This paper analyses the career aspirations of Austrian flexpatriates and expatriates. Conceptually, the article applies a framework using career anchors and internal career orientations. Empirically, we build on a variant of content analysis of 40 semi-structured interviews with 40 Austrian internationally mobile employees working in Eastern and Western European countries. The results show the existence of both traditional and new career aspirations. Most important to our sample are aspirations revolving around Management and Hierarchy, Internationalism and Entrepreneurial Creativity; for flexpatriates we find specifics regarding Freedom, Getting High and a new aspiration referred to as Celebrity; for expatriates particularities concern Balance, Pure Challenge and Skills and Knowledge. Generalizability of our findings is limited due to the interpretative nature of the study, the sample structure, and cross-sectional design.

Since the 1960s the number of multinational companies and types of interaction across borders have increased (e.g., Peiperl & Jonsen, 2007). Multinational companies’ international business strategies depend, among others, on an internationally mobile workforce (e.g., McNulty & De Cieri, 2011; Thomas, Lazarova, & Inkson, 2005). Hence it has become important to grasp the specifics of this workforce segment. Particularly, a better understanding of career perceptions among internationally mobile employees (IMEs) is critical since recent studies suggest a possible change in career values, motives and attitudes that could be responsible for low retention rates of international assignees (e.g., McNulty & De Cieri, 2011; Stahl, Miller, & Tung, 2002). Career aspirations are a core element of career perceptions because they govern individual career behavior (e.g., Derr & Laurent, 1989; Schein, 1996). It is vital to learn more about IMEs’ subjective career values to set adequate initiatives to retain talent, skills and know-how, create efficient HR programs and positively contribute to an organization's strategy and overall performance (e.g., Stahl, Miller, Einfalt, & Tung, 2000).

Previous research in this area nearly primarily covers traditional expatriates, i.e. assignees who move abroad for one to five years, often with their families (e.g., Mayerhofer, Müller, & Schmidt, 2011; Mayrhofer, Sparrow, & Zimmermann, 2008; Welch, Welch, & Worm, 2007), and has a strong focus on the U.S. Alternative forms of international working (for an overview see Mayrhofer, Reichel, & Sparrow, 2012) such as flexpatriation, i.e. frequent and regular business trips abroad without relocating (Mayerhofer, Hartmann, & Herbert, 2004), have received much less attention (Mayerhofer et al., 2011; Welch et al., 2007). Likewise, much of the research focuses on the situation outside of Europe (Scullion & Brewster, 2001). Yet, these alternative forms offer an important option for multinational corporations, especially when they operate in Europe. They may be better suited “to a global environment of highly efficient transport systems, growing availability of skilled local staff, and internet-based communication” (Bonache, Brewster, & Suutari, 2007: 5). Particularly in Europe “Euro-commuting” and frequent flying have increased in popularity due to relatively short distances (Collings, Scullion, & Morley, 2007).

Our paper responds to this knowledge gap. It analyses the career aspirations of flexpatriates in the European context, using classical expatriates as a group of comparison. Although there are many different definitions for international assignments and traveling (Shaffer, Kraimer, Chen, & Bolino, 2012) we decided to base our research group on the definition provided by Mayerhofer et al. (2004). The main criteria for differentiation among these two target groups for this paper is full relocation of one's center of life/vital interest and the commitment to frequent traveling. Both flexpatriate-types (frequent flyers and international commuters) fulfill these criteria in our case. The flexpatriate-sample travels on average 4.7 times a month for a duration of 3 days on average (see Table 2a for more details).

Conceptually, we draw upon two well-established concepts in career research, career anchors (Schein, 1977, 1996) and internal career orientations (Derr, 1986a). Based on 40 semi-structured interviews we apply content analysis (Mayring, 2003) and a variant of constant comparative method (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) to inductively elaborate the core categories of career aspirations among Austrian flexpatriates.

Our paper offers three main contributions. First, our results yield more insight into the still under-researched field of flexpatriates by showing particularities in their career aspirations compared to expatriates. This also provides a better basis for action of both human resource management (HRM) and career counseling by responding to changes in international mobility patterns. Second, the paper integrates and extends the career anchor and internal career orientation frameworks. In doing so, we strengthen the theoretical foundation of research on international mobility. Third, our study deepens the understanding of international mobility in Europe. In this way, we contribute to the discussion about contextualizing HRM and career research and balancing results from North America with a more global view.

Conceptual background and literature reviewCareer anchors and internal career orientationsCareer is seen as a “sequence of positions occupied by a person during the course of a lifetime” (Super, 1980: 282). Beyond this objective perspective career also includes subjective aspects and is understood as “the evolving sequence of work experience over time” (Arthur, Hall, & Lawrence, 1989: 8). Closely linked to career is career success, described as “the positive psychological or work-related outcomes or achievements one has accumulated as a result of one's work experiences” (Judge, Cable, Boudreau, & Bretz, 1995: 486). Both career and career success have objective components observed from outside, and internal components perceived from within (Hughes, 1937). Individuals’ perceptions of career and career success may influence what they aspire to in their careers, i.e. their career anchors (Schein, 1977, 1996) and internal career orientations (Derr, 1986a; Derr & Laurent, 1989).

Career anchors are an occupational self-concept that “serves to guide, constrain, stabilize and integrate the person's career” (Schein, 1978: 127). They consist “of (1) self-perceived talents and abilities, (2) basic values, and, most important, (3) the evolved sense of motives and needs as they pertain to the career” (Schein, 1996: 80). Career anchors are shaped by career and life experiences and consist of a person's non-negotiable values and motives when making a decision. As self-concepts, career anchors are a stabilizing force that guides individuals throughout career and life trajectories (Schein, 1996). Results have shown that most individuals have multiple anchors, primary and secondary, that may change through their career and life stages (e.g., Feldman & Bolino, 1996). Schein (1996) finds that varying needs of individuals underlie different career anchors and that the dominant anchor may change with distinct life phases and decisions. Originally, Schein (1977) presents five anchors: Autonomy/Independence, Security/Stability, Technical–Functional Competence, General Managerial Competence, and Entrepreneurial Creativity. Later, he adds three additional anchors: Service or Dedication to a Cause, Pure Challenge, and Lifestyle (e.g., Schein, 1990). Suutari and Taka (2004) introduce an anchor for international mobility, Internationalism.

Building on the concept of career anchor, Derr (1986a) develops the concept of internal career orientations. The term traces back to DeLong (1982), “meaning the capacity to select certain features of an occupation for investment, according to one's own motives, interests, and competencies” (Kim, 2004: 597). It emphasizes “a person's own subjective idea about work life and his or her role within it” (Derr & Laurent, 1989: 455) and internal perceptions of career and career success with a focus primarily on individual expectations, career needs and aspirations, all of which have a major impact on career decisions and evaluations of one's own career or career success (Chompookum & Derr, 2004; Derr, 1986b; Derr & Laurent, 1989). Internal career orientations are the product of one's “motives, values, talents, and personal constraints” (Chompookum & Derr, 2004: 409). Hence it not only concerns what people desire or believe to be important, but also what they perceive they can do best. Derr (1986b) identifies five internal career orientations: Getting Free, Getting Secure, Getting Balanced, Getting Ahead, and Getting High.

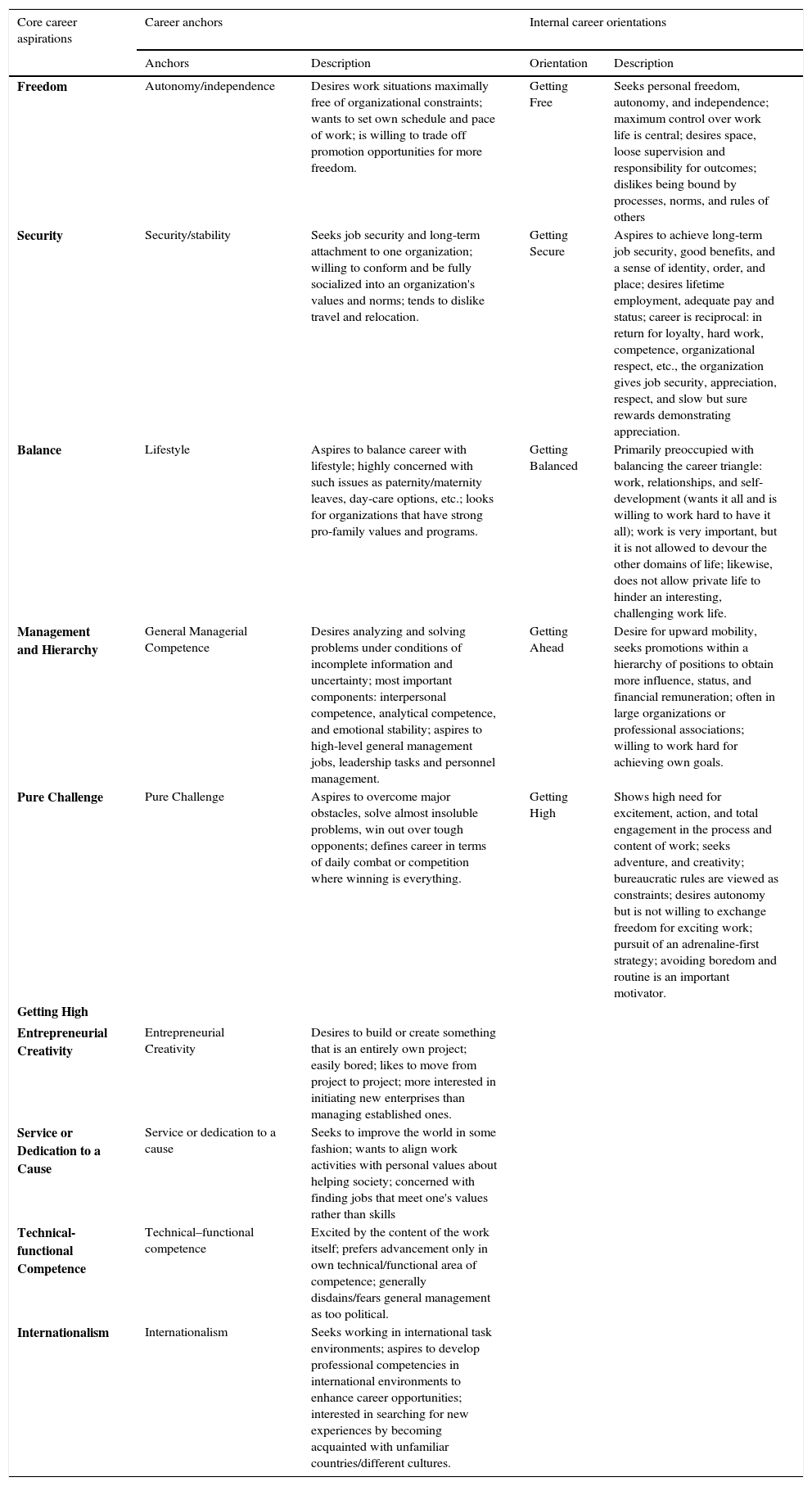

Both concepts are widely used (Arthur et al., 1989; Gunz & Peiperl, 2007; Ituma & Simpson, 2007; for studies of career anchors in the international field see Cerdin & Pargneux, 2010 for expatriates, Suutari & Taka (2004) for global leaders; for internal career orientations of expatriates see Siljanen, 2007). Table 1 gives an overview about major characteristics and a possible integration.

Integrating career anchor and internal career orientation theories.

| Core career aspirations | Career anchors | Internal career orientations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchors | Description | Orientation | Description | |

| Freedom | Autonomy/independence | Desires work situations maximally free of organizational constraints; wants to set own schedule and pace of work; is willing to trade off promotion opportunities for more freedom. | Getting Free | Seeks personal freedom, autonomy, and independence; maximum control over work life is central; desires space, loose supervision and responsibility for outcomes; dislikes being bound by processes, norms, and rules of others |

| Security | Security/stability | Seeks job security and long-term attachment to one organization; willing to conform and be fully socialized into an organization's values and norms; tends to dislike travel and relocation. | Getting Secure | Aspires to achieve long-term job security, good benefits, and a sense of identity, order, and place; desires lifetime employment, adequate pay and status; career is reciprocal: in return for loyalty, hard work, competence, organizational respect, etc., the organization gives job security, appreciation, respect, and slow but sure rewards demonstrating appreciation. |

| Balance | Lifestyle | Aspires to balance career with lifestyle; highly concerned with such issues as paternity/maternity leaves, day-care options, etc.; looks for organizations that have strong pro-family values and programs. | Getting Balanced | Primarily preoccupied with balancing the career triangle: work, relationships, and self-development (wants it all and is willing to work hard to have it all); work is very important, but it is not allowed to devour the other domains of life; likewise, does not allow private life to hinder an interesting, challenging work life. |

| Management and Hierarchy | General Managerial Competence | Desires analyzing and solving problems under conditions of incomplete information and uncertainty; most important components: interpersonal competence, analytical competence, and emotional stability; aspires to high-level general management jobs, leadership tasks and personnel management. | Getting Ahead | Desire for upward mobility, seeks promotions within a hierarchy of positions to obtain more influence, status, and financial remuneration; often in large organizations or professional associations; willing to work hard for achieving own goals. |

| Pure Challenge | Pure Challenge | Aspires to overcome major obstacles, solve almost insoluble problems, win out over tough opponents; defines career in terms of daily combat or competition where winning is everything. | Getting High | Shows high need for excitement, action, and total engagement in the process and content of work; seeks adventure, and creativity; bureaucratic rules are viewed as constraints; desires autonomy but is not willing to exchange freedom for exciting work; pursuit of an adrenaline-first strategy; avoiding boredom and routine is an important motivator. |

| Getting High | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Creativity | Entrepreneurial Creativity | Desires to build or create something that is an entirely own project; easily bored; likes to move from project to project; more interested in initiating new enterprises than managing established ones. | ||

| Service or Dedication to a Cause | Service or dedication to a cause | Seeks to improve the world in some fashion; wants to align work activities with personal values about helping society; concerned with finding jobs that meet one's values rather than skills | ||

| Technical-functional Competence | Technical–functional competence | Excited by the content of the work itself; prefers advancement only in own technical/functional area of competence; generally disdains/fears general management as too political. | ||

| Internationalism | Internationalism | Seeks working in international task environments; aspires to develop professional competencies in international environments to enhance career opportunities; interested in searching for new experiences by becoming acquainted with unfamiliar countries/different cultures. | ||

Sources: Career Anchors: Schein (1977: 53ff.; 1996: 80ff.; 1990); Suutari and Taka (2004): 836; Internal Career Orientations: Chompookum and Derr (2004): 408–409; Carlson et al. (2003): 104–105; Derr (1986b).

The concepts of career anchors and internal career orientations partly overlap and complement each other. This offers the potential for integrating these concepts into core career aspirations (see Table 1, first column). The first four core career aspirations are combinations from both concepts. Freedom subsumes the career anchor Autonomy and Independence and the orientation Getting Free. It stands for autonomy, self-control and personal freedom, particularly from organizational constraints. It is important to have space and responsibility, one's own schedule and work pace under loose supervision. Security includes Security/Stability and Getting Secure. It subsumes the desire for long-term job security and attachment to one organization where it is possible to achieve a sense of identity, order and place in conformity with organizational values and norms. “Security seekers tend to dislike travel and relocation” (Schein, 1990 cited in Suutari & Taka, 2004: 836). Balance covers Lifestyle and Getting Balanced. It includes the desire for balancing the three forces of the career triangle, i.e. work, relationships, and self-development. People with this aspiration tend to look for organizations with strong pro-family values and programs. The aspiration Management and Hierarchy comprises General Managerial Competence and Getting Ahead. It underlines the need for hierarchical advancement and leadership positions to obtain more influence, status, and financial remuneration. Its most important skills are interpersonal and analytical competencies as well as emotional stability.

The other six core career aspirations are directly based on the two respective. Getting High refers to an “adrenaline-first strategy” focusing on excitement, action, adventure, and creativity. People try to avoid boredom and routine and view bureaucratic rules as constraints. Pure Challenge emphasizes competition and challenges. Winning is important, as is overcoming major obstacles and solving the insoluble. Entrepreneurial Creativity emphasizes creating something that is entirely one's own project. People with this aspiration are easily bored, they like to initiate new things rather than managing established ones and they move from project to project. Service or Dedication to a Cause focuses on improving the world. Technical-functional Competence refers to people who are motivated by the work content. They want to become deep experts in their field and thus seek advancement only in their own technical or functional area of competence. Finally, Internationalism focuses on people who seek working in international environments, who long for new experiences in different countries and cultures in order to enhance their competencies and career opportunities.

Prior research and main research questions as points of departureOpenness to the subject matter is one of the principles of qualitative research and has also been applied to this paper. Of course, this does not preclude formulating a point of departure based on the current state of research. Two major questions constitute our starting point.

Career anchors were first looked at in the 1970s. Schein (1996) observed shifts in his findings in the 1990s and his framework has been further extended for specific professional and country samples (e.g., Ituma & Simpson, 2007; Suutari & Taka, 2004). In today's turbulent, fast-paced world, career anchors have become more significant to individuals and shifts in their structure and content can be expected (Schein, 1996). Furthermore, when examining career anchor and internal career orientation concepts in light of the prominent research topics in international business and career studies, certain items seem to be missing, for example the role of relational aspects such as (developmental) networks in careers and career success (e.g., Ibarra & Deshpande, 2007). Against this backdrop, our first major question revolves around the adequacy of existing career aspiration frameworks and whether the specifics of the current economic and political environment in Europe as well as of flexpatriation as a meanwhile established form of working internationally lead to additional new career aspirations.

Empirical insight into flexpatriation is rather scarce compared to the body of research related to expatriation (Welch et al., 2007). Yet, some evidence for characteristics of this form of international work exists, and they may give some indications on potential career aspirations too. Perceived positive aspects of flexpatriation mentioned include variety and novelty, excitement, lifestyle, personal development, personal contacts and networks as well as respite and relaxation from everyday life. Perceived negative factors comprise family separation, travel stress, health issues, safety concerns, incessant work demands and work role conflicts (e.g., DeFrank, Konopaske, & Ivancevich, 2000; Welch & Worm, 2006; Welch et al., 2007). Hence in our study we may expect career aspirations of flexpatriates to particularly evolve around subjective aspects like personal experience and development or variety and change.

Beyond that, there is some evidence for specific career anchors for expatriates. They include Internationalism, Pure Challenge, Lifestyle, and General Managerial Competence (Cerdin & Pargneux, 2010; Suutari & Taka, 2004). In particular, the centrality of Lifestyle/Getting Balanced (e.g., Derr & Laurent, 1989; Schein, 1996) and the difficulties of expatriates in their work-life balance have been pointed out (e.g., Challiol & Karim, 2005; Harvey, 1997). Related to the German language area, Stahl and Cerdin (2004) find that for German expatriates Pure Challenge is the most important reason for accepting an international assignment. Due to the cultural closeness of our sample (e.g., Schwartz, 2006), we expect a similar picture for Austrian individuals. Additionally, expectations and motives for expatriate assignments studied may give some further insights into expatriates’ aspirations. Prior literature (e.g., Dickmann, Doherty, Mills, & Brewster, 2008; Kühlmann, 2004; Stahl et al., 2002) highlights career advancement, increase in responsibility, tasks and status as main motives of accepting international assignments. Hence, we may assume the aspiration of Management and Hierarchy to be central to our expatriate sample as well.

Our literature review leads to our second major question. It focuses on which typical career aspirations of IMEs emerge and which ones appear to be specific to flexpatriates compared to expatriates.

Sample and methodsA qualitative research methodology was adopted for the purposes of description, interpretation, and explanation. Qualitative approaches have proven especially valuable to grasp meanings and interpretations of individuals’ views of reality. Contextualization as well as openness and search for meaning are central criteria (Marschan-Piekkari & Welch, 2005; Miles & Huberman, 1994). To qualitative research – including our study – particular, unique and individual cases are in focus, especially in not well- or even unknown research areas (Heinze, 2001). Central aims are theory or hypothesis generation, classifications, or the conduction of pilot studies and in depth analyses (Mayring, 2003).

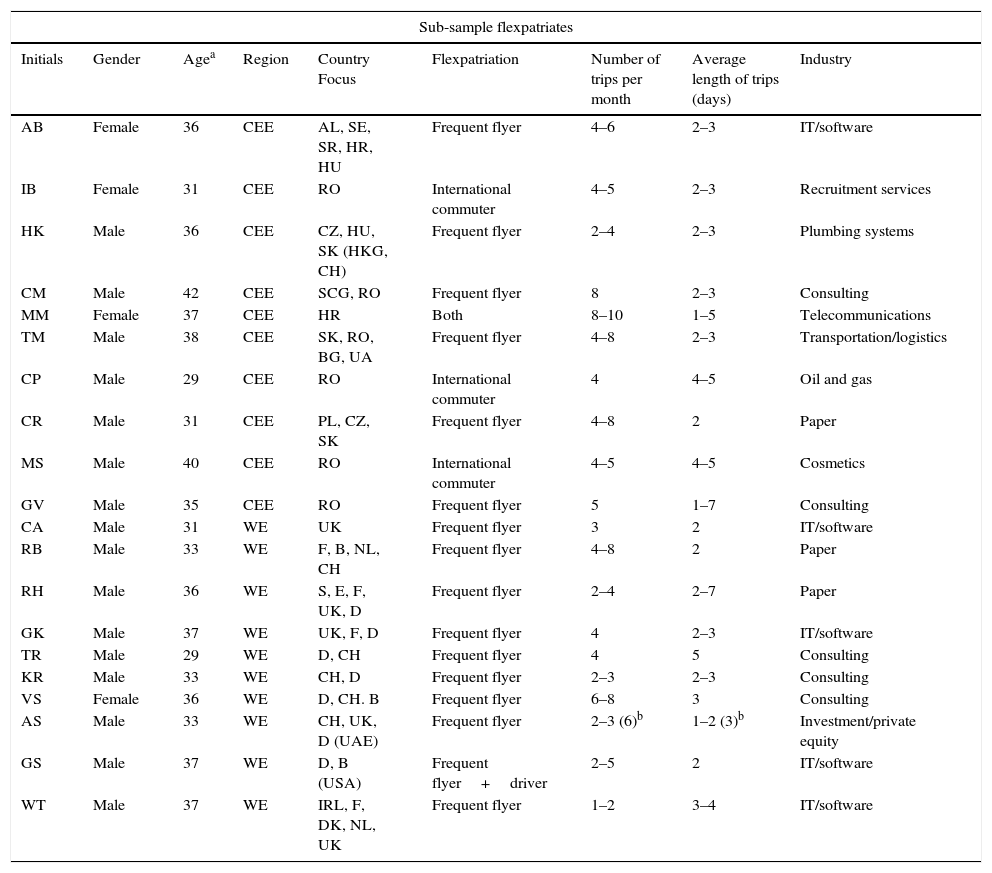

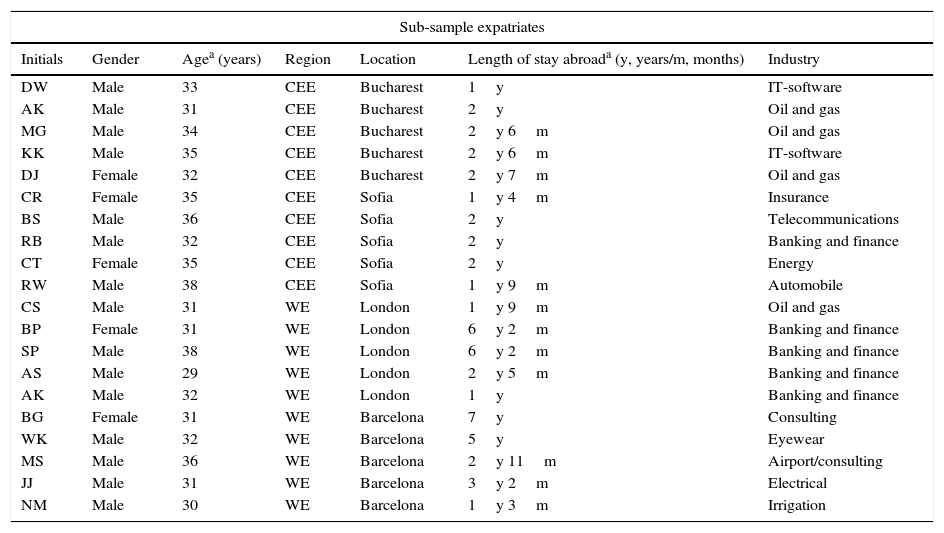

SampleThe IMEs in our sample consist of 40 Austrian managers (20 flexpatriates and expatriates each) working in Eastern and Western European countries, particularly Romania and Bulgaria and the UK and Spain, respectively. On average, the flexpatriates (16 males, 4 females) travel abroad five times a month with an average duration of three days per trip. The expatriates (15 males, 5 females) have relocated abroad and lived there for at least a year with an average time abroad of 2.8 years at the time of data collection. To support comparison, we kept our subsamples as homogenous as possible in terms of age (average 34 years), region, having a managerial position in a private company, holding the current job for at least a year, and being partners in dual-career couples where both partners are employed. Sex distribution of individuals – 20% women – corresponds with the present realities of expatriation (e.g., Brookfield Global Relocation Services, 2012). We approached and selected most of our interviewees from the IME group via Austrian embassies abroad, chambers of commerce, expatriate clubs, and Xing, an online platform for business networking. Tables 2a and 2b provide more detailed information on the sample.

Sample description.

| Sub-sample flexpatriates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initials | Gender | Agea | Region | Country Focus | Flexpatriation | Number of trips per month | Average length of trips (days) | Industry |

| AB | Female | 36 | CEE | AL, SE, SR, HR, HU | Frequent flyer | 4–6 | 2–3 | IT/software |

| IB | Female | 31 | CEE | RO | International commuter | 4–5 | 2–3 | Recruitment services |

| HK | Male | 36 | CEE | CZ, HU, SK (HKG, CH) | Frequent flyer | 2–4 | 2–3 | Plumbing systems |

| CM | Male | 42 | CEE | SCG, RO | Frequent flyer | 8 | 2–3 | Consulting |

| MM | Female | 37 | CEE | HR | Both | 8–10 | 1–5 | Telecommunications |

| TM | Male | 38 | CEE | SK, RO, BG, UA | Frequent flyer | 4–8 | 2–3 | Transportation/logistics |

| CP | Male | 29 | CEE | RO | International commuter | 4 | 4–5 | Oil and gas |

| CR | Male | 31 | CEE | PL, CZ, SK | Frequent flyer | 4–8 | 2 | Paper |

| MS | Male | 40 | CEE | RO | International commuter | 4–5 | 4–5 | Cosmetics |

| GV | Male | 35 | CEE | RO | Frequent flyer | 5 | 1–7 | Consulting |

| CA | Male | 31 | WE | UK | Frequent flyer | 3 | 2 | IT/software |

| RB | Male | 33 | WE | F, B, NL, CH | Frequent flyer | 4–8 | 2 | Paper |

| RH | Male | 36 | WE | S, E, F, UK, D | Frequent flyer | 2–4 | 2–7 | Paper |

| GK | Male | 37 | WE | UK, F, D | Frequent flyer | 4 | 2–3 | IT/software |

| TR | Male | 29 | WE | D, CH | Frequent flyer | 4 | 5 | Consulting |

| KR | Male | 33 | WE | CH, D | Frequent flyer | 2–3 | 2–3 | Consulting |

| VS | Female | 36 | WE | D, CH. B | Frequent flyer | 6–8 | 3 | Consulting |

| AS | Male | 33 | WE | CH, UK, D (UAE) | Frequent flyer | 2–3 (6)b | 1–2 (3)b | Investment/private equity |

| GS | Male | 37 | WE | D, B (USA) | Frequent flyer+driver | 2–5 | 2 | IT/software |

| WT | Male | 37 | WE | IRL, F, DK, NL, UK | Frequent flyer | 1–2 | 3–4 | IT/software |

CEE, Central and Eastern Europe; WE, Western Europe.

Sample description.

| Sub-sample expatriates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initials | Gender | Agea (years) | Region | Location | Length of stay abroada (y, years/m, months) | Industry |

| DW | Male | 33 | CEE | Bucharest | 1y | IT-software |

| AK | Male | 31 | CEE | Bucharest | 2y | Oil and gas |

| MG | Male | 34 | CEE | Bucharest | 2y 6m | Oil and gas |

| KK | Male | 35 | CEE | Bucharest | 2y 6m | IT-software |

| DJ | Female | 32 | CEE | Bucharest | 2y 7m | Oil and gas |

| CR | Female | 35 | CEE | Sofia | 1y 4m | Insurance |

| BS | Male | 36 | CEE | Sofia | 2y | Telecommunications |

| RB | Male | 32 | CEE | Sofia | 2y | Banking and finance |

| CT | Female | 35 | CEE | Sofia | 2y | Energy |

| RW | Male | 38 | CEE | Sofia | 1y 9m | Automobile |

| CS | Male | 31 | WE | London | 1y 9m | Oil and gas |

| BP | Female | 31 | WE | London | 6y 2m | Banking and finance |

| SP | Male | 38 | WE | London | 6y 2m | Banking and finance |

| AS | Male | 29 | WE | London | 2y 5m | Banking and finance |

| AK | Male | 32 | WE | London | 1y | Banking and finance |

| BG | Female | 31 | WE | Barcelona | 7y | Consulting |

| WK | Male | 32 | WE | Barcelona | 5y | Eyewear |

| MS | Male | 36 | WE | Barcelona | 2y 11m | Airport/consulting |

| JJ | Male | 31 | WE | Barcelona | 3y 2m | Electrical |

| NM | Male | 30 | WE | Barcelona | 1y 3m | Irrigation |

CEE, Central and Eastern Europe; WE, Western Europe.

To ensure the consistency required in comparative analyses (Bortz & Döring, 2002), data were gathered through semi-structured face-to-face interviews conducted in German by the first author. The qualitative measurement of career anchors and internal career orientations includes questions on career choice and underlying motives and goals (see Schein, 1990) as well as conceptualizations of career success (following Derr & Laurent, 1989). Additional questions relevant to this paper address career aspirations as well as short- and long-term career and career success descriptions.

Examples for questions closely linked to career aspirations/career success orientations include: “What does career success mean, what is your understanding of career success?“, “How would you measure career success, what parameters would show that you are successful in your career?”, “Could you describe what you aspire to in your career?”, “Could you describe where you see yourself in your career in about 2–3 years’ time? And in 8–10 years?”, “What needs to happen in 8–10 years that you would (still) say – ‘I am successful’?”, “What are your objectives behind choosing a job as flexpatriate”.

One pre-test interview was conducted to ascertain the quality of data collection. On average the interviews lasted 50min. They were digitally recorded and fully transcribed.

Data analysis applied a variant of qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2003). This provides an inductive, step-by-step procedure to extract core categories from individuals’ responses. To obtain a refined set of core and sub-categories reflecting the original content of interview data we followed both Mayring's (2003) elaboration process and a constant comparative method (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Such a system of categories enhances comparability and intersubjective traceability (Mayring, 2003). To assure a high degree of intra-coder reliability main parts of the interviews were coded again after a couple of months; the final system of categories was rechecked with half of the interviews. Inter-coder reliability (e.g., Krippendorff, 2004) was also evaluated. By comparing the original coding of the first author with the coding of a second rater, the agreement coefficient (Holsti, 1969) amounts to 0.81, which is satisfactory (Krippendorff, 2004). Coding and analysis were supported by the software NVivo 7.0. In order to detect additional commonalities and differences among the subsamples, we followed recommendations for simple quantitative analysis in a qualitative study, e.g., to reveal the dispersion of central themes (e.g., Bühler-Niederberger, 1991; Mayring, 2003). They further support the picture emerging from the content analysis.

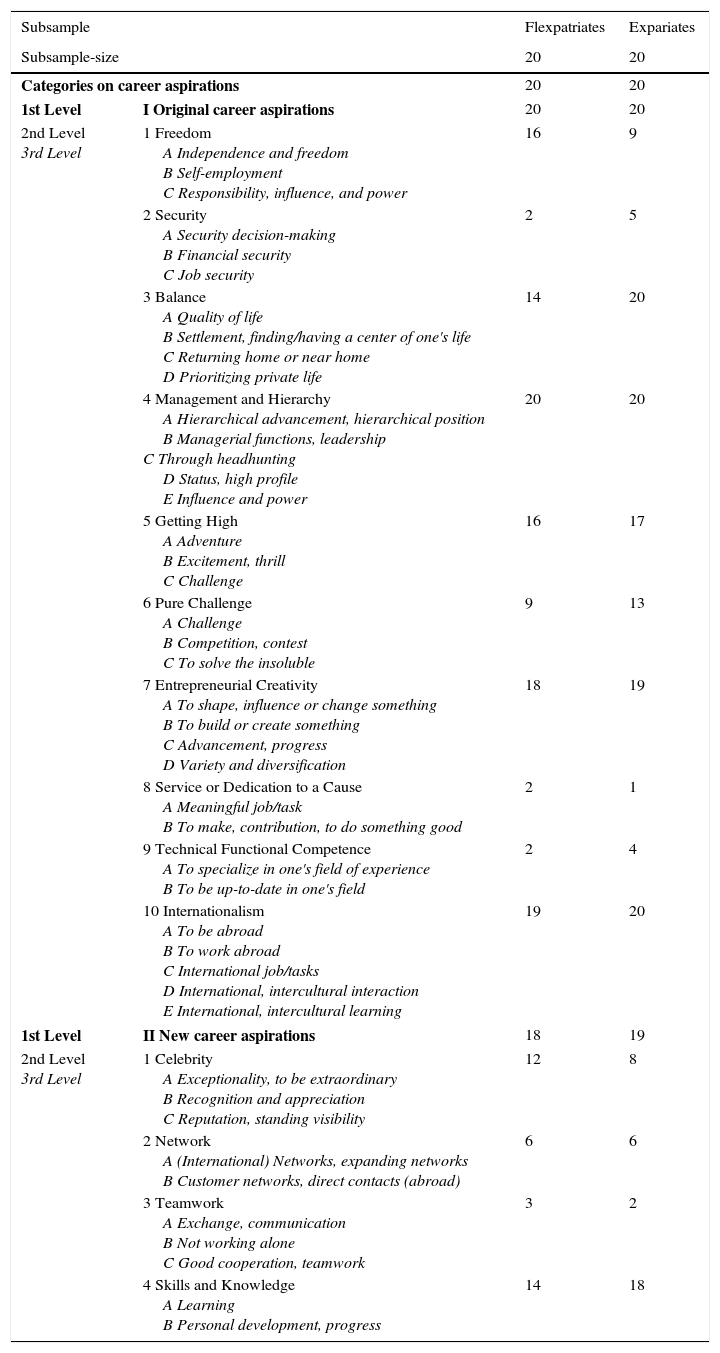

Detailed coding processIn a first step, we inductively extracted categories and sub-categories from our data. In a second step we classified the emerging categories according to the 10 integrated career anchors and internal career orientations that already exist in the theoretical frameworks used. Checking back and forth the categories and corresponding interview passages with the detailed explanations on existing frameworks, we found that not all of the emerging categories fit the existing career aspirations in literature. Therefore, in a third step, we created new, additional categories for career aspirations (see Table 3 and descriptions below).

Comparing core career aspirations of flexpatriates and expatriates.

| Subsample | Flexpatriates | Expariates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subsample-size | 20 | 20 | |

| Categories on career aspirations | 20 | 20 | |

| 1st Level | I Original career aspirations | 20 | 20 |

| 2nd Level 3rd Level | 1 Freedom A Independence and freedom B Self-employment C Responsibility, influence, and power | 16 | 9 |

| 2 Security A Security decision-making B Financial security C Job security | 2 | 5 | |

| 3 Balance A Quality of life B Settlement, finding/having a center of one's life C Returning home or near home D Prioritizing private life | 14 | 20 | |

| 4 Management and Hierarchy A Hierarchical advancement, hierarchical position B Managerial functions, leadership C Through headhunting D Status, high profile E Influence and power | 20 | 20 | |

| 5 Getting High A Adventure B Excitement, thrill C Challenge | 16 | 17 | |

| 6 Pure Challenge A Challenge B Competition, contest C To solve the insoluble | 9 | 13 | |

| 7 Entrepreneurial Creativity A To shape, influence or change something B To build or create something C Advancement, progress D Variety and diversification | 18 | 19 | |

| 8 Service or Dedication to a Cause A Meaningful job/task B To make, contribution, to do something good | 2 | 1 | |

| 9 Technical Functional Competence A To specialize in one's field of experience B To be up-to-date in one's field | 2 | 4 | |

| 10 Internationalism A To be abroad B To work abroad C International job/tasks D International, intercultural interaction E International, intercultural learning | 19 | 20 | |

| 1st Level | II New career aspirations | 18 | 19 |

| 2nd Level 3rd Level | 1 Celebrity A Exceptionality, to be extraordinary B Recognition and appreciation C Reputation, standing visibility | 12 | 8 |

| 2 Network A (International) Networks, expanding networks B Customer networks, direct contacts (abroad) | 6 | 6 | |

| 3 Teamwork A Exchange, communication B Not working alone C Good cooperation, teamwork | 3 | 2 | |

| 4 Skills and Knowledge A Learning B Personal development, progress | 14 | 18 | |

Note: The figures indicate the number of people mentioning the respective categories at least once. The numbers do not serve a quantitative analysis purpose but merely give support and guidance for our qualitative content analysis. Source: Demel (2010): 237.

Table 3 presents the career aspirations elaborated from our interview data.

Career aspirations revealed by the data as well as literatureWe found all 10 existing categories in our inductive analysis. The data supports the descriptions in the theoretical frameworks used. Below is a summary of the man ideas behind these categories found in our interviews:

Freedom particularly expresses the need for independence, i.e. freedom in decision-making and flexibility concerning scope of tasks and work procedures, which is also linked to self-employment and requires certain knowledge and development. Security subsumes above all financial and job security, also working for a solid company and following secure decisions. Balance refers above all to quality of life, e.g., finding time to relax, having less stress and strains, settlement, i.e. finding an actual center in one's life, returning home or near home, prioritizing private life, work life balance and wellbeing. Management and Hierarchy covers above all aspirations like hierarchical advancement, acquiring certain managerial positions, status, gaining responsibility, money and assets. Getting High particularly refers to adventure and excitement, challenging, interesting and diversified tasks or activities. Pure Challenge of course also covers challenges and it is especially about outplaying competitors and solving the insoluble. Entrepreneurial Creativity has above all to do with influencing and shaping something, with creating something new, with progress, job variation, including self-employment. Service or Dedication to a Cause comprises aspirations like making a contribution, doing a meaningful job or making a difference for society. Technical-functional Competence above all refers to being an expert, to technical specialization and advancement in one's professional area of expertise, and to be up-to-date in one's field. Internationalism covers the aim of being or traveling abroad, seeking international jobs and intercultural interaction, learning from international experience and expanding one's network internationally.

New career aspirations beyond existing conceptsOur detailed analysis revealed four new, additional categories for career aspirations: Celebrity, Network, Teamwork, and Skills and Knowledge. In line with the basic conceptualization, all four categories are linked to individuals’ talents and abilities, values, motives, and needs.

Celebrity reflects the desire to be exceptional and do something extraordinary. Important components are recognition and appreciation by one's environment, reputation, and visibility. In contrast to Management and Hierarchy and Pure Challenge, this category is not about hierarchical advancement and competition but rather being recognized as somebody special and contributing to something big: “It needs to be something extraordinary that I am doing, I am not satisfied with average; I know I demand a great deal but once I meet these demands I am extremely satisfied.” [CA, Flex (31, m)1]

Celebrity is more closely linked to dimensions of subjective career success (Heslin, 2005) than Management and Hierarchy for example.

Network subsumes the aim of building and expanding one's networks, preferably internationally. Direct contact with one's clients (abroad) and establishing an extensive customer network with access to distinct markets are important. “My goal has always been to come here [to London], gain experience, learn, and establish the right contacts and networks which eases your career a lot in the longer run.” [AS, Exp (29, m)]

Teamwork encompasses the need to exchange thoughts and communicate with others, specifically in a team. People dislike working alone and prefer good cooperation and teamwork with peers and superiors: “I don’t like working alone, I am a team player. What disturbed me most when I was working as a consultant was to be alone, without a team.” [MM, Flex (37, f)]

Skills and Knowledge is based on the desire for constant learning and development as well as personal advancement and progress. The category reflects the wish to continuously become better at what one is doing, to learn on the job, broaden one's horizon, and develop professionally. In contrast to Technical-functional Competence this category is more about lifelong learning, less technical-oriented and again resembling more subjective dimensions of career success (Nicholson and de Waal-Andrews, 2005). “What definitely is an important factor for me is the longing to always become and do things better and better. Actually that really drives me.” [WK, Exp (32, m)]

First, we analyzed which of the career aspirations were most prominent in our flexpatriate sample. Five career aspirations emerged: Management and Hierarchy, with a focus on hierarchical advancement, money and assets; Internationalism, with an emphasis on traveling, international/intercultural learning and working abroad; Entrepreneurial Creativity, underlining variety and diversification, self-employment as well as the desire to shape, influence or change something; Getting High, with a focus on variety and diversification, challenge and excitement; and Freedom, highlighting the value of independence, freedom and self-employment. Least important to flexpatriates, though still mentioned, are Security, Service or Dedication to a Cause, and Technical-functional Competence.

Almost every flexpatriate aspires to hierarchical advancement and achieving a certain managerial level within an organizational hierarchy (Management and Hierarchy). “In about two to three years, maybe a bit longer, I want to become a member of the board.” [AB, Flex (36, f)] “Still I would like to become CEO of a big company.” [VS, Flex (36, w)] “I will either lead the whole company or … or I will become a shepherd!” [CM, Flex (42, m)]

Furthermore, the desire to travel is characteristic to flexpatriates (Internationalism): “… To me travelling is something inspiring, something I feel very positive about and which I do not perceive as a strain because I enjoy dealing with different people, seeing different cultures, talking different languages; that is actually the main reason for me why I started doing this job which involves a lot of travelling.” [CA, Flex (31, m)]

In addition job variation, to shape, influence or change something as well as excitement at work are important (Entrepreneurial Creativity and Getting High): “What is extremely important to me is having an influence on things, to be able to create something, to build something, and to have an impact.” [AS, Flex (33, m)] “Well, I don’t hate anything more than … I mean it would be a really horrifying scenario to imagine a nine-to-five job in some government agency. I would not be able to bear that!” [GV, Flex (35, m)] “After 12 to 18 months I always start thinking ‘ok, well we’re actually finished now, what's next?’ And each time I have been offered a new challenge…” [MM, Flex CEE (37, w)] “Because to me there is nothing bigger than to do what you like and what you enjoy” [AB, Flex (36, w)]

To have a certain autonomy and independence, including a sense of self-monitoring, is also vital when it comes to career aspirations of flexpatriates: “That means that you do something you are able to do when you feel like doing it. You won’t do it if you don’t want to and you have enough money which gives you the freedom of not having to do it at all.” [AB, Flex (36, w)] “My ideal scenario in 8–10 years would be that I will have enough money that I do not have to go to work anymore.” [GK, Flex (37, m)]

Subsequently, we analyzed whether some aspects were unique to flexpatriates when compared to the expatriates of our sample.

Starting with commonalities, both flexpatriates and expatriates underline three aspirations in a very similar way: Management and Hierarchy, with a focus on hierarchical advancement, money, and assets, Internationalism, with an emphasis on traveling, international/intercultural learning, working abroad and inspiration from one's internationality. Third, Entrepreneurial Creativity, underlining variety and diversification as well as the desire to shape, influence or change something. “Well, yes, a clear goal of mine is to reach Board Level. Yes actually, in about 2 years’ time I would like to advance to Board Level.” [RW, Exp (38, m), Management and Hierarchy] “Because I personally hate nothing more than making an effort for nothing, when personal investment does not lead to any contribution.” [DW, Exp (33, m), Entrepreneurial Creativity] “Austria is not at all interesting to us at the moment, job-wise, and it would be exciting to me to go somewhere else afterwards” [DJ, Exp (32, w), Internationalism] “You look outside the box and that is incredibly important, I would love to work in every country of the world [laughing], just to see how everything works differently, … yes, at least to work on each continent once, I would really like that, but we’ll see.” [MG, Exp (34, m), Internationalism]

Similarly mentioned by both subsamples is the aspiration of Getting High. Both flex- and expatriates stress the need for variety and diversification in their work, i.e. doing new, distinct tasks and avoiding routine jobs. While to flexpatriates excitement and thrill are important, expatriates talk more about adventures and challenges, which is also why they emphasize Pure Challenge more than flexpatriates. “I seek something new … well, I am somebody who likes adventures … ahm, after being in a job for about 2 years I usually tend to get a bit bored you know…” [DW, Exp (33, m)] “I want to be challenged and I think that in a couple of years financial incentives will no longer be that important, but to have challenges is and will be essential.” [KK, Exp (35, m)] “I have to feel challenged, and I also have to challenge myself.” [RB, Exp CEE (32, m)]

Main differences are observed for Freedom, underlined more by flexpatriates, with particular emphasis on doing what they want to and enjoying it, and Balance, mentioned a lot more by expatriates, with an emphasis on the desire to return home or near home and giving priority to one's private life: “I want personal freedom at work, which means that I can choose what I do myself and if and when I’d like to do it. […] I value nothing more than being able to do what I want and enjoying it, and to still be able to make a living from it.” [AB, Flex (36, f), Freedom] “Well, my second assignment, … I wouldn’t have done it if my wife didn’t have the possibility to get a job there too and come with me.” [RB, Exp (32, m), Balance] “That was the absolutely decisive factor [for returning home], because my wife moved back. If she had stayed I would have probably prolonged for another year.” [BS, Exp (36, m), Balance] “If we want to maintain our relationship in the future, we sooner or later have to find a place for both of us, either she will come with me to Austria or I will stay in Spain or we will even find a third location for us …” [JJ, Exp (31, m)]

A further difference is observed for Skills and Knowledge, less important to flexpatriates compared to expatriates. Vital topics are development, progress and learning something new and distinct. “To personally develop in the long run is definitely important, too. In my past few years as sales manager I primarily wanted to learn, and my desire to learn has really helped me a lot.” [WK, Exp (32, m)]

Celebrity by contrast is mentioned more by flexpatriates, who stress the need for recognition and appreciation. “… Recognition, everybody wants recognition, it's about earning appreciation, otherwise you wouldn’t do it; you don’t do it only for yourself.” [CM, Flex (42, m)]

Particular to flexpatriates remain aspects concerning Freedom; also Celebrity is most important to flexpatriates. Expatriates on the other hand underline Skills and Knowledge most as well as Pure Challenge.

DiscussionWe started this paper with asking to what extent the career aspirations of flexpatriates in the European context are different from the quite well-researched aspirations of ‘classical’ expatriates. Before reflecting on this core question, we will also briefly discuss two related questions addressed in this study: are there new career aspirations emerging in the international arena which are absent from traditional orientations implicitly focusing on a more national environment and what emphases do internationally mobile employees show in their career aspirations? We will deal with these theoretical contributions in turn.

Theoretical contributionsNew career aspirationsOur findings reveal, indeed, four new career aspirations. Celebrity is important to people who long to be special and do something exceptional in order to earn feedback and appreciation. Network is based on the desire to increase one's network and contacts, thus enhancing one's business and career opportunities. Teamwork is stressed by people who dislike working alone and need interaction with others. It not only meets social needs, but also reflects the ability and willingness to work well in teams. Skills and Knowledge calls for constant learning and broad development in various areas.

This not only positively answers our first research question, but also raises a number of further considerations. Looking at the four new categories, they hardly are limited to the realm of international work. On the contrary, they seem to echo more fundamental developments in the world of work. They revolve around new cohorts/generations of individuals entering the labor market who have a different understanding of the give-and-take-relationship between organizations and their employees (e.g., Mayrhofer, Nordhaug, & Obeso, 2011); around an increasingly interconnected world of work where different types of networks both at the organizational and the individual level as well as working in teams has reached a new degree of importance (e.g., Dobrow, Chandler, Murphy, & Kram, 2012); and around the fact that the creation and management of knowledge has become a new and, arguably, crucial success factor for both individuals, organization and society (e.g., Pucik, Björkman, Evans, & Stahl, 2015). If one subscribes to such a view, this leads, among others, to a number of consequences in the realm of conceptualizing tertiary education and organizational HRM. Curricula at universities and other educational institutions as well as personnel and leadership development programs might be checked against the suggested incentive structures, degree of collaborative skills that are explicit part of the programs, or meta-competencies allowing individuals and organizations to deal with explicit and tacit knowledge. For HRM, the ‘celebrity aspiration’ also raises issues in terms of realistic recruitment, employer branding and onboarding programs in order to be attractive for well-qualified members of the work force while, at the same time, provide a realistic preview of what is possible in current day organizations dealing facing tight competition and cost pressures.

Specifics of internationally mobile employees (IMEs)With regard to the aspirational emphases of internationally mobile employees, our results underline Internationalism and Getting High as aspirations specific to IMEs. Consistent with prior findings (e.g., Suutari & Taka, 2004; Welch & Worm, 2006) we find that Internationalism is crucial, specific to both subsamples and concurs with the trend that careers are becoming increasingly international or global (e.g., Peiperl & Jonsen, 2007). Getting High, underscoring routine avoidance, is not surprising for IMEs and mentioned in prior research findings (DeFrank et al., 2000; Stahl & Cerdin, 2004; Welch & Worm, 2006). In addition, the focus on Management and Hierarchy as well as Entrepreneurial Creativity seem to have significance beyond IMEs.

Although Management and Hierarchy has previously been emphasized (e.g., Stahl & Cerdin, 2004; Suutari & Taka, 2004), its prominence in our subsamples is striking. For flexpatriates a possible explanation could be the desire to compensate for the stress and strain of their jobs (e.g., DeFrank et al., 2000) with hierarchical advancement. Promotions and benefits may also counterbalance the lack of organizational support and management of flexpatriates (e.g., Welch et al., 2007). Concerning expatriates, this result might reflect their quite strong integration in organizational systems, cultures and hierarchies, at least during the time of their assignment. This is consistent with main organizational objectives behind expatriate assignments such as skill transfer, management development, and managerial control. Moreover, the cultural background may suggest an emphasis on these rather objective career elements too: An international study on careers across cultures shows that financial and hierarchical achievement are central dimensions of career success in Austria (Demel et al., 2009). The emphasis on Entrepreneurial Creativity, i.e. the need for variety and diversification, the desire to shape, influence or change something as well as to be self-employed, is remarkable, too. While critical voices (e.g., Inkson, Gunz, Ganesh, & Roper, 2012) have challenged the overall emergence of “protean” (Hall, 1996) and “boundaryless” (Arthur, 1994) careers resembling these characteristics, the international career arena might constitute a fitting context for pro-active, entrepreneurial selves being less dependent on organizational boundaries and in search of self-agency and subjective growth.

These findings not only shed light on one of our research questions, but also raise at least two further issues. On the one hand, our results call for further research into the specifics of internationally mobile employees in the area of careers and career aspirations. While the extant research on expatriation and, growing in volume, new forms of working abroad already have generated a substantial body of knowledge, we still need a more refined understanding about various aspects of IMEs’ careers. They include, e.g., the process of when and how specific career aspirations develop, are sustained and changed; the role of mentors, role models, in particular other IMEs, and organizational HRM practices in developing and sustaining these career aspirations; or how these aspirations and their relative salience change over time depending on the experiences the IMEs make abroad. On the other hand, our findings also point out that IMEs are not solely ‘special’, but also ‘normal’ employees. This indicates a partly neglected area in research on IMEs: their relationship to non-IMEs and their integration into the standard operating procedures of the organization. Questions that arise not only focus on repatriation as a traditional field of research, but also on the consequences of organizations treating foreign assignments as part of a standard work assignment with no special packages or the extent to which effects of working internationally also apply to domestic jobs with a high proportion of ‘virtual international work’ through joint projects, video-conferences, etc.

Specifics of flexpatriatesAnswering our core question, our results show a number of particularities of flexpatriates. In comparison to expatriates, they put a greater emphasis on the following aspirations. Underscoring Freedom by seeking autonomy and self-employment coincides with the values stressed in the “protean career” concept (e.g., Hall, 2004), where freedom, growth and independence from organizational structures allowing self-control over one's career according to one's own values and needs is essential. Considering that flexpatriates’ organizational roles are vaguely defined (e.g., DeFrank et al., 2000) and they are not well supported in their organizations despite work pressures and travel stress (e.g., Mayerhofer et al., 2004), this is hardly surprising. They want – and need – to define their position themselves and control their work and travel rhythms. Similar results are found for Celebrity. A major explanation for this is their ill-defined role and lack of support. Furthermore flexpatriates, who often work in several countries, are not as socially affiliated as colleagues who travel less. Hence they may have difficulties finding their own identity. Flexpatriates enjoy their lifestyle (e.g., Welch & Worm, 2006) which makes them feel important and glamorous and holds recognition. All this increases the importance of recognition and appreciation.

Vice versa, three aspirations seem to be of lesser importance. Balance, i.e. the desire to balance one's work and personal life, is mentioned, but does not appear as a vital aspiration. This is consistent with Schein's (1996) predictions as well as other empirical findings (e.g., Carlson, Derr, & Wadsworth, 2003; Suutari & Taka, 2004) It seems that flexpatriates are mainly driven by self- and work-centered aspirations, e.g., their longing for hierarchical advancement, freedom, travel, and variety in tasks and environments. One explanation is that accepting a job requiring international travel, flexibility and spontaneity can hardly be coupled with a strong desire for a work-life balance since it would cause cognitive dissonance. Hence, one or the other has to become lower in priority. Moreover, our subsample seems to include flexpatriates with two distinct mindsets: On the one hand, flexpatriates highly value their home life. They fly as frequently or commute as regularly as possible to avoid relocation and the disruption of relationships with their partner and friends. Flexpatriates with that mindset might perceive work-nonwork conflicts more strongly. On the other hand, Demel (2010) shows that many flexpatriates appreciate a certain distance from their partners during the week since more time and concentration can be dedicated to work. They view few days or weekends as sufficient time for their private life. To them everyday life in relationships seems less important and they enjoy the honeymoon spirit of longer-distance relationships. Skills and Knowledge appears more important to expatriates. It seems that internal career considerations like professional development and learning opportunities have become increasingly important to expatriates (Stahl & Cerdin, 2004; Stahl et al., 2002; Tung, 1998). Considering repatriates’ difficulties in career advancement within the same company (Doherty, Brewster, Suutari, & Dickmann, 2008), this aspiration makes expatriates less dependent on their company and open to a more “boundaryless” concept of career (e.g., Stahl et al., 2002). Finally, flexpatriates also talk less than expatriates about Pure Challenge, although literature would have suggested it otherwise (e.g., Stahl & Cerdin, 2004; Welch & Worm, 2006). Possibly, they perceive excitement and challenge already incorporated in Internationalism, hence not stressing it specifically. Our findings for expatriates concur with prior research on German expatriates which found challenges as the most important reason for accepting an international assignment (Stahl & Cerdin, 2004).

These results seem to justify additional research into the role of flexpatriates. While expatriates have been researched extensively, we still know comparatively little about flexpatriates. The specifics mentioned above seem to demonstrate that this is a group of its own within the larger setting of internationally mobile employees. They lack the rhythm of typical everyday working lives which after some time of adjustment is true for many expatriates and they are often not covered by the HRM routines that organizations have developed for dealing with expatriates.

Further research implicationsBeyond the consequences outlined above, our analysis has a number of additional implications. First, it suggests the integrated use of the career anchor and internal career orientation frameworks as well as the consideration of four additional categories. The key findings also show a mix of rather traditional aspirations like Management and Hierarchy or Balance and categories that have not been prominent in previous studies, i.e. Entrepreneurial Creativity, Getting High or Freedom. In addition, important aspirations to flex- and expatriates resemble characteristics of “new careers” (e.g., Arthur, 1994; Hall, 1996). While these concepts face substantial critique, our findings indicate IMEs in Europe to be pro-active, independent selves. However, this assumption cannot be based on career aspirations only and more research is needed looking at concepts like habitus, identity, mindset or personality factors. Additionally, our sample does not allow controlling for life stage or different forms of (non-)partnership. We also suggest looking at changes in career aspirations of flex- and expatriates over time.

Second, our paper contributes to the discussion on contextualizing HRM and careers in Europe. While most prior research was conducted in the North-American context, this study gives insight into individuals working in Eastern and Western European countries. It would be interesting to see similar research efforts in other regions of the world to get a better understanding of the role of cultural and institutional contexts for career aspirations.

Third, while our research suggests the emergence of additional core career aspirations, these findings are clearly preliminary. A broader sample is needed to confirm and refine these results. In this way, future research could contribute to the theoretical development of the field. These efforts could also give further insights into comparisons of career aspects of an international versus domestic workforce.

Practical relevanceFirst, management positions and hierarchical advancement have a high importance for both flex- and expatriates. This requires careful career management for individuals returning as well as staying or frequently flying abroad. At least within a realistic scope and time frame, career paths have to be planned and integrated into business strategies; otherwise employees will search for more adequate positions elsewhere.

Second, the high importance of Entrepreneurial Creativity underlines the significance of tailored career management measures, too. Among other options, self-employment seems to be a good alternative for flex- and expatriates if a company fails to meet their expectations. Hence, if companies want to keep valuable employees and their knowledge, they have to plan positions within the organization or establish alternative ways of cooperation, e.g., with former flexpatriates offering their know-how as self-employed consultants.

Third – and specifically concerning flexpatriates – our results indicate that it is essential for HRM to provide adequate legal and psychological contracts for flexpatriates – who do not yet have fully defined roles (e.g., Harris, Brewster, & Erten, 2005) – which give them recognition and specify their role, responsibilities and travel rhythms. At the same time HRM has to consider the strong need of flexpatriates for autonomy and independence. Awareness of important drivers as well as central tasks that may suit their aspirations best can strongly support decision-making in recruiting or succession planning. Integrating knowledge about aspirations of IMEs in general may also prevent high turnover rates like those which characterize expatriates (e.g., Dowling, Festing, & Engle, 2008).

Limitations and suggestions for future studiesWhen discussing our findings, we acknowledge some limitations. First, although the sample size is adequate for an exploratory qualitative study, the generalizability is, of course, limited due to the interpretative nature of the study and the sample structure. Second, we analyze career aspirations at a specific point in time and life of our interviewees. Our findings do not reflect how these aspirations might change over time and with different roles of the individuals. Third, translation of categories and quotes from German into English can potentially cause a slight bias. Finally, in order to keep our sample as homogenous as possible, we limited our sample to Austrian IMEs. When looking at our results, this cultural and institutional background has to be kept in mind. Demel et al. (2009) for example point out that there exist specifics of the Austrian background such as high institutional density with a lot of legal regulations at work and a prominent role of institutional actors such as trade unions or works councils or the importance of occupations as essential elements for identity construction and individual career decisions. For the present study, this means that career aspirations of flexpatriates also have to be seen in the light of these findings. For example, depending on the embeddedness of the flexpatriate assignment into an accepted occupational profile, individuals will differ in their willingness to accept such a position and the expectations linked with this. Of course, this has consequences for the generalizability of our findings.

Quotes were translated from German into English by the first author. Labels of interviewees quoted consist of anonymised initials, type of international mobility (Exp for expatriates, Flex for flexpatriates), age, and sex (female/male).