This study aimed to provide a comprehensive nationwide assessment of the status of nursing management in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

MethodsA nationwide observational cross-sectional survey study was conducted. Nurses involved in the care of patients with IBD completed the 90-item Nursing Care Quality in IBD Assessment (NCQ-IBD) questionnaire which classifies the level of quality of care from A (highest) to D (lowest).

ResultsA total of 71 f questionnaires were analyzed. In this study, category A was achieved in 2 (2.8%) cases, category B in 53 (74.6%), and category C in 16 (22.5%). Of the list of 27 professional competencies identified for a specialized IBD nurse, 23 (85.2%) were met by more than 70% of participants. Regarding the presence of specific nursing IBD care only 28 (39.4%) worked for more than 4.5days/week. About 88.7% of nurses used clinical practice guidelines or protocols and 74.6% applied scales for assessing anxiety and depression, but just 18.8% and 25.4% evaluated IBD classification and activity indexes, respectively. Only 53.5% of participants reported to have available training plan in IBD. In the last 5 years, 25.4% of professionals had participated in more than five research projects, 9.9% had presented more than five communications in meetings, and 14.1% had published more than three articles.

ConclusionsNursing care was highly satisfactory. Signage on nursing consultation doors, administrative support, holiday coverage, encouraging research, and primarily increasing the ratio of nurses working full-time, are areas for improvement.

El objetivo del estudio fue evaluar a nivel nacional, el estado actual de la atención de enfermería en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII).

MétodoEstudio observacional, transversal, tipo encuesta. Los participantes completaron el Instrumento de Evaluación de la Calidad Asistencial de la EII por Enfermería (IEC-EII) de 90 ítems que clasifica el nivel de calidad del cuidado en 4 categorías: A (más alto) a D (más bajo).

ResultadosSe analizaron 71 cuestionarios. En este estudio, la categoría A se alcanzó en 2 (2,8%) casos, la B en 53 (74,6%) y la C en 16 (22,5%). De las 27 competencias correspondientes a enfermería especializada en EII, 23 (85,2%) se alcanzaron en más del 70% de los participantes. Respecto a la presencia de cuidados de enfermería específicos para EII, solo 28 (39,4%) trabajaban más de 4,5 días/semana. Además, el 88,7% utilizaba guías de práctica clínica o protocolos, y el 74,6% aplicaba escalas para evaluar la ansiedad y la depresión. Únicamente el 18,8% evaluaba la clasificación de la EII y el 25,4% los índices de actividad. Asimismo, solo el 53,5% manifestaba tener acceso a un plan de formación en EII. En los últimos 5 años, el 25,4% de los profesionales había participado en más de 5 proyectos de investigación, el 9,9% había presentado más de 5 comunicaciones en congresos y el 14,1% había publicado más de 3 artículos.

ConclusionesLa calidad de la atención enfermera fue altamente satisfactoria. Las áreas de mejora detectadas: la señalización de las consultas enfermeras, el soporte administrativo, la cobertura durante vacaciones, el estímulo a la investigación y, especialmente, la tasa de enfermeras a jornada completa.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract, consisting of Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), characterized by an abnormal immune response in genetically susceptible individuals after exposure to environmental factors that alter their intestinal microbiome.1,2 The prevalence of IBD surpasses 0.3% in North America and Europe,3 but has become a global disease with an accelerated incidence in newly industrialized countries with westernized life style changes. It has been recently estimated that a compound prevalence in North America, Europe, and Australasia will reach 1 in 100 persons by the end of this decade.4 In Spain, an overall incidence of IBD of 16 cases/100,000 person-years has been reported.5 However, the prevalence is increasing rapidly and it has been suggested that in major industrial regions the number of patients may double in approximately 10 years (2018–2028).6

The rising epidemiological trends in a lifelong illness for which there is no cure pose a high economic burden for healthcare systems with increasing consumption of health resources in otherwise progressively aging of IBD populations.7,8 Also, the chronicity, polymorphic clinical features, and high comorbidities and complications of IBD have a tremendous impact on the patients’ health and quality of life.9 Integrated care models as dedicated IBD units based on multidisciplinary teams (MDT) involving comprehensive care by IBD nurses, surgeons, psychologists, dieticians, pharmacists and other members, with structured monitoring, active follow-up, patient education and prompt access to care has been shown to improve outcomes and decrease costs compared with a more traditional physician–patient model.10–13

The key role played by specialized nurses in the management of patients with IBD has been extensively recognized.14,15 The Nurses European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (N-ECCO) has provided updated consensus statements addressing standards of IBD nursing care and evidence-based guidance enabling IBD nurses to cope with advanced care and encouraging research.16 The “Nursing Now” three-year global campaign (2018–2020) run in collaboration with the World Health Organization and the International Council of Nurses aimed to improve health globally by raising the status and profile of nursing.17 Different surveys in Canada18 and Europe19 have shown the beneficial impact of specialized IBD nurses in the care of patients, although the exact depth of care and services remains unclear and there is a large variability of nursing profiles, roles and responsibilities with insufficient and heterogeneous presence in IBD units.

In Spain, the development of MDT for the management of IBD patients that include specialized nurses has been slowly implemented and geographically disperse. The Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU) developed a nationwide quality certification program for IBD units (named CUE), based on a comprehensive set of quality Indicators of structure, process, and outcomes.20 However, although the first quality indicator of the program was the presence of a nurse in the IBD unit, the defining criteria of the role and competences of this specialized nurse are still poorly established. Despite the cost-efficacy benefit of nursing consultation and the influence of nurses’ interventions for improving the patients’ quality of life demonstrated in different studies,15,21,22 there is a translational gap that prevents encouraging the existence or specialization of this advanced nursing role in healthcare centers. In fact, the heterogeneity of care models and their influence on the management of patients prompted the development of standards of healthcare quality for nursing management of IBD and the design of an evaluation tool based on these standards, the Nursing Care Quality in IBD Assessment (NCQ-IBD), which was published and validated in 2013.23 However, the experience using this questionnaire is limited to a study of IBD nursing care in Finland.24

Therefore, the present study was designed to provide a comprehensive nationwide assessment of the current status of nursing care for patients with IBD.

MethodsStudy design and populationThis was a nationwide observational and cross-sectional survey study, named The MAPEA project (“Modelo de Atención de Práctica EnfermeraAvanzada”, Advanced Nursing Practice Care Model), which was conducted between February 2021 and January 2022. The primary objective of the study was to determine the current situation of nursing care for patients with IBD throughout Spain to improve the quality, sustainability, and equity of care. Secondary objectives were as follows: (a) to assess professional competences, training level, and professional experience of nurses attending patients with IBD, as well as to identify their activities and roles played in their centers; (b) to evaluate the quality and variability of nursing care in patients with IBD; and (c) to analyze the provision of nursing human resources in IBD and the distribution of professional profiles over the country. To the end, all this information would serve not only as a basis for stimulating and implementing better nursing practices in the management of patients with IBD but also expand the IBD nursing workforce around the country.

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CEIC) of Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (code PR(AG)617/2019) of Barcelona (Spain), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study population and proceduresInclusion criteria were nurses involved in the care of patients with IBD, who were actively employed in public or private institutions throughout the country. Participation in the study was voluntary, anonymous, and unpaid. Protection of personal data according to Organic Law No. 3/2018, of 5 December 2018, was ensured.

The study procedures included a first step in which the working groups (Team-MAP) were created, followed by the development of the electronic case report form (eCRF) using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) web application, the selection of participants, and the coordination of data collection. A proposal to participate as coordinating and collaborative members of the Team-MAP was made at the annual meeting of the Spanish Nursing Working Group on IBD (“Grupo Enfermero de Trabajo en Enfermedad InflamatoriaIntestinal”, GETEII). The Team-MAP included 10 coordinating nurses, 2 for each of the five geographical areas, which were defined within the 17 autonomous communities of the country and supported by at least 5 nurses per area.

Target participants were identified through a multi-pronged approach: contacting nursing departments or regional nursing department councils (via postal or e-mail address), Head of Service (gastroenterology division), and members of the Spanish Gastroenterology Association (AEG), GETECCU, and GETEII. Those who agreed to take part in the study were provided the access link to the study questionnaire.

Study questionnaireThe selected tool to obtain information regarding the current status of IBD nursing care was the NCQ-IBD developed and validated by Torrejón et al.23 The NCQ-IBD questionnaire consists of 90 questions organized into five domains measuring the following aspects of nursing care in IBD: infrastructure (22 items), process (39 items), management and patient follow-up (12 items), training (13 items), and research (4 items). In addition, the NCQ-IBD sets a series of specific required items (n=16), which allows the classification of healthcare quality for nursing management of IBD into four categories from A to D, where category A corresponds to the highest quality nursing care model, and category D to the lowest quality model. At level A, all these 16 criteria need to be met. At level B, 13 specified criteria need to be met. At level C, 5 specified criteria need to be met. A description of the NCQ-IBD questionnaire and the corresponding quality categories is shown in Tables 1 and 2 of the Supplementary material, respectively. Moreover, all participants completed a set of questions regarding demographic data, professional experience, and working characteristics.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics of NCQ-IBD questionnaires that were fully completed are presented. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as mean and standard deviation (± SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) (25–75th percentile).

ResultsOf a total of 120 eligible participants who received the study questionnaire, responses from 92 of them were obtained (response rate 77.5%). These 92 participants provided data on demographics, professional experience, and working conditions. Data regarding quality of care in the management of patients with IBD (NCQ-IBD completed questionnaires) were provided by 71 centers.

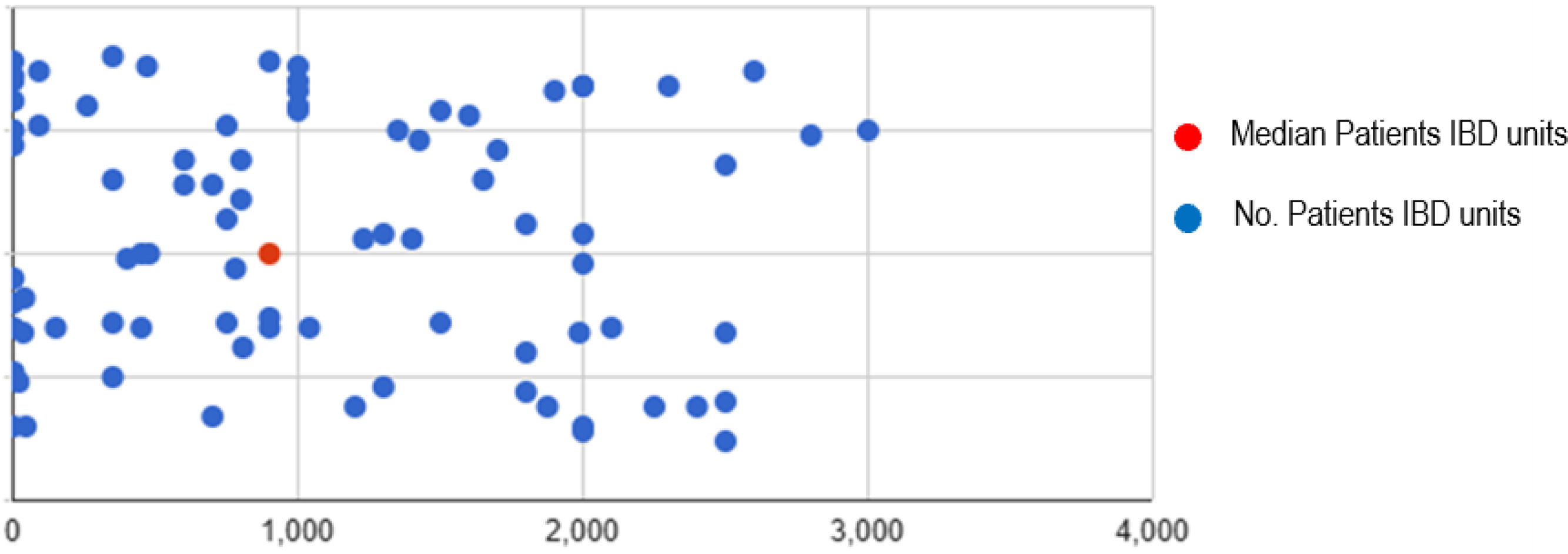

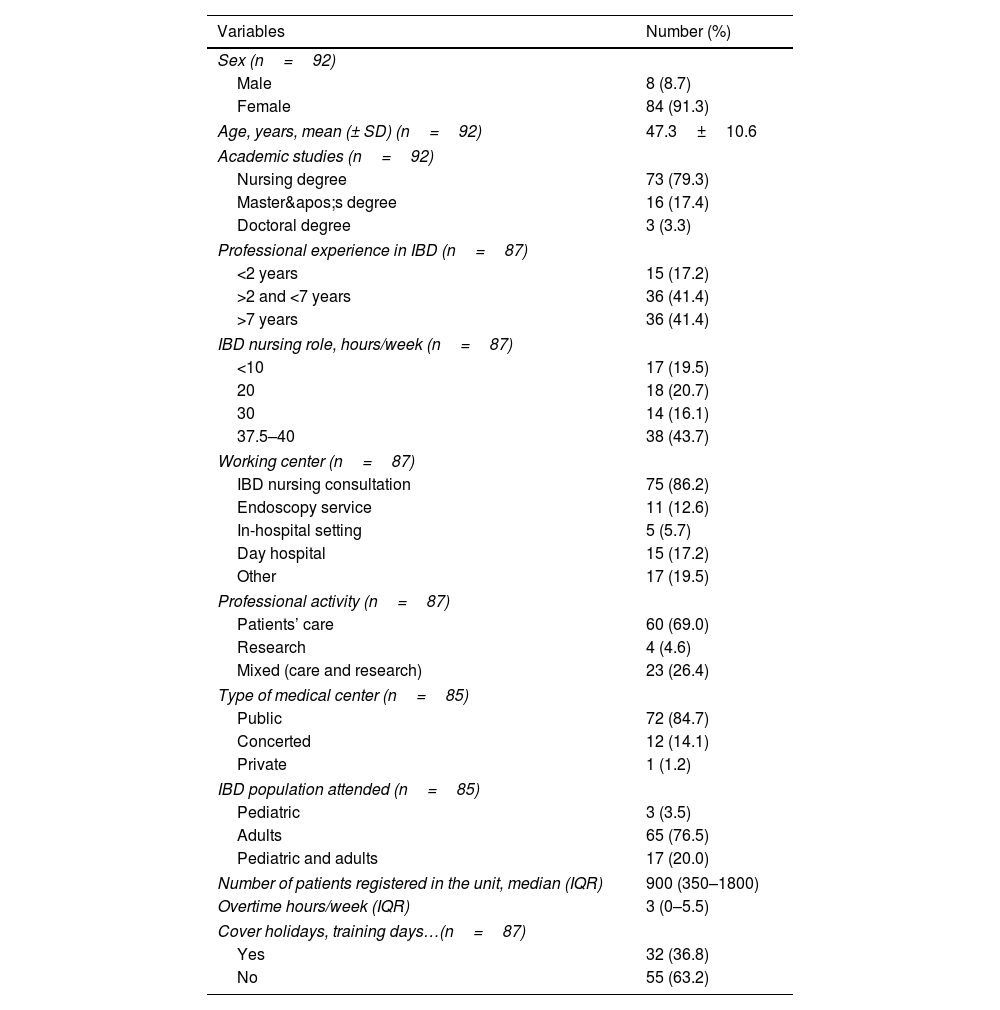

Study populationDemographic data included 91.3% of women and a mean age of 47.3±10.6 years. Most participants (79.3%) had a degree in nursing (RN) and 3.3% a doctorate title (PhD). Also 41% of participants reported more than 7 years of experience managing patients with IBD, and only 44% working full-time in IBD (between 37.5 and 40h/week). The majority of nurses (86.2%) worked in a monographic IBD unit from a public hospital (84.7%), attending adult patients (76.5%). The median number of IBD patients registered in the unit was 900 (IQR 350–1800). The general characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1.

Demographics and general characteristics of participants.

| Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex (n=92) | |

| Male | 8 (8.7) |

| Female | 84 (91.3) |

| Age, years, mean (± SD) (n=92) | 47.3±10.6 |

| Academic studies (n=92) | |

| Nursing degree | 73 (79.3) |

| Master's degree | 16 (17.4) |

| Doctoral degree | 3 (3.3) |

| Professional experience in IBD (n=87) | |

| <2 years | 15 (17.2) |

| >2 and <7 years | 36 (41.4) |

| >7 years | 36 (41.4) |

| IBD nursing role, hours/week (n=87) | |

| <10 | 17 (19.5) |

| 20 | 18 (20.7) |

| 30 | 14 (16.1) |

| 37.5–40 | 38 (43.7) |

| Working center (n=87) | |

| IBD nursing consultation | 75 (86.2) |

| Endoscopy service | 11 (12.6) |

| In-hospital setting | 5 (5.7) |

| Day hospital | 15 (17.2) |

| Other | 17 (19.5) |

| Professional activity (n=87) | |

| Patients’ care | 60 (69.0) |

| Research | 4 (4.6) |

| Mixed (care and research) | 23 (26.4) |

| Type of medical center (n=85) | |

| Public | 72 (84.7) |

| Concerted | 12 (14.1) |

| Private | 1 (1.2) |

| IBD population attended (n=85) | |

| Pediatric | 3 (3.5) |

| Adults | 65 (76.5) |

| Pediatric and adults | 17 (20.0) |

| Number of patients registered in the unit, median (IQR) | 900 (350–1800) |

| Overtime hours/week (IQR) | 3 (0–5.5) |

| Cover holidays, training days…(n=87) | |

| Yes | 32 (36.8) |

| No | 55 (63.2) |

SD: standard deviation; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IQR: interquartile range.

Regarding clinic infrastructure, affirmative responses were obtained in most items of this section of the NCQ-IBD, including having a space for IBD nursing consultation (85.9%), an own database (74.6%), direct telephone line (94.4%), own computer (94.4%), e-mail address (87.3%), use of electronic health records (EHRs) (96.8%), educational material for patients (90.1%). The area dedicated to IBD was indicated in the hospital map in only 19.7% of cases, and medical and nursing consultations had an identifying placard on the door in 49.3%.

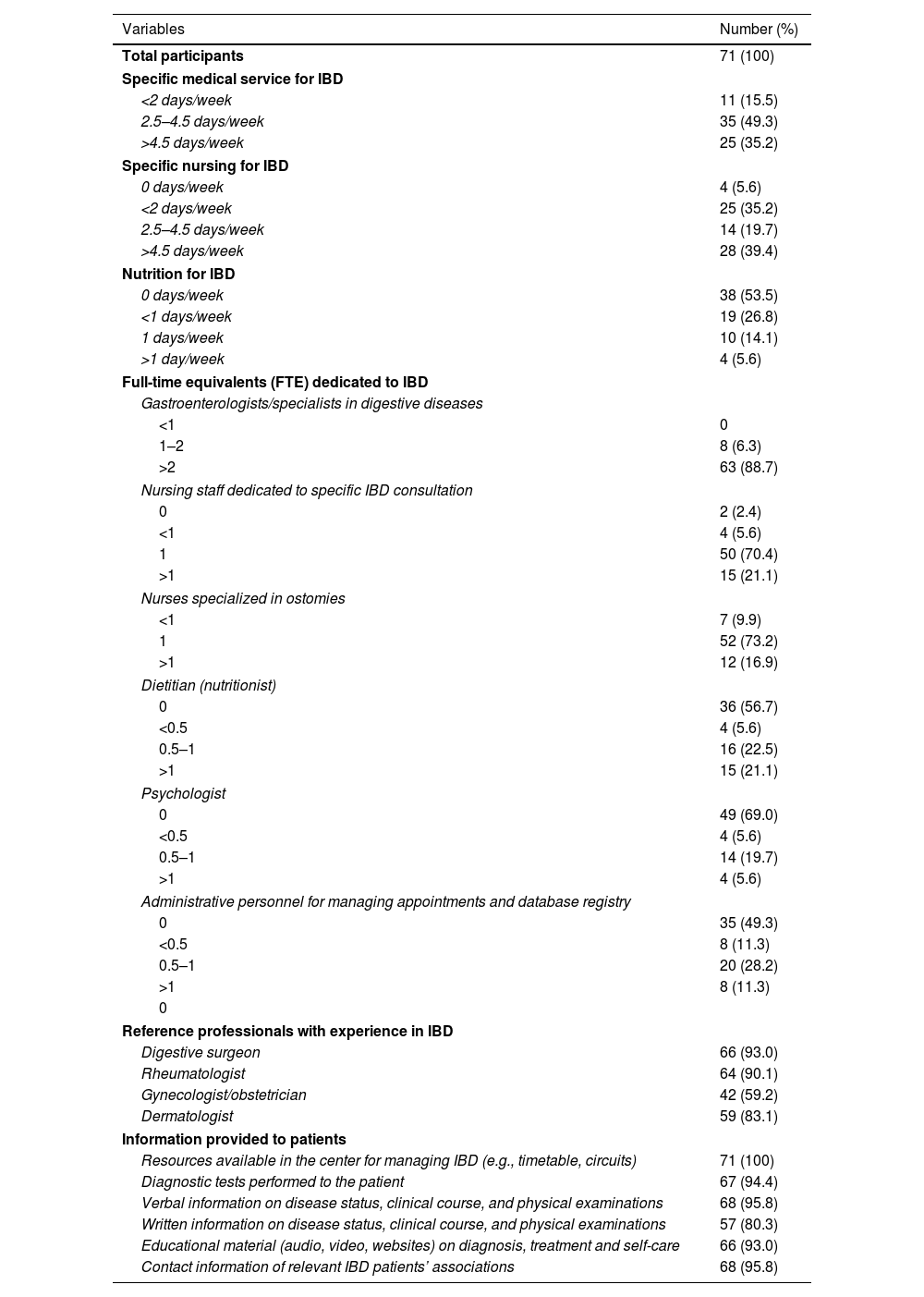

Services and human resources for IBDAs shown in Table 2, 60 out of 71 participants (84.5%) reported that a specific medical service for IBD was present for more than 2.5days/week. Regarding the presence of specific nursing IBD care 67 (94.4%) reported more than 2 days/week, being only 28 (39.4%) for more than 4.5 days/week. In relation to the number of hours considered full-time (FTE) dedicated to IBD by other team members, >2 gastroenterologists was reported in 63 (88.7%), and between 0.5 and 1 stoma therapist nurse in 64 (91%). The percentage of reference professionals with experience in IBD was very high especially for digestive surgeons (93%, n=66), rheumatologists (90%, n=64), dermatologists (83.1%, n=59) and gynecologists (59.2%, n=42). Specific IBD nutrition service was absent in 38 of cases (53.5%) and present for more than 1 days/week in only 4 (5.6%). No FTEs were reported for a high percentage of dietitians (56.7%), psychologists (69.0%), and administrative personnel for the management of IBD appointments and database registry (49.3%) (Table 2).

Services and human resources for the care of patients with IBD (NCQ-IBD questionnaire).

| Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 71 (100) |

| Specific medical service for IBD | |

| <2 days/week | 11 (15.5) |

| 2.5–4.5 days/week | 35 (49.3) |

| >4.5 days/week | 25 (35.2) |

| Specific nursing for IBD | |

| 0 days/week | 4 (5.6) |

| <2 days/week | 25 (35.2) |

| 2.5–4.5 days/week | 14 (19.7) |

| >4.5 days/week | 28 (39.4) |

| Nutrition for IBD | |

| 0 days/week | 38 (53.5) |

| <1 days/week | 19 (26.8) |

| 1 days/week | 10 (14.1) |

| >1 day/week | 4 (5.6) |

| Full-time equivalents (FTE) dedicated to IBD | |

| Gastroenterologists/specialists in digestive diseases | |

| <1 | 0 |

| 1–2 | 8 (6.3) |

| >2 | 63 (88.7) |

| Nursing staff dedicated to specific IBD consultation | |

| 0 | 2 (2.4) |

| <1 | 4 (5.6) |

| 1 | 50 (70.4) |

| >1 | 15 (21.1) |

| Nurses specialized in ostomies | |

| <1 | 7 (9.9) |

| 1 | 52 (73.2) |

| >1 | 12 (16.9) |

| Dietitian (nutritionist) | |

| 0 | 36 (56.7) |

| <0.5 | 4 (5.6) |

| 0.5–1 | 16 (22.5) |

| >1 | 15 (21.1) |

| Psychologist | |

| 0 | 49 (69.0) |

| <0.5 | 4 (5.6) |

| 0.5–1 | 14 (19.7) |

| >1 | 4 (5.6) |

| Administrative personnel for managing appointments and database registry | |

| 0 | 35 (49.3) |

| <0.5 | 8 (11.3) |

| 0.5–1 | 20 (28.2) |

| >1 | 8 (11.3) |

| 0 | |

| Reference professionals with experience in IBD | |

| Digestive surgeon | 66 (93.0) |

| Rheumatologist | 64 (90.1) |

| Gynecologist/obstetrician | 42 (59.2) |

| Dermatologist | 59 (83.1) |

| Information provided to patients | |

| Resources available in the center for managing IBD (e.g., timetable, circuits) | 71 (100) |

| Diagnostic tests performed to the patient | 67 (94.4) |

| Verbal information on disease status, clinical course, and physical examinations | 68 (95.8) |

| Written information on disease status, clinical course, and physical examinations | 57 (80.3) |

| Educational material (audio, video, websites) on diagnosis, treatment and self-care | 66 (93.0) |

| Contact information of relevant IBD patients’ associations | 68 (95.8) |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; FTE: full-time equivalent.

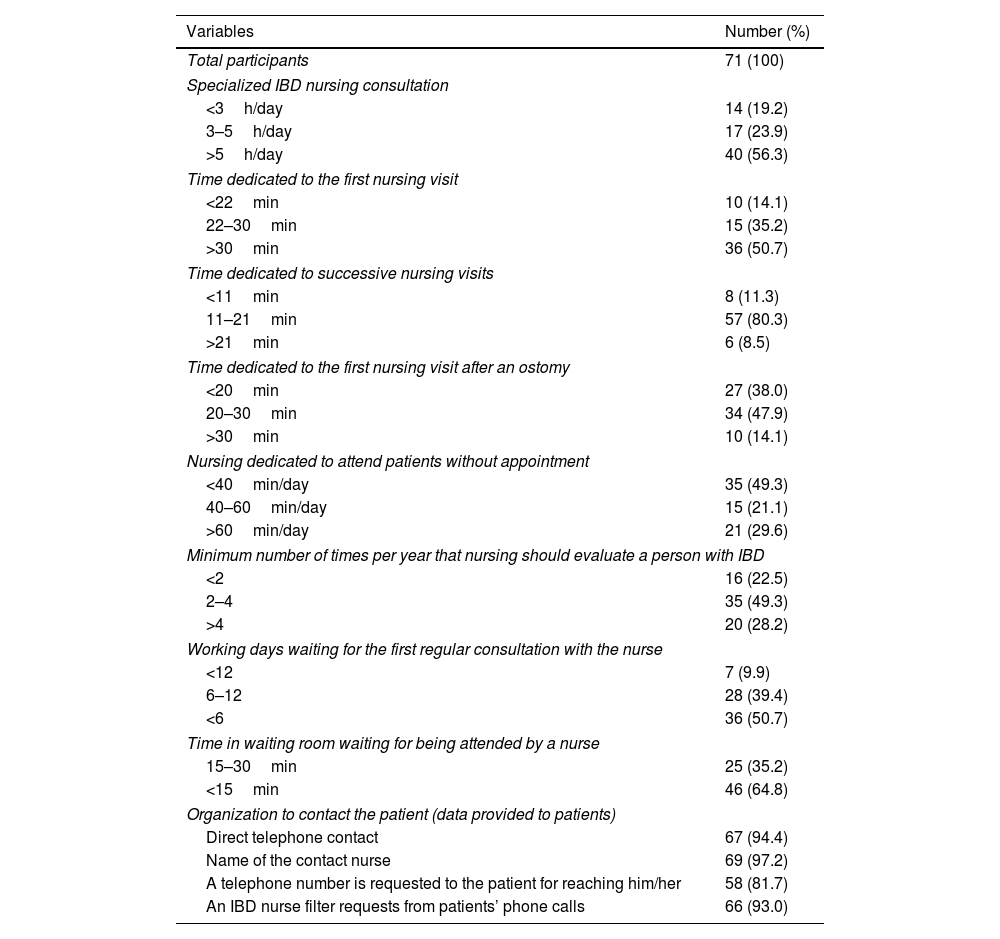

Data regarding the organization for the management of IBD are summarized in Table 3. A total of 56.3% of participants devoted more than 5h daily for IBD consultation, 50.7% more than 30min for the first IBD visit, and 80.3% between 11 and 21min for successive visits. However, for the first visit after an ostomy, 47.9% of participants reported between 20 and 30min. A patient with an IBD should be evaluated between 2 and 4 times a year according to 49.3% of participants. More than half of participants reported less than 6 days as the waiting days for a first regular consultation with the IBD nurse, and less than 15min in the waiting room for being attended. Data provided to patients with IBD, including telephone contacts accounted for more than 94% of responses. Also, an IBD nurse filter patients’ phone call requests in 93% of cases.

Organization for the management of IBD (NCQ-IBD questionnaire).

| Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 71 (100) |

| Specialized IBD nursing consultation | |

| <3h/day | 14 (19.2) |

| 3–5h/day | 17 (23.9) |

| >5h/day | 40 (56.3) |

| Time dedicated to the first nursing visit | |

| <22min | 10 (14.1) |

| 22–30min | 15 (35.2) |

| >30min | 36 (50.7) |

| Time dedicated to successive nursing visits | |

| <11min | 8 (11.3) |

| 11–21min | 57 (80.3) |

| >21min | 6 (8.5) |

| Time dedicated to the first nursing visit after an ostomy | |

| <20min | 27 (38.0) |

| 20–30min | 34 (47.9) |

| >30min | 10 (14.1) |

| Nursing dedicated to attend patients without appointment | |

| <40min/day | 35 (49.3) |

| 40–60min/day | 15 (21.1) |

| >60min/day | 21 (29.6) |

| Minimum number of times per year that nursing should evaluate a person with IBD | |

| <2 | 16 (22.5) |

| 2–4 | 35 (49.3) |

| >4 | 20 (28.2) |

| Working days waiting for the first regular consultation with the nurse | |

| <12 | 7 (9.9) |

| 6–12 | 28 (39.4) |

| <6 | 36 (50.7) |

| Time in waiting room waiting for being attended by a nurse | |

| 15–30min | 25 (35.2) |

| <15min | 46 (64.8) |

| Organization to contact the patient (data provided to patients) | |

| Direct telephone contact | 67 (94.4) |

| Name of the contact nurse | 69 (97.2) |

| A telephone number is requested to the patient for reaching him/her | 58 (81.7) |

| An IBD nurse filter requests from patients’ phone calls | 66 (93.0) |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; min: minutes.

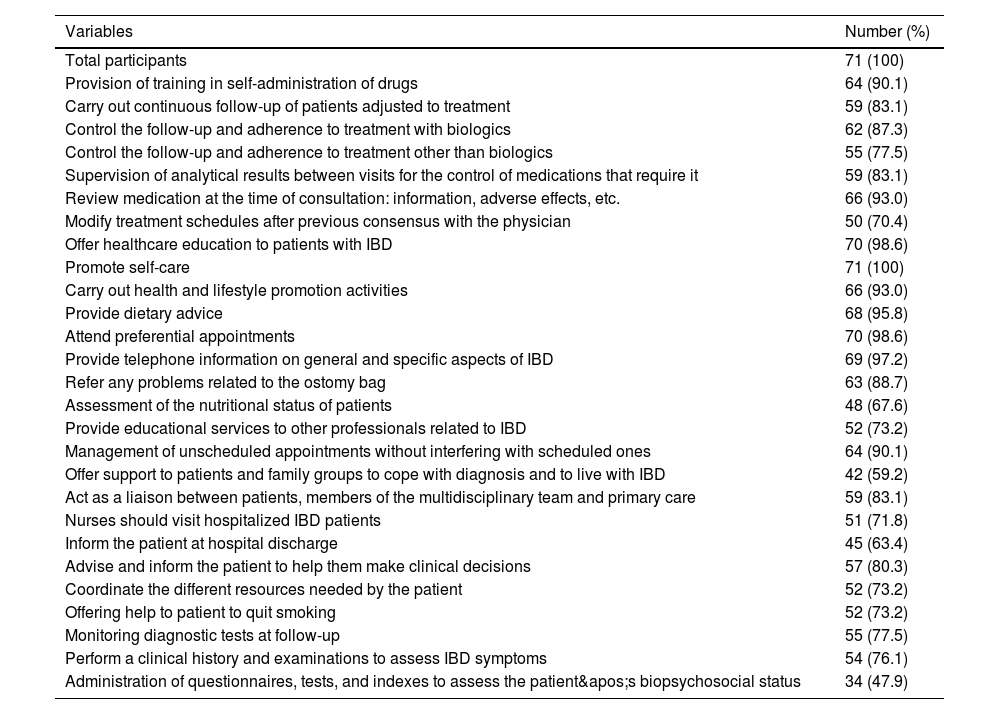

Of the list of 27 professional competencies identified for a specialized IBD nurse, 23 (85.2%) were met by more than 70% of participants (Table 4), particularly training in self-administration of drugs, review of the medication, offer healthcare education to patients with IBD, promoting self-care, provide dietary advice and telephone information on IBD, attendance of preferential appointments, and management of unscheduled appointments, which were met by more than 90% of participants. The administration of questionnaires, tests, and indexes to assess the patient's biopsychosocial status accounted for the lowest percentage (47.9%) followed by offering support to patients and family groups to cope with diagnosis and to live with IBD. In all items regarding information provided by IBD nurse to patients, the percentages were very high (around 95%) (Table 4).

Professional competencies of nurses in the management of IBD patients (NCQ-IBD questionnaire).

| Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 71 (100) |

| Provision of training in self-administration of drugs | 64 (90.1) |

| Carry out continuous follow-up of patients adjusted to treatment | 59 (83.1) |

| Control the follow-up and adherence to treatment with biologics | 62 (87.3) |

| Control the follow-up and adherence to treatment other than biologics | 55 (77.5) |

| Supervision of analytical results between visits for the control of medications that require it | 59 (83.1) |

| Review medication at the time of consultation: information, adverse effects, etc. | 66 (93.0) |

| Modify treatment schedules after previous consensus with the physician | 50 (70.4) |

| Offer healthcare education to patients with IBD | 70 (98.6) |

| Promote self-care | 71 (100) |

| Carry out health and lifestyle promotion activities | 66 (93.0) |

| Provide dietary advice | 68 (95.8) |

| Attend preferential appointments | 70 (98.6) |

| Provide telephone information on general and specific aspects of IBD | 69 (97.2) |

| Refer any problems related to the ostomy bag | 63 (88.7) |

| Assessment of the nutritional status of patients | 48 (67.6) |

| Provide educational services to other professionals related to IBD | 52 (73.2) |

| Management of unscheduled appointments without interfering with scheduled ones | 64 (90.1) |

| Offer support to patients and family groups to cope with diagnosis and to live with IBD | 42 (59.2) |

| Act as a liaison between patients, members of the multidisciplinary team and primary care | 59 (83.1) |

| Nurses should visit hospitalized IBD patients | 51 (71.8) |

| Inform the patient at hospital discharge | 45 (63.4) |

| Advise and inform the patient to help them make clinical decisions | 57 (80.3) |

| Coordinate the different resources needed by the patient | 52 (73.2) |

| Offering help to patient to quit smoking | 52 (73.2) |

| Monitoring diagnostic tests at follow-up | 55 (77.5) |

| Perform a clinical history and examinations to assess IBD symptoms | 54 (76.1) |

| Administration of questionnaires, tests, and indexes to assess the patient's biopsychosocial status | 34 (47.9) |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

In relation to the quality aspects, 88.7% of nurses used clinical practice guidelines or protocols for the management of patients and 74.6% applied scales for assessing anxiety and depression. However, only 18.8% and 25.4% responders evaluated classification and activity indexes in IBD, respectively.

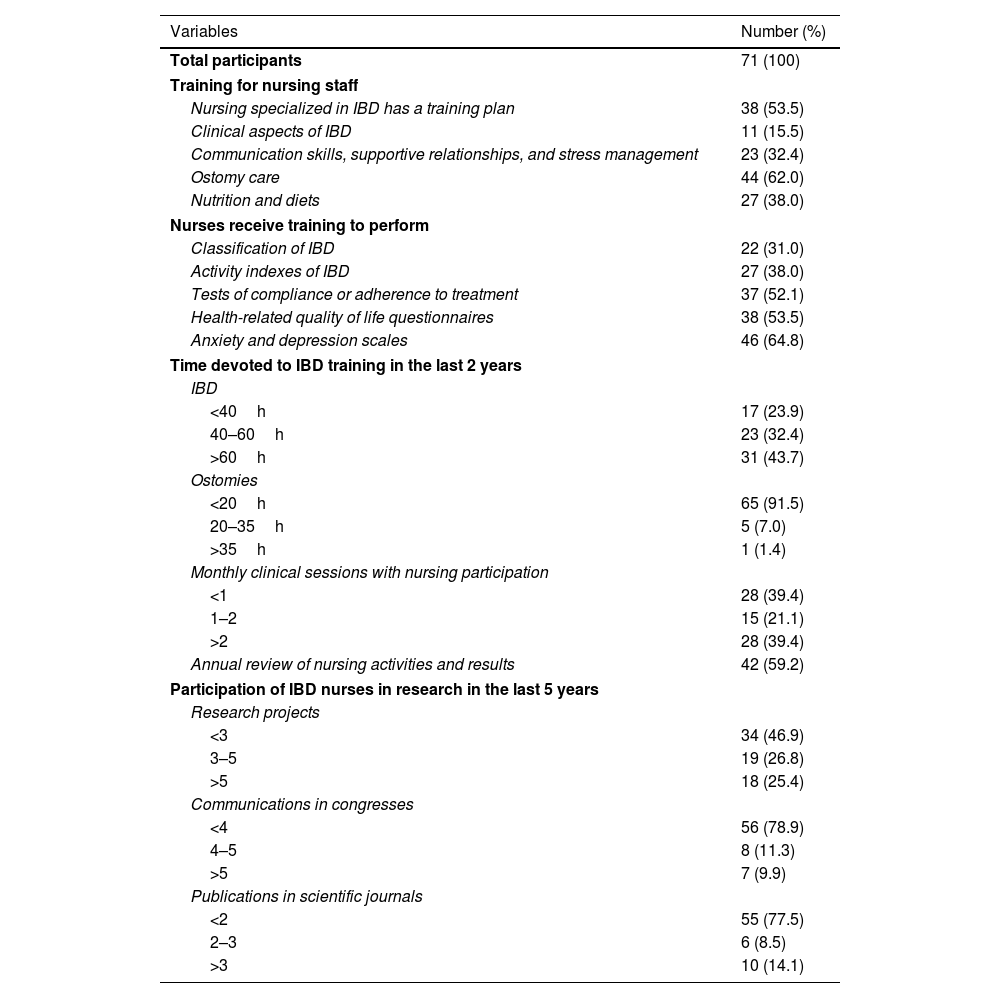

Training and research activitiesThe results obtained in the section of the NCQ-IBD questionnaire assessing training activities and research if IBD nurses are summarized in Table 5. Only 53.5% of participants reported to have available a training plan in IBD and 62% had a training program on ostomy care. Training to perform medication adherence tests as well as to administer health-related quality of life and anxiety/depression questionnaires was reported by about half of participants. In the last 2 years, the number of hours devoted to IBD training was higher than 60 in 43.7% of participants, but 91.5% recognized less than 20h for training in ostomy care. The participation in monthly clinical sessions was also limited, with 21.1% of nurses participating in 1 or 2 sessions. Also, research activities in the last 5 years included more than five research projects in 25.4% of nurses, more than five communications in congresses in 9.9%, and more than three published articles in 14.1%.

Training and research activities of IBD nurses (NCQ-IBD questionnaire).

| Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 71 (100) |

| Training for nursing staff | |

| Nursing specialized in IBD has a training plan | 38 (53.5) |

| Clinical aspects of IBD | 11 (15.5) |

| Communication skills, supportive relationships, and stress management | 23 (32.4) |

| Ostomy care | 44 (62.0) |

| Nutrition and diets | 27 (38.0) |

| Nurses receive training to perform | |

| Classification of IBD | 22 (31.0) |

| Activity indexes of IBD | 27 (38.0) |

| Tests of compliance or adherence to treatment | 37 (52.1) |

| Health-related quality of life questionnaires | 38 (53.5) |

| Anxiety and depression scales | 46 (64.8) |

| Time devoted to IBD training in the last 2 years | |

| IBD | |

| <40h | 17 (23.9) |

| 40–60h | 23 (32.4) |

| >60h | 31 (43.7) |

| Ostomies | |

| <20h | 65 (91.5) |

| 20–35h | 5 (7.0) |

| >35h | 1 (1.4) |

| Monthly clinical sessions with nursing participation | |

| <1 | 28 (39.4) |

| 1–2 | 15 (21.1) |

| >2 | 28 (39.4) |

| Annual review of nursing activities and results | 42 (59.2) |

| Participation of IBD nurses in research in the last 5 years | |

| Research projects | |

| <3 | 34 (46.9) |

| 3–5 | 19 (26.8) |

| >5 | 18 (25.4) |

| Communications in congresses | |

| <4 | 56 (78.9) |

| 4–5 | 8 (11.3) |

| >5 | 7 (9.9) |

| Publications in scientific journals | |

| <2 | 55 (77.5) |

| 2–3 | 6 (8.5) |

| >3 | 10 (14.1) |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

Finally, healthcare quality for nursing management of IBD was classified into category A in 2 (2.8%) cases, category B in 53 (74.6%), and category C in 16 (22.5%).

DiscussionIdentification of areas of improvement is not only highly relevant for patient care and outcomes, but also contributes to reduce variability in clinical practice. The profile of participants was a middle-aged female, with more than 2 years of experience in IBD, working in a high-volume IBD unit for adults belonging to public centers, and primarily dedicated to the patient's care. These professional characteristics enhance the reliability of results obtained using the NCQ-IBD questionnaire.

Category B of the NCQ-IBD healthcare quality for nursing management of IBD was achieved in 74.6%. The highest A category was achieved in only 2.8% of cases. This could be explained by the high nurse caseload that prevented to achieve the requirement of less than 6 working days waiting for the first regular consultation with the IBD nurse (item #29). In the previous study of certification of inflammatory bowel disease units by GETECCU, among the 53 units already audited, 31 (58.5%) achieved the certification of excellence.20 In this study, the waiting time for the first consultation with a specialized nurse was not defined, which could make us to reconsider that the weight of item #29 might be a limiting feature in the global assessment of the quality of nursing management in IBD. The units were well-equipped with a direct telephone helpline, e-mail access, EHRs, educational materials for patients, as well as computer and electronic database facilities, all housed in their own clinical space. These quality indicators have been also identified in the GETECCU certification program.20 However, the location of the IBD units on the hospital maps and the signage on nursing consultation doors, which were indicated in only 19.7% and 49.3% of cases, respectively, are areas that need improvement.

IBD should be ideally managed in the setting of a multidisciplinary team25 with specialized nurses playing an important role within this team. To achieve optimum proactive management of care, it has been recommended a caseload of 2.5 FTE IBD specialist nurse per 250,000 patient populations, which gives a static caseload of 500 per FTE.26 As shown in Fig. 1, our current patients/IBD nurses ratio is insufficient and much lower than recommended standards. This insufficient ratio is a main factor for the impossibility to achieve less than 6 days waiting time for the first consultation (item #29), and is also related to the limited presence of full-time nurses. Although 70% of units had an IBD nurse, unfortunately 40% worked two days a week and only 39% full-time. These data indicate some discrepancy with findings in Table 2, but might be explained due to participants’ personal interpretations of FTE meaning. The sum of factors such as the limited presence of full-time nurses, the high patients/nurses ratio, and the lack of administrative support may have a relationship with the number of overtime hours that nurses have to work and coverage for vacations and sick leave. In this respect, it has been shown that nurse-led telephone services are very effective for resolution of a wide range of patient queries in IBD.27 In an update of the quality criteria for IBD care units from a multi-stakeholder perspective and using multicriteria decision analysis, the presence of IBD nurses, gastroenterologists, experienced surgeons, endoscopists, and radiologists in the IBD multidisciplinary team was considered the most important structural aspect of an IBD comprehensive care unit.28 The CUE program has promoted and facilitated the inclusion of specialized nurses in IBD units. However, the lack of a definite minimum number of working hours in its standard, stating only that a nurse must be present in the MDT, results in significant heterogeneity and inequity in IBD nursing care across the country. On the other hand, despite IBD nurses serving as the primary point of contact between patients and healthcare services, the IBD nurse role may frequently remain uncovered during holidays or sick leaves.24,26,29

If we focus on the availability of nutrition services and dietitians this was surprisingly low, despite the well-known importance of nutritional aspects and dietary recommendations in the management of IBD.30 A high percentage of participants reported specialists available for referrals, but the presence of psychologists was unexpectedly very low, although more than 70% of participants used scales for assessing anxiety/depression and more than 50% reported training in adherence to medication, quality of life instruments, and anxiety/depression questionnaires.

Two quality indicators including IBD classification scores and activity indexes were evaluated by a markedly low percentage of participants (19% and 25%, respectively) as compared to 89% who reported the use of clinical practice guidelines or protocols in the management of patients with IBD. These results highlight the need to incorporate these tools in clinical practice to help IBD-specialized nurses assess the activity and severity of the patients’ condition. In a cross-sectional survey study using the same NCQ-IBD questionnaire and conducted in 27 tertiary IBD outpatient clinics in Finland, a significant lack in the usage of structured tools such as IBD activity indexes was also documented.24 These findings underscore the need to incorporate structured clinical tools into routine nursing practice and to reflect on the factors limiting their implementation. Time constraints, insufficient training, lack of standardized protocols, and the non-integration of indexes into electronic health records, are frequently reported barriers in diverse healthcare settings.24–31Addressing these gaps requires not only institutional support to provide protected time, but training and digital tools that facilitate it's systematic utilization. At the same time, IBD nurses must actively prioritize their use to support clinical decisions with measurable, standardized indicators. Strengthening this practice will allow for more precise patient monitoring, enhance the comparability of outcomes, and contribute to the visibility and professional recognition of nursing care in IBD.

Medication management and patient education on medication self-administration are prominent features in IBD. All participants in our study educate their patients on medication self-administration and were actively involved in crucial aspects of the IBD patients’ care, including modification of treatment based on physician's recommendations, review of medication at the time of consultation, and follow-up and control of compliance with treatment. Other important activities, such as assessment of nutritional status and offering support and understanding to patients and family groups to cope with diagnosis and to live with IBD were mentioned by around 60% of participants. Accordingly, IBD nurses may play a relevant role for counseling and improving the dietary patterns of people with IBD.

Nursing training and research in IBD was not very active according to results of the present survey. It would be important to potentiate training activities in comprehensive clinical aspects of IBD as only 15.5% of participants reported having being received this kind of training, as well as communication skills for supporting the patients and managing stress. Over the last three years a university-level master's degree (60 ECTS) specifically dedicated to IBD nursing has been established in Spain.32 This program, promoted by GETEII, offers a more structured and comprehensive training pathway for nurses specializing in this area. The expanding availability of such initiatives foresees to facilitate future efforts toward specialized competencies, formal recognition and accreditation of the IBD nursing role. The experience in research was also limited, with low percentages of participants taking part in research projects, presentations at scientific meetings, and publications in journals during the past 5 years. This may be explained by the fact that clinical work of IBD nursing is usually emphasized over research. In a survey carried out in the United Kingdom among 274 nurses involved in the care of patients with CD, 28% described other clinical responsibilities within their role, including more general gastroenterology, nurse endoscopist, ward working and research, although specific data on research was not reported.26

Limitations of the study include the reduced number of participants. Despite utilizing the 2018 national hospital registry (listing 804 hospitals) and undertaking extensive outreach efforts through collaborative groups to identify eligible nurses (beyond accredited IBD Units), recruiting a larger sample proved difficult. This process often required navigating through complex hospital administrative structures, sometimes starting with patient information services to ultimately reaching the Head nurse.

It should be noted that at the time of the study, only 53 units were accredited by GETECCU, whereas the study sample comprised 71 centers. This extensive recruitment strategy likely mitigate the risk of significant selection bias, enhancing the representativeness of the sample and capturing a broader spectrum of IBD nurses beyond only those in highly developed or accredited units.

Another reason may be explained by the need to complete the NCQ-IBD instrument, which a large 90-item questionnaire during the daily high workload. However, an important reason of the limited study population may be the shortage of specialized IBD nurses around the country, although a total of 53 IBD units achieved quality certification by the GETECCU. The scarcity of IBD nurse specialists has been emphasized in other studies.33,34

The main strength of this study it is being the first nationwide survey to assess the quality of nursing care for IBD patients. The findings provide valuable baseline knowledge on the current state of specialized IBD nursing, allowing for the identification of areas for improvement and serving as a reference for future research.

In this context, research agenda focuses on developing a professional practice framework for nurses involved in IBD care. This will enable nurses, regardless of where they work, to provide consistent care to all IBD patients around the territory. Continuing this approach, it raises the need for developing measurable, standardized indicators for registering IBD nursing interventions and its quantifiable outcomes. This framework could help ensure these indicators are clearly defined.

ConclusionsThis survey study, conducted among nurses working in IBD units across Spain using a validated instrument, provides data on various aspects regarding the characteristics and activities of IBD nurses. The overall quality of care, rated across four categories was scored as B (high) in 75% of participants. The development of IBD nursing activities was highly satisfactory, encompassing patient management, adherence to clinical practice guidelines or protocols, medication evaluation, and education on medication self-administration. However, specific areas for improvement identified in the study included better visibility of the IBD unit on the hospital map, the signage on consultation room doors, administrative support, holiday coverage, encouraging research and especially, increasing the ratio of nurses working full-time.

Ethical approvalThe study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CEIC) of Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (code: PR(AG)617/2020), Barcelona, Spain.

FundingNo funding has been received for this study.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

The authors are grateful to all nurses who participated in the study. They also thank Marta Pulido, MD, PhD, for editing the manuscript and editorial assistance.

Francisca Murciano Gonzalo, Ester Navarro Correal, Adriana Rivera Sequeiros, and Diana Muñoz Gómez (coordinators). EPA Team: Elena Sánchez Pastor, Mercedes Cañas Gil, Laura Marín Sánchez, Pilar Corsino Roche, Noelia Cano Sanz, and Ana María López Calleja. Maps Team: Ma Ángeles Marinero Muñoz, Rosario Medina Medina, José María Martín, Cristina Mira, Carmina Ascensio Muñoz, Jorge Sergio Medina Chico, Salvadora Benito Palma, Ma Luisa Cabanillas Navarro, Ma Ángeles Castro Mariscal, Rosa Ma Jurado Monroy, Jesús Noci Belda, Judit Orobitg Bernades, Ma Soledad Serrano Redondo, Ana María Duro Martínez, Ma Isabel Mateos Hernández, Emilia Fernández, Ma del Mar Aller Zamanillo, Ma del Mar Sánchez Calabuig, Arantxa Ibarz, and Zahira Pérez.