In recent years, tensions have risen between the legislative context of Mental Health Laws (MHL) across Europe and the provisions set forth by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, pointing to ongoing discussions about autonomy and the conditions under which involuntary measures may occur.

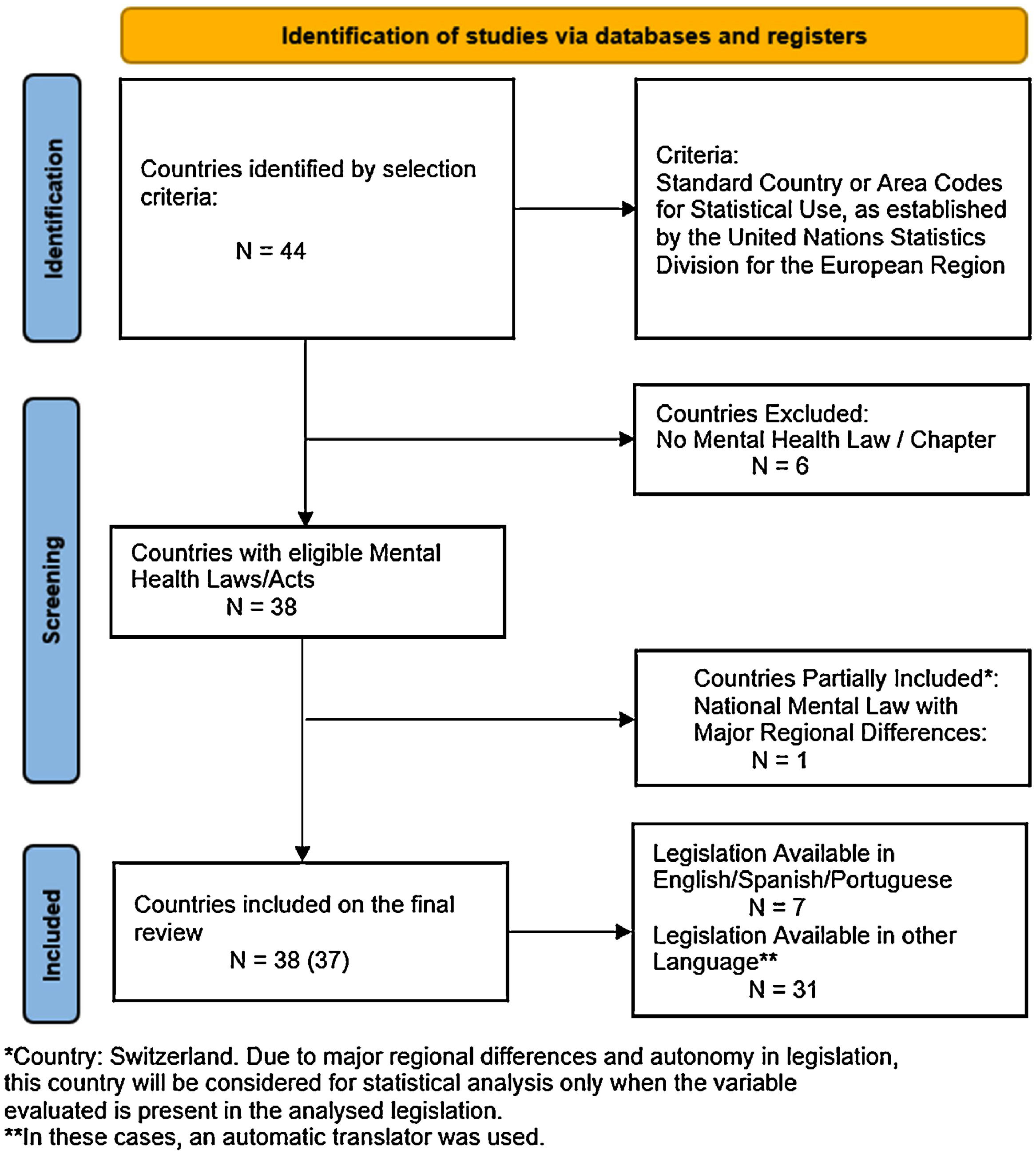

MethodsA comparative analysis of national Mental Health Laws (MHL) across 44 European countries was conducted, focusing on legal frameworks for involuntary psychiatric care. It identifies 38 countries with MHL, excluding six without national legislation or where mental health is governed by regional frameworks. Data were collected from official sources and verified through the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2020. A total of 38 MHLs were analysed across four key domains: general definitions, formal procedures for involuntary admission, emergency procedures, and best practices in involuntary care.

ResultsAll MHLs require the presence of a mental disorder for involuntary admission, with 92 % also citing dangerousness. However, only 45 % provide a legal definition of mental disorder, and 29 % reference international diagnostic criteria (e.g., ICD, DSM). Procedures for involuntary admission are typically initiated by healthcare professionals (66 %), with courts serving as the primary deciding authority in 76 % of cases. Emergency detention durations vary, with many countries lacking clear limits. Best practices—such as distinguishing admission from treatment, allowing outpatient commitment, and requiring periodic legal review—are applied inconsistently. Only 14 countries explicitly prohibit controversial practices like psychosurgery or non-consensual ECT. While most laws emphasize protection of rights, the study highlights ethical tensions with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), particularly around involuntary measures. Limitations include reliance on translated texts, the omission of subnational laws, and the lack of enforcement analysis.

ConclusionsThese findings highlight the need for harmonized legal standards, enhanced procedural safeguards, and stronger rights-based frameworks in mental health legislation across Europe. Reforms should aim for standardized legal definitions, clearer procedures, and alignment with international norms, while remaining sensitive to clinical and cultural contexts.

Mental health legislation (MHL), historically rooted in both social and medical models of disability, has played a significant role in shaping the nature of, and access to, mental health care, as well as influencing public perceptions of mental disorders, including stigma and discrimination. While the origins of Western mental health law can be traced back to the Middle Ages, the past 150 years have been particularly important in the development of legislation that justifies involuntary admission and treatment primarily based on the need for care or the perception of dangerousness.

Legislation has sought to ensure that human rights remain central to all actions in mental health care.1,2 Although many early laws have since been revised, their principles continue to influence contemporary policy.1,3

Mental health laws have historically reflected prevailing understandings of mental illness, drawing from psychological, somatic, social and spiritual paradigms, as well as contributions from anti-psychiatric movements in recent centuries. While anti-psychiatric movements were instrumental in the process of deinstitutionalisation, exemplified by Italy’s 1978 Basaglia Law, which laid the foundations for global reforms,1 they have also, in some instances, damaged the already fragile public image of mental healthcare, and undermined its perceived importance.4

Although the number of people with mental disorders in psychiatric institutions has declined over the past 50 years, many individuals continue to face unmet mental health needs. At the same time, rates of imprisonment and homelessness have risen. In 2020, a WHO European survey reported that mental illness was the most common condition among people in prison, affecting 32.8 %, and suicide was the leading cause of death.5 A 2015 survey across 6 European countries reported an increase in the number of forensic beds, while general psychiatric beds decreased in 5 countries. In only 2 countries this reduction in general psychiatric beds exceeded the increase in the number of forensic beds, indicating an increase in containment.6

Recent decades have seen a shift towards anti-reductionist views of mental disorders. George Engel’s biopsychosocial model emphasized the interaction between biological and psychosocial factors, while Michael Oliver’s 'social model of disability', highlighted how societal structures marginalized individuals with impairments, limiting their full participation in society.7 These conceptual developments have been accompanied by major changes in legislation, with new international frameworks encouraging a human rights-based approach to mental health care.1

In 1996, the WHO defined the ten Basic Principles of Mental Health Law,8 which have provided a foundation for more recent and evolving guidelines. These principles address the importance of prevention, the need for every mental health assessment to be conducted in accordance with international clinical standards, including diagnosis, choice of treatment, determination of competence or risk of harm to self or others, and the centrality of a patient-centred approach, with limits on restrictive measures, and empowerment through self-determination and the right to support in exercising it, stating that (free, informed and documented) consent is required before any type of intervention. The document goes further by calling for the mandatory availability of review procedures (including proposals for their regulation) and an automatic periodic review mechanism to be put in place for any treatment or hospitalisation with long-term effects.

The WHO further advanced these standards with the publication of "Mental health, human rights and legislation: guidance and practice", hereafter referred to as the WHO Guideline.1 This document provides comprehensive guidance on how to design, develop and implement good practice in mental health care. It identifies the challenges associated with current legislation and highlights the need for reforms that are consistent with the international human rights framework. It outlines key principles that MHL should include, with examples of rights-based provisions; and explains how to develop, implement and evaluate MHL using a rights-based process. The WHO Guideline serves as a steppingstone for countries to build upon their legislation (the jure) and apply it in a practical context (de facto). While, in some respects, it is shaped after the basic principles outlined above, it also introduces key changes. This document has been developed in line with the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) ,9 a foundational document for human rights discussions in subsequent years. The CRPD builds on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,10 the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights11 and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.12 It emphasises the promotion of autonomy, community integration, full participation and support. Nonetheless, ethical concerns have surged, arguing that the CRPD’s absolute prohibition of involuntary interventions disregards clinical contexts where impaired decisional capacity, lack of insight, and immediate risk impose ethically contested protective measures, revealing a profound tension between strict autonomy-driven frameworks and the practical requirements of psychiatric care.13,14

As a follow-up to the CRPD, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights developed the International Principles and Guidelines on Access to Justice for Persons with Disabilities15 in 2020, which set out 10 clear principles to ensure equality before the law and the right to be heard and to participate. The first principle ("All persons with disabilities have legal capacity and therefore no one shall be denied access to justice on the basis of disability") asserts that States should "repeal or amend laws (…) that subject defendants with disabilities to detention in a prison, mental health facility or other institution for a definite or indefinite term (sometimes referred to as "care-related hospitalisation", "security measures" or "detention at the pleasure of the governor") on the basis of perceived dangerousness or need for care”. This document also reaffirms the need for appropriate measures to be taken to enable persons with disabilities to have access to justice, including but not limited to: the creation of an environment in which persons with disabilities can testify, and the review of procedures in which a person may be deprived of his or her personal liberties. Other international bodies such as the Subcommittee for the Prevention of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (SPT), the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Council of Europe have also contributed to the discussions with important statements. Important stakeholders include psychiatric associations, such as the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) and the American Psychiatric Association (APA), which have established important ethical standards for psychiatric practice through conventions such as the 1996 Madrid Declaration.16

Building on the CRPD, the Steering Committee for Human Rights in the fields of Biomedicine and Health of the Council of Europe has drafted the Recommendation on respect for autonomy in mental healthcare, now pending adoption by the Council of Ministers, to call on member States to integrate respect for autonomy in MHL frameworks and care.17 In this context, the present study aims to examine the content of national MHL across European countries, focusing on provisions relating to involuntary care, emergency procedures, legal definitions and legal safeguards. Beyond a descriptive overview, this article seeks to critically assess how these laws align with internationally recognised ethical frameworks and human rights instruments, such as the CRPD, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the Madrid Declaration and the WHO Mental Health Action Plan. Key research questions guide this analysis: 1) How consistently do national MHLs define and regulate criteria for involuntary admission and treatment? 2) To what extent do these laws incorporate procedural safeguards that uphold legal capacity, informed consent and patient autonomy? 3)How do these legal frameworks support - or hinder - the transition to person-centred, community-based mental health care? These guiding questions informed the structure of the analysis, and support a critical reflection on the ethical adequacy, coherence and future directions of mental health legislation in Europe.

MethodologyThis study undertook a comprehensive analysis of national MHL across Europe. The methodological approach comprised the following steps:

Geographical scope and country selectionCountries were selected based on a geographical definition of Europe, following the Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use (Series M, No. 49) established by the United Nations Statistics Division. This classification led to the inclusion of 44 European countries.

Eligibility criteriaThe following inclusion criteria were applied:

- •

The country has a standalone national Mental Health Law or Act; or

- •

The country has a distinct chapter or section on mental health within a broader legislative framework (e.g., General Health Acts).

Exclusion criteria:

- •

The country does not have a national MHL, with mental health governance regulated instead by interstate or regional legal frameworks.

- •

In cases where a national MHL exists but regional differences in application are present, only provisions explicitly defined at the national level were considered for statistical purposes.

Data collection process: Relevant legislation was identified and collected between 21 November and 5 December 2024.

Primary sources and legal search strategy: The primary method of data collection involved a systematic search of official government websites for each of the 44 countries to locate the applicable MHL. Three possible scenarios were considered:

1. Laws available in English, Portuguese or Spanish - these documents were reviewed and analysed directly in their original language.

2. Laws available in other languages - in these cases, automatic translation tools were used to translate the texts into English for analysis purposes.

3. Law not found through official channels - where legislation could not be located through primary sources, secondary confirmation was sought using country profiles from the World Health Organization Mental Health Atlas 202,018 to verify the presence or absence of a national MHL or equivalent framework. Each law identified was1 cross-referenced with secondary sources, such as international reports and treaties, to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness, and2 discussed between experts (CA in law and LM in psychiatry).

The criteria analysed were as follows:

- •

Existence of legal criteria for involuntary admission.

- •

Authority entitled to request a formal psychiatric evaluation.

- •

Deciding authority for admission.

- •

Legal definition of mental disorder.

- •

Responsible professional for initial assessment.

- •

Distinction between admission and treatment procedures.

- •

Possibility of compulsory outpatient treatment.

- •

Existence of a mandatory patient council or oversight body.

- •

Time frame between assessment and legal decision.

- •

Maximum duration permitted for emergency admission.

- •

Deciding authority for emergency admission.

- •

Maximum legal duration of initial placement.

- •

Re-approval or renewal period for compulsory treatment.

- •

Legal prohibition of specific practices.

These criteria were grouped into four thematic categories, each addressing different aspects of the national mental health legal framework.

1.General legal definitions: covering the foundational concepts and definitions that determine that structure the scope and applicability of mental health legislation.

2. Procedural requirements for involuntary admission: addressing legal procedures and decisions, and the responsible authorities.

3. Emergency procedures and exceptional circumstances: focusing on expedited admission procedures, often operating outside standard legal safeguards.

4. Consent and best practice: examining provisions that regulate the treatment of individuals lacking capacity to consent.

Firstly, while a systematic approach was employed to identify and review mental health laws, reliance on automatic translation tools for non-English, non-Portuguese, and non-Spanish sources introduces the possibility of semantic inaccuracies and may compromise legal nuances of certain terms and provisions. These translations are not equivalent to certified legal interpretations, and as such, the findings should be viewed as indicative rather than definitive.

A further limitation lies in the exclusion of subnational legal frameworks in federal or decentralised systems, such as Germany, and Switzerland. In these cases, national-level legislation was prioritised to maintain cross-country comparability, but this inevitably overlooks significant legal variation within those jurisdictions.

Additionally, although this study provides a broad mapping of legal provisions, it does not undertake a detailed policy or contextual analysis. Legal texts provide the formal framework, but real-world applicability depends on a country’s judicial practices, healthcare infrastructure, and cultural context, factors which fall outside the scope of this analysis. Future research should engage in-depth, country-specific legal and policy analyses to complement and extend our findings.

ResultsThe search identified 44 countries (Table 1, Supplementary Materials). Andorra, Czech Republic, Vatican City, Germany, Liechtenstein and Slovakia had no specific MHL. To ensure the absence of legislation, the country profile of each country was consulted in the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2020. Of these 6 countries, 3 are considered microstates, which affect their legislative framework due to specificities and possible dependencies on other countries' legislation/health services.19 Slovakia and the Czech Republic do not have specific legislation on mental health, both including this issue in general legislation. No historical analysis was carried out, which might have influenced the way MHL is incorporated in both countries.20 The German Civil Code covers most issues related to non-acute care of a person who is incapable of caring for themselves. However, each of the 16 Länder has the autonomy to regulate its own legislation on the remaining issues in the respective legal framework (Psychisch-Kranken-Gesetzen) .21,22

- General definitions.

Of the remaining 38 MHLs, the Swiss Civil Code (Title 11, Section 3) provides a framework and specific limitations, but at the cantonal level each canton is responsible for implementing and specifying the legal framework for involuntary hospitalisation.23 Therefore, the parameters set at the federal level are used in the discussion, but the omission of parameters is not counted for any statistical analysis.

General definitionsAll the MHLs considered refer to mental disorder as a prerequisite for their application, either in the preambles of the documents or in later articles (Table 1).

All MHL except those of Iceland, Italy and Spain (92 %) define dangerousness as a criterion. Only 1 country (Portugal) includes active refusal of treatment. "Understanding" is explicitly mentioned 8 times and "need for treatment" 23 times.

Regarding the existence of definitions of mental disorder, 42 % do not provide a definition. Of the 21 countries that provide definitions, 11 refer to international standards or criteria (e.g. ICD or DSM) and 6 mention that diagnoses are made according to general medical/scientific criteria.

Formal procedures leading to involuntary admissionOf the 38 MHL analysed, only Macedonia, Sweden and Spain do not mention who can initiate the evaluation process (Table 2).

– Assessment requirements.

The most common vector was "health care providers", mentioned in 68 % of the MHLs. "Public safety" includes mentions of the police, gendarmerie or fire brigade, with 12 countries allowing this.

14 countries mentioned "family" (including words such as relatives or next of kin), with some specifying certain proximity requirements.

It should also be noted that 21 % of the laws allow any person to request a formal assessment, regardless of their role or relationship to the person being assessed.

In the majority of countries (68 %), the initial psychiatric assessment is legally required to be carried out by a mental health professional, most commonly a psychiatrist, who is specifically mentioned in 22 national laws (Table 3). In contrast, 24 % of MHLs allow any medical practitioner to carry out the initial assessment, without the need for specific mental health qualifications. Although some countries refer to the need for mental health training, these provisions often lack a clear definition or specification of the training standards involved.

– Assessment and decision-making.

Only Switzerland, Italy, Spain and North Macedonia do not explicitly state in their legislation who is responsible for carrying out the initial assessment.

Regarding the number of professionals involved in the assessment, only 27 % of countries (10 MHL) specify that more than one expert must be involved in order to produce a legally valid opinion for the purposes of formal decision-making procedures.

Involuntary emergency proceduresWith respect to the maximum duration of emergency or short-term detention, 26 % of national MHLs set a maximum duration of less than 48 h, while 37 % allow emergency detention for periods between 2 days and 1 week. In contrast, six countries do not set a specific time limit for emergency detention, either because there is no reference to emergency detention procedures or because there is no time limit in the legal framework (Table 4).

- Emergency procedures.

Regarding the authority to decide on emergency detention, 42 % of MHLs assign this responsibility to psychiatrists. In addition, general practitioners and senior health managers - including chief physicians and directors of hospitals or regional health authorities - are also frequently named as responsible decision-makers, with 8 and 7 mentions respectively in the laws analysed.

Although the maximum duration of initial placement is not necessarily part of emergency procedures, it is often linked to them and, in some legislative contexts, constitutes a direct extension of emergency detention. This parameter is not specified in 30 % of countries, while 32 % of MHLs provide for an initial placement period of less than one month. The remaining legislation shows greater variability, with maximum periods ranging from one month to up to two years.

Best practices in involuntary careAccording to the legislations analysed 58 % of countries distinguish between involuntary admission and involuntary treatment, treating them as separate legal modalities. In contrast, 29 % of countries integrate both provisions within a single legal framework, without making a clear distinction between the two procedures. Regarding the legal provision for outpatient treatment, 61 % of countries allow for compulsory outpatient treatment, often under specific conditions that are explicitly defined in the legislation. Conversely, 29 % of countries restrict involuntary treatment exclusively to inpatient settings, without allowing for alternative forms of compulsory community treatment. Less than half of the MHLs examined provide explicit definitions of coercive measures and the legal contexts in which such measures are permitted. While several countries refer to limiting or regulating coercive practices, many do not specify which measures are permitted or under what circumstances they may be used. Mandatory patient councils - legal provisions ensuring that patients can be heard by a judge or other decision-making authority - are explicitly required in 51 % of the MHLs analysed, unless waived by the patient. With regard to reauthorisation periods - defined as the interval after which a mandatory treatment order must be reviewed and renewed - the study found considerable variation between national laws. Most countries (76 %) require the first reauthorisation decision to be taken within six months of the initial authorisation. Only Poland and Belgium allow a longer initial reauthorisation interval. Notably, seven countries do not specify in their legislation the timeframe or periodicity of re-authorisation procedures (Table 5).

- Best practices.

Most of the national MHLs analysed include a preamble or general provision emphasising the protection of human rights, explicitly stating that mental health care should not interfere with individual liberties and that involuntary measures must be non-discriminatory and taken only in the best interests of the patient. These provisions often emphasise the principle of proportionality and the need to respect dignity and autonomy throughout the treatment process. A common legal clause is the prohibition of research or experimental treatment on persons who are unable to give informed consent, which reinforces internationally recognised ethical standards in clinical practice. In terms of prohibited practices, 14 countries explicitly identify specific interventions that are categorically prohibited within their legal framework. The most common prohibited practice is psychosurgery, but several laws also restrict or prohibit the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and sterilisation, particularly in involuntary or non-consensual contexts (Table 6). These bans reflect broader ethical concerns about the historical misuse of such interventions and the prioritisation of patients' rights and bodily integrity.

– Specific practices.

In the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2020, 75 % of Member States reported having a stand-alone mental health policy or plan, an increase from 68 % in 2014. Similarly, 57 % of Member States reported having a stand-alone MHL, an increase from 51 % in 2014, with 46 % having updated their mental health policy or plan and 27 % having updated their mental health law since 2017. In the WHO European Region, more than 70 % of responding countries reported the existence of a stand-alone mental health law, and even more reported the existence of a mental health policy or plan.18 These legal frameworks often address issues such as the rights of mental health service users, diagnostic criteria, procedures for voluntary and involuntary admission and treatment, community treatment orders, consent protocols for specific treatments, oversight mechanisms, provisions for offenders, and the overall governance and management of mental health services.18,24 However, in countries without specific mental health legislation - or even where such legislation exists - related areas of law (e.g. general health, social services, local government or criminal law) may contain provisions that adversely affect the rights of persons with mental illness and psychosocial disability.1 Of the 38 MHLs analysed, the date of the most recent legislative revision ranges from 1990 to 2024, with Belgium having the oldest law. However, the date of legislation approval does not necessarily reflect the quality of care; Belgium's 2010 national reform was in line with the WHO Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 and improved service delivery through community-based care.25,26 Therefore, legislative updates may signal innovation and ethical progress, but older laws do not inherently imply systemic inadequacy.

The international community remains divided on the ethical and legal justifications for involuntary measures in mental health care. Article 14 of the CRPD explicitly calls for the abolition of all deprivation of liberty based on impairment, thereby excluding involuntary care based on diagnosis, dangerousness or need for treatment.9 In contrast, a joint statement by the APA and the WPA expresses concern about the categorisation of commonly accepted psychiatric practices - such as involuntary commitment, treatment under guardianship and restraint - as forms of torture.27 Further tensions arise with Article 12 of the CRPD, which promotes supported decision-making but omits substituted decision-making, a central mechanism in most MHL that authorises health professionals or legal guardians to act on behalf of the patient.

In this study, while all the countries analysed, except Belarus, have ratified the CRPD, their MHL still relies on diagnosis-based provisions, which may conflict with Article 12, which guarantees legal capacity on an equal basis with others. The SPT accepts court-ordered involuntary treatment under strict conditions, including expert care, judicial oversight and adaptation to individual health needs,29 but the challenge remains to reconcile such practices with human rights frameworks. The Draft Recommendation of the Steering Committee for Human Rights in the fields of Biomedicine and Health will call upon member states to adopt into their MHLs a general principle of respect for autonomy in the provision of mental healthcare, by means of free and informed consent or, absent the capacity to consent, by respecting patients’ will and preferences. Any exception to that general rule would then be subject to strict legal safeguards respecting human dignity.17

Criteria crisisIn all 38 MHLs analysed in this study, the presence of a mental disorder remains a core criterion for involuntary admission, often supplemented by the requirement of danger to self or others - except in Iceland and Italy, where this is not specified. Notably, only 21 % of countries explicitly mention lack of insight as a criterion, despite its clinical relevance in assessing decision-making capacity and treatment compliance.28,29 Insight, although controversial and primarily used in the context of psychotic disorders, continues to influence perceptions of patient autonomy. However, it is crucial to recognise that most people with serious mental disorders retain the capacity to make informed healthcare decisions and should not be subjected to unnecessary paternalism.30

There is also a lack of consensus on the appropriate criteria for involuntary treatment. While the ECHR requires a finding of mental disorder through medical expertise, its severity and persistence to justify detention,31 the Council of Europe includes dangerousness, insight and need for treatment as relevant factors.32 In addition, 42 % of MHLs do not define what constitutes a mental disorder or provide diagnostic criteria, creating a risk of inconsistency and abuse. In contrast, 45 % include definitions and 29 % adhere to international standards such as the ICD or DSM,33,34 which can promote diagnostic accuracy and safeguard patients' rights. To align with the CRPD, some scholars advocate a shift from diagnosis-based models to decision-making capacity-based frameworks, thereby reducing discrimination and increasing legal coherence.35

Procedural lotteryOur findings show that legislation regarding the initiation of formal, mandatory mental health assessments vary widely between countries. In most cases (66 %), healthcare providers are the primary initiators, highlighting the role of the clinical sector in early detection and response.31 However, other actors such as emergency services (e.g. police, fire brigade) and family members - mentioned in 37 % of laws - are also empowered to initiate such processes. This diversity reflects the wider societal and institutional responsibilities in responding to mental health crises and requires robust supportive frameworks and community guidance.2,35 As disability perspectives evolve towards de-medicalisation, there is an increasing emphasis on non-medicalised crisis interventions that respect legal capacity and minimise coercion.1,9,36 Legislation plays a crucial role in shaping crisis response systems and ensuring adequate training for first responders, particularly in human rights-based approaches, de-escalation techniques and trauma-informed care.9,18 The initial assessment, typically carried out by psychiatrists in 68 % of countries, can also be carried out by general practitioners (24 %). However, the lack of international training standards raises concerns about diagnostic consistency.1,36,37,47 The ECtHR has affirmed that deprivation of liberty without medical expertise is incompatible with the CRPD,31 which further reinforces the need for specialised knowledge in such procedures.

Despite the importance of clinical expertise, our study found that in 68 % of countries a single evaluator is allowed to determine involuntary treatment, a practice contradicting international recommendations for multidisciplinary evaluations that increase objectivity and minimise bias.1,9 In addition, 76 % of countries vest final decision-making authority in the courts, underscoring the role of the legal system in ensuring transparency, oversight and protection of individual liberties.6,9,27,38 In contrast, a few countries delegate this authority to non-judicial or undefined roles. In Norway, decisions are made by a 'mental health expert', although the qualifications for this role are not specified. In Malta, a Commissioner appointed by the Prime Minister has this responsibility, with no requirement for legal or clinical expertise. In the Netherlands, the Head of Establishment assumes this role, raising concerns about potential institutional bias and conflicts of interest. Such models, while culturally contextual, pose risks in the absence of formal legal or ethical safeguards. The SPT warns that any involuntary detention not ordered by a competent and independent judicial authority constitutes arbitrary detention.38 Legislative reforms must therefore address training and standardisation, with organisations such as the EPA advocating for improved professional training, despite the challenges posed by cultural heterogeneity, and proposing a European board examination as a possible harmonisation mechanism.35,39

Ambiguity on best practicesThe ethical and legal tensions surrounding involuntary treatment remain a key challenge in MHL. The Madrid Declaration (1996) emphasised that 'no treatment should be provided against the patient's will, unless withholding treatment would endanger the life of the patient and/or others", and reiterated that care must be in the best interests of the patient.16 This distinction between admission and treatment is crucial, with important ethical complications, but is often blurred in many MHLs, where both are treated as a single legal process. While more than half of European MHLs distinguish between admission and treatment, others do not, leading to legal ambiguity and gaps in interpretation. For example, Iceland's legislation applies 'dangerousness' only to admission criteria, not to treatment. The Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture also states that involuntary admission should never imply an automatic right to administer medication without consent.38 In contrast, the ECtHR asserts that all interventions must have a therapeutic purpose,31 further challenging the use of admission solely as a security measure. Although trends towards deinstitutionalisation are encouraged, they need to be carefully managed as underfunded transitions can lead to increased involuntary admissions.36,40 Legislation needs to adapt and promote rights-based frameworks that balance safety, autonomy and ethical standards of treatment.

An important aspect of this development is outpatient commitment (OPC), which is legally permitted in only 61 % of countries. OPC typically involves a court-ordered commitment to engage in community-based treatment while remaining socially integrated. Although OPC models vary, evidence suggests that they can reduce rehospitalisation and improve treatment adherence, particularly when embedded in long-term community-based services.41–43 The WHO Mental Health Atlas (2020) reports that over 35 % of mental health budgets in high-income countries continue to be allocated to psychiatric hospitals,18 despite community-based care being more cost-effective and ethical. However, not all countries have implemented OPC frameworks, often due to restrictive legislation. Legal systems therefore play a crucial role in enabling or hindering this structural change. The distinction between admission and treatment must be clearly defined in law to ensure the appropriate application of the OPC.

The autonomy dillemaAlthough some countries (e.g. Mexico) have enacted complete bans on coercive measures, most MHL continue to allow them, interpreting the CRPD in different ways. France and the Netherlands, for example, justify restraint as a last resort and emphasise the need for accountability, clear clinical guidelines and ethical oversight where such measures are permitted.6,8,31,44

While coercive practices remain prominently debated in global ethical and legal discourse, several interventions once considered commonplace are now unequivocally deemed ethically unacceptable. In 2015, Juan E. Méndez, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, explicitly advocated for an absolute prohibition of coercive medical interventions, with particular reference to psychosurgery, highlighting its irreversible nature and potential classification as torture.1,27,32,36,38 Similarly, coercive sterilisation, frequently linked to violations of women’s reproductive and human rights, has been explicitly condemned by the European Parliament’s Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, which demands rigorous safeguards and independent verification of informed consent.27,36,45,46 On a related but distinct front, contemporary electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)—a medically reversible intervention with demonstrated safety and clear clinical indications—necessitates further regulatory clarification. Certain clinical circumstances preclude patient consent yet yield significant therapeutic benefit, raising complex ethical questions. Nonetheless, international psychiatric bodies, including the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), offer limited guidance concerning non-consensual ECT administration,47 and five existing mental health laws explicitly prohibit its involuntary use.27,32,36

Enhancing legal agency is central to ethical reform, yet only half of MHLs require the presence of patient councils, reflecting a persistent gap in patient participation and procedural justice.1,15 Legal Capacity, a cornerstone of the CRPD, needs to be actively protected by legislation.1,14,15,48 Equal representation in legal proceedings should be more than symbolic - systems must ensure that people with mental disorders can meaningfully exercise their rights. Finally, timelines for assessments and decisions vary, with many countries allowing up to a week, others extending to a month or more, and some, such as Greece, requiring more rigorous review mechanisms after six months.

Emergency proceduresOur study showed that the maximum duration of involuntary emergency detention varies widely between national laws, with 39 % of countries limiting it to between three and seven days, while six countries do not specify a time limit at all. Such omissions raise critical concerns, potentially allowing indefinite detention or rendering early decisions legally invalid if no final procedure follows. Although there are no uniform international standards for review periods, regular evaluations are essential to assess the continuing need for care and to develop appropriate follow-up plans.1,38

Emergency procedures, originally designed as protective and public health measures, are particularly vulnerable to misuse, overuse and violation of individual rights.1 Even though their use in specific acute situations can be acknowledged, the focus should shift towards minimizing them in favour of more effective, rights-based preventive mechanisms. Research consistently shows that voluntary care produces better outcomes than involuntary admission, and that preventive strategies such as rehabilitation can reduce reliance on emergency interventions.49,50 Capacity building for health professionals, first responders and legal staff is essential, including training in de-escalation, prevention of violence, legal representation and discrimination.1,14,15,48 Models such as crisis intervention teams and mental health co-response units have been shown to reduce involuntary admissions and police use of force.50 Furthermore, emergency detention is often carried out without a comprehensive psychiatric assessment by inadequately trained professionals. According to the ECtHR, an immediate examination by a medical expert is required after detention, with a psychiatric evaluation always mandatory.31,38

Strengths and limitationsThis is the first study to compare European MHL in a centralized and autonomous manner, systematically analysing primary legal sources without reliance on third-party interpretations and directly assessing alignment with key international human rights instruments such as the CRPD, ECHR, and WHO guidelines. However, the study has some limitations. Firstly, the reliance on official government websites and publicly available documents means that the availability and completeness of data varied considerably between countries. In cases where automatic translation tools were used, it may have introduced interpretive inaccuracies and compromised the legal nuances of certain terms and provisions. Secondly, while secondary confirmation through the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2020 (as well as other studies) provided useful verification, this source is itself based on self-reported data from national authorities, which may be subject to reporting bias, decentralisation, or discrepancies between de jure legislation and de facto implementation.18,20,24,27 In addition, the exclusion of subnational legislative variations - particularly relevant in federal or decentralised systems - may have limited the scope of the analysis. The lack of historical or political contextual analysis also limits the understanding of how these laws have evolved and are currently operationalised. Furthermore, the study focused on the presence or absence of legal provisions without assessing the effectiveness, enforcement or ethical quality of these laws in practice.

ConclusionsThis study provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of national Mental Health Laws (MHL) across 38 European countries, systematically mapping legislation across four key domains: general definitions, formal procedures, emergency measures, and best practices. this analysis shows legal standards and divergences in the conceptualization, regulation, and safeguarding of mental health care. Significant findings include a shared reliance on mental disorder diagnoses and dangerousness as core criteria for involuntary admission, a wide variability exists in procedural safeguards, definitions of coercive measures, and oversight mechanisms and that only a minority of countries clearly differentiate between admission and treatment, prohibit specific coercive practices, or provide strong patient representation in decision-making processes.

Despite the widespread ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), our analysis suggest that MHLs continue to rely on substituted decision-making and diagnostic-based frameworks, which may conflict with the Convention’s emphasis on legal capacity and non-discrimination. The persistence of insufficiently protective laws in some jurisdictions underscores the urgent need for harmonized, rights-based reforms that align with international human rights standards. Indeed, while legal updates alone do not guarantee ethical care, they are essential for shaping systems that respect autonomy, minimize coercion, and promote therapeutic justice. Overall, this research contributes to the growing field of comparative mental health law by offering empirical data that can inform policy dialogue, advocacy, and legal reform. However, to fully understand the ethical and practical implications of MHL, future studies should assess implementation practices, patient experiences, and the impact of emerging models such as supported decision-making and community-based care.

Recommendations- European psychiatric bodies should collaborate to develop a standardized, human rights-aligned definition of ‘mental disorder’ for Mental Health Laws, incorporating international standards (e.g., ICD, DSM), clear clinical criteria, and explicit provisions for assessing decision-making capacity.

- National laws should explicitly distinguish between involuntary admission and involuntary treatment, clearly defining each as separate legal processes to protect patient rights and minimize legal ambiguities.

- Clearer international standards and frameworks should be established to guide procedural legislation, including standardized initial assessments, criteria for emergency measures, and mandatory involvement of multidisciplinary teams (rather than single evaluators).

- Mandatory patient representation mechanisms (e.g., patient councils, legal advocates) should be explicitly required in MHLs to enhance patient autonomy, ensure procedural justice, and protect individuals’ rights during involuntary care. Countries must integrate explicit requirements to respect patient preferences and autonomy, implementing supported rather than substituted decision-making wherever possible.

- European countries should set clear, standardized maximum durations for emergency detention, with robust oversight mechanisms to prevent misuse and indefinite detention. Emergency detention should be accompanied by a legally mandated psychiatric evaluation, conducted by adequately trained mental health professionals within a clearly defined timeframe.

- Stringent regulations should be implemented regarding coercive practices, with clear legal and ethical guidelines delineating conditions under which such interventions might be permitted.

- Legislation should actively facilitate and clearly regulate involuntary outpatient commitment, promoting less restrictive, community-based treatment options and reducing reliance on inpatient care.

- National psychiatric associations and governments must jointly develop and implement comprehensive training standards and certification processes for all professionals involved in involuntary mental health procedures, including psychiatrists, general practitioners, judicial authorities, and emergency responders.

- Future legislative reforms and policy recommendations should explicitly acknowledge and integrate the historical, cultural, and systemic contexts of each country.

- European psychiatric bodies and governments should jointly establish monitoring mechanisms and periodic reporting obligations to evaluate the practical implementation, human rights compliance, and outcomes of MHLs.

No ethical approval was required for this manuscript, as it does not involve human participants, animal subjects, or identifiable personal data.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

All authors declare no conflict of interest.