Infliximab (IFX) is effective in treating ulcerative colitis (UC) and in achieving mucosal healing (MH). Little is known about the role of mucosal healing (MH) in the subsequent evolution of the disease and the consequences of discontinuing treatment.

AimsTo evaluate the characteristics and evolution of patients with UC treated with IFX who discontinued treatment after disease remission.

MethodsObservational, prospective study of patients with moderate to severe UC, corticosteroid-resistant/corticosteroid-dependent, naïve to anti-TNF. IFX administration regimen: 5mg/kg at 0-2-6 weeks and every 8 weeks thereafter until week 54. In patients achieving MH, IFX was discontinued and the patients were followed-up for at least 20 months. Clinical remission (CR): Mayo score <2; Clinical response: decrease in Mayo score of 3 points; MH: Mayo score 0-1; Deep remission: patient with CR and MH.

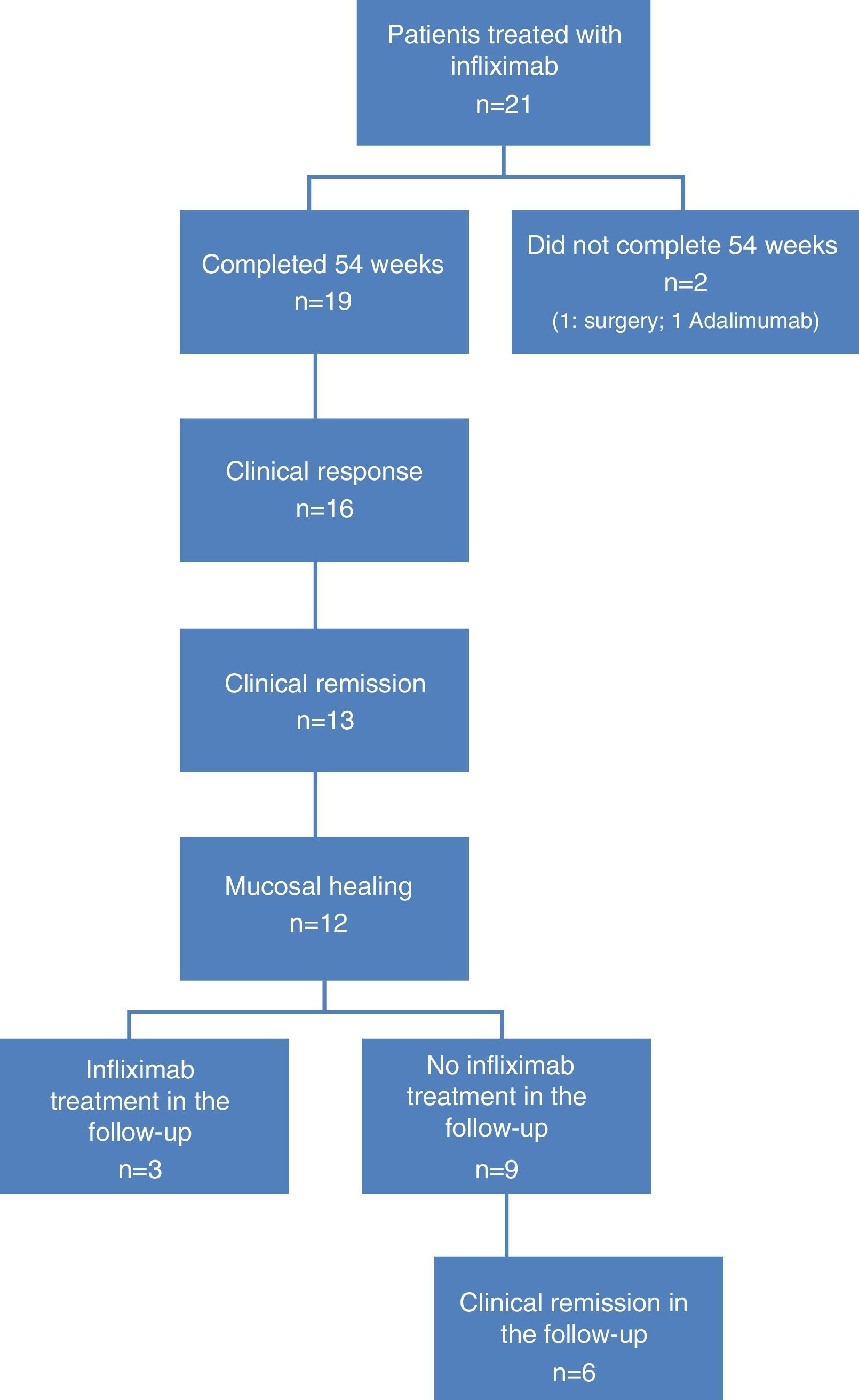

ResultsOf the 21 patients enrolled, 19 completed the study (colectomy, n=1; non-responder, n=1). Mean age: 47.8 years. UC: severe (n=13) and moderate (n=6); most patients (n=11) were steroid-resistant; 57.8% received combined treatment with immunosuppressants, and 31.5% intensified treatment. Week 54: 16 patients (84.2%) showed clinical response, 13 (68.4%) showed CR, and 12 (63.2%) deep remission. Of these, 6 (25%) presented a new episode of UC, and in 3 (25%) IFX was restarted within 12 weeks of discontinuation, with all patients responding. Of the total sample, 91.7% remained IFX-free at week 8, and 75% at week 12, with no remission during follow-up. None of the patients required hospitalisation or surgery.

ConclusionsHalf of patients with deep remission of UC with IFX therapy presented a new episode after treatment discontinuation, and in 25% IFX therapy was restarted.

Infliximab (IFX) es efectivo en la colitis ulcerosa (CU) y en obtener la curación de la mucosa (CM). Se conoce poco el papel que juega la CM en la evolución posterior de la enfermedad y qué ocurre una vez se interrumpe el tratamiento.

ObjetivosConocer las características y evolución de pacientes con CU tratados con IFX, que, tras obtener remisión profunda, suspenden el tratamiento.

MétodosEstudio observacional, prospectivo, de pacientes con CU moderada a grave, corticorresistente/corticodependiente, naïves a anti-TNF. Pauta de administración: IFX: 5mg/kg a 0-2-6 semanas y cada 8 después, hasta semana 54. En los pacientes que alcanzaron la CM, el tratamiento se interrumpió, con seguimiento posterior de al menos 20 meses. Remisión clínica (RC): puntuación Mayo<2; respuesta clínica: disminución de 3 puntos; CM: puntuación Mayo 0-1. Remisión profunda: paciente con RC y CM.

ResultadosDe los 21 pacientes incluidos, 19 completaron el estudio (colectomía=1; no respondedor=1). Edad media: 47,8 años. CU: grave (n=13); moderada (n=6), la mayoría, corticorresistentes (n=11). Un 57,8% recibieron tratamiento combinado con inmunosupresores y en el 31,5% el tratamiento se intensificó. Semana 54: 16 pacientes (84,2%) presentaron respuesta clínica, 13 (68,4%) RC y 12 (63,2%) remisión profunda. De ellos, 6 (50%) tuvieron un nuevo episodio de CU y 3 (25%) fueron tratados de nuevo con IFX. Estos últimos, en las 12 primeras semanas de la retirada del fármaco y todos respondieron de nuevo. El 91,7% de los pacientes permanecían libres de IFX a las 8 semanas y el 75% a las 12, manteniéndose en esta situación durante el tiempo de seguimiento. Ninguno de los pacientes precisó ingreso ni cirugía durante el seguimiento.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con CU que obtuvieron RM con IFX, tras suspender el tratamiento presentaron nuevo brote en la mitad de los casos y el 25% precisaron tratamiento de nuevo con IFX.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that affects the rectum and parts of the colon. It generally occurs in young individuals, and presents in the form of flare-ups and remission. The most common symptoms are bloody diarrhoea, defecatory urgency and rectal tenesmus.1

Although corticosteroids are the classic treatment in moderate-severe UC flare-ups, with cyclosporine being subsequently incorporated as rescue treatment, the need for early colectomy in UC seems to have remained unchanged.8

The quest for other treatment options for UC has increased significantly in the last 10 years, with the advent of biological drugs. Infliximab (IFX) was the first anti-TNF to show efficacy in the treatment of moderate-severe UC in patients who had not responded to or were dependent on corticosteroids, with or without immunosuppressants.2

In addition to controlling clinical activity, mucosal healing (MH) could today be considered a treatment objective in UC, given that it is an objective parameter for the control of intestinal inflammation. It has also been related with favourable clinical outcomes, as well as with less need for hospitalisation and surgery in these patients.3

MH is defined as absence of friability, blood, erosions and ulcers in any segment of the intestinal mucosa.1 IFX has also demonstrated efficacy in achieving MH in these patients.2

In this respect, the results of the ACT-1 study showed that treatment with IFX enabled MH to be achieved at week 54 in more than half of patients (60.3%), and that the subsequent clinical outcome was better in these patients than in those with no MH.4

However, further management with anti-TNF therapy in UC once the treatment objective has been reached has not yet been defined, in contrast to Crohn disease (CD), in which the outcome of patients in remission after 1 year on IFX therapy has been studied. Approximately half of patients in the study by Louis et al. presented relapse within 1 year after treatment discontinuation. The authors found that factors such as male gender, absence of previous surgical resection, leucocyte count>6×109/L, haemoglobin≤145g/L, C-reactive protein (CRP)≥5mg/L and faecal calprotectin≥300μg/g were associated with a risk of relapse. In patients with 2 or fewer risk factors, the risk of relapse was only 15% within 1 year after discontinuation of the drug.5

Although UC is a chronic process, the possible long-term side effects of biological drugs and their high cost mean that their withdrawal must be considered once the therapeutic objective has been reached.5 However, there is little information available to clinicians on the role played by deep remission in subsequent disease evolution and in particular, on what happens in these patients after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy, or if they need to be retreated with this drug.

Study objectives: (a) primary objective: to determine the clinical outcome after discontinuing IFX in patients with UC who have achieved deep remission; (b) secondary objectives: assessment of the factors associated with remission; response to retreatment with IFX; and colectomy-free evolution and hospitalisation.

Materials and methodsStudy design and objectivesDesign: Prospective observational study in corticosteroid resistant/dependent anti-TNF naive patients with moderate or severe UC. The study was conducted in the gastroenterology department of Hospital Universitario de Basurto (Bilbao, Spain) between April 2010 and February 2014 in both inpatients and outpatients. Both the study protocol and informed consent were approved by the hospital ethics committee, and all patients gave their written authorisation.

The study was carried out in 2 phases:

- 1.

First phase: Patients diagnosed with UC received treatment with IFX 5mg/kg at weeks 0, 2 and 6 and at least every 8 weeks thereafter until week 54. Treatment was escalated by shortening the infusion time from 8 to 6 weeks. Prior to receiving IFX, all patients were premedicated with 100mg of i.v. hydrocortisone and 5mg of i.v. dexchlorpheniramine. Endoscopy was performed immediately before initiating treatment and after completing treatment at week 54.

- 2.

Second phase: IFX treatment was discontinued in patients who achieved deep remission at week 54, and they were followed up clinically every 3 months for at least 20 months. Clinical assessment was performed using the Mayo 0 to 9 subscore.

The study included adults diagnosed with moderate or severe UC, refractory to conventional treatment with oral or intravenous corticosteroids or corticosteroid-dependent with or without combined thiopurine immunosuppressants (6-mercaptopurine/azathioprine), who had not previously received anti-TNF. Patients who had previously undergone colon surgery were excluded.

Diagnosis of UC: UC was diagnosed using Lennard-Jones criteria.1

Extent of disease: extent was determined according to the Montreal classification into 3 categories: rectitis, left-sided colitis and extensive colitis.6

Corticosteroid resistance: defined as persistent disease activity despite treatment with 0.75mg/kg/day of oral prednisone for 2 weeks. Patients with severe UC who received i.v. corticosteroids were considered to be corticosteroid-resistant if there was no response within the first 5 days.7

Corticosteroid dependence: defined as inability to taper the corticosteroid dose equivalent to 10mg of prednisone per day within 3 months from starting steroid treatment without relapse, or relapse within 3 months after discontinuation of corticosteroids.8

Patient assessmentClinical assessment was performed using the Mayo score (range: 0–12), which is the sum of the scores of 4 variables, 3 of which are clinical: stool frequency higher than normal (0–3), rectal bleeding (0–3) and physician global assessment (0–3) which make up the clinical subscore, and can have a total score of between 0 and 9.9 The fourth variable is endoscopy, which is scored from 0 to 3, and is considered the endoscopic subscore.10

The Mayo score was followed up at weeks 0 and 54, and subsequently, with the Mayo subscore every 12 weeks or earlier if the patient presented symptoms.

Definitions: (1) clinical remission (CR): Mayo subscore<2 and blood in faeces 0; (2) clinical response: decrease of at least 3 points in the Mayo subscore and blood in faeces 0 or 1; (3) sustained remission or response: obtained at week 8 and at week 54; (4) recurrence: need for corticosteroid treatment, retreatment with IFX or need for surgery. The mucosa was assessed with the Mayo endoscopic subscore (0–3) at the start of the study; (5) MH: Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1; (6) deep remission: patient with CR and MH.

Statistical analysisA descriptive study was performed. Quantitative variables are shown with the corresponding mean, with minimum and maximum ranges between parenthesis. The categorical variables are presented with their frequencies and percentage, with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Similarly, the Chi-squared test was used for the univariate analysis, and Pearson correlation for dependent variables. In patients with deep remission, a Kaplan–Meier survival curve was calculated to assess the anti-TNF treatment-free outcome. Using Cox regression, the following variables associated with anti-TNF-free outcome were analysed: sex, age, smoking habits, years since disease onset, extent, grade of mucosal lesion at the time of IFX discontinuation and immunomodulatory treatment. Results were analysed with the SPSS program, version 20.0. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsPatient characteristicsA total of 21 patients were included, 19 of whom completed the 54 weeks of IFX treatment. Reasons for non-completion were colectomy at week 12 in 1 patient, and no response to treatment at week 24 in another. Twelve patients were men (63.1%), with a mean age of 47.8 years (range: 31–82).

At the time of inclusion, a total of 13 patients (68.4%) had severe UC and 6 (31.6%) had moderate UC. Fig. 1 shows the flow algorithm of the patients analysed.

Treatment was indicated for corticosteroid resistance in 11 cases (57.8%), and more than half of patients (n=11, 57.8%) received combined treatment with immunosuppressants. IFX treatment escalation was necessary in 6 patients (31.6%).

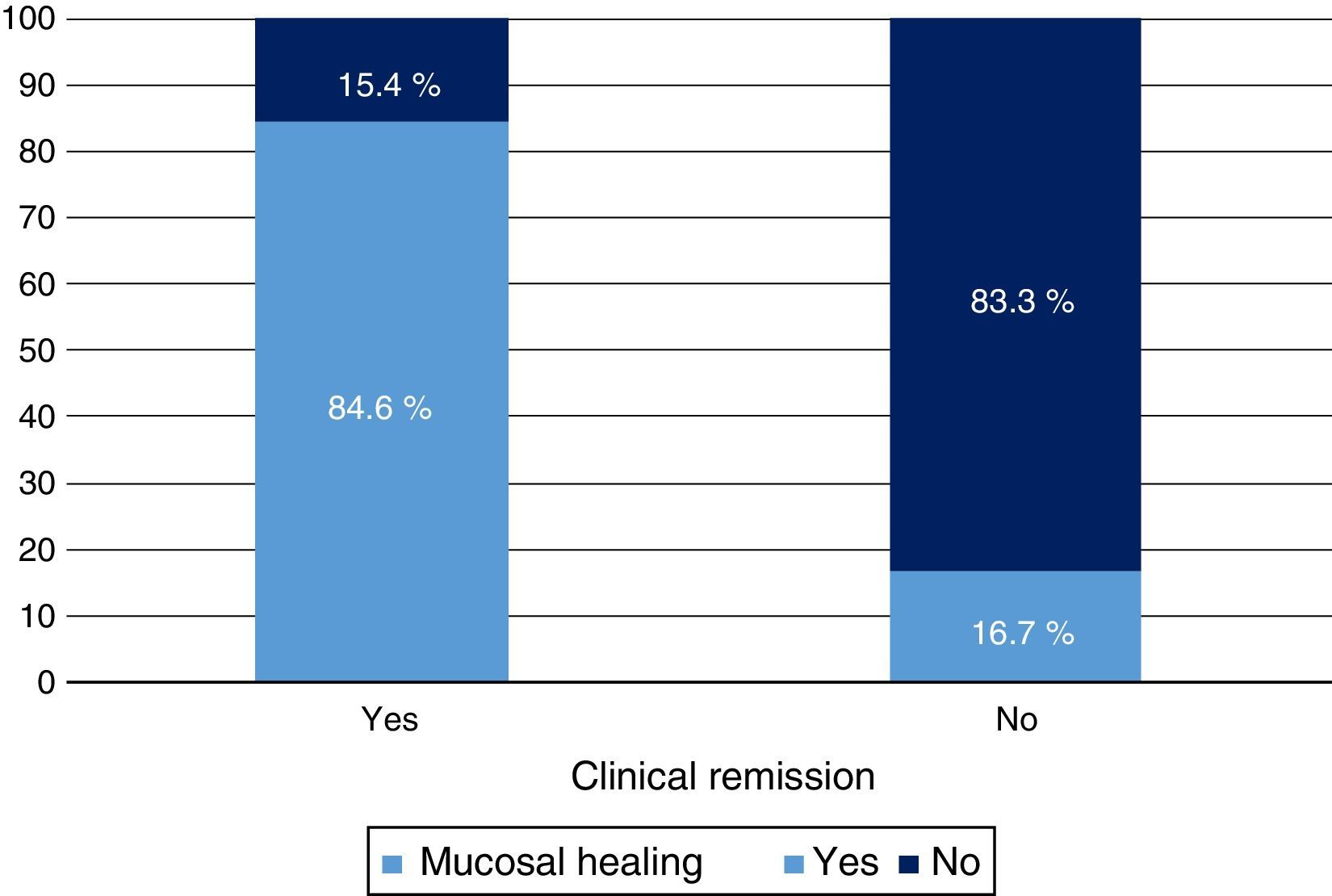

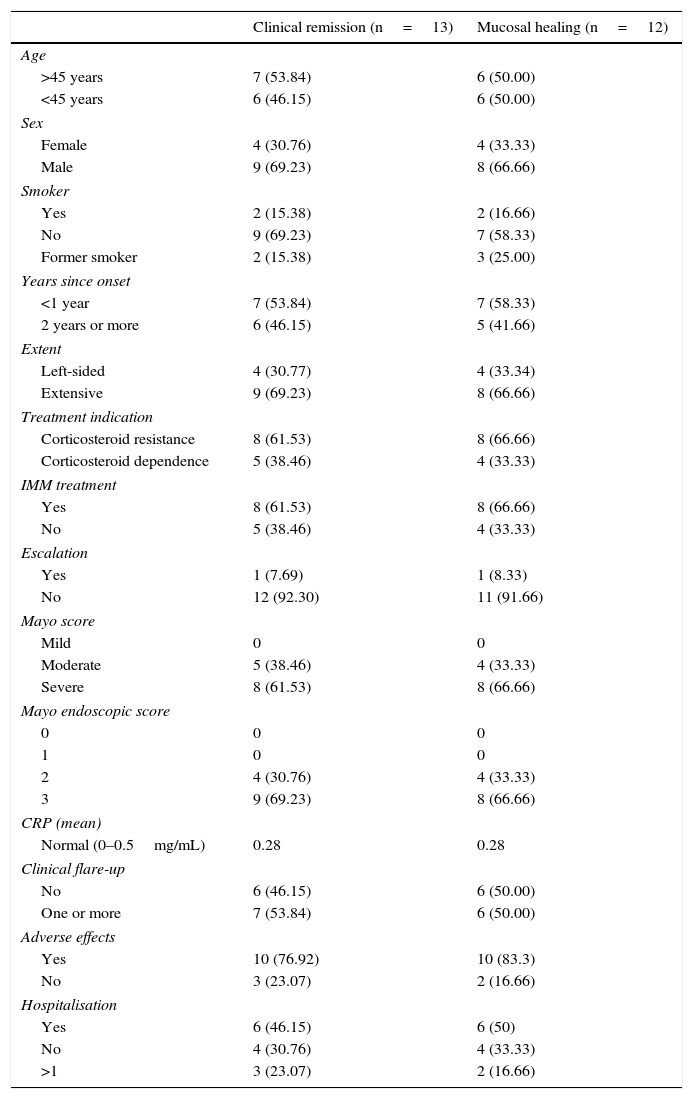

Clinical response and mucosal healing after one year of infliximab treatmentAt week 54, a total of 13 patients presented CR (68.4%; 95% CI: 47.5–89.3) and 16 (84.2%; 95% CI: 67.8–100) presented clinical response. With respect to the mucosa, 12 patients (63.2%; 95% CI: 41.5–84.9) presented deep remission (MH and CR) (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Clinical characteristics of patients with remission and mucosal healing.

| Clinical remission (n=13) | Mucosal healing (n=12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| >45 years | 7 (53.84) | 6 (50.00) |

| <45 years | 6 (46.15) | 6 (50.00) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 4 (30.76) | 4 (33.33) |

| Male | 9 (69.23) | 8 (66.66) |

| Smoker | ||

| Yes | 2 (15.38) | 2 (16.66) |

| No | 9 (69.23) | 7 (58.33) |

| Former smoker | 2 (15.38) | 3 (25.00) |

| Years since onset | ||

| <1 year | 7 (53.84) | 7 (58.33) |

| 2 years or more | 6 (46.15) | 5 (41.66) |

| Extent | ||

| Left-sided | 4 (30.77) | 4 (33.34) |

| Extensive | 9 (69.23) | 8 (66.66) |

| Treatment indication | ||

| Corticosteroid resistance | 8 (61.53) | 8 (66.66) |

| Corticosteroid dependence | 5 (38.46) | 4 (33.33) |

| IMM treatment | ||

| Yes | 8 (61.53) | 8 (66.66) |

| No | 5 (38.46) | 4 (33.33) |

| Escalation | ||

| Yes | 1 (7.69) | 1 (8.33) |

| No | 12 (92.30) | 11 (91.66) |

| Mayo score | ||

| Mild | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate | 5 (38.46) | 4 (33.33) |

| Severe | 8 (61.53) | 8 (66.66) |

| Mayo endoscopic score | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 (30.76) | 4 (33.33) |

| 3 | 9 (69.23) | 8 (66.66) |

| CRP (mean) | ||

| Normal (0–0.5mg/mL) | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Clinical flare-up | ||

| No | 6 (46.15) | 6 (50.00) |

| One or more | 7 (53.84) | 6 (50.00) |

| Adverse effects | ||

| Yes | 10 (76.92) | 10 (83.3) |

| No | 3 (23.07) | 2 (16.66) |

| Hospitalisation | ||

| Yes | 6 (46.15) | 6 (50) |

| No | 4 (30.76) | 4 (33.33) |

| >1 | 3 (23.07) | 2 (16.66) |

Adverse effects: infections, skin manifestations, arthralgias.

A significant relationship was observed between CR and MH variables both in terms of clinical response (p<0.05) and CRP value (p<0.01). Treatment escalation was predictive of no response or MH (p<0.01).

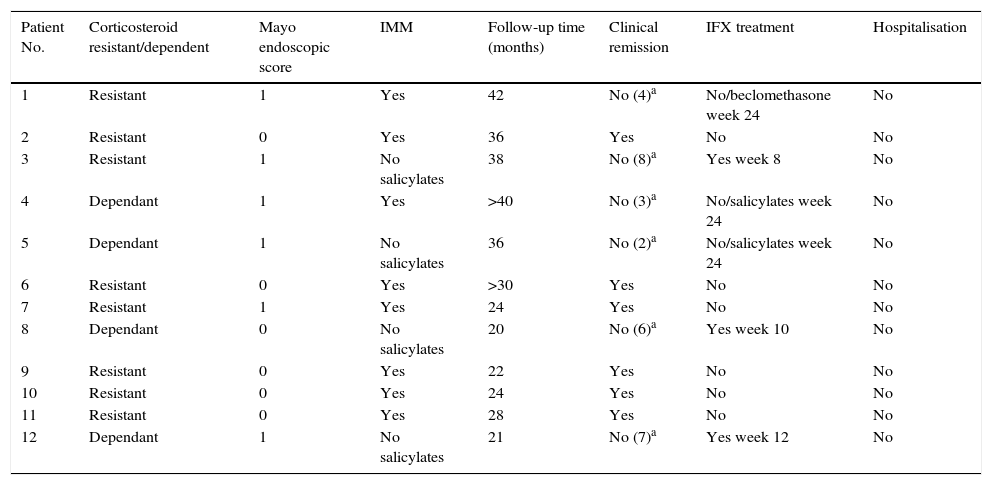

Evolution of patients with deep remission after discontinuing infliximab treatmentOf the 12 patients who presented deep remission at week 54, half presented a new episode of UC at 30.1 (42–20) months of follow-up after discontinuing IFX. Three of these (25%) with a severe flare-up (Mayo subscore: 8, 6 and 7) were retreated with IFX, 1 at week 8, another at week 10 and the other at week 12 of follow-up. In all 3 cases there was a new response to IFX treatment.

The other 3 patients who relapsed—2 at week 12 and 1 at week 24—presented a mild-moderate flare-up (Mayo subscore: 2, 3 and 4) and responded to treatment with salicylates in 2 cases and beclomethasone in the third.

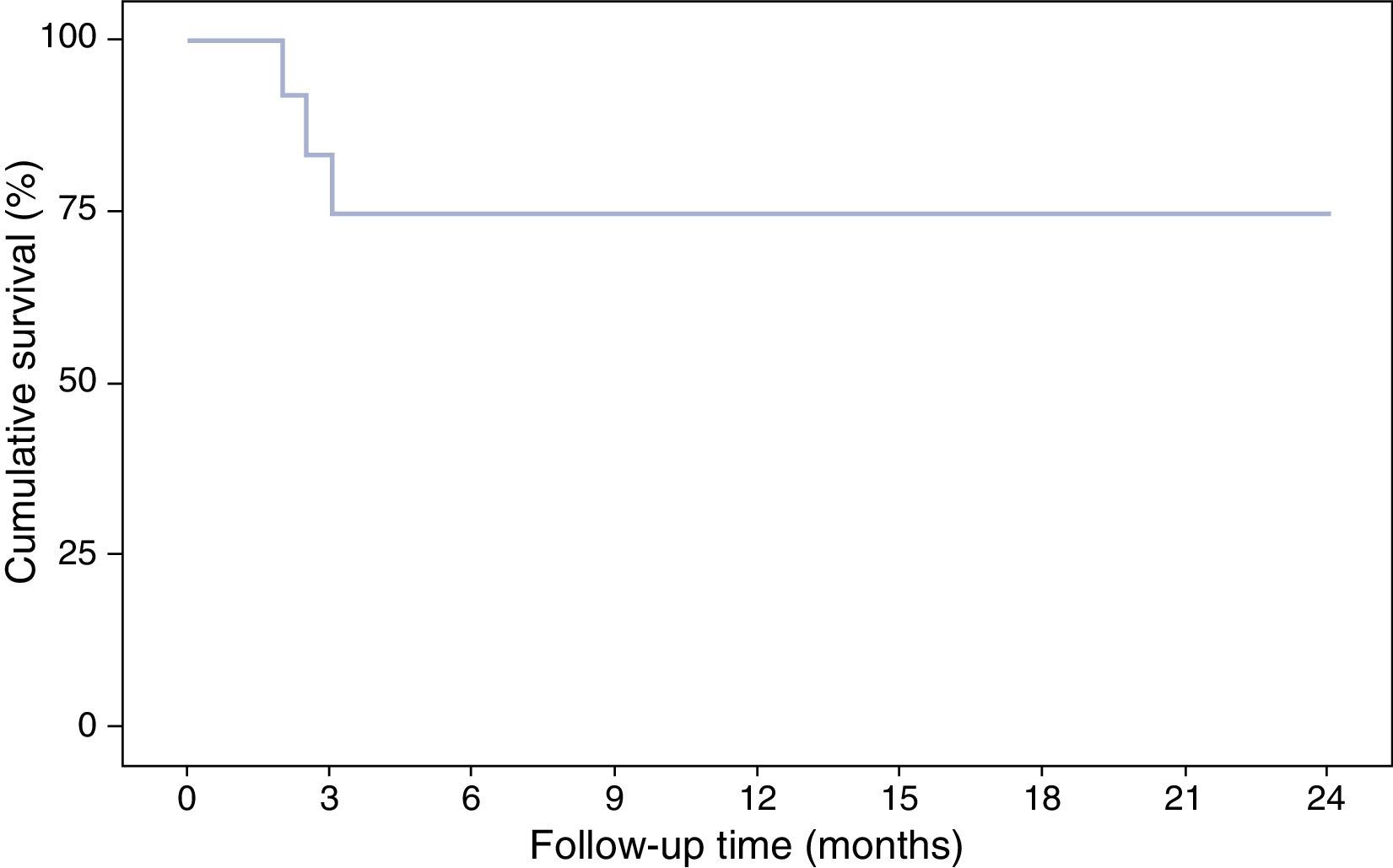

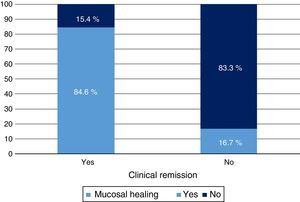

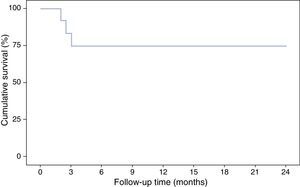

With respect to the interruption of biological treatment, 91.7% of patients remained IFX treatment-free at week 8 and 75% at week 12. This rate was maintained in the months of follow-up. During this time, no patient required either hospital admission or surgery (Table 2, Fig. 3). None of the variables analysed (sex, age, smoking status, disease extent, grade of mucosal lesion on discontinuing IFX or combined treatment with immunomodulators) met the criterion for significance (p>0.05).

Long-term evolution after discontinuing IFX in patients with deep remission.

| Patient No. | Corticosteroid resistant/dependent | Mayo endoscopic score | IMM | Follow-up time (months) | Clinical remission | IFX treatment | Hospitalisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Resistant | 1 | Yes | 42 | No (4)a | No/beclomethasone week 24 | No |

| 2 | Resistant | 0 | Yes | 36 | Yes | No | No |

| 3 | Resistant | 1 | No salicylates | 38 | No (8)a | Yes week 8 | No |

| 4 | Dependant | 1 | Yes | >40 | No (3)a | No/salicylates week 24 | No |

| 5 | Dependant | 1 | No salicylates | 36 | No (2)a | No/salicylates week 24 | No |

| 6 | Resistant | 0 | Yes | >30 | Yes | No | No |

| 7 | Resistant | 1 | Yes | 24 | Yes | No | No |

| 8 | Dependant | 0 | No salicylates | 20 | No (6)a | Yes week 10 | No |

| 9 | Resistant | 0 | Yes | 22 | Yes | No | No |

| 10 | Resistant | 0 | Yes | 24 | Yes | No | No |

| 11 | Resistant | 0 | Yes | 28 | Yes | No | No |

| 12 | Dependant | 1 | No salicylates | 21 | No (7)a | Yes week 12 | No |

Dependant: corticosteroid dependant; Resistant: corticosteroid resistant; IMM: immunomodulators; Salicyl: salicylates.

This study was conducted in patients with UC who achieved deep remission after 1 year of treatment with IFX. This subgroup of patients was selected as they were considered to have a low risk of recurrence after treatment discontinuation.11 During follow-up, 50% of patients presented disease activity, but only 25% required retreatment with IFX.

In another clinical study, which included both patients with Crohn disease and colitis, 40% of patients in deep remission continued in remission at the 20-month follow-up.12

IFX is an effective drug in the treatment of patients with UC who have not responded to treatment with either corticosteroids or immunosuppressants, and to obtain MH.2,13 Once the therapeutic objective has been reached, withdrawal of the drug might be considered, given that these are expensive drugs which in some cases have side effects. There is still insufficient evidence, however, to know when and in which patients it can be withdrawn. As on previous occasions, this situation has arisen in patients treated with biologics in rheumatology, and it has been found that in more than half of patients, the disease can be kept inactive after withdrawing the biological drug.14

MH is today considered a treatment objective, as it is related with favourable outcomes in both the short3 and long term.15 In the era prior to biologics, the results of a multicentre study conducted by the Ibsen group showed that patients with MH after 1 year of treatment had less clinical activity and less need for treatment,16,17 although the results of other clinical studies have been contradictory.18

Although we do not have a validated endoscopic score for assessing the MH,19 we followed—as in the pivotal studies—the Mayo subscore.2 MH is defined as a score of <1 (normal mucosa or with loss of vascular pattern, but without mucosal friability).20

In this study, MH was defined as a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 (normal mucosa) or 1 (mild inflammation). As Colombel et al. describe in a sub-analysis of the ACT-1 study, the degree of MH is related with the clinical outcome, and is better in grade 0 than in grade 1.3 In our case, 4 of the 6 patients who again presented clinical activity and 2 of the 3 who were retreated with IFX had an endoscopic score of 1. Although the sample size is too small to draw conclusions, it does show a tendency towards a poorer outcome. In any case, the degree of MH could be a factor of interest to take into account for future studies.

In this study, a period of 1 year of IFX treatment was estimated, taking as a reference the STORI trial and other clinical studies,21 which found this therapeutic approach to be appropriate.5 Recently, however, a committee of experts has recommended that these patients should remain in deep remission for at least 2 years before withdrawing treatment.22

In the subgroup of 12 patients with MH, IFX treatment was escalated in 4, increasing frequency from 8 to 6 weeks to obtain deep remission. With respect to combined treatment (IFX and azathioprine), this has been shown to be more effective for achieving MH.23 In the present study, combined treatment was administered in 8 of the 12 patients. Of the 4 who were not treated with immunomodulators, 1 presented a mild flare-up that responded to salicylates, and the remaining 3 required retreatment with IFX. Again, no conclusions could be drawn owing to the small sample size, but the results could suggest that combined treatment has a protective role against the need for retreatment with IFX, as previously described. The absence of immunomodulators was the only predictive factor of recurrence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.24 Other studies have not found this relationship, although they may also be limited by patient numbers.25,26 In our study, we did not find any factor related with recurrence, possibly limited by the small number of patients.

With respect to need for retreatment with IFX, the results of our study are similar to those described by other authors. Thus, in 3 retrospective studies in which IFX was discontinued after clinical remission, the percentage of patients who were retreated after 1 year ranged between 25%27 and 35%.28,29

Although the proportion of IFX-treatment free patients in this study remained stable at 75% during the follow-up, other authors have observed a gradual drop in treatment-free survival: 76%, 69% and 65% at 12, 24 and 36 months, respectively.30

In our patients, recurrences presented early on, within the first 12 weeks after discontinuation of IFX. This situation was also described in the STORI study, in which most relapses were observed in the first year.5 Similar findings have recently been reported in patients with inflammatory bowel disease who, like these patients, were also in deep remission.29

With respect to the response to retreatment with IFX, the outcomes were favourable in various studies, with responses of 71%27, 93%29 or 100%, as in our patients. In this sense, Laharie et al. found that patients with MH after IFX treatment had fewer treatment failures with new therapies.28 A protective role has also been found for immunosuppressants in this situation, as patients on treatment with these after withdrawal of IFX presented fewer infusion reactions in the retreatment.30

Another indication of good outcome in our patients is that colectomy was not required in any case, and there were no hospital readmissions during the study period.

Again, in the Laharie study, the absence of MH (Mayo score 2–3) was found to be the only factor related with colectomy.28

Although this study is limited by the small number of patients, we can conclude that, during the follow-up period in our patients with deep remission, 50% remained in disease remission and only 25% required retreatment with IFX. Furthermore, the 3 patients in the study who required retreatment with IFX again achieved a clinical response, without requiring hospital admission or colectomy in any case.

In summary, patients with UC treated with IFX who reach deep remission progress well after withdrawal of the drug, and cases who require retreatment with IFX again achieve clinical remission.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

We would like to thank Dr Sofía Perea for her assistance in drafting this manuscript, and Merck Sharp & Dohme España for financial support for this paper.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz Villafranca C, Bravo Rodríguez MT, Ortiz de Zárate J, Arreba González P, García Kamiruaga I, Heras Martín JI, et al. Evolución clínica tras la suspensión de infliximab en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa en remisión profunda. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:442–448.