The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the performance of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the diagnosis of bowel inflammation and disease activity in Crohn's disease (CD).

MethodsMEDLINE, Embase and Web of Science databases of biomedical literature were systematically searched to identify studies that investigated the diagnostic accuracy of MRI in diagnosing bowel inflammation and disease activity in CD by comparing it with reference standards. Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 tool was used to assess study quality. The summary sensitivity and specificity were estimated using the bivariate model, and hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) parameters were calculated and plotted.

ResultsOf 5492 citations of interest, 34 articles contained the diagnostic accuracy data. Of these, results for the small bowel and the colorectum were reported separately in 19 studies and jointly by 21 studies. The meta-analytic summary sensitivity and specificity under the bivariate model were 90.9% (95% CI, 85.8%–94.2%) and 90.2% (95% CI, 81.9%–95.0%), respectively. The sensitivities and specificities of individual studies ranged from 55% to 100% and 51% to 100%, respectively. Substantial heterogeneity was observed in both sensitivity (I2=84.9%) and specificity (I2=78.8%). The HSROC curve also showed considerable heterogeneity between studies.

ConclusionAlthough the meta-analytic summary accuracy of MRI was high for the diagnosis of bowel inflammation in CD, the summary estimates might be unreliable due to the presence of high heterogeneity.

El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática y metaanálisis fue determinar el rendimiento de la resonancia magnética nuclear (RM) en el diagnóstico de la inflamación intestinal y la actividad de la enfermedad en la enfermedad de Crohn (EC).

MétodosSe realizaron búsquedas sistemáticas en las bases de datos de literatura biomédica de MEDLINE, Embase y Web of Science para identificar estudios que investigaran la precisión diagnóstica de la RM en el diagnóstico de la inflamación intestinal y la actividad de la enfermedad en la EC comparándola con estándares de referencia. Evaluación de la calidad de los estudios de precisión diagnóstica: se utilizó la herramienta 2 para evaluar la calidad del estudio. La sensibilidad y la especificidad resumidas se estimaron mediante el modelo bivariado, y se calcularon y trazaron los parámetros de características operativas del receptor resumidas jerárquicas (HSROC).

ResultadosDe 5.492 citas de interés, 34 artículos contenían datos de precisión diagnóstica. De estos, los resultados para el intestino delgado y el colorrectal se informaron por separado en 19 estudios y en forma conjunta en 21 estudios. La sensibilidad y la especificidad del resumen metanalítico bajo el modelo bivariado fueron del 90,9% (IC del 95%, 85,8%-94,2%) y el 90,2% (IC del 95%, 81,9%-95,0%), respectivamente. Las sensibilidades y especificidades de los estudios individuales variaron del 55 al 100% y del 51 al 100%, respectivamente. Se observó heterogeneidad sustancial tanto en la sensibilidad (I2=84,9%) como en la especificidad (I2=78,8%). La curva HSROC también mostró una considerable heterogeneidad entre los estudios.

ConclusiónAunque la precisión del resumen metaanalítico de la RM fue alta para el diagnóstico de inflamación intestinal en la EC, las estimaciones del resumen pueden no ser confiables debido a la presencia de una gran heterogeneidad.

Crohn's disease (CD) is a type of inflammatory bowel disease that frequently affects the gastrointestinal tract including the small and large bowels.1–3 As symptoms of comorbid irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can indicate active disease, it is essential to determine the presence of inflammation prior to commencement of medical or surgical therapy even if CD is in remission.1 Additionally, it is critical to differentiate between mild, moderate or severe disease as treatments are different for various stages of the disease.1,4

Endoscopy is the reference standard for the diagnosis and staging of CD.2 However, some of its drawbacks include low patient acceptance rates and visualization of only a portion of the bowel.5 Although computed tomography (CT) is more accurate, patients are subjected to large doses of radiation.6 Because it is often necessary to frequently assess disease activity and progression of CD, repeated exposure to radiation can increase the risk of cancer incidence. In fact, in the United States of America, approximately 2% of all cancers have been associated with radiation from CT scans.7

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive technique that does not involve ionizing radiation. Hence, it is increasingly used to diagnose and stage CD.5 Whereas some studies have reported MRI to be accurate in both diagnosing and staging CD, others have suggested that MRI is either inferior to colonoscopy or has high rates of false-negatives.8–13 This necessitates a systematic review of studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of MRI in CD diagnosis and monitoring.

The aim of the present study was to conduct a systematic review of all relevant studies and to perform a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy indices to determine the performance of MRI in the diagnosis of bowel inflammation in patients with CD.

Materials and methodsSearch strategySystematic searches using a combination of search terms including “magnetic resonance imaging”, “magnetic resonance enterography”, “magnetic resonance enteroclysis”, “magnetic resonance enterocolonography”, “magnetic resonance colonography”, “Crohn's Disease” and “inflammatory bowel disease” were conducted in the Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, and Web of Science databases of biomedical literature to identify studies relevant to this review.

Initially, titles and/or abstracts were screened, and then full-text articles of potential studies were retrieved to determine eligibility. Only full-text articles and studies published in English were considered for inclusion. Case reports, narrative and systematic reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, letters, commentaries and conference abstracts or proceedings were excluded. Studies with limited data such as those lacking comparative designs, sensitivity and specificity values, or reference test procedures were also excluded. References lists of all relevant studies and systematic reviews on this topic were hand-searched to identify additional potential studies for inclusion in this meta-analysis.

Study selectionAll identified studies were carefully checked to determine if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) provided data on disease activity of CD; (2) used MRI, magnetic resonance enterography, magnetic resonance enteroclysis, or magnetic resonance enterocolonography to diagnose inflammation associated with CD; (3) used histopathology, endoscopy, colonoscopy, radiological methods, or surgery as the reference standard.

Study characteristicsThe study characteristics of all included studies were assessed, and relevant data were extracted. Data on study outcomes including true positive, true negative, false positive and false negative rates and the sensitivity and specificity values in the dichotomous diagnosis of bowel inflammation were extracted. For the study design, both observational studies (retrospective or prospective) and randomized controlled trials were considered.

Patient characteristicsThe patient characteristics that were extracted included (1) number of patients in each diagnostic arm (sample size); (2) sex distribution (number of male and female patients); (3) mean age of patients in years (range/variance); (4) part of the gastrointestinal tract examined.

Study quality assessmentThe Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool was used to determine the fulfillment of following criteria14,15:

- (1)

Representativeness of the patient population who are likely to receive MRI in real-world clinical practice.

- (2)

Clear description of patient selection criteria.

- (3)

Time between MRI and reference standard (if the time was short enough to ensure that the disease condition did not alter between the tests).

- (4)

Whether all patients in the study received the reference standard.

- (5)

Whether the entire MRI procedure was described in adequate detail to allow replication.

- (6)

Whether there was a description of the reference standard procedure in adequate detail, especially to diagnose the various stages of the disease, to allow replication.

- (7)

Whether the MRI and reference standard procedure results were evaluated and interpreted independently.

For MRI, data on (1) magnetic field strength; (2) coil used; (3) bowel preparation and type (bowel cleansing, fasting or diet status, use of spasmolytics); (4) amount and type of intravenous and/or luminal contrast medium (enteroclysis, oral and/or rectal contrast medium); and (5) bowel sequences used for disease evaluation, were identified and extracted.

Imaging criteria for staging disease activityThe imaging criteria, including pathological bowel wall thickening, bowel wall enhancement and stenosis that were used to stage CD on MRI were identified and extracted.

Data synthesis and statistical analysisAccuracy of MRI in diagnosing active bowel inflammationDescriptive analysis: The small bowel and colorectum results from all studies were analyzed separately to investigate the effect of bowel location (small versus large bowels) on the accuracy of MRI. The sensitivity and specificity values of MRI and comparator groups in each study and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were recorded. The generic inverse variance method was used to weight individual study effect sizes. Higgins I2 statistics was used to determine the presence of statistical heterogeneity across studies in summary sensitivity and specificity. Substantial heterogeneity was indicated by I2>50%. A fixed effects model was used for all outcomes where I2 was <50%, which was indicative of low heterogeneity across studies, and a random effects model was used where I2 was >50%. When the fixed-effects model was used, results were re-examined through random effects analysis, as tests of heterogeneity do not definitely exclude variation between studies.16

Meta-analytic summary: The meta-analytic summary was calculated using the hierarchical modeling methods. The bivariate random-effects model was used to obtain the summary sensitivity and specificity and their 95% CIs.17 The hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) model was used to obtain the summary receiver operating characteristic curve.18

Review Manager software (version 5.4; Cochrane Collaboration; Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen) was used to summarize article characteristics and to assess the quality of included studies with QUADAS-2 scale. For all other statistical analyses, OpenMeta[Analyst] software (Center for Evidence Synthesis in Health, Brown University, Rhode Island, USA) was used. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsInitially, 5492 citations of interest were obtained in the electronic searches from which duplicate and non-relevant citations were excluded (Fig. 1). Among the retrieved articles, 40 presented extractable data that were relevant to this meta-analysis. The diagnostic accuracy of MRI was reported by 34 articles. Of these, results for the small bowel and the colorectum were reported separately in 19 and jointly in 21 articles.

Quality assessment of studies using QUADAS-2The characteristics of all studies included in this meta-analysis are summarized in Table 1. All studies reported results on a per-bowel segment basis and were single-reader studies. Fig. 2 summarizes the quality of each study included in this meta-analysis. The main concern in these studies was the lack of blinding or no mention of blinding.

Characteristics of the articles included.

| Author | Study design | Study type | Indication for MRE/MRI | Patient age (yr) | Bowel location (sample size) | Preparation and spasmolytics | MR magnet (T) | Overall examination quality | Blinding during MRI/MRE interpretation | Reference standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adamek et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 18–68 | Mixed small and large bowels, 104 | 2000ml oral mannitol and buscopan | 3.0 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Endoscopy, surgical pathology |

| Aloi et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 12.2±4.6 | Small bowel, 34 | 250ml oral PEG and macrogol | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Consensus reference standard, ileocolonoscopy |

| Barber et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 5–15 | Mixed small and large bowels, 15 | Senna and sodium picosulphate combination | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Endoscopy |

| Beall et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 22–84 | Mixed bowels, 44 | No antiperistaltic, contrast agents | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | No | Helical computed tomography |

| Borthne et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 5–16 | Mixed small and large bowels, 43 | 1000ml oral mannitol and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Endoscopy |

| Buisson et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 12–63 | Small bowel, 31 | 1000ml oral PEG and glucagon | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | No | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE |

| Caruso et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 34–45 | Small bowel, 55 | 1500ml oral PEG and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | No | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE and endoscopy |

| Crook et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 25–83 | Small bowel, 19 | 1000ml oral mannitol and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Video capsule endoscopy |

| Darbari et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 13.2±3.8 | Mixed small and large bowels, 58 | Unstated | Unstated | Diagnostic in all patients | No | Endoscopy, surgical pathology |

| Fiorino et al. | Prospective | RCT | Usual clinical indications | 19–61 | Mixed small and large bowels, 44 | 700ml oral PEG and glucagon | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Ileocolonoscopy |

| Gale et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 4–18 | Mixed small and large bowels, 84 | 450–1350ml oral PEG and iopamidol | 1.5 or 3 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Surgical pathology |

| Gourtsoyiannis et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 18–57 | Small bowel, 52 | 1500–2000ml oral PEG and glucagon | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Enteroclysis |

| Grand et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 20–94 | Mixed small and large bowels, 310 | 900cc low-density oral contrast medium | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Endoscopy |

| Hahnemann et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 15.3–72.5 | Small bowel, 30 | 1000–1500ml oral mannitol and scopolamine | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Capsule endoscopy and ileocolonoscopy |

| Hordonneau et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 13–70 | Small bowel, 352; large bowel, 496 | 1000ml oral PEG and glucagon | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | No | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE |

| Hijaz et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 13.48±2.02 | Small bowel, 45 | 480–960ml oral PEG | Unstated | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Surgical pathology |

| Jensen et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 18–76 | Small bowel, 50 | 1000ml oral mannitol and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Ileoscopy |

| Jesuratnam-Nielsen et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 26–76 | Mixed small and large bowels, 20 | 1350ml oral barium sulphate and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Enteroclysis |

| Kim et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 18–42 | Mixed small and large bowels, 50 | 1500ml 2.5% oral sorbitol and buscopan | 3.0 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Endoscopy |

| Lai et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 1–16 | Small bowel, 55 | 2.5% oral isotonic mannitol and anisodamine | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Video capsule endoscopy and conventional gastrointestinal radiography |

| Malgras et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 18–69 | Mixed small and large bowels, 52 | 1600ml water and glucagon | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Surgical pathology |

| Miao et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 17–78 | Mixed small and large bowels, 30 | 600ml water and glucagon | 1.0 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Endoscopy |

| Neubauer et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 10–20 | Small bowel, 66; large bowel, 66 | 200–2000ml oral 2.5% mannitol and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | No | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE and endoscopy |

| Negaard et al. | Prospective | RCT | Usual clinical indications | 18–73 | Small bowel, 40 | 1000ml oral 6% mannitol and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Ileoscopy, capsule endoscopy, surgical pathology |

| Oliva et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 8–18 | Mixed small and large bowels, 40 | 2000ml oral PEG and domperidone | Unstated | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Ileocolonoscopy |

| Oto et al.1 | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 21–74 | Large bowel, 45 | 1350ml oral VoLumen and glucagon | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Endoscopy and surgical pathology |

| Oto et al.2 | Retrospective | Case-control | Usual clinical indications | 20–53 | Small bowel, 36 | 1350ml oral VoLumen and glucagon | 1.5 | Unstated | Unstated | Endoscopy and surgical pathology |

| Potthast et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 14–74 | Small bowel, 46 | 1200ml water and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Enteroclysis |

| Qi et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 13–63 | Small bowel, 100 | 1000ml oral PEG and buscopan | 3.0 | Unstated | Yes | Endoscopy |

| Rieber et al. | Retrospective | RCT | Usual clinical indications | 19–81 | Small bowel, 84 | 1000ml oral barium sulfate and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Enteroclysis |

| Sato et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Unspecified | 18–67 | Mixed small and large bowels, 141 | 1000–1500ml oral PEG and buscopan | 1.5 | Unstated | Unstated | Endoscopy |

| Schmidt et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 19–66 | Mixed small and large bowels, 48 | 2000ml oral barium sulfate and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Enteroclysis |

| Schreyer et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 18–65 | Mixed small and large bowels, 30 | 1000ml oral mannitol and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Conventional colonoscopy |

| Seastedt et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 18–78 | Mixed small and large bowels, 76 | 1350ml oral barium sulfate and glucagon | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Enterography |

| Sinha et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 19–81 | Mixed small and large bowels, 49 | 1200–1300ml oral mannitol and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Enterography |

| Taylor et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 16–45 | Small bowel, 284 | 3350ml oral mannitol or PEG | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Endoscopy |

| Van Weyenberg et al. | Retrospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 4–83 | Mixed small and large bowels, 77 | 2000ml 0.5% oral methyl-cellulose | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Capsule endoscopy |

| Wiarda et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 20–74 | Small bowel, 38 | 1000–3000ml 0.5% methyl-cellulose and buscopan | Unstated | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Balloon-assisted enteroscopy |

| Yüksel et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 26–61 | Mixed small and large bowels, 25 | 1500–2000ml 3% oral mannitol and buscopan | 1.5 | Diagnostic in all patients | Yes | Endoscopy |

| Ziech et al. | Prospective | Cohort | Usual clinical indications | 10–17 | Mixed small and large bowels, 28 | 400ml 3.5% oral sorbitol and buscopan | 3.0 | Diagnostic in all patients | Unstated | Endoscopy and surgical pathology |

MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Results of quality assessments, risk of bias and applicability concerns of the articles according to QUADAS-2 criteria. The methodological quality of all included articles is presented as the proportion of articles (0%–100%) with low (i.e., high quality), high, or unclear risks of bias and the proportion of articles with low (i.e., high quality), high, or unclear concerns regarding applicability for each domain. For articles analyzed in this study, regarding flow and timing, 64%, 16%, and 20% had low, high, and unclear risks of bias, respectively.

Results of 38 studies were published in 34 articles (17, 5, and 16 for the small bowel, colorectum, and mixed location, respectively) that provided 2488 bowel segments for the meta-analysis. Table 2 summarizes the results of meta-analysis. The sensitivities and specificities of individual studies in diagnosing active bowel inflammation with MRI ranged from 55% to 100% and 51% to 100%, respectively. Substantial statistical heterogeneity was observed in meta-analysis outcomes for both sensitivity (I2=84.9%) and specificity (I2=78.8%). The coupled forest plots of sensitivity and specificity did not show a threshold effect (Fig. 3).

Accuracy of MRI in diagnosing active bowel inflammation.

| Author | Bowel location | Reference standard | Number of bowel segments | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | FN | TN | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||

| Adamek et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy, surgical pathology | 27 | 3 | 14 | 38 | 65.9 | 76 |

| Aloi et al. | Small | Consensus reference standard, ileocolonoscopy | – | – | – | – | 88 (71, 97) | 89 (78, 96) |

| Barber et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy | 18 | 6 | 12 | 54 | 60 (40.6, 77.3) | 90 (79.5, 96.2) |

| Beall et al. | Mixed | Helical computed tomography | 19 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 95 | 100 |

| Borthne et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy | – | – | – | – | 81.8 (52.0, 94.8) | 100 (70.1, 100) |

| Buisson et al. | Small | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE | 17 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 100 (80, 100) | 93 (66, 100) |

| Caruso et al. | Small | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE and endoscopy | 31 | 4 | 0 | 20 | 100 (89, 100) | 83 (63, 95) |

| Crook et al. | Small | Video capsule endoscopy | 10 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 71.4 | 60 |

| Darbari et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy, surgical pathology | – | – | – | – | 96.4 (81.7, 99.9) | 92.3 (64.0, 99.8) |

| Fiorino et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | – | – | – | – | 88 (78, 99) | 88 (68, 100) |

| Grand et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy | – | – | – | – | 85 | 85 |

| Hahnemann et al. | Small | Capsule endoscopy and ileocolonoscopy | – | – | – | – | 55.2 | 99.5 |

| Hordonneau et al. | Small | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE | 102 | 5 | 9 | 236 | 92 (85, 96) | 98 (95, 99) |

| Hordonneau et al. | Large | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE | 62 | 4 | 2 | 428 | 97 (89, 100) | 99 (98, 100) |

| Hijaz et al. | Small Surgical pathology | – | – | – | – | 100 (55, 100) | 57.1 (28.9, 82.3) | |

| Jensen et al. | Small | Ileoscopy | – | – | – | – | 74 (57, 88) | 80 (44, 98) |

| Jesuratnam-Nielsen et al. | Mixed | Enteroclysis | – | – | – | – | 75 (23, 99) | 93 (91, 93) |

| Kim et al. | Small | Endoscopy | 25 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 81 (63, 93) | 70 (35, 93) |

| Kim et al. | Large | Endoscopy | 24 | 29 | 3 | 30 | 89 (71, 98) | 51 (37, 64) |

| Lai et al. | Small | VCE and conventional gastrointestinal radiography | – | – | – | – | 85.7 | 70 |

| Malgras et al. | Mixed | Surgical pathology | – | – | – | – | 100 | – |

| Miao et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy | 20 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 87 | 71 |

| Neubauer et al. | Small | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE and endoscopy | 26 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 100 (87, 100) | 100 (91, 100) |

| Neubauer et al. | Large | Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRE and endoscopy | 32 | 2 | 1 | 31 | 97 (84, 100) | 94 (80, 99) |

| Oliva et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | – | – | – | – | 85 (70, 94) | 89 (74, 96) |

| Oto et al.1 | Large | Endoscopy and surgical pathology | 15 | 6 | 1 | 23 | 94 (70, 100) | 79 (60, 92) |

| Oto et al.2 | Small | Endoscopy and surgical pathology | 17 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 94 (73, 100) | 89 (65, 99) |

| Potthast et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | 40 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 100 | 80 |

| Qi et al. | Small | Endoscopy | 42 | 14 | 20 | 24 | 68 (55, 79) | 63 (46, 78) |

| Rieber et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | – | – | – | – | 95.2 | 92.6 |

| Sato et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy | 17 | 22 | 4 | 98 | 81 (58, 95) | 82 (74, 88) |

| Schreyer et al. | Mixed | Conventional colonoscopy | – | – | – | – | 55.1 | 98.2 |

| Taylor et al. | Small | Endoscopy | 210 | 5 | 23 | 46 | 97 (91, 99) | 96 (86, 99) |

| Taylor et al. | Large | Endoscopy | 76 | 17 | 53 | 138 | 64 (50, 75) | 96 (90, 98) |

| Van Weyenberg et al. | Mixed | Capsule endoscopy | 31 | 1 | 8 | 37 | 79 (63, 90) | 97 (85, 100) |

| Wiarda et al. | Small | Balloon-assisted enteroscopy | 14 | 2 | 5 | 17 | 73 | 90 |

| Yüksel et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy | – | – | – | – | 92 | – |

| Ziech et al. | Mixed | Endoscopy and surgical pathology | – | – | – | – | 57 | 100 |

CI, confidence interval; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TN, true negative; TP, true positive; VCE, video capsule endoscopy.

The meta-analytic summary sensitivity and specificity under the bivariate model were 90.9% (95% CI, 85.8–94.2) and 90.2% (95% CI, 81.9–95.0), respectively. The HSROC curve also showed considerable heterogeneity between studies (Fig. 4).

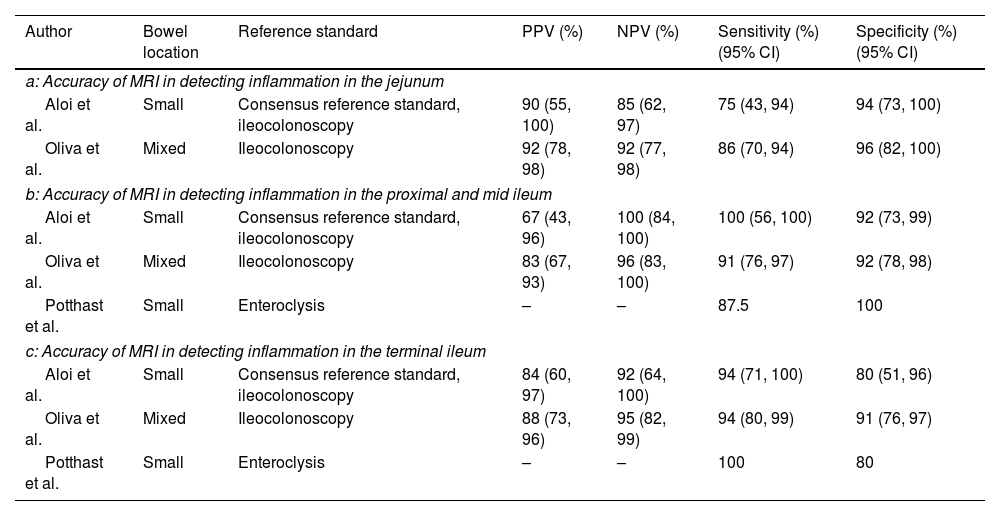

Accuracy of MRI in detecting active bowel inflammation in individual segmentsOnly 2 studies reported the accuracy of MRI in detecting inflammation in the jejunum (Table 3a).19,20 In these studies, the sensitivities were 75% (95% CI, 43–94) and 86% (95% CI, 70–94), respectively, whereas the specificities were 94% (95% CI, 73–100) and 96% (95% CI, 82–100).19,20 The reference standard in both studies were ileocolonoscopy.19,20

Accuracy of MRI in detecting inflammation.

| Author | Bowel location | Reference standard | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Sensitivity (%)(95% CI) | Specificity (%)(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a: Accuracy of MRI in detecting inflammation in the jejunum | ||||||

| Aloi et al. | Small | Consensus reference standard, ileocolonoscopy | 90 (55, 100) | 85 (62, 97) | 75 (43, 94) | 94 (73, 100) |

| Oliva et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | 92 (78, 98) | 92 (77, 98) | 86 (70, 94) | 96 (82, 100) |

| b: Accuracy of MRI in detecting inflammation in the proximal and mid ileum | ||||||

| Aloi et al. | Small | Consensus reference standard, ileocolonoscopy | 67 (43, 96) | 100 (84, 100) | 100 (56, 100) | 92 (73, 99) |

| Oliva et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | 83 (67, 93) | 96 (83, 100) | 91 (76, 97) | 92 (78, 98) |

| Potthast et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | – | – | 87.5 | 100 |

| c: Accuracy of MRI in detecting inflammation in the terminal ileum | ||||||

| Aloi et al. | Small | Consensus reference standard, ileocolonoscopy | 84 (60, 97) | 92 (64, 100) | 94 (71, 100) | 80 (51, 96) |

| Oliva et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | 88 (73, 96) | 95 (82, 99) | 94 (80, 99) | 91 (76, 97) |

| Potthast et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | – | – | 100 | 80 |

CI, confidence interval; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

The accuracy of MRI in detecting inflammation in the proximal and middle ileum was reported by 3 studies (Table 3b).19–21 All three studies reported high sensitivities and specificities ranging from 87.5% to 100% and 92% to 100%, respectively. The reference standard was ileocolonoscopy in two studies and enteroclysis in one study.19–21

Three studies assessed the accuracy of MRI in detecting inflammation in the terminal ileum and reported high sensitivities and specificities ranging from 94% to 100% and 80% to 91%, respectively (Table 3c).19–21

Accuracy of MRI in detecting other aspects of Crohn's diseaseThe accuracy of MRI in detecting bowel wall thickening was reported by 5 studies (Table 4a).22–26 Reference standards used were ileocolonoscopy, surgical pathology, enteroclysis, enterography and capsule endoscopy. The sensitivities ranged from 62.5% to 90% and specificities from 86% to 100%.22–26

Accuracy of MRI in detecting symptoms in Crohn's disease.

| Author | Bowel location | Reference standard | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Sensitivity (%)(95% CI) | Specificity (%)(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a: Accuracy of MRI in detecting bowel wall thickening in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Fiorino et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | – | – | 90 (86, 100) | 91 (76, 100) |

| Gale et al. | Mixed | Surgical pathology | – | – | 69 (64, 74) | 91 (87, 94) |

| Gourtsoyiannis et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | 100 | 84.6 | 62.5 | 100.0 |

| Negaard et al. | Small | Ileoscopy, capsule endoscopy, surgical pathology | 89 | 89 | 88 | 89 |

| Sinha et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 90 | 72 | 79 (62, 91) | 86 (68, 96) |

| b: Accuracy of MRI in detecting bowel wall enhancement in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Fiorino et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | – | – | 81 (65, 97) | 95 (86, 100) |

| Gale et al. | Mixed | Surgical pathology | – | – | 53 (47, 59) | 96 (93, 98) |

| Negaard et al. | Small | Ileoscopy, capsule endoscopy, surgical pathology | 93 | 94 | 93 | 94 |

| Sinha et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 50 | 91 | 89 (69, 98) | 53 (42, 57) |

| c: Accuracy of MRI in detecting fistulas in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Fiorino et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | – | – | 40 (0, 82) | 94 (87, 100) |

| Gourtsoyiannis et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | 75 | 100 | 100 | 97.8 |

| Potthast et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | – | – | 87 | 93 |

| Rieber et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | – | – | 70.6 | – |

| Schmidt et al. | Mixed | Enteroclysis | – | – | 44.4 | 100 |

| Seastedt et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 100 | 81 | 60 | 100 |

| Sinha et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 100 | 95 | 76 (61, 77) | 99 (95, 99) |

| d: Accuracy of MRI in Detecting Strictures in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Fiorino et al. | Mixed | Ileocolonoscopy | – | – | 92 (79, 100) | 90 (79, 100) |

| Sinha et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 100 | 88 | 56 (41, 63) | 98 (93, 99) |

| e: Accuracy of MRI in detecting superficial ulcers in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Gourtsoyiannis et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | 40 | 92.3 | 57.1 | 85.7 |

| Sinha et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 89 | 84 | 50 (38, 55) | 97 (93, 99) |

| f: Accuracy of MRI in detecting deep ulcers in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Gourtsoyiannis et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | 100 | 93.8 | 89.5 | 100 |

| Sinha et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 96 | 90 | 69 (56, 71) | 98 (92, 99) |

| g: Accuracy of MRI in detecting stenosis in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Gourtsoyiannis et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | 91.3 | 100 | 100 | 92.9 |

| Negaard et al. | Small | Ileoscopy, capsule endoscopy, surgical pathology | 75 | 96 | 86 | 93 |

| Potthast et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | – | – | 100 | 96 |

| Schmidt et al. | Mixed | Enteroclysis | – | – | 44.4 | 100 |

| Seastedt et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 100 | 65 | 68 | 100 |

| h: Accuracy of MRI in detecting abscess in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Potthast et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | – | – | 100 | 97 |

| Rieber et al. | Small | Enteroclysis | – | – | 77.8 | – |

| Schmidt et al. | Mixed | Enteroclysis | – | – | 83.3 | 100 |

| Seastedt et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 87 | 97 | 87 | 87 |

| Sinha et al. | Mixed | Enterography | 100 | 98 | 77 (48, 79) | 100 (97, 100) |

CI, confidence interval; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Four studies (Table 4b) reported the accuracy of MRI in detecting bowel wall enhancement. The sensitivities ranged from 53% to 93% and specificities from 53% to 96%.22,23,25,26

The accuracy of MRI in detecting fistulas was reported by 7 studies (Table 4c).21,22,24,26–29 Enteroclysis, enterography and ileocolonoscopy were the reference standards used. The sensitivities ranged from 40% to 100% and specificities from 93% to 100%.21,22,24,26–29

Two studies reported the accuracy of MRI in detecting strictures (Table 4d).22,26 Ileocolonoscopy and enterography were the reference standards used. Whereas the sensitivity and specificity in one study were 92% and 90%, respectively22; the other reported the sensitivity and specificity of 56% and 98%, respectively.26

The accuracy of MRI in detecting superficial and deep ulcers was reported by two studies (Table 4e and f).24,26 Enteroclysis and enterography were the reference standards used. In one study, the sensitivity and specificity of detecting superficial ulcers were 57.1% and 85.7%, respectively, whereas the sensitivity and specificity of detecting deep ulcers were 89.5% and 100%, respectively.24,26 In the other study, the sensitivity and specificity of detecting superficial ulcers were 50% and 97%, respectively, whereas the sensitivity and specificity of detecting deep ulcers were 69% and 98%, respectively.26

Five studies reported the accuracy of MRI in detecting stenosis (Table 4g). Enteroclysis, enterography, ileoscopy, capsule endoscopy and surgical pathology were the reference standards used. The sensitivities ranged from 44.4% to 100% and specificities from 92.9% to 100%.21,24,25,28,29

The accuracy of MRI in detecting abscess was reported by five studies (Table 4h). Enteroclysis and enterography were the reference standards used. The sensitivities ranged from 77% to 100% and the specificities from 87% to 100%.21,26–29

DiscussionThis systematic review and meta-analysis has demonstrated that MRI has high accuracy in diagnosing active bowel inflammation with the meta-analytic summary sensitivity and specificity of 90.9% (95% CI, 85.8%–94.2%) and 90.2% (95% CI, 81.9%–95.0%), respectively. However, there was high statistical heterogeneity between studies as indicated by I2 of 85% for sensitivity and I2 of 79% for specificity. Hence, these meta-analytical summary estimates do not achieve sufficient degree of reliability.

Consistent with the high statistical heterogeneity in the results of this meta-analysis, the diagnostic accuracies for bowel inflammation of CD reported in individual studies were also highly heterogeneous, as sensitivity and specificity values ranged from 55% to 100% and 51% to 100%, respectively. Thirty three percent of the included studies reported sensitivity below 80% and 22% of the included studies reported specificity below 80%. Furthermore, not all bowel segments or conditions affecting the bowel in CD were evaluated in all studies, making it difficult to identify the accuracy of MRI for all bowel segments and all conditions.

Among the reference standards, endoscopy was the most utilized modality which was used in 51% the included studies. This was followed by the surgical pathology (18%), enteroclysis (9%), and enterography (9%). Moreover, many studies used more than one reference standards. Use of different reference standards may also be the source of heterogeneity. Bowel preparation is also an important confounder in the outcomes of endoscopies and may also affect MRI outcomes. Moreover, recently it has been found that the timing of bowel preparation may also affect the outcomes of a test or reference. All such factors can affect the outcomes of individual studies and thence bring heterogeneity in the meta-analysis. Included studies were either prospective or retrospective in design. Retrospective studies may have several types of biases inherently that can affect the outcomes of a meta-analysis combining data arising from studies with different designs.

This meta-analytical review has some limitations. Firstly, statistical heterogeneity was high in the meta-analytical summary estimates which attenuates the reliability of MRI in CD diagnosis. It was difficult to determine the causes of between-study statistical heterogeneity due to less availability of related information in the research articles of the included studies. Secondly, methodological issues might have also played a role in outcomes observed herein. For example, most studies did not specify the exact criteria to define test positivity on MRI. Moreover, the quality of the examination for individual bowel segments was also not separately reported.

ConclusionsThe meta-analytic summary accuracy of MRI was quite high for the diagnosis of bowel inflammation in CD. However, it is likely that some studies may have overestimated the accuracy of MRI, as adequate blinding was not used during interpretation of the MRI or was not reported by some studies. Hence, this could have accounted for the large between-study statistical heterogeneity observed herein. As a result, the meta-analytic summary estimates might be unreliable. Nevertheless, MRI can be used for the diagnosis of bowel inflammation in CD.

FundingThis research was supported by the Heath Commission of Heilongjiang Province (No. 2020-245).

Conflict of interestNone.

None.