Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is common and often difficult to manage. Faecal microbiota transplant (FMT) is an effective therapeutic tool in these cases, although its applicability and effectiveness in Spain is currently unknown.

AimTo analyse the technical aspects, safety and effectiveness of the first consolidated FMT programme in Spain.

MethodsRetrospective descriptive study of all patients with recurrent CDI treated with FMT performed by colonoscopy in a tertiary centre after the implementation of a multidisciplinary protocol between March 2015 and September 2016.

ResultsA total of 13 FMT were performed in 12 patients (11/12; 91.7% women) with a median age of 84.6 years (range: 38.2–98.2). Recurrence of CDI was the indication for FMT in all cases. Patients had suffered a median of 3 previous episodes of CDI (range: 2–6) and all had failed treatment with fidaxomicin. All procedures were performed by colonoscopy. Effectiveness with one session of FMT was 91.7% (11/12; 95% CI: 64.6–98.5%). In the non-responder patient, a second FMT was performed 17 days after the first procedure, with disappearance of symptoms. No side effects related to the endoscopic procedure or the FMT were recorded after a median follow-up of 6.5 months (range: 1–16 months). Two patients died during follow-up due to causes unrelated to FMT.

ConclusionFMT by colonoscopy is an effective and safe therapeutic alternative in recurrent CDI. It is a simple procedure that should be implemented in more centres in Spain.

La recurrencia de la infección por Clostridium difficile (ICD) es frecuente y a menudo difícil de controlar. El trasplante de microbiota fecal (TMF) es una opción terapéutica avalada en estos casos, aunque se desconoce su aplicabilidad y efectividad en nuestro medio.

ObjetivosAnalizar los aspectos técnicos, seguridad y efectividad del primer programa consolidado de TMF en España.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo descriptivo de todos los pacientes con ICD recurrente tratados mediante TMF por colonoscopia en un hospital de tercer nivel tras la implantación de un protocolo multidisciplinar entre marzo de 2015 y septiembre 2016.

ResultadosSe realizaron 13 TMF en 12 pacientes (11/12; 91,7% mujeres) con una mediana de edad de 84,6 años (rango: 38,2-98,2). En todos los casos la indicación fue la recurrencia de la ICD. Los pacientes habían presentado una mediana de 3 episodios previos de ICD (rango: 2-6) y en todos había fracasado el tratamiento con fidaxomicina. Todos los procedimientos se realizaron mediante colonoscopia. La efectividad con una sesión de TMF fue del 91,7% (11/12; IC 95%: 64,6-98,5%). En la paciente no respondedora se realizó un segundo TMF a los 17 días con desaparición de la sintomatología. No se registraron efectos adversos secundarios al procedimiento endoscópico ni al TMF tras una mediana de seguimiento de 6,5 meses (rango: 1-16 meses). Dos pacientes fallecieron durante el seguimiento por causas no relacionadas con el TMF.

ConclusionesEl TMF por colonoscopia es una alternativa terapéutica efectiva y segura en la recurrencia de la ICD. Se trata de un procedimiento sencillo que debería implementarse en más centros en nuestro entorno.

Clostridium difficile (CD) is the primary cause of nosocomial diarrhoea in the western world and is associated with high morbidity and mortality and use of healthcare resources.1 Classic treatment comprises the withdrawal of the offending antibiotic and the administration of metronidazole, vancomycin or, more recently, fidaxomicin. However, a significant number of patients fail to respond to initial treatment or suffer a recurrence (2–38%) in the first eight weeks.2

In 1958, Eiseman et al. published a series of four cases of pseudomembranous enterocolitis successfully treated with faecal enema.3 This approach, conceptually at odds with current thinking at the time that microbiota was a harmful entity, was forgotten about by the scientific community for more than half a century. It was not until the last decade, and the last five years in particular, that faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has established itself as one of the most talked-about treatments on a theoretical and practical level in the fields of gastroenterology, autoimmune processes and metabolic diseases. The clinical practice guidelines already include this therapeutic approach as an alternative treatment for recurrent CD infection (CDI) and clinical trials have been published that support its efficacy in inflammatory bowel disease.4–6 With the publication of the first trials of FMT in CDI, in 2013 we designed a multidisciplinary programme (Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Microbiology and Department of Infectious Diseases) at our centre. To date, no data have been published that evaluate the outcome of FMT in Spain. The objective of this study was to analyse the effectiveness and safety of FMT following the implementation of this programme.

Material and methodsStudy design and populationThis was a descriptive, retrospective study of all cases of FMT performed at Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal in Madrid (Spain) between March 2015 and September 2016 to treat recurrent CDI. FMT success was defined as a lack of diarrhoea (three or more bowel movements per day) in the eight weeks following the procedure.

Data collectionDemographic, clinical, analytical, microbiological and endoscopic variables were collected from the medical records and electronic database of the Endoscopy Unit (Endobase, Olympus®) using a specially-designed 48-item case report form. Both telephone interviews and the Horus healthcare information system, which can be used to view primary care appointments and reasons for consultation, were used for patient follow-up.

Description of the faecal microbiota transplantation protocolIndication for faecal microbiota transplantation (recipient)The Department of Infectious Diseases is primarily responsible for the clinical management of patients with CDI and usually establishes the indication for FMT. Given that fidaxomicin is given to patients with a high risk of recurrence or multiple recurrences of CDI, any patient who receives this drug is considered to be a potential candidate for FMT (Table 1). If the patient agrees to this treatment, he/she is referred to the Gastroenterology Clinic for donor screening. In the event of microbiologically-confirmed CDI recurrence after treatment with fidaxomicin, the patient is treated with vancomycin and the colonoscopy for FMT is scheduled. Vancomycin is withdrawn two days prior to the colonoscopy.

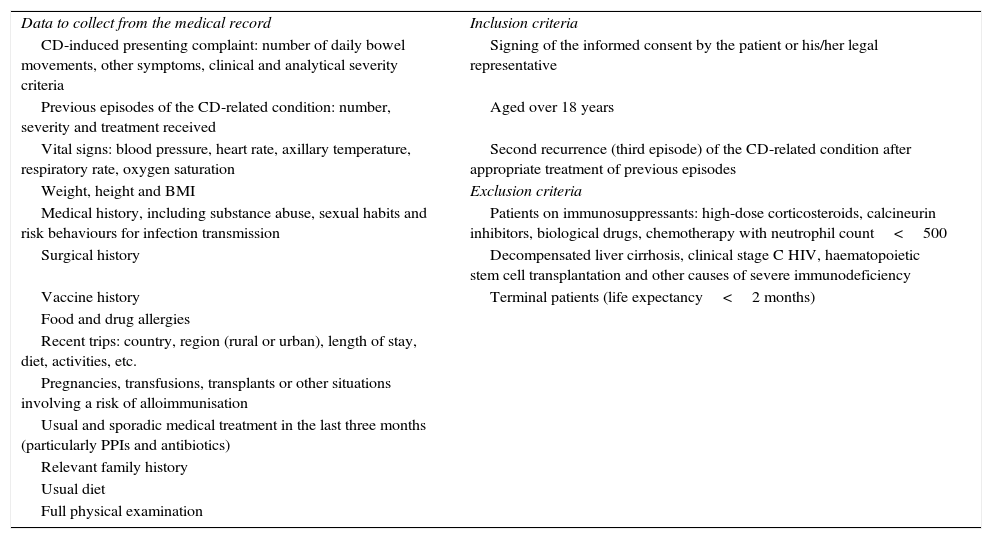

Screening criteria and data to be collected from the FMT recipient.

| Data to collect from the medical record | Inclusion criteria |

| CD-induced presenting complaint: number of daily bowel movements, other symptoms, clinical and analytical severity criteria | Signing of the informed consent by the patient or his/her legal representative |

| Previous episodes of the CD-related condition: number, severity and treatment received | Aged over 18 years |

| Vital signs: blood pressure, heart rate, axillary temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation | Second recurrence (third episode) of the CD-related condition after appropriate treatment of previous episodes |

| Weight, height and BMI | Exclusion criteria |

| Medical history, including substance abuse, sexual habits and risk behaviours for infection transmission | Patients on immunosuppressants: high-dose corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, biological drugs, chemotherapy with neutrophil count<500 |

| Surgical history | Decompensated liver cirrhosis, clinical stage C HIV, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and other causes of severe immunodeficiency |

| Vaccine history | Terminal patients (life expectancy<2 months) |

| Food and drug allergies | |

| Recent trips: country, region (rural or urban), length of stay, diet, activities, etc. | |

| Pregnancies, transfusions, transplants or other situations involving a risk of alloimmunisation | |

| Usual and sporadic medical treatment in the last three months (particularly PPIs and antibiotics) | |

| Relevant family history | |

| Usual diet | |

| Full physical examination |

BMI: body mass index; CD: Clostridium difficile; FMT: faecal microbiota transplantation; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PPI: proton-pump inhibitors.

The Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology is responsible for the outpatient assessment of potential donors (Table 2). Once the informed consent has been signed, a general medical history is taken, a clinical examination is performed and a specifically-designed questionnaire is completed (Table 3). If no contraindications are identified after this initial assessment, blood and stool samples are taken (Table 4). The pre-donation study is considered valid for three months after the first visit. The donor is instructed to inform the doctor responsible for the FMT of any relevant change in his/her clinical or epidemiological situation up to and including the day of the procedure. On the morning of the procedure, the donor must provide the Microbiology laboratory with a complete stool sample (as recent as possible). The FMT should ideally be conducted within the first 6h since defecation, and samples more than 24h old should not be used.7 At this time, the donor should be asked if he/she has experienced any symptoms of infection (fever, diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain) in the last few days, if he/she has consumed any foods in the last five days that the recipient is known or suspected to be allergic to or if he/she has recently taken any drug that could affect microbiota composition (mainly antibiotics). If the donor answers yes to any of these questions, the donation is invalid and the procedure must be cancelled.

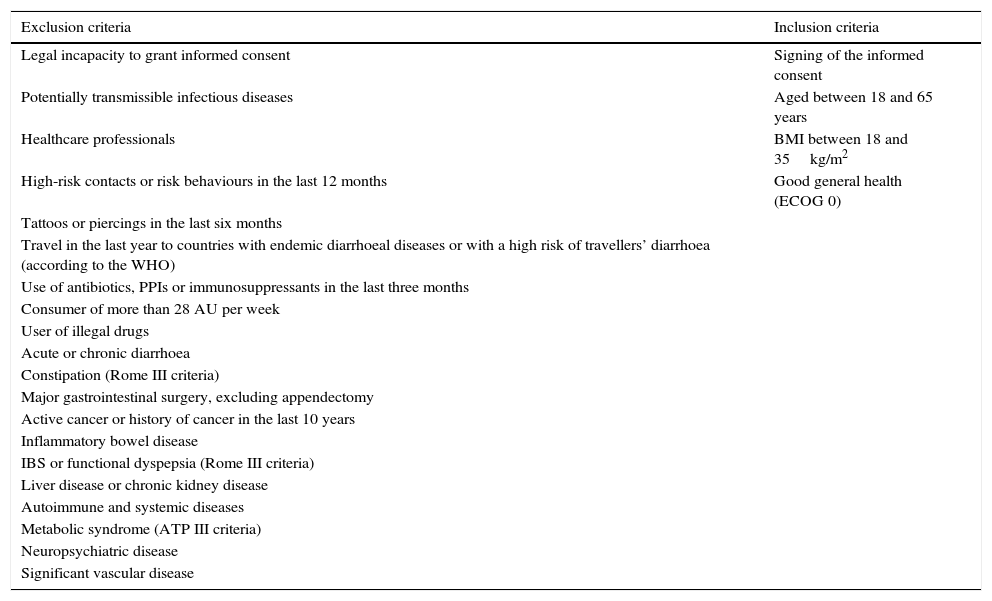

Donor inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Exclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Legal incapacity to grant informed consent | Signing of the informed consent |

| Potentially transmissible infectious diseases | Aged between 18 and 65 years |

| Healthcare professionals | BMI between 18 and 35kg/m2 |

| High-risk contacts or risk behaviours in the last 12 months | Good general health (ECOG 0) |

| Tattoos or piercings in the last six months | |

| Travel in the last year to countries with endemic diarrhoeal diseases or with a high risk of travellers’ diarrhoea (according to the WHO) | |

| Use of antibiotics, PPIs or immunosuppressants in the last three months | |

| Consumer of more than 28 AU per week | |

| User of illegal drugs | |

| Acute or chronic diarrhoea | |

| Constipation (Rome III criteria) | |

| Major gastrointestinal surgery, excluding appendectomy | |

| Active cancer or history of cancer in the last 10 years | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | |

| IBS or functional dyspepsia (Rome III criteria) | |

| Liver disease or chronic kidney disease | |

| Autoimmune and systemic diseases | |

| Metabolic syndrome (ATP III criteria) | |

| Neuropsychiatric disease | |

| Significant vascular disease |

ATP: Adult Treatment Panel; AU: alcohol units; BMI: body mass index; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; PPI: proton-pump inhibitors; WHO: World Health Organisation.

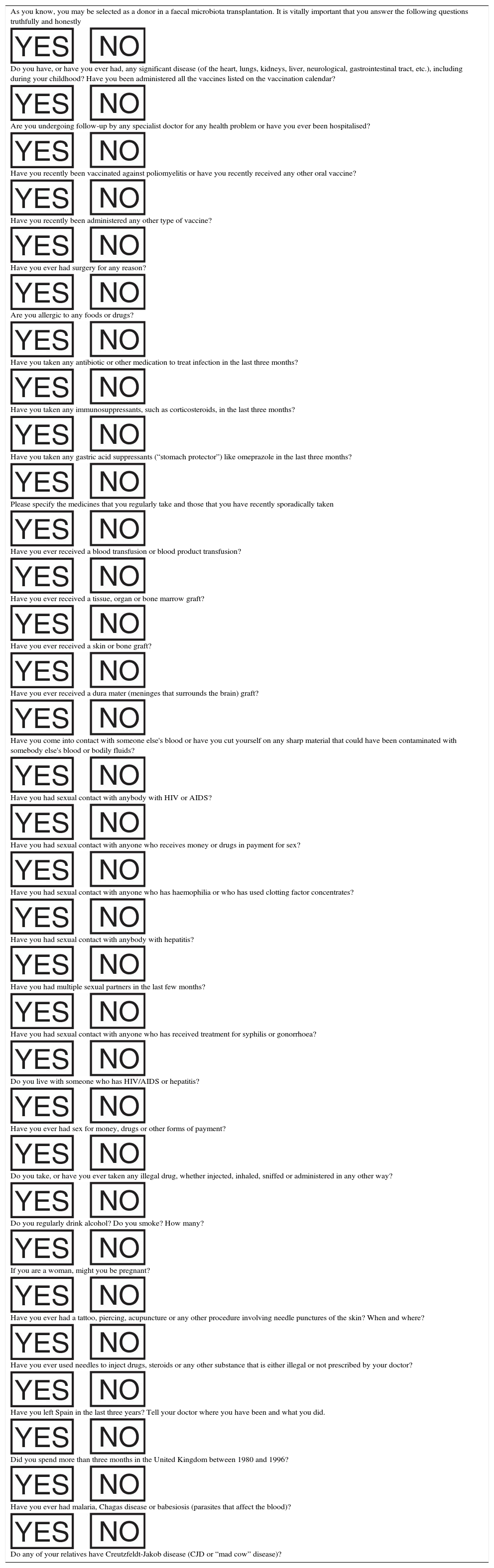

Donor screening questionnaire.

| As you know, you may be selected as a donor in a faecal microbiota transplantation. It is vitally important that you answer the following questions truthfully and honestly |

| Do you have, or have you ever had, any significant disease (of the heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, neurological, gastrointestinal tract, etc.), including during your childhood? Have you been administered all the vaccines listed on the vaccination calendar? |

| Are you undergoing follow-up by any specialist doctor for any health problem or have you ever been hospitalised? |

| Have you recently been vaccinated against poliomyelitis or have you recently received any other oral vaccine? |

| Have you recently been administered any other type of vaccine? |

| Have you ever had surgery for any reason? |

| Are you allergic to any foods or drugs? |

| Have you taken any antibiotic or other medication to treat infection in the last three months? |

| Have you taken any immunosuppressants, such as corticosteroids, in the last three months? |

| Have you taken any gastric acid suppressants (“stomach protector”) like omeprazole in the last three months? |

| Please specify the medicines that you regularly take and those that you have recently sporadically taken |

| Have you ever received a blood transfusion or blood product transfusion? |

| Have you ever received a tissue, organ or bone marrow graft? |

| Have you ever received a skin or bone graft? |

| Have you ever received a dura mater (meninges that surrounds the brain) graft? |

| Have you come into contact with someone else's blood or have you cut yourself on any sharp material that could have been contaminated with somebody else's blood or bodily fluids? |

| Have you had sexual contact with anybody with HIV or AIDS? |

| Have you had sexual contact with anyone who receives money or drugs in payment for sex? |

| Have you had sexual contact with anyone who has haemophilia or who has used clotting factor concentrates? |

| Have you had sexual contact with anybody with hepatitis? |

| Have you had multiple sexual partners in the last few months? |

| Have you had sexual contact with anyone who has received treatment for syphilis or gonorrhoea? |

| Do you live with someone who has HIV/AIDS or hepatitis? |

| Have you ever had sex for money, drugs or other forms of payment? |

| Do you take, or have you ever taken any illegal drug, whether injected, inhaled, sniffed or administered in any other way? |

| Do you regularly drink alcohol? Do you smoke? How many? |

| If you are a woman, might you be pregnant? |

| Have you ever had a tattoo, piercing, acupuncture or any other procedure involving needle punctures of the skin? When and where? |

| Have you ever used needles to inject drugs, steroids or any other substance that is either illegal or not prescribed by your doctor? |

| Have you left Spain in the last three years? Tell your doctor where you have been and what you did. |

| Did you spend more than three months in the United Kingdom between 1980 and 1996? |

| Have you ever had malaria, Chagas disease or babesiosis (parasites that affect the blood)? |

| Do any of your relatives have Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD or “mad cow” disease)? |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

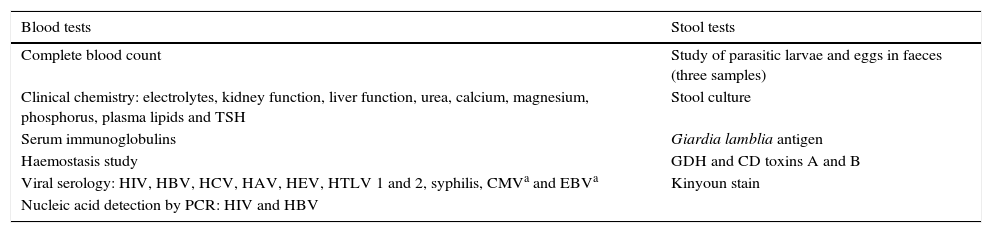

Tests undertaken by donors.

| Blood tests | Stool tests |

|---|---|

| Complete blood count | Study of parasitic larvae and eggs in faeces (three samples) |

| Clinical chemistry: electrolytes, kidney function, liver function, urea, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, plasma lipids and TSH | Stool culture |

| Serum immunoglobulins | Giardia lamblia antigen |

| Haemostasis study | GDH and CD toxins A and B |

| Viral serology: HIV, HBV, HCV, HAV, HEV, HTLV 1 and 2, syphilis, CMVa and EBVa | Kinyoun stain |

| Nucleic acid detection by PCR: HIV and HBV |

CD: Clostridium difficile; CMV: cytomegalovirus; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; GDH: glutamate dehydrogenase; HAV: hepatitis A virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HEV: hepatitis E virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HTLV: human T-cell lymphotropic virus; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone.

The processing and analysis of the donor's and recipient's faeces is performed by the Department of Microbiology. The samples must only be handled in the laboratory under a laminar flow hood by staff wearing personal protective equipment (biosafety level 2), including an apron, gloves, mask and goggles. To obtain the microbiota solution, 100g of faecal matter are solubilised with 500ml of physiological saline solution (NaCl 0.9%) using a beater for FMT use only. Once the homogeneous solution has been obtained, it is centrifuged to deposit the fibre and insoluble parts, and the supernatant is then collected in ten 50-ml narrow syringes suitable for colonoscopy. The sampling process must be coordinated with the Endoscopy Unit to ensure that preparation begins about 30min before the colonoscopy and to prevent the sample from being out of the fridge for too long, as samples are kept at room temperature once prepared to prevent hypothermia during instillation.

Endoscopic procedureColonoscopy preparation involves 4l of polyethylene glycol lavage solution administered in multiple fractions, commencing the evening prior to the FMT. In patients in poor general health, or with significant comorbidity, smaller volumes of preparation solutions may be taken or the patient may be admitted for the preparation phase.

During the colonoscopy, all personnel involved are equipped with personal protective equipment. As a general rule, the procedure is performed under sedation (either by an anaesthetist or an endoscopist, depending on the patient's characteristics). The colonoscopy is initially performed with minimal insufflation, obtaining two biopsies of the caecum for microbiological study. Once the caecum has been reached, FMT instillation takes place through the colonoscope working channel as follows: 350ml of faecal solution in the ascending colon, 100ml in the transverse colon and the remaining 50ml in the descending colon. Aspiration must be avoided during endoscope extraction to prevent removing the transplanted material.

Once the procedure has been completed and the patient has recovered from the effects of sedation, 2mg of oral loperamide are administered and the patient is instructed to try to retain the administered solution for as long as possible (ideally for at least 4–6h). Bed rest is recommended for 24h and a diet adjusted to the patient's clinical situation, with no other restrictions, can be resumed 6h after the procedure.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed with the Stata software version 14.0 (StataCorp®, Texas, USA). The quantitative data are presented using the median as measure of central tendency and the range as measure of dispersion due to the marked asymmetry of the distributions. The qualitative data are shown as absolute and relative frequencies. Clinical success was defined as a dichotomous variable and its 95% confidence interval was estimated by the Wilson method. Due to the study design, no significance testing or estimation of the sample size were conducted.

Ethical aspectsGiven the lack of national and European regulation for this procedure, and having consulted the Clinical Trials Committee and the local Healthcare Ethics Committee, as well as the Spanish National Transplant Organisation, the programme was launched with specific authorisation from the centre's management. The study was approved by the Hospital Ramón y Cajal Independent Ethics Committee (IEC). All donors and recipients signed the informed consent to conduct the procedure.

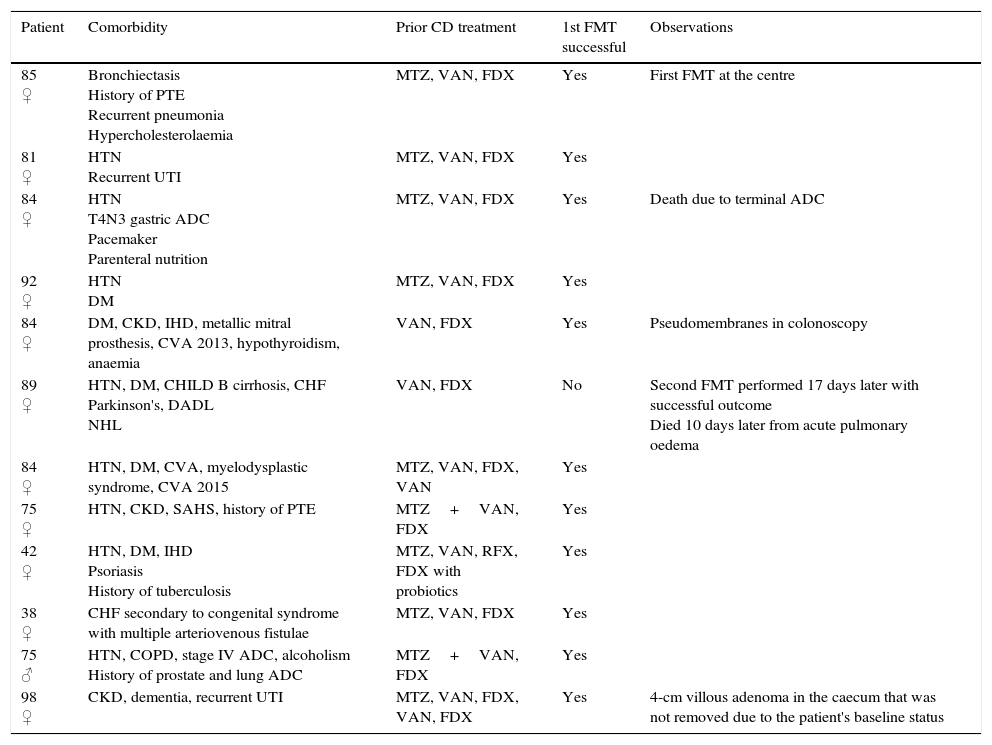

ResultsA total of 16 donors were studied, with a median of one donor (range: 0–2) per recipient; in 11 cases (84.6%), the donor was related to the recipient. A total of 13 FMTs were performed on 12 patients, with a median age of 84.6 years (range: 38.2–98.2), 11 (91.7%) of whom were women (Table 5). One Hindu patient rejected FMT on religious grounds. Four patients did not belong to our institution and were referred to our centre for the procedure. The indication in all cases was multiple recurrence of CDI. No patient received immunosuppressants. All patients had previously received fidaxomicin. The median number of episodes prior to FMT was three (range: 2–6), with a median of 68.5 days (range: 24–306) between onset of the first CDI episode and the first FMT. Twenty-four hours prior to the FMT, the median number of bowel movements per day was 3.5 (range: 2–12). Two patients presented with bloody stools, seven with abdominal pain and two with nausea. All procedures involved colonoscopy, with caecal intubation in nine patients (69.2%), the proximal ascending colon reached in three patients and the sigmoid in just one patient. 500ml of filtered faecal solution were used in all cases, instilling 350ml in the caecum and ascending colon, 100ml in the transverse colon and 50ml in the descending colon in 12 FMTs and injecting all the solution into the sigmoid and rectum in one case. Sedation was administered by the endoscopist in five FMTs, by the anaesthetist in seven cases, and one patient was not sedated. In terms of preparation, eleven patients received 4l of polyethylene glycol lavage solution and one patient received just 2l of polyethylene glycol owing to an underlying comorbidity (chronic heart failure and liver cirrhosis). Incidental findings arising during the endoscopy were: uncomplicated diverticulosis in three patients (25%); erythema and oedema in two patients (16.6%) pseudomembranes in one case, one 4-cm villous adenoma in the caecum and one 1-cm pedunculated polyp in the rectum.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient | Comorbidity | Prior CD treatment | 1st FMT successful | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85 ♀ | Bronchiectasis History of PTE Recurrent pneumonia Hypercholesterolaemia | MTZ, VAN, FDX | Yes | First FMT at the centre |

| 81 ♀ | HTN Recurrent UTI | MTZ, VAN, FDX | Yes | |

| 84 ♀ | HTN T4N3 gastric ADC Pacemaker Parenteral nutrition | MTZ, VAN, FDX | Yes | Death due to terminal ADC |

| 92 ♀ | HTN DM | MTZ, VAN, FDX | Yes | |

| 84 ♀ | DM, CKD, IHD, metallic mitral prosthesis, CVA 2013, hypothyroidism, anaemia | VAN, FDX | Yes | Pseudomembranes in colonoscopy |

| 89 ♀ | HTN, DM, CHILD B cirrhosis, CHF Parkinson's, DADL NHL | VAN, FDX | No | Second FMT performed 17 days later with successful outcome Died 10 days later from acute pulmonary oedema |

| 84 ♀ | HTN, DM, CVA, myelodysplastic syndrome, CVA 2015 | MTZ, VAN, FDX, VAN | Yes | |

| 75 ♀ | HTN, CKD, SAHS, history of PTE | MTZ+VAN, FDX | Yes | |

| 42 ♀ | HTN, DM, IHD Psoriasis History of tuberculosis | MTZ, VAN, RFX, FDX with probiotics | Yes | |

| 38 ♀ | CHF secondary to congenital syndrome with multiple arteriovenous fistulae | MTZ, VAN, FDX | Yes | |

| 75 ♂ | HTN, COPD, stage IV ADC, alcoholism History of prostate and lung ADC | MTZ+VAN, FDX | Yes | |

| 98 ♀ | CKD, dementia, recurrent UTI | MTZ, VAN, FDX, VAN, FDX | Yes | 4-cm villous adenoma in the caecum that was not removed due to the patient's baseline status |

ADC: adenocarcinoma; CD: Clostridium difficile; CHF: congestive heart failure; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; DADL: dependent in activities of daily living; DM: diabetes mellitus; FDX: fidaxomicin; FMT: faecal microbiota transplantation; HTN: hypertension; IHD: ischaemic heart disease; MTZ: metronidazole; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism; RFX: rifaximin; SAHS: sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome; UTI: urinary tract infection; VAN: vancomycin.

Twelve out of the thirteen FMT procedures (92.3%) were performed in the hospital, with a median post-FMT hospitalisation of 2.5 days (range: 0–8). No patient required intensive care. 48h after the FMT, the symptoms of all patients had abated with a median of one daily bowel movement (range: 0–2). The effectiveness of one FMT session was 91.7% (11/12; 95% CI: 64.6–98.5%). In the patient who did not respond to treatment and in whom the colonoscopy only reached the sigmoid, a second FMT was performed with faeces from the same donor 17 days later, achieving complete abatement of symptoms. No side effects to the endoscopic procedure or to the FMT were reported after a median follow-up of 6.5 months (range: 1–16 months). Two patients died during follow-up for causes unrelated to the FMT (terminal gastric adenocarcinoma and acute pulmonary oedema). One patient from another autonomous community experienced mild diarrhoea after taking antibiotics three months after the FMT, which was treated by her doctors with vancomycin. She experienced no further diarrhoea during subsequent follow-up.

DiscussionRecent studies have shown that recurrent CDI is associated with high costs, hospital readmissions and even increased mortality.8,9 Although fidaxomicin is superior to classic treatments, some patients still experience recurrences, especially when administered to patients with multiple recurrences of CDI.10 Despite the fact that FMT is an excellent alternative in this scenario, no data supporting its efficacy have been published to date in Spain.

The key to FMT is the microbiota donor, but the most efficient screening method and the closeness of the relationship with the recipient are still much disputed. In our protocol, the inclusion and exclusion criteria are based primarily on the review conducted by Bakken et al. (Tables 2 and 3). Although quite restrictive, we believe that this is justified due to the risk of pathogen transmission and the limited availability of donors.7 In our study, 11 of the 13 FMTs were conducted with related donors. The advantage of this approach is greater accessibility and shared environmental risk factors, which could minimise the risk of infection transmission.7 However, a meta-analysis of 273 patients found no statistically significant differences in the rate of clinical resolution between anonymous donors and donors related to the recipient.11

Although fresh faeces were used in all our patients, consistent with the method of choice stipulated in the protocol, it has been shown that faeces may be frozen at −80°C for up to six months without loss of viability.12 In this regard, Lee et al. recently published a clinical trial with 219 patients that found that outcomes with frozen faecal material is not inferior to fresh samples.13 The use of frozen faeces is less expensive as multiple transplants may be performed from a single donor. It also makes FMT viable for patients without family or without accessible or appropriate donors. In terms of the volume of faeces, 500ml of microbiota solution were administered to all patients. This decision was based on the systematic review conducted by Gough et al., where the CDI resolution rate was directly and proportionally associated with the volume infused (97% with >500ml versus 80% if <200ml).14 This review also found that recurrence was four times more likely when the weight of the faeces was <50g, which is why 100g were used in our protocol.14

Enemas were initially administered until the duodenal route was introduced in 1991 and the colonoscopy in 2000, which is currently the most widely used approach.6,15,16 Despite the fact that the optimal route has still not been definitively established as no comparative study has been specifically designed for this purpose, we believe that colonoscopy is the best option as it has shown greater therapeutic success versus the upper gastrointestinal route in numerous systematic reviews (89–92% versus 76–82%), as well as greater theoretical patient acceptance.11,14 Moreover, unlike enemas which only reach the splenic flexure and could theoretically be less effective, with colonoscopy, the solution can be instilled throughout the entire colon and even in the terminal ileum. Colonoscopy also allows the seriousness of the disease to be evaluated through inspection of the colonic mucosa. Histological samples may also be obtained and the presence of any comorbidity assessed. In our series, abnormal mucosa was found in three patients (23%), in whom findings consistent with CDI were seen. Two preneoplastic lesions were also identified, similar to the findings of previous series.17,18

It is important to emphasise that precautions should be taken during the colonoscopy, such as minimal insufflation and not forcing the colonoscope through difficult angles, which explains the low rate of caecal intubation in our series. Regarding colonoscopy preparation, the use of lavage solutions seems to reduce the density of both CD bacteria and their spores, which is why experts recommend their administration on the day preceding the FMT, irrespective of the route of administration.19

Recipients of FMT for CDI tend to be frail, elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, which is true of most of the patients treated at our centre (Table 5).16,20 Although FMTs were not performed on immunosuppressed patients as this is an exclusion criteria of the initial protocol, it is likely that this criterion will have to be amended as various working groups have reported favourable outcomes with no increased risk of infection.21,22

A wide variety of definitions of recurrence and infection cure can be found in the literature, which partly explains the variable success rates published. Most studies base the definition of cure on purely clinical criteria (complete abatement of diarrhoea), with timescales ranging from one week to six months.16 This study defined cure as the lack of diarrhoea in the first eight weeks after the FMT, consistent with the recommendations of the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID).2,6 The clinical success rate with a single procedure was 91.7% (95% CI: 64.6–98.5%), with a second FMT required in one case due to infection recurrence after the first FMT. These positive outcomes are consistent with those obtained in uncontrolled clinical trials and studies.16,18,23

There is currently a lack of sufficient evidence to determine the necessary number or frequency of infusions. In the 2016 systematic review by Chapman et al., the number of FMTs per patient ranged from one to 10, with infection recurrence identified as the most common reason for repeating the procedure.16 In another systematic review of 801 cases of FMT with various indications, 83.3% of patients received one single instillation.15

In our study, just one outpatient procedure was performed due to the frailty of the patients treated. In the future, if the indications for FMT are broadened or if its use in CDI is prioritised, a significant number of procedures can be expected to be performed at outpatient clinics.

In general, the adverse effects of FMT are rare, mild and transitory. Publication bias, the retrospective nature of many series and the lack of long-term data mean that available information should be interpreted with caution. There is a potential risk of pathogen transmission despite strict donor screening, with two cases of post-FMT norovirus-induced acute gastroenteritis reported in the literature.24 In the first days after the procedure, the most common adverse effects are abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, a bloated feeling, diarrhoea and flatulence. Other reported side effects include constipation, vomiting, pruritus, paraesthesia, catarrh, headache, appearance of blisters on the tongue and transitory fever.25 In our series, no short- or medium-term adverse effects were recorded, although, owing to the retrospective nature of the study, minor symptoms (nausea, abdominal discomfort, etc.) may not have been reported. Two patients died during follow-up, one due to terminal gastric adenocarcinoma and the other due to acute pulmonary oedema 10 days after the second FMT. Although a possible link between colonoscopy preparation and the second patient death referred to above could be hypothesised, we consider this to be very unlikely as the patient was discharged five days after the colonoscopy with stable cardiorespiratory status, a lower volume of lavage solution was administered and the patient's medical history refers to multiple admissions due to decompensated chronic heart failure (Table 5). To date, after more than 1000 published cases, no death with a direct causal link to FMT has been reported.

From a financial perspective, it should be noted that the introduction of FMT at the centre did not involve any additional costs for the healthcare system as human resources and materials that were already available and accessible to any tertiary hospital were used for routine care. In fact, numerous studies have been published that support its efficiency.26,27

The main limitations of this study are its small sample size, the heterogeneity of the subjects included and the retrospective collection of information. Nevertheless, we believe that it is a valid test of the applicability and effectiveness of FMT in Spain.

The principal challenges FMT will face in the future are the standardisation and simplification of its steps, ascertaining the possibility of isolating microbiota subpopulations that offer real therapeutic power, improving our understanding of its long-term effects, understanding its effectiveness in refractory CDI and defining its true utility in other diseases. Clinical trials in the fields of inflammatory bowel disease, hepatic encephalopathy, primary sclerosing cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, metabolic syndrome, eradication of multidrug-resistant bacteria in rectal carriers, HIV and epilepsy are currently ongoing.28,29

ConclusionsThe results obtained at our centre offer further evidence of the effectiveness and safety of FMT by colonoscopy in recurrent CDI. It is a simple procedure backed by scientific evidence, whose conduct in our setting is feasible with a multidisciplinary team. Beyond its potential value as a research tool, its use meets a current and growing care need. As such, we believe that its implementation should be promoted at other tertiary centres to facilitate its accessibility, centralise tasks and encourage the founding of regional microbiota banks in order to optimise the procedure.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: López-Sanromán A, Rodríguez de Santiago E, Cobo Reinoso J, del Campo Moreno R, Foruny Olcina JR, García Fernández S, et al. Resultados de la implementación de un programa multidisciplinar de trasplante de microbiota faecal por colonoscopia para el tratamiento de la infección recurrente por Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:605–614.