The goal of this paper is to identify Portuguese cultural standards from the perspective of Austrian culture.

The Cultural Standards Method is based on interviews with members of one culture who have extended working experience in a different culture. This method, based on a qualitative research approach, seeks to identify cultural differences on a subtler level than more traditional methods, such as cultural dimensions.

The Portuguese cultural standards identified through interviews with 20 Austrians are as follows: fluid time management, relaxed attitude towards professional performance, importance of social relationships, bureaucracy and slow decision-making processes, indirect communication style, and flexible planning and organisational skills.

Globalisation and the dramatic increase in international business over the last few decades have meant that more and more people are experiencing cross-cultural contacts and need to be effective when dealing with partners from different cultural backgrounds within the context of their working environment.

People are usually unaware of their cultural dissimilarities until they are actually faced with another culture. Therefore, in order to be more effective at conducting business and managing across cultures, it is necessary to learn about other cultures and their characteristics. Cultural factors have progressively acquired significance as a topic of management research studies (Dahl, 2004). Many researchers and authors have written about culture models and developed cultural frameworks that provide extensive information that can be used as a basis for managers and other people to develop cross-cultural competences (Neyer & Harzing, 2008). According to Adler (1991:10) cross-cultural management focuses on studying “the behavior of people in organizations around the world… It describes organizational behavior within countries and cultures; compares organizational behaviour across countries and cultures; and, perhaps most importantly, seeks to understand and improve the interaction of co-workers, clients, suppliers, and alliance partners from different countries and cultures.”

Although an outsider might consider European cultures to be very similar, the differences among them should not be underestimated when representatives of those cultures interact.

The goal of this research project is to study the differences between Portuguese and Austrian cultures in order to identify Portuguese cultural standards from an Austrian perspective. The cultural standards are developed from an examination of intercultural encounters between Portuguese and Austrians based on the experience of Austrians living and working in Portugal. The current paper uses a relatively new methodology for researching cultural differences, called the “Cultural Standards Method”. Cultural standards are based on a qualitative research approach that seeks to identify the guidelines relevant for cross-cultural interactions. This concept is directly linked to interactive patterns and is mainly derived from the works of Boesch, Habermas, Heckhausen and Piaget (Brueck & Kainzbauer, 2002).

The main difference to highlight when comparing cultural dimensions (e.g. Hofstede, 1980; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 1997) and cultural standards is the more differentiated picture that the Cultural Standards Method provides regarding the impact that culture has on observed and experienced behaviour. Research into cultural standards includes actual problems that appear in concrete business-related encounters, how these encounters are perceived, and how and why individuals (managers, staff, etc.) react in a specific way (Fink & Mayrhofer, 2009). It is important to stress that the cultural standard method looks at differences that are only valid when comparing two cultures, while the use of cultural dimensions makes it possible to compare a wider range of countries (Kainzbauer & Brueck, 2000; Fink & Mayrhofer, 2009).

Cultural Standards MethodCultural differences have mostly been analysed using quantitative methods. The best-known categorisation of cultures is Hofstede's (1980) study, which aimed to identify cultural differences in predefined ‘dimensions’. This ‘macro perspective approach’ (Dunkel & Mayrhofer, 2001), using quantitative research tools, has been criticised because it is seen as focusing on differences between cultures on the basis of predefined categories and searching for variables ‘out of context’ (Landis and Bhagat, 1996, p. 26). Such methods focus on how people perceive themselves, but do not cover how people are perceived by others from different cultural backgrounds. What is “normal” behaviour in culture A may be perceived as being rude in culture B. In an intercultural context, however, B's perception is as important as A's intention.

The cultural standards method (Thomas, 1993), a qualitative approach to cross-cultural research, provides a way of including mutual perceptions in cross-cultural studies. According to Thomas (2007), culture can be understood as a complex system of meaningful signs and symbols that, as a whole, form a system of orientation that allows us to perceive, interpret and interact with people within the same culture in a certain manner. The core elements of this orientation system are cultural standards, which Thomas defines as follows: “Cultural standards combine all forms of perception, thinking, judgement, and behaviour which people sharing a common cultural background rate as normal, self-evident, typical and binding for themselves and for others. Thus cultural standards determine the way we interpret our own behaviour as well as the behaviour of others. (…) Furthermore, they are highly significant for perception-, judgement- and behaviour mechanisms between individuals.” (Thomas, 1993, cited in Brueck & Kainzbauer, 2002: 3)

Cultural standards are not a complete description of a culture. They are ways of seeing and interpreting the cultural experiences that certain individuals, as members of specific target groups in specific circumstances, encounter when interacting with partners from a foreign culture. However, it is also important to consider that these cultural standards are developed from what was indeed routinely experienced; that is, from what were regarded as “typical” intercultural interactions (Thomas, 2007).

Individuals who have undergone the process of socialisation in one particular culture are not conscious of their cultural standards when they interact with members of their own culture (Thomas, 1993, cited in Dunkel & Meierewert, 2004:152). Therefore, cultural standards can only be identified in a cross-cultural context, where interaction between members of different cultures occurs.

When an individual interacts or communicates with another from a foreign culture, he or she may experience unfamiliar situations that he or she is not able to interpret or understand and finds surprising. These situations are described as “critical incidents” and help to identify different cultural standards (Thomas, 1993, cited in Dunkel & Mayrhofer, 2001:5). Contrary to what the word “critical” might suggest, critical incidents do not necessarily mean negative experiences, only ones that are “not compatible with our own familiar orientation system” (Brueck & Kainzbauer, 2002:5).

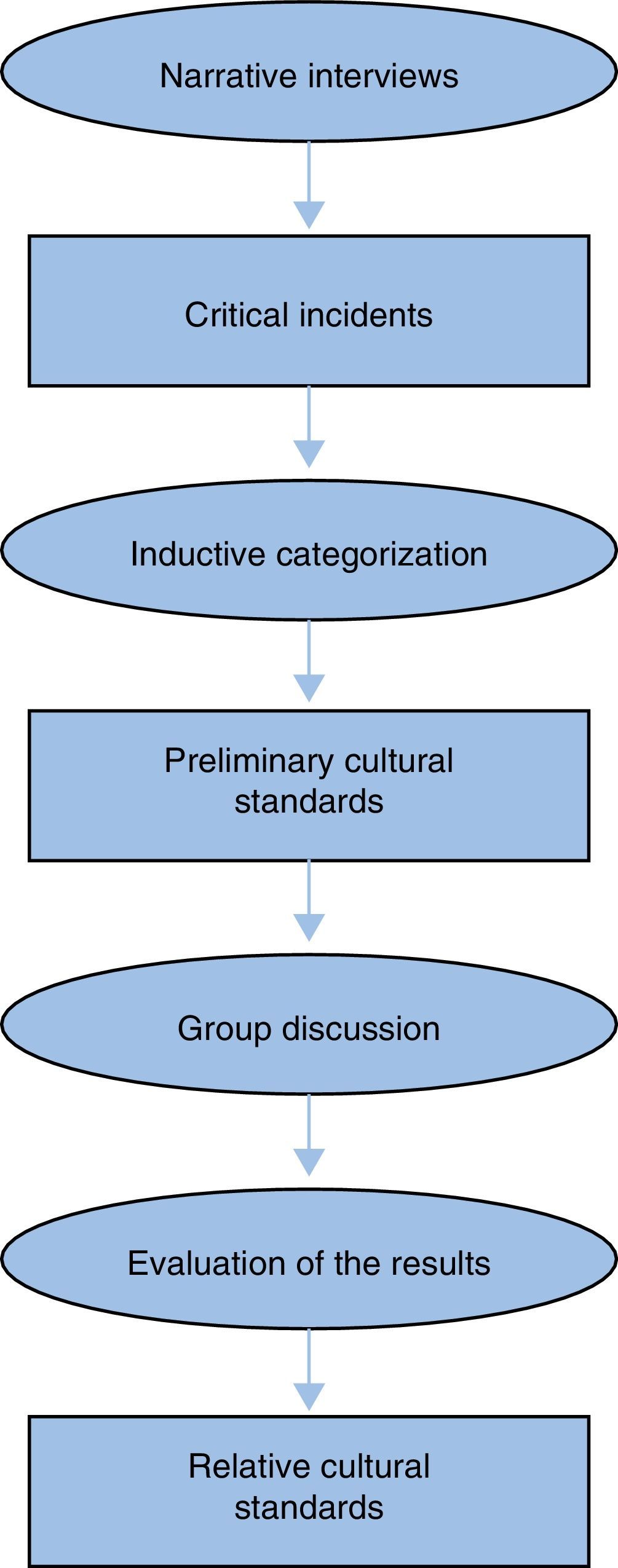

Interviewing members of one culture who have experienced encounters with members of another culture makes possible to collect critical incidents and related information. This material is then analysed and the most frequently reported incidents are collected and categorised as preliminary cultural standards. The results are then validated through the use of feedback (from experts and representatives of both cultures) and, thus, relative cultural standards can be identified (Dunkel & Mayrhofer, 2001; Brueck & Kainzbauer, 2002).

The complete research process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Cultural standard methodology (Brueck and Kainzbauer, 2002:8).

The main source of information for the cultural standards method is the narrative interview. According to Brueck and Kainzbauer (2002), this special interview technique created by Fritz Schuetze (1977) avoids the normal question-and-answer interaction between the interviewer and the respondent. Instead, this type of interview has no “leading” questions. Respondents are encouraged to talk more freely and to control the interview flow and the subject content. The role of the interviewer is that of an audience for the respondents’ narrative. Thus, this technique encourages respondents to share more information than would be the case in a normal question–answer format. The interviewer assumes a passive role that makes it possible to gather almost uninfluenced information and text material.

The literature about narrative interviews discusses different steps of the interview. According to Lamnek (1995), narrative interviews usually involve the five stages outlined below (Brueck & Kainzbauer, 2002):

- 1.

The Explanatory Stage

The main goal of this phase is to break the ice with the test person, making him or her feel less uncomfortable with the interviewer and the whole situation in order to narrate his or her story.

- 2.

The Introductory Stage

At this stage, the context of the investigation and the purpose of the interview are explained in broad terms to the respondent, to avoid influencing the story-telling and the development of the narration.

- 3.

The Narrative Stage

When the narration starts, it must not be interrupted until the respondent pauses and signals the end of the story. The interviewer should not make any comments other than probe words of encouragement to proceed with the narration or non-verbal feedback, such as nodding. The narrator controls the sequence in which information is revealed, and the more complete the information the better the investigation outcome.

- 4.

The Investigative Stage

After the narration has come to a “natural” end, the interviewer can seek to clarify doubts or complete the gaps in the story by posing questions related to the events that have been mentioned, preferably using the respondent's own words. The narrative character of the interview should not be changed and the main goal is to elicit new and additional material beyond the self-generating schema of the events told.

- 5.

The Assessment Stage

At this point it is no longer possible to go back to the narrative stage and the narration should be ended. For correct analysis of the collected data, the test person and the interviewer should now assess and interpret the stories told.

After the transcription of the recorded interviews the resulting text material needs to be analysed in order to identify critical incidents. These short stories obtained from the interviews are then examined with qualitative content analysis to extract typical behaviour patterns, which are summarised into categories in an inductive manner. Critical incidents with related background and associated to a specific behaviour are placed into the same category; these categories form the basis for cultural standards. As with all social phenomena, these categories are not strictly separated, and may instead have some overlap between them and influence each other.

While the narrative interviews are conducted with the aim to collect the respondents’ stories (which are influenced by the so-called “self-reference criterion” (Lee, 1966); that is, using your own cultural values as a basis for decisions), the content analysis and grouping/naming of categories is done by the researcher with the aim of explaining the differences from a neutral perspective. The resulting “cultural standards” are intended to be descriptive rather than normative.

In order to evaluate these preliminary cultural standards, a group discussion with some of the interviewed persons and with bicultural experts is conducted; their feedback helps to confirm the compiled cultural standards. In this group discussion, participants are asked to confirm whether the critical incidents collected are indeed typical of the Portuguese culture. They are also asked to substantiate the identified cultural standards by exploring reasons for the Portuguese behaviour and their culture-specific background. This process helps to exclude any atypical situations that could distort the research outcome, since the results are intended to demonstrate typical cultural distinctions between the two cultures rather than just personal experiences (Brueck & Kainzbauer, 2002). Finally, the identified cultural standards are compared with existing literature on cultural differences where available.

Results from the empirical researchThe research design used non-random (non-probabilistic) sampling (Collins, Onwuegbuzie, & Jiao, 2006:83). The main criterion used to select respondents was that they had to be Austrian and have a minimum of one year of working experience in Portugal.

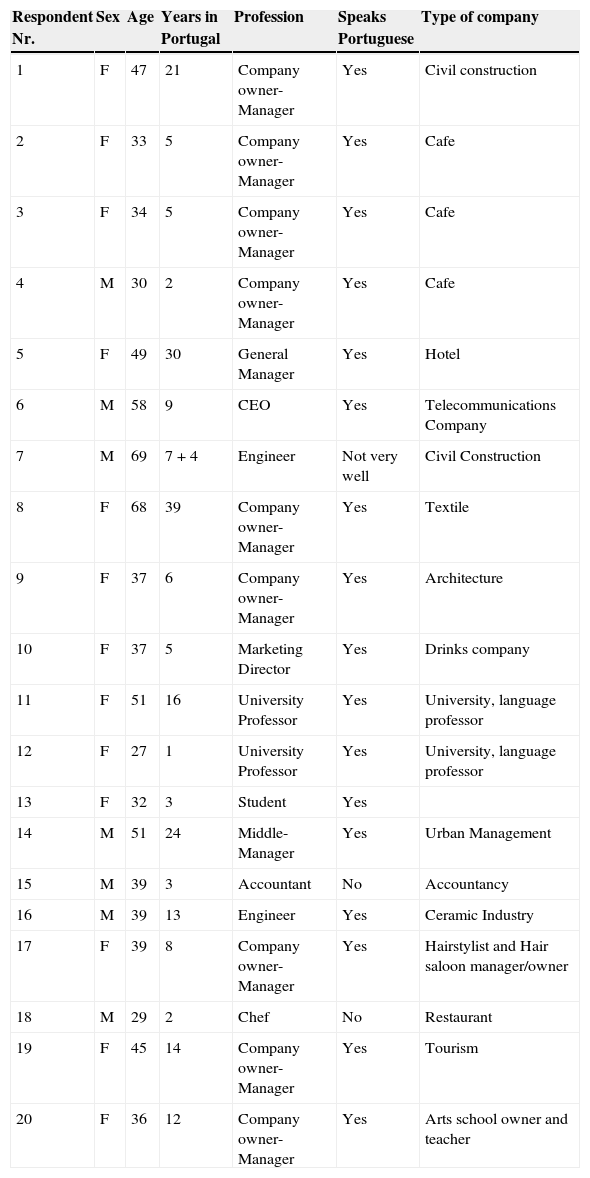

The sample group (see Table 1) was made up of 20 people (13 women and seven men). The number of respondents was determined by the concept of “theoretical saturation”; that is, interviews were conducted until no new themes were observed in the data (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006). The respondents form a heterogeneous sample, representing different regions of Austria and professional experience from different areas, including education, architecture, food and beverage, tourism, telecommunication, textiles, and ceramics. One-third of the respondents have developed their own businesses in Portugal. The average age was 42 years and the average length of stay in Portugal was 11 years. The respondents were easily convinced to participate in this study as many of them saw the interviews as opportunities to share their cross-cultural experiences. See list of respondents in the appendix (Table 1).

List of respondents.

| Respondent Nr. | Sex | Age | Years in Portugal | Profession | Speaks Portuguese | Type of company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 47 | 21 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Civil construction |

| 2 | F | 33 | 5 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Cafe |

| 3 | F | 34 | 5 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Cafe |

| 4 | M | 30 | 2 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Cafe |

| 5 | F | 49 | 30 | General Manager | Yes | Hotel |

| 6 | M | 58 | 9 | CEO | Yes | Telecommunications Company |

| 7 | M | 69 | 7+4 | Engineer | Not very well | Civil Construction |

| 8 | F | 68 | 39 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Textile |

| 9 | F | 37 | 6 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Architecture |

| 10 | F | 37 | 5 | Marketing Director | Yes | Drinks company |

| 11 | F | 51 | 16 | University Professor | Yes | University, language professor |

| 12 | F | 27 | 1 | University Professor | Yes | University, language professor |

| 13 | F | 32 | 3 | Student | Yes | |

| 14 | M | 51 | 24 | Middle-Manager | Yes | Urban Management |

| 15 | M | 39 | 3 | Accountant | No | Accountancy |

| 16 | M | 39 | 13 | Engineer | Yes | Ceramic Industry |

| 17 | F | 39 | 8 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Hairstylist and Hair saloon manager/owner |

| 18 | M | 29 | 2 | Chef | No | Restaurant |

| 19 | F | 45 | 14 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Tourism |

| 20 | F | 36 | 12 | Company owner-Manager | Yes | Arts school owner and teacher |

The majority of the respondents stated they really enjoy Portgugal and their local quality of life. The most commonly emphasised aspects were the friendliness of people, the climate, the landscape and the food.

The Portuguese cultural standards, as identified in this study from an Austrian perspective (ranked according to the number of references in the interviews) are:

- 1.

Fluid time management

- 2.

Relaxed attitude towards professional performance

- 3.

Importance of social relationships

- 4.

Bureaucracy and slow decision-making processes

- 5.

Indirect communication style

- 6.

Flexible planning and organisational skills

In international management the “time factor” may become a significant source of misunderstanding and even create conflict. Time management concepts, both for companies and individuals, are embedded in the context of markets and societies, which means they are not easily transferred across cultures (Fink & Meierewert, 2004).

One of the most obvious differences between Austrians and Portuguese has to do with punctuality, deadlines and the general “rhythm” of daily life. Hall and Hall (1990) used the terms “monochronic” and “polychronic” to refer to a more sequential, deadline-oriented use of time, or a more fluid and flexible use of time, respectively. In our study, 18 of the Austrian respondents (90 percent) mentioned that the Portuguese have a different attitude towards time than they do.

PunctualityOne of the main aspects of this cultural standard is punctuality or, in this case, the lack of it. In Austria, the lack of punctuality is considered impolite and when someone is late they must present a good and valid excuse. As most of the respondents mentioned, the normal behaviour in Portugal is to arrange meetings for a certain hour and then arrive late to them. This attitude towards time is something that many of the Austrians still find somewhat difficult to accept. As respondent 16 noted: “At work, when we had meetings, I was the only one to be there on time, even fiveminutes earlier, which for us is a standard of good manners, but the others only started to appear 10 or 15minutes later and the room would be complete only 30minutes after scheduled time. And the last to arrive was usually the one with the higher position. That was very traumatizing for me in the beginning. And in terms of being productive that is also very bad, since in those 30minutes I could have done many other important things. For company productivity, it's easy to do the math – to have six employees waiting 30 minutes for a meeting to start means hours of lost labour.”

This is usually even more marked in informal meetings where “late” can be up to an hour after the agreed time, as the same respondent illustrated. Respondent 12, who had been living in Portugal for a year, emphasised how shocked she was about the lack of punctuality.

DeadlinesAnother feature of this cultural standard has to do with deadlines; specifically, not adhering to them. The respondents noticed that deadlines in Portugal are usually not adhered to; this was mentioned in several contexts from presenting projects to deliveries of merchandise and payments. As Respondent 3 explained, “I learned that «amanhã» [tomorrow] in Portuguese has a completely different meaning than in German.” For Austrians, who are used to respecting deadlines this more “flexible approach” of the Portuguese can be an additional source of stress, as Respondent 12 said: “Deadlines are less strict than in Austria. Once I had to do a project and I was very concerned I wouldn’t be able to finish it on time. I explained the situation to a colleague and she replied there was no reason to be worried, that I could perfectly deliver it two or three days after the deadline that no one would notice it. And so I did it, even though that left me quite nervous, but in fact nobody said anything.”.

The lack of punctuality and not sticking to deadlines were also mentioned in a 2002 survey on Portuguese management (Bennett & Brewster, 2002).

Rhythm of daily lifeTime management is also related to the rhythm of daily life. More than half of the respondents said that people in Portugal live at a slower pace, in a more relaxed way and “apparently” with less stress than in Austria. The word “apparently” is used because some of the respondents also mentioned that due to their more relaxed relation towards time, many Portuguese seem to rush to their meetings and scheduled activities, being aware that they are already late. Respondent 3 said: “One of the things I really had to practise in Portugal was to be patient. I really had to learn that because in Portugal one always spends many hours waiting: in traffic, in the queue at the post office, at the hospital, etc. And also when someone says ‘I’m arriving’, it doesn’t mean he or she will arrive in the next two minutes; it can be for example only 20 minutes later. That I really had to practise!”

This rhythm of daily life was also mentioned in relation to the distribution of time during a working day, during which Portuguese people usually take several coffee-breaks and long lunch breaks and seem to have quite a relaxed attitude towards working time. Several of the respondents mentioned that in Austria people usually have a lunch break of 30minutes or less in order to get their work done and be able to go home as early as possible. In Portugal, lunch is seen as a very important meal and also as a social meeting with colleagues or friends, which is also related to the “importance of social relationships” cultural standard, as explained later.

Relaxed attitude towards professional performanceEighty percent of the respondents (16 out of 20) felt that Portuguese have a different attitude towards work than Austrians. The respondents considered that Austrians generally take their job more seriously, and more self-disciplined concerning their duties on the job and spend working hours more focused on their tasks, spending less “working time” in coffee-breaks or chatting with colleagues. Some of the respondents also related this less committed attitude towards work with a less efficient performance of Portuguese workers. This is in line with the results of the Globe study which found Austrians to be more achievement oriented than Portuguese (Koopman, Den Hartog, & Konrad, 1999). These findings may also be echoed in the 2013 World Competitiveness Ranking published by IMD, in which Portugal ranks 46th out of 60 countries, considerably lower than Austria at 23rd.

In relation to the achievement of results, the respondents found that the Portuguese mainly aimed for the minimum level considered satisfactory and were more willing to accept less-perfect solutions, while Austrians sought excellence. As Respondent 10 said: “In the professional part, our culture is more demanding and here in Portugal everything is just «more or less». This was difficult for me to understand since I’m used to do things in a very perfectionist way. In meetings with partners I found situations where things were not lousy but they weren’t perfect either, and so in the beginning people used to be a little shocked with my remarks and my level of exigency”. Respondent 2 also spoke about the different attitude towards results: “I’m very perfectionist but here I had to learn that is difficult to achieve since things usually don’t work out at first time and then there is a need to improvise for alternative solutions that won’t be perfect. On the other hand it's good because you don’t have so much stress to achieve certain goals.”

As several respondents noted, this issue may be linked to a general lack of professional training, especially at intermediate levels. The Austrian education system enables students who do not wish to proceed with their studies at the university level to learn a profession, instead of entering the job market without specific qualifications as happens in Portugal. Due to this difference in education systems, people in Austria are more aware of the need to have professional training not only as professionals (workers) but also as consumers/customers, becoming more demanding towards those who provide services and goods.

Another aspect mentioned by the respondents was the lack of initiative and the reluctance to change things. In general, the respondents felt that Portuguese people were be less proactive, more conformist with the current situations and less willing to take risks. Respondent 8 said: “People here are not very ambitious, they don’t leave the standard course to achieve more, and they are not very motivated to draw their own path. Maybe the fact that we had war at home and several privations lead us to be more pro-active.” Respondent 5 had a similar opinion: “I think Portuguese are more conformist, which does not necessarily have to be a negative thing. This accommodation is something very intrinsic in Portuguese society.”

One way of explaining the Portuguese unwillingness to take responsibility is their tendency to attribute events and their causes to external forces rather than believing that the outcome depends on their own actions (Bennett & Brewster, 2002).

Customer orientationIn relation to professional attitude, the respondents also mentioned that the Portuguese are less service-minded than Austrians. This opinion was also shared by foreign managers from several European countries in a 2002 survey on Portuguese management (Bennett & Brewster, 2002). In the present study, this point was mentioned mainly in relation to services provided in shops, restaurants, cafes, hotels but also at healthcare providers or public services. The main issues were the lack of professionalism, a non-friendly attitude, or the employees’ lack of motivation. Respondent 10 said: “There are people who work a lot and are professionally very valuable and then there are people a little lazy. Of course this exists everywhere but here I noticed there are too many people that don’t have motivation to do their job.

The last aspect of this cultural standard was mentioned in relation to the difficulty of obtaining accurate information from several service providers, both in the public and private sectors. The respondents mentioned that they were given inaccurate answers when they asked for information in a shop or in the city hall, for example. Some respondents related this less consumer-oriented behaviour with the less self-demanding attitude of the Portuguese towards their job duties, while others related it with the lack of adequate professional training in Portugal.

Importance of social relationshipsAs human beings, we live in diverse types of societies where social relationships can play different roles. Portuguese tend to establish tight social networks and value personal relationships highly. Both Hofstede's study (1980) as well as the Globe Study (Chhokar, Brodbeck, & House, 2007) found that Portugal is a more collectivistic society than Austria. The Portuguese focus on social relationships was also confirmed by Jesuino (2007), who emphasised that Portuguese managers exert their influence and foster their goals through social networks. Three-quarters of the Austrian respondents (15 out of 20) in our study mentioned the important role that social relationships play in Portugal.

FamilyThe most striking feature of this cultural standard is related to the importance of family relations. In Portugal people maintain close contact with their family, not only their nuclear family (parents and siblings) but also their extended family (including several generations, cousins, aunts and uncles). Family members meet each other on a regular basis, sometimes as often as once a week. In Austria, on the other hand, family contact is not so present in daily life and family members tend to meet less often. Respondent Number 15 said: “Another different thing is the family. I like very much that the family has a very high value in Portugal; people like to see the family at weekends, some people I know want to share at least one day of the week with their family.”

Another main difference pointed out by the respondents is that in Portugal children tend to live with their parents up to an older age (mid-20s), usually leaving the parents’ home when they get married. In Austria, young people are encouraged to start their own independent life sooner, around age 18.

FriendshipThe respondents spoke about the hospitality they felt in Portugal and how people are generally very kind and willing to help if they can, even when they do not really know each other. However, they also mentioned that, despite this warm welcome, it was quite difficult to establish solid friendships with Portuguese after the first meetings. The respondents interpreted this difficulty as a reflection of the important role family relations have in Portugal. As Respondent 11 said: “People are kind and help me a lot if there is any problem. In Austria people are not so willing to help strangers; there is more distance between people in the beginning. In Portugal there is less distance in the beginning but then this distance remains. In Austria there is more distance in the beginning but then it's possible to make friends with a very intimate relationship. That didn’t happen with me here.”

Another aspect pointed out by the respondents was the different meaning of the word “friend” in the two countries. In German, the word “friend” is applied only to close friends, while the term “Bekannte” (acquaintance) is used for people that you know but do not have a close relationship with. In Portuguese, the term “friend” is normally used in a broader sense and this distinction between friends and acquaintances is not usually made, leading to the impression one has many friends.

Interpersonal space and physical contactAnother issue related to social relationships that came up during the interviews has to do with physical contact and interpersonal space. Hall (1966) referred to this dimension as “proxemics”. The respondents referred to the differences in nonverbal greetings between the two countries. While in Portugal it is common, even for strangers, to greet each other with a kiss on each cheek, while in Austria this form of greeting is usually confined to intimate relationships, such as family and close friends, with a handshake being used when meeting someone new. The respondents also mentioned how this way of greeting makes people physically closer to each other, leading to a smaller so-called “space bubble” than in Austria. This difference in interpersonal distance can make a person from a more distant culture, such as Austria, uncomfortable.

Respondent 3 shared how she experienced this different approach: “When I meet someone from my bank I don’t want to greet him or her with kisses on the cheek. We are not used to it; we only kiss friends or someone really close. But I have never given kisses to my bank account manager in Austria. That is something unimaginable! It's not good or bad, it's just very different. Even today I have troubles kissing someone with whom I might be angry with due to professional reasons. That does not work for me.” Respondent 15 mentioned how the interpersonal space difference caused him some discomfort in the beginning: “At the office I had a colleague who came too close in order to talk to me and at the beginning that was a little uncomfortable.”

Bureaucracy and slow decision-making processesBureaucracy can be defined as an administrative system marked by clear hierarchical authority, rigid division of labour and the need to follow rigid and inflexible rules and regulations.1 Bureaucracy is usually set in place in large organisations to control activity by using standardised procedures, intended to minimise unexpected situations and improve efficiency.

Sixty-five percent of the respondents (13 out of 20) felt there is too much useless bureaucracy in Portuguese society in general, which slows down decision-making processes, steals time from other important tasks and contributes to inefficiency. This perception was also shared by foreign managers from several European countries in a 2002 survey on Portuguese management (Bennett & Brewster, 2002). From an Austrian perspective, some of the situations experienced by the respondents in the context of bureaucracy can be seen as quite bizarre and patience was usually required in order to learn the rules. Respondent 7 explained the differences between the two countries as follows: “Here many administrative procedures are very complicated; you always have to write your parents’ names, in several different papers and things are quite inefficient. I get mad sometimes! Just recently, when I had to renew my driving licence, I went to the doctor to check everything was fine, did all the tests and at the end I received a small paper to replace my licence temporarily and I was informed that paper was valid for a year. I thought to myself, ‘Does this mean it will take a year to receive my new licence?!’ I was completely shocked! In Austria when I changed my address once, I also had to change my car's licence plate. I went to the appropriate department, gave the employee the papers and he told me to grab a coffee and return in 15minutes to receive it back! What a difference.”

These bureaucratic systems are present in public administration and in companies, but are more noticeable in the former. Many of the respondents opened their own business in Portugal, having to deal very closely with bureaucratic issues. Some, who had been living in Portugal for a longer period of time, mentioned there had been considerable improvements over the last few years, particularly with regard to online services, although in many situations it is often required to be physically present in order to take care of issues.

In relation to bureaucracy, the respondents also mentioned that despite all the inflexible regulations and procedures, people tend not to play by the rules and in general find a “way around” them; that is, they find alternative ways to facilitate a bureaucratic process. In Austria, things work smoothly and people generally tend to follow the rules in place.

Indirect communication styleHow people express their opinions and communicate with each other, as well as the way they deal with criticism and disagreement, can vary greatly from culture to culture.

Some cultures tend to value direct, clear-cut language, while others favour a more indirect “in between the lines” style. Misunderstandings arise because people from different cultures have different expectations towards the communication process (Gesteland, 2005). Hall (1976) referred to these different communication preferences as “high-context versus low-context communication”.

Just over half of the respondents (11 out of 20) mentioned differences in the ways Austrians and Portuguese communicate.

Indirect communicationFrom an Austrian perspective, Portuguese communicate in an indirect way, not expressing what they mean directly, but using hidden meanings and metaphors and expecting that the other person can “read between the lines”. This also implies that conversations usually last longer in Portuguese, since the indirect communication style uses more words and sentences than a more straightforward one. This last point can also be related to the structural differences between the Portuguese and German languages.

Respondent 2 explained this point clearly and also noted how these differences can be seen in a positive light: “Our culture is more direct. We use shorter sentences, which for a Portuguese may seem more brutal and impolite. It might be also related to the structure of our language. What I usually say in German using one sentence usually takes me five or six sentences. On the other hand these language differences are a nice thing because you get to talk more with people and have the chance to know them better.” Respondent 3 said: “One thing that I’ve noticed is that people don’t like it when we are too straightforward; if something is like it is, we say it clear-cut; or when we don’t like something we also say it clearly. But in Portuguese you don’t say things in this way. In Portuguese you usually talk around 10minutes before actually saying what you mean, while we, the Germans and the Swiss would say it in the first sentence. We are not used to talking for so many minutes about a short topic.”

Difficulty in saying “no” and criticisingAnother feature of this indirect communication style is that the Portuguese have difficulty saying “no” and expressing dislike towards people or situations. This is also reflected in the difficulty Portuguese have in expressing opposing views and in openly criticising other people, in fear of offending them personally. As a more collectivistic society (see the “importance of social relationships” cultural standard), the Portuguese place a high value on their personal and professional relationships, avoiding situations that might end in open conflict/disagreement between the parties involved.

Respondent 19 described how the Portuguese say “no”: “We go to meetings, and everything seems to be all right, but then the Portuguese are incapable of saying ‘I’m not interested’ or ‘we can’t do that now, we have to postpone it for a few months’. They just don’t say anything else anymore; they don’t answer our proposals… they just disappear. The Portuguese don’t want to be unpleasant and instead of saying something that will not be nice they prefer not to say anything at all.” Respondent 20 explained how hard it was for her to learn the way to say “no” in Portugal: “One of the things that was very difficult for me, mainly socially, is that the Portuguese don’t say ‘no’. Here, if someone has an invitation and can not go, instead of saying ‘I’m so sorry, but I can’t go’, they always say ‘thank you very much for the invitation, I would love to go, I’ll do my best to attend’. For years I really thought that when people said this, they would eventually come to the meetings – until someone told me this was the Portuguese ‘no’. And people really feel offended when I look into my agenda and I already know one week in advance that I can’t go to the dinner or so. They conclude that it's because I don’t want to, so I learned to do as they do it here.”

The other aspect related to the communication style is the apprehension people have in openly expressing their opinion when it might cause discomfort to other persons involved. Even when they are asked directly to express their opinions, for instance, about the service they were provided with, they feel reluctant to do so. Respondent 14 explained: “Portuguese have a fear of criticising. While abroad it's seen as way of participating in the development and improvement of things, in Portugal it's seen as very negative thing. When a Portuguese is about to express a critical opinion, he already starts by apologising: ‘I’m sorry, this is nothing personal but…’.”

One way Portuguese use to avoid confrontational situations is through the use of a third person or other indirect communication channels.

Flexible planning and organisational skillsThe analysis of the empirical data made it possible to identify another cultural standard: “planning and organisational skills.” Half of the respondents (10 out of 20) referred to the lack of planning in Portugal along with a lack of organising skills compared to Austria. This result can be linked to the Globe Study, where Austria was found to rank much higher on “future orientation” (which includes planning ahead) than Portugal does (Koopman et al., 1999). In fact, Portuguese scores in this dimension were lower than the Globe average (Jesuino, 2007). In the present study, participants mentioned that Portuguese people are generally not concerned about planning ahead and establishing plans that are meant to serve as guidelines for dealing better with unexpected situations. Quite often, things are not considered in advance and are handled at the last minute, which can lead to additional stress, as mentioned in relation to the cultural standard “Fluid Time Management”. Respondent 20 said: “One has to accept that here many things are made haphazardly and there is a general lack of planning. For instance, we sometimes want to plan things thoroughly and ask something with the necessary time and we face reactions such as: ‘Ah! But there is still a lot of time for that; it only takes place in half a year!’ It's hilarious.” Respondent 15 spoke about the lack of organisational skills in order to find permanent solutions that can bring more efficiency to work: “When you have a problem, the solution can go in different directions. My impression is that Portuguese people don’t look so much to the one which is a permanent solution [where you don’t have to do any more work afterwards] but can but which can take more time. Instead they just think in any solution, just to solve the problem, but which means you have to do it and work on it every month again. … On the other side, if there is an urgent problem it is fantastic how fast the Portuguese solve the problem and find a way to deal with it. I was really impressed with their approach and how people motivate themselves to find a solution.”

Last-minute problem solving – “desenrascar”The respondents pointed out that due to their lack of planning and organisational skills, Portuguese people face many unexpected (non-planned) situations, which made them very good at improvising and finding alternative solutions. The Portuguese have a characteristic word to describe this type of “last-minute problem solving behaviour”– desenrascar – which was used by all the respondents in relation to this topic and can be translated as “to improvise” or “to disembarrass”. Respondent 10 said: “Here things aren’t planned and people have a great capability of improvising [desenrascar], but then there is lots of stress due to the lack of planning, and some things happen to work well anyway but others not really. It wasn’t easy to motivate people to start planning things with the appropriate time in advance and to teach them to forecast different scenarios with details. It's something that takes a lot of work in the beginning but generates a better outcome afterwards. There is also a lack of organisation.” The Portuguese skill of “desenrascar” was also mentioned in a 2002 survey on Portuguese management (Bennett & Brewster, 2002).

Another thing that the respondents mentioned was the Portuguese spirit of not giving up, even when a situation might seem hopeless from an Austrian perspective, and how they can generally provide at least a satisfactory solution for problems. Respondent 14 said: “Portuguese leave the details of many projects to be decided later on without much planning, which brings last-minute problems and the need to find solutions for them. And in this Portuguese are really very good, which I think is a great quality. I lived in other countries, for instance in Italy, and they aren’t like this. At a certain point they stop and say there aren’t conditions to continue anymore. While the Portuguese say no, they always try to solve the situation, they don’t give up. What is missing is the structure, the basic planning.” Respondent 3 also referred to this, saying: “Before I had my own business I worked for an Austrian company here that participated in the organisation of Euro 2004 in Portugal. They were in charge of catering and staff for sponsors, VIP areas, etc. … Even though they brought many people from Austria, they also had to work with Portuguese teams and they had several problems with things that weren’t ready when they were supposed to be. While the Austrians were already thinking it was too late and things were doomed, the Portuguese never gave up. It was amazing. I don’t know how they did it but in the end things actually worked after all. At the last minute things always worked out!”

FeedbackIn order to evaluate the identified cultural standards and obtain feedback, the results of the empirical research were sent to the interviewed persons as well as two more Austrians with work experience in Portugal who had not participated in the interviews, and could therefore be considered as an external source of feedback. All respondents gave strong support for the results.

Nevertheless, Respondent 7, who gave more in-depth feedback, exhibited some concerns with the obtained results: “I suggest that you take into consideration that attitudes towards and views on foreigners of Portuguese are the opposite of those of Austrians: whereas Austrians often consider foreigners as ‘inferior’, have little understanding for the foreigners’ ways of doing things (differently) and believe that their ways are the (only) correct ones, Portuguese usually show a lot of interest in foreigners, have a lot of admiration for foreigners, and often believe that foreigners are ‘superior’ to the Portuguese…and your Portuguese biases might well amplify the effect of the biases of the Austrians you interviewed.” In relation to the bureaucracy and slow decision-making processes cultural standard, the same respondent observed that things are changing quite fast nowadays and there are already several simplified services in the public administration. Examples include “Empresa na Hora” (a service that makes it possible to establish a company on the spot), which is something that is not possible in Austria and is working well in Portugal, and “Loja do Cidadão”, where one can handle most administrative processes in only one building. The respondent added that he does not agree with the view of Portuguese as being less efficient, referring that there are several examples of multinational companies operating in Portugal who achieve better performance indicators than any other of their respective European subsidiaries.

ConclusionsThe goal of this research project was to examine cultural differences that emerge from the encounter between Austrians and Portuguese from the Austrian perspective. The research results are Portuguese cultural standards that are relevant for Austrians during such encounters, and which can serve as a basic orientation guideline for Austrians interacting with Portuguese.

The identified Portuguese cultural standards are:

- 1.

Fluid time management – Portuguese were seen as having a more fluid time management than Austrians concerning punctuality, deadlines and rhythm of daily life.

- 2.

Relaxed attitude towards professional performance – The Austrians saw the Portuguese as being more relaxed towards professional performance, described mainly as having less self-discipline concerning their duties on the job, not being so perfectionist and being less willing to take risks. Two other characteristics mentioned were the general lack of professional training and a less consumer-oriented behaviour.

- 3.

Importance of social relationships – The social relationships in one's life, especially concerning family relations, were considered to play a more important role for Portuguese than for Austrians. Austrians also emphasised the difficulty of establishing strong friendships and entering into Portuguese social circles. They also referred to the smaller “space bubble” they experienced in Portugal, together with a more physical approach during social encounters.

- 4.

Bureaucracy and slow decision making processes – Austrians felt there is too much useless bureaucracy in Portuguese society in general, which slows down decision-making processes. In relation to this, it was also mentioned that despite the existence of many rules, Portuguese tend to ignore them or find a way around them.

- 5.

Indirect communication style – Austrians found that Portuguese communicate in an indirect way; they pointed out the Portuguese difficulty in saying ‘no’ and in openly expressing dislike or opposing points of view.

- 6.

Flexible planning and organisational skills – Portuguese were considered to lack organisational skills and to be not very concerned with detailed planning. Additionally, Austrians found Portuguese to have a great capacity to improvise and find alternative solutions and not to give up when faced with what may seem a “hopeless” situation.

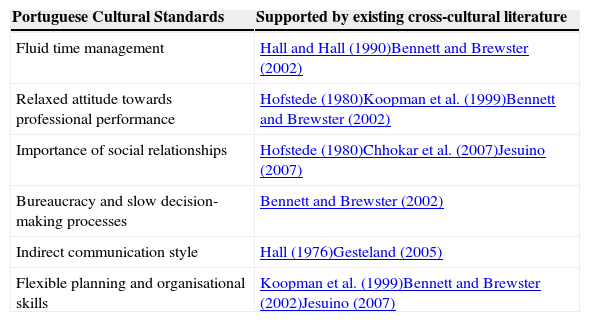

Some of the cultural standards identified in this study can be related to existing studies on cultural differences (see Table 2). Fluid time management is similar to Hall's polychronic time management; relaxed attitude towards professional performance is reflected in the Globe Study's achievement orientation; importance of social relationships can be linked to Hofstede's collectivism; and indirect communication style can be related to Hall's high-context communication. The remaining cultural standards (bureaucracy and slow decision-making processes, as well as flexible planning and organisational skills) are unique dimensions that do not link to existing studies on cultural differences. However, the underlying behaviours of these two cultural standards are also discussed in Bennett and Brewster's survey on Portuguese management (Bennett & Brewster, 2002). Table 2 summarises the links between the identified cultural standards and existing literature.

Links between cultural standards and existing cross-cultural literature.

| Portuguese Cultural Standards | Supported by existing cross-cultural literature |

|---|---|

| Fluid time management | Hall and Hall (1990)Bennett and Brewster (2002) |

| Relaxed attitude towards professional performance | Hofstede (1980)Koopman et al. (1999)Bennett and Brewster (2002) |

| Importance of social relationships | Hofstede (1980)Chhokar et al. (2007)Jesuino (2007) |

| Bureaucracy and slow decision-making processes | Bennett and Brewster (2002) |

| Indirect communication style | Hall (1976)Gesteland (2005) |

| Flexible planning and organisational skills | Koopman et al. (1999)Bennett and Brewster (2002)Jesuino (2007) |

The qualitative research approach applied in this study provides a number of advantages. Most importantly, it allows a greater differentiation of cultural differences, which is particularly useful in the case of closely related cultures, where the differences might not be immediately obvious. Due to the relative nature of cultural standards, cultural comparisons that are based on this method show a greater depth of detail. The results illustrate subtle differences between cultures, as perceived by members of one culture who have been interacting with members of the other culture. The focus here is on the perception of the behaviour of others. Quantitative cultural studies (Hofstede, 1980; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 1997) typically focus on the assessment of one's own culture and omit the important aspect of how one's behaviour is perceived by others. However, it is mostly the perception by others that causes difficulties and misunderstandings in intercultural interactions. The emotional impact of cultural misunderstandings is made visible through narrative interviews and can then be included in the description of relative cultural standards in order to explain the perceptions of the interaction partners. This detail of information would hardly be available through quantitative research.

Another advantage of this method is that cultural standards only emerge in cross-cultural bilateral situations if they are relevant for action (Dunkel & Mayrhofer, 2001). Therefore, the derived information is defined by the respondents’ real-life experience and not ex ante determined by the researcher, as is the case in quantitative studies. This is further supported by the fact that even though some of the cultural standards derived in this study can be linked to individual dimensions used by other researchers (Hofstede, Hall, Globe Study), they do not link to an entire set of dimensions (for example, all of Hofstede's dimensions). This shows that using an existing set of dimensions would not have captured the concerns of Austrians working in Portugal adequately.

The bilateral relevance of the cultural standards can also be confirmed by comparing our results with the results of an existing study on cultural standards in Austria and Spain (Dunkel, 2001). While some of the cultural standards identified in Dunkel's study are similar to the Austria – Portugal study (such as different interpretation of time, personal relationships), there were also several different aspects (gender roles, authority, face-saving). Therefore, care should be taken when trying to extrapolate the meaning of cultural standards beyond their original cultures to ‘supposedly’ similar cultures.

Finally, the cultural standards method is of high practical relevance because the results are valuable sources for management training. The critical incidents derived in narrative interviews can be used as short case studies in training situations. Because they are based on real-life experiences, these incidents provide a great resource for trainers whose task is to make their trainees aware of typical difficulties faced in cross-cultural situations. Therefore, cultural standards research is often conducted with the aim of providing a culture specific training tool for expatriates (Thomas 2007).

From a practical perspective, the results of the current work can serve as the basis to develop culture specific training tools that can be used to train Austrian expatriates or business people interested in doing business in Portugal. Such culture assimilators aim to increase cultural awareness and help participants to develop intercultural skills, which are a key factor for successful business relations in foreign countries.

A limitation of the current study is that it only captures one side of the picture; that is, the Austrian perception of Portuguese culture. It would be interesting to develop the research further by conducting a reverse investigation about Austrian culture from a Portuguese perspective and compare the results with the Portuguese cultural standards identified. This would make it possible to have a broader vision about cultural interactions between Portuguese and Austrians.