The pandemic derived from the SARS-CoV-2 infection led to changes in care for both relatives and intensive care patients during the different waves of incidence of the virus. The line of humanization followed by the majority of the hospitals was seriously affected by the restrictions applied. As an objective, we propose to know the modifications suffered during the different waves of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Spain regarding the policy of visits to patients in the ICU, monitoring at the end of life, and the use of new technologies. of communication between family members, patients and professionals.

MethodsMulticenter cross-sectional descriptive study through a survey of Spanish ICUs from February to April 2022. Statistical analysis methods were performed on the results as appropriate. The study was endorsed by the Spanish Society of Intensive Nursing and Coronary Units.

Results29% of the units contacted responded. The daily visiting minutes of relatives dropped drastically from 135 (87.5–255) to 45 (25−60) in the 21.2% of units that allowed their access, improving slightly with the passing of the waves. In the case of bereavement, the permissiveness was greater, increasing the use of new technologies for patient-family communication in the case of 96.5% of the units.

ConclusionsThe family of patients admitted to the ICU during the different waves of the COVID-19 pandemic have suffered restrictions on visits and a change from face-to-face to virtual communication techniques. Access times were reduced to minimum levels during the first wave, recovering with the advance of the pandemic but never reaching initial levels. Despite the implemented solutions and virtual communication, efforts should be directed towards improving the protocols for the humanization of healthcare that allow caring for families and patients whatever the healthcare context.

La pandemia derivada de la infección por SARS-CoV-2 propició cambios en los cuidados tanto a familiares como a pacientes de cuidados intensivos durante las diferentes olas de incidencia del virus. La línea de humanización seguida por la mayoría de los hospitales se vio gravemente afectada por las restricciones aplicadas. Como objetivo, planteamos conocer las modificaciones sufridas durante las diferentes olas de la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2 en España respecto a la política de visitas a los pacientes en UCI, el acompañamiento al final de la vida, y el uso de las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación entre familiares, pacientes y profesionales.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo transversal multicéntrico mediante encuesta a las UCI españolas desde febrero a abril de 2022. Se realizaron métodos de análisis estadísticos a los resultados según lo apropiado. El estudio fue avalado por la Sociedad Española de Enfermería Intensiva y Unidades Coronarias.

ResultadosRespondieron un 29% de las unidades contactadas. Los minutos de visita diarios de los familiares se redujo drásticamente de 135 (87,5–255) a 45 (25−60) en el 21,2% de unidades que permitían su acceso, mejorando levemente con el paso de las olas. En el caso de duelo, la permisividad fue mayor, aumentando el uso de las nuevas tecnologías para la comunicación paciente-familia en el caso del 96,5% de las unidades.

ConclusionesLa familia de los pacientes ingresados en UCI durante las diferentes olas de la pandemia por COVID-19, han sufrido restricciones en las visitas y cambio de la presencialidad por técnicas virtuales de comunicación. Los tiempos de acceso se redujeron a niveles mínimos durante la primera ola, recuperándose con el avance de la pandemia pero nunca llegando a niveles iniciales. A pesar de las soluciones implementadas y la comunicación virtual, los esfuerzos deberían encaminarse a la mejora de los protocolos de humanización de la asistencia sanitaria que permitieran el cuidado de familiares y pacientes cualquiera que sea el contexto sanitario.

What is known?

The COVID-19 pandemic, in its different waves, both nationally and globally, slowed down the development of quality and humanisation policies in intensive care units, reducing patient and family satisfaction.

What this study contributes?

With the COVIFAUCI study, we aimed to map out how restrictions on access to visits, use of new communication technologies and bereavement care evolved over the first four waves of the pandemic in Spain.

Study implications

The contribution of this study could help future research with respect to the development of adaptive strategies and protocols for the humanisation of care for future health contingencies, helping care managers and nurses to carry out their work in an optimised way regardless of the health context.

During the last decade, the participation of family members in the care and attention of critically ill patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICU),1 has been encouraged, given the multiple benefits for both parties described in the literature.2 For this reason, the creation of the so-called "Open Door ICUs"3 has been promoted, advocating a visiting policy adapted to the needs of patients (flexible hours, inclusion of children and bereavement support), removal of unnecessary barriers, safeguarding of the principle of autonomy and facilitation of communication between patients, relatives and professionals.4 Different studies have shown the benefits of opening the ICU, having described an increase in patient satisfaction, as well as a reduction in the incidence and duration of episodes of delirium.5,6 Similarly, an open ICU with professionals trained in its operation can reduce the risk of developing psychological complications in patients and their families.7

The process of informing relatives is also crucial, with one of the main demands identified as the need to receive more information from professionals, followed by the need for proximity to their sick relative.8,9 Furthermore, in contexts as delicate as the end-of-life stage, the units must have specific protocols for patient care in this situation, guaranteeing relatives the possibility of saying goodbye and mourning their loved ones.10,11

Against this backdrop, there are lines of research such as the "HU-ICU Project", which aims to humanise intensive care, serving as a forum for patients and professionals, bringing the ICU closer to the population and encouraging training in humanisation skills.12 COVID-19 caused a health crisis of a magnitude unknown in the modern era that forced a rapid increase in the number of ICU beds. This required, especially in the first waves, the incorporation of personnel who were not always trained in the attention and care of the critical patient.13 This substantially changed the way healthcare professionals communicated with patients, who had to spend long periods in strict isolation and were unable to receive visitors.14 Around the world, restrictions on access to accompany hospitalised patients on conventional wards and in ICUs were introduced to protect patients, staff and visitors, in an attempt to reduce the risk of spreading the disease.15,16 In many cases only a very small number of close relatives were allowed to visit at the end of life, and often not even at that time, thus preventing the patient from being accompanied in this special context. Such restrictions caused significant distress to patients, relatives and staff.17,18

To date, there is little scientific literature analysing how the pandemic modified ICU visiting policy, information to relatives and nursing care practices at the end of life, this information being restricted to that which occurred at the beginning of the pandemic (first and second waves). Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the modifications suffered during the different waves of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Spain with respect to the policy of visits to ICU patients in general, specifically in end-of-life accompaniment, and the use of new communication technologies between relatives, patients and professionals.

Material and methodsDesign, scope and participantsA national cross-sectional survey was carried out, the project of which was endorsed after evaluation by the panel of experts comprising the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care Nursing and Coronary Units (hereinafter, SEEIUC for its initials in Spanish).

The inclusion criteria for the recruitment of ICUs as potential participants were: (a) units with an admission capacity of more than 10 beds, (b) that admitted patients aged 18 years or older (adult units), (c) units that existed prior to the pandemic and were not created for this reason, and (d) units belonging to hospitals in both the public and private health systems in Spain.

Data collection toolA questionnaire (material S1) including multiple-choice and/or open-ended questions was developed. The survey began with 11 questions relating to the characteristics of the participating unit: employment category of the respondent, type of hospital, public or private funding, belonging to a university network (university hospital), number of beds in the hospital and of the ICU in particular. Next, 21 questions were asked, organised into three sections according to the subject matter into which they can be grouped: (a) data relating to changes in visiting policy by relatives in general; (b) results concerning the evolution of routines in terms of visits by relatives in end-of-life care; (c) data referring to the use of new technologies in the communication of relatives with hospitalised patients.

These last questions were asked in 5 periods, coinciding with different times of the COVID-19 pandemic: pre-pandemic (December 2019), first wave of the pandemic (March–June 2020), second wave (September–December 2020), third wave (January–March 2021) and fourth wave (April–June 2021).

Survey distributionThe SEEIUC Secretariat sent an e-mail on 7 February 2022 to all the ICUs whose details were included in the SEEIUC Secretariat register of units at that date. This email was sent to Head Nurses, Nursing Supervisors or ICU nurses, attaching a cover letter explaining the project in summary form and its objectives. The e-mail contained a link to Google Forms that gave access to the survey. By means of successive e-mails sent by the research team, participation was encouraged and the doubts raised were resolved. Finally, on 15 April 2022, data collection was terminated. If duplicate surveys were found, the one answered by the hierarchically superior position was always taken into account.

Data analysisThe results of the present survey are reported following the guidelines of the Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS)19 document.

Data are presented as absolute number and percentage for quantitative variables, and medians with interquartile range for continuous variables. After analysis of the normality of the distributions using the Shapiro–Wilk test, the chi-square test was used for qualitative variables, with the Mann–Whitney U or Student's t-test being the tests of choice for quantitative variables as required. The aim was to compare the previously defined periods of analysis. A two-tailed p is considered statistically significant if the two-tailed p is <.05. The statistical analysis of the data was supported by the use of the specific software SPSS® version 25 (IBM corp., SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The statistical analysis was performed by the principal investigator of the project, with a re-analysis by the senior investigator.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Virgen Macarena and Virgen del Rocío University Hospitals of Seville (internal code: 1195-N-21). The ethical aspects of the study, anonymous data handling and participants' rights were detailed in the invitation letter sent to the ICUs prior to the start of data collection. All the data obtained were handled anonymously to safeguard their confidentiality, guaranteed by means of encrypted codes associated with each of the ICUs included and preventing their absolute identification. The data were kept in the custody of the principal investigator and destroyed once they were no longer required for the dissemination of the study results.

ResultsOf the 179 ICUs contacted by the above methods, a total of 57 surveys were obtained which, after elimination of duplicates, remained at 52, leaving a response rate of 29%.

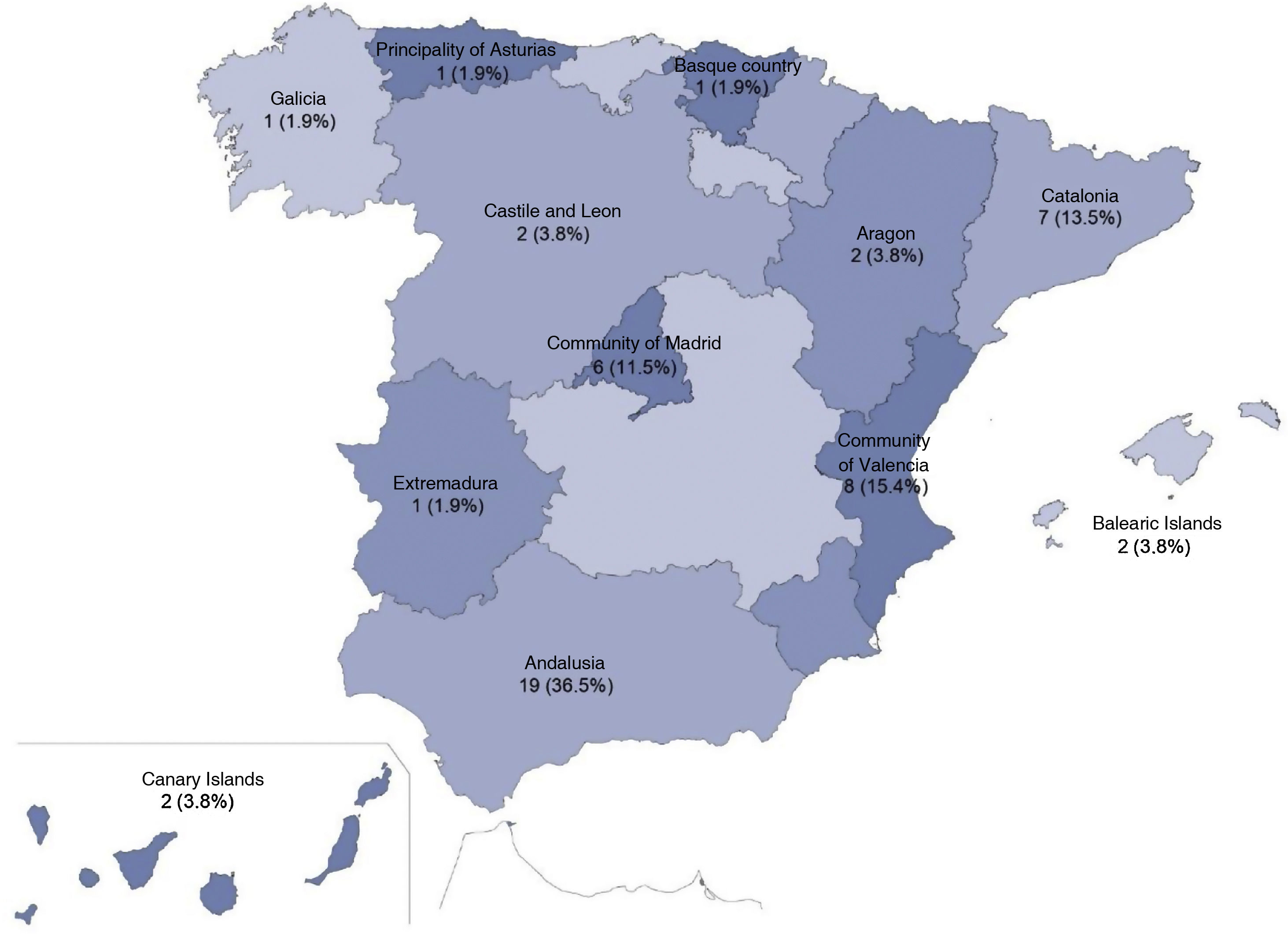

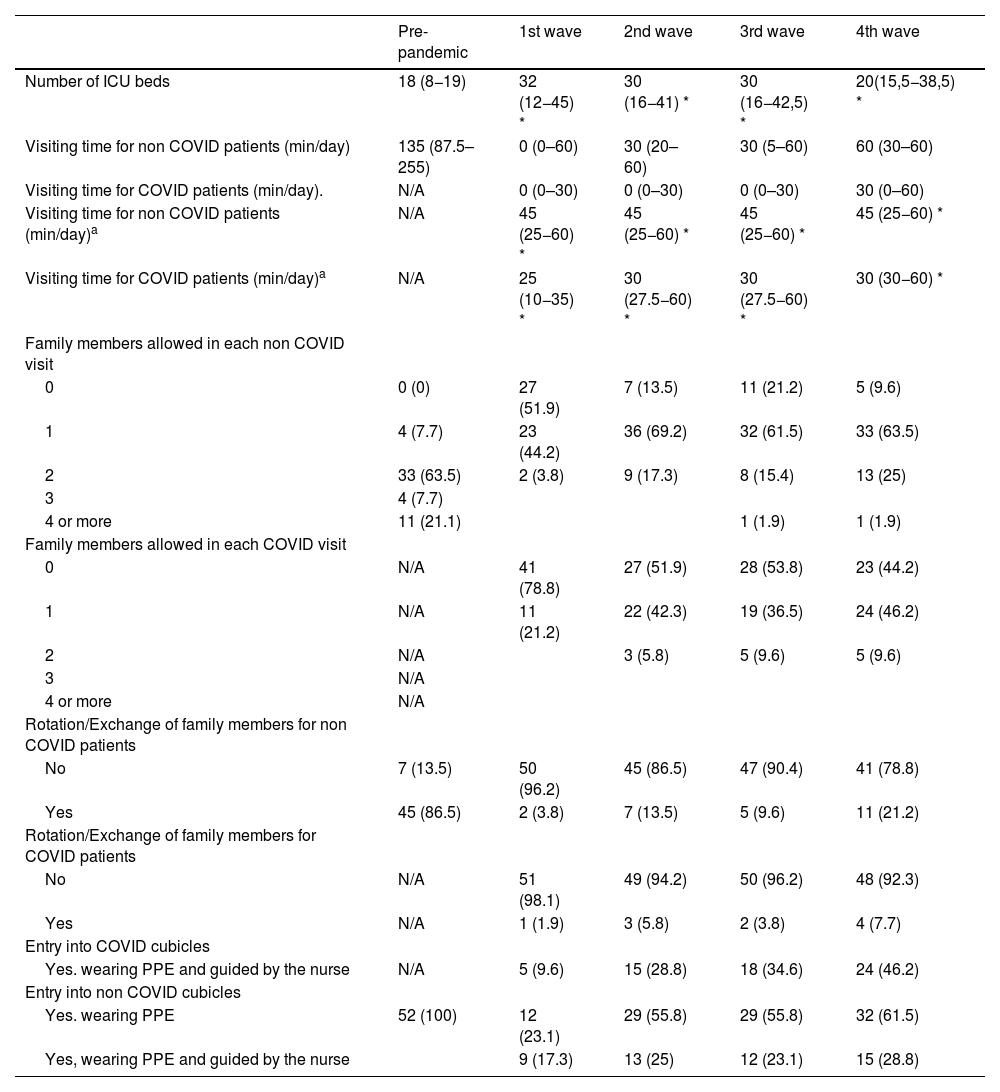

The distribution by province of the participating ICUs is shown in Fig. 1. Nursing Supervision was responsible for answering the survey on 45 occasions (86.5%), followed by ICU nurses and Care Coordination on 6 (11.5%) and 1 (1.9%) occasions respectively. The hospitals were 82.7% public and 90.4% were university hospitals. Finally, 9 (17.3%) hospitals were first level, 23 (44.2%) second level and 20 (38.5%) third level. The median number of hospital beds before the pandemic was 392.5 (210–687.5). The number of ICU beds almost doubled comparing the pre-pandemic state and the different waves with statistical significance (Table 1), with a total of 1334 beds included in the study and reaching 1664 in the wave with the most admissions.

General visiting policy during the different waves of COVID-19.

| Pre-pandemic | 1st wave | 2nd wave | 3rd wave | 4th wave | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ICU beds | 18 (8−19) | 32 (12−45) * | 30 (16−41) * | 30 (16−42,5) * | 20(15,5−38,5) * |

| Visiting time for non COVID patients (min/day) | 135 (87.5–255) | 0 (0–60) | 30 (20–60) | 30 (5–60) | 60 (30–60) |

| Visiting time for COVID patients (min/day). | N/A | 0 (0–30) | 0 (0–30) | 0 (0–30) | 30 (0–60) |

| Visiting time for non COVID patients (min/day)a | N/A | 45 (25−60) * | 45 (25−60) * | 45 (25−60) * | 45 (25−60) * |

| Visiting time for COVID patients (min/day)a | N/A | 25 (10−35) * | 30 (27.5−60) * | 30 (27.5−60) * | 30 (30−60) * |

| Family members allowed in each non COVID visit | |||||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 27 (51.9) | 7 (13.5) | 11 (21.2) | 5 (9.6) |

| 1 | 4 (7.7) | 23 (44.2) | 36 (69.2) | 32 (61.5) | 33 (63.5) |

| 2 | 33 (63.5) | 2 (3.8) | 9 (17.3) | 8 (15.4) | 13 (25) |

| 3 | 4 (7.7) | ||||

| 4 or more | 11 (21.1) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| Family members allowed in each COVID visit | |||||

| 0 | N/A | 41 (78.8) | 27 (51.9) | 28 (53.8) | 23 (44.2) |

| 1 | N/A | 11 (21.2) | 22 (42.3) | 19 (36.5) | 24 (46.2) |

| 2 | N/A | 3 (5.8) | 5 (9.6) | 5 (9.6) | |

| 3 | N/A | ||||

| 4 or more | N/A | ||||

| Rotation/Exchange of family members for non COVID patients | |||||

| No | 7 (13.5) | 50 (96.2) | 45 (86.5) | 47 (90.4) | 41 (78.8) |

| Yes | 45 (86.5) | 2 (3.8) | 7 (13.5) | 5 (9.6) | 11 (21.2) |

| Rotation/Exchange of family members for COVID patients | |||||

| No | N/A | 51 (98.1) | 49 (94.2) | 50 (96.2) | 48 (92.3) |

| Yes | N/A | 1 (1.9) | 3 (5.8) | 2 (3.8) | 4 (7.7) |

| Entry into COVID cubicles | |||||

| Yes. wearing PPE and guided by the nurse | N/A | 5 (9.6) | 15 (28.8) | 18 (34.6) | 24 (46.2) |

| Entry into non COVID cubicles | |||||

| Yes. wearing PPE | 52 (100) | 12 (23.1) | 29 (55.8) | 29 (55.8) | 32 (61.5) |

| Yes, wearing PPE and guided by the nurse | 9 (17.3) | 13 (25) | 12 (23.1) | 15 (28.8) |

Data are shown as median (P25–P75) for continuous figures and as number (percentage) for discrete figures.

ICU, Intensive Care Unit; PPE, Personal Protective Equipment.

In the pre-pandemic state, 24 of the participating units (46.2%) had an extended visiting policy. All units allowed family members to visit patients, with one ICU with only one visit per day, 20 with two visits, 18 with three, 4 with four and 9 with 5 or more visits.

In the first wave, in 41 of the Units (78.8%) family members were not allowed access to COVID-19 patients and in 27 Units (51.9%) access was not possible when the patient was admitted for a pathology other than COVID-19. The number of units that did not allow access decreased significantly in the different waves for both COVID-19 patients and patients with other pathologies as shown in Table 1. In the fourth wave (April-June 2021), 23 (44.2%) of the surveyed units did not allow access for relatives to visit patients admitted for COVID-19 and five ICUs did not allow access even for relatives of patients admitted for another pathology.

Compared to pre-pandemic visiting time, this decreased dramatically and statistically significantly from a median of 135min to 0min for COVID patients and 30min for non-COVID patients. This was gradually reversed and slightly increased again as the waves progressed, but was always more favourable in the case of non-COVID patients.

With regard to the rotation/exchange of relatives during the visit, this was allowed in 86.5% of the units, becoming possible only in one unit (1.9%) in the case of COVID-19 patients and in two units (3.8%) in non-COVID-19 patients (p<.01 both proportions with respect to pre-pandemic status. In the fourth wave, rotation/switching was allowed in 11 units (21.2%) when dealing with non-COVID-19 patients and only in four (7.7%) in the case of COVID-19 patients.

Furthermore, with regard to access to the cubicles by the family for the visit of the patient admitted for COVID-19, this was only permitted in five of the units (9.6%), this figure progressively rising to 46.2% in the fourth wave. In the case of admission for reasons other than COVID-19. These percentages were higher, with the family member having to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) in 17.3% of the units in the first wave, 25% in the second, 23.1% in the third and 28.8% in the fourth.

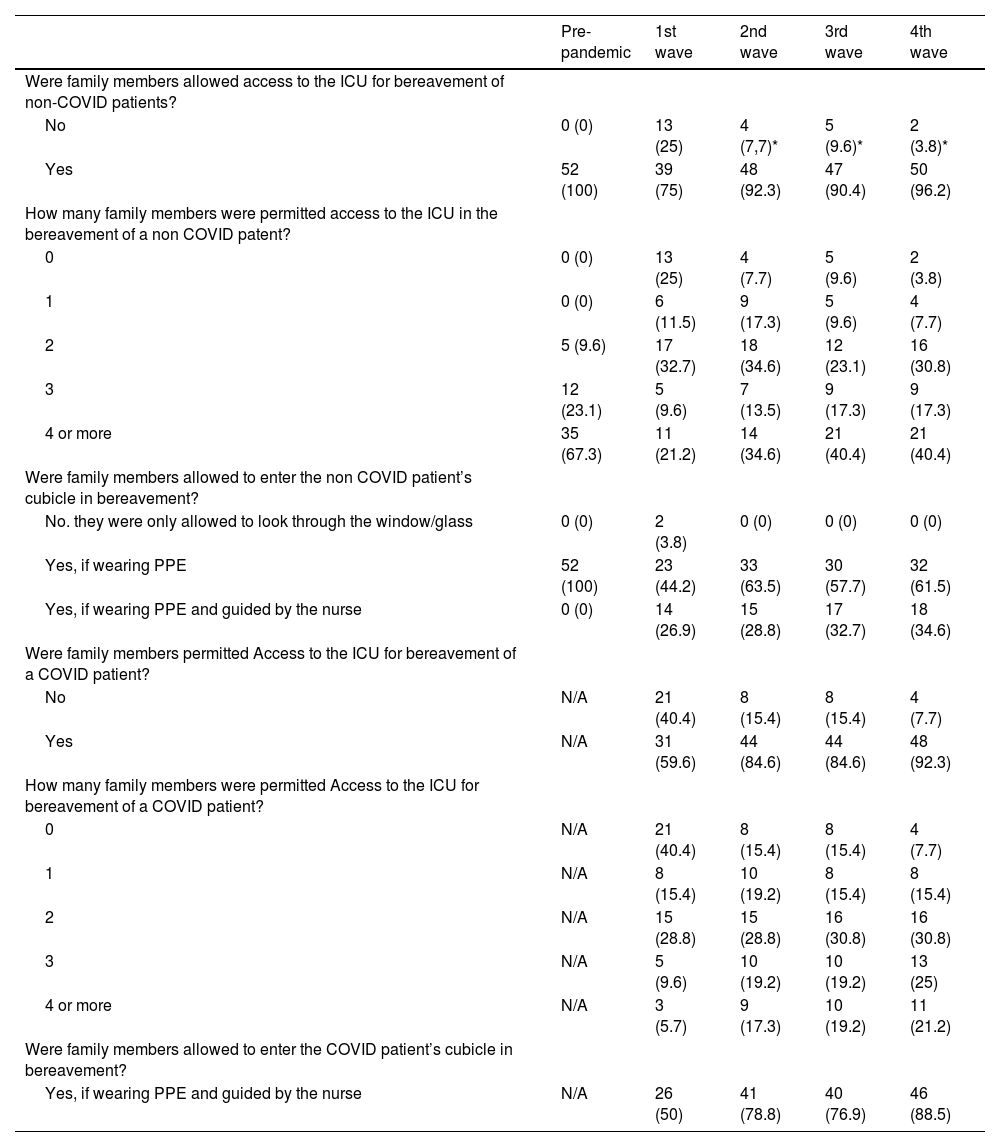

Visiting policy in situations of mourning or end-of-life stagesIn the specific case of visits and/or accompaniment of the end-of-life stage patient, prior to the pandemic, in all cases family members were allowed access to the patient's cubicle, with the presence of 4 or more people being possible in 35 hospitals out of the 52 hospitals surveyed (67.3%) at these times.

In the first wave, bereaved relatives were allowed access in the case of non-COVID patients in 75% of the units and in 59.6% of cases for COVID-19 patients (p=.09). In successive waves, as shown in Table 2, access to bereavement in case of a non-COVID-19 patient was allowed in more than 90% of the participating units (p<.05 compared to the first wave). In the case of COVID-19 patients, the percentage rose to 84.6% in the second and third waves and to 92.3% in the fourth wave (p<.05 compared to the first wave). It should be noted that, in the fourth wave, relatives were still not allowed to pass through in the case of end-of-life patients in two units for non-COVID-19 patients and in four units for COVID-19 patients.

Visiting policy for bereavement or end-of-life care.

| Pre-pandemic | 1st wave | 2nd wave | 3rd wave | 4th wave | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were family members allowed access to the ICU for bereavement of non-COVID patients? | |||||

| No | 0 (0) | 13 (25) | 4 (7,7)* | 5 (9.6)* | 2 (3.8)* |

| Yes | 52 (100) | 39 (75) | 48 (92.3) | 47 (90.4) | 50 (96.2) |

| How many family members were permitted access to the ICU in the bereavement of a non COVID patent? | |||||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 13 (25) | 4 (7.7) | 5 (9.6) | 2 (3.8) |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 6 (11.5) | 9 (17.3) | 5 (9.6) | 4 (7.7) |

| 2 | 5 (9.6) | 17 (32.7) | 18 (34.6) | 12 (23.1) | 16 (30.8) |

| 3 | 12 (23.1) | 5 (9.6) | 7 (13.5) | 9 (17.3) | 9 (17.3) |

| 4 or more | 35 (67.3) | 11 (21.2) | 14 (34.6) | 21 (40.4) | 21 (40.4) |

| Were family members allowed to enter the non COVID patient’s cubicle in bereavement? | |||||

| No. they were only allowed to look through the window/glass | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Yes, if wearing PPE | 52 (100) | 23 (44.2) | 33 (63.5) | 30 (57.7) | 32 (61.5) |

| Yes, if wearing PPE and guided by the nurse | 0 (0) | 14 (26.9) | 15 (28.8) | 17 (32.7) | 18 (34.6) |

| Were family members permitted Access to the ICU for bereavement of a COVID patient? | |||||

| No | N/A | 21 (40.4) | 8 (15.4) | 8 (15.4) | 4 (7.7) |

| Yes | N/A | 31 (59.6) | 44 (84.6) | 44 (84.6) | 48 (92.3) |

| How many family members were permitted Access to the ICU for bereavement of a COVID patient? | |||||

| 0 | N/A | 21 (40.4) | 8 (15.4) | 8 (15.4) | 4 (7.7) |

| 1 | N/A | 8 (15.4) | 10 (19.2) | 8 (15.4) | 8 (15.4) |

| 2 | N/A | 15 (28.8) | 15 (28.8) | 16 (30.8) | 16 (30.8) |

| 3 | N/A | 5 (9.6) | 10 (19.2) | 10 (19.2) | 13 (25) |

| 4 or more | N/A | 3 (5.7) | 9 (17.3) | 10 (19.2) | 11 (21.2) |

| Were family members allowed to enter the COVID patient’s cubicle in bereavement? | |||||

| Yes, if wearing PPE and guided by the nurse | N/A | 26 (50) | 41 (78.8) | 40 (76.9) | 46 (88.5) |

Data are presented as number (percentage) or median (P25–P75).

ICU, intensive care unit; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Although 31 units allowed access to relatives of COVID-19 patients in the first wave, only 26 allowed access to the inside of the cubicle. In the case of non-COVID-19 patients, 37 out of 39 units allowed access to the interior.

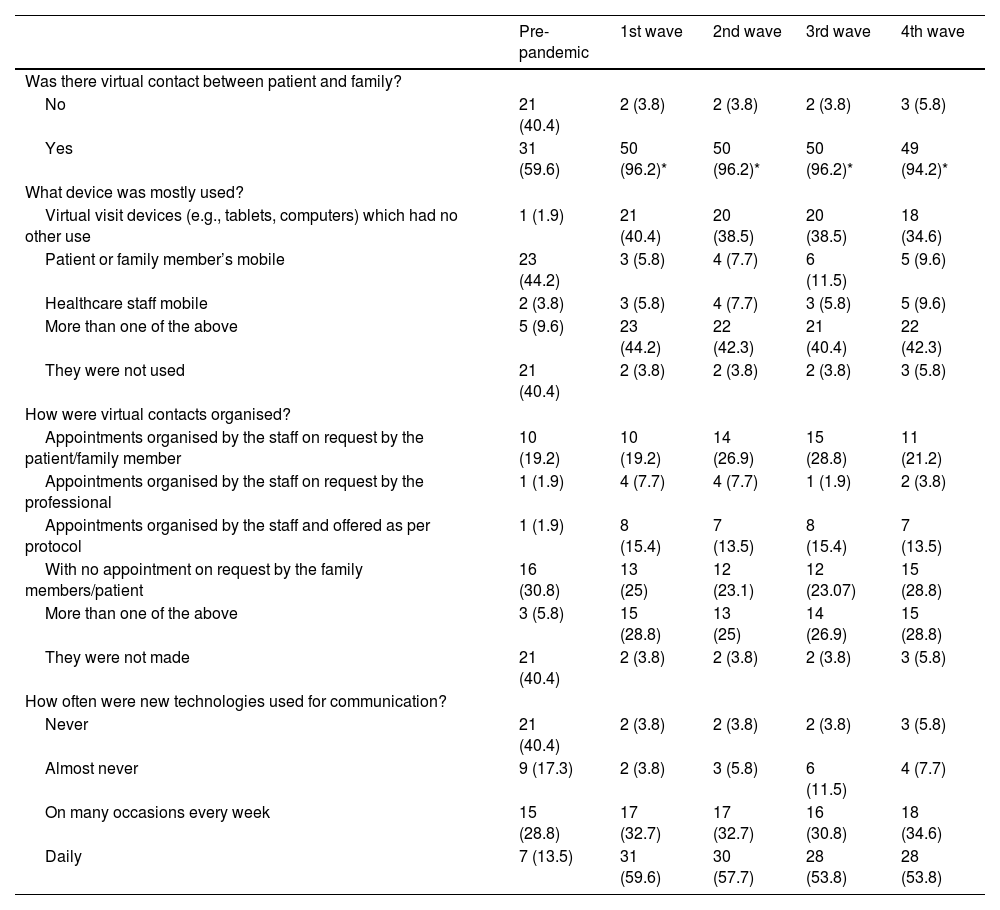

Communication with family members and use of new technologiesTable 3 shows the data relating to the information provided to relatives on the condition of patients, as well as the form of communication and the use of new technologies in this respect. The number of times relatives are contacted by healthcare staff does not vary across the waves, being only once in 88.4% of the hospitals surveyed.

New technology usage routines.

| Pre-pandemic | 1st wave | 2nd wave | 3rd wave | 4th wave | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was there virtual contact between patient and family? | |||||

| No | 21 (40.4) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.8) |

| Yes | 31 (59.6) | 50 (96.2)* | 50 (96.2)* | 50 (96.2)* | 49 (94.2)* |

| What device was mostly used? | |||||

| Virtual visit devices (e.g., tablets, computers) which had no other use | 1 (1.9) | 21 (40.4) | 20 (38.5) | 20 (38.5) | 18 (34.6) |

| Patient or family member’s mobile | 23 (44.2) | 3 (5.8) | 4 (7.7) | 6 (11.5) | 5 (9.6) |

| Healthcare staff mobile | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.8) | 4 (7.7) | 3 (5.8) | 5 (9.6) |

| More than one of the above | 5 (9.6) | 23 (44.2) | 22 (42.3) | 21 (40.4) | 22 (42.3) |

| They were not used | 21 (40.4) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.8) |

| How were virtual contacts organised? | |||||

| Appointments organised by the staff on request by the patient/family member | 10 (19.2) | 10 (19.2) | 14 (26.9) | 15 (28.8) | 11 (21.2) |

| Appointments organised by the staff on request by the professional | 1 (1.9) | 4 (7.7) | 4 (7.7) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.8) |

| Appointments organised by the staff and offered as per protocol | 1 (1.9) | 8 (15.4) | 7 (13.5) | 8 (15.4) | 7 (13.5) |

| With no appointment on request by the family members/patient | 16 (30.8) | 13 (25) | 12 (23.1) | 12 (23.07) | 15 (28.8) |

| More than one of the above | 3 (5.8) | 15 (28.8) | 13 (25) | 14 (26.9) | 15 (28.8) |

| They were not made | 21 (40.4) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.8) |

| How often were new technologies used for communication? | |||||

| Never | 21 (40.4) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.8) |

| Almost never | 9 (17.3) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.8) | 6 (11.5) | 4 (7.7) |

| On many occasions every week | 15 (28.8) | 17 (32.7) | 17 (32.7) | 16 (30.8) | 18 (34.6) |

| Daily | 7 (13.5) | 31 (59.6) | 30 (57.7) | 28 (53.8) | 28 (53.8) |

Data is presented as a number (percentage).

The use of new technologies increased significantly with the pandemic, from 59.6% of units before the pandemic to 96.2% in the first, second and third waves (p<.001). Likewise, mobile phones of relatives/patients were preferentially used in the pre-pandemic state, and 20% of the time during the pandemic other devices were used exclusively for this purpose, or a combination of both. There were no changes in the organisation of contacts, where staff-arranged appointments at the request of the relative/patient or without prior appointment prevailed. The use of virtual contacts between patients and relatives increased significantly compared to the pre-pandemic, with the percentages of use remaining stable throughout the four waves (Table 3).

DiscussionOur study shows that during the first wave of the pandemic caused by SARS-COV-2, visits were substantially restricted, both to patients admitted for COVID-19 and to those admitted for other reasons. It should be pointed out that, although this trend was reduced, in the fourth wave the situation had not yet returned to the previous one, and in some units it was not possible for relatives to have access even to patients admitted for non-COVID pathology.

The humanisation of healthcare is even more important when dealing with critically ill patients.20 Restricting visits to COVID and non-COVID patients has been a widespread practice worldwide.21 However, according to our data, Spain was less restrictive than other countries, with 84% of ICUs worldwide prohibiting access in the first wave (66% in the case of non-COVID patients)22 or 96% in the case of Italian ICUs.23 In the UK, on the other hand, access to any external person was denied in only 22% of ICUs,24 with Scandinavia being even more liberal, with only 7% total prohibition.25

This restriction on visits was in line with the Contingency Plan drawn up by SEEIUC and SEMICYUC, which recommended reducing the accompaniment of patients to the minimum necessary, whether or not they had COVID-19 disease, due to the high risk of infection for the entire population during the first wave of the pandemic and the shortage of PPEs.16 However, soon, various scientific societies and opinion leaders issued documents urging the "re-opening" of ICUs to relatives and allowing patients to be accompanied.14,26,27

Although this limiting trend was reduced in successive waves, one and a half years after the start of the pandemic, five units still did not allow access for relatives to visit non-COVID patients and as many as 23 did not allow access to the unit to visit COVID patients. In addition to this, we found that the exchange of relatives, which was allowed before the pandemic in more than 85% of the participating units, was only allowed in the fourth wave in 7.7% for COVID-19 patients and in 21% when the patient had been admitted for a different pathology. Shortage of PPE was a reason for restriction of visits in the first wave, which could not be argued as a reason in the following waves where there was no such shortage of equipment. In the survey by Langer et al. (2022), it was described how 63% of the units only allowed access to a single family member with no possibility of rotation.23 This contrasts with published evidence that visiting the ICU during the pandemic reduced the anxiety of relatives of admitted patients.28 Similarly, the opening of the ICUs did not lead to an increase in COVID-19 infections, neither among healthcare staff nor among relatives who participated in patient visits.29 In addition, family visits were associated during the first wave with a lower risk of admission-associated delirium.30 In fact, other studies indicate that access by several relatives (at the same time or individually) is necessary and, if this is not possible, priority should be given to those who benefit most from the visit.31 Moreover, in certain contexts it was observed that assigning a responsible relative caused great stress to the relative and to the rest of the family, with rotation among several people therefore being recommended.32

With regard to the end-of-life care, the pandemic also had a major impact on visiting times and access to ICUs themselves. All this resulted in nurses not being able to provide good care in stages of need or at the end of life,33 increasing the workload by having to "reinvent" the way of providing care to the family during bereavement.34 Thus, in the first wave, 40% of units did not allow access in COVID bereavement, a situation that was reversed in subsequent waves. In the UK, this occurred in 47% of cases, with a maximum visit duration of 15min.24 In the multi-centre survey by Tabah et al. (2022), restrictions were shown to be much more liberal in this context, with 67% of ICUs surveyed citing the patient's terminal condition as a reason for overriding the visit restriction.22 In Denmark and Norway, bans occurred in up to 40% of units despite the patient's poor condition, and in Sweden, bereaved relatives were only allowed access in 70% of cases, a decision taken between the doctor and the nurse.25

To alleviate this problem, Xu et al. (2022) recommended allowing the necessary time to the bereaved family, stressing that the lack of family members in this context is a barrier to nursing care.35 In fact, nurses have had to adopt the role of family members in certain palliative contexts,36 using new communication technologies to try to reduce their stress.37

Finally, regarding virtual contacts, their implementation increased with the restriction of visits to 96.2%, favouring the use of dedicated electronic devices managed by healthcare staff. This percentage was lower according to the COVISIT study worldwide, with 63% availability on average in the 14 countries surveyed. However, we agree on the protocolisation of contacts, which in both cases was 14%.22 In 40% of the units, dedicated devices such as tablets or computers were used for virtual contacts, while in a study in Canada, cameras installed in the cubicles were used,38 with a nurse responsible for carrying out the videoconferences.39 Virtual contacts went from never or rarely made in a pre-pandemic state, to daily or often weekly in more than 80% of cases. During the pandemic, video calls were seen as a window to the patient's home,40,41 but required technical and emotional preparation on the part of family and healthcare staff that often led to problems in care.42 In the UK, many relatives were certainly concerned, as they did not want to be disturbed by calling, and adapted, accessible and flexible family visiting strategies were needed.43 On the other hand, the study by Zante et al. (2022) shows that, in Switzerland, the policy of virtual visits did not reduce the appearance of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in the relatives of hospitalised patients, so that in no case can the use of new communication technologies be considered an absolute substitute for face-to-face visits.44

The main limitation of our study lies in the relatively low response rate on the part of the ICUs contacted, although they were mostly units with a high number of beds and therefore admissions. It may also have been the case that those units more sensitive to the humanisation of care in the pandemic responded. We were also unable to make comparisons between hospitals according to type of financing, given the low response rate to the survey. As a strength, it should be noted that so far there is no published information on how the pandemic modified the key aspects of the humanisation of care and how it evolved in the successive waves in Spain.

ConclusionsThe families of patients admitted to the ICU during the different waves of the COVID-19 pandemic have seen their rights diminished, with restrictions on visits and a change from face-to-face visits to virtual communication techniques. Despite the solutions implemented and the virtual communication, efforts should be directed towards improving the protocols for the humanisation of health care, allowing care for relatives and patients whatever the health care context, favouring their visits, encouraging accompaniment in bereavement situations and attending to the mental health of the professionals involved.

FundingThis research study has not received specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the results of the submitted manuscript.

To all the nurses in Spanish intensive care units who have dedicated their time to completing the survey and, in particular, to the Sociedad Española de Enfermería Intensiva y Unidades Coronarias (Spanish Society of Intensive Care Nursing and Coronary Units) for endorsing this project and disseminating it appropriately.