In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), diet can be perceived as a trigger for relapses or clinical worsening, dietary modifications are frequent and not derived from professional advice. The aim of this study was to evaluate the perception of the need for dietary advice in patients with IBD, to know the dietary modifications adopted and, it’s effect on IBD.

MethodsAn anonymous structured questionnaire with a visual analog scale (0–10) was distributed to consecutive outpatients from our IBD unit.

ResultsA total of 124 complete the questionnaire (54% ulcerative colitis, 46% Crohn’s disease). Mean age was 47 ± 12 years. Dietary advice provided in the clinic was assessed with a median score of 7 (IIC, 4.50–9.00). 40% sought external dietary advice, often during the first year after diagnosis (70%). The most frequent dietary recommendations from an external professional were: dairy free diet (29%), low fat (27%), gluten free (23%), and low fiber (21%). Dietary advice from external source was assessed with a median score of 7.50 (IIC, 5.50–9.50), improving digestive symptoms in 73% of cases. Regarding dietary modifications, 61% excluded some foods (57% permanently) and 11% fasted on their own decision.

ConclusionsIBD patient show a clear need for dietary advice, especially at the time of IBD diagnosis. Early specific and in-depth dietary information would increase patient satisfaction and could prevent the adoption of unjustified exclusion diets.

En la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII), la dieta puede percibirse como un desencadenante de recidivas o empeoramiento clínico, siendo frecuentes las modificaciones dietéticas no derivadas de asesoramiento profesional.

ObjetivosEvaluar la percepción de necesidad de asesoramiento dietético en pacientes con EII, conocer las modificaciones dietéticas y su efecto sobre la EII.

MétodosSe invitó a participar anónima y consecutivamente durante 3 meses a todos los pacientes visitados en consulta de EII y los pacientes en hospitalización de día durante la administración de fármacos biológicos, a rellenar un cuestionario estructurado con escala visual analógica (0–10).

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 124 encuestas (54% colitis ulcerosa, 46% enfermedad de Crohn). La edad media fue de 47 ± 12 años. El asesoramiento dietético impartido en consulta se valoró con una mediana de 7.0 (IIC, 4,50−9,00). El 40% buscó asesoramiento dietético externo, frecuentemente en el primer año tras el diagnóstico (70%). Estas recomendaciones externas fueron: dieta sin lácteos (29%), baja en grasas (27%), sin gluten (23%) y baja en fibra (21%). La ayuda percibida externa se valoró con mediana de 7,50 (IIC, 5,50−9,50), con mejoría percibida de la sintomatología digestiva (73%). El 61% excluyó algún alimento (57% permanentemente) y 11% realizó ayuno por iniciativa propia.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con EII muestran una clara necesidad de asesoramiento dietético, especialmente en el diagnóstico. Una información dietética precoz, específica incrementaría su satisfacción y evitaría la adopción de dietas de exclusión no justificadas.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterised by chronic activation of the intestinal immune system, probably as a result of the interaction between genetic and environmental factors, such as smoking and infections1 which, when added to others such as diet or pollution, lead to dysregulation of different immune response pathways, with the resulting damage to the bowel.

Diet is probably one of the few factors (along with smoking) which can easily be changed and viewed positively by patients. However, there is little evidence on the role diet plays in the development and disease course of IBD. Recent studies have shown how nutrition can play a crucial role in regulating the immune system through specific compounds, such as salt, an excess of which can affect the innate immune system by inducing the expression of IL-17A in naïve CD4 cells,2 and in modulating the activity of the gut microbiota. Diet has a direct effect on the composition of the microbiota, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Numerous studies have shown that the microbiota of patients with IBD is different from that of healthy people.3–5 It has also been reported that societies with a higher consumption of dietary fiber have a lower incidence of inflammatory diseases.6,7 This means a higher incidence of IBD in developed countries compared to underdeveloped countries2, and an increase in the incidence after the adoption of western lifestyles in countries with previously lower rates.8–11 This all suggests that diet may play a role in the pathogenesis of the inflammation.8,10–12

In the clinical sphere, IBD has periods of remission alternated with periods of inflammatory activity. However, up to 35% of IBD patients have gastrointestinal symptoms even when they are in remission.13 The aetiology of these symptoms is multifactorial and very often involves patients excluding or restricting certain eating behaviours in order to improve their symptoms. Of all the environmental aspects associated with IBD, from the patients' perspective, eating habits are a trigger for relapses of the disease.8 In a British study, up to 50% of patients with IBD perceived that diet was a triggering factor for their disease, and 57% considered dietary factors could precipitate a recurrence.14 In clinical practice, it is clear that patients associate some of their symptoms and/or relapses with certain foods, and the diet or type of food they should eat is a common and repeated topic of consultation.15 However, it is difficult to make firm evidence-based recommendations and that results in patients seeking information from other sources. These sources may be misleading or confusing and prompt them to make dietary changes which can often be detrimental to their nutritional health.14

We decided to conduct this study to find out the actual need for dietary advice and determine the possible dietary modifications, and the perceived benefits.

Patients and methodsFrom March to June 2019, all patients who attended either for a follow-up visit at a specialised IBD clinic or for the administration of biological therapy as a day hospital patient were consecutively invited to take part in an anonymous survey without the presence of the physician. As the patient had to complete the survey personally after an explanation of the study, all participants were considered to have given their informed consent. The survey consisted of a structured questionnaire with 14 questions (Table 1), which included sociodemographic variables (age, gender, educational level), clinical-epidemiological variables (smoking, type of IBD, treatment for IBD, history of previous diagnosis of food intolerance) and variables relating to satisfaction with the information received about diet and IBD (using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 [dissatisfied] to 10 [very satisfied]). It also asked about the need to seek dietary advice outside the centre; when the answer was affirmative, the patient had to answer questions about when they had sought it (during inactive disease, in a flare-up, or after surgery), in relation to when they were diagnosed (coinciding with the diagnosis, six months to 12 months after diagnosis, or beyond three years), what type of professional they consulted, what type of diet was recommended and how long they followed it for. The impact of dietary changes was also assessed in relation to gastrointestinal symptoms, the feeling of fatigue and night-time rest. Lastly, they were asked about the voluntary exclusion of food (what type of food, and whether it was temporary or permanent) and the practice of fasting.

| 1. Have you been diagnosed with any type of food intolerance (for example to lactose, gluten, sorbitol)? |

| 0. No 1. Yes |

| 2. How would you rate the information about diet you have received from the doctor who is looking after your inflammatory disease? Mark with a score on the line, minimum = bad (0) and maximum = very good (10) |

| ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

| Minimum Maximum |

| 3. Do you think your diet makes your symptoms worse? |

| Mark with a score on the line, minimum = bad (0) and maximum = very good (10) |

| ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

| Minimum Maximum |

| 4. Have you sought dietary advice outside of the hospital clinic where they look after your inflammatory disease? |

| 0. No 1. Yes |

| a. If you have sought dietary advice, when was it? |

| 0. When your inflammatory disease was inactive or under control |

| 1. When you were having a flare-up |

| 2. After surgery for your inflammatory disease |

| 3. Another time:…………………………………………………………… |

| b. Have you sought dietary advice in relation to the diagnosis of your inflammatory disease? |

| 1. Coinciding with the diagnosis of your inflammatory disease (first 6 months) |

| 2. From 6 months to a year |

| 3. More than 3 years |

| c. What type of professional have you received dietary advice from? |

| 1. Dietitian/nutritionist from the hospital I attend |

| 2. Private dietitian/nutritionist |

| 3. Doctor currently looking after your inflammatory disease |

| 4. Any other doctor |

| 5. Nurse |

| 6. Other:…………………………………………………. |

| d. What was the dietary recommendation? |

| 1. Dairy-free diet |

| 2. Gluten-free diet |

| 3. Low-fiber diet |

| 4. Vegetarian diet |

| 5. Diet excluding animal proteins |

| 6. Sugar-restricted diet (for example fruits/vegetables) |

| 7. Low-fat diet |

| 8. Low-carbohydrate diet |

| 9. Astringent diet |

| 10. Other:……………………………………………………………………………………… |

| e. For how long have you been following these recommendations? |

| 1. Less than 6 months |

| 2. From 6 months to a year |

| 3. Between 1 and 2 years |

| 4. Over 2 years |

| f. Do you think these dietary recommendations have helped you? |

| Mark with a score on the line, minimum = bad (0) and maximum = very good (10) |

| ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

| Minimum Maximum |

| g. How have they helped you (tick more than one if applicable)? |

| 1. Improvement in digestive symptoms |

| 2. Improvement in feeling of tiredness |

| 3. Improvement of night-time rest |

| 4. Other:………………………………………………………………………………. |

| 5. Do you think it is necessary for the control of your disease to have a dietary consultation as part of the hospital team that looks after you? |

| Mark with a score on the line, minimum = bad (0) and maximum = very good (10) |

| ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

| Minimum Maximum |

| 6. Have you decided on your own initiative to exclude foods from your diet as a result of the diagnosis/course of your inflammatory disease? |

| 0. No 1. Yes |

| a. What foods have you excluded?…………………………………………………… |

| b. Have you excluded it permanently? |

| 0. No 1. Yes |

| c. Have you excluded it temporarily (<6 months)? |

| 0. No 1. Yes |

| 7. Have you ever had a period of fasting from solid foods? |

| 0. No 1. Yes |

| a. If you have fasted, has it been on a regular basis (for example annually, six-monthly)? |

| 0. No 1. Yes |

Categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequencies (%); quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). The rating scales are expressed as median and interquartile index (intensity composite index - ICI). The χ2 test was used to analyse qualitative variables, while Student's t-test was used for quantitative variables. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

ResultsA total of 124 surveys were obtained, 46% of which were from patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and 54% with ulcerative colitis (UC), with 50% being female. The mean age at diagnosis of IBD was 33 ± 4.07 years; 41% had completed secondary school and 44% university studies. The mean age at the time of the survey was 47 ± 12.50 years and the mean time since onset of IBD was 13 ± 9.86 years; 19% of the participants were active smokers. With regard to IBD treatment, 54% were on biological therapy, 10% immunomodulatory therapy, 25% mesalazine, and the rest on no treatment. Nine percent reported some diagnosed food intolerance.

The dietary advice given by the doctor was rated and obtained a median score of seven (ICI, 4.50–9.00); 40% reported having sought outside dietary advice, 45% in the first six months after diagnosis, 25% six to 12 months after, and 25% after three years. From the IBD activity perspective, 60% of the cases sought advice while their IBD was active, while 20% inactive, and 8% after surgery for IBD. Twelve percent of respondents sought outside dietary advice for other reasons unrelated to IBD. Asked about the professional who provided the outside dietary advice, in 36% of the cases it was a nutritionist/dietitian working in the private sphere, in 26% their physician of reference for their IBD, in 10% the hospital dietitian/nutritionist, and 28% went to other professionals (qualified or not).

Of the outside dietary recommendations, there were essentially four reported with a similar frequency: dairy-free (29%), low-fat (27%), gluten-free (23%) and low-fiber (21%) diets. These recommendations were followed for a minimum of 12 months by 53% of patients. Regarding the exclusion of some food or food group, 61% of the patients acknowledged having excluded something, the most common being dairy products (26%), vegetables (16%), gluten (15%) and fats (8%), with permanent exclusion of the food in 57% of the cases. The perceived help from outside dietary advice, assessed using a visual analogue scale, obtained a median score of 7.5 (ICI, 5.50–9.50), with a perceived improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms in 73% of cases, and tiredness in 9%. Lastly, 11% of the patients acknowledged having fasted for therapeutic purposes, 38% of them periodically.

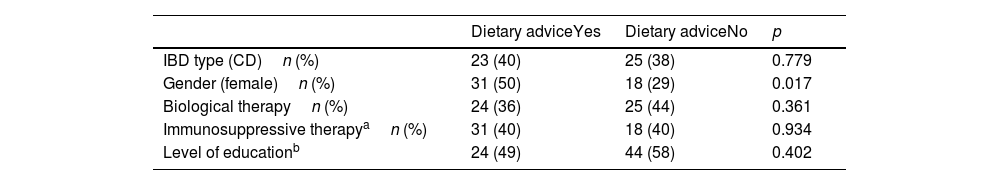

When analysing different factors associated with seeking outside dietary advice, the only statistically significant association was with being female (Table 1). In connection with medical treatment, 49% of those receiving biological therapy sought advice, followed by patients on treatment with mesalazine (25%), and to a much lesser extent those on immunosuppressive therapy (only 14%). Only 12% of patients on no treatment sought dietary advice. Table 2 also shows the differences between the patients who were on biological therapy and those who were not, and the patients on immunosuppressive or biological therapy and the patients not on either of these two drug groups. Neither current age (no search vs search: 47.8 ± 13.69 vs 46.1 ± 10.47, p = 0.489), age at diagnosis of the disease (34.2 ± 14.56 vs 32.2 ± 13.4, p = 0.412) or time since onset (13.60 ± 9.53 vs 14.38 ± 10.48, p = 0.673) showed significant association with seeking dietary advice.

Factors associated with seeking outside dietary advice.

| Dietary adviceYes | Dietary adviceNo | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBD type (CD)n (%) | 23 (40) | 25 (38) | 0.779 |

| Gender (female)n (%) | 31 (50) | 18 (29) | 0.017 |

| Biological therapyn (%) | 24 (36) | 25 (44) | 0.361 |

| Immunosuppressive therapyan (%) | 31 (40) | 18 (40) | 0.934 |

| Level of educationb | 24 (49) | 44 (58) | 0.402 |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; CD: Crohn's disease.

The aim of treatment for IBD is to restore quality of life either through drugs or surgery. Despite the broad range of therapies available these days, from the classic steroids and thiopurine immunosuppressants to selective biological or chemically-synthesised immunosuppressive agents, normal quality of life cannot always be achieved in all patients, and there is often a large gap between the patient's assessment and that of the physician.16–19 Even though it has not been demonstrated that any food can trigger a flare-up of IBD, patients tend to associate their gastrointestinal symptoms with the food they have recently eaten14,15,20,21 often leading them to exclude certain foods, sometimes permanently, with the consequent risk of inducing malnutrition or worsening their nutritional status.22–24

IBD-associated malnutrition is usually multifactorial. Although inflammatory activity is the main cause, it can also be aggravated by the associated anorexia and abdominal pain, fasting for diagnostic tests and inappropriate dietary changes. Malnutrition has been associated with a poorer response to medical treatment, a higher postoperative complication rate, longer hospital stays and decreased quality of life.23 The healthcare professional therefore has a crucial role in providing nutritional advice and management in this scenario.24,25 Moreover, patients give great importance to diet, perhaps due to the rise and popularity of "natural" therapies and how reasonable and easy it can seem to manage a gastrointestinal disease through easy-to-apply dietary changes, and they often ask for information on the subject. Despite all this, clinical practice guidelines and consensus documents only include generic recommendations, focusing almost exclusively on the nutritional approach to patients in a severe hospital outbreak, with few recommendations for the rest of the clinical scenarios, apart from strictures.26,27 An analysis of our patients’ perception of the quality of dietary information obtained a median score of 7.00 (ICI, 4.50–9). This may be considered sufficient, but there would seem to be an obvious margin for optimisation in this field. In a recent study carried out in our setting, Casanova et al.24 found that only half of the patients had received dietary advice compared to 73% reported in a British study28 but 33% in a French study.29 Vries et al.21 found that more than half of the patients received nutritional information from their gastroenterologist, although 70% stated that they would like more, and in fact, 50% of patients give the same weight to diet as to medical treatment.30 Interest in dietary advice was expressed by 90% of Spanish patients24 and 67% in a British study.14 These figures show their concern about this aspect, with 40% of the patients surveyed seeking outside dietary advice. Our results are also in line with other studies in that although patient demand for nutritional advice is high, the information received is low,23 and in the patient perception that the doctors do not have enough time.14,31

As for dietary restrictions, rates of 65% have been reported24; in our study 61%, with 57% of the cases applying these restrictions on a permanent basis. Regarding dietary changes, few have been shown to really be effective in IBD. A diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) reduces the symptoms in a large proportion of IBD patients,32 particularly in the management of persistent intestinal symptoms in patients with inactive IBD.13 However, the review by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation states that only two of these diets have been shown to reduce inflammatory parameters: the Specific Carbohydrate Diet, which eliminates sugars, processed foods, preservatives, all grains, starchy vegetables and dairy products; and the CD exclusion diet, which eliminates gluten, dairy products, processed foods, sugars, and red meat.27 In contrast to the above, in our study the dietary recommendations made by nutritionists focused on a dairy-free, low-fat, gluten-free and low-fiber diet. Once again, our results are in line with previous studies; dairy products are the most commonly excluded, in 16–34% of IBD patients,24,28,29 with the exclusion of other foods also reported.24,28,29,31 Casanova et al.24 found a higher rate of food exclusion in patients with CD, although we did not find this distinction in our study.

Of the patients who made dietary changes, 73% believed they obtained therapeutic benefits regarding their gastrointestinal symptoms. In a pilot study on the FODMAP diet,33 50% of patients achieved a reduction in their abdominal pain, bloating and diarrhoea. Zallot et al. reported that less than half of their patients benefited from the dietary advice obtained,29 while de Vries et al.21 reported a benefit in 70% of the patients in terms of dietary advice. Undoubtedly, the characteristics of the populations studied (proportion of patients with inflammatory activity, degree of inflammation, proportion of patients with factors associated with bacterial overgrowth, for example strictures, absence of ileocaecal valve, gastrectomy or intestinal bypass or malabsorption of bile salts) may explain the heterogeneity of the results obtained in the different studies and even the effects of certain diets. The high rate of positive perception of dietary changes in our study may explain why they were followed for at least one year in 53% of patients and more than two years in 35%. Surprisingly, 61% excluded some food and 57% did so permanently. This was more common in females, with female patients having previously been found to have a greater tendency to eliminate food from the diet and to value nutrition as an additional treatment.21 An Italian study published in 2019 showed that 70% of patients eliminated at least one food from their diet on their own initiative.34 These data suggest that IBD patients eliminate foods believed to be related to intestinal symptoms more often than following a strict diet.

The exclusion of food permanently can involve certain risks. We know that IBD patients are already at greater risk of suffering from nutritional deficiencies such as calcium, vitamin D, iron and folic acid, due to chronic inflammation itself and the drugs used to treat it.1 If added to that, they exclude dairy products for example, they eliminate a main source of calcium, which can lead to a further decrease in bone mineralisation. Similarly, eating a low-fiber diet could be detrimental, as fiber is anticarcinogenic.35,36

In conclusion, our study found a high degree of interest in information and dietary advice in IBD, with a moderately adequate rating of the information generally received in the clinic, and a high proportion of patients seeking outside advice and excluding food or following unproven and inappropriate exclusion diets. Accurate information and health education may prevent adoption of unproven exclusion diets. It is therefore important to consider diet as an important aspect in improving patients' quality of life.

Conflicts of interestCGV: I have received financial support for educational activities from Janssen.

JGA: has received financial support for educational activities from Pfizer, Dr. Falk Pharma and Janssen.

FB: has received financial support for educational activities and travel from Abbvie, Dr. Falk Pharma, Ferring, Janssen, Kern Pharma, MSD, Norgine, Pfizer, Takeda and Tillotts Pharma, and for acting as a speaker from Pfizer.

CGM: ha received financial support for educational activities from Abbvie, MSD, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Norgine and Kern Pharma.

ALB: has not received financial support for educational activities.

EGP: has received financial support for educational activities from MSD, Abbvie, Kern, Gebro, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Faes, Tillotts Pharma and Pfizer.