Many drugs can produce enterocolitis and they should always be included in the differential diagnosis of this clinical picture. Entities such as antibiotic-associated colitis and neutropenic colitis have been known for some time and recently a new type of drug-induced colitis has emerged due to monoclonal antibodies.

Ipimumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the CTLA4 molecule that is involved in the maturation and regulation of T lymphocyte activation. This drug causes immune activation and has an immune-mediated antitumor effect with excellent results in tumours such as melanoma. However, several immune-related adverse effects may occur in different organs. The most frequently involved site is the gastrointestinal tract, with adverse effects ranging from mild diarrhoea to colitis with systemic involvement, intestinal perforation, and even death.

Although no similarities have been found in the pathogenesis with inflammatory bowel disease, treatments have been used in correlation with its autoimmunological profile: anti-TNF alpha corticosteroids have shown clinical efficacy in moderate to severe disease. However the use of anti-TNF treatment has not been defined and the safety profile is unknown. The inclusion of these new therapies in the treatment of several tumours requires familiarity with these entities and their management should be approached as a new challenge for the gastroenterologist.

For that reason, we conducted a review of ipilimumab-induced colitis, evaluating essential features of its symptoms, diagnosis and treatment.

Existen numerosos fármacos de diversas clases que pueden producir enterocolitis y deberían incluirse siempre en el diagnóstico diferencial de este cuadro clínico. Si ya conocíamos entidades como la colitis asociada a antibióticos o la colitis neutropénica asistimos en la actualidad a un nuevo cuadro de colitis inducida por inmunofármacos.

Ipimumab es un anticuerpo monoclonal humanizado que actúa contra la molécula CTLA4, que se encuentra implicada en la regulación de la maduración y activación del linfocito T. Este fármaco ocasiona una activación inmunológica y un efecto antitumoral inmunomediado con excelentes resultados en tumores como el melanoma. Sin embargo, son varios los efectos adversos de tipo inmunomediados que puede producir en distintos órganos, siendo el tubo digestivo uno de los más frecuentes, ocasionando desde una diarrea leve hasta cuadros de colitis con afectación sistémica, perforación intestinal e incluso muertes.

Aunque no se han encontrado similitudes en la patogenia con la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal dada su base inmunológica se han utilizado terapias en correlación con la misma: corticoides e incluso anti-TNF alfa han mostrado eficacia clínica en cuadros moderados y graves. Sin embargo, las pautas de tratamiento anti-TNF no se encuentran definidas ni conocemos su perfil de seguridad.

La inclusión de estas nuevas terapias en el tratamiento de diferentes tumores nos obliga a conocer estas entidades y afrontar su manejo como un nuevo reto para el gastroenterólogo.

Por este motivo, hemos querido realizar una revisión de la colitis inducida por ipilimumab tratando los aspectos esenciales en la clínica, diagnóstico y terapéutica.

Little is known about the prevalence of drug-induced colitis, and incidence is probably underestimated. Nevertheless, it should always be borne in mind and included in the differential diagnosis of enterocolitis.

IntroductionThe compounds most commonly associated with drug-induced colitis are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and antibiotics, the latter being the cause of the classic Clostridium difficile-induced colitis.1 However, other drug groups have also been associated with colitis caused by various pathogenic mechanisms, such as infection, ischaemia or immune-inflammatory processes; these include lansoprazole, ticlopidine, clozapine, vasoconstrictors, progestogens and various cytotoxic agents used in oncology, such as irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine and docetaxel, among others. Another characteristic clinical condition, neutropenic colitis or typhlitis, has also been associated with the use of these agents.2,3

Incidence of drug-induced colitis is growing following the introduction of biological therapies in oncology, where cases of diarrhoea and colitis secondary to administration of different types of drugs such as selective epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (cetuximab, panitumumab, erlotinib) and selective vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (bevacizumab), as well as antibodies against immune checkpoints, such as anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 antibodies (ipilimumab) have been reported.3,4

Ipilimumab can cause characteristic and potentially serious colitis. If the current trend towards increased use of this drug in different tumours continues, gastroenterologists will most probably become involved in the management of the disease, which has prompted us to compile this review of the symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced colitis.

What is ipilimumab and what is it used for?Ipilimumab is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4).

T-lymphocyte maturation in the lymph nodes begins with the interaction between the antigen presenting cell (APC) and the T-lymphocyte, involving presentation of the antigen bound to the major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I) antigen, which must bind to the T-cell receptor. This results in the maturation, activation and proliferation of a specific T-cell clone. This process must be tightly regulated, and requires a second co-stimulatory signal produced when T-cell surface protein CD28 binds to protein B7 on the APC. These 2 signals trigger the immune response with T-cell activation and proliferation in an antigen-specific response.

CTLA4 (CD152) is a type I membrane protein that is expressed on T-lymphocytes and monocytes, and is generally sequestered in intracellular vesicles. Once the immune response has been activated through the mechanisms described, CTLA4 is transported (as a regulatory molecule) to the cell surface of the lymphocyte and binds to proteins of the B7 family expressed on APCs, preventing CD28-B7 complex formation and dampening the amplitude of the initial response.

Ipilimumab blocks the CTLA4 protein by binding to its surface when it is expressed on the membrane. This results in permanent stimulation of the lymphocyte through suppression of inhibitory/regulatory signals. The mechanism of action described suggests that this drug will have an immune-mediated anti-tumour effect by maintaining an “unrestrained” immune system.5

The excellent results of various studies published on ipilimumab have revolutionized the systemic treatment of unresectable and metastatic melanoma, which is associated with poor survival when treated with other drugs. Ipilimumab has shown a benefit in overall survival in various clinical trials, with 3-year survival rates of 22%, and it is currently indicated in first- and second-line treatment of metastatic melanoma.5–11

Why can it cause colitis?The mechanism of action of this monoclonal antibody facilitates the appearance of autoimmune-type side effects derived from the production of autoreactive T-lymphocytes against different tissues. These effects were demonstrated in an animal model by Tivol et al., 13 who genetically modified mice, blocking the gene that codes for CTLA4. They observed lymphocytic hyperproliferation, diffuse lymphadenopathies, and lymphocyte infiltration in tissues such as the myocardium.13 Today, these “immune-mediated” or “immune-related” adverse effects are well characterized in humans, their chronology has been documented, and algorithms have been developed for their management.5,11

These adverse effects are of major clinical importance due to their high incidence (over 70% of cases) and potentially serious nature (in up to 25% of cases). The organs most affected are, in order of frequency, the skin (47%–68%), digestive tract (31%–46%), liver (3%–9%) and pituitary gland (4%–6%). Involvement of other organs such as the pancreas, uvea, etc. has also been described.

The most common manifestation in respect to intestinal involvement is diarrhoea, which usually onsets between 6 and 16 weeks after commencing therapy.14 Depending on the form of presentation, it can be a mild, self-limiting process, or have serious clinical symptoms of colitis with large gastrointestinal losses, abdominal pain, bloody stools, need for intravenous fluid-electrolyte replacement, systemic involvement, etc. This has been described in 18% of cases, and in early drug trials led to 1% of toxic deaths secondary to intestinal perforations.6,10–12,14–16 The descending colon is generally most affected, although the entire colon may be involved. Colonoscopy shows variable mucosal involvement, which is generally diffuse and ranges from erythema and oedema, with or without friability, to deep ulcers with spontaneous bleeding in the most serious cases. Biopsy can reveal a neutrophilic or non-specific mixed infiltrate.8,17,18

Is it Crohn-type or ulcerative-type inflammatory colitis?Cases of Crohn disease associated with the use of biological agents such as rituximab or etanercept have been described.19–23 The pathogenesis is not very clear, and it has been postulated that the use of these drugs simply unmasks a hitherto silent disease.24

Berman et al.,18 in a population of 115 patients who started ipilimumab treatment, carried out a series of analyses that might explain the pathogenic differences between this process and what is so far known to occur in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). These included:

- –

The serological pattern of antibodies against bacterial flora: unlike Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, in which anti-S cerevisiae antibody (ASCA) or perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (p-ANCA) positivity is highly predictive,25 more than half the patients in this series with ASCA or p-ANCA positivity did not develop induced colitis.

- –

Similarly, production of different antibodies (ASCA, p-ANCA, outer membrane porin C [OmpC], anti-flagellin [antiCBir1], Pseudomonas fluorescens anti-I2) was much more unstable and fluctuating than that observed in Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis.26

- –

No association was found between the different polymorphisms described in 10 genes implicated in the immune response (which include CTLA4, NOD2 and IL23R) and patients who developed colitis; in contrast, these associations were found in IBD.27,28

- –

Histological changes in the mucosa: in a series of 78 patients who developed colitis after ipilimumab, 27 underwent endoscopy with biopsy; none showed the histological features of chronicity observed in Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. The most frequent findings were neutrophilic infiltration in the lamina propria.

- –

Clinical course: colitis induced by this drug is an acute process and to date no new flare-ups have been reported if administration is not resumed.

This, therefore, suggests that this drug causes acute immune-mediated inflammatory colitis that has nothing to do with chronic Crohn or ulcerative colitis-type IBD.

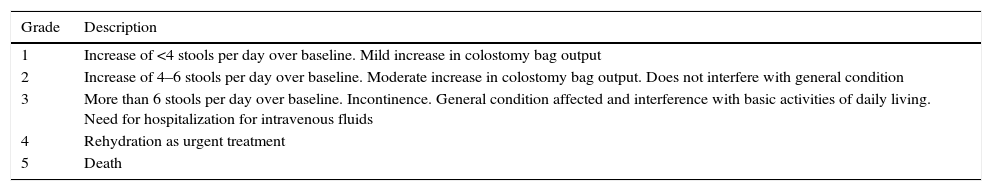

How is it treated?Before considering treatment for this entity, other causes of diarrhoea or colitis for which there is a specific treatment must be ruled out, perhaps the most important of which is infection. Once this has been ruled out, the diarrhoea-colitis secondary to ipilimumab algorithm can be applied, which considers the severity of symptoms (Table 1) and is probably similar to the therapeutic toolkit available in IBD in cases of colitis5,14:

- –

For mild cases (diarrhoea grade 1–2 according to National Cancer Institute toxicity criteria, which consists of up to 6 stools per day, without requiring intravenous fluids for more than 24hours and without interfering with the patient's general condition), an astringent diet and use of loperamide is indicated.29,30

- –

In more serious situations (grade 3–4) or in mild situations that have not responded to initial treatment, 1mg/kg oral steroids are recommended in a tapered regimen (for at least 1 month). In the case of oral intolerance, refractoriness to oral administration or systemic involvement, this treatment should be initiated intravenously.

Criteria for classification of diarrhoea severity.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Increase of <4 stools per day over baseline. Mild increase in colostomy bag output |

| 2 | Increase of 4–6 stools per day over baseline. Moderate increase in colostomy bag output. Does not interfere with general condition |

| 3 | More than 6 stools per day over baseline. Incontinence. General condition affected and interference with basic activities of daily living. Need for hospitalization for intravenous fluids |

| 4 | Rehydration as urgent treatment |

| 5 | Death |

No studies have been conducted on oral and topical mesalazine or steroid enemas, but some authors suggest that they can be used due to their good safety profile and similarity to other IBD therapies.31

For cases refractory to intravenous steroids, or in which colitis reappears after lowering the steroid dose, the currently recommended medication (except for the usual contraindications) is infliximab.32

Surgery is indicated in cases of acute abdomen/perforation, but depends on the patient's prognosis for the underlying disease.

This algorithm obviously has weak points, such as no information on the steroid dose required, mode of administration, and management when they are given for another reason (hypophysitis, etc.), but probably the weakest is the indication for infliximab and its subsequent management for various reasons.

The first drawback involves the limited experience with this treatment, as there are no established treatment regimens. Pages et al.33 reviewed various case reports and short uncontrolled case series published up to 2013, comprising 20 patients treated with infliximab for grade 2/3 colitis after receiving ipilimumab for metastatic melanoma at different doses and dosage regimens. Some of these had not received steroids as an intermediate step. Although the results are not included according to any specific criteria (and in some cases are not even reported), in most studies, infliximab was effective a few days after infusion of a 5mg/kg dose (in some cases a second dose was given due to lack of response to the first, and in others it was prescribed without reporting the response to the first). The only adverse effect was 1 case of systemic candidiasis that caused death of the patient.

The second, and no less important, limitation is the lack of information on the evolution of the tumour after infliximab treatment. Rheumatology and Gastroenterology clinical guidelines do not generally recommend the use of anti-TNF agents if there is a previous or current history of neoplasms. Instead, they leave this to the discretion of the physician, following careful assessment. These drugs can be considered once the tumour is controlled and some time has passed since diagnosis.34–36 The use of anti-TNF agents is also known to be associated with the development of melanoma-type tumours.37 This is basically due to the apoptotic effect of TNF-alpha. Studies in patients who received infliximab for ipilimumab-induced colitis are unclear on this issue. In the most extensive series,33 3 of the patients in whom outcomes were reported presented tumour progression. In any event, it would be difficult to attribute this effect exclusively to infliximab therapy, since there are no controlled series in this respect.

One peculiar feature of ipilimumab therapy is that tumour response is favourable in patients presenting immune-mediated side effects 38–40; however, these results cannot be extrapolated to patients with colitis who require infliximab, since data are scant and any association could be misleading.

Can patients continue to receive ipilimumab after an immune-mediated adverse effect?Evidence in this respect is anecdotal, although it may be said that following an episode of grade 3–4 diarrhoea/colitis, the drug should not be restarted if the usual doses have not been completed. This can be extended to other adverse effects, unless they are mild. There are some cases of mild diarrhoea in which, following temporary discontinuation of ipilimumab treatment and administration of oral steroids, treatment can be resumed without any new incidents.5,14

Nevertheless, the effects must be mild and patients must be fully informed, as drugs such as lambrolizumab/pembrolizumab and nivolumab (with immune-mediated cytotoxic activity due to blockade of the PD-1 receptor) are available, for which a therapeutic benefit similar to that of ipilimumab has been described (even in cases of where ipilimumab has failed) associated with lower digestive toxicity (1% colitis).41–43

Can ipilimumab be used in patients with melanoma and inflammatory bowel disease?Only 1 publication, a Letter to the Editor describing the use of ipilimumab in a young patient with resected Crohn disease who was asymptomatic and not on treatment, has so far addressed this issue. After administration of ipilimumab for metastatic melanoma (once confirmed that the patient had minimum endoscopic involvement at colon level), the patient presented diarrhoea with up to 5 stools daily without blood. This was treated with loperamide, since endoscopic involvement was equally mild and histological changes did not suggest that they were secondary to the underlying disease.44

Are there markers of severity and/or treatment response?No clinical, analytical or endoscopic data have been found to date that can predict the response to steroids or indication for infliximab or surgery, so their use should be based on the clinical response and the patient's general condition according to the proposed algorithm.

Can colitis be prevented?Berman et al.18 published a study on prophylaxis with 9mg of budesonide during ipilimumab treatment in a placebo-controlled series with 115 patients. Onset of diarrhoea and/or colitis did not differ in either treatment arm (36.2% vs 35.1%), so at present there is no effective therapy to prevent colitis. They did demonstrate, however, that tumour progression was similar in both arms.

In the same study, it was observed that early endoscopic changes found after receiving ipilimumab did not predict the development of grade 2–3 diarrhoea in either subgroup. Similarly, serial calprotectin levels did not identify patients who developed grade 3–4 diarrhoea either.

ConclusionsThere are a number of drugs of various classes that can cause colitis symptoms and, therefore, must always be included in the differential diagnosis of acute and chronic colitis.

Ipilimumab is already widely used in the treatment of advanced melanoma, and has shown clear benefits. Due to its mechanism of action, it is associated with immune-type adverse effects, particularly intestinal involvement, that are common and occasionally serious.

A management algorithm for the treatment of diarrhoea and colitis according to the degree of severity and response to prescribed treatments has been developed.

The evidence relating to infliximab treatment is scant, and it appears beneficial; as regards safety, short- and long-term evolution, particularly from an oncological point of view, is unknown.

Again, further studies are required to characterize the efficacy and safety of infliximab treatment. New preventive and therapeutic strategies in the management of this clinical condition are also needed, since the impressive results of their phase I trials implies that ipilimumab or other immunotherapy agents will be used increasingly to treat other tumours in the near future (lung, prostate, gastric, pancreatic, breast, urothelial and renal cancer, lymphomas, etc.).45–48 For this reason, understanding this cause of colitis and its specialized management will soon be essential for gastroenterologists and oncologists.

FundingNo funding of any type was received for this manuscript.

Conflict of interestsThe authors confirm that there is no conflict of interests in relation to the publication of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Mesonero F, López-Sanromán A, Madariaga A, Soria A. Colitis secundaria a ipilimumab: un nuevo reto para el gastroenterólogo. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:233–238.