In our opinion there is an imbalance between the relevance of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and the resources that are provided.

ObjectiveTo review the different factors that determine (or should determine) the interest of gastroenterologists in IBS, comparing it with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For this, 7 different areas have been analyzed: 1. Medical impact; 2. Social impact; 3. Academic importance; 4. Clinical relevance; 5. Scientific relevance; 6. Public relevance; and 7. Personal aspects of the doctor.

ResultsThe prevalence is 10 times higher in IBS, which represents up to 25% of gastroenterologist visits. Both pathologies alter the quality of life, in many cases in a similar way. The social cost is very important in both cases (e.g.: absenteeism of 21 and 18%) as well as the economic cost, although much higher in medication for IBD. Academic dedication is more than double for IBD, both in university and in MIR training. Scientific relevance is greater in IBD, with a number of publications four times higher. Public relevance is not very different between the two entities, although IBD patients are more associative. Doctors prefer IBD and tend to stigmatize IBS.

ConclusionIn our opinion, to reduce this imbalance between needs and resources, human and material, in IBS it is essential to make drastic changes both in educational aspects, communication skills, prioritization according to the demands of patients, and reward (personal and social) of physicians.

En nuestra opinión existe un desequilibrio entre la relevancia del síndrome del intestino irritable (SII), y los medios que se le proporcionan.

ObjetivoRevisar los diferentes factores que determinan (o deberían determinar) el interés de los gastroenterólogos por el SII, comparándolo con la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII). Para ello se han analizado 7 áreas diferentes: 1. Impacto médico; 2. Impacto social; 3. Importancia académica; 4. Relevancia clínica; 5. Relevancia científica; 6. Relevancia pública; y 7. Aspectos personales del médico.

ResultadosLa prevalencia es 10 veces superior en el SII, suponiendo hasta el 25% de las visitas del gastroenterólogo. Ambas patologías alteran la calidad de vida, en muchos casos de forma semejante. El coste social es muy importante en ambos casos (ej.: absentismo del 21 y 18%) así como el económico, aunque muy superior en medicación para la EII. La dedicación académica es más del doble para la EII, tanto en la universidad como en la formación MIR. La relevancia científica es mayor en la EII, con un número de publicaciones cuatro veces superior. La relevancia pública no es muy diferente entre las dos entidades, aunque los pacientes con EII son más asociativos. Los médicos prefieren la EII y tienden a estigmatizar el SII.

ConclusiónEn nuestra opinión, para disminuir este desequilibrio entre necesidades y recursos, humanos y materiales, en el SII es imprescindible realizar cambios drásticos tanto en los aspectos educativos, de habilidades de comunicación, de priorización de acuerdo con las demandas de los pacientes, y de recompensa (personal y social) de los médicos.

To say that a doctor's job is to help patients is stating the obvious. But not all doctors are capable of caring for all patients adequately. Human diseases are so numerous and so complex that it is impossible for a single person, however intelligent or dedicated they may be, to have all the necessary knowledge. This is the reason why medical specialties were developed. They include the digestive system, which straddles both gastroenterology and hepatology, Thus, most specialists in this field take a greater interest in one category or the other: "the tract" or "the liver". Furthermore, those who engage solely or primarily in gastroenterology have their preferences, sometimes with monographic consultations on certain diseases: inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the pancreas, cancer of the digestive system, coeliac disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID), etc.

What is not very clear, at least in our understanding, is who decides to work in one area or another of gastroenterology, and how and why they do so1. Because of the number of patients? Their needs? The research prospects? Because it is the doctor's personal "hobby" or the environment in which they train? The truth is that there are areas of gastroenterology that are "very attractive" to young gastroenterologists, and others that are not so appealing (or even "disliked"). Endoscopy is the favourite of the vast majority of these young specialists. This is logical, given that it combines all the characteristics of modern society: technology, imaging and immediacy. On the other hand, the FGID, particularly irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), are at the bottom of the list. Few gastroenterologists choose this area of super-specialisation, perhaps because it requires empathy, time and patience (qualities currently in short supply).

In turn, the interest and investment of the pharmaceutical industry in certain diseases can also influence physicians' chosen areas of expertise. In this regard, there are definitely 'rich conditions' and 'poor conditions'. IBD is one of the former, and IBS one of the latter2.

The purpose of this paper was to review the different factors that determine (or should determine) the interest of gastroenterologists in IBS as compared to IBD.

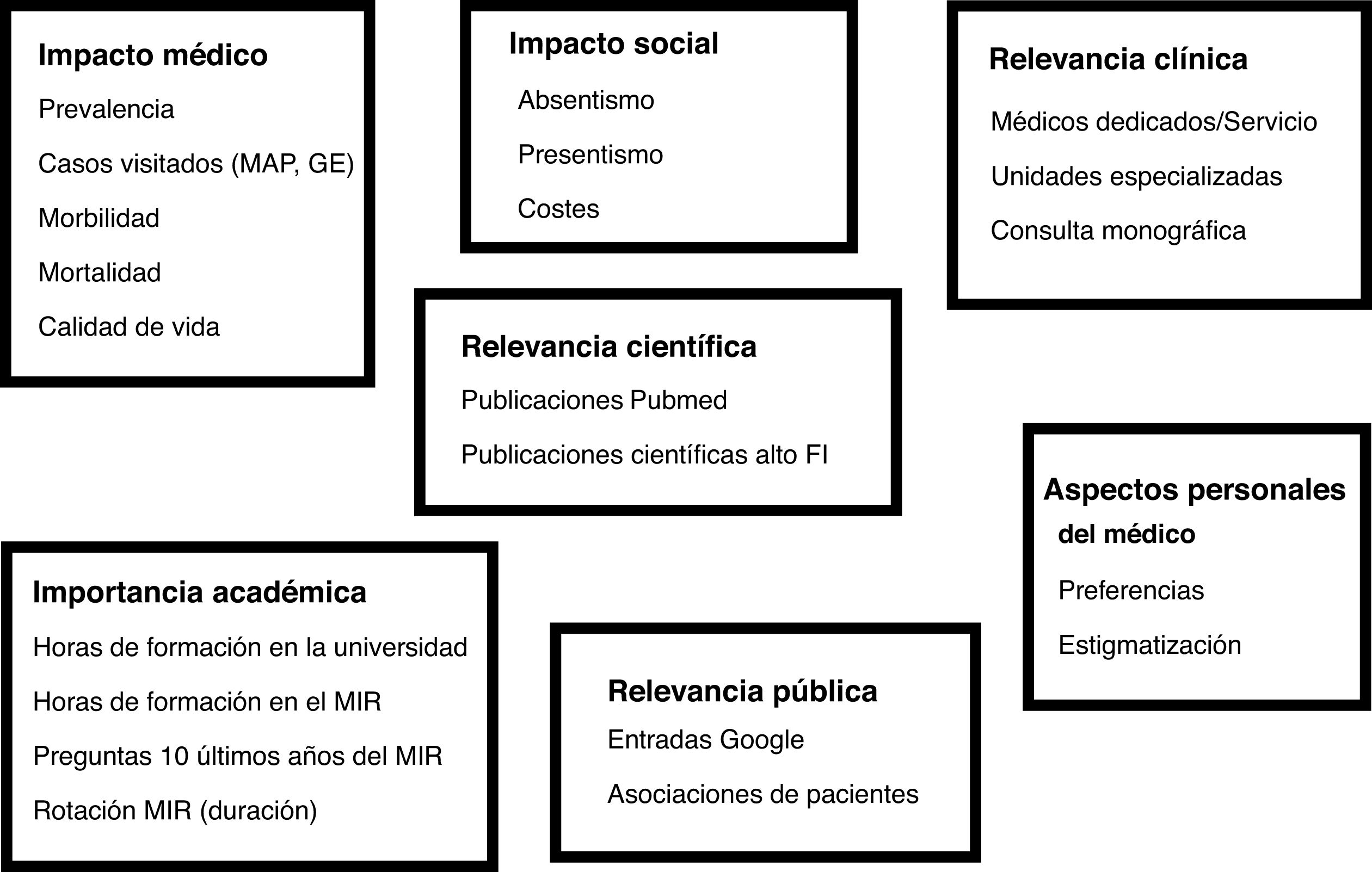

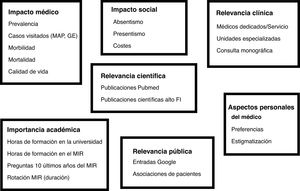

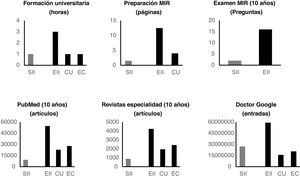

MethodsUsing the available data, several aspects of IBS were assessed as objectively as possible and compared to those of IBD: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD). To this end, their relevance and needs were systematically analysed. Seven different areas were evaluated (Fig. 1): 1. Medical impact (prevalence, cases seen, morbidity, mortality, quality of life) ; 2. Social impact (absenteeism, presenteeism, costs); 3. Academic importance (hours of university training, hours of preparation for the medical internship access examination [MIR], number of questions in the MIR examination, length of rotation during the internship); 4. Clinical relevance (dedicated physicians/service, specialised units, monographic consultations); 5. Scientific relevance (publications in PubMed; publications in specific gastroenterology journals); 6. Public relevance (Google entries; patient associations), and 7. Personal aspects of the physician (preferences, stigmatisation).

The following aspects of IBS, IBD (collectively, UC + CD), UC, and CD were analysed by a review of the scientific literature (PubMed, MEDLINE), whenever data were available: prevalence, cases seen in primary care and gastroenterology, morbidity, mortality and impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). General information was obtained, indicating the data source and whenever possible the corresponding data for Spain.

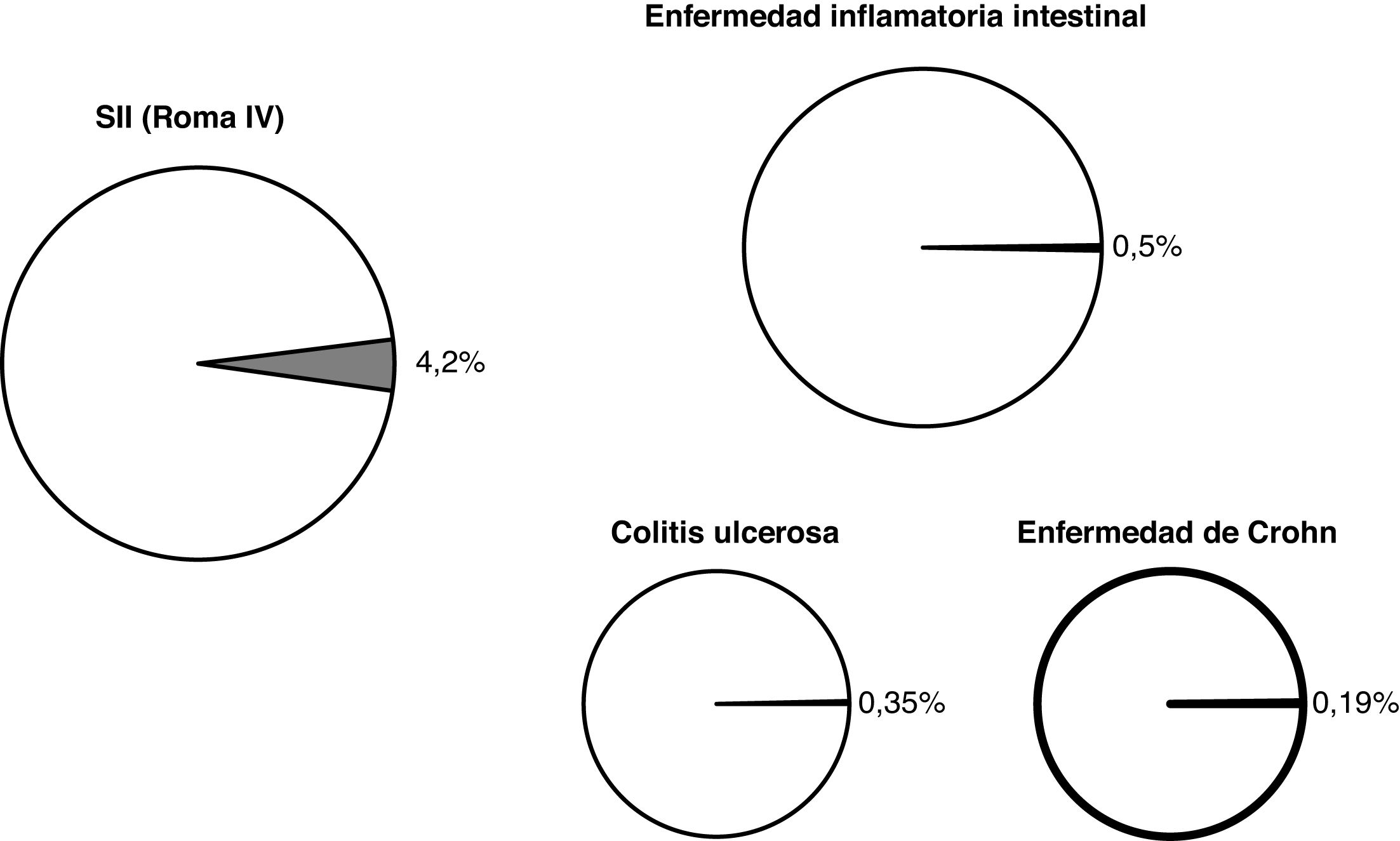

Social impactWhenever data were available, the following aspects were analysed: work/school absenteeism due to illness, presenteeism (attending the workplace/place of study, but not being fully functional due to illness) and direct and indirect costs in each case.

Academic importanceThe hours of theoretical teaching during medical degree training were counted for both IBS and IBD (overall: UC + CD), in UC and in CD in 10 Spanish universities (Universidad del país Vasco-EHU [University of the Basque Country], Universidad de la Laguna [University of La Laguna] (Canary Islands), Universidad de Zaragoza [University of Zaragoza], Universidad de Barcelona [University of Barcelona], Universidad Autónoma de Madrid [Autonomous University of Madrid], Universidad Complutense de Madrid [Madrid Complutense University], Universidad de Navarra [University of Navarre], Universidad de Santiago de Compostela [University of Santiago de Compostela], Universidad de Valencia [University of Valencia], Universidad de Córdoba [University of Cordoba]). The data were obtained from the teaching programmes through lecturers in Digestive System of the corresponding schools of medicine. The hours devoted to these topics in preparation for the MIR in four of the most prestigious centres (Asturias, CTO, AMIR and PROMIR) were also collected. In addition, the MIR examinations from the last 10 years were reviewed by selecting the number of questions related to each topic. Finally, the supervisors of interns from 10 hospitals with Gastroenterology MIR were contacted (Hospital de Donostia [Donostia Hospital], Hospital de la Laguna [La Laguna Hospital] (Canary Islands), Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa de Zaragoza [Lozano Blesa Clinical Hospital, Zaragoza], Hospital Clínic de Barcelona [Barcelona Clinical Hospital], Hospital de la Princesa de Madrid [de la Princesa Hospital, Madrid], Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid [San Carlos Clinical Hospital, Madrid], Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra [Navarre Hospital Complex], Complejo Hospitalario de Santiago de Compostela (CHUS) [Santiago de Compostela Hospital Complex], Hospital La Fe de Valencia [La Fe Hospital, Valencia], Hospital Reina Sofía de Córdoba [Reina Sofía Hospital, Cordoba]), all of them university hospitals, to ascertain the time spent during their training on the FGID (here, it was impossible to separate IBS from general training in the FGID) and IBD.

Clinical relevanceIn 10 hospitals with more than 15 senior gastroenterologists, the number of them with a heavier focus on IBS (along with other FGID) or IBD was determined, as well as the number of hospitals with a specific unit for FGID and/or IBD. In addition, the number of centres in Spain with monographic consultations and specialised units for these pathologies was investigated through the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] (GETECCU) and the Asociación Española de Neurogastroenterología y Motilidad [Spanish Association of Neurogastroenterology and Motility] (ASENEM).

Scientific relevanceThe number of publications cited in PubMed over the past 10 years of any origin or Spanish origin under the headings of IBS, IBD, UC or CD was reviewed. Publications in relevant speciality journals were also quantified.

Public relevanceThe number of entries in Google under the headings of IBS (irritable colon), IBD, UC or CD was quantified. In addition, a search on the number and location of patient associations for IBS and IBD was performed on the Internet.

Personal aspects of the physicianThe studies related to physicians' preferences and possible stigmatisations of IBS and IBD were analysed through the review of the scientific medical literature (PubMed, MEDLINE).

Stigmatisation is defined as someone feeling different or inferior due to the way they are treated on account of a personal condition. It occurs mainly in mental illnesses, but also in others such as infectious diseases (classic examples: leprosy, AIDS), cancer, obesity, epilepsy, etc.

Stigma is conceptualised in three domains: perceived, internalised and public3. Perceived stigma refers to how the individual feels about the negative attitudes of others towards their condition; when the person accepts the negative behaviours about their disease and incorporates them into their identity, this is referred to as internalised stigma; and public stigma indicates actual or evident negative or discriminatory acts3.

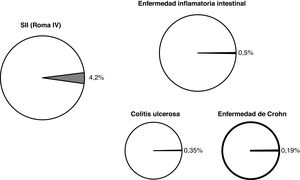

ResultsMedical impactThe prevalence of IBS varies according to the diagnostic criteria used, ranging from 12.1% if the Rome I criteria are applied to 3.3% if the Rome II criteria are applied4. In a recent epidemiological study that collected this datum in 26 countries applying the Rome IV criteria, the overall and Spanish prevalence of IBS were 4.1% and 4.2%, respectively5 (Fig. 2).

The prevalence of IBD is much lower, although its progressively increasing trend continues to be confirmed. A systematic review of population-based studies confirmed that the highest prevalence figures are to be found in Europe and the United States, with UC values of 0.50% in Norway and 0.29% in the United States and CD values of 0.26% in Norway and 0.32% in Canada6. In Spain, some studies have already surpassed the global prevalence of IBD of 0.5% (0.35% for UC and 0.19% for CD)7.

IBS accounts for a significant number of gastroenterologist consultations. In a study conducted in Spain, it represented 50% of the consultations by more than half of the gastroenterologists8. Although we do not have primary care consultation data for Spain, in the United States the percentage is 3%9.

We found no data on the number of visits for IBD, although given its lower prevalence it may be assumed to represent a much smaller number of gastroenterologist consultations and be practically non-existent in primary care consultations.

Patients with IBS suffer from higher morbidity than the general population and, for example, have a higher prevalence of diseases such as gastroesophageal reflux, peptic ulcer, dyspepsia, depression or asthma; or surgeries such as appendectomy, cholecystectomy or hysterectomy10,11.

In the case of patients with IBD, in addition to possibly presenting a large number of extraintestinal manifestations, a higher prevalence of immune-based diseases, such as psoriasis or ankylosing spondylitis, and of non-immunologically-mediated diseases, such as anxiety, depression, cholelithiasis or renal lithiasis has also been demonstrated12.

Patients with IBS are known to have poorer HRQoL compared with the general population, as was found in Spain using questionnaires such as the SF-3613 or the PROMIS-10 Quality of Life Scores (Physical And Mental)5. Poorer quality of life has also been described in IBD patients. Logically, HRQoL is worse in the active phases of the disease than in the quiescent phases, and an improvement is observed after medical treatment or surgery14. Perhaps the most important fact is that when patients seen at the same referral centre are compared, and under the same circumstances, HRQoL is equally decreased in cases of IBD and IBS15.

Unlike IBS, IBD has been consistently associated with a certain increase in overall mortality. Thus, in a recent study conducted in Spain, the adjusted mortality rate was 1.28 (95% CI: 1.6−1.4) for UC and 1.85 (95% CI: 1.62–2.12) for CD7.

In patients with IBS, although the disorder itself does not reduce longevity, the latter may be affected by wrongly indicated surgery11 or because of an increase in the number of suicides16.

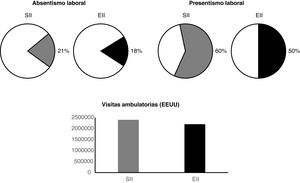

Social impactThe social impact of IBS and IBD is very significant (Fig. 3). The cost of IBS is high, and in Spain 60% of patients have seen the doctor once for their intestinal problems, whereas 16% have seen the doctor more than once a month in the last year 13. Absenteeism figures are also substantial, in that 21% of IBS patients had taken sick leave and up to 8% had been off sick for more than a month in the last year13. It has also been shown that IBS patients cannot perform their work activities normally, and 60% report some kind of decrease in their capacity; this occupational presenteeism is severe in 7.7% of cases13.

A negative impact of IBD on work capacity has also been described, with an absenteeism rate of 18% and a presenteeism rate of 50%17.

In addition to labour costs, IBS entails significant healthcare costs and accounts for more than 2,400,000 outpatient visits per year and more than 440,000 days of hospital stay in the United States18. Although CD and UC are less prevalent diseases, patients who have them also generate very high healthcare costs. A US study found that the number of outpatient visits per year was 2.2 million, with 115,934 emergency department visits and 89,111 hospital admissions19.

In Spain, partial data are available on IBS, with a predominance of moderate-severe constipation, in which healthcare costs reach €1635 a year per patient20.

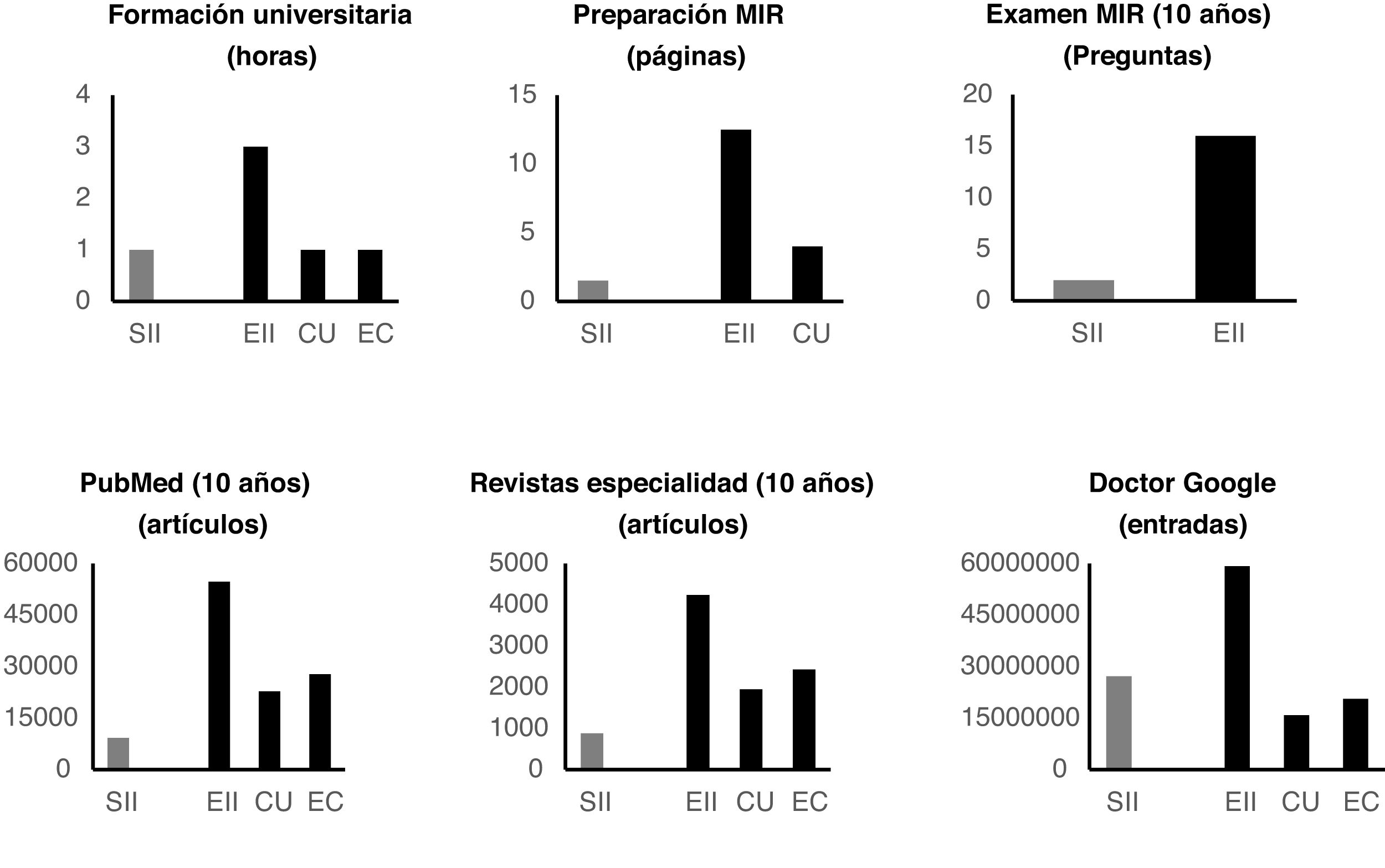

Academic importanceThe hours (median and [range]) spent on university theoretical training at the 10 Spanish universities evaluated were as follows: for IBS, one hour [0-1]; for IBD as a whole, three hours2–4; for UC, one hour [0.5-2]; and for CD, one hour [0.5–2].

Regarding the importance of both topics in the MIR examination, in the last 10 years there have been 16 questions on IBD and only two questions on IBS. In addition, the pages devoted to these topics in preparation for the MIR examination in four of the most prestigious academies (Asturias, CTO, AMIR and PROMIR) range from 3 to 11 pages for the FGID as a whole, with a median of 6.5 pages and between 6 and 26 pages for IBD, with a median of 12.5 pages. More specifically, a mean 1.5 pages is devoted to IBS and a median of 4 pages to ulcerative colitis (Fig. 4).

Clinical relevanceOnce again, on evaluating the 10 hospitals selected for the study, we found that the average number of senior physicians with a greater dedication to FGID (there are no specialists just for IBS) was 2 [0-2], whereas 42–4 had a greater dedication to IBD.

The number of centres with specialised FGID units (there are no dedicated IBS units) was 5, and in IBD 10 (in total).

Scientific relevanceThe PubMed search engine found that in the last 10 years 9200 articles have been published under the term "irritable bowel syndrome" (IBS), 54,700 articles with the term "inflammatory bowel disease" (IBD), 27,800 articles with the term "Crohn's disease" (CD) and 22,800 articles with "ulcerative colitis" (UC).

Repeating the same search in the last 10 years according to the different journals specifically dedicated to gastroenterology yielded the following data. Gastroenterology, IBS: 200; IBD: 931; CD: 462; UC: 364. Gut, IBS: 119; IBD: 634; CD: 353; UC: 263. Am J Gastroenterol, IBS: 267; IBD: 710; CD: 369; UC: 290. Dis Dis Sci, IBS: 147; IBD: 923; CD: 559; UC: 491. Scand J Gastroenterol, IBS: 92; IBD: 579; CD: 374; UC: 337. Gastroenterol Hepatol, IBS: 22; IBD: 232; CD: 164; UC: 123. Rev Esp Enferm Dig, IBS: 32; IBD: 229; CD: 146; UC: 85 (Table 1).

Number of articles published during the last 10 years in speciality journals.

| Journal | IBS | IBD | UC | CD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastroenterology | 200 | 931 | 364 | 462 |

| Gut | 119 | 634 | 263 | 353 |

| Am J Gastroenterol | 267 | 710 | 290 | 369 |

| Dig Dis Sci | 147 | 923 | 491 | 559 |

| Scand J Gastroenterol | 92 | 579 | 337 | 374 |

| Gastroenterol Hepatol | 22 | 232 | 123 | 164 |

| Rev Esp Enferm Dig | 32 | 229 | 85 | 146 |

CD: Crohn's disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; UC: ulcerative colitis.

The total is 879 for IBS, 4238 for IBD, 2427 for CD and 1953 for UC.

Public relevanceThe number of Google entries under the different headings for IBS, IBD, UC or CD is shown below (Table 1): IBS 27,200,000; irritable colon 14,700,000; SII 722,000; colon irritable 18,500,000; IBD 59,200,000; EII 1,480,000; UC 15,900,000; CU 3,640,000; CD 20,600,000 and EC 1,910,000.

Counting the number and location of IBS and IBD patient associations proved to be extremely challenging. On many occasions they are local, whereas on others they are not clearly advertised. It is clear, however, that IBD patient associations are far more common and numerous than their IBS counterparts. In fact, Europe has the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA), which represents 34 national patient associations21. There is no similar entity for IBS in Europe. It is true that there are a number of national associations, such as the Association de Patients Souffrant du Syndrome de l’Intestin Irritable (APSSII) in France, the IBS Network in the UK or the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Association (as part of theIrritable Bowel Syndrome Self Help and Support Group).

Spain has the Asociación Española de Afectados de Síndrome de Intestino Irritable [Spanish Association of People Affected by Irritable Bowel Syndrome] (AESII), and previously the Associació d'Afectats de Colon Irritable de Catalunya (AACICAT), founded by Esther Martí in 200422, which has enjoyed periods of greater and lesser activity but has failed to achieve true relevance due to its low number of affiliates.

In contrast, in IBD, the Spanish Asociación de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa [Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Association] (ACCU) is a confederation that was conceived as an association in 1987 and has more than 8000 members in 36 groups, provincial and/or by autonomous community (region). The ACCU maintains a close relationship with GETECCU.

Personal aspects of the physicianStudies have shown that gastroenterology residents prefer to focus on patients with organic diseases rather than functional ones and consider that care to the latter while they are on-call is less important23,24. In fact, doctors tend to underestimate the number, severity and impact of IBS symptoms compared to diseases with similar symptoms such as IBD or coeliac disease23,25,26. Many admit to being frustrated at it being an "uncertain diagnosis" and because it is "not curable". They also admit their intolerance towards what they term the "typical IBS patient"27. To add insult to injury, symptoms are more often trivialised in women than men28. This unequal treatment of IBS patients is heightened in some ethnic minorities. Thus, in the United States, there are clear differences in the management of the syndrome when Afro-American, Asian, or Hispanic patients are compared to white patients29.

Patients' opinions about this type of healthcare are logical: they feel that they are not treated "seriously", they are not believed, they are demeaned, they are treated as "neurotic" and they are stigmatised30,31. They feel as if the doctor has not been very helpful and has failed to give them sufficient information or proper treatment32,33. The outcome is that about half (54%) rate the visit as "negative", 11% "positive" and 35% "neutral"34.

Several studies have assessed stigmatisation in patients with IBS and IBD35–37. Young people with IBD would reportedly rather not talk about their disease because of the stigma they perceive and feel38.

Both IBS and IBD patients with perceived stigma have more symptoms, greater anxiety and depression and poorer quality of life37. However, those with IBS had more perceived stigmatisation originating from their physicians than those with IBD37. Moreover, when public stigmatisation (reported by other people) in patients with IBS, IBD, and chronic asthma was compared it was significantly higher for the first group. Something similar occurs when stigmatisation in functional somatic syndromes (including IBS) is compared to organic diseases (including IBD)39. In fact, stigma levels in IBS are on a par with AIDS and obesity40,41. The obesity aspect is also interesting.

DiscussionFollowing the analysis of the different aspects that determine the relevance of IBS and IBD, there is no doubt that both pathologies are clinically and socially significant. Prevalence and number of cases seen is high, and the impact on HRQoL is considerable. However, on comparison, it transpired that while prevalence and visits are clearly higher for IBS and the impact on HRQoL is similar, the relevance afforded to it and the care resources available in gastroenterology are much higher in IBD. Thus, the hours of university education allocated to either subject, the intensive preparation for the MIR, the number of questions in the examination or rotation time during internship is clearly lower for IBS than for IBD. This means that the resources dedicated to them are also very different: fewer doctors specialising in FGID, with fewer monographic consultations and specific units.

Discrepancies between what occurs in IBS and doctors' perception create a worrying gap in the doctor-patient relationship. Several studies have shown that a good doctor-patient relationship is one of the best predictors of a good prognosis42–46. In particular, in patients with IBS, an empathetic doctor-patient relationship is known to favour improvement in symptoms and quality of life44. The fact that doctors tend to underestimate IBS23,25,26 or that young doctors would rather treat patients with organic diseases than those with functional diseases22,24 does not help matters. This may be either because they think (somewhat oddly) that caring for IBS patients is not part of their responsibility, or because they are not "comfortable" (which is troubling) due to a lack of training in the management of these cases44,45. Even in the 21st century, there are doctors with a "Doubting Thomas" attitude who do not believe in what they do not see, or what is worse, do not accept what they do not understand: neurotransmitters, microinflammation, hyperalgesia, microbiota, etc.

These differences in the relevance afforded to IBS versus IBD are amplified by additional factors: several studies indicate that more than 50% of primary care physicians view IBS as an exclusion diagnosis and many limit treatment to fibre and spasmolytics47,48. Only 50% of IBS patients receive a definitive diagnosis after they have been seen by a doctor49.

The people who are truly invested in and concerned about what happens to them are the actual IBS patients, and this is demonstrated, even if only indirectly, by the huge number of entries in the most widely used search engine, Google.

Patient associations are clearly more successful for IBD, especially in Spain. Whether this success is due to the type of disease (organic vs. functional), the type of patient (more or less gregarious), the doctors who support them or the pharmaceutical companies that help them is a matter that warrants deeper reflection.

This paper reviewed some of the personal aspects of physicians, preferences and stigmatisation for IBS and IBD. The results indicate that although there is perceived stigmatisation for both pathologies, public stigmatisation (in this case medical) is much higher for IBS.

The fact is that many patients with FGID are frustrated because of a poor interrelationship with their doctors, whom they regard as not very empathetic or friendly27,33,34. The lack of knowledge of its pathophysiology, the absence of a specific diagnostic biological marker, the lack of curative treatment or the association with psychological disorders "delegitimise" it and contribute to the vicious circle of IBS: multiple and unnecessary tests, a vague diagnosis, repeat visits and poor results50. Moreover, the fact that certain emotional aspects have been involved in the pathophysiology of IBS has led many physicians, a certain portion of the population, and even some patients, to view it as a purely psychological disorder, with the consequent negative connotations51: "It's all in their head; they complain too much." Similarly, the use of antidepressants to treat IBS increases the syndrome's "bad reputation"52. At this point it should also be remembered that approximately 30% of patients with UC or CD suffer from depression or anxiety53, and that if the use of antidepressants is mistaken for a mental illness, it should also be borne in mind that 28% of IBD patients are on this therapy at some point during their illness54,55. Moreover, patients with depression have an increased risk of getting IBD56, and several studies have found that IBD patients' evolution improves when they take antidepressants57. In conclusion, our brain's influence on the bowel is not unique to IBS. The central nervous system can condition factors such as intestinal permeability, immune response, microbiota or inflammation and be central to the genesis and evolution of IBD58.

Finally, some professionals, especially gastroenterologists, may think that IBS is a more typical disorder of primary care than gastroenterology, but this is yet again a sign of stigmatisation. The complexity of its pathophysiology and the enormous diversity of its treatment make it necessary for the care of these patients, or at least a considerable number of them, to be in the hands of specialists who are deeply conversant with this condition.

There are undoubtedly several aspects that justify the clinical relevance and the need for specific IBD consultations (units). These include the existence of a surgical aspect of this pathology, requiring mixed consultations (medical-surgical), interdisciplinary committees and hospital admissions (standard and "day hospital")59. Additionally, intestinal resections, ileostomy and colectomy with reservoir prompt particular changes in quality of life derived from the type of disease60. Furthermore, in IBD, specific medical treatment involves very specialised monitoring, not only because specific personnel and resources (intravenous treatment with monitoring of levels) are required, but also because as a result of pharmacological immunosuppression patients are at greater risk of contracting infectious diseases, thus increasing clinical resources. Endoscopic treatments are not performed in IBS, whereas in CD this treatment is indicated for the dilation of stenotic segments61. Finally, a colorectal cancer (CRC) screening protocol is established in IBD because the risk, mainly in patients with pancolitis, is higher than in the general population, which has not been observed in IBS; the same applied to patients with IBD and sclerosing cholangitis62.

However, there are also arguments in favour of the need for specialised, multidisciplinary and complex monitoring in IBS cases. This includes its association with other challenging pathologies, such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple chemical sensitivity or interstitial cystitis63. In addition, the complex gut-brain interaction origin of IBS requires an in-depth knowledge of motility abnormalities, visceral hypersensitivity, intestinal mucosal/immune function, microbiota and central nervous system processing alterations64. Finally, the need for expertise in the use of drugs that act on the central nervous system65, not to mention the complexity of the dietary management of these patients66, makes the need for specialised units with collaborating gastroenterologists, psychologists and nutritionists essential.

In any case, it is not a question of "robbing Peter to pay Paul." Clearly, IBD deserves the attention and resources that it gets. The comparison between IBS and IBD is drawn solely to highlight the many deficits suffered by the former. Actions implemented to further and develop knowledge about IBD and its management should serve as an example and as a stimulus for IBS67.

In summary, following the comparison of several factors that determine the relevance and needs of IBS and IBD, it may be concluded that:

- 1

The prevalence of IBS is about 10-fold that of IBD and the number of medical visits is much higher.

- 2

The accompanying morbidity is very significant in both entities, and mortality (albeit low) is higher in IBD.

- 3

Quality of life is greatly altered in both IBS and IBD, and its impact is determined by symptom severity rather than by disease type.

- 4

The social and health impact is similar in both.

- 5

The number of teaching hours and personal resources devoted to IBD is approximately twice that of IBS (or FGID in general).

- 6

Public relevance is very high for both, and even greater for IBS, although the associative capacity is higher in IBD.

- 7

Medical stigmatisation is patent for IBS but not apparent for IBD.

In our opinion, in order to reduce this imbalance between human and material needs and resources in FGID, drastic changes are called for in educational aspects, communication skills, prioritization according to the demands of the patients, and the (personal and social) compensation for physicians.

Ethical considerationsSince no drugs or medical action were the subject matter of this article, no evaluation by an ethics committee was required.

FundingNo funding was received for this work.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.