The incidence of peptic ulcers (PU) has decreased in the last decades, although, complications of PU such as perforation and bleeding have remained fairly constant.1 Despite the improvement in endoscopic facilities, eradication of Helicobacter pylori and the introduction of the proton pump inhibitors (PPI), complications such as peptic ulcer perforation remain a substantial healthcare problem, probably due to the aging of our population and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).2 Perforation of a peptic ulcer is a serious complication which occurs in almost 10% of the cases of complicated ulcers and has an overall mortality of 10%.3 The pattern of perforated PU varies with prevailing sociodemographic and environmental factors, as in the developing world, the patient population is young with smoker male's predominance, while in the west countries, the patients tend to be elderly and medicated with ulcerogenic drugs.1 The diagnosis of perforated PU represents a diagnostic challenge in most cases because the spectrum of presentation is wide, however, most cases present with extraluminal air, pancreatitis, or lesser sac abscess.5 When the perforation is confined into an adjacent structure it is called penetration of a peptic ulcer.3,4 The most common site of penetration of duodenal ulcers is the pancreas (52.6%), followed by the biliary tract (18.4%), gastrohepatic omentum (10.7%), liver (6.2%), and colon (1.5%).4 Penetration to the liver is very rare and may lead to upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage or abscess formation.5 We report a case that illustrated this situation.

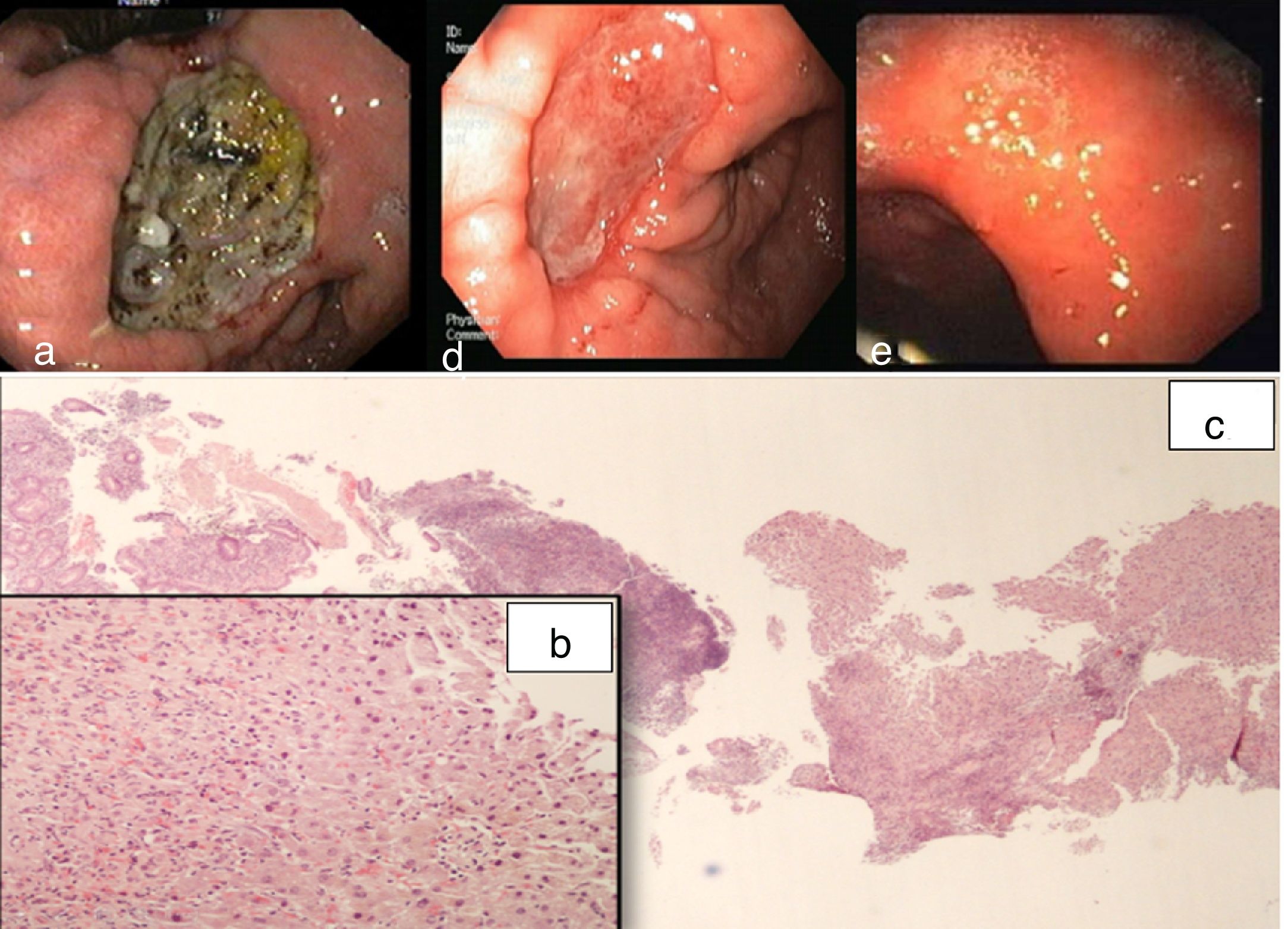

A 56-year-old female was admitted with one week duration epigastric pain and significant weigh lost (7kg). She had a past history of PU (fifteen years ago) and H. pylori (Hp) status was unknown. Currently she was not on any chronic medication, with exception of NSAID in the former two weeks because of back pain. She was apyretic, hemodynamically stable and presented with painful abdomen in epigastric region, without rebound tenderness. Laboratory tests: hemogram 12.7g/dL (previous 13.6g/dL), leucocytosis (17,560/mm3) and elevation of C reactive protein (6.1mg/dL); liver tests were unremarkable. Abdominal ultrasound showed a diffuse thickening of the gastric wall with adjacent multiple adenopathies. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) revealed an extensive ulceration (5cm) with irregular edges, in the lesser gastric curvature, involving incisura angularis and extending to the pylorus (Fig. 1a). Abdominal computed tomography was performed and showed a concentric and diffuse thickening of the gastric antrum wall without significant densification of the adjacent fat and fair-centimeter nodes in the small epiploon. The patient started IV pantoprazole (80mg/24h) and, after a positive urea breathing test, Hp was eradicated (accordingly to current guidelines). The patient was asymptomatic 48h after admission. She was discharged and re-evaluated in outpatient consultation 2 weeks later. She remained asymptomatic and had gained weight. At this time, the biopsies done in the UGIE were available and revealed distorted hepatic tissue with inflammatory changes (Fig. 1b and 1c). A second UGIE was performed (Fig. 1d) and showed a significant reduction on ulcer size; biopsies samples revealed granulation tissue compatible with ulcer base. The patient remained on PPI therapy for over a year and avoided NSAIDs without recurrence of complaints. Two years after this episode the patient was asymptomatic, has stopped PPI therapy and gastric mucosa was healed completely (Fig. 1e).

a) UGIE showing giant ulceration with irregular edges, in the lesser curvature; b) Gastric biopsy samples showing necrotic debris, mild active atrophic chronic gastritis and a fragment of hepatic tissue with active chronic inflammatory process, H&E, 20x; c) H&E, 400x. d) Second UGIE (15 days latter) showing ulcer healing; e) UGIE (2 years latter) showing complete healing of gastric mucosa.

Only a few cases of hepatic penetration by peptic ulcer disease endoscopically diagnosed have been reported.5 Like in this case, imaging methods were not conclusive and most presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding without abdominal pain.5 Hp infection and the use of NSAIDs were the identified risk factors for PU in this case. The reported most common endoscopic findings in this situation are giant ulcers that can mimic malignancy (as seen in our patient) and pseudotumoral mass protruding from the ulcer bed or a mass without ulcer4,5; the diagnosis also was established after endoscopic biopsies revealing hepatic tissue.4,5 The histological changes found in our patient are similar to those reported in literature4,5, which result from advanced peptic ulcer digestion, a process called peptic hepatitis.5 This usually does not result in changes in liver function tests.5 Therefore, abnormal results in this group of patients is of limited diagnostic value.4,5 The majority of patients required surgery for the management of hepatic penetration and in less than one third of the reported cases, medical conservative treatment was possible.4,5 In conclusion, we report a very rare complication of PU ulcer that requires a high index of suspicion for the diagnosis and in which the medical treatment was effective.

FundingNone.