Crohn’s disease consists on a complex condition where, despite most patients initially present with an inflammatory behavior, a significant proportion develop complicated lesions such as strictures, fistulas, abscesses, or even perforations. These lesions progressively increase over time and are associated with a higher risk of surgery and hospitalization. Despite significant advances in their management after the introduction of biological therapies, particularly anti-TNF agents, these complications continue to pose challenges for the multiple professionals involved in their care.

Fistulas that do not involve the perianal region (entero-enteric, entero-urinary, or entero-cutaneous) require a multidisciplinary strategy that combines medical, interventional, and surgical approaches. Their treatment ranges from general supportive measures to the use of antibiotics or, frequently, advanced therapies. Nevertheless, in cases of certain septic complications or those refractory to medical treatment, percutaneous drainage or surgical intervention remains essential.

Although these lesions have a significant impact, evidence regarding the best strategies in this context, as well as the efficacy and safety of different therapies in these patients, remains limited. This is highlighted by the absence of specific recommendations in current guidelines. The objective of this document is to provide a comprehensive overview of non-perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease, addressing its epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic aspects from a multidisciplinary perspective.

La enfermedad de Crohn representa una enfermedad compleja en la que, a pesar de que la mayoría de pacientes presenta inicialmente un patrón inflamatorio, una proporción importante desarrolla complicaciones como estenosis, fístulas o abscesos, o incluso perforaciones. Estas lesiones aumentan progresivamente a lo largo del tiempo y están asociadas a un riesgo más elevado de cirugía y hospitalización. A pesar de que su manejo ha mejorado considerablemente con la introducción de terapias biológicas, especialmente los agentes anti-TNF, éstas siguen constituyendo un reto para los diferentes profesionales involucrados en su manejo.

Las fístulas que no afectan a la región perianal (entero-entéricas, entero-urinarias o entero-cutáneas) requieren una estrategia multidisciplinar, combinando un enfoque tanto médico como intervencionista o quirúrgico. Su tratamiento comprende desde la medidas de soporte generales hasta el uso de antibioterapia o, con relativa frecuencia, terapias avanzadas. A pesar de esto, en casos de ciertas complicaciones sépticas o refractarias al tratamiento médico, el drenaje percutáneo o tratamiento quirúrgico siguen siendo esencial en su manejo.

Aunque estas lesiones tienen un impacto importante, la evidencia sobre las mejores estrategias en este contexto, así como la eficacia y seguridad de las diferentes terapias en estos pacientes, sigue siendo limitada, destacando la ausencia de recomendaciones específicas en las guías actuales. Este documento tiene como objetivo proporcionar una visión integral sobre la enfermedad de Crohn fistulizante no perianal, abordando aspectos epidemiológicos, clínicos y terapéuticos desde una perspectiva multidisciplinar.

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease that presents significant challenges both in terms of diagnosis and management, as it is relatively frequently associated with complicated lesions that result from progressively accumulating intestinal damage.1 Although at diagnosis most patients have an inflammatory pattern, according to the Montreal classification,2 signs of bowel damage can already be detected in an estimated four out of ten patients in the first few months after diagnosis, and this is related to a higher risk of surgery and hospital admission in the long-term.3 The prevalence of these disease-related complications increases gradually over time, although the highest rates were reported before the availability of biological drugs.4,5

Complications in penetrating CD include different lesions, such as fistulas, abscesses and intestinal perforation. In the case of fistulas, these are defined as tracts that connect two intestinal loops (enteroenteric fistula), a loop with other organs or viscera (enterourinary fistula) or even with the skin (enterocutaneous fistula). The complexity of CD combined with the classification of its behaviour make it difficult to assess the progression of the disease, taking into account that up to 85% of penetrating intra-abdominal lesions coexist with stricturing.6

The availability of an increasing number of advanced therapies (both biologic agents and small molecules) has led to improved disease control and even a reduction in the rate of patients developing penetrating disease, especially thanks to tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors.7 Despite this, a significant number of patients still develop these lesions, in many cases requiring some type of surgical intervention or procedure for drainage of collections,8 although all of these techniques have also been subject to major advances in recent years. As part of the current approach to medical treatment in these cases, it is generally considered that patients with complicated CD should be treated with a more intensive strategy than those with uncomplicated disease. However, evidence of the efficacy and safety of medical management in these cases remains limited. As an example, this is reflected in the lack of recommendations on the subject in the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines for the treatment of CD.9 The aim of this document is therefore to provide an updated overview of non-perianal fistulising disease, including both epidemiological and clinical aspects and management from a medical, interventional or surgical perspective, as they are all closely related in this scenario.

Epidemiology of fistulising diseaseOne of the first descriptions of the disease by Crohn back in 1941 stated that more than half of the patients had fistulas.10 This has changed dramatically, as fistulising behaviour is currently described in 7% of newly diagnosed patients in Spain,11 but the rate seems to vary greatly depending on multiple factors, such as the historical moment analysed (pre- or post-biologic era), the population in which it is evaluated and disease duration.

The incidence of the fistulising pattern has also been affected by the classification used in different studies. The Vienna classification categorised the behaviour of CD into three types: penetrating, stricturing or "non-fistulising non-penetrating," including perianal disease in the first category.12 This classification was updated in 2005 with the Montreal classification, from which point onward luminal fistulising disease and perianal disease were differentiated into two distinct categories.2 Taking these aspects into account, one of the first population-based studies of the Olmsted cohort (Minnesota, USA) was published in 2002, which described the natural history of CD using the Vienna classification. In it, Schwartz et al.4 reported a 35% incidence of fistulas during the period from 1970 to 1995, with the majority of these fistulas being perianal (54%), 24% enteroenteric, and 9% rectovaginal or anovaginal. The cumulative incidence of fistulas in this cohort was estimated at 33% at 10 years, and 50% at 20 years from diagnosis.4 Excluding perianal disease (according to the Montreal classification), subsequent studies have reported an incidence of the fistulising pattern in the range of 3% to 23% at the time of diagnosis.5,8,13–17 In contrast to the most recent data from Spain or other countries in our region, other reference epidemiological cohorts, such as that of the Faroe Islands, which stand out for their progressive increase in incidence, have not reported any cases of fistulising disease at diagnosis,14 highlighting the importance of contextualising epidemiological data when characterising the disease. Beyond the formation of fistulas and abscesses, the risk of perforation has also been reported within the fistulising phenotype,18,19 with a cumulative incidence of 3% and 18% at five years after diagnosis.20

In data from the Olmsted cohort from 1970 to 2004, already using the Montreal classification, it was reported that 14% of patients at diagnosis showed a penetrating pattern, while in more recent cohorts, such as the Epi-IBD, the figure was 8%.5,8 The rate increases progressively in all the cohorts, being even higher in patients with stricturing disease (11%) than in those with an inflammatory pattern (4%).8 In the longer term, although with data obtained during the prebiological era, it has been estimated that the proportion of patients with fistulising disease may increase to 32% after 30 years.5 Although initial studies did not find significant changes in the development of fistulising disease with the use of early immunosuppressants,20,21 the incorporation of different advanced therapies, as well as their use at an earlier stage, have changed the natural history of CD. Based on the most recent data, we might expect that early use of biological therapies, especially TNF inhibitors, could alter the disease course and prevent such progression, but the evidence is still limited.7,22,23

The age at diagnosis of CD is one of the factors related to an increased risk of developing a fistulising phenotype, with the risk higher in patients diagnosed before the age of 4020,24 and increasing the younger they were.5 Some environmental factors, such as smoking, have also been linked to the development of fistulas,25–27 while physical activity could have a protective effect.25 Additionally, inflammatory bowel disease activity in the form of flare-ups26 or the presence of deep ulcers in colonic disease28 have been linked to an increased risk of having a fistulising pattern. In terms of disease location, some studies have related ileal involvement with the development of fistulas,17,29 while others have found no differences.30 An increased risk has also been described in patients positive for anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) at any time in the natural history of the disease, including where it was detected before diagnosis.17,31,32 This phenotype has also been linked to certain mutations in the NOD2 gene. However, this finding remains subject to debate.33–35 We have to take into account the complexity of the genetic model, the large number of possible candidate genes and the environmental factors which can modulate their effect. More recent studies have also found a different risk of developing a fistulising phenotype depending on ethnicity and migration factors, especially in populations originating from South Asia and migrating to Western countries.36 However, in the registry from the Estudio Nacional en Enfermedad Inflamatoria Intestinal sobre Determinantes Genéticos y Ambientales (ENEIDA) [Spanish National Study on the Genetic and Environmental Determinants of Inflammatory Bowel Disease], patients born outside of Spain have been found to have a lower rate of stricturing complications, although no differences have been detected in the risk of penetrating disease.37

In addition to all these aspects, due to their more aggressive behaviour, penetrating complications mean a higher risk of admission to hospital8 surgery13,15,16,24,29 and disease recurrence after surgery.38 These are highly relevant aspects that need to be taken into account when planning the comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment strategy for these patients, and which we will be covering in this document.

Clinical characteristicsSymptomsIntra-abdominal fistulas develop as a result of the transmural progression of the inflammatory process, with two types: internal and external. Internal fistulas connect two viscera (including the mesentery) to each other, while external or enterocutaneous fistulas connect a viscera to the skin. External fistulas are rare (prevalence of 0.3%),39,40 but can develop both spontaneously (on an area of intact skin) or in the bed of a surgical wound (frequently associated with dehiscence of an anastomosis), and tend to have a significant negative impact on both the patient's quality of life and the overall management of the disease. Table 1 shows a summary of the different types of fistulas. The clinical presentation will be determined by the viscera involved and whether there are associated phlegmons or abscesses,41 which we review below.

- a

Enteroenteric fistulas

Enteroenteric fistulas connecting adjacent segments tend to be asymptomatic and do not usually affect the patient's nutritional status. However, fistulas that connect proximal sections of the small intestine with more distal sections tend to have a higher output and generate a "by-pass", leading to a greater risk of diarrhoea, weight loss, hypoalbuminaemia and/or malabsorption.42

Ileoileal and ileocolic fistulas usually cause few symptoms or are even asymptomatic. However, ileosigmoid fistulas (frequently with the sigmoid colon free of inflammatory activity), cologastric or coloduodenal fistulas can cause malnutrition and weight loss, as well as diarrhoea and/or vomiting.41 In cologastric cases, which usually affect the distal transverse colon and involve the greater curvature of the stomach, patients may be asymptomatic or have diarrhoea, nausea, halitosis, weight loss, malnutrition and/or borborygmi, even resulting in dehydration and steatorrhoea in some cases. Faecal vomiting is virtually pathognomonic, but only occurs in one-third of patients.43 In the physical examination we may also find a mass effect.44,45 Coloduodenal fistulas usually affect the proximal transverse colon and the third portion of the duodenum,46 and tend to be asymptomatic or associated with nonspecific symptoms such as diarrhoea and abdominal pain, or more specific symptoms such as faecal vomiting and signs of malabsorption and malnutrition. Again, faecal vomiting is very specific, but only occurs in 2% of patients.

- b

Enterourinary fistulas

Within this type of fistula, enterovesical fistulas are the most common (around 90%), followed by urethral (6%) and ureteral (1%).47 Enterovesical fistulas originate in the ileum in 64–80% of cases and are more common in males (females are more protected by the barrier between the uterus and the vagina) and in the right side of the abdomen.48,49 The most common symptoms are pneumaturia (68–77%), dysuria (64%), faecaluria (28–50%), increased urinary frequency (45%), recurrent urinary tract infections (32–45%), abdominal pain (33%) and leakage of urine through the rectum (9%).47–51

- c

Enterogenital fistulas

Rectovaginal fistulas are the most common within this group, and usually originate from the lower portion of the rectum to the lower half of the vagina, near the introitus, or from the middle portion to the upper half of the vagina. The usual symptoms of rectovaginal and anovaginal fistulas are the passage of faeces or gas through the vagina, with foul-smelling and sometimes purulent secretions, or dyspareunia,52 although up to 20% can be asymptomatic.

Enterouterine or enterosalpingeal fistulas are rare; they may cause symptoms similar to those of rectovaginal or anovaginal fistulas, but in other cases the symptoms are completely nonspecific, such as abdominal pain and malaise, so a high level of suspicion is required for diagnosis.

- d

External fistulas

External fistulas usually originate in ileal or colic segments (about 67% and 23% respectively), and two-thirds of patients may show signs of luminal activity or associated intra-abdominal abscesses.53 Approximately 51% are spontaneous and 49% postoperative, with the spontaneous having a better prognosis in terms of fistula closure.53 Characteristic of tracts of this type is the passage of intestinal contents to the surface of the skin, giving rise to associated inflammatory changes, and in situations of high output leaks, they can cause fluid and electrolyte imbalance, malabsorption and dehydration.54

- e

Inflammatory mass and abscess

Phlegmon and abscess are complications in which we would expect to find an associated fistula, although it cannot always be identified by cross-sectional imaging tests. Both usually appear adjacent to a bowel segment with inflammatory activity, and the most common location is the right side of the abdomen due to its relationship with the ileum. They should also be considered in patients with recent surgery,55 and have been associated with both internal and external fistulas.56 In a third of patients, they produce typical symptoms of abdominal pain, fever, chills and/or a palpable mass. Symptoms can differ depending on the location, as in abscesses affecting the psoas muscle, which can lead to pain in the flank, hip, thigh or knee on the same side or even difficulty walking.57 However, the vast majority of abscesses and phlegmons develop without associated symptoms (except for those derived from luminal activity) or with nonspecific symptoms; hence the great importance of maintaining a high degree of suspicion and performing the necessary tests for diagnosis. There are certain clinical and analytical characteristics in these patients which should raise our level of suspicion, such as the presence of anaemia, leucocytosis, increased C- reactive protein (CRP), increased urea, young age, associated perianal disease and active biological therapy,58,59 while the influence of corticosteroids is still subject to debate.58,60 Of all of the above, elevated CRP is the one most closely related to the likelihood of developing an intra-abdominal abscess.

Types and classification of fistulas.

| Internal fistulas | External fistulas (enterocutaneous) |

|---|---|

| Enteroenteric | Spontaneous |

| Ileoileal | Postoperative |

| Ileocaecal/colic | |

| Ileosigmoid | |

| Enteroduodenal | |

| Enterogastric | |

| Coloduodenal | |

| Cologastric | |

| Enterourinary | |

| Enterovesical | |

| Enteroureteral | |

| Enterourethral | |

| Colovesical | |

| Enterogenital | |

| Rectovaginal | |

| Anovaginal | |

| Sinus tract | |

| Postoperative |

Given the great clinical heterogeneity associated with fistulising disease, including complications such as abscesses, we need to have a high degree of suspicion to be able to diagnose it. Because of the complexity of these lesions, detailed characterisation using cross-sectional imaging tests is necessary.

Radiological evaluation of penetrating diseaseDefinition and detection of penetrating lesionsTo optimise both the diagnostic and therapeutic management of penetrating lesions in CD, it is important to use consistent and standardised terminology. This aids communication between specialities, given that radiology is an essential tool for the clinical assessment of these patients and for surgical planning, where necessary. There are various consensus documents and expert opinions in the literature which have attempted to standardise the nomenclature used in this context. Table 2 shows the radiological definitions of the different lesions to be found in CD with a fistulising pattern.

Standardised definitions of lesions associated with fistulising Crohn's disease.

| Lesion | Definition | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fistula | Tubular structure originating from the intestinal wall with liquid and/or gas inside showing peripheral uptake of intravenous contrast | They are divided into simple (single extraenteric pathway which connects with another bowel segment) or complex (multiple extraenteric pathways affecting multiple structures) |

| Sinus tract | Blind-ended defects of the intestinal wall arising from the surface of the serosa and extending into the perienteric mesentery without connecting to any other structure | |

| Inflammatory mass (phlegmon) | Mesenteric inflammatory lesion adjacent to inflamed bowel loops, the edges of which tend to be poorly defined, and which shows increased signal (MRI), attenuation (CT) or hypoechoic appearance (ultrasound) respectively, with no fluid content inside | These lesions are not considered drainable percutaneously |

| Abscess | Shows signal or fluid attenuation characteristics. They show capsular enhancement after intravenous contrast injection or an increase in the Doppler recording on ultrasound | May have gas inside |

In this clinical scenario, cross-sectional imaging techniques play a fundamental role in detecting and determining the extent of penetrating lesions, which may follow complex trajectories and affect different segments of the gastrointestinal tract, as well as other organs or the skin.61–63 They are therefore essential for the medical-surgical approach to these lesions, as set out in the treatment algorithm proposed in Fig. 1. In the literature, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and intestinal ultrasound show good sensitivity for the detection of fistulas and collections.63 Although the diagnostic accuracy of these techniques may vary depending on the complexity and extent of the lesions, in general CT or MRI are preferable to ultrasound for detecting intra-abdominal or pelvic fistulas, given their greater ability to provide information relating to the pelvis or deep abdominal planes.64,65

When diagnosing an internal fistula, it is important to provide a detailed description of the type of fistula; it should be defined by the point of origin and the affected organ (for example, enteroenteric, enterourinary or enterogenital; see Table 1). In the case of inflammatory masses or collections, it is also important that the radiologist indicate their location and size in the report. With collections, the proportion of the estimated volume occupied by fluid should also be described, as well as the presence of septa and the feasibility of placing a drain guided by cross-sectional imaging techniques66,67 (Fig. 2). Also important is to specify the detection of a fistula associated with the collection and, if so, the type of fistula, as this could affect the medical-surgical approach and the likelihood of resolution of the same.68 Endoluminal contrast injection into the collection could also help identify fistulous tracts not visible radiologically because they are masked by surrounding inflammatory changes.69

MR enterography of a patient with Crohn's disease with an abdominal collection associated with an ileal stricture. A) Fat-suppressed T1-weighted image in the coronal plane after intravenous contrast injection. A well-defined collection with hyper-enhancement of its wall measuring 24 mm (arrowheads) can be identified, associated with a stricture with inflammatory signs (arrow). B,C) T2-weighted image in axial plane without (B) and with (C) suppression of the fat signal, where the collection can be identified (arrowheads), the content of which shows liquid characteristics, although with less signal than the oral contrast in the intestine. D) Diffusion-weighted image in the axial plane showing the collection with high signal intensity (arrowheads) due to the marked diffusion restriction characteristic of collections.

In cases where the penetrating pattern manifests in the form of perforation,70 CT would be the fastest and most sensitive radiological technique to detect pneumoperitoneum and should therefore be the test of choice when perforation is suspected.71 Intestinal ultrasound or MRI in expert hands could also identify the presence of free gas, but they are not considered the techniques of choice in this scenario.

RecommendationWhen assessing fistulising lesions, we recommend including a detailed radiological evaluation using consistent terminology, which will allow for a better multidisciplinary assessment. CT and MRI are the examinations of choice in this context due to their greater ability to provide a detailed anatomical map, although intestinal ultrasound could be used in some cases or in selected centres. If an examination is proposed that would enable both the characterisation of the type of fistula and drainage of collections/abscesses, we recommend prioritising the use of CT and ultrasound.

Initial approach and multidisciplinary management perspectiveFistulising complications are potentially serious complications which can significantly affect the patient's quality of life. Management should be guided by several key points, including the location, the bowel segments or organs affected, whether or not there is an infectious complication (for example, an intra-abdominal abscess) or an associated stricture, and the luminal inflammatory activity of the CD. CD is already a highly complex disease, and the presence of penetrating intra-abdominal disease (as well as perianal involvement) contributes to the difficulty of day-to-day management. For all these reasons, penetrating complications mean the disease requires a highly detailed approach from an interdisciplinary perspective. This begins with an accurate diagnosis and full radiological assessment (see section "Radiological evaluation of penetrating disease".) Subsequent treatment requires the coordinated involvement of gastroenterologists, surgeons and interventional radiologists. Depending on the anatomical areas affected, it may also require the involvement of other medical specialities, such as endocrinology/nutrition, or surgical specialities, such as urology or gynaecology.

As part of the initial management, when confirming the presence of luminal activity, one of the fundamental objectives has to be the remission of the inflammatory activity, as the fistulising lesions are ultimately a result of the inflammatory process itself in the intestinal wall (Fig. 1). Within the available therapeutic arsenal, corticosteroids remain a fundamental tool in the acute control of the disease. However, in the context of a patient with fistulising disease, steroids should be used with caution, as they are an important risk factor for the development of infections. This means, for example, that patients on treatment with systemic corticosteroids develop larger abscesses than those who are not on steroid therapy.72 Their use should therefore be limited and only in selected cases, provided there are no septic complications.

RecommendationIn simple (uncomplicated) fistulising disease, with associated luminal activity and no indication for surgery in the short term, we recommend the use of systemic corticosteroids to control inflammatory activity. In all other situations, the use of corticosteroids should be limited, prioritising the control of abdominal sepsis and the early initiation of advanced therapies with biologic drugs.

- a

Nutrition

Adequate nutritional support is essential, among other reasons, to prevent post-surgical complications associated with malnutrition.73 Patients with active CD with a fistulising complication, whether or not associated with a septic process, are very likely to meet clinical criteria for malnutrition, so they should always be assessed from a nutritional perspective. The new Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria for malnutrition establish inflammation as a very important aetiology to consider in malnutrition, so it takes on even greater significance in this type of process.74 For an initial assessment, different screening tools can be used, such as the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST),75 the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST)76 or the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF),77 but there is no tool specifically validated in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Patients with a positive screening test or who are to undergo surgery should be referred to a clinical nutrition specialist. Complete intestinal rest was classically recommended to reduce the flow of enteral contents to the fistula, but some studies, although small in size, have indicated that the use of enteral nutrition, preferably for absorption in proximal segments, could reduce the risk of both surgery and postoperative complications.78–80

The latest recommendations of the European Society of Nutrition (ESPEN) recommend the use of total or partial parenteral nutrition in patients with proximal fistulas or high output, although they recommend trying to maintain the oral route simultaneously.81 Regarding the type of formula to be used parenterally, there is no evidence to recommend a specific type, so the use of standard formulas is suggested.

In all patients with active CD and fistulising complications, whether or not associated with a septic process, we recommend a nutritional assessment. This is especially important for patients with a positive nutritional screening test or who are about to undergo surgery. The generally recommended route of nutrition is enteral, although total or partial parenteral nutrition should be considered in patients with proximal or high-output fistulas.

- b

Anticoagulation

Inflammatory bowel disease, especially in active phases or in relation to hospital admission, is a major pro-thrombotic risk factor.82 Therefore, patients admitted due to fistulising complications should receive prophylactic anticoagulation to prevent thrombotic complications, as in all other situations requiring hospitalisation. There is no evidence to suggest that anticoagulation in such situations increases the risk of bleeding.83 However, the likelihood of requiring invasive procedures must be taken into account so that anticoagulation can be discontinued in sufficient time to reduce possible bleeding complications. Low molecular weight heparin at prophylactic doses is considered the option of choice in this context.84 In the case of invasive or surgical procedures, prophylactic heparin therapy should be discontinued 12 h beforehand, or 24 h before if the dose is for anticoagulant purposes.

All patients admitted due to fistulising complications should receive prophylactic anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin.

- c

Multidisciplinary decision

For all the many reasons discussed above, fistulising CD represents a challenge in terms of both diagnosis and treatment. Smooth communication between different specialists is essential to achieve the best results for each patient, and at the very least should involve gastroenterologists, surgeons, radiologists and nursing staff.

Many of these patients are treated in an outpatient setting, and progressive sepsis management and patient optimisation may be necessary. In this situation, MRI of the intestines would be the radiological technique of choice, due to its greater sensitivity in detecting fistulas. When they need to be admitted to hospital, if these patients do not have an initial indication for surgery, they will most likely be treated on a gastroenterology ward. It is therefore advisable at the time of admission to consult and review the patient's condition with the general surgery team, as this will enable a consensus-based approach from the outset. Appropriate imaging tests are also necessary. If an intra-abdominal complication is suspected, all patients should be evaluated with a cross-sectional radiological study, which in the acute setting is usually a CT scan of abdomen and pelvis. Depending on the radiologist's experience and availability, an intestinal ultrasound may be performed, which could provide useful information such as anatomical relationships and, in the case of a collection, the potential for percutaneous drainage. MRI could be a good alternative given its greater ability to define these types of lesion, but it is often not available in the acute phase.

Once the initial assessment is completed, we should be able to determine whether we are dealing with simple or complex fistulising disease, defined by the presence of multiple tracts or associated with a phlegmon or abscess. The evidence and recommendations for each of these scenarios are discussed below. A multidisciplinary approach is essential in all of them, as the risk of septic complications and the need for percutaneous drainage or surgical intervention is high. Close communication and coordinated teamwork are therefore essential to improve the prognosis for these patients.

All patients with fistulising lesions should be prioritised and assessed within a multidisciplinary unit. This provides a comprehensive but also detailed view of the patient, allowing for personalisation and integration of both the medical and surgical perspectives.

"Simple" fistulising diseaseMedical treatment with immunomodulators- a

Thiopurines

There has been little study of the role of thiopurines (azathioprine and mercaptopurine), or that of other immunosuppressants, in the treatment of non-perianal fistulising CD in clinical trials.85–88 No prospective studies with these drugs have specifically evaluated patients with these types of complication. We only have data from studies that include patients with both types of fistulas (perianal and luminal) or from series with a limited number of cases. Despite limited evidence in monotherapy, it has been found that their combined use with biologics, regardless of the type, seems to provide a benefit by reducing the likelihood of surgery in fistulising CD, probably by increasing the levels of the biologic drug, especially with infliximab, or by generating a beneficial synergistic effect when there is a more severe intestinal inflammatory process.89

Thiopurines have proven useful in enteroenteric, enterocolic, gastroenteric and gastrocolic fistulas, although the response rates (partial or complete) reported are very variable, from 0 to 100%, in studies with a very small sample size (generally, fewer than 10 patients).87 In a systematic review of seven studies including a total of 14 fistulas in patients treated with thiopurines, 65% showed a response (43% partial and 22% complete).87,88 In 99 enterovesical fistulas, thiopurines, combined or not with antibiotics, produced a response in 39% of cases overall (15% partial and 24% complete).87,88 For rectovaginal fistulas, thiopurines have shown some utility, with an overall response rate of 50% (42% partial, 8% complete) based on limited experience in 12 cases.90,91

- b

Calcineurin inhibitors

Ciclosporin has been evaluated primarily in the management of rectovaginal fistulas. In this context, it has proven to be very effective during the induction phase, with 89% improvement (45% partial, 45% complete).92,93 Unfortunately, relapse rates are high (38% of all responding patients), even with the simultaneous use of other immunomodulators, which could be partly explained by the low levels of ciclosporin during the maintenance phase.92

There is also information from clinical trials94 and from its use in clinical practice95,96 showing favourable data with the use of tacrolimus in fistulising perianal disease. Similar to ciclosporin, tacrolimus has also shown promising results in rectovaginal fistulas, with an overall response rate of 75% (25% partial and 50% complete), although in very limited series of patients.97,98 However, the information available on its use in internal fistulas is anecdotal, limited to a series of cases with four patients with internal fistulas treated with tacrolimus and aminosalicylates, in which an improvement was observed, in some cases even after having also been refractory to infliximab.99

We do not recommend the use of immunomodulatory drugs as first-choice therapy for fistulising disease. The use of thiopurines as monotherapy is not recommended, while calcineurin inhibitors could be considered in selected cases as bridging therapy or in the absence of other alternatives.

JAK inhibitorsThere are no studies evaluating the efficacy of traditional immunosuppressants for the treatment of enterocutaneous fistulas, but JAK inhibitors are being evaluated for this indication. A sub-analysis of upadacitinib registration studies, including a very limited number of patients with enterocutaneous fistulas, shows that this drug is more effective than placebo, especially in perianal fistulising disease, achieving complete resolution of drainage in almost half of cases after induction and maintaining it in approximately 18% of patients at 52 weeks.100

RecommendationsJAK inhibitors such as upadacitinib have shown promising results in fistulising complications, mainly in perianal fistulising disease, and could therefore be considered in the future as a valid alternative in cases of failure with biological therapy, although the evidence in other types of fistulas is still very limited.

BiologicsBiological therapies, and in particular TNF inhibitors, are the medical treatments with the greatest evidence of efficacy in non-perianal fistulising CD. These lesions, considered a more advanced form of CD, should be treated within a "top-down" or more intensive strategy, given the high risk of complications and disease progression. However, published data confirming the efficacy of biologics also reveal that a combination of different medical treatments is necessary, and even then, surgery cannot always be avoided.

A French retrospective, observational study evaluated the efficacy of TNF inhibitors in 156 patients with internal fistulising disease (43% enteroenteric, 4% enterovesical, 41% with associated abscess, and 29% with multiple tracts). After one, two and five years of follow-up, 83%, 64% and 51% of patients respectively remained surgery-free. These authors also found that the proportion of patients in whom fistula closure was achieved increased progressively over the course of treatment (15%, 32% and 44% respectively).101 However, in a subsequent study conducted in Japan in a cohort of 93 patients with penetrating disease (77% enteroenteric or enterocolonic, 17% enterovesical and 5% enterovaginal) also treated with TNF inhibitors, the five-year fistula closure rate was somewhat lower (27%), with a similar rate for surgery (47%).102 The series to have provided the most evidence in this context to date comes from the ENEIDA registry, where it was possible to analyse 760 patients (51% enteroenteric, 30% enterocolic) who had received different biologic drugs, mostly TNF inhibitors (88%), but there is also data with the use of other treatment targets.89 Of the patients treated with TNF inhibitors, one-third (32%) required surgery. Overall, 31% of patients achieved a reduction in the number of fistula tracts or fistula closure, while 11% of cases developed new tracts or worsening of those already present at the start of treatment. In 24% of patients, the fistulous tracts closed after an average of 15 months of biological therapy, with no differences between the different drugs, with the likelihood of closure decreasing significantly after more than two years of treatment.89

Evidence with targets other than TNF inhibitors remains limited for this indication. Within the BIOSCOPE study, the surgery rate among patients treated with vedolizumab or ustekinumab was 41% and 24% respectively.89 When comparing outcomes across targets, the cumulative probability of remaining surgery-free at one, three and five years of follow-up was 81%, 72% and 67% for TNF inhibitors, 82%, 70% and 70% for ustekinumab, and 73%, 64% and 64% for vedolizumab respectively. Data from another retrospective study comparing the efficacy of vedolizumab and ustekinumab also show that ustekinumab might be a better option in fistulising disease refractory to TNF-inhibitors.103 This same trend has been seen in a subsequent Canadian study which analysed the efficacy of ustekinumab in both fistulising forms (perianal and abdominal), confirming the long-term efficacy of this drug reported in previous series.104

In cases of fistulising disease complicated by abscesses, preliminary data showed that TNF inhibitor therapy could be a suitable option,105 this being subsequently confirmed with data from the prospective MICA study, which evaluated the effectiveness of adalimumab in this context.106 The results show that 74% of patients without prior exposure to biologics can benefit from treatment with adalimumab after 24 weeks, with success being defined as no need for corticosteroids after week 12 and the absence of abscess recurrence, intestinal resection, clinical recurrence or elevated CRP.106 It is worth noting that in this cohort (n = 117), the majority of abscesses affected the terminal ileum (90%), were single (81%), were located in the right iliac fossa or pelvis (45% and 37% respectively) and had a mean size of 29 mm. Despite these characteristics, only 9% of abscesses were drained, primarily due to their small size and difficulty in access. Although abscess size was not associated with decreased treatment efficacy, drainage and disease duration had a negative impact, while inflammatory changes in mesenteric fat were associated with improved outcomes.

Overall, in the remaining studies that have evaluated predictive factors for response in fistulising disease, it appears that patients with less extensive disease, a smaller number of fistulas, and a less marked inflammatory burden show better outcomes. In contrast, patients with more complex lesions, including a greater number of fistulous tracts or additional complications, such as distal abscesses or strictures, are more likely to require surgery.89,101 The BIOSCOPE study also found that the use of immunosuppressants concomitantly with TNF inhibitors could improve outcomes and reduce the risk of surgery, while smoking worsened the prognosis.89

There are other fistulising forms, such as enterocutaneous fistulas, where, although surgery usually plays the predominant role, biologic drugs may also have a part to play. Although data have so far been limited, a GETAID cohort included 48 patients who received TNF inhibitor biologics, mostly infliximab. Fistula closure was achieved in one-third of cases after three months of treatment and in 17% at the end of follow-up. However, despite this benefit, approximately half of patients (54%) required surgical intervention after a median of 16 months.107 In a similar cohort in our setting, lower response rates were reported after treatment with infliximab or adalimumab (13%), with 46% of patients requiring medical/surgical treatment.108 The ECUFIT study, also conducted within the ENEIDA registry, evaluated the management and prognosis of enterocutaneous fistulas, with an overall surgery rate of 69%, the majority of patients achieving fistula closure thanks to surgical intervention.53 However, a subgroup of patients may benefit from medical treatment, primarily TNF inhibitor drugs. Excluding patients undergoing immediate surgery, approximately one-third of patients achieve complete recovery from these types of complicated lesions thanks to biological therapy.

A GETAID study analysed the efficacy of TNF inhibitors in 131 patients with enterogenital fistulas, reporting the results after one year of treatment, where 37% of patients had complete clinical closure of the fistula, 22% a partial response and 41% no response.109 There is even less evidence on the use of biologics in enterourinary fistulas: a small multicentre series that evaluated 33 patients treated with TNF inhibitors found that 45% of patients achieved sustained remission without the need for surgery after approximately three years.110

RecommendationTNF inhibitors are the biological therapy of choice for fistulising complications, while data with other targets are still very limited. We recommend combined biological therapy strategies with thiopurines, especially those based on TNF inhibitors. Otherwise, ustekinumab is a suitable alternative in these cases.

Management of abscesses and septic complications- a

Medical treatment

The presence of an intra-abdominal abscess associated with fistulising CD represents a therapeutic challenge, as it involves the simultaneous combination of a septic condition and an inflammatory process. The inflammatory activity will eventually require the initiation of immunosuppressive or biological therapy, but the presence of an infectious complication will be at least a relative contraindication until it is brought under control.

Factors such as the availability of measures to control the infection, the location and accessibility of the abscess for percutaneous drainage, the patient's general condition, comorbidity and surgical risk, and the patient's prior history of CD will all need to be considered. One of the fundamental factors that will determine the treatment strategy is the size of the abscess. The World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) guidelines on the treatment of abscesses associated with diverticulitis set the cut-off point for interventional management at 4−5 cm.111 Although these data are obtained from a different disorder from inflammatory bowel disease, they are the only guidelines that establish recommendations on management based on the size of the abscess, as there are no such indications in the latest ECCO guidelines.73 Another study from the ENEIDA registry showed that antibiotic treatment can be equivalent to interventional techniques in abscesses of less than 30 mm, while above 50 mm, the rate of complete resolution with surgery is higher than the other options (79% for surgery, 31% for radioguided drainage and 26% for antibiotic therapy).72

In practice, the first step should be adequate control of the infectious focus using broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. There is very little data on this specific situation, so many actions are derived from evidence from intra-abdominal abscesses associated with acute diverticulitis or post-surgical complications. Intra-abdominal abscesses are almost always polymicrobial, with the most frequently isolated microorganisms being Escherichia coli, Streptococcus spp., Enterococci, Candida and anaerobes.112,113 The isolation of enterobacteria is somewhat less common in patients receiving corticosteroids113 and multi-resistant microorganisms can be found in up to 7.6%,112 making it necessary to use antibiotic regimens with broad-spectrum coverage. Although there are no clinical trials specifically designed for this particular scenario, the guideline should primarily cover the Enterobacteriaceae family, Gram-positive cocci and anaerobes.114 The regimen generally associated with greater effectiveness in achieving resolution of abscesses in CD is the combination of ciprofloxacin (400 mg/12 h) and metronidazole (500 mg/8 h), with outcomes being worse using other regimens based on carbapenem (OR: 0.40; 95% CI: 0.20−0.77) or piperacillin-tazobactam (OR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.23−0.96)72. Considering all the evidence, the Surgical Infection Society recommends monotherapy with ertapenem or moxifloxacin, or the use of cefotaxime/ceftriaxone or ciprofloxacin combined with metronidazole in less severely ill patients (grade 1A recommendation). Regimens with piperacillin-tazobactam, imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem and cefepime combined with metronidazole are recommended as empirical therapy for more severe patients (grade 1A recommendation), using aztreonam with metronidazole and vancomycin in case of allergy to beta-lactams.114 In seriously ill patients who do not receive piperacillin-tazobactam or imipenem-cilastatin, enterococcal coverage should be considered and treatment with ampicillin or vancomycin should be added.114

In general, for all of them it is recommended to start treatment intravenously, and the recommended duration in this scenario is at least four weeks.111 Changing to oral at discharge is not associated with a higher rate of surgery compared to intravenous, and this could be achieved by transitioning to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin with metronidazole, moxifloxacin, cephalosporin with metronidazole, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole also with metronidazole.114 However, the intravenous route seems to be associated with lower readmission rates,115 so use of the oral route should be decided on an individual basis and be an option particularly in patients who are less seriously ill.

Patients with intra-abdominal abscesses should receive intravenous antibiotic therapy, with ciprofloxacin combined with metronidazole being the preferred treatment, although alternatives include a combination of cephalosporins and metronidazole or monotherapy with piperacillin-tazobactam or carbapenems. Treatment should last at least four weeks and may be changed to oral before discharge, especially in less seriously ill patients with an adequate response to the intravenous regimen.

- b

Radiological management

In addition to the initial supportive treatment and antibiotic therapy indicated in the previous section, patients with complications of these types should be discussed within a multidisciplinary setting.64 Depending on the characteristics of the abscess, the need for percutaneous drainage may be considered as the primary treatment or as a bridge to surgical intervention, which should be performed on an individual basis, taking into account the characteristics of the patient, the clinical situation and the inflammatory lesions. The possibility of performing image-guided percutaneous drainage is a minimally invasive alternative to surgical drainage which has proven effective in resolving abdominal or pelvic collections that develop both in the context of an outbreak of luminal inflammatory activity and due to postoperative complications,57,64,116–118 although some series have described a higher risk of stoma if it is not accompanied by a subsequent intervention.119 Close coordination between the different teams is necessary, as in patients for whom percutaneous drainage is considered as a bridge to an intervention, this seems to have worse outcomes (in terms of abscess recurrence) when the two procedures are performed within a short period (<2 weeks).120

Image-guided percutaneous drainage of collections can be performed with CT or ultrasound. The decision to use one technique or another depends on the radiologist's experience and the availability of the technique, as well as the location of the collections. In general, ultrasound is reserved for more superficial collections, as it avoids the use of ionising radiation, as well as in paediatric patients,121–123 while CT is used to guide the drainage of deep abdominal or pelvic collections, because it allows better visualisation of both the limits of these collections and the end of the drain.124

In general, imaging-guided placement of a percutaneous drain is considered a moderate-risk procedure.125 Specific assessment of bleeding risk and considerations for the use of blood products or other haemostatic agents should be personalised for each patient. To perform it safely, it is recommended that the INR value be less than 1.5 and that platelet transfusion be considered before the procedure if platelet levels are below 50,000.126

In the procedure report it is important to indicate the lumen of the drain used, the position of the distal end of the drain within the cavity, the volume of aspirated content, whether material has been sent for microbiological analysis,112,113 and post-procedure indications, such as the need to perform saline flushes in case of very thick content. The most common associated complication reported in the literature is local pain, although the main major complication is bleeding due to damage to vessels surrounding the collection or in the path of drain placement.127 With this procedure, the main complications tend to appear during the first few hours after the procedure, so it is advisable to monitor these patients and have healthcare facilities available where they can be monitored and appropriate action taken in case of complications.

When the collection is not accessible to percutaneous drainage, endoluminal intervention (for example, transgastric) may be an option, although these procedures usually require a high level of specialisation and are not therefore widely used.

Ultrasound- or CT-guided percutaneous drainage of abscesses should be indicated for lesions larger than 30 mm in size, while for those larger than 50 mm, surgery offers better results. The choice of this strategy as a sole treatment or as a bridge to an intervention should be made on an individual basis according to the patient and their previous history of the disease. If followed by surgery, this should be performed semi-electively within a period of at least two weeks.

Surgical management of abdominal fistulising Crohn's disease- a

Preoperative studies and patient optimisation

As previously mentioned in the section "Management of abscesses and septic complications", patients with CD should be studied in detail by a multidisciplinary team before surgery is indicated, so that at the time of the intervention the patient is in the best possible general condition from all points of view. Such optimisation will improve the outcomes of the entire process, including patient recovery. As part of this optimisation process, we consider it important to highlight:

- –

Assessment of nutritional status, considering the need for supplementation therapy either enteral or parenteral.128

- –

Optimisation should be multidimensional, and it may be useful to offer contact with patients who have the same disease before surgery.129

- –

If the patient has had prolonged exposure to corticosteroid therapy (>20 mg/day of prednisolone for more than 6 weeks),73 assess the possibility of gradual withdrawal, as such long-term treatment has been associated with an increase in morbidity in terms of the surgery.130

- –

Control of sepsis associated with abdominal collections secondary to penetrating disease, which will give us the chance to take care of the patient's clinical situation and thus defer surgery until the patient is in the best possible condition.73,131 Adequate drainage of abscesses will prevent the need for urgent surgery in a significant number of patients.73

- –

Cross-sectional imaging studies (CT or MRI of intestines) are of vital importance for planning surgery. These studies are aimed at diagnosing the presence of associated stricturing disease, as well as the number and type of fistulas in the different segments of the bowel (proximal and distal), and these should be interpreted by physicians with experience in reading images of patients with CD (see section "Radiological evaluation of penetrating disease".)

- –

The use of an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol in this type of patient could be beneficial, although there is still a lack of studies to confirm its utility.132

- –

- b

Approach to fistulising CD

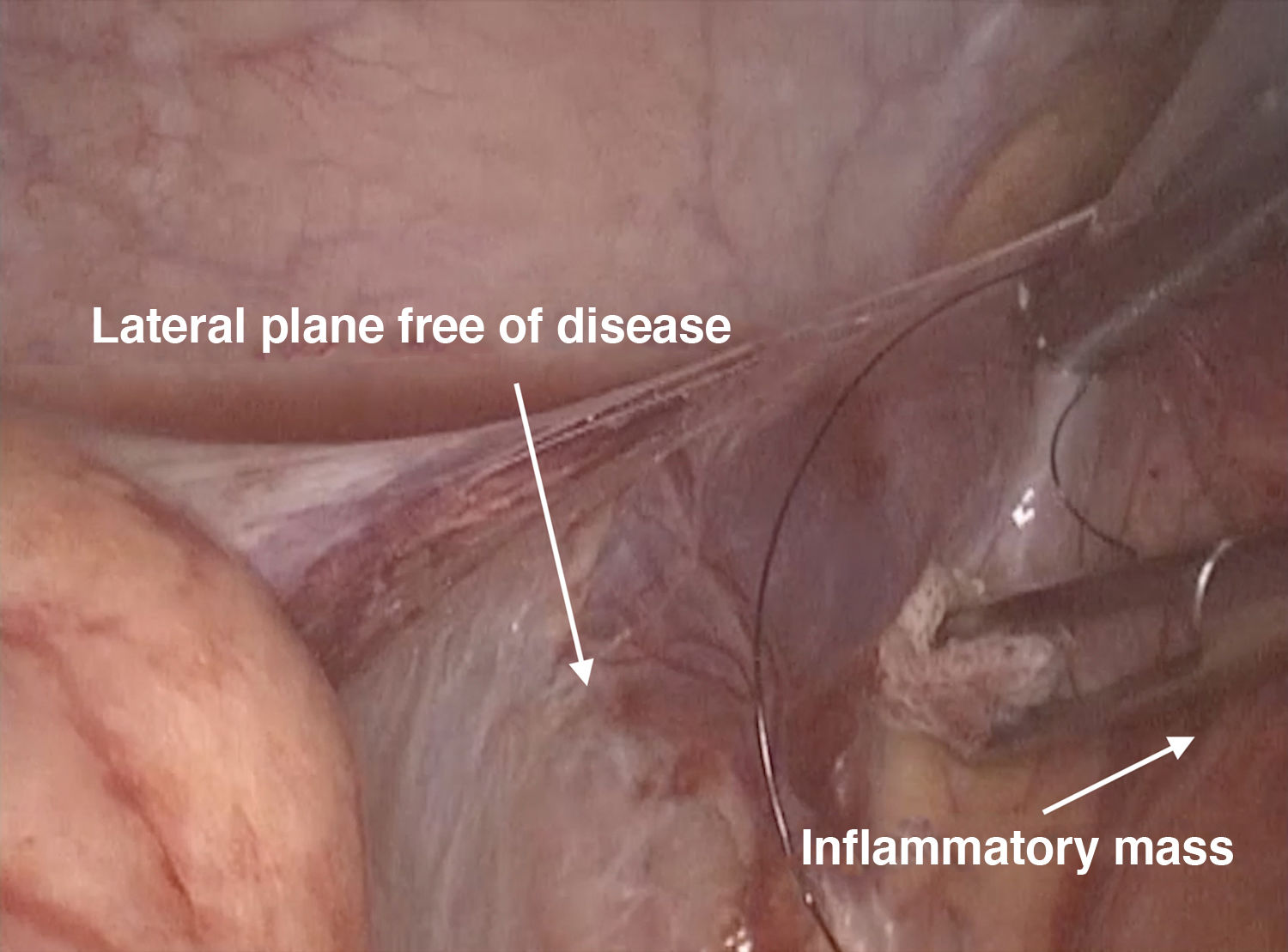

The most common indication for surgery in abdominal CD is complications of the disease itself (strictures and/or fistulas), which may be associated with large inflammatory masses involving segments of the colon and small bowel with associated intermediate collections. All of this creates a distortion of the surgical (embryological) planes typically used to perform this type of intervention. If a laparoscopic approach is chosen, as fistulas from the ileocaecal region to other organs are the most common, trocars will more often need to be placed, simulating the approach of a standard right colectomy, depending on the surgeon's routine practice. It is important to perform a complete examination of the abdomen, which is easier with laparoscopy and can be recorded, describing all identified lesions in detail and acquiring images whenever possible, in order to facilitate the interpretation of the findings for further surgery, complications, postoperative treatment, etc.133 It is also essential to explain each procedure carried out in a structured manner, both clearly and in detail.134

For all the above reasons, the presence of large inflammatory masses, which can include organs as diverse as the proximal small bowel, terminal ileum, right colon and sigmoid colon, may influence the surgeon to not opt for a minimally invasive approach. However, laparoscopic is generally the approach of choice in this type of patient, whatever the scenario.73 This has been widely described in the literature,135,136 and being able to perform the surgery by this route depends mainly on the experience of the surgical team.

A minimally invasive approach is recommended when considering surgical intervention for complex fistulising CD, with laparoscopy being preferable whenever technically possible.

- c

Ileocaecal resection for fistulising CD

The ileocaecal region is the most commonly affected in CD, and it can be associated with fistulous tracts involving other organs.11 With transmural involvement, which means that the intestinal mesentery and, therefore, the mesenteric side, is affected by the disease (unlike ulcerative colitis), it is more likely to find a disease-free dissection plane at the lateral level (anti-mesenteric side) (Fig. 3). The most recommended approach to this type of patient is therefore to mobilise en bloc from lateral to medial, and to perform the en bloc mobilisation with any segment of small bowel that might be adhered to the terminal ileum-caecum; this technique that has been proposed by various different groups.137,138 It is also recommended to pay special attention to the correct identification and release of the duodenum from the dissection plane, as it may be involved within the inflammatory mass. Other groups, particularly those performing intracorporeal anastomosis, carry out this manoeuvre with energy devices. When performing vascular and intestinal mesentery ligation, we have to once again take into account the transmural involvement associated with CD, which leads to inflammation of the wall, and so a higher risk of postoperative bleeding. For this reason, ligation of the intestinal mesentery can be performed extracorporeally, using absorbable sutures to prevent postoperative bleeding. Again, other groups, particularly those performing intracorporeal anastomosis, do said ligation laparoscopically using energy devices (for example, Ligasure™ and Harmonic Scalpel).

The lateral approach for patients with fistulising ileocaecal CD may offer an advantage over the medial approach. Particular attention must be paid to preserving the duodenum and adequate ligation of blood vessels to prevent postoperative bleeding.

- d

Minilaparotomy and ostomy performed

When performing a laparotomy, whether to convert the surgery from minimally invasive to conventional or having started the surgery with an open approach, we suggest always performing laparotomies at the midline in these cases. In patients with CD, the objective of this recommendation is to protect areas of the intestinal wall where a possible ostomy may be necessary. We must remember here the chronic course of CD and the likelihood of repeated surgical interventions in some patients throughout their lives. If an ostomy is needed, it is also recommended that it be placed close to the midline, preferably at the level of the rectus abdominis muscles.

- e

Attitude towards performing an ostomy

Nutritional deficiency and the consequences of fistulising CD have been discussed in detail in the part on "Nutrition" in the section "Initial approach and multidisciplinary management perspective". However, it is important to mention that in many cases these patients are operated on in emergency contexts, without sufficient margin to achieve ideal optimisation, added to which, they may have been on corticosteroid therapy for a prolonged period prior to the intervention. All of this affects the surgeon's decision on whether to perform a primary anastomosis or consider an ostomy. The decision has to be made prior to surgery, based on all the parameters and considering both the medical and surgical aspects reviewed in this document. These aspects include factors such as the presence of anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia or hypoproteinaemia, or the inability to adequately reduce (ideally below 20 mg/day of prednisolone73) or completely reduce the dose of corticosteroids, which should make us consider performing a temporary ostomy.

When surgery is indicated for fistulising CD limited to the ileocaecal region, and if the decision is not to perform a primary anastomosis, we have to take into account that the distal end of the transverse colon will not behave as it normally does in patients operated on for other emergencies which prevent primary anastomosis. This consideration is made more due to the patient's poor general condition than to the disease itself, as the transverse colon is not usually affected. For everything discussed up to this point, we suggest that the distal end not be left in the abdominal cavity, as it could be susceptible to dehiscence of the suture with the obvious consequences, but rather directed towards the exterior with the ileostomy or placed in the subcutaneous cellular tissue (a manoeuvre that would also facilitate a subsequent bowel transit reconstruction) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.Image illustrating the creation of an ileostomy in a patient operated on for fistulising CD in which the distal end of the colon opens into the subcutaneous cellular tissue (SCT), preventing complications if it opens during the postoperative period, and in turn facilitating the subsequent bowel transit reconstruction surgery in a second stage.

In the case of a laparotomy, it should be performed close to the midline and taking into account the likelihood of repeat interventions. In patients with an ileocolic resection and in whom a primary anastomosis is not performed, it is recommended that the distal colonic end be directed to an ostomy or subcutaneous tissue.

- f

Treatment of ileosigmoid fistulas

Relatively frequently, patients with advanced CD will develop fistulous tracts between the distal ileum and the sigmoid colon. The treatment of this situation has some particular aspects to take into account. First, it should be clarified that these fistulas are usually secondary to ileal disease and not to colon involvement, so treatment of the sigmoid colon can and should be as conservative as possible. Taking this precept into account, in patients without activity in the sigmoid colon, the treatment of choice for the fistula will be determined by the location of the fistulous tract. In patients with a fistulous tract affecting the anti-mesenteric border, it would be advisable to perform debridement and simple raffia associated with ileocaecal resection (considering bowel preparation in these patients). However, in patients with a fistulous tract in the mesenteric border, we recommend performing a sigmoidectomy and primary anastomosis associated with ileocaecal resection.

- g

Treatment of enterocutaneous fistulas

Within fistulising lesions, this type of fistula includes complex lesions affecting the abdominal wall, so, regardless of the cause, the approach to this type of complication always requires a multidisciplinary team, including surgeons, nurses, an interventional radiologist, gastroenterologist, nutritionist and stoma therapists.40,139 The first thing to do in the case of an enterocutaneous fistula is to categorise it according to the daily output of the fistula, which can be low (less than 200 ml), moderate (200−500 ml) or high (more than 500 ml).139 Once the fistula has been categorised, it must be adequately characterised using imaging tests interpreted by an experienced radiologist, as this will make it possible to determine the complexity of the lesion, the presence of local complications (associated phlegmon or abscess) or stricturing, and the bowel segments involved, and whether inflammatory changes can be seen in these segments or their relationship with the surgical anastomosis.

When treating patients with enterocutaneous fistulas, initial management includes fluid resuscitation and medical management of any internal environmental imbalance, while at the same time, reducing the fistula output with medication (proton pump inhibitors, loperamide, somatostatin, octreotide, lanreotide) may be considered.140 Enteral (preferred) and/or parenteral nutrition also plays a fundamental role.

In some cases with high-output proximal enterocutaneous fistulas, the use of "fistuloclysis" may be an alternative to ensure adequate nutrition. This procedure consists of using the fistula orifice to administer enteral feeding directly, and has been reported to be successful in some series.141 Regardless of the procedure, in all cases, daily calorie count and nutritional status must be closely monitored by a specialised team to tailor the supplemental intake to the individual.

Closure of the fistula is achieved in most cases (84%), usually by surgery.53 However, in some cases conservative management may be sufficient and achieve spontaneous closure of the fistula.142 Closure is more likely to be achieved in spontaneous and/or low output fistulas, but the availability of biological therapies has changed the management of these complications over the last twenty years or so, as we have discussed in previous sections.53 Some of these patients, particularly those without an active septic focus, are candidates for the use of biologic drugs, mainly TNF inhibitors,53,107,108 especially in patients with active inflammatory activity secondary to the disease.107,108 The likelihood of closure of these fistulas has increased significantly in recent years, but the use or combination of a surgical approach with a biological therapy should be decided as part of a personalised assessment and in multidisciplinary teams.53,107

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also been tested, injected locally at the fistula site, promoting its closure.143 Lastly, most patients will require surgery as a definitive treatment for this type of fistula. Prior to this, the patient's condition should be optimised, sepsis controlled and adequate nutritional status ensured. Due to the complexity of these cases, these surgical interventions should be performed in centres with experience in managing this type of lesion.

The treatment of ileosigmoid and enterocutaneous fistulas is a challenge for both clinicians and surgeons. In all cases, a multidisciplinary approach, preferably in experienced centres, should include special emphasis on proper staging of the disease and preoperative patient optimisation, which may be associated with better overall outcomes.

ConclusionsFistulising CD is a common complication throughout the natural history of the disease. Although the diagnosis and management of the disease have improved considerably in the last twenty or thirty years, detection of fistulas remains a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. This is because of the different types and complexity of fistulas, but also the fact that the previous disease history and the assessment at the time the fistulising complication develops also have to be taken into account when deciding on medical treatment, percutaneous drainage or surgery. The management of fistulising complications therefore requires close collaboration between different specialities, as in most cases, successful treatment will require a combination of measures aimed at controlling both sepsis and inflammatory activity, as well as the patient's nutritional status, with the aim of improving the long-term prognosis of the disease.

FundingIRL receives funding through a grant from the Basque Government-Eusko Jaurlaritza (Nos 2020111061 and 2023222006).

IRL has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from AbbVie, Adacyte, Alfasigma, Biogen, Chiesi, Faes Farma, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly, Mirum Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda and Tillotts Pharma; research funding from AbbVie.

DCD has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from AbbVie, Chiesi, Ferring, Faes Farma, Janssen, Takeda and Tillotts Pharma.

JR has received funding to participate in training activities or as a consultant from Takeda, Ferring, Agomab, Boehringer Ingelheim, Alimentiv, Lument and Gilead; and research funding from AbbVie.

MC has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from AbbVie, Adacyte, Chiesi, Ferring, Janssen, Takeda, Tillotts Pharma, Pfizer, Kern, Gilead and Dr. Falk.

RFI has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from AbbVie, Adacyte, Chiesi, Casenrecordati, Falk, Ferring, Faes Farma, Janssen, Kern, MSD, Pfizer, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Takeda and Tillotts Pharma.

MI has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from AbbVie, Chiesi, Janssen, Kern, MSD, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Takeda.

MBA has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from Pfizer, MSD, Takeda, AbbVie, Kern, Janssen, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, Alfasigma, Eli Lilly, Tillotts Pharma, Faes Farma, Chiesi and Adacyte.

AGC has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from Pfizer, MSD, Takeda, AbbVie, Kern, Janssen, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, Alfasigma, Eli Lilly, Tillotts Pharma, Faes Farma, Chiesi and Adacyte.

LM has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant, or has received research funding from MSD, AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Biogen, Galapagos, Kern Pharma, Eli Lilly, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Tillotts, Dr. Falk Pharma, Ferring, Medtronic and General Electric.

IO has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from AbbVie, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Kern Pharma and Faes Farma; and has received research funding from AbbVie and Faes Farma.

FRM has received funding to attend or participate in training activities or as a consultant from AbbVie, Johnson & Johnson, Kern Pharma, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Takeda, Ferring, Faes Farma, Tillotts Pharma and Dr. Falk Pharma.

YZ has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support, and consulting fees from AbbVie, Adacyte, Alfasigma, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dr. Falk Pharma, Faes Pharma, Fresenius Kabi, Ferring, Galapagos, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Kern, Lilly, MSD, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi, Shire, Takeda and Tillotts Pharma.

GP and NA have no conflicts of interest to declare for this work.