Haemorrhagic complications of acute pancreatitis (AP) are uncommon and are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Likewise, the imbalance of the clotting system in severe AP favours the onset of thrombotic events at the splanchnic level. We present the case of a complication that has not been described to date, which reflects this phenomenon and the complexity of managing these patients.

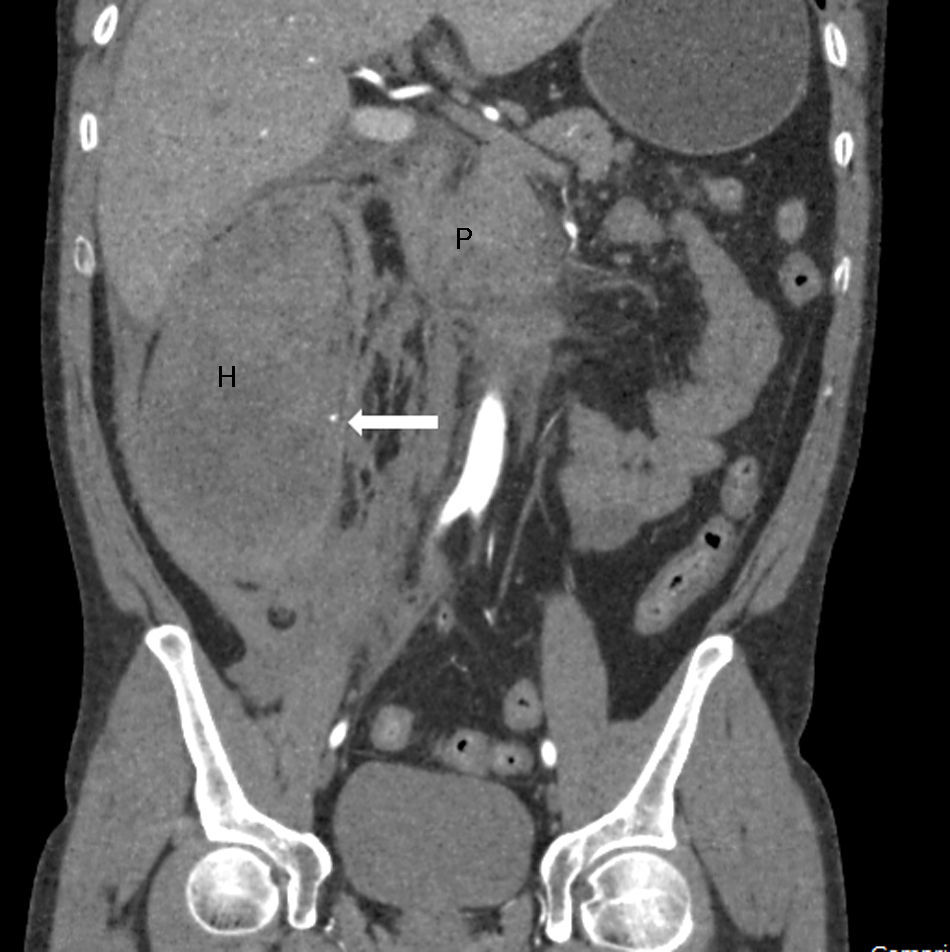

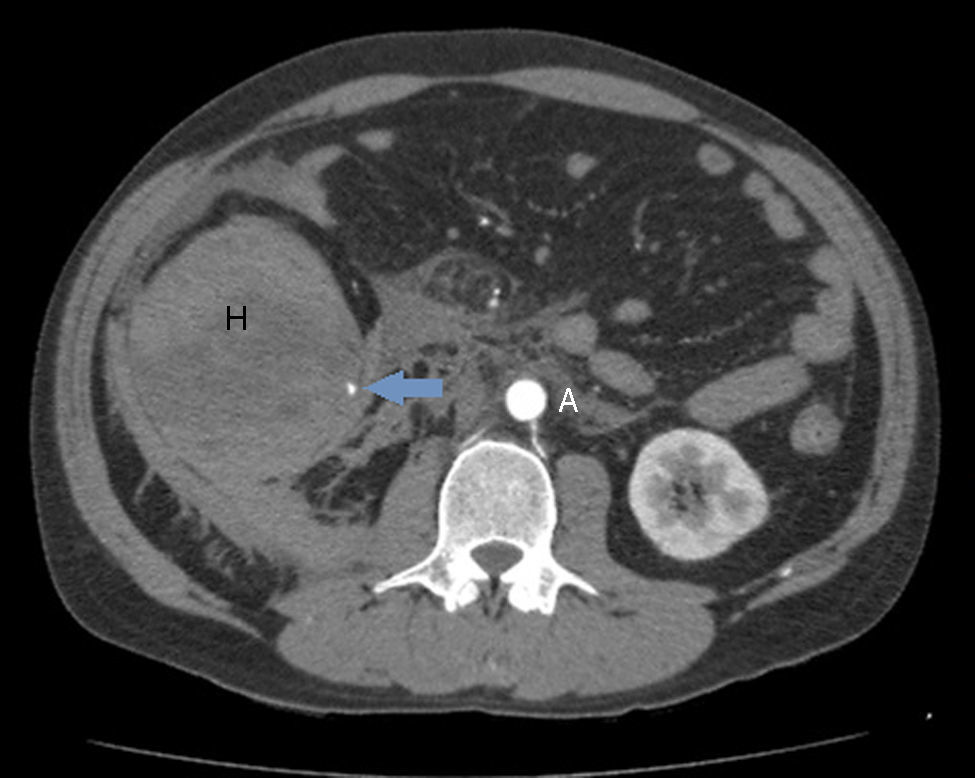

A 42-year-old male smoker and drinker of 120g of alcohol/day, who was admitted to our department after a 48h period of continuous epigastric abdominal pain, compatible with the diagnosis of AP. In the blood tests performed on admission, noteworthy findings included a total bilirubin of 2.96mg/dl (normal: <1.2mg/dl), GGT 500U/l (normal: 7–30U/l), LDH 346U/l (normal: 140–240U/l), amylase 144U/l (normal: 42–141U/l), lipase 355IU/l (normal: 42–111U/l), CRP 147mg/l (normal: <5mg/l) and white blood cells of 21,700/μl (normal: <10,500/μl). The patient's transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, urea and haematocrit were normal. The abdominal ultrasound on admission did not show any relevant findings. In light of persistent pain on the third day and an increase in CRP to 234mg/dl, an abdominal CT scan was performed in which pancreatic head necrosis (25–30% of the parenchyma) was observed, along with thrombosis of 50% of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). We decided to initiate anticoagulant therapy with low molecular weight heparin at doses of 1mg/kg/12h. The patient evolved favourably until, on the seventh day, he suddenly presented severe pain in the lower hemiabdomen, a deterioration in his general condition and anaemia with 5g/dl haemoglobin. During the examination, the sudden appearance of a mass on the right flank was notable, measuring 8cm in diameter. An urgent CT angiography was performed, which revealed a haematoma of 8cm×15cm×9cm in the wall of the right colon, which stenosed its lumen, as well as two bleeding points dependent on the right colic artery (Figs. 1 and 2). The anticoagulation was suspended indefinitely and superselective arteriography was performed, proceeding to the embolization of three branches depending on the right colic artery, without achieving control of the bleeding. The patient underwent an urgent intervention, targeting a perforation of the wall of the caecum. A right hemicolectomy was performed with a terminal ileostomy, together with placement of a drain in the necrosis of the pancreatic head. The anatomopathological study of the colon revealed the presence of transmural ischaemic lesions, caecal perforation covered with fibrinopurulent material, and the presence of an organized 10cm×16cm haematoma that penetrated the outer layer of the muscular wall of the colon and entered the mesocolon. Recovery during the postoperative period was slow but favourable and, at present, two years post-admission, the patient is asymptomatic with a permeable splenoportal axis.

The haemorrhagic complications of AP are associated with severe cases with parenchymal necrosis, with variable mortality depending on the series, ranging between 34 and 52%.1 The origin of the haemorrhage is usually some arterial or venous vessel of the peripancreatic region, with the most frequent cause being the rupture of a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm.2 It less commonly affects abdominal vessels beyond the inflammatory focus and, in our search, we found no cases in which bleeding at the level of a right colic artery branch is described. The pathophysiological mechanism of haemorrhage is multifactorial and has not been fully explained; probably in the patient in question and when it appears in the initial phases of AP, the aetiopathogenic factor of greatest weight is the erosion of the vascular wall by proteolytic and lipolytic agents stemming from the process of pancreatic autodigestion.2 In the context of severe AP, the sudden appearance of abdominal pain, distension, low output symptoms and anaemia, with or without externalized digestive bleeding, are highly suggestive of a haemorrhagic complication and constitute the most frequent clinical presentation; however, haemorrhages may also manifest in a subacute manner.1,2

Despite the absence of randomized studies and the risk of publication bias, numerous cohorts of tertiary-level hospitals endorse the efficacy of interventional radiology in locating and controlling arterial bleeding in this setting.3,4 The initial therapeutic success may reach 75% at experienced centres, although rebleeding is a common occurrence.3 It should be attempted as soon as possible if the patient's condition and the hospital facilities allow it. When this procedure fails, surgical intervention should not be delayed as conservative treatment offers dismal expectations with a very high mortality rate (54–89%).2

In the case presented, the spontaneous caecal perforation, which is a very uncommon occurrence but is described with AP,5 was probably of an ischaemic origin. We believe that the main causal factors behind the perforation were the mass effect that the haematoma itself could exert on the colonic microcirculation, the reduction of the arterial inflow due to the lack of integrity of the right colic artery and, to a lesser extent, an insufficient venous return due to partial SMV thrombosis.

Moreover, we hypothesize that the systemic inflammatory response and systemic release of procoagulant factors are responsible for the higher incidence of thrombotic events. Venous thrombosis of a splanchnic system branch occurs in approximately 1–24% of cases and is more frequent in severe AP.6 The prevalence of SMV thrombosis is lower than in the splenoportal axis and, when it appears, it does not usually lead to additional complications, regardless of whether or not the patient receives anticoagulation.6,7 However, cases of thrombosis extension and secondary intestinal ischaemia have also been reported.8 Anticoagulation in this context is a highly controversial issue due to the lack of clinical trials. Most of the published cohorts are retrospective, offer contradictory data, and have focused on the management of splenic vein or portal vein thrombosis.6,7 In the patient in question, anticoagulant treatment probably accentuated the severity of the haemorrhage and made it difficult to control.

FundingThe authors declare that they have not received any kind of public or private monetary compensation for the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez de Santiago E, Téllez Villajos L, Peñas García B, Foruny Olcina JR, García García de Paredes A, Ferre Aracil C, et al. Pancreatitis aguda necrótica y aparición súbita de una masa abdominal: una complicación infrecuente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:292–293.