Iron deficiency without anaemia (IDWA) is commonly found in outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in an even higher proportion than anaemia. However, its true prevalence and possible impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) are unknown. The objectives of this study were: to establish the prevalence of IDWA, identify possible associated factors and measure their impact on HRQoL.

Materials and methods127 patients with IBD in an outpatient setting were consecutively included in an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study. IDWA was defined as ferritin levels of <100ng/mL with inflammatory activity or ≤30ng/mL without it, with transferrin saturation of ≤16%, and with normal haemoglobin levels. HRQoL was assessed using two questionnaires: the IBDQ-9 for symptoms related to IBD and the FACIT-F to measure the presence of fatigue. Fatigue was considered extreme with a score of ≤30 points.

ResultsThe prevalence of IDWA was 37%. Variables associated with its occurrence were female gender (OR=2.9; p=0.015) and the presence of inflammatory activity (OR=9.4; p=0.001). Patients with IDWA presented HRQoL questionnaires with lower overall scores; decreases of 6.6 (p<0.001) and 4.3 (p=0.037) points in the IBDQ-9 and the FACIT-F were recorded, respectively. In addition, an increase of 29.4% in the presence of extreme fatigue was observed.

ConclusionThe prevalence of IDWA is considerable in outpatients with IBD. IDWA is associated with female gender and inflammatory activity. It has a clear negative impact on HRQoL. A more active approach is needed to treat this complication.

El déficit de hierro sin anemia asociada (DHSA) es un hallazgo frecuente en los pacientes no ingresados con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII), incluso en mayor proporción que la anemia. Sin embargo, no existen datos concluyentes de su presencia en nuestro medio ni del posible deterioro que conlleva en la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS). Los objetivos de este trabajo fueron: establecer la prevalencia del DHSA, identificar posibles factores asociados y medir su impacto en la CVRS.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron 127 pacientes con EII, de manera consecutiva, en medio extrahospitalario en un estudio observacional, descriptivo, de corte transversal. Se definió DHSA como niveles de ferritina ≤30 ng/ml en ausencia de actividad inflamatoria o <100 ng/ml en su presencia, con índice de saturación de transferrina ≤16%, junto a niveles normales de hemoglobina. Se evaluó la CVRS mediante dos cuestionarios: CVEII-9 para los síntomas relacionados con EII, y FACIT-F para medir la presencia de fatiga, considerándola extrema ante una puntuación ≤ 30 puntos.

ResultadosLa prevalencia del DHSA fue del 37%. El sexo femenino (OR=2,9; p=0,015) y la presencia de actividad inflamatoria (OR=9,4; p=0,001) fueron las variables asociadas con su aparición. Los pacientes con DHSA presentaron cuestionarios de CVRS con menores puntuaciones de forma global; registrando una caída de 6,6 (p<0,001) y 4,3 (p=0,037) puntos en CVEII-9 y FACIT-F, respectivamente. Además, se observó un incremento en la presencia de fatiga extrema del 29,4%.

ConclusiónLa prevalencia de DHSA es considerable en los pacientes con EII en el ámbito extrahospitalario. Se asocia al sexo femenino y a la actividad inflamatoria, y supone un claro impacto negativo en la CVRS. Es necesaria una actitud más activa para el tratamiento de esta complicación.

Anaemia is the most common extraintestinal manifestation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),1–3 with symptoms such as asthenia and chronic fatigue which affect patient functionality. Its management has become significantly more relevant in the last decade, with specific clinical guides being developed.4–6

Non-anaemic iron deficiency (NAID) is defined as insufficient iron deposits, as well as low levels of ferritin and a low transferrin saturation index (TSI), with normal levels of haemoglobin (Hb). Few studies analyse the significance of its occurrence in IBD, focusing only on the anaemia aspect. The prevalence of NAID in the series published ranges between 36% and 90%.7–10

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a concept involving aspects relating to the physical and psychological spheres, and the subjective perception of the state of health.11 Its measurement is essential in IBD because it reflects an important aspect of the patients’ reality. Nevertheless, its quantification is not easy, and so specific questionnaires have been developed. These include the FACIT-F questionnaire,12 which measures the level of fatigue, and the IBDQ-9, for symptoms related to IBD itself.13

Fatigue is defined as the subjective perception of tiredness involving a deterioration in mental and physical functioning. Although it is frequently mentioned in patients with IBD, its actual prevalence is not well established in our setting. Various studies have attempted to establish keys for detecting it, estimating its prevalence and identifying the associated factors.14 The majority only analyse the spectrum of patients with anaemia, where the direct link between anaemia and the negative impact on HRQoL is known. However, it is unknown whether NAID plays an important role. Although a recent study15 confirms this link, the evidence is scarce and results are often contradictory, disparate or incomplete.16,17 The data available are not sufficient to establish an active treatment indication for NAID, although it could be a therapeutic objective with which an improvement in HRQoL is achieved.

This study was proposed in an attempt to provide information on this specific issue. The main objective was to determine the prevalence of NAID in patients diagnosed with IBD in the outpatient setting. The secondary objectives were to identify the associated factors and the impact on the patients’ perceived HRQoL. Finally, the therapeutic management was reviewed in light of its detection by the relevant doctor.

Materials and methodsPatientsThis is a descriptive, observational, cross-sectional study. A sample of 127 consecutive patients diagnosed with IBD, according to the international diagnostic criteria,18,19 was enrolled in outpatient follow-up in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease unit at Hospital Reina Sofía de Córdoba (Spain) between April and June 2015. The patients included were of legal age, who, after being briefed, granted their consent. Patients under 18 and over the age of 70 were excluded, as were those with any of the following clinical conditions: pregnancy, neoplastic or haematological diseases, chronic kidney failure and haemolytic anaemia. The good clinical practice guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki20 were followed.

The patients previously did a blood test that included a complete blood count, iron metabolism, and vitamin B12 and folic acid levels in order to evaluate the existence and possible causes of anaemia/iron deficiency, as well as C-reactive protein (CRP), as a reactant in the acute phase, to detect the presence of inflammatory activity. At the time of the in-person doctor–patient interview, the signs and symptoms were recorded in the digital clinical history, highlighting those that were associated with IBD. Two questionnaires were provided: FACIT-F12 to evaluate fatigue and IBDQ-913 for the quality of life linked to the IBD itself, completed under the supervision of nursing staff. Finally, the therapeutic approach for either anaemia or iron deficiency taken by the doctor responsible was recorded.

Inflammatory activityThe presence of symptoms related to an IBD outbreak (increase in the number of bowel movements, abdominal pain, etc.) and/or evidence of endoscopic and/or radiological lesions in the three months prior to the patient evaluation, together with abnormal test results (CRP>5mg/dL) were identified as being clinically compatible symptoms.

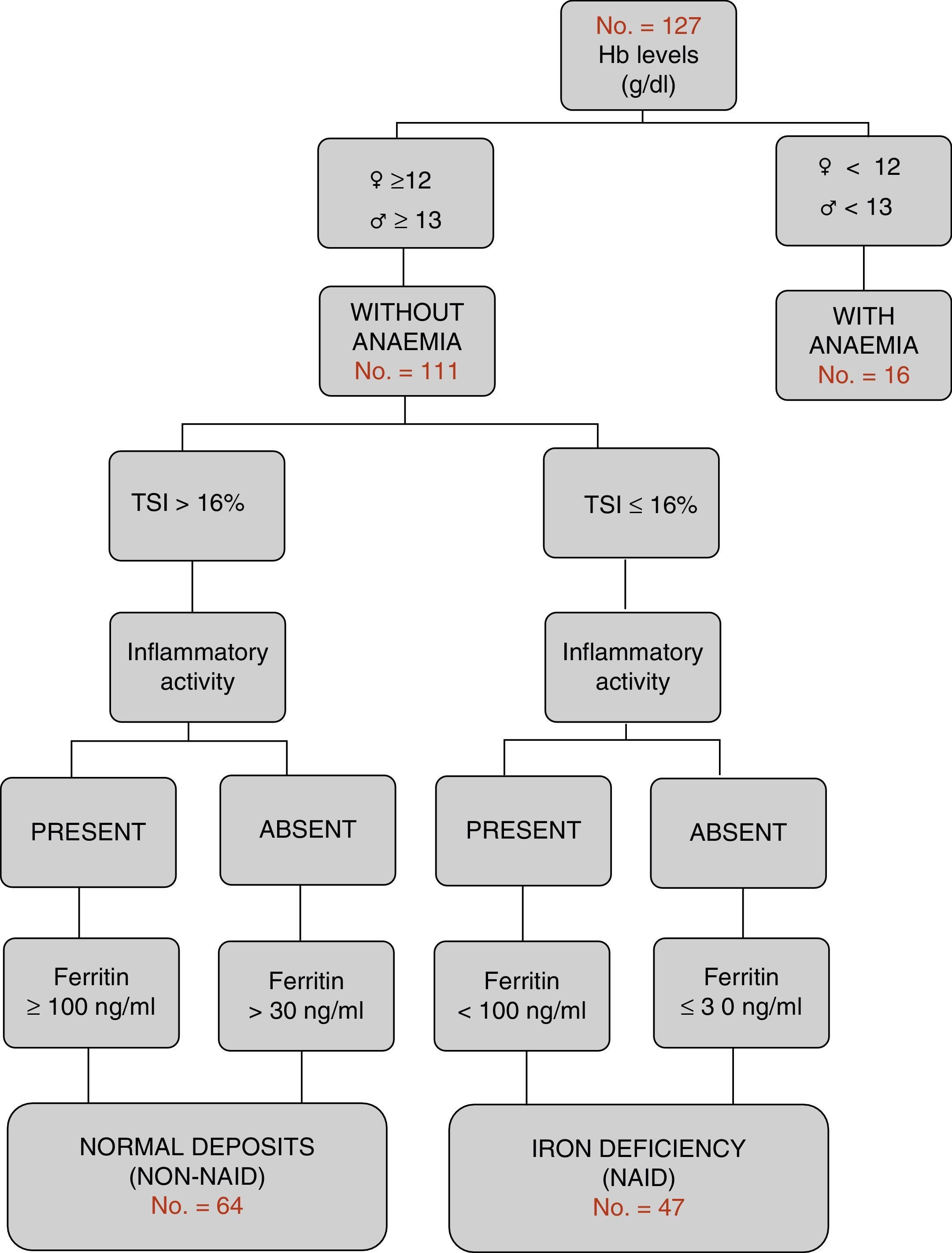

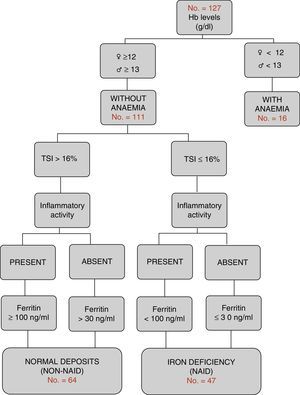

Definition of the different groups in relation to iron metabolismAccording to the WHO international criteria,21 Hb values <12g/dL in women and <13g/dL in men are classified as anaemia. According to the criteria of the most recent European consensus,6 NAID is defined as a condition in which ferritin levels are less than or equal to 30ng/L in the absence of inflammatory activity, or <100ng/dL where it is present, with normal haemoglobin levels and a TSI<16% (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the consumption of oral or intravenous iron in the last six months was recorded (excluding patients on active treatment).

Evaluation of health-related quality of lifeThe Spanish version of the FACIT-F questionnaire,12 which has been internationally validated and standardised, was used to analyse the subjective impact of the possible onset of fatigue in the study patients. This questionnaire consists of 13 questions, measured using a Likert scale, with a final score of 0–52 points, inversely proportional to the level of fatigue. A score less than or equal to 30 points was considered extreme fatigue. The Spanish version (CVEII-9) of the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) was used to evaluate quality of life linked to the symptoms of the IBD itself.13 This questionnaire consists of nine questions with responses graded using a seven-point scale, where seven represents the best function and one represents the worst, with a possible range of 9–63 points. The direct score is obtained by adding together the score for each of the items concerned, and is transformed using a specific table for obtaining a final score of 0–100 points; the lower the score, the lower the quality of life and vice versa.

Statistical analysis and calculation of the sample sizeVersion 20.0 of the IBM SPSS® (IBM Corporation) software for MAC was used. First, a descriptive analysis was conducted where the qualitative endpoints were measured using percentages to express the proportions and frequencies observed. For the quantitative endpoints, the arithmetic mean and standard deviation were calculated for endpoints with a normal distribution, and the median and interquartile range were calculated for the others. A comparative analysis was then conducted between the two patient groups without anaemia according to whether they had iron deficiency (NAID group) or not (non-NAID group). An initial univariate analysis was conducted using the specific tests for each endpoint (Student's t-test for quantitative endpoints, chi-squared test for qualitative endpoints), with a level of significance where p<0.05. Finally, a multivariate analysis was conducted to identify which endpoints were associated with a greater prevalence of NAID using an associative model through multiple logistic regression, controlling the possible interactions and confounders. The sample size was calculated using the EPIDAT22 programme, taking 1500 patients as the reference population. Considering an expected prevalence of 75%, with a 95% confidence interval, the minimum sample necessary was 118 patients.

ResultsGeneral characteristicsA total of 127 patients were included. The patients were predominantly male (58.3%). The average age was 42.3±12.1 years. The most common type of IBD was Crohn's disease (61.4%), with 78 patients, which was predominantly ileocolic (47.4%), presenting an inflammatory pattern (B1) (64.1%). The remainder presented with ulcerative colitis (UC), which was the most common widespread disorder (46.9%). Inflammation was present in 21.3% at the time of outpatient evaluation. Only 10.2% of patients required hospital admission for IBD in the previous three months.

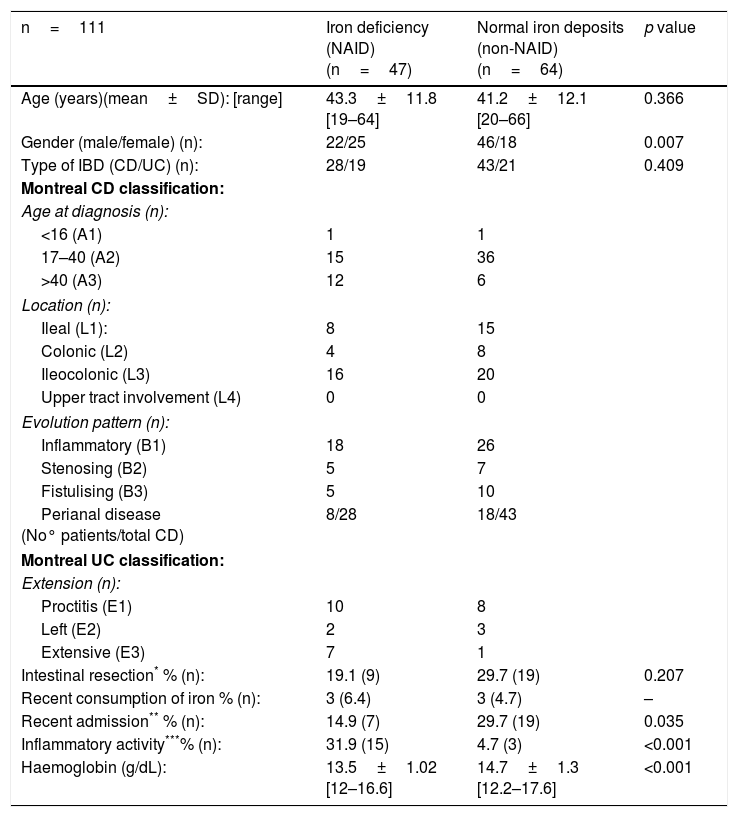

Characteristics according to groups by complete blood count and iron metabolismOnly 16 of the 127 patients (12.6%) presented with anaemic values at the time of the study. Iron deficiency was the main cause (10 out of the 16 patients). Non-anaemic patients (n=111) were classified according to the algorithm in Fig. 1: iron deficiency or NAID group (n=47), and with normal deposits or non-NAID group (n=64). The overall prevalence of NAID was established at 37%. When the groups were compared, no differences were found in the distribution in terms of age, type of IBD, location or evolution pattern. However, the NAID group had lower levels of Hb (13.5g/dL vs 14.7g/dL; p<0.001), included a higher percentage of women (53.2 vs 28.1, p<0.007) and presented with inflammatory activity (31.9 vs 4.7%, p<0.001) and a lower rate of recent hospital admission (14.9 vs 29.7%, p=0.007). The other endpoints compared are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of non-anaemic patients, classified by group according to whether they have iron deficiency (univariate analysis: comparison of averages and proportions).

| n=111 | Iron deficiency (NAID) (n=47) | Normal iron deposits (non-NAID) (n=64) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)(mean±SD): [range] | 43.3±11.8 [19–64] | 41.2±12.1 [20–66] | 0.366 |

| Gender (male/female) (n): | 22/25 | 46/18 | 0.007 |

| Type of IBD (CD/UC) (n): | 28/19 | 43/21 | 0.409 |

| Montreal CD classification: | |||

| Age at diagnosis (n): | |||

| <16 (A1) | 1 | 1 | |

| 17–40 (A2) | 15 | 36 | |

| >40 (A3) | 12 | 6 | |

| Location (n): | |||

| Ileal (L1): | 8 | 15 | |

| Colonic (L2) | 4 | 8 | |

| Ileocolonic (L3) | 16 | 20 | |

| Upper tract involvement (L4) | 0 | 0 | |

| Evolution pattern (n): | |||

| Inflammatory (B1) | 18 | 26 | |

| Stenosing (B2) | 5 | 7 | |

| Fistulising (B3) | 5 | 10 | |

| Perianal disease (No° patients/total CD) | 8/28 | 18/43 | |

| Montreal UC classification: | |||

| Extension (n): | |||

| Proctitis (E1) | 10 | 8 | |

| Left (E2) | 2 | 3 | |

| Extensive (E3) | 7 | 1 | |

| Intestinal resection* % (n): | 19.1 (9) | 29.7 (19) | 0.207 |

| Recent consumption of iron % (n): | 3 (6.4) | 3 (4.7) | – |

| Recent admission** % (n): | 14.9 (7) | 29.7 (19) | 0.035 |

| Inflammatory activity***% (n): | 31.9 (15) | 4.7 (3) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL): | 13.5±1.02 [12–16.6] | 14.7±1.3 [12.2–17.6] | <0.001 |

Student's t-test to compare the averages and chi-squared test to compare proportions (Fisher's exact test for n<10).

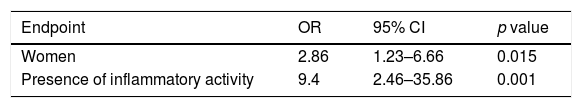

In the multivariate analysis, the factors associated with the onset of NAID were: female gender, with an OR=2.9 (1.2–6.7; CI 95%) (p=0.015), and presence of inflammatory activity (compared to its absence), with an OR=9.4 (2.5–35.9; CI 95%) (p=0.001). Recent hospital admission had an OR=4.7 (0.9–26.5; CI 95%), without achieving statistical significance (p=0.07) (Table 2).

Endpoints related to the presence of NAID (multivariate analysis).

| Endpoint | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 2.86 | 1.23–6.66 | 0.015 |

| Presence of inflammatory activity | 9.4 | 2.46–35.86 | 0.001 |

NAID, non-anaemic iron deficiency.

Multivariate analysis according to multiple logistic regression model.

Likelihood ratio test=21.387; p<0.001; Degree of Freedom (DOF)=2.

Goodness-of-fit (Nagelkerke R2=0.236). Area under the ROC curve=0.720.

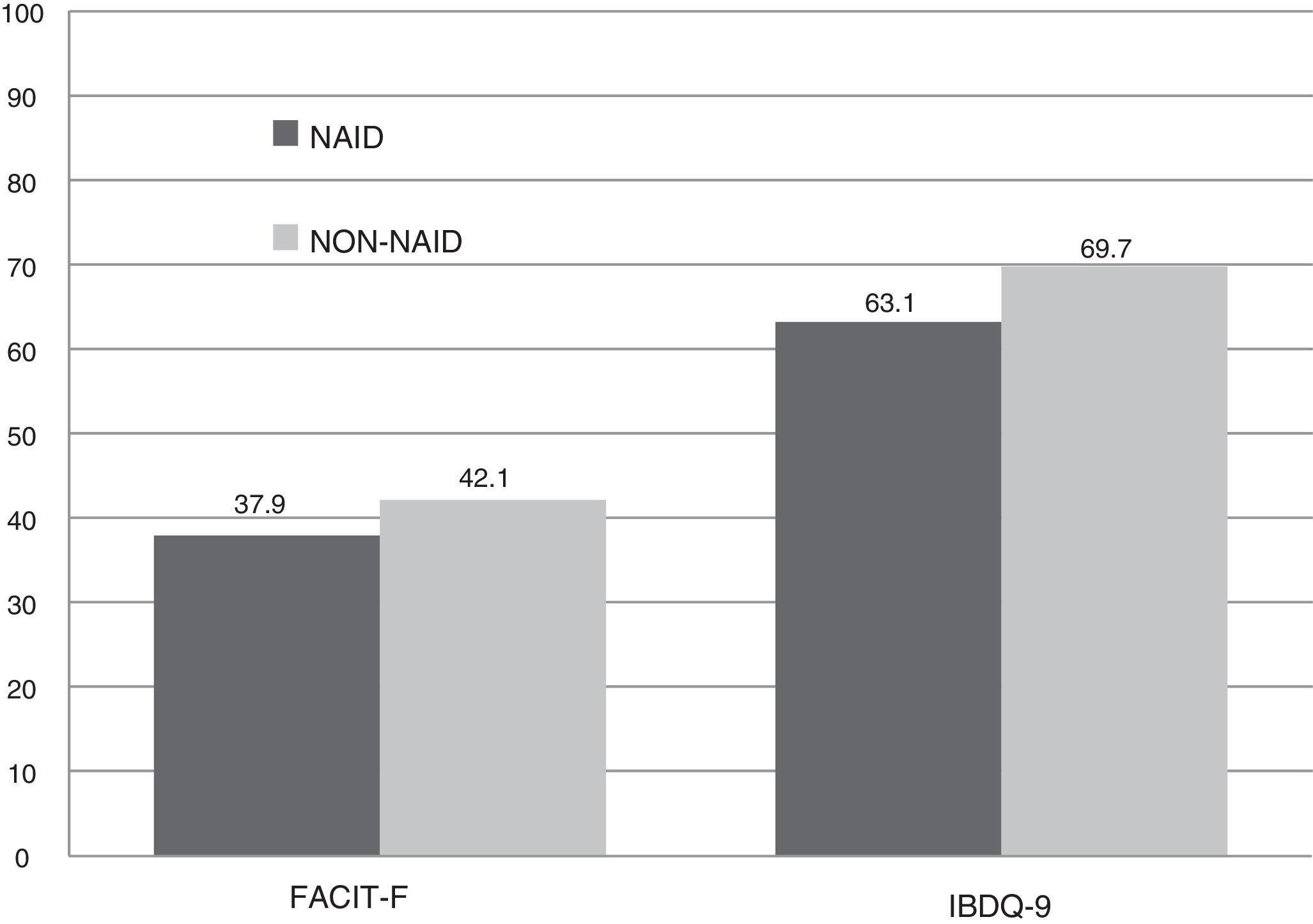

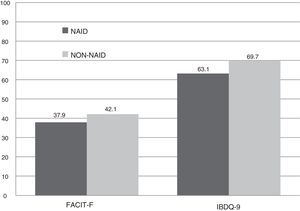

The scores recorded were significantly lower in the NAID group compared with the non-NAID group. In IBDQ-9, there was a drop of almost seven points, leading to a significant difference (63.2 vs 69.7 points, p<0.001). A lower overall score was recorded in the FACIT-F questionnaire (37.9 vs 42.2 points; p=0.037). This was due to a greater prevalence of extreme fatigue (64.7%), with a median of 22 points, compared to the patients with no iron deficiency (35.3%), with a median of 45 points, without reaching statistical significance (p=0.069) (Fig. 2).

Doctors’ approach to non-anaemic iron deficiencyAn active approach was taken in 11 of the 47 patients: treatment with oral iron (n=3), advice regarding an iron-rich diet (n=5) and multivitamin supplements (n=6). Therapeutic abstention was the most common approach in 70.2% of patients with NAID (n=33).

DiscussionThe prevalence of NAID detected in this study was 37%. Female gender and presence of inflammatory activity were the factors most associated with developing this complication, which had a negative impact on the patients’ perceived quality of life.

Few studies analyse the actual prevalence of NAID itself. Figures of around 36–90% have been estimated.8–10 This wide range is due to the heterogeneity of the populations studied (outpatients or admitted patients, recently diagnosed or over the course of their illness), the actual definition of iron deficiency and the year the studies were published.7–10 Figures similar to those of our study were recorded in a Hungarian cohort of 254 patients.23 In their study on a Scandinavian population, Bager et al.14 reported a rate of 34%.

To define the groups in our study, we took the clinical practice guides published by Gasche et al.4 and the Belgian Society,5 subsequently agreed upon by the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation,6 as our reference. Serum ferritin is an accessible measurement in determining iron deposits. Although there is no clear consensus on the definition of appropriate levels, it is considered that a cut-off point of <30ng/mL for deficiency and >100ng/mL to exclude can ensure a sensitivity and specificity of 92% and 98%, respectively.24

The origin of anaemia in IBD is complex and multifactorial. In 90% of cases the underlying cause is iron deficiency. To date, the associated factors include diagnosis at an early age, diagnosis or hospitalisation in the last six months, presence of inflammatory activity and Crohn's disease in light of UC.9,10 If we consider non-anaemic iron deficiency a previous deficiency, it would be logical to assume that the associated factors are the same. However, this assertion has not been proven.17 In our analysis, the following factors were found to be associated with the NAID group. First, lower Hb values were observed. This finding seems to reinforce the assumption that NAID is a “pre-anaemic” state; more active monitoring could therefore be recommended in this subgroup of patients. Second, it is more prevalent in women, which is in line with the evidence published. The last associated factor was the presence of inflammatory activity. This discovery could be explained by an increase in the levels of circulating cytokines and interleukins, where iron is an essential element, and which would therefore involve greater consumption.24

The concept of HRQoL has become significantly more relevant in the last decade. It can be seen to be influenced by multiple factors: symptoms associated with the persistence of inflammatory activity and the incapacity that comes with it; the need for chronic treatments and respective adherence to these; and the need to regularly undergo invasive tests, such as colonoscopy.11 Detecting and treating the onset of fatigue is fundamental because it is a common symptom in patients with chronic diseases and it is known to be linked to a worse perceived quality of life.25 It is generally accompanied by symptoms such as weakness, insomnia, irritability and mood swings.26 Its presence affects the daily life of patients, especially professionally, where it can be a cause of absenteeism. We have attempted to establish the origin of fatigue, and we believe it is a complex interaction of multiple factors, among which anaemia stands out.14 It is not clear whether the presence of NAID itself contributes to fatigue. Goldenberg et al. did not manage to prove this17 even though they acknowledged a lack of statistical power. Other, more recent studies, such as that published by Herrera de-Guise et al., did report a correlation between NAID and a negative impact on HRQoL.15 Through the objective analysis of the scores obtained in the questionnaires, this study has managed to show the direct relationship between NAID and a worse HRQoL, as perceived by patients.

Iron, an essential element, plays a role in multiple functions, such as the capacity for physical effort and as a neurotransmitter that maintains cognitive abilities such as learning and memory.24 There are no conclusive studies that clarify whether treatment for iron deficiency, in the absence of anaemia, leads to an improvement in symptoms such as fatigue or chronic tiredness in the context of IBD. This aspect has been reported in non-anaemic women suffering from fatigue that cannot be explained by any other cause.27 Anker et al. have shown an improvement after ferric carboxymaltose infusion in patients with heart disease and iron deficiency.28 In 2013, the FERGIMAIN study29 monitored patients who previously suffered from anaemia over an eight-month period, observing recurrence rates of 40%. An active approach was taken, administering a preventive dose of intravenous iron for ferritin levels under 100ng/dL, regardless of the anaemic condition. This action managed to reduce the recurrence of anaemia to 26.7%.

Our study reflects the most widespread clinical approach currently in use—therapeutic abstention in most cases—most likely due to a lack of evaluation for this complication in the overall context of our patients. To improve the perceived quality of life and to avoid a possible anaemic relapse, it seems that a more active approach is justified. Controlled, prospective, cost-effective studies that examine this aspect in greater detail are required.

Regarding the main limitations, it should be noted that given the cross-sectional design, with no follow-up period, causal relationships could not be established. Neither was a subanalysis conducted on pre- and post-menopausal women or those with a gynaecological disorder, which could explain a greater occurrence of NAID in this group. Lastly, faecal calprotectin, the most accurate marker of inflammatory activity, was not used.

This study shows that the prevalence of non-anaemic iron deficiency is greater than one third in patients with IBD at an outpatient setting. It is more prevalent in women and those with an underlying inflammatory activity, and it involves a clear impairment in the quality of life of the patients affected. Stricter monitoring, and even an active therapeutic approach, are recommended in order to detect its onset. Future prospective studies should examine the possible benefits in greater detail.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: González Alayón C, Pedrajas Crespo C, Marín Pedrosa S, Benítez JM, Iglesias Flores E, Salgueiro Rodríguez I, et al. Prevalencia de déficit de hierro sin anemia en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal y su impacto en la calidad de vida. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:22–29.