoplasm and involve protein interactions (e.g., cAMP production, CREB phosphorylation) (Boyd & Mailman, 2012). These processes depend on protein binding functions that, when disrupted, could impair normal signaling cascades that are likely to be relevant in maintaining neural activity underlying sustained attention that is disrupted in schizophrenia. These findings offer a molecular framework for experimental studies examining the predictive networks relevant for attention and WM.

Although elements of the cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling cascade have been implicated in schizophrenia and cognitive dysfunction in prior studies, our findings extend this literature by specifically linking these molecular processes to a brain network predictive of disorganized attention during WM performance. This suggests that genes involved in cytoplasmic protein binding and dopaminergic intracellular signaling may represent not only mechanistic candidates, but also potential therapeutic targets for WM deficits in schizophrenia. Future studies integrating patient-derived transcriptomic data or pharmacological modulation of these pathways could further elucidate their functional roles in WM deficits.

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. First, although we validated the predictive model in an independent dataset with greater heterogeneity (e.g., sex, illness duration, education level, and medication dosage), both datasets consisted exclusively of Chinese individuals and predominantly included patients in the early phase of illness. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to broader or more chronic populations. Second, the cross-sectional design restricts our ability to examine changes in WM deficits and symptom profiles over time. While our findings suggest a link between disorganized attention and WM-related brain connectivity, longitudinal studies are needed to determine the stability, progression, and potential causal direction of these relationships.

Third, although the sample size was sufficient for the current analytic approach, it remains modest, and the possibility of false negatives in network estimation cannot be fully excluded. Larger-scale studies may enhance the stability and reproducibility of network-based findings. Lastly, while our study provides insight into the molecular mechanisms associated with WM-related brain networks, gene expression data were derived from healthy brain atlases, which may not fully reflect transcriptional patterns in schizophrenia. Future studies incorporating patient-derived molecular data will be necessary to confirm these findings. Together, these limitations suggest that while our conclusions are promising, they should be interpreted with caution and validated in more diverse and longitudinal samples.

ConclusionThese findings suggest that disorganized attention serves as a clinically observable bridge between WM impairment and broader symptom expression in schizophrenia. Its severity can be predicted by functional connectivity within frontoparietal and frontolimbic networks during a WM task, with potential molecular correlates involving cytoplasmic protein-binding processes related to dopamine receptor signaling. By integrating symptom-level analysis, task-based brain connectivity, and transcriptomic profiles, this study highlights disorganized attention as both a cognitive and neurobiological marker of dysfunction. These insights may inform more targeted cognitive interventions and help refine transdiagnostic models of schizophrenia. While the findings are based on early-phase Chinese samples, the consistency across two datasets suggests potential generalizability, which future cross-cultural and longitudinal studies should further examine.

ContributorsZL and JiY designed the study. FW, JuY, FS, ZF, and PC acquired the data. PC, and JiY analyzed the data. PC and JiY wrote the manuscript. LP interpreted the results, guided re-analysis as needed, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

FundingThis work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82201663 to JiY; 82071506 to ZL) and the Training Program for Excellent Young Innovators of Changsha (kq2306008 to JiY). Palaniyappan’s research is supported by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded to the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University (through a New Investigator Supplement to LP) and Monique H, Bourgeois Chair in Developmental Disorders. He receives a salary award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé (FROS).

These funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data sharing statementThe data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

LP reports personal fees for serving as chief editor from the Canadian Medical Association Journals, speaker/consultant fee from Janssen Canada and Otsuka Canada, SPMM Course Limited, UK, Canadian Psychiatric Association; book royalties from Oxford University Press; investigator-initiated educational grants from Janssen Canada, Sunovion and Otsuka Canada outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

The authors would like to thank all participants in this study.