Individuals with psychotic disorders may display over the illness course a wide range of core deficits in clinical and cognitive domains, including social cognition (SC). One of the main domains of SC is emotional processing, a key component of emotional intelligence (EI). However, the extent to which EI, as self-perceived or performance-based, is related to psychopathological domains has been scarcely studied. This study aimed to examine the relationships between self-reported EI and performance-based EI with psychopathological and insight dimensions as well as to explore the correspondence between both types of EI assessments.

MethodsSeventy patients with psychotic disorders who were consecutively admitted to a psychiatric hospitalization unit were included. Psychotic, affective, and insight dimensions, as well as EI, were evaluated once psychopathological stability had been achieved.

ResultsManic symptoms were associated with greater emotional clarity (r = 0.25, p < 0.05) and regulation (r = 0.30, p < 0.05), whereas depressive symptoms were associated with lower emotional regulation (r=-0.25, p < 0.05). No significant relationships were found between the EI measures and psychotic dimensions. Lack of feeling sick and lack of insight were related to worse performance-based EI (emotional management, r=-0.29 and r=-0.25, p < 0.05) and self-reported EI (emotional attention, r=-0.24, p < 0.05 and r=-0.31, p < 0.01), and the former was also related to better emotional regulation (r = 0.26, p < 0.05).

ConclusionThe discrepancy between self-reported and performance-based EI regarding their associations with psychopathological domains might be due to the different sources of assessment but may also add evidence to the need to integrate patient-reported outcome measures in the assessment of social cognition.

Social cognition (SC) encompasses the mental processes and operations that underpin social interaction. These mechanisms allow us to perceive, interpret, and generate responses to social information received from the surrounding environment, such as the intentions, attitudes, and behaviours of others.1,2 Therefore, SC plays a fundamental role in the formation of meaningful and effective interpersonal relationships in society,3 and SC deficits are considered to increase the vulnerability to the development of schizophrenia,4 as well as cognitive deficits.5 In fact, a bidirectional relationship between SC, neurocognition and cognitive reserve has been suggested, implying that deficits in these areas are present since early phases of development.6

SC is a multidimensional construct with deficits present in patients with schizophrenia from the first episode of psychosis (FEP), including social exclusion, impaired interpersonal functioning, and cognitive deficits that affect their ability to interact effectively in social contexts.7–9 Given the importance of this construct, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) met in 2006 to create a consensus on the definition of the social cognition construct and areas of interest within psychotic disorders for future lines of research.10 Psychotic disorders include severe mental disorders that present with psychotic symptoms (positive, negative, and disorganised), with schizophrenia being the most severe psychotic disorder. Research on SC in schizophrenia has focused on the following subdimensions: social perception, theory of mind, attributional style, and emotion processing.2,11

Over the past decade, research on SC in schizophrenia has experienced significant renewed interest due to its impact on the daily functioning and social behaviour of these patients.2,12–14 In fact, FEP patients show less initiative and motivation toward social activities and are often more socially isolated than before the illness.15,16 Furthermore, poorer social performance is associated with increased relapse, a worsening disease course, increased disability, and specific neurocognitive deficits.17–19

The most studied subdimension of SC in patients with schizophrenia is emotional processing, since it was selected as one of the main domains to be included in the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB).10,20 Emotional processing is a key process of Emotional Intelligence (EI) and is defined as “the subset of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate between them, and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions”.21

EI can be measured using both performance-based and self-reported methods. Performance-based measures of EI refer to the structured and objective measurement of emotional competencies and skills using quantified methods and scales in line with the Ability Model of EI proposed by Salovey and Mayer.21 For this purpose, there are tests such as the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT),22 which evaluates the performance of people in identifying and understanding their own emotions and those of others. Self-reported measures of EI refer to the meta-experience of one's own emotions and beliefs about one's own emotional abilities and skills, which can be influenced by personal and contextual factors. These type of measures are aligned with the Trait Model of EI.23 One of the most widely used instruments for this purpose is the Trait Meta Mood Scale (TMMS).24

People with schizophrenia show worse EI compared with non-clinical groups or those with other pathologies, such as bipolar disorder.25,26 In their systematic review, Lawlor et al.27 reported that people with psychotic disorders showed greater difficulty in different aspects of emotion regulation, the most notable being emotional clarity. However, most studies have assessed EI through performance on tests such as the MSCEIT,22 a performance-based measure, regardless of how they recognise their own emotions.6 Research such as that conducted by Benito-Ruiz et al.28 highlights the importance of assessing SC through more ecologically valid contexts based on real interactions. Likewise, the inclusion of these dimensions in the functional assessment of patients with schizophrenia in the early stages of the disorder will enable a comprehensive understanding of psychosocial functioning and may increase the effectiveness of interventions.29 In recent years, network analysis has become popular in research in psychotic disorders, since it represents a powerful method of investigating the relationships among clinical variables accounting for the effect of the rest of variables.30 Network analyses have been mainly used in psychotic disorders to study cognitive and psychopathological variables.31–33 Social cognition, and specifically emotion processing, has been related to negative symptoms and social functioning in FEP patients using network analyses.33,34 Thus, network analysis may provide a complimentary perspective on the interactions between EI measures and psychopathological and insight measures.

Research concerning the relationship between EI and the psychopathological dimensions of psychotic disorders is scarce. One of the most characteristic symptoms of psychotic disorders is a lack of awareness or insight into the disease.35,36 Pijnenborg et al.37 suggest that the ability to regulate emotions contributes to adequate clinical insight. Subjects who regulate their emotional states are likely to adapt better to the impaired functioning and negative stigma associated with schizophrenia, and thus, be more willing to acknowledge the presence of a mental disorder. The psychological denial model postulates that this stigma causes high levels of distress; therefore, denial is used as an emotional coping strategy and, consequently, leads to poor insight.38

Our aim was to compare self-reported and performance-based measures of EI and examine their respective associations with the psychopathological and insight dimensions in patients with psychotic disorders. We also aimed to study the concordance between the two types of EI assessment. We hypothesised that a lack of insight would be more related to self-reported than performance-based EI measures, and that psychotic and affective symptoms would be partially associated with both EI measures.

MethodsParticipantsThe sample consisted of a cohort of 70 patients consecutively admitted to the Hospital Universitario de Navarra (Spain) because of a psychotic episode. They were diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; APA, 2013) criteria. The diagnoses were schizophrenia (n = 28, 40 %), schizoaffective disorder (n = 9, 12.9 %), bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms (n = 23, 32.9 %), and other psychoses (n = 10, 14.2 %) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

SES: Socioeconomic status (Adapted from Hollingshead Reitan Scale); IQ: Intelligence Quotient; CASH: Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History; AMDP: Manual for Assessment and Documentation in Psychopathology; TMMS: Trait Meta-Mood Scale; TMMS-A: Emotional Attention; TMMS-C: Emotional Clarity; TMMS-R: Emotional Regulation.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: agreement to participate in the research and sign the informed consent form, to be between 18–50 years of age, to be fluent in Spanish, an intelligence quotient (IQ) ≥ 70, absence of neurological or serious medical disease, and mental disorder not explained by organic disease or by the consumption of toxic substances. Exclusion criteria included any history of substance dependence within the past five years, head injury with loss of consciousness, seizures, and central nervous system infections.

The Ethical Committee of Navarra (Spain) approved the study protocol (Project 84/11), and all patients provided written informed consent.

MeasuresClinical assessmentsThe patients were evaluated using the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH),39 a semi-structured interview that allows for the assessment of the following psychopathological dimensions at discharge made up of the average of global ratings of their item components: positive dimension (delusions and hallucinations), negative (affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia), disorganization (formal thought disorder, bizarre behaviour, inappropriate affect, and inattention), mania (mania items), and depression (depression items).

The assessment of insight was carried out using three items from the Manual for Assessment and Documentation in Psychopathology (AMDP System).40,41 It comprises three items for evaluating insight (not feeling sick, lack of insight, and uncooperativeness or refusal of treatment), which mirrors the three insight dimensions included in David's model.42

Emotion processing assessments: performance-based and self-reported EI measuresPerformance-based EI was assessed using the Managing Emotions branch of the MSCEIT scale43 included in the MCCB,20 due to its specific relevance in the assessment of emotional regulation, which is central to the objectives of this study. This branch is composed of two tasks: emotional management and emotional relationships, which assess emotional self-regulation and the ability to identify how others regulate their emotions. The scores obtained were normative values provided by the MCCB, with an average score of 100 and standard deviation of 15.

Self-reported EI was assessed using the TMMS-24 inventory.44 It is the first self-reported tool used to assess emotional intelligence from the Emotional Intelligence model of Salovey and Mayer.21,45 This scale is composed of 24 Likert-type response items and is designed to assess how individuals think about their moods and, therefore, how they acknowledge their intrapersonal emotional intelligence. The TMMS-24 is composed of three dimensions: 1) emotional attention (TMMS-A), the perceived ability to feel and express emotions appropriately; 2) emotional clarity (TMMS-C), the perceived understanding of one's own emotional states; and 3) emotional repair (TMMS-R), the perceived ability to correctly regulate one's own emotional states. The higher the score, the better was the perception of emotional intelligence. It should be noted that this scale does not provide a total score for the trait dimension but rather for the three subdimensions mentioned above. The scores on each scale ranged from 8 to 40. A high internal consistency has been demonstrated, and test-retest reliabilities with a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.90 in attention and clarity and 0.86 in repair.

ProcedureEmotional processing assessments were performed by a neuropsychologist (A.S.) who was blinded to patients’ psychopathological status. Two senior psychiatrists (M.J.C. and V.P.) collected the clinical data. Assessments were performed after psychopathological stabilization when patients were about to be discharged from the hospital. All assessments were conducted through face-to-face interviews. Self-reported assessments were administered using paper-pencil tests.

Data analysisWe first assessed the distribution of the data by performing Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests on the variables. As the variables were not normally distributed, we used Spearman's correlation coefficient, a nonparametric test, to explore the associations between EI scales regarding psychopathological dimensions and insight scores. Similarly, correlations between the MSCEIT and TMMS-24 scores were performed to check the congruence between the two scales. The Bonferroni correction adjustment was used to account for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 25.0).46

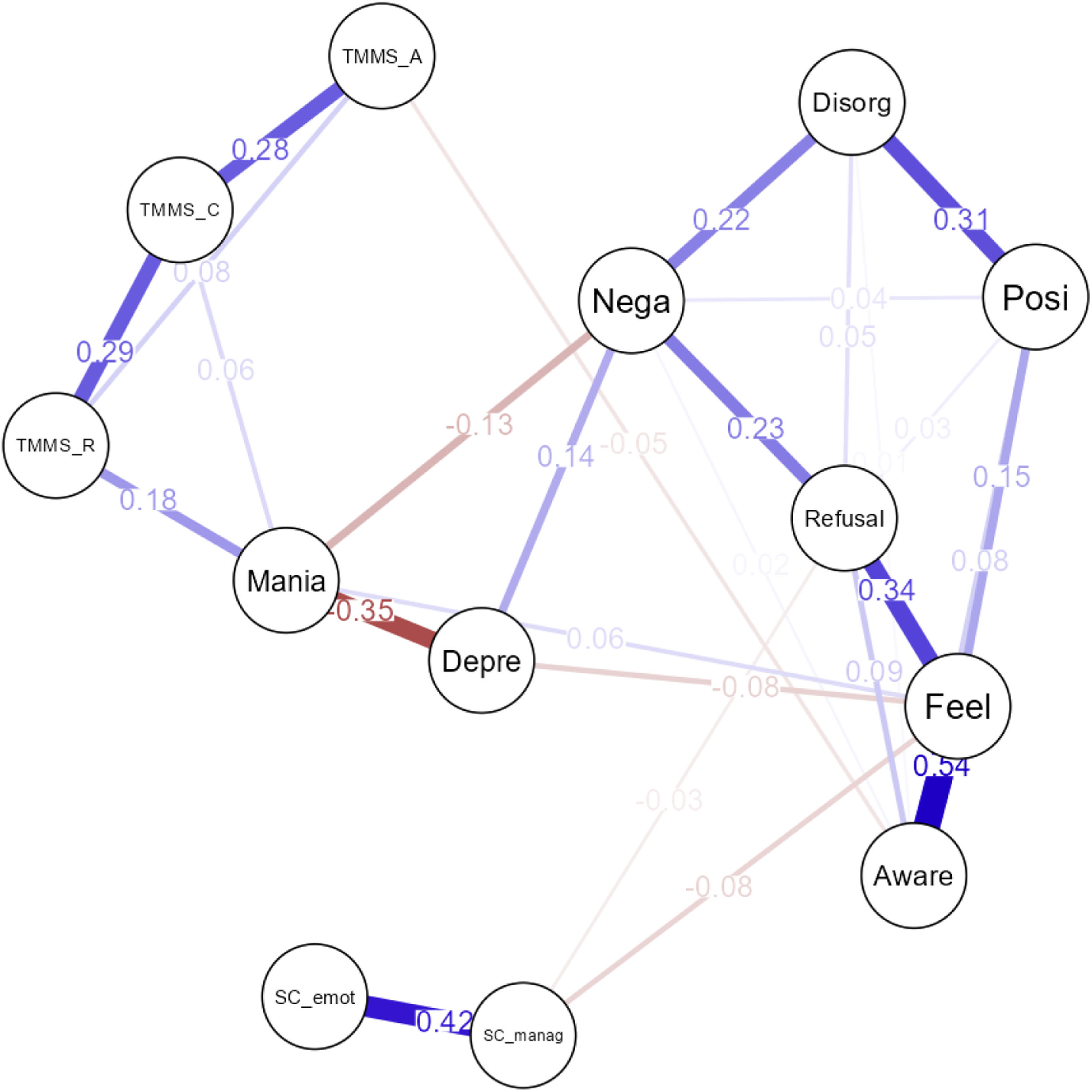

To gain a deeper understanding of the relationships among psychopathological dimensions, insight, and both performance-based and self-reported emotion-processing variables, a network analysis was conducted. We constructed a network using the graphical Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO)47 based on an extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC) model selection.48 The network comprised 13 evaluated variables. In this analysis, variables are represented as nodes, and the strength of their interconnections is estimated while controlling for the influence of other variables.30 The connections between nodes, referred to as edges, represent partial correlation coefficients that indicate the conditional independence of two variables after accounting for the effects of all other variables. The thickness of each edge corresponds to the strength of the association, with thicker edges indicating a stronger relationship.

Centrality indices were used to quantify the importance of each node within the network. We estimated two centrality measures: strength and expected influence. Strength is defined as the sum of the absolute values of the edges connected to a node. It is considered the main centrality parameter.49 Expected influence is a statistic similar to strength, but it accounts for both positive and negative associations between nodes.50 Items with expected influence values of ≥ 1 were considered as the most central ones. JASP software (Version 0.19.3.0)51 was used to conduct the network analysis.

Additionally, we conducted predictability tests using R Studio mgm package52 to estimate the practical relevance of the connections between nodes. These tests provide the amount of variance of a node that is explained by the nodes to which it is connected.

ResultsThe sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. There was a higher proportion of men (n = 45, 64.3 %) and most patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia (n = 28, 40 %) or bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms (n = 23, 32.9 %).

The mean scores on the TMMS-24 subscales indicated predominantly adequate emotional attention, clarity, and regulation according to normative data.44 However, scores ranged from 8 to 40, showing high variability in scores.

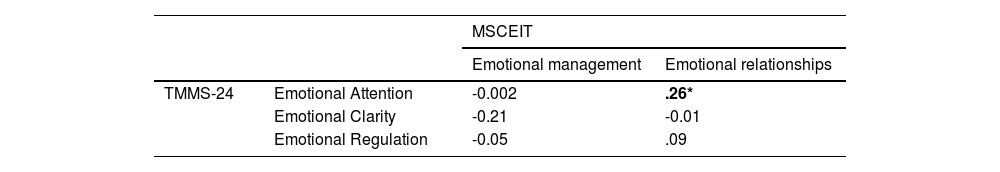

Relationship of the TMMS-24 and MSCEIT with psychopathological and insight dimensionsThe Spearman correlations between the performance-based and self-reported EI measures and psychopathological and insight dimensions are shown in Table 2. Regarding psychopathological dimensions, no significant correlations after Bonferroni correction were found between psychotic dimensions and performance-based or self-perceived EI scores. Patients with more manic symptoms showed a trend towards statistical significance with greater perceived emotional clarity and emotional regulation. There was a trend towards statistical significance of lower perceived emotional regulation in patients who manifested more depressive symptoms. Regarding insight dimensions, patients with lower awareness of insight had significantly lower levels of perceived emotional attention and a trend towards statistical significance with lower emotional management in the MSCEIT. Moreover, those with a lower feeling of being sick showed a trend towards statistical significance in exhibiting lower levels of emotional management in the MSCEIT and lower perceived emotional attention in the TMMS-24, but higher levels of emotional regulation (Table 2).

Spearman correlations between emotional intelligence, symptomatology and illness insight.

*p<.05; **p<.01.

Regarding the relationship between performance-based and self-reported EI measures, we found a significant correlation between emotional relationships and emotional attention (Table 3).

Network analysisThe structure of the network is shown in Fig. 1. The positive and negative edges are represented in blue and red, respectively. The regularized network retained 34.6 % of all the possible edges (27/78). In terms of strength and expected influence, the most significant node in the network was the lack of feeling sick, with values >1 in strength and expected influence (Fig. 2). The strongest association between nodes was observed between lack of feeling sick and lack of insight (0.54) and was also related to refusal of treatment (0.34) (see Fig. 1). Likewise, MSCEIT emotional management and emotional relationships nodes showed a strong connection between them (0.42) but were weakly connected to only one more node (lack of feeling sick, −0.08). Regarding the TMMS-24 dimensions, emotional clarity (TMMS-C) was associated with emotional perception (TMMS-A) and emotion regulation (TMMS-R) (0.28 and 0.29, respectively), and the latter was the only one that was connected with another node, specifically with manic symptomatology (0.18). Lack of feeling sick and lack of insight showed a connection with positive symptomatology (0.15 and 0.08) and refusal of treatment with negative symptomatology (0.23). Depression showed a negative association with mania (−0.35) and a lack of feeling sick (−0.08). Mania also showed an inverse association with negative symptoms (−0.13) and a weak positive connection with a lack of feeling sick (0.06). Finally, the association between positive/negative and disorganised symptomatology was also remarkable (0.31 and 0.22).

Network analysis of the 13 measures. Note: TMMS-A: emotional attention; TMMS-C: emotional clarity; TMMS-R: emotional regulation; SC manag, emotional management; SC emot, emotional relationships; Aware, lack of insight; Feel, lack of feeling sick; Refusal, refusal of treatment; Posi, positive symptoms; Nega, negative symptoms; Disorg, disorganized symptoms; Mania, manic symptoms; Depre, depressive symptoms.

Centrality indexes of the network. Note: TMMS-A: emotional attention; TMMS-C: emotional clarity; TMMS-R: emotional regulation; SC manag, emotional management; SC emot, emotional relationships; Aware, lack of insight; Feel, lack of feeling sick; Refusal, refusal of treatment; Posi, positive symptoms; Nega, negative symptoms; Disorg, disorganized symptoms; Mania, manic symptoms; Depre, depressive symptoms.

The predictability results showed that the lack of feeling sick and lack of insight were the nodes which were more explained by their connections. Specifically, 76.4 and 76.7 % of their variance, respectively (see Supplementary Material). In addition, emotional intelligence nodes, both self-reported and performance-based, showed high predictability, with 45.1 % and 63 % of the variance explained by the nodes connected to them.

DiscussionFive main findings were obtained in this study. First, the affective psychopathological dimensions were related to self-reported EI. Specifically, manic symptoms were related to better self-perception of EI, whereas depressive symptoms were associated with a worse feeling of emotional regulation. Second, patients’ insight into psychotic illness was related to better self-perception of EI and worse emotional management in the performance-based test. Third, no significant relationships were found between psychotic dimensions or refusal of treatment and either measure of EI. Fourth, network analyses showed strong connections between psychotic symptoms and insight dimensions, depressive symptoms and negative symptoms, and manic symptoms and self-perceived emotion regulation. Fifth, discrepancies between performance-based and self-reported EI measures were revealed by the absence of correlations between both measures, with the exception of a significant correlation between emotional attention and managing emotional relationships.

Our results showed no relationship between the positive, negative, or disorganisation dimensions and EI, either performance-based or self-reported. However, this relationship remains unclear in literature. Tabak et al.53 found that patients who paid more attention to their emotions experienced more psychiatric symptoms, and it has been reported that clinical status and the presence and severity of symptoms are associated with both perceived and performance-based EI deficits.54,55 Moreover, it seems that patients who achieved greater benefits at the functional level in interventions aimed at working on the perception of emotions were those with less positive and negative symptomatology,56 and a mediating effect of negative symptoms versus EI on independent and self-care living has also been found.26 These results were at first look at odds with ours since we did not find significant relationships between positive, negative, and disorganization dimensions and emotional intelligence assessments. However, differences across samples and studies may account for this discrepancy, as our patients were evaluated once they achieved clinical stabilization. These results are consistent with existing debates about functional recovery in the early stages of schizophrenia and the different presentations that symptoms can have depending on the stage of the disease and the response to treatment.1 In fact, EI, likewise social cognition57 may have trait and state properties, resulting in fluctuating performance in the presence of psychiatric symptoms, but maintaining a set of emotional competencies that are stable in individuals’ behaviour.

Patients with higher levels of depression showed lower perceived emotional regulation, even though this association remained at the level of a trend toward statistical association. This association suggests that the persistence of negative mood can lead to ineffective strategies and emotional suppression, prolonging depressive symptoms, accentuating emotional dysregulation, and creating a negative cycle. In this regard, difficulty in finding adaptive strategies to achieve adequate affective regulation to cope with different situations aggravates the symptoms of the disorder.58,59 Moreover, deficits in EI, such as difficulty in processing and identifying emotions, may have a negative impact since they are associated with several disorders such as anxiety and depression in schizophrenia.60

Patients with more manic symptomatology showed a trend towards significance in perceiving themselves as having a greater capacity to understand and regulate their emotions. A euphoric mood may influence how individuals view themselves and impair emotion regulation through maladaptive strategies toward positive emotions. In a previous study, our group’s findings showed that self-reported and objective cognitive testing were discrepant when considering the role of affective symptoms.61 Moreover, it has been reported that the regulation of positive emotions is a notable challenge for those at risk for mania, as this predisposition is associated with considerable difficulties in controlling their positive feelings.62

Our results showed that patients with greater awareness of insight paid significantly more attention to their emotions. It is possible that people with psychosis who are more aware of their symptoms and internal emotional experiences have a greater ability to identify their own emotions and those of others, as well as their limitations. This awareness of the illness is related to a lower presence of self-compassion, which is a powerful predictor of depression following a psychotic experience.63 Additionally, patients exhibiting a greater degree of unawareness of their illness showed a trend towards greater perceived emotional regulation. This may be due to the fact that they may be unaware of how they feel emotionally, leading to the perception that they are regulating their emotions effectively. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with the results of Peralta et al.8,9 on social exclusion and predictors of psychotic disorders, highlighting the crucial role of subjective experiences in achieving long-term goals.

One original feature of this study was the analysis of patient-reported outcome measures (PREMS, subjective, patient-reported experience measures) and PROMS (patient-reported outcome measures) evaluated by a professional. Discrepancies may exist between an individual’s self-perception and self-assessment of emotional abilities and their actual performance in emotionally demanding situations. Individuals may believe that they have a robust ability to regulate their emotions to cope with challenging emotional situations.64 However, when faced with a real situation that requires the regulation of difficult emotions, individuals may not respond as expected. Overconfidence on emotion perception tests compared to actual performance on SC objective tests has been reported65,66 and the need to analyse SC in ecological contexts based on real interactions.28 This overconfidence has been explained by the phenomenon of “unskilled and unaware” (Dunning-Kruger effect).64 Although this may have positive effects, such as higher self-esteem,67 it has been linked to undesirable behaviours, such as gambling problems68 and lower performance in social and neurocognitive domains in patients with schizophrenia.69 In fact, the EI theoretical model proposed by Salovey and Mayer21 considers EI as an ability and defends that people are poor at estimating their own levels of intelligence (referring also to general intelligence).70 However, these authors also consider that the assessment of emotional intelligence must be followed by the assessment of the reflective processes that accompany mood states, or what they call the “meta-mood experience”.24 Hence, the way people understand their own emotions is different from their understanding of how others experience and manage their emotions. Our results support the idea that both assessments are complementary and that there is a subjective component in emotional intelligence which is related to affective symptoms and insight. These findings are consistent with studies showing that self-perception of one's own emotional experiences and measures of competence may relate differently to other variables, and that self-report instruments cannot substitute for competence instruments but should be considered additionally.71,72 Studies comparing TMMS-24 with MSCEIT, and more specifically, in people with mental disorders, are very scarce. Comparing both instruments, only the MSCEIT was able to discriminate between different clinical groups and subjects with different psychological disorders, including dysthymia, agoraphobia, and cocaine addiction.54 These differences may be due to the fact that these instruments measure different emotional skills and abilities and therefore may yield different results. The TMMS-24 is a measure of trait EI, while MSCEIT measures ability EI.73 This conceptualization comes from the different definitions of EI, leading to three main models: the ability model, the mixed model, and the trait model.74 Therefore, future research could differentiate the two types of EI measurement, self-reported and performance-based, between different severe mental disorders to investigate possible discrepancies and tailor treatments and interventions for each of them.

Finally, to gain deeper insight, a network analysis was incorporated, providing an analysis that controls for the effect of the correlations between all variables in the model. Network models provide a different approach to psychopathology than traditional categorical classification systems. These models consider that symptoms are connected but do not assume a latent common cause of these symptoms and criticise the use of global scores to assess psychopathological status.75 In a network, nodes are symptoms, and the connections between nodes are interactions between symptoms.76 Network analysis revealed a strong association between psychotic dimensions (positive, negative, and disorganised) and insight dimensions, consistent with previous findings on the relationship between insight, SC, and functioning.33,77 Depressive symptoms were associated with negative symptoms, as previously described in network analyses,78 while mania was related only to emotional regulation. The nodes of self-reported and performance-based EI were not associated with each other or with other variables, except for emotional regulation, which was positively related to mania, unlike what has been reported in studies on the theory of mind and SC in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis.34,79 In addition, our results show a central role of insight in the network composed of clinical symptoms, insight, and both assessments of EI (performance-based and self-reported). In fact, insight was related to both EI measures in the network. The use of dimensional approaches, such as network models, may have therapeutic implications, considering the most central nodes as intervention targets. As the network does not provide a causal relationship, a bidirectional relationship may be assumed. Considering the network approach, connections shown by the network may mean that highly influential nodes maintain others active, and these connections may have treatment implications.76,80 Hence, an improvement in one node (e.g. insight) may have a direct effect on positive and negative symptoms, but also in the way patients recognise and regulate their emotions and are capable of understanding how to manage emotions in a simulated situation. Interestingly, the absence of feeling ill was the node with the highest expected influence and strength values, demonstrating that it may play a crucial role in the interaction with clinical variables. Also, predictability showed by the insight and EI nodes may have intervention implications, since changes in one of these variables may be associated with changes in those variables which are highly explained by their neighbours.81

Our study has some limitations. First, the TMMS was self-reported; therefore, the results may be biased by social desirability.82,83 However, self-reported measures have been demonstrated to be useful and informative for patients with psychotic disorders.61,84 Second, we did not have a control group to compare TMMS-24 scores. Normative data provided by the authors of the scale were used.44 Third, the objective was to study people with psychotic disorders that are heterogeneous. High variability in emotion processing has been observed in patients with bipolar disorder, with some individuals exhibiting significant deficits and others performing similarly to healthy controls.85 In schizophrenia, there has been reported lower awareness of the illness itself and of certain symptoms such as anhedonia and unsociability, as well as of its social consequences, compared to patients with bipolar disorder.86 Furthermore, while in schizophrenia a higher total TMMS score has been associated with greater independent living, but also with an increase in symptoms when attention to feelings increases, in bipolar disorder it has been linked to better social functioning and a reduction in manic symptoms.53 Thus, diagnostic heterogeneity may have contributed to the absence of associations between clinical and EI variables. Furthermore, clinical stability was established by clinical consensus; it would have been desirable to consider the operational criteria of psychopathological remission. In addition, the sample size limits the generalisation of the results. Recruitment was naturalistic; therefore, we did not determine an estimate of the sample size a priori. Fourth, the cross-sectional design can be considered a limitation of this study. For future research, it would be interesting to evaluate emotional intelligence longitudinally to determine whether these deficits are maintained over time or improve as symptoms diminish. Fifth, insight was assessed using only three items from the AMDP system, which provides a useful but less comprehensive measure than specialised scales such as the SUMD or SAI-E. However, this choice concisely reflects David's model,42 being aligned with the objectives of our study. Finally, network analyses imply replicability challenges in this study. Network analyses are exploratory and data-driven methods that may be affected by some methodological decisions which may hinder the replicability of results and therefore should be interpreted with caution.87

In conclusion, EI, understood as a dimension of SC, is a construct related to affective symptoms and insight in clinically stable patients with psychosis. Furthermore, it may be important to differentiate between how patients perceive their emotional intelligence and performance-based measures of emotional processing. Individuals’ emotional perceptions may determine how they will respond to interventions aimed at improving their quality of life and increasing their functioning.

FundingThis work was funded by the Carlos III Health Institute, Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, European Regional Development Fund (ERDF/FEDER) (PI 19/1698 and RD24/0003/0015), and Government of Navarra’s Health Department (20/21). Both had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Open access funding provided by Universidad Pública de Navarra.

Ethical considerationThis study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethical Committee of Navarra (Spain). All patients provided written informed consent, in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki

CRediT authorship contribution statementE. Rosado: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. A. Zarzuela and G.E. Berrozpe: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. X. Ansorena and Julen Chato: Writing – review & editing. V. Peralta and MJ Cuesta: Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AM Sánchez-Torres: Supervision, Investigation, Data Curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.