The biosimilar of infliximab (CT-P13) has been approved for the same indications held by the infliximab reference product (Remicade®); however, there are few clinical data on switching in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy, safety, bioavailability profile and factors associated with relapse after switching to biosimilar infliximab in IBD patients in clinical remission.

Material and methodObservational study with IBD patients treated with Remicade® for at least 6 months and in clinical remission for at least 3 months who switched to infliximab biosimilar. The incidence of relapse, adverse effects and possible changes in drug bioavailability (trough level and antidrug antibodies) were evaluated.

ResultsThirty six patients were included (63.9% CD) with a mean follow-up of 8.4 months (SD±3.5). The 13.9% had clinical relapse. The longer clinical remission time before switching (HR=0.54, 95% CI=0.29–0.98, p=0.04) and detectable infliximab levels at the time of switching (HR=0.03, 95% CI=0.001–0.89, p=0.04) were associated with a lower risk of relapse. No differences were found between infliximab levels at the time of switching and at weeks 8 and 16 (p=0.94); 8.3% of the patients had some adverse event, requiring the suspension of biosimilar in one patient for severe pneumonia.

ConclusionSwitching to biosimilar infliximab in a real-life cohort of IBD patients in clinical remission did not have a significant impact on short-term clinical outcomes. The factors associated with relapse were similar to those expected in patients continuing with Remicade®.

Infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) ha sido aprobado para las mismas indicaciones que infliximab original (Remicade®); sin embargo, hay pocos datos clínicos sobre el intercambio en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII). El objetivo del estudio fue evaluar la eficacia, la seguridad, el perfil de biodisponibilidad y los factores asociados a la recidiva tras el intercambio a infliximab biosimilar en pacientes con EII en remisión clínica.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional con pacientes con EII tratados con Remicade® durante al menos 6 meses y en remisión clínica durante al menos 3 meses, a los que se realizó el intercambio a infliximab biosimilar. Se evaluó la incidencia de recidiva, los efectos adversos y los cambios en la biodisponibilidad del fármaco (niveles y anticuerpos).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 36 pacientes (63,9% EC), con una media de seguimiento de 8,4 meses (±3,5). El 13,9% presentaron recidiva clínica. El mayor tiempo de remisión clínica previo al intercambio (HR=0,54; IC 95%=0,29-0,98; p=0,04) y niveles de infliximab detectables en el momento del intercambio (HR=0,03; IC 95%=0,001-0,89; p=0,04) se asociaron a menor riesgo de recidiva. No hubo diferencias entre niveles de infliximab en el momento del intercambio y en las semanas 8 y 16 (p=0,94). El 8,3% presentaron algún efecto adverso, requiriendo suspensión del fármaco en un paciente por neumonía grave.

ConclusiónEl intercambio a infliximab biosimilar en una cohorte de vida real de pacientes con EII en remisión clínica no parece tener un impacto significativo en los resultados clínicos a corto plazo. Los factores asociados con la recidiva fueron similares a los esperados en pacientes que continúan con Remicade®.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and its two main clinicopathological manifestations, Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are characterised by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and unpredictable alternating periods of activity and remission.1 Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of both diseases and its serum levels increase in the event of activity.2 The advent of tumour necrosis factor blocking agents radically altered the prognosis of patients with IBD. Infliximab (Remicade®) was the first anti-TNF drug to be approved for clinical use and there is evidence to support its safety and efficacy to induce and maintain remission in IBD patients.3,4 Remicade® has improved the prognosis of these patients by reducing the progression of structural damage, the risk of complications and the need for surgery and hospitalisation.5 Approximately two-thirds of patients with CD initially respond to anti-TNF therapy. However, its efficacy is not maintained over time and it is estimated that 10–50% of patients with IBD who initially respond to Remicade® subsequently require a change of treatment or a dose adjustment due to lack of response. The estimated annual risk of loss of response is approximately 13% per patient-year of treatment.6,7

Biological drugs are much more expensive than conventional medicines, resulting in a considerable financial burden on public health systems given the increasing number of patients requiring treatment.1

The introduction of biosimilars has had a significant impact on maintaining the sustainability of the health system thanks to the financial savings they entail.8–11 Extremely thorough comparability testing has shown the biosimilar infliximab to be highly similar to the reference product in terms of quality, safety and efficacy.1

CT-P13 (Remsima®, Inflectra®) is an infliximab biosimilar of the reference product Remicade®, whose application in the treatment of rheumatic diseases was evaluated in the PLANETAS and PLANETRA pivotal clinical trials.12,13 These randomised studies demonstrated the equivalence of the biosimilar infliximab with its reference product in terms of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety profile in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), respectively.1 As a result, CT-P13 was the first biosimilar monoclonal antibody to be approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). After demonstrating its efficacy and safety in patients with rheumatic diseases, the European regulatory agency authorised the extrapolation of these data and approved its use in the treatment of patients with IBD. In subsequent studies, biosimilar infliximab was administered to patients with moderate-severe CD and UC, demonstrating clinical efficacy to induce and maintain remission.14–17

The concept known as switching refers to the supply of a ‘biosimilar’ drug instead of the original medicinal product. Although decisions regarding the suitability of switching to a biosimilar drug do not fall under the remit of the regulatory agencies, evidence from rheumatic diseases suggest that switching is effective and safe, with no differences in terms of immunogenicity.12,13 There is very limited experience of switching in patients with IBD. Most published studies include a small number of patients with very limited follow-up.18–20 Furthermore, pharmacokinetic and immunogenicity data are scarce, even taking into account rheumatic diseases.

The aim of this study was to assess loss of efficacy, safety and factors associated with relapse after switching from Remicade® to biosimilar infliximab in patients with IBD in clinical remission in Spain, as well as to identify any changes in bioavailability after switching.

Materials and methodsStudy design and patientsThis was an observational, retrospective and single-centre study comprising a single cohort of patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) who switched from reference infliximab (Remicade®) to biosimilar infliximab (Remsima®) between November 2015 and August 2016 at Hospital Reina Sofía in Córdoba, Spain. The information was obtained retrospectively by reviewing the patients’ electronic medical records. The dose and administration interval did not change after switching. CT-P13 (Remsima®) was administered to most patients at a dose of 5mg/kg every 8 weeks. However, five patients were on a higher dose of Remicade® prior to switching, and this higher dose was maintained after switching to biosimilar infliximab.

Patients who had received at least six months of maintenance therapy with the reference product (Remicade®) and who were in corticosteroid-free clinical remission for at least three months were enrolled. Clinical remission was defined as a score ≤4 points on the Harvey-Bradshaw index for luminal CD, the cessation of fistula drainage either spontaneously or under gentle manual compression for perianal disease, and a score <2 points on the partial Mayo score for UC.21,22 Patients under the age of 18 years and patients treated with reference infliximab for an indication other than IBD were excluded.

The study was conducted in accordance with international ethical guidelines for research and clinical studies in humans established in the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent updates, and with the recommendations of the Spanish Ministry of Health concerning clinical studies. The study protocol was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Córdoba. All patients received an information sheet and gave their written consent to participate in the study.

Baseline characteristicsDemographic and clinical data, including family history, history of smoking, type and location of IBD, CD clinical pattern, disease duration, surgical resections or perianal surgery, as well as prior history of treatment with immunosuppressants or biological drugs, including prior treatment with infliximab, were recorded from each patient's electronic medical record. Data such as biological remission, defined as CRP <5mg/l, indication for treatment with Remicade®, duration of treatment and the need to escalate Remicade® prior to switching, concomitant treatment with immunosuppressants and the duration of clinical remission prior to switching to Remsima® were also recorded.

AssessmentsRelapse or loss of responseThe primary endpoint was relapse or loss of response to treatment after switching, defined as increased activity as assessed by the clinic, as well as laboratory, radiology and endoscopy findings, which led to a change in the patient's treatment in order to control his/her disease.

Before each infusion, patients underwent an examination. The Harvey-Bradshaw index was used to assess the clinical activity of CD and the partial Mayo score to assess UC. Lab tests were also conducted and activity was assessed in the event of any sign or symptom suggestive of loss of response to treatment.

Bioavailability and immunogenicityLevels of infliximab and ATI (antibodies to infliximab) were measured in all patients before administering each infusion of Remicade® and the biosimilar CT-P13 after switching. These measurements were taken using the Promonitor®-IFX and Promonitor®-Anti-IFX (Progenika Biopharma S.A., Vizcaya, Spain) ELISAs (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays),23,24 which measure levels of both Remicade® and Remsima® as well as antibodies to both drugs, respectively.

SafetyThe safety data recorded at each infusion and during the period preceding the next dose of the drug were collected. Any harmful, unintentional or unfavourable medical event that occurred or worsened during a patient's clinical course and which was reported on the nursing record sheet or the patient's electronic medical record was described as an adverse effect. The type of adverse effect, its seriousness and if Remsima® had to be withdrawn were also reported.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® software version 20.0 (Chicago, USA). The variables were presented in frequency tables or expressed as means and standard deviation, except those variables with asymmetrical distribution, for which the median and interquartile range were used. The chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test when necessary) was used for the frequencies, Student's t test or ANOVA for the quantitative variables and the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test for asymmetrical distributions.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the impact of switching to biosimilar CT-P13 on relapse-free survival, while the log-rank test was used to compare the curves. Finally, a multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of the various prognostic factors on relapse-free survival after switching. A p<0.05 was considered significant. The larger Cox model comprised those variables with p<0.25. Clinically significant variables identified in prior studies irrespective of their significance in the univariate analysis were also included. Covariates were removed from the larger Cox model by means of a step-by-step process, eliminating those variables with a p>0.15 one by one, starting with the variables with the highest p-value. The remaining covariates formed the smaller Cox model. The variables with a p-value between 0.05 and 0.15 were selected to identify potential confounding factors and were removed from the model if they did not behave as such.

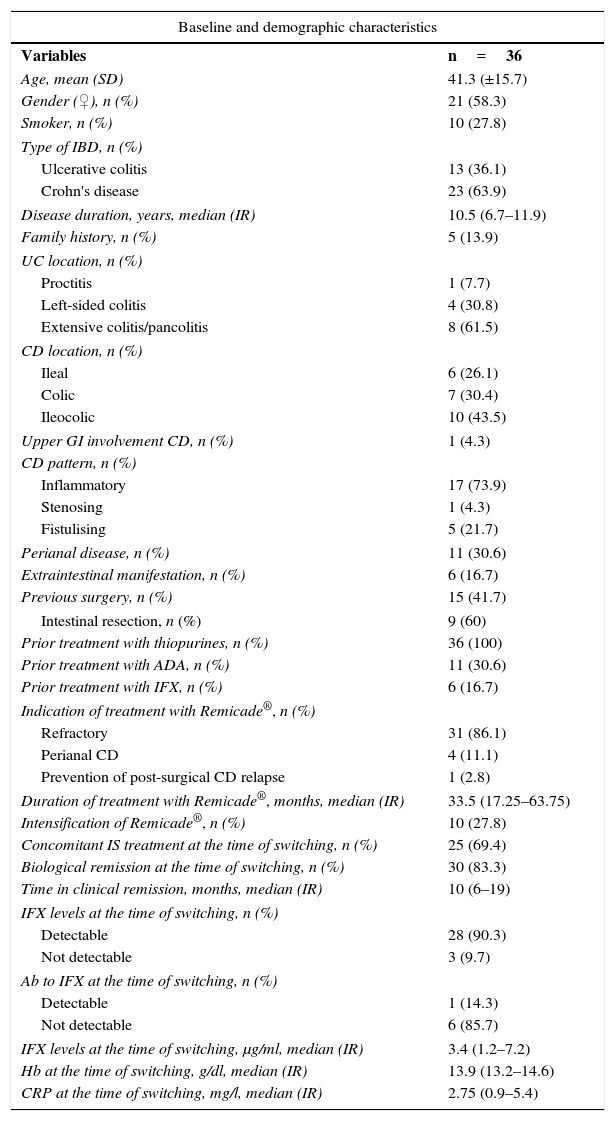

ResultsClinical and baseline characteristics of patientsIn total, 36 patients with IBD (13 with UC, 23 with CD) were included in the study. The average age of the patients was 41.3 years (±15.7) and 58.3% were women. 43.5% of CD patients had ileocolic Crohn's disease and 73.9% had an inflammatory pattern. 61.5% of UC patients had extensive colitis. Median disease duration was 10.5 years (6.7–11.9). 16.7% of patients had one or more extraintestinal manifestations. Of all the patients with CD and UC, 15 (41.7%) had undergone previous surgery (six patients required intestinal resection, six perianal surgery and three both procedures). All the patients who underwent intestinal resection had CD and were prescribed infliximab as they were refractory to immunosuppressants after post-surgical relapse. In addition, 16 patients had a prior history of exposure to treatment with an anti-TNF: nine had received adalimumab (Humira®), four Remicade®, two had used both agents and one patient had received golimumab (Simponi®). The most common indication for treatment with infliximab was loss of response or being refractory to immunosuppressants or to other biological drugs. Mean treatment duration with Remicade® was 33.5 months (17.25–63.75). The Remicade® dose had to be escalated in 10 patients, five of whom were still on the higher dose prior to switching.

At the time of switching, all patients were in clinical remission, with a median of 10 months (6–19). At the time of switching, 69.4% of patients were taking concomitant immunosuppressants. 83.3% were in biological remission and 90.3% had detectable infliximab levels. ATI was measured in seven patients prior to switching and was undetectable in six of them (85.7%). Of the patients whose ATI levels were assessed, three had undetectable infliximab levels, including the patient with detectable ATI.

Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of the patients enrolled.

Baseline and demographic characteristics.

| Baseline and demographic characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Variables | n=36 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.3 (±15.7) |

| Gender (♀), n (%) | 21 (58.3) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 10 (27.8) |

| Type of IBD, n (%) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 13 (36.1) |

| Crohn's disease | 23 (63.9) |

| Disease duration, years, median (IR) | 10.5 (6.7–11.9) |

| Family history, n (%) | 5 (13.9) |

| UC location, n (%) | |

| Proctitis | 1 (7.7) |

| Left-sided colitis | 4 (30.8) |

| Extensive colitis/pancolitis | 8 (61.5) |

| CD location, n (%) | |

| Ileal | 6 (26.1) |

| Colic | 7 (30.4) |

| Ileocolic | 10 (43.5) |

| Upper GI involvement CD, n (%) | 1 (4.3) |

| CD pattern, n (%) | |

| Inflammatory | 17 (73.9) |

| Stenosing | 1 (4.3) |

| Fistulising | 5 (21.7) |

| Perianal disease, n (%) | 11 (30.6) |

| Extraintestinal manifestation, n (%) | 6 (16.7) |

| Previous surgery, n (%) | 15 (41.7) |

| Intestinal resection, n (%) | 9 (60) |

| Prior treatment with thiopurines, n (%) | 36 (100) |

| Prior treatment with ADA, n (%) | 11 (30.6) |

| Prior treatment with IFX, n (%) | 6 (16.7) |

| Indication of treatment with Remicade®, n (%) | |

| Refractory | 31 (86.1) |

| Perianal CD | 4 (11.1) |

| Prevention of post-surgical CD relapse | 1 (2.8) |

| Duration of treatment with Remicade®, months, median (IR) | 33.5 (17.25–63.75) |

| Intensification of Remicade®, n (%) | 10 (27.8) |

| Concomitant IS treatment at the time of switching, n (%) | 25 (69.4) |

| Biological remission at the time of switching, n (%) | 30 (83.3) |

| Time in clinical remission, months, median (IR) | 10 (6–19) |

| IFX levels at the time of switching, n (%) | |

| Detectable | 28 (90.3) |

| Not detectable | 3 (9.7) |

| Ab to IFX at the time of switching, n (%) | |

| Detectable | 1 (14.3) |

| Not detectable | 6 (85.7) |

| IFX levels at the time of switching, μg/ml, median (IR) | 3.4 (1.2–7.2) |

| Hb at the time of switching, g/dl, median (IR) | 13.9 (13.2–14.6) |

| CRP at the time of switching, mg/l, median (IR) | 2.75 (0.9–5.4) |

Ab: antibody; ADA: adalimumab; CD: Crohn's disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; Hb: haemoglobin; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IFX: infliximab; IR: interquartile range; IS: immunosuppressant; SD: standard deviation; UC: ulcerative colitis; upper GI: upper gastrointestinal tract.

The mean duration of patient follow-up was 8.4 months (±3.5). Five patients (13.9%) had loss of response during follow-up (two with UC and three with CD), with a mean time to relapse of 2.4 months (±1.9). Mean CRP at the time of relapse was 13.77mg/dl (±19), with mean infliximab levels of 0.11μg/ml (±0.12). Of the five patients who relapsed, three were administered a higher dose of biosimilar infliximab, one was administered corticosteroids and another underwent perianal surgery. All five patients went back into clinical remission.

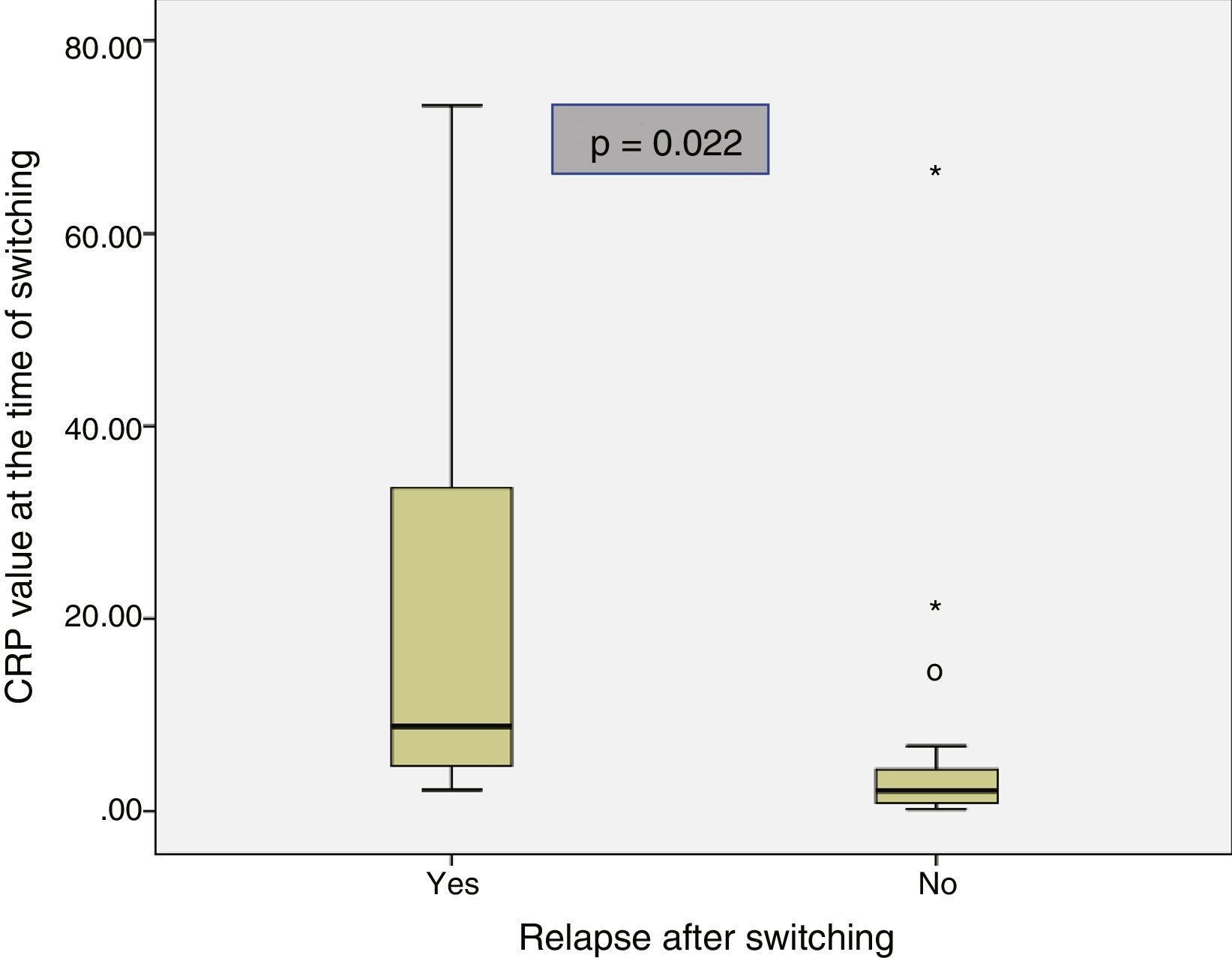

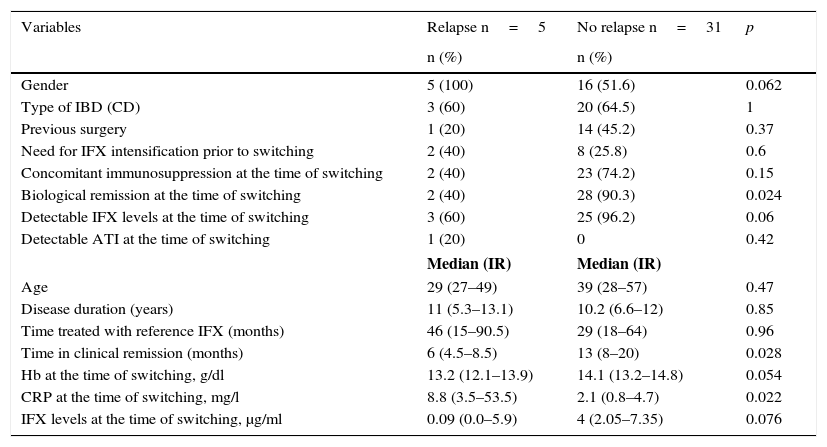

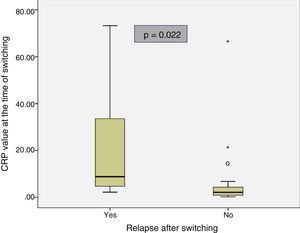

The baseline characteristics of the patients who relapsed and of those who remained in remission after switching are shown in Table 2. Median disease duration was similar in patients who relapsed compared to the group that remained in remission (11 years [5.3–13.1] vs 10.2 [6.6–12]; p=0.85). The median time in clinical remission prior to switching was higher in patients who remained in remission than in those who relapsed (13 months [8–20] vs 6 months [4.5–8.5]; p=0.028). The prevalence of biological remission at the time of switching was lower in the group of patients who relapsed compared to those who continued in remission (40% vs 90.3%; p=0.024). The median CRP at the time of switching was higher in the patients who relapsed than in those who continued in remission (8.8mg/l [3.5–53.5] vs 2.1mg/l [0.8–4.7]; p=0.022) (Fig. 1). Despite the lack of significant differences, the trend was towards a lower prevalence of detectable infliximab levels at the time of switching in the group of patients that relapsed compared to those who remained in remission (60% vs 96.2%; p=0.06). A trend towards lower infliximab levels at the time of switching (0.09μg/ml [0.0–5.9] vs 4μg/ml [2.05–7.35]; p=0.076) was also observed in the group of patients that relapsed.

Baseline characteristics of the relapse and non-relapse groups after switching.

| Variables | Relapse n=5 | No relapse n=31 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | 5 (100) | 16 (51.6) | 0.062 |

| Type of IBD (CD) | 3 (60) | 20 (64.5) | 1 |

| Previous surgery | 1 (20) | 14 (45.2) | 0.37 |

| Need for IFX intensification prior to switching | 2 (40) | 8 (25.8) | 0.6 |

| Concomitant immunosuppression at the time of switching | 2 (40) | 23 (74.2) | 0.15 |

| Biological remission at the time of switching | 2 (40) | 28 (90.3) | 0.024 |

| Detectable IFX levels at the time of switching | 3 (60) | 25 (96.2) | 0.06 |

| Detectable ATI at the time of switching | 1 (20) | 0 | 0.42 |

| Median (IR) | Median (IR) | ||

| Age | 29 (27–49) | 39 (28–57) | 0.47 |

| Disease duration (years) | 11 (5.3–13.1) | 10.2 (6.6–12) | 0.85 |

| Time treated with reference IFX (months) | 46 (15–90.5) | 29 (18–64) | 0.96 |

| Time in clinical remission (months) | 6 (4.5–8.5) | 13 (8–20) | 0.028 |

| Hb at the time of switching, g/dl | 13.2 (12.1–13.9) | 14.1 (13.2–14.8) | 0.054 |

| CRP at the time of switching, mg/l | 8.8 (3.5–53.5) | 2.1 (0.8–4.7) | 0.022 |

| IFX levels at the time of switching, μg/ml | 0.09 (0.0–5.9) | 4 (2.05–7.35) | 0.076 |

ATI: antibodies to infliximab; CD: Crohn's disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; Hb: haemoglobin; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IFX: infliximab; IR: interquartile range.

40% of patients who relapsed were taking a concomitant immunosuppressant, compared to 74.2% of patients who remained in remission (p=0.15).

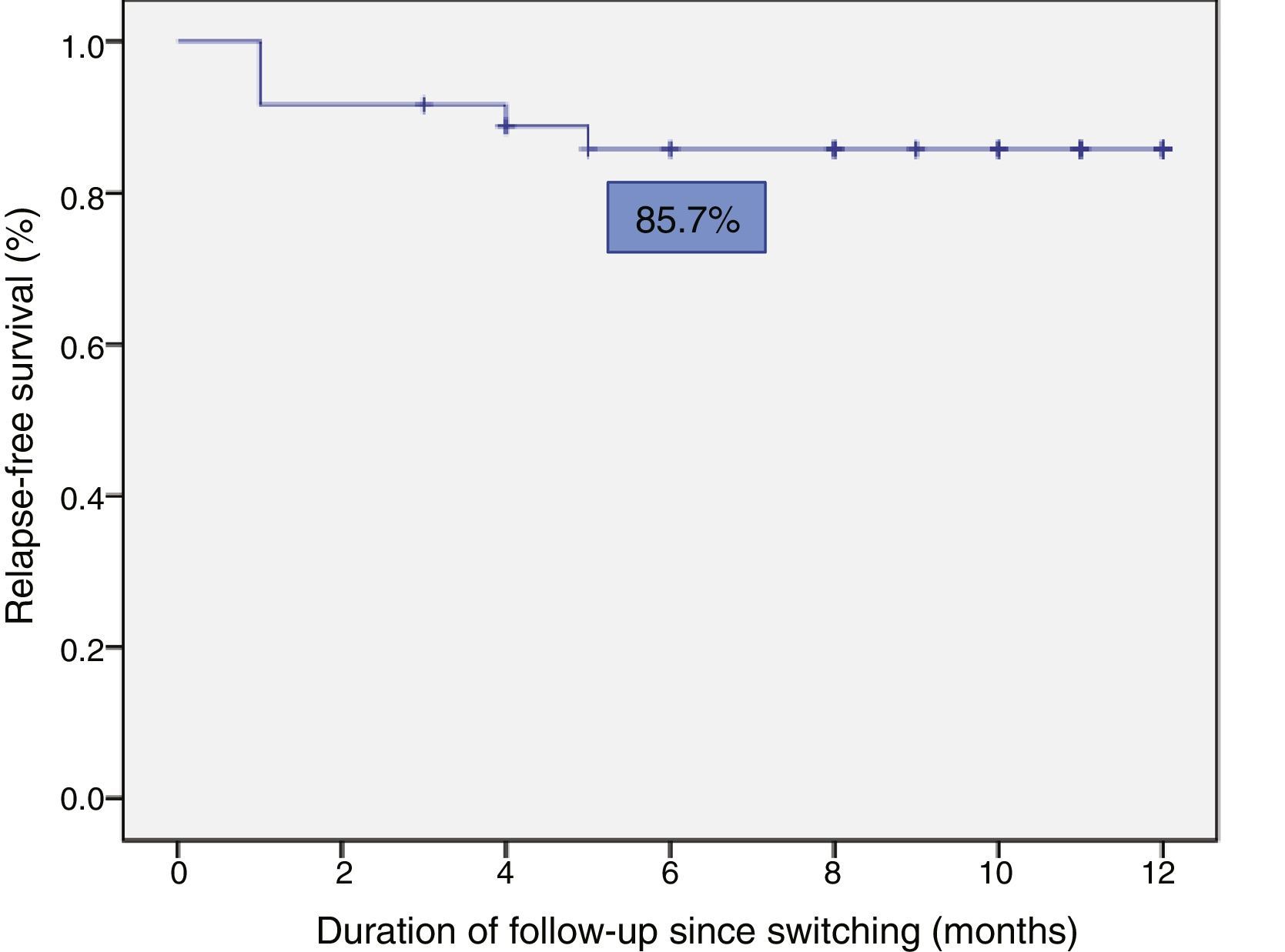

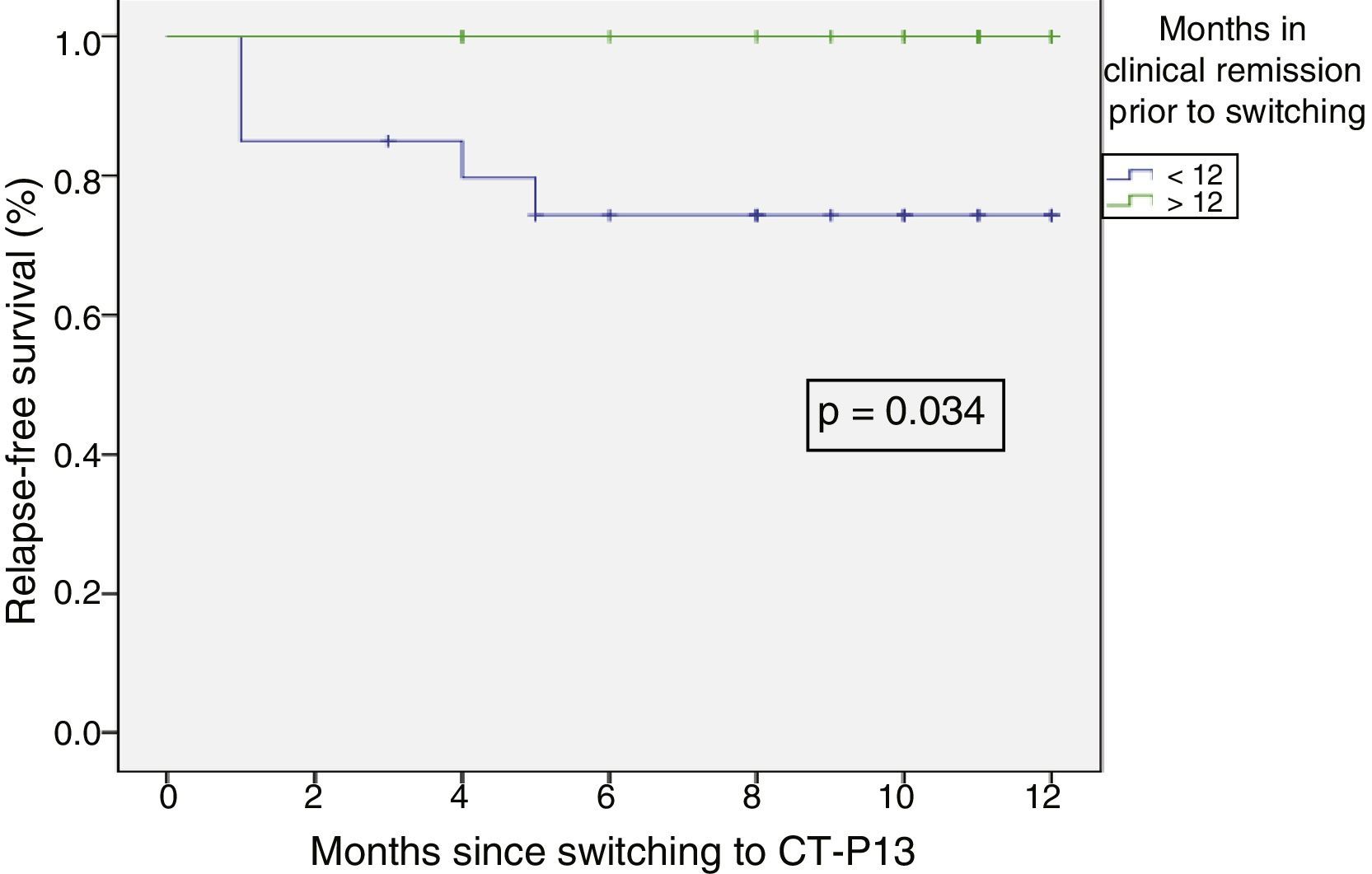

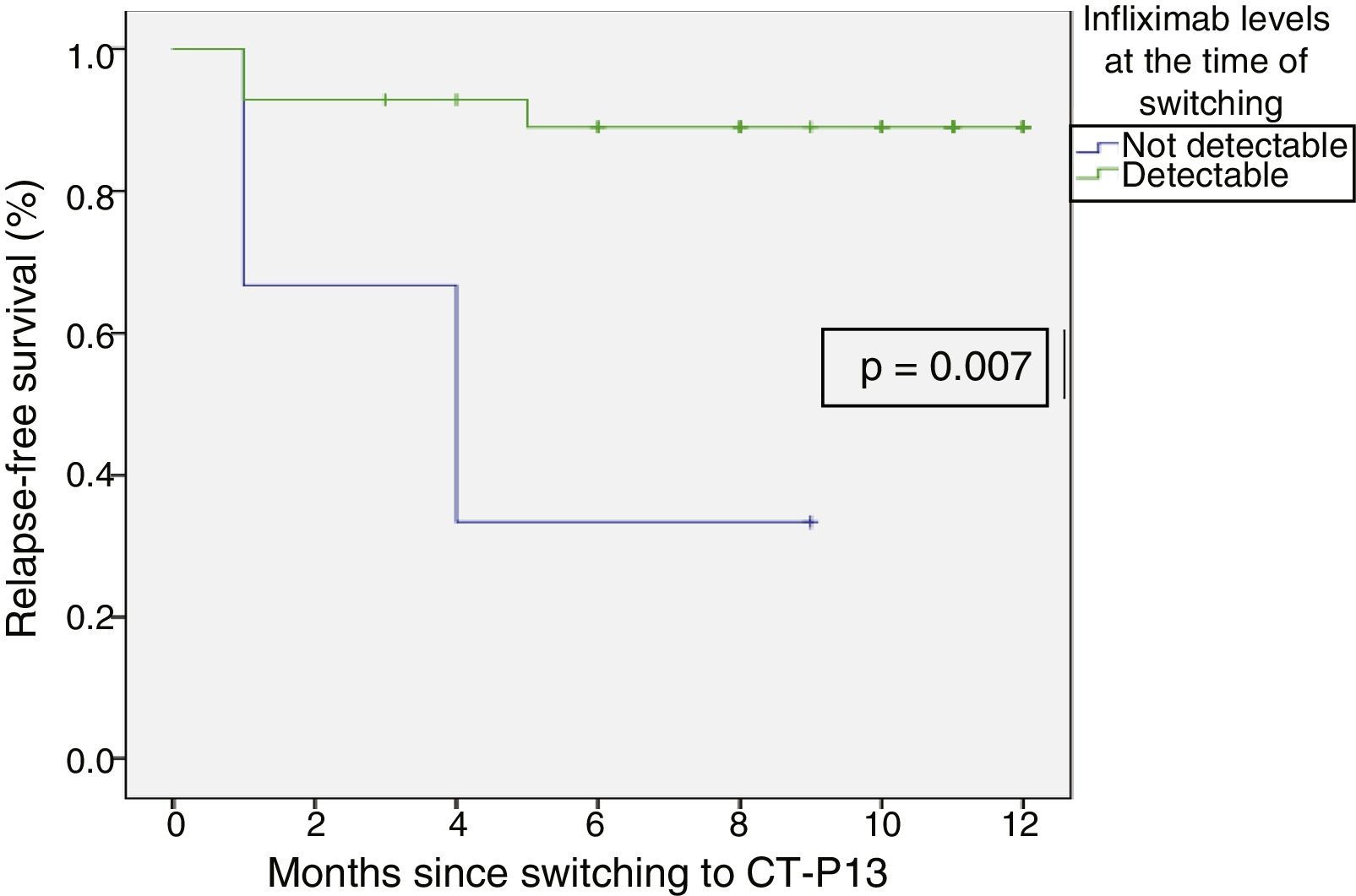

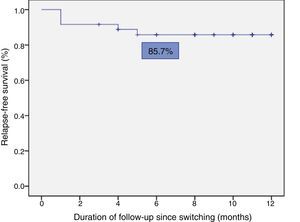

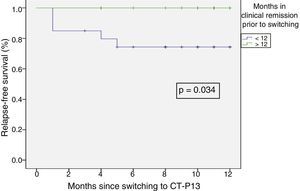

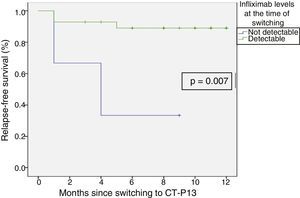

Relapse-free survival at six months follow-up was 85.7% (Fig. 2). This was significantly lower in patients who were in clinical remission for less than 12 months prior to switching, compared to those who had been in remission for more than 12 months (74.4% vs 100%; p=0.034) (Fig. 3). In addition, relapse-free survival at six months was lower in patients with undetectable infliximab levels at the time of switching compared to patients who had detectable levels of the drug (33.3% vs 89%; p=0.007) (Fig. 4).

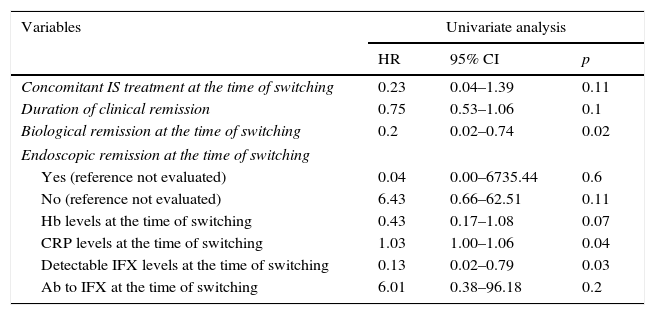

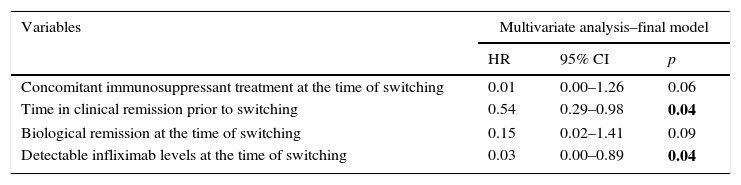

In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, clinical remission duration prior to switching (HR=0.54; 95% CI=0.29–0.98; p=0.043) and detectable infliximab levels (HR=0.03; 95% CI=0.00–0.89; p=0.043) were correlated with a lower risk of relapse. Concomitant immunosuppressant treatment (HR=0.015; 95% CI=0.00–1.26; p=0.06) and biological remission (HR=0.15; 95% CI=0.02–1.41; p=0.09) remained in the final Cox model as they were identified as confounding factors. The univariate Cox regression is shown in Table 3 and the final model is summarised in Table 4. Neither age, type of IBD, previous surgery, disease duration, duration of treatment with reference infliximab, prior need to escalate the dose nor the presence of ATI were associated with a risk of relapse.

Univariate Cox regression.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Concomitant IS treatment at the time of switching | 0.23 | 0.04–1.39 | 0.11 |

| Duration of clinical remission | 0.75 | 0.53–1.06 | 0.1 |

| Biological remission at the time of switching | 0.2 | 0.02–0.74 | 0.02 |

| Endoscopic remission at the time of switching | |||

| Yes (reference not evaluated) | 0.04 | 0.00–6735.44 | 0.6 |

| No (reference not evaluated) | 6.43 | 0.66–62.51 | 0.11 |

| Hb levels at the time of switching | 0.43 | 0.17–1.08 | 0.07 |

| CRP levels at the time of switching | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | 0.04 |

| Detectable IFX levels at the time of switching | 0.13 | 0.02–0.79 | 0.03 |

| Ab to IFX at the time of switching | 6.01 | 0.38–96.18 | 0.2 |

Ab: antibody; CRP: C-reactive protein; Hb: haemoglobin; IFX: infliximab; IS: immunosuppressant.

Multivariate Cox regression showing predictive factors of relapse-free survival after switching to biosimilar infliximab.

| Variables | Multivariate analysis–final model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Concomitant immunosuppressant treatment at the time of switching | 0.01 | 0.00–1.26 | 0.06 |

| Time in clinical remission prior to switching | 0.54 | 0.29–0.98 | 0.04 |

| Biological remission at the time of switching | 0.15 | 0.02–1.41 | 0.09 |

| Detectable infliximab levels at the time of switching | 0.03 | 0.00–0.89 | 0.04 |

In bold, significant p<0.05.

Only one patient presented transitory detectable ATI prior to switching from Remicade® to CT-P13 (Remsima®). No antibodies were found in subsequent blood tests after switching and the patient continued in clinical remission without requiring intensification of the biosimilar treatment.

In terms of infliximab levels, no differences were found between pre-switching levels and those measured at weeks 8 and 16 of follow-up (6.27μg/ml [±4.53] vs 6.42μg/ml [±4.78] vs 6.3μg/ml [±4.86]; p=0.94).

SafetyDuring follow-up, three patients (8.3%), all with Crohn's disease, experienced one or more adverse effects. In total, four adverse effects were observed: two upper respiratory tract infections, one odontogenic infection and one pneumonia, the latter being the only serious adverse effect observed that required Remsima® to be withdrawn. Most adverse effects occurred during the second and third months after switching. Biosimilar infliximab was suspended in three patients during follow-up (between four and six months after switching) owing to prolonged remission.

No cases of infusion reactions, malignancy or death were reported during follow-up.

DiscussionBiosimilar infliximab CT-P13 was approved by the EMA for the same indications as reference infliximab (Remicade®), and it is currently prescribed to induce response and remission in patients with moderate-severe CD and UC, with proven efficacy. However, clinical data on switching from Remicade® to CT-P13 in IBD are extremely limited.

This observational retrospective study presents the clinical experience of switching from reference infliximab (Remicade®) to CT-P13 (Remsima®) in patients with IBD at a single centre. Most patients (86.1%) remained in clinical remission during follow-up and few treatment-related adverse effects were reported. No changes in the bioavailability of infliximab or in the detection of ATI were identified during follow-up after switching.

In this study, 13.9% of patients presented with relapse or loss of efficacy to the anti-TNF treatment after switching, all of whom went back into clinical remission by means of various strategies (intensification, treatment with corticosteroids, surgery). The findings of this study are in line with the results reported by other investigators. A post-marketing study from South Korea that included 173 patients split into two groups (patients who switched to biosimilar infliximab vs patients who had not previously received reference infliximab), published the data of 46 patients (35 with CD and 11 with UC) from week 30 after switching. The study found that 82.8% of patients with CD and 100% of patients with UC did not experience a worsening of their disease.2 The objective of the NOR-SWITCH study, a randomised, double-blind, phase IV non-inferiority study funded by the Norwegian government, was to evaluate the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of switching to biosimilar CT-P13 compared to continuing treatment with reference infliximab (Remicade®) in various indications, including CD and UC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02148640).25 The data published from the NOR-SWITCH study, which included 481 patients (Remicade®: 241 and switching to CT-P13: 240), 155 with CD and 93 with UC followed-up for 52 weeks, showed that the disease worsened in 21.2% and 36.5% of patients with CD and 9.1% and 11.9% of patients with UC in the reference infliximab group and CT-P13 group, respectively. The results of this study suggest that switching to biosimilar CT-P13 is not inferior to continuing treatment with reference infliximab. Unlike our study, the NOR-SWITCH study included a control group of patients who continued with Remicade®, as well as a longer follow-up period. Nevertheless, the loss of efficacy data in the group of patients with UC that was administered CT-P13 (Remsima®) are similar to the findings of our study, although, in the CD group, the percentage of patients with worsening of the disease is higher. A prospective observational study of 83 patients with IBD who switched to CT-P13 published similar results to those obtained in our study, finding that 80% (CD) and 84% (UC) of patients remained in remission during follow-up.26 Similarly, another prospective, open-label study of 143 patients who switched to Remsima® found that 70% (CD) and 73% (UC) remained in remission during follow-up.27

In terms of predictive factors of relapse, longer clinical remission duration prior to switching and detectable infliximab levels at the time of switching were identified as factors associated with a lower risk of relapse after switching. Although no study published to date has evaluated the factors associated with the risk of relapse after switching to biosimilar infliximab, a systematic review of the factors that predict loss of response to infliximab, such as disease duration and location, the presence of ATI and undetectable infliximab levels, was recently published.28 As such, there are studies that suggest that infliximab levels predict the long-term prognosis of patients with CD and UC, thus supporting the findings of this study. In a study of 105 patients with CD treated with infliximab, the clinical remission rates were higher in patients with detectable infliximab levels than in those whose infliximab levels were undetectable, including patients without ATI (82% vs 6%; p<0.001).28,29 In support of these data, a post hoc analysis of ACCENT-1 found that an infliximab level ≥3.5μg/ml in week 14 was predictive of sustained remission at 54 weeks, with an OR of 3.5.28 In a cohort of 115 patients with UC, it was also found that detectable infliximab levels were associated with higher remission rates (69% vs 15%; p<0.001) and endoscopic improvement (76% vs 28%, p<0.001).30

This study identified four treatment-related adverse effects in three patients (8.3%), one of which (pneumonia) was classified as a serious adverse effect and led to the withdrawal of Remsima®. In the PLANETAS study, treatment-related adverse events were reported in 33 patients (39.3%) in the switching group during the extension study.13 CT-P13 was well tolerated, with a long-term safety profile consistent with the reference infliximab safety profile. In the PLANETRA study, treatment-related adverse events were reported in 27 patients (18.9%) in the switching group during the extension study,12 with four patients (2.8%) from this group suffering serious adverse reactions. In the cohort of 60 patients (group switching to CT-P13) from the South Korean post-marketing study, six treatment-related adverse effects were observed, including one severe infusion reaction, one lung abscess and one anaphylactic reaction, leading to withdrawal of CT-P13 in those patients.2 The adverse effects observed in the NOR-SWITCH study, including infusion reactions, were similar in both the reference infliximab group and the CT-P13 group (69.7% and 68.3%, respectively), with one or more serious adverse effects occurring in 10% and 8.8% of patients, respectively. However, these findings refer to global data and the frequency of adverse effects by diagnosis has yet to be published.25

This study found no differences between infliximab levels prior to switching and those measured at weeks 8 and 16 of follow-up. Similar results have been reported in recent studies, including the prospective, open-label study of 143 patients with IBD who switched to Remsima®, in whom no changes in infliximab levels were identified during follow-up (6.7μg/ml at the time of switching and 8μg/ml in the third month in patients with CD, 8.2μg/ml at the time of switching and 8.3μg/ml in the third month in patients with UC; p=0.54).27 Likewise, the NOR-SWITCH study also found similar levels of the drug in the Remicade® and CT-P13 groups during follow-up.25 However, a prospective, observational cohort study of 83 patients who switched to CT-P13 found that median infliximab levels increased from 3.5μg/ml (0–18) to 4.2μg/ml (0–21) in week 16 (p=0.010).26

This study has certain limitations, such as the small sample size, short follow-up and the fact that it is a retrospective study, which may have introduced bias and heterogeneity. Furthermore, the data were collected from a single centre and the study design did not include a control group of patients who continued treatment with reference infliximab (Remicade®). This may have weakened certain aspects of the analysis as it is difficult to ascertain whether changes in efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics may be due to switching to CT-P13 (Remsima®) or attributable to the natural course of the disease. Nevertheless, this study is based on routine clinical practice, which minimises selection bias, and, despite the limitations mentioned, our results are in line with expected findings.

In conclusion, switching to biosimilar infliximab in a real-life cohort of patients with IBD in clinical remission does not seem to have a significant impact on short-term clinical outcomes. The factors associated with relapse were similar to those expected during follow-up in patients who continued with the reference product. However, until prospective and controlled data become available, these findings in clinical practice should be interpreted with caution.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Guerrero Puente L, Iglesias Flores E, Benítez JM, Medina Medina R, Salgueiro Rodríguez I, Aguilar Melero P, et al. Evolución tras el intercambio a infliximab biosimilar en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal en remisión clínica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:595–604.