Nursing professionals working in Intensive Care Units (ICU) are at high risk of developing negative emotional responses as well as emotional and spiritual problems related to ethical issues. The design of effective strategies that improve these aspects is determined by knowing the levels of burnout and ethical conflict of these professionals, as well as the influence that the practice environment might have on them.

ObjectivesTo analyze the relationship between levels of burnout, the exposure to ethical conflicts and the perception of the practice environment among themselves and with sociodemographic variables of the different intensive care nursing professionals.

MethodsDescriptive, correlational, cross-sectional, observational study in an ICU of a tertiary level university hospital. The level of burnout was evaluated with the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey scale; the level of ethical conflict with the Ethical Conflict Questionnaire for Nurses and the perception of the environment with the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index. Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed. The association between categorical variables was analyzed using Fisher’s exact chi-square test (χ2)

Results31 nurses and 8 nursing assistants were evaluated, which meant a participation rate of 82,93%. 31,10% of the nursing professionals presented signs of burnout, 14,89% considered that they work in an unfavorable environment and 87,23% presented a medium-high index of exposure to ethical conflict.

The educational level (χ2=11.084, p=0.011) and the professional category (χ2=5.007, p=0.025) influenced the level of burnout: nursing assistants presented higher levels of this.

When comparing the level of burnout with the environment and the index of ethical conflict, there were no statistically significant differences.

ConclusionsThe absence of association found in the study between Burnout and ethical conflict with the perception of the practice environment suggests that personal factors may influence its development.

Los profesionales de enfermería que trabajan en Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) poseen un alto riesgo de desarrollar respuestas emocionales negativas, así como problemas emocionales y espirituales relacionados con cuestiones éticas. El diseño de estrategias efectivas que mejoren estos aspectos viene determinado por el conocimiento de los niveles de burnout y conflicto ético de dichos profesionales, así como la influencia que el entorno de la práctica puede tener en ellos.

ObjetivoAnalizar la relación existente entre niveles de burnout, exposición a conflicto ético y la percepción del ambiente de la práctica entre sí y con las variables sociodemográficas de los diferentes profesionales de enfermería de cuidados intensivos.

MetodologíaEstudio transversal correlacional en una UCI de un hospital universitario de nivel terciario. Se evaluó el nivel de burnout con la escala Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human-Services Survey; el nivel de conflicto ético con el cuestionario de conflictividad ética para enfermeros y la percepción del entorno con la escala Practice-Environment-Scale of the Nursing-Work-Index. La asociación entre variables categóricas ha sido analizada mediante el test exacto de Fisher de chi-cuadrado(χ2).

ResultadosSe evaluaron 39 enfermeras y 8 auxiliares, obteniendo una tasa de participación del 82,93%. El 31,10% de los profesionales de enfermería presentaron signos de burnout, el 14,89% consideraron que trabaja en un entorno desfavorable y el 87,23% presentaron un índice de exposición a conflicto ético medio-alto.

El nivel educativo (χ2=11,084, p=0,011) y la categoría profesional (χ2=5,007, p=0,025) influyeron en el nivel de burnout, presentando las auxiliares mayores niveles del mismo.

Al comparar el nivel de burnout con el entorno y el índice de conflicto ético no hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas.

ConclusionesLa ausencia de asociación encontrada en el estudio entre Burnout y conflicto ético con la percepción del entorno de la práctica hace pensar que los factores personales pueden influir en su desarrollo.

What is known?

- •

Intensive care units are stressful and demanding environments where patients are admitted with life-threatening conditions and where nurses and nursing. assistants may develop burnout syndrome and become highly exposed to ethical conflict.

- •

Previous research has shown associations between burnout, ethical conflict, and the perception of the practice environment.

What it contributes?

- •

The lack of an association in this study between burnout, conflict, and the perception of the practice environment suggests that there are other factors that may influence the development of burnout.

- •

We identify the situations that trigger the greatest ethical conflict and relate the degree of ethical conflict to moral state.

Study implications

Establishing the level of burnout, the perception of the environment, and the situations that trigger ethical conflict in our nurses, and the relationship between these factors, will help deepen our understanding of their importance and design specific interventions aimed at specific professionals and scenarios. These interventions should take individual factors into account.

Intensive care units (ICU) are complex and dynamic areas, defined as highly stressful and demanding, contextualised in a volatile setting,1 determined by a high level of technification, and requiring the continuous education and training of healthcare professionals.2–4

The daily practice of intensive care professionals as a whole becomes challenging in an setting characterised by work stressors: high workloads, high risk of developing negative emotional responses related to death (ICU is the area with the highest mortality rate [16%–20%]5), and the suffering of critically ill patients, moral and spiritual problems related to ethical issues.1,6,7 In the specific case of nurses, constant proximity to the patient can add an emotional burden to the situations they experience.6 This can lead to feelings of anxiety, depression, disillusionment, a desire to give up, disinterest, and reduced job satisfaction,3,6,8 resulting in observable burnout syndrome3 and exposure to ethical conflict.6,8

Maslach, in 1978, described burnout as chronic stress produced by contact with patients, leading to exhaustion and emotional distancing at work.9 This phenomenon is a response to chronic interpersonal stressors, where the dominant symptoms are characterised by emotional exhaustion (feelings of being emotionally drained and overextended in terms of emotional resources), depersonalisation (negative, cynical, and impersonal attitudes, generating distant feelings towards other people), and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of self-fulfilment (diminished feelings of competence and success at work, and a tendency to negative self-evaluation).3

It is important to note that burnout has a relatively high prevalence in the nursing profession, with a considerable incidence in intensive care units.7,10 It is estimated that between 23% and 43% of ICU nurses worldwide suffer from the syndrome.11

The concept of ethical conflict has been defined as a phenomenon that arises when one knows the ethically correct action to take, but is constrained from acting.12 It is a problem that arises within and between individuals, involving the individual's scale of values and ethical principles, sense of responsibility, and ethical sensitivity.13 Generally, ethical conflicts in nursing have been studied in terms of temporal frequency and degree of conflict.2,8,14 The term index of exposure to ethical conflict has been adopted recently, which relates frequency and degree, and determines moral state.13,15–18

Both situations (ethical conflict and burnout) contribute to inadequate care, influence the prevalence of negligence, the number of complications in care,19 reduced patient safety,20,21 and can lead to nurses leaving their jobs.22

The literature shows that when professionals perceive a favourable environment and participate in decision-making, they are less exposed to ethical conflict.16,23 This participation is key as it affects their perception of the environment and level of exposure to ethical conflict,24 which is aggravated if there is a lack of support from leaders in mediating this moral distress.23

The COVID-19 pandemic increased this physical and mental exhaustion and burnout in healthcare professionals,6,25 impaired the working environment,6 and may also have affected the level of exposure to ethical conflict.8,12 Based on the initial hypothesis of the association between burnout, ethical conflict, and work environment, we propose the following objectives for this study: (1) to describe the levels of burnout and the perception of the practice environment of the different intensive care nursing professionals, and their level of exposure to ethical conflict, and (2) to analyse the relationship of each construct with the sociodemographic variables, and the relationship between them.

MethodologyAn observational cross-sectional descriptive study conducted in a 12-bed multipurpose ICU of a 300-bed tertiary level private university hospital. Between 800 and 1,000 patients are admitted annually to this unit, around 80% of whom are surgical. The remaining 20% are medical patients, multi-pathological, and/or in need of advanced therapies.

SubjectsAll nursing professionals (nurses and auxiliary nurses) were invited to participate who met the following inclusion criteria: they had been working in the unit for at least 1year and were not on sick leave or leave of absence.

All the professionals were western women who had passed the same selection process to enter the unit. Although the current trend is changing, the standard profile of nursing positions in our centre has been female. Registered nurses have intensive care training that includes a postgraduate academic programme with specific ICU content, and a 12-month practical programme in the critical care area. The team of auxiliary nurses has an intermediate level qualification.

Convenience sampling was used to select the sample.

Data collection instrumentsAll the questionnaires were self-administered. The research team prepared a document consisting of four sections:

- 1

Sociodemographic data sheet, which included profession, sex, age, academic training, years of professional experience, working hours, training in palliative care.

- 2

Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) translated and validated in Spanish.26 This questionnaire assesses burnout syndrome in health professionals. It consists of 22 items divided into 3 subscales: emotional exhaustion (9 items), depersonalisation (5 items), and personal fulfilment (8 items). The questionnaire is answered on a 7-point Likert-type response scale (from 0 "never" to 6 "daily"). High scores on emotional exhaustion (≥17) and/or depersonalisation (≥10) and/or low scores on personal fulfilment (≤33) indicate the presence of burnout syndrome. Regarding the reliability of the MBI-HSS, Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranging from .72 to .90 were obtained for each subscale, in the Spanish adaptation.26

- 3

We used the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) translated and validated in Spanish.27 This questionnaire comprises 32 items in 5 subscales: participation in hospital affairs (8 items), nursing foundations for quality of care (9 items), ability, leadership and support of supervisor (4 items), staffing and resources (4 items), and relationship between nurses and doctors (7 items). The questionnaire is answered on a 4-point Likert-type response scale (from 1 "strongly disagree" to 4 "strongly agree"). A mean score higher than 2.5 indicates that nurses tend to agree with the presence of this factor in their work environment. Therefore, the unit’s environment will be good or favourable if it has 4 or 5 factors with a mean score higher than 2.5, mixed if it has 2 or 3, and poor or unfavourable if it has 1 or no factors without that score.28 The overall content validity of the instrument according to Content Validity Indexing (CVI) is .82.27 The mean modified kappa coefficient of the items was .80, a rating of "excellent".27

- 4

Ethical Conflict Nursing Questionnaire–Critical Care (ECNQ-CCV).17 The questionnaire was designed to analyse ethical conflict in intensive care nursing arising from 19 scenarios that are potential sources of conflict. It assesses the following variables: 1)"frequency with which ethically conflictive situations emerge"; 2)"degree of ethical conflict experienced"; 3)"type of ethical conflict", with six categories (moral indifference, moral well-being, moral uncertainty, moral dilemma, moral distress, moral outrage), and 4)"exposure to ethical conflict", which arises as the product of the variables "frequency…" and "degree of ethical conflict…". We defined low (mean – 1 SD) and high (mean + 1 SD) exposure to ethical conflict, and moderate exposure as the interval between the above values, as in previous studies.15,18 The Cronbach’s Alpha of the scale was .88.17

The research team collected data from December 2020 to January 2021 with the nursing professionals who voluntarily agreed to participate. The objective and importance of the study was explained, and their participation was requested. After their consent, a member of the research team explained how to fill in the questionnaires and collected the completed questionnaires.

Data collectionWe used descriptive and inferential statistics. Qualitative or categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, and quantitative variables as the mean and standard deviation of the mean. The association between categorical variables was analysed using Fisher's exact chi-square test (χ2). We used IBM SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., 2003) for the statistical analysis. A p-value <.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Ethical considerationsApproval was obtained from the hospital's ethics committee and the centre's management to conduct the study. All participants were guaranteed anonymity, complete confidentiality of the data, and that the questionnaires would be destroyed at the end of the research (Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights). The participants gave their written consent.

ResultsOf the 44 nurses and 12 nursing assistants working in the unit over the study period, 39 nurses and 8 nursing assistants completed the surveys, resulting in a participation rate of 83.92%.

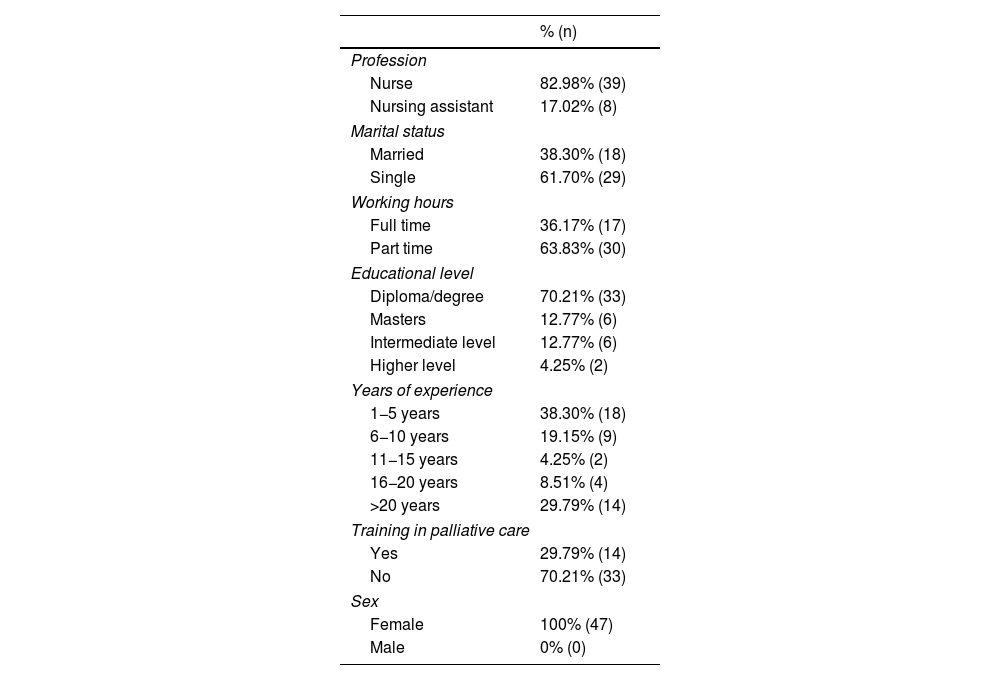

The socio-demographic data of the sample are shown in Table 1. Of the sample, 38.30% had less than 5 years’ experience working in the ICU and 29.79% more than 20 years’ experience. Of the respondents, 70.21% had a diploma/graduate degree and 70.21% had no training in palliative care.

Sociodemographic variables.

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Profession | |

| Nurse | 82.98% (39) |

| Nursing assistant | 17.02% (8) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 38.30% (18) |

| Single | 61.70% (29) |

| Working hours | |

| Full time | 36.17% (17) |

| Part time | 63.83% (30) |

| Educational level | |

| Diploma/degree | 70.21% (33) |

| Masters | 12.77% (6) |

| Intermediate level | 12.77% (6) |

| Higher level | 4.25% (2) |

| Years of experience | |

| 1−5 years | 38.30% (18) |

| 6−10 years | 19.15% (9) |

| 11−15 years | 4.25% (2) |

| 16−20 years | 8.51% (4) |

| >20 years | 29.79% (14) |

| Training in palliative care | |

| Yes | 29.79% (14) |

| No | 70.21% (33) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 100% (47) |

| Male | 0% (0) |

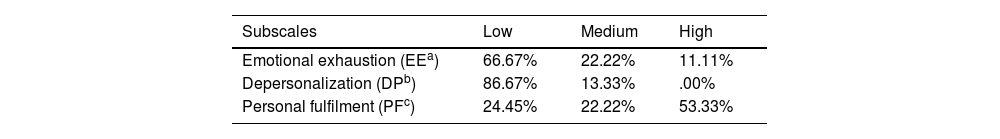

Of the sample, 31.10% showed burnout. The level reached in the subscales is presented in Table 2. Two subjects were lost for analysis of this variable, with a sample size of 45.

The factors that significantly influenced the level of burnout were educational level and profession (χ2=11.084, p=.011, and (χ2=8.745, p=.003, respectively). The nursing professionals with less academic training had higher levels of burnout with a higher level of depersonalisation (χ2=8.570, p=.036) and a lower level of personal fulfilment ((χ2=13.664, p=.034). However, the nursing assistants had higher levels of burnout than the nurses, and higher levels of depersonalisation (χ2=4.917, p=.027).

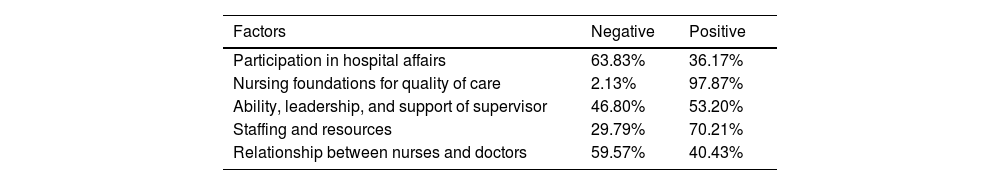

In relation to the environment, 38.30% reported a favourable environment and 14.89% an unfavourable one. Perception of the different factors that influence the environment is shown in Table 3.

Perception of environmental factors.

| Factors | Negative | Positive |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in hospital affairs | 63.83% | 36.17% |

| Nursing foundations for quality of care | 2.13% | 97.87% |

| Ability, leadership, and support of supervisor | 46.80% | 53.20% |

| Staffing and resources | 29.79% | 70.21% |

| Relationship between nurses and doctors | 59.57% | 40.43% |

Analysis of the environment with the socio-demographic data, shows no statistically significant differences in the overall scores. However, an association was found between one of the factors and profession: 62.50% of the nursing assistants perceive an unfavourable provision of resources compared to 23.07% of the nurses (χ2=4.933, p=.026).

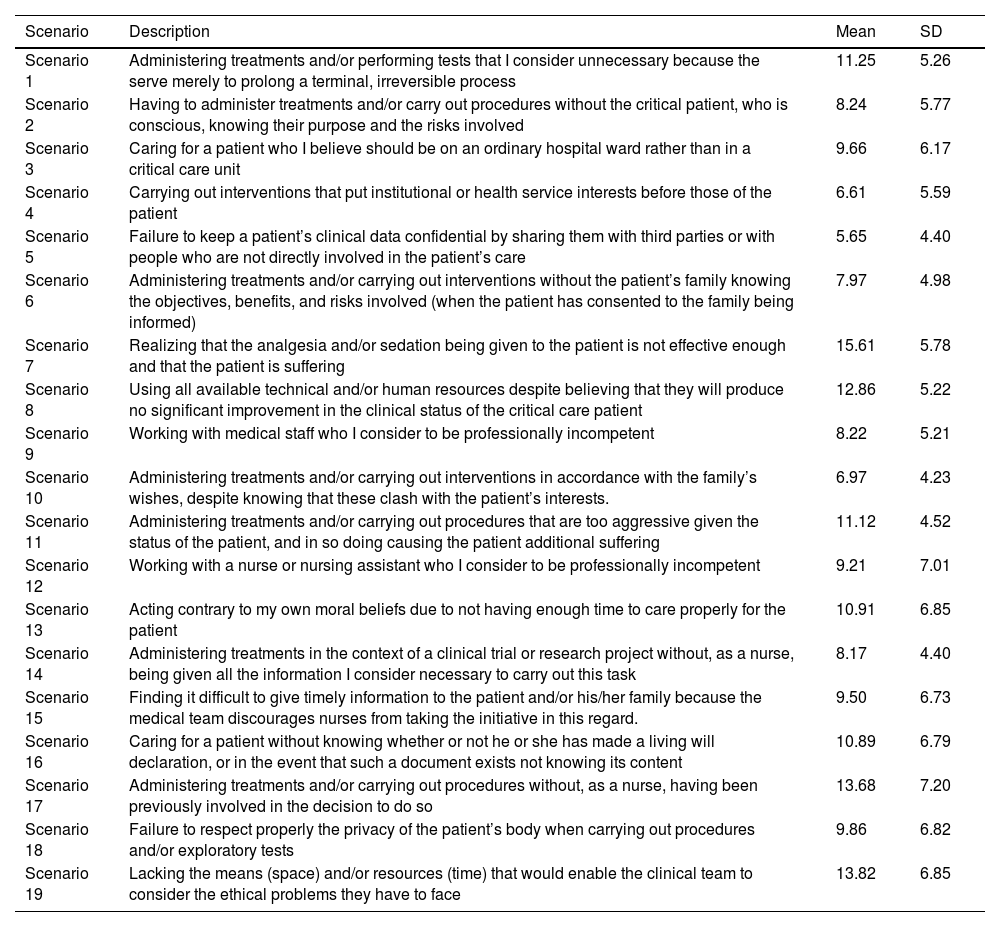

The mean level of exposure to ethical conflict was 157.44 (SD: 67.95), with a high level of exposure in 17.02% of the nursing professionals, moderate in 70.21%, and low in 12.77%. Scenario 7 triggered the highest level of ethical conflict, "Realizing that the analgesia and/or sedation being given to the patient is not effective enough and that the patient is suffering" (Table 4). In relation to moral states, moral outrage appeared in 35.15% of the professionals; moral distress in 26.33%; moral dilemma in 14.29%; uncertainty in 11.62%; well-being in 7.42%; and indifference in 5.18%.

Index of exposure to ethical conflict: Scenarios and scores.

| Scenario | Description | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | Administering treatments and/or performing tests that I consider unnecessary because the serve merely to prolong a terminal, irreversible process | 11.25 | 5.26 |

| Scenario 2 | Having to administer treatments and/or carry out procedures without the critical patient, who is conscious, knowing their purpose and the risks involved | 8.24 | 5.77 |

| Scenario 3 | Caring for a patient who I believe should be on an ordinary hospital ward rather than in a critical care unit | 9.66 | 6.17 |

| Scenario 4 | Carrying out interventions that put institutional or health service interests before those of the patient | 6.61 | 5.59 |

| Scenario 5 | Failure to keep a patient’s clinical data confidential by sharing them with third parties or with people who are not directly involved in the patient’s care | 5.65 | 4.40 |

| Scenario 6 | Administering treatments and/or carrying out interventions without the patient’s family knowing the objectives, benefits, and risks involved (when the patient has consented to the family being informed) | 7.97 | 4.98 |

| Scenario 7 | Realizing that the analgesia and/or sedation being given to the patient is not effective enough and that the patient is suffering | 15.61 | 5.78 |

| Scenario 8 | Using all available technical and/or human resources despite believing that they will produce no significant improvement in the clinical status of the critical care patient | 12.86 | 5.22 |

| Scenario 9 | Working with medical staff who I consider to be professionally incompetent | 8.22 | 5.21 |

| Scenario 10 | Administering treatments and/or carrying out interventions in accordance with the family’s wishes, despite knowing that these clash with the patient’s interests. | 6.97 | 4.23 |

| Scenario 11 | Administering treatments and/or carrying out procedures that are too aggressive given the status of the patient, and in so doing causing the patient additional suffering | 11.12 | 4.52 |

| Scenario 12 | Working with a nurse or nursing assistant who I consider to be professionally incompetent | 9.21 | 7.01 |

| Scenario 13 | Acting contrary to my own moral beliefs due to not having enough time to care properly for the patient | 10.91 | 6.85 |

| Scenario 14 | Administering treatments in the context of a clinical trial or research project without, as a nurse, being given all the information I consider necessary to carry out this task | 8.17 | 4.40 |

| Scenario 15 | Finding it difficult to give timely information to the patient and/or his/her family because the medical team discourages nurses from taking the initiative in this regard. | 9.50 | 6.73 |

| Scenario 16 | Caring for a patient without knowing whether or not he or she has made a living will declaration, or in the event that such a document exists not knowing its content | 10.89 | 6.79 |

| Scenario 17 | Administering treatments and/or carrying out procedures without, as a nurse, having been previously involved in the decision to do so | 13.68 | 7.20 |

| Scenario 18 | Failure to respect properly the privacy of the patient’s body when carrying out procedures and/or exploratory tests | 9.86 | 6.82 |

| Scenario 19 | Lacking the means (space) and/or resources (time) that would enable the clinical team to consider the ethical problems they have to face | 13.82 | 6.85 |

Statistically significant differences were found (χ2=76.062, p<.001) when relating moral state to the degree of ethical conflict. The nursing professionals with moral outrage experienced the highest degree of ethical conflict (51.07%).

Relating the index of exposure to ethical conflict (IEEC) with the sociodemographic variables, there were only statistically significant differences in palliative care training: 35.72% of the nursing professionals trained in palliative care presented a high IEEC and none a low IEEC, compared to 9.37% and 18.75%, respectively, of those who had not received training (χ2=6.591, p=.037).

When comparing the level of burnout with environment and the IEEC there were no statistically significant differences (burnout-environment [χ2=.042, p=.979]; burnout-IEEC [χ2=1.153, p=.562]; environment-IEEC [χ2=3.493, p=.479]).

DiscussionIn the literature reviewed, the level of burnout in ICU professionals is highly variable, with figures ranging from 10% to 80%,1,14,25,29–33 ranging from 31% to 68% pre-pandemic29–33 and 51%–55% in post-pandemic investigations.14,25 The present study shows that 31.10% of nursing professionals have burnout, a figure that is similar to that found by different authors29–31 and which differs from other studies.1,14,25,29,32,33 The higher levels found in other studies14,25,29,33 may be explained by the nurse/patient ratio, which is notably higher than in the hospital under study (1/1–2),33 or by exposure to unfavourable environments.29,34 The relationship between the patient/nurse ratio and mortality, adverse events, infections, costs and quality of care, and the deterioration in the quality of the working environment have been described as predisposing factors for burnout.35 Analysis of the subscales highlights that no one in the present study has high levels of depersonalisation, in contrast to that reviewed in the literature, with a range from 6% to 61%.29,31,32,36 This may be because the development of nursing professionals is contemplated both in terms of competence and at the human level within the values promoted by the institution where the study was conducted.37

Although no statistically significant differences were found between burnout and years of work experience, it was observed that nurses and nursing assistants with a longer professional career had a higher level of burnout. This relationship should be viewed with caution, as there is controversy in the literature reviewed.3,7,29,32 However, newer people may be more sensitive to burnout because they are learning to cope with high work demands and their working conditions are worse.10 On the other hand, years of ICU work experience are directly associated with nurses' moral distress, because they may suffer cumulative distress,24 which influences burnout levels.8

As for the educational level of staff, there is an association between educational level and burnout, as in previous research.29,32 Professionals with a lower level of education have higher levels of burnout. This could be because the less educated the professionals, the less autonomous they are.21,29

Because we found no association in most of the variables studied, both in the overall assessment of burnout and in its different subscales, we believe that personality factors of the nursing professionals29 may influence the level of burnout.

In the present study, the perception of the environment was unfavourable in only 14.89% of the respondents, in contrast to the study by Fuentelsaz-Gallego et al.,34 who described 48.20%. When observing the different factors of the environment scale, it is striking that 97.87% of the professionals perceive the "Nursing foundations for quality of care" as positive, in contrast to the literature reviewed.34 This may be because in our unit there has always been a concern for holistic patient care38,39 and we have developed a person-centred care model as defined by the institution.40

An association was only found in terms of profession and provision of resources, where more than half the nursing assistants perceive unfavourable provision of resources. This may be because, although the nursing assistant/patient ratio is in line with that recommended by the ministry, in other words, 1 nursing assistant for every 4 patients on day shifts and 1 for every 6 patients on night shifts,41 it may be insufficient when the severity of the patient is considered. However, the scarcity of literature exploring the perceptions of nursing assistants in relation to the environment should be highlighted.

Of the participants, 59.6% perceive the "Relationship between nursing and medicine" as unfavourable. Although all the nursing professionals recognise the importance of communication and multidisciplinary work, daily practice is still hierarchical and they do not feel they are on an equal footing to participate in decision-making.8,42 Several studies have shown that some conflict scenarios arise from inter-professional relationships and team dynamics, resource management, or burnout,15,16 and that the more deteriorated the environment, the higher the levels of ethical conflict among nursing professionals.43

The level of exposure to ethical conflict of the ICU nurses studied was moderate, lower than that of nurses in Iran15 and other hospitals in Spain,13 and higher than that of nurses in Portugal.18

In this study, scenario 7 generated the highest level of exposure to ethical conflict, "Realizing that the analgesia and/or sedation being given to the patient is not effective enough and that the patient is suffering", as in the literature reviewed.15,16,18 This is a relatively frequent scenario in these units,16 and seeing the patient suffer may cast doubt on whether everything that can be done is being done, giving rise to conflict.44 However, few studies in nursing ethics and critical care nursing identify this specific scenario, but rather place greater emphasis on dilemmatic scenarios related to treatments considered futile.18 It is interesting to note that scenarios 19 and 17 generated ethical conflict in second and third place: the lack of means (space and time) could prevent good communication which would facilitate dialogue to raise ethical issues in the team and participate in decision-making.16,23

The most frequent moral states in our study are moral outrage and moral distress, as in studies conducted in Spain13 and Portugal18 and in contrast to a study conducted in Iran.15 This may be due to cultural differences. There are studies that show a positive relationship between religiosity and spirituality with the development and maintenance of resilient behaviours,45 the Islamic religion being the most highlighted.15 These resilient behaviours have also been described in the literature in relation to gender, although with contradictory results.46,47

As in the study by Falcó et al.,13 high levels of ethical conflict are associated with moral outrage. This finding is important, because the worse the moral state, the more team participation and decision-making may be compromised.13,17,18,43

A significant relationship was found between professionals who have received training in palliative care and the rate of exposure to ethical conflict, as in the literature reviewed, although with inverse associations.16 It is striking that of the professionals who had received such training, none had a low exposure index and most frequently had a high exposure index. We believe that this may be because this training in end-of-life care and bioethical aspects gives the professional criteria, and limitations in applying these criteria may increase the index of conflict.12

No association was found between burnout, environment, and index of exposure to ethical conflict. This result is striking, given that several studies show that nursing professionals with higher levels of moral distress are more likely to report burnout and a desire to leave the job.14 Alarmingly, the WHO in 2016 already estimated a global shortage of approximately 7.6 million nurses by 2030 for this reason.48 Furthermore, it has been described in the literature that professionals experience less exposure to conflict when they perceive a favourable environment16,23,43 and when they participate in decision-making.16,23 In this sense, the favourable perception of the environment found in this research contrasts with the moderate-high indices of exposure to ethical conflict. With these results, and based on previous research,14 higher burnout scores could also be expected. It should be noted that these concepts had not yet been studied in the selected sample, and therefore there is a lack of previous comparative data.

Personal factors and end-of-life care16 are described in the literature as causes of burnout and moral conflict. Along these lines, Arrogante and Aparicio-Zaldivar7 indicate that interventions focused on helping people to cope with their environment can improve burnout. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, moreover, recognises the inseparable link between the quality of the work environment, excellence of nursing practice, and patient and family care outcomes.49 They propose interventions to address the personal stressors of ICU work, and their official statement proposes interventions focused on the professional, the team, and interventions to mitigate risk factors.49 In addition, they give six standards necessary to establish and maintain a healthy work environment: (1) skilled communication; (2) true collaboration; (3) effective decision making; (4) appropriate staffing; (5) meaningful job recognition; and (6) authentic leadership.49

Based on these recommendations and adjusted to the results of the present study, interventions aimed at encouraging shared decision-making in teams and working on personal factors are proposed, given that self-efficacy and resilience have been shown to be protective factors.50

This study has methodological limitations. The research was conducted in a single centre and the sample was small and convenience. In addition, the characteristics of the population studied do not allow the data to be extrapolated because they do not fit the normal distribution (no nurse in the sample was male and the perception of men and women may be different in some aspects; the nurses have the same initial postgraduate training programme; all participants are western and underwent the same selection process). In relation to the socio-demographic questionnaire, the type of training in palliative care was not investigated and could affect the results. In addition to the limitations inherent to the cross-sectional design, the timing of the study being in the first year of the pandemic, may have influenced the results.

For future research it would be advisable to conduct the study in different centres with different populations to obtain greater diversity and to be able to extend and extrapolate the results.

ConclusionsThe lack of association found in the study between burnout and ethical conflict with the perception of the practice environment suggests that personal factors may influence their development. Therefore, we propose that strategies to reduce the impact of these phenomena should consider individual risk factors and encourage shared decision-making in teams.

FundingThis research received no funding from any entity.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

This study obtained the First Prize for the Best Oral Communication presented at the XLVII National Congress of the SEEIUC.