To identify risk factors present in patients with dysphagia in a population of critically ill patients.

MethodsCase series of a cohort of patients recruited in the intensive care unit (ICU) until hospital discharge. Patients who gave consent and met the inclusion criteria were recruited. The Volume-Viscosity clinical examination method was used for the screening of dysphagia. An uni- and bivariate statistical analysis was performed using odds ratio (OR) to detect risk factors for dysphagia.

Outcomes103 patients were recruited from 401 possible. The mean age was 59,33 ± 13,23, men represented 76,7%. The severity of the sample was: APACHE II (12,74 ± 6,17) and Charlson (2,98 ± 3,31). 45,6% of patients showed dysphagia, obtaining significant OR values (p < 0,050) for the development of dysphagia: older age, neurological antecedents, COVID19, long stay in ICU and hospitalization, and the presence of tracheotomy. COVID19 patients represented 46,6% of the sample, so an analysis of this subgroup was performed, showing similar results, with a Charlson risk (OR:4,65; 95% CI:1,31–16,47; p = 0,014) and a hospital stay (OR: 8,50; 95%CI: 2,20–32,83; p < 0,001) On discharge from the ICU, 37,9% of the population still had dysphagia; 12,6% maintained this problem at hospital discharge.

ConclusionsAlmost half of our patients developed dysphagia. Clinical severity and the presence of tracheotomy were risk factors. We observed in patients with dysphagia a longer stay in both ICU and hospitalization.

Determinar los factores de riesgo presentes en los pacientes con disfagia en relación con una población de pacientes críticos.

MétodoSerie de casos de una cohorte de pacientes reclutados en la unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) hasta el alta hospitalaria. Se reclutaron a aquellos pacientes que dieron su consentimiento y cumplían los criterios de inclusión. El método de exploración clínica Volumen-Viscosidad fue utilizado para la detección de la disfagia. Se realizó un análisis estadístico uni-y bivariante, a través del odds ratio (OR) para detectar los factores de riesgo en la disfagia.

Resultados103 pacientes fueron reclutados de 401 posibles. La media de edad fue de 59,33 ± 13,23; los hombres representaban el 76,7%. La gravedad media fue: APACHE II (12,74 ± 6,17) y Charlson (2,98 ± 3,31). Un 45,6% de los pacientes desarrollaron disfagia, obte-niendo valores significativos de OR (p < 0,050) para el desarrollo de disfagia: la mayor edad, los antecedentes neurológicos, COVID19, la alta estancia en UCI y hospitalización y la presencia de traqueotomía. Los pacientes COVID19 representaban el 46,6%, por lo que se realizó un análisis de este subgrupo observando resultados similares, con un riesgo de Charlson (OR:4,65; IC95%: 1,31–16,47; p = 0,014) y una estancia hospitalaria (OR: 8,50; IC95%: 2,20–32,83; p < 0,001) Al alta de UCI, el 37,9% de la población presentaba todavía disfagia, y mantenía este problema al alta hospitalaria el 12,6%.

ConclusionesCasi la mitad de nuestros pacientes presentaron disfagia. Fueron factores de riesgo la gravedad clínica y la presencia de traqueotomía. Se observó en estos pacientes una mayor estancia tanto en UCI como en hospitalización.

What is known?

Dysphagia is defined as an alteration in the swallowing process. In critically ill patients its presence has been studied as an element which obstructs clinical evolution. Nurses should incorporate its detection into their daily practice.

What it contributes?

This article presents the incidence of dysphagia in an intensive care unit. Its detection was made using a validated test newly used in this unit. We also describe the risk factors related to this clinical problem.

Implications in the study

Nurses in the unit have incorporated dysphagia screening as an element of their daily practice in the care of critically ill patients, thereby raising the awareness of the entire multidisciplinary team in adopting measures to prevent aspiration.

In recent years, an increasing number of publications have highlighted dysphagia as a disorder present in many critically ill patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICU), although there is currently no clear prevalence of this condition.1,2 Some studies have reported the presence of aspiration, a consequence of dysphagia, in up to 40 %–62 % of extubated patients.2,3

Dysphagia is defined as an abnormality of the swallowing process. In the critically ill patient, it can have a multifactorial origin such as direct trauma to the larynx related to the endotracheal tube or tracheotomy, pneumotap volume, weakness of the oral musculature and alteration of the pharyngo-laryngeal afferent or sensory receptors.4–6

Various studies have associated this condition with an increased risk of aspiration, aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, longer hospital stay, poorer health care outcomes and reduced quality of life.1,7–9 These complications in the clinical evolution of patients encourage the development of an interdisciplinary approach to early detection and the adoption of measures to shorten the duration of this problem.3 Detecting dysphagia is essential because, as the study by Schefold et al. found, it is an independent predictor of mortality at 28 and 90 days, with a Hazard ratio at 90 days of 3.74 (95% CI [2.01–6.95]; p < .001) and associated with an excess mortality of 9.2%.10 Awareness of this situation should be developed as a routine for care teams.11 Screening is recommended, as it reduces post-extubation pneumonia and hospital stay, improving oral intake at ICU discharge.12

One of the elements that generates most discussion is the effect that devices provoke in the airway of critically ill patients. Both endotracheal tubes and tracheostomy tubes may have an effect on the development of dysphagia. Although cannulae do not anatomically interfere with swallowing, the pressure exerted for days by the pneumotap on the tracheal wall does. Other factors that according to Medeiros et al. in their literature review influence the biomechanics of swallowing associated with tracheotomy were: reduced laryngeal elevation, insufficient airway closure, stasis in the supraglottic region, reduced cough reflex, reduced airway protection and reduced vocal cord adduction reflex.13

Dysphagia is considered to be a multifactorial process. All factors must be investigated within the context of critically ill patients, as recommended by Skoretz et al. Who were unable to determine the influence of tracheotomy on the development of dysphagia in their systematic review.2 These authors found that pneumotapon values were incorporated as a variable in four of the 10 included studies. 2 Although tracheotomy may induce the presence of dysphagia, other possible coexisting factors are not to be forgotten, such as the presence of facial pain, burns, broncopneumonia, increased secretions, the use of mechanical ventilation for a prolonged period, silent aspiration of saliva, absence of saliva swallowing, altered laryngeal sensation, ineffective cough, need for tracheostomy suctioning, presence of tracheal stenosis and prolonged tracheostomy use.13 The possibility that swallowing is an effective process with adequate secretion control encourages tracheostomy removal, while poor secretion management, as well as the presence of the above factors, delays decannulation.13

There is currently limited evidence in research studies related to interventions by healthcare staff regarding dysphagia in critically ill patients.5 Even so, staff must be trained in the development of clinical practice guidelines and in conducting research to appropriately substantiate clinical decisions.5,14 Avoiding complications and improving oral intake are essential reasons for taking measures that ensure crucially ill patients with dysphagia do not have poorer care outcomes than other patients.15,16

Continuous assessment allows adaptation to the dynamic elements of healthcare, such as the COVID-19 pandemic that has strained healthcare systems in general and critical care units in particular. All this has given rise to consensus documents to continue detecting, assessing and recommend maintaining the detection of dysphagia with personal protective equipment, adapting swallowing procedures to the stages of COVID-19 disease and continuously implementing laryngeal and tracheostomy care throughout admission, without forgetting the rehabilitation of those patients who require it through interprofessional judgement.

The effects of implementing action strategies determine that further work needs to be done in caring for swallowing problems and this is why we must continue improving awareness of the reality of our patients. As a result, the purpose of this research was to determine the risk factors in patients with dysphagia in a critically ill patient population.

Material and methodA case series study of a cohort of critically ill patients admitted to the adult intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital until discharge.

Patients consecutively admitted to the unit and who agreed to participate in the study were recruited. Inclusion criteria were informed consent, being over 18 years of age and with an admission period of more than 48 h, in patients who had required intubation and/or tracheotomy.

Exclusion criteria were: not having required invasive mechanical ventilation, admission with tracheotomy, not having an adequate level of consciousness or contraindication to oral intake or having received it before the test, and having been previously diagnosed with dysphagia.

The recruitment period fell between 1st July 2020 and 31st May 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic was ongoing during the data collection phase and this had an impact on healthcare, and consequently on this study.

Acceptance of study participation was developed with patient follow-up of those recruited until their hospital discharge.

Unit characteristicsThe study was conducted in an adult ICU in a 32-bed tertiary level multipurpose hospital with 1,200 admissions per year (2020 data), with two physiotherapists, but no speech therapist. When a dysphagia problem is detected, consultation with the speech therapist takes place. The unit has a protocol for deflation of the tracheotomy pneumotap and the use of the phonatory valve, which is applied before dysphagia screening tests are carried out.

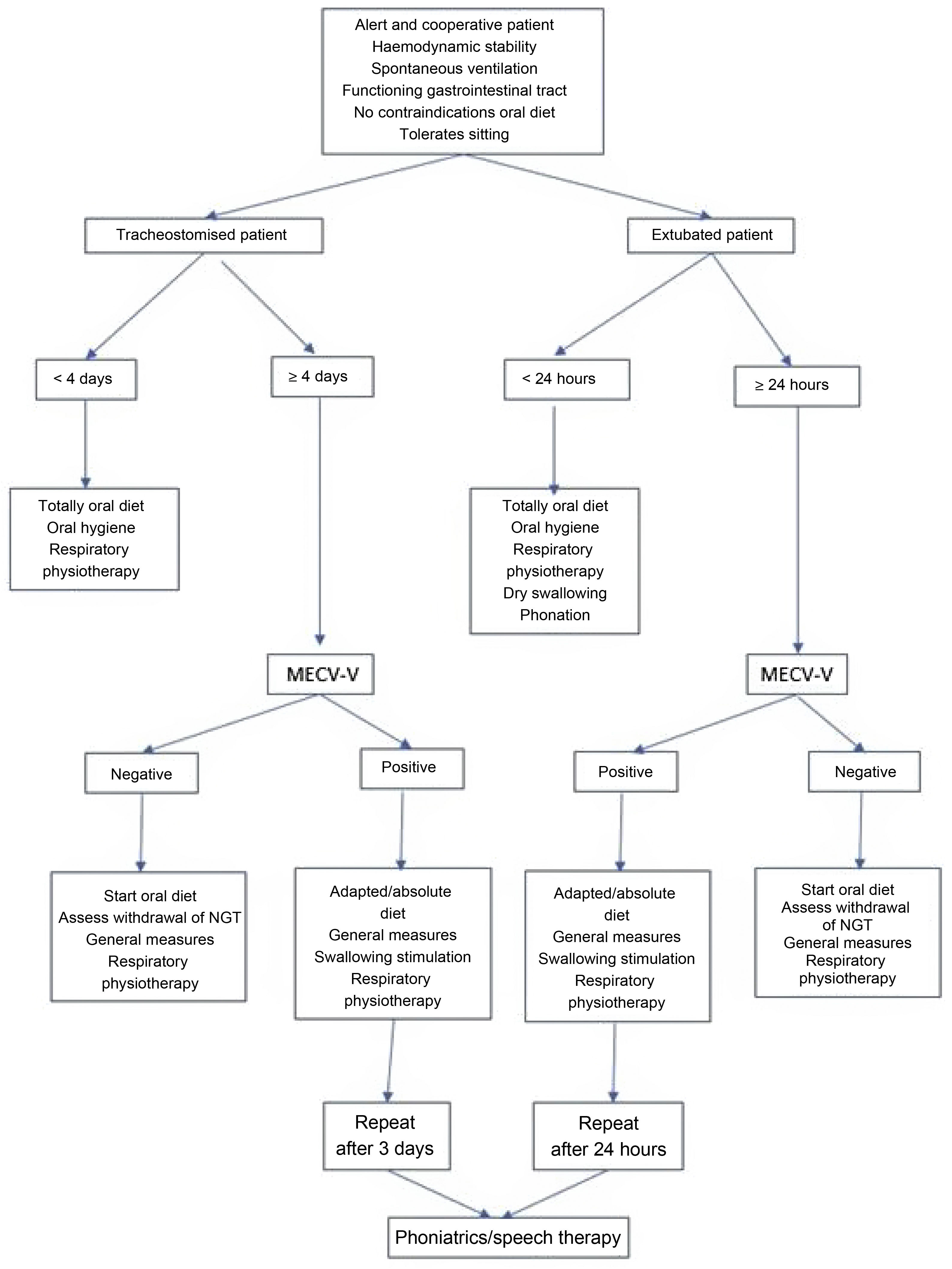

Dysphagia detection procedureThis is performed using the MECV-V test (Volume-Viscosity clinical examination method) on any patient extubated (>24 h), tracheostomised (>4 days) or on high-flow oxygen therapy, who is able to tolerate spontaneous ventilation, but does not show symptoms of dysphagia (Fig. 1).

During the procedure, the patient is kept seated in bed or in an armchair and monitored at all times. In patients with a tracheostomy, the test is performed with the pneumotap deflated and, in those who can tolerate it, with a speaking valve. The MECV-V method was developed and validated by Clavé et al.18 The application of MECV-V is carried out using progressively low (5 mL), medium (10 mL) and high (20 mL) volume boluses of nectar (IDDSI 2), liquid (IDDSI 0) and pudding (IDDSI 4) viscosity. Water and commercial thickener (either starch-based or xanthan-based), peach juice or liquid yoghurt for nectar, gelled water or yoghurt for pudding can be used. The use of food dye allows better observation of food debris, as well as its presence in the oral cavity or lower airway or its exit through the tracheostoma. In this study, blue dye was used for water, red dye for nectar and yellow dye for pudding. The order used to develop the test was: nectar, liquid and pudding.

The clinical symptoms detected by this method of evaluation are:

- •

- ○

Signs of alteration to safety:

Cough

- -

Change in voice

- -

Oxygen desaturation (3% drop in oxygen saturation)

- ○

Signs of impaired efficacy:

- -

Lack of lip seal

- -

Oral residue

- -

Fractionated swallowing

- -

Laryngeal residue

- -

- ○

- ○

The test is considered negative if none of the signs described above are present. The test is considered to be positive (efficacy/safety) when it shows any of the signs described above. Positive signs of impaired safety and efficacy are relevant for rehabilitation treatment and compensatory approaches that may be carried out.

In cases where a positive result is detected for the MECV-V test, the measures shown in Fig. 1 are used and, after the speech therapist's assessment, the nurses are trained by the speech therapist to perform the swallowing exercises adapted to each case.

The test was also performed on discharge from the ICU, during hospital admission and on hospital discharge to control the evolution of recruited patients, in accordance with the speech therapist’s indications.

Data collectionThe following demographic data were collected in the study: age, sex, weight and height, personal history of neurological, respiratory and digestive pathology, as well as home treatment with neuroleptics/sedatives and proton pump inhibitors as dichotomous variables (Yes/No). Other data were: indicators of critical patient severity such as APACHE II and Charlson on admission; days of admission prior to ICU and days of admission to ICU; number of days intubated, or the need for tracheostomy with type of approach; days from admission to first dysphagia test; presence of mixed dysphagia; liquids, nectar and pudding; safety and efficacy; dysphagia at ICU discharge; type of diet at ICU discharge and hospital discharge; Diagnosis of COVID-19, and number of days of hospitalisation.

Statistical analysisData were analysed with the SPSS 25.0 statistical package. Quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). Qualitative data were described as frequency and percentage. The 95% CI was incorporated into the data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normality distribution. Bivariate analysis was performed using Student's t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for qualitative variables. The Odds Ratio was used to detect risk variables. Values of p < .050 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee under reference CEI/CEIm Las Palmas Code: 2019−510-1 and participation was voluntary. The Helsinki declaration on biomedical research was followed at all times. The data were anonymised for statistical processing.

ResultsDemographic dataDuring the study period, 1,074 patients were admitted, of whom 499 required intubation and/or tracheostomy. A total of 103 patients were recruited, 76.7% of the sample were male (n = 79), with a mean age of 59.33 (SD:13.23). The majority were admitted for medical causes, representing 85.4% (n = 88); patients with cardiac and trauma pathology represented 8.7% (n = 9) and 5.8% (n = 6) respectively.

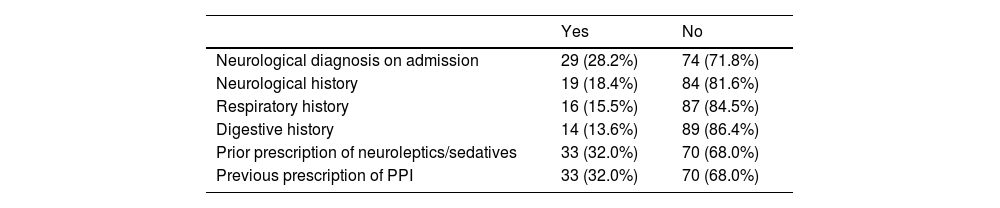

It should be noted that 33% (n = 34) had body mass index (BMI) values classified as obese, 43.7% were overweight (n = 45), and the rest had normal BMI values. The personal history of the patients is shown in Table 1.

Personal history of the sample.

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Neurological diagnosis on admission | 29 (28.2%) | 74 (71.8%) |

| Neurological history | 19 (18.4%) | 84 (81.6%) |

| Respiratory history | 16 (15.5%) | 87 (84.5%) |

| Digestive history | 14 (13.6%) | 89 (86.4%) |

| Prior prescription of neuroleptics/sedatives | 33 (32.0%) | 70 (68.0%) |

| Previous prescription of PPI | 33 (32.0%) | 70 (68.0%) |

PPI, proton pump inhibitors.

Note: Results expressed in frequency and percentage.

Patients had a mean APACHE II on admission of 12.74 (SD: 6.17) and a Charlson comorbidity index of 2.98 (SD: 3.31). Due to the incidence of the pandemic during data collection, we must state that 46.6% (n = 48) of those included in the study were admitted for complications arising from COVID-19, centred on acute respiratory failure requiring invasive ventilatory support.

All patients in the sample required orotracheal intubation. The mean number of days intubated was 10.57 (SD: 6.16). Of these patients, 50.5% (n = 52) required tracheotomy, which was performed with percutaneous technique (n = 39) and with surgical technique (n = 13). Mean ICU stay was 22.24 (SD: 16.90). At discharge from ICU (n = 102), patients were prescribed oral diet (n = 43; 42.3%), modified oral diet (n = 36; 35.3%) and enteral nutrition (n = 23; 22.5%).

Dysphagia evaluation procedureAll patients included in the study were assessed by swallowing tests. The mean time to the first dysphagia test was 17.82 days (SD: 11.98). Of the 103 patients included in the study, 45.6% (n = 47) had dysphagia. Dysphagia to liquids (n = 45), dysphagia to nectar (n = 24) and dysphagia to pudding (n = 16) were detected. The most common alteration was dysphagia to liquids only (n = 20), followed by mixed dysphagia to all three elements (n = 13) and mixed dysphagia to liquids and nectar (n = 9).

On ICU discharge (n = 102), 39 patients still had dysphagia and were unable to achieve calorie targets with oral and /or modified oral feeding.

The mean length of hospitalisation of the total sample was 43.05 (SD: 31.73) days. At hospital discharge (n = 100), the group was fed by oral diet (86%), modified oral (11%) and enteral nutrition (3%). During follow-up, three patients died, one in ICU and two during hospitalisation.

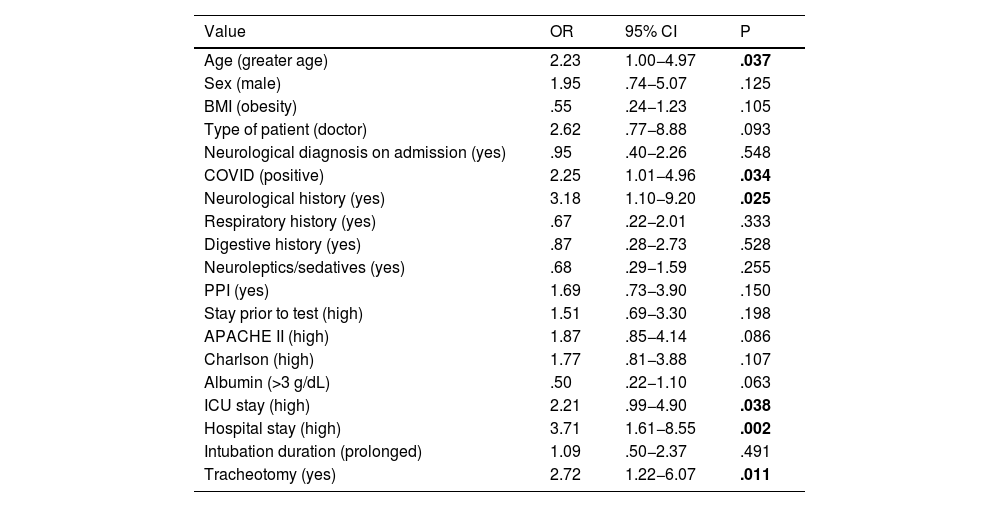

Risk factors related to the development of dysphagiaAmong the risk factors we found that older age, neurological history, a long stay in the ICU and the presence of tracheostomy were statistically significant factors, as shown in Table 2. Patients with dysphagia also spent up to three times longer in hospital than those without dysphagia. Patients affected by COVID-19 pathology developed dysphagia twice as often as non-COVID-19 patients.

Variables associated with dysphagia in critically ill patients.

| Value | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (greater age) | 2.23 | 1.00−4.97 | .037 |

| Sex (male) | 1.95 | .74−5.07 | .125 |

| BMI (obesity) | .55 | .24−1.23 | .105 |

| Type of patient (doctor) | 2.62 | .77−8.88 | .093 |

| Neurological diagnosis on admission (yes) | .95 | .40−2.26 | .548 |

| COVID (positive) | 2.25 | 1.01−4.96 | .034 |

| Neurological history (yes) | 3.18 | 1.10−9.20 | .025 |

| Respiratory history (yes) | .67 | .22−2.01 | .333 |

| Digestive history (yes) | .87 | .28−2.73 | .528 |

| Neuroleptics/sedatives (yes) | .68 | .29−1.59 | .255 |

| PPI (yes) | 1.69 | .73−3.90 | .150 |

| Stay prior to test (high) | 1.51 | .69−3.30 | .198 |

| APACHE II (high) | 1.87 | .85−4.14 | .086 |

| Charlson (high) | 1.77 | .81−3.88 | .107 |

| Albumin (>3 g/dL) | .50 | .22−1.10 | .063 |

| ICU stay (high) | 2.21 | .99−4.90 | .038 |

| Hospital stay (high) | 3.71 | 1.61−8.55 | .002 |

| Intubation duration (prolonged) | 1.09 | .50−2.37 | .491 |

| Tracheotomy (yes) | 2.72 | 1.22−6.07 | .011 |

APACHE II, Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Evaluation; BMI, Body Mass Index; CI, Confidence Interval; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; OR, Odds Ratio; PPI, Proton pump inhibitors.

Note: statistically significant values of p < .050 in bold.

Dysphagia developed in 57.7% (n = 30) of the patients who required tracheostomy, however, patients who did not have tracheostomy developed dysphagia in 33.3% (n = 17) of the cases; this implies an odds ratio of 2.72 between these populations.

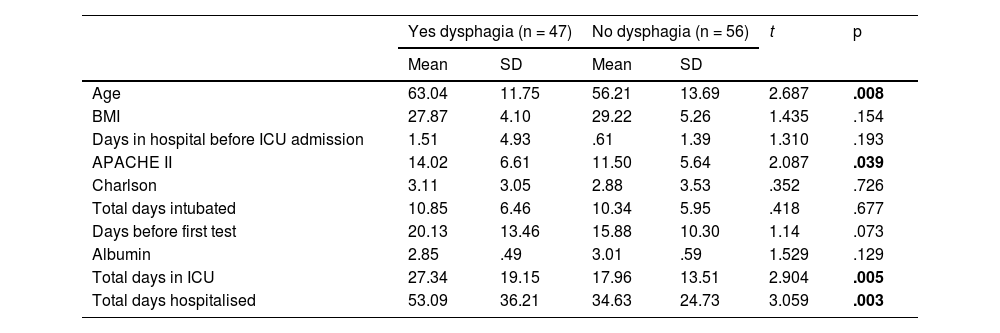

The continuous variables analysed, using Student's t-test, showed that the group of patients who developed dysphagia were older, with a higher APACHE II score, a longer ICU stay and longer hospitalisation (Table 3).

Bivariate analysis of continuous variables between positive and negative dysphagia groups.

| Yes dysphagia (n = 47) | No dysphagia (n = 56) | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age | 63.04 | 11.75 | 56.21 | 13.69 | 2.687 | .008 |

| BMI | 27.87 | 4.10 | 29.22 | 5.26 | 1.435 | .154 |

| Days in hospital before ICU admission | 1.51 | 4.93 | .61 | 1.39 | 1.310 | .193 |

| APACHE II | 14.02 | 6.61 | 11.50 | 5.64 | 2.087 | .039 |

| Charlson | 3.11 | 3.05 | 2.88 | 3.53 | .352 | .726 |

| Total days intubated | 10.85 | 6.46 | 10.34 | 5.95 | .418 | .677 |

| Days before first test | 20.13 | 13.46 | 15.88 | 10.30 | 1.14 | .073 |

| Albumin | 2.85 | .49 | 3.01 | .59 | 1.529 | .129 |

| Total days in ICU | 27.34 | 19.15 | 17.96 | 13.51 | 2.904 | .005 |

| Total days hospitalised | 53.09 | 36.21 | 34.63 | 24.73 | 3.059 | .003 |

APACHE II, Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Evaluation; BMI, Body Mass Index; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; Student’s t-test; SD, Standard Deviation.

Note: statistically significant values of p < .050in bold.

Due to the statistical weight of COVID-19 patients representing 46.6%, a specific analysis was performed for this population. Consisting of 48 patients, in order to assess whether these patients' risk factors for developing dysphagia were symmetrical. No significant differences in composition were found between the non-COVID and COVID-19 populations, in terms of the age variable. However, there were differences between these populations in BMI, as the COVID-19 had a higher BMI value, with a statistical significance of p = .004. When evaluating these groups, with the sex variable, we found an X2 value of 3.823 and p = .041, so that in this sample there is an association between having COVID-19 and being male. The presence of dysphagia in this group was 56.3%, higher than in the whole sample.

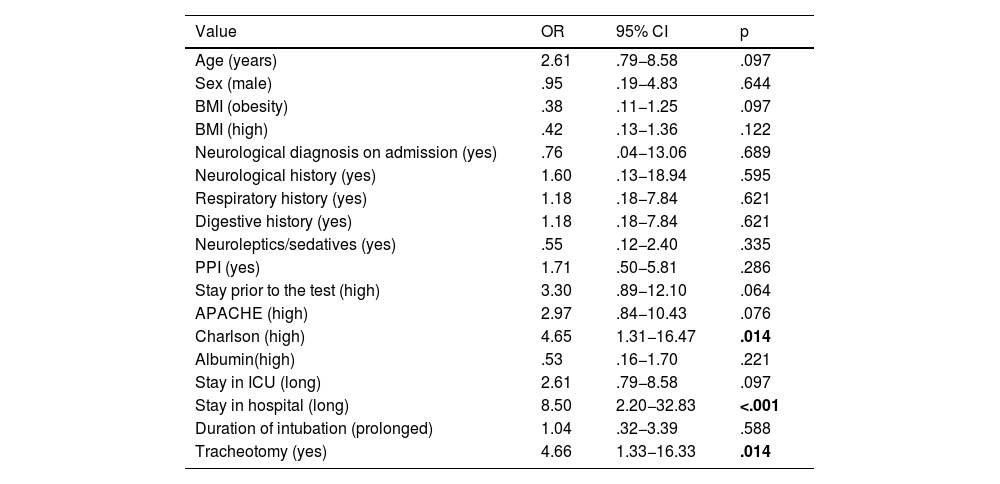

In this COVID-19 population, there is a significant risk, up to four times higher, of developing dysphagia in the presence of a high Charlson score (higher than the mean value of 2.53) and in the presence of tracheostomy. In addition, patients who developed dysphagia spent up to 8.5 times more days in hospital than patients without this nosological entity (Table 4).

Risk variables in the COVID-19 population.

| Value | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 2.61 | .79−8.58 | .097 |

| Sex (male) | .95 | .19−4.83 | .644 |

| BMI (obesity) | .38 | .11−1.25 | .097 |

| BMI (high) | .42 | .13−1.36 | .122 |

| Neurological diagnosis on admission (yes) | .76 | .04−13.06 | .689 |

| Neurological history (yes) | 1.60 | .13−18.94 | .595 |

| Respiratory history (yes) | 1.18 | .18−7.84 | .621 |

| Digestive history (yes) | 1.18 | .18−7.84 | .621 |

| Neuroleptics/sedatives (yes) | .55 | .12−2.40 | .335 |

| PPI (yes) | 1.71 | .50−5.81 | .286 |

| Stay prior to the test (high) | 3.30 | .89−12.10 | .064 |

| APACHE (high) | 2.97 | .84−10.43 | .076 |

| Charlson (high) | 4.65 | 1.31−16.47 | .014 |

| Albumin(high) | .53 | .16−1.70 | .221 |

| Stay in ICU (long) | 2.61 | .79−8.58 | .097 |

| Stay in hospital (long) | 8.50 | 2.20−32.83 | <.001 |

| Duration of intubation (prolonged) | 1.04 | .32−3.39 | .588 |

| Tracheotomy (yes) | 4.66 | 1.33−16.33 | .014 |

APACHE II, Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Evaluation; BMI, Body Mass Index; CI, Confidence Interval; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; PPI, Proton pump inhibitors; SD, Standard Deviation.

Note: statistically significant values of p < .050 in bold.

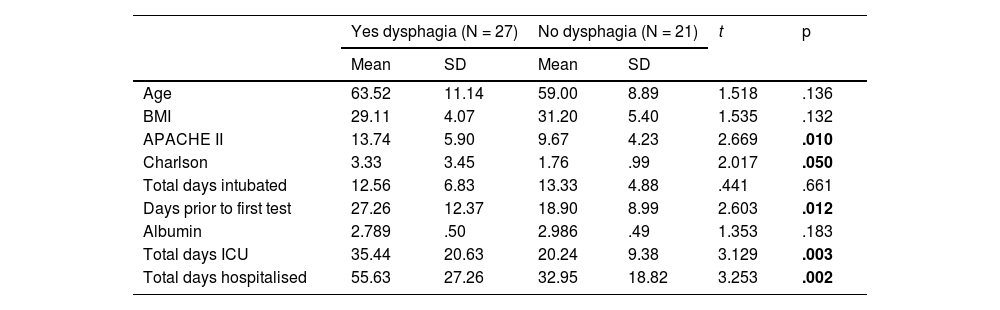

In the analysis of the continuous variables, we found values that follow the trend of the general population in patients admitted for COVID-19. In this population, those who developed dysphagia were older, had higher APACHE II and Charlson scores on admission. The delay in performing the diagnostic test was also a significant value, so that, in addition, people with dysphagia spent more days in the ICU and in hospital (Table 5).

Bivariate analysis of the COVID-19 population and the development of dysphagia.

| Yes dysphagia (N = 27) | No dysphagia (N = 21) | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age | 63.52 | 11.14 | 59.00 | 8.89 | 1.518 | .136 |

| BMI | 29.11 | 4.07 | 31.20 | 5.40 | 1.535 | .132 |

| APACHE II | 13.74 | 5.90 | 9.67 | 4.23 | 2.669 | .010 |

| Charlson | 3.33 | 3.45 | 1.76 | .99 | 2.017 | .050 |

| Total days intubated | 12.56 | 6.83 | 13.33 | 4.88 | .441 | .661 |

| Days prior to first test | 27.26 | 12.37 | 18.90 | 8.99 | 2.603 | .012 |

| Albumin | 2.789 | .50 | 2.986 | .49 | 1.353 | .183 |

| Total days ICU | 35.44 | 20.63 | 20.24 | 9.38 | 3.129 | .003 |

| Total days hospitalised | 55.63 | 27.26 | 32.95 | 18.82 | 3.253 | .002 |

APACHE II, Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Evaluation; BMI, Body Mass Index; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; Student’s t-test; SD, Standard Deviation.

Note: statistically significant values of p < 050 in bold.

At discharge from ICU of the total population, 39 (37.9%) patients still had an active dysphagia process. Notably, 13 patients (12.6%) were discharged from hospital with dysphagia still active.

DiscussionIn our study, dsyphagia accounted for 45.6% of the patients included, similar to other studies.2,8,19 However, authors such as Bordejé et al., obtained much lower values, 11.6% in their general population and 22.7% in their intubated population, using a different test to us, including the modified swallowing volume viscosity test (mV-VST).20 In a population of intubated patients our data collected an incidence of dysphagia that is close to the 41% reported in the systematic review by McIntyre et al.21

Dysphagia in critically ill patients has a multicausal aetiology, with severity expressed by the APACHE II index and comorbidity (Charlson), which both in the general population and only in COVID-19, have shown significant differences. This fact was already mentioned by previous studies.10,19,22 Zuercher et al. determined by logistic regression that the independent risk factors for developing dysphagia were: history of neurological disease, emergency admission, days on mechanical ventilation, APACHE II and the number of days on extracorporeal clearance therapy.22

Of the risk factors presented by our population, a history of neurological disease played an essential role, with these events also being reported by other studies.22,23

Among the mechanical ventilation devices that influence the occurrence of this problem, tracheotomy was found to be a risk factor, in line with previous studies.2,24–26 This is explained by the fact that tracheotomy has to be performed in cases of prolonged intubation in order to progress in the withdrawal of mechanical ventilation and, therefore, a device whose factors such as volume, size of the cannula and pressure, as advocated by other authors as a risk factor mechanism, is maintained.2 Although the presence of tracheotomy can be considered a triggering factor for dysphagia, the incidence of other possible concurrent factors that may cause its appearance should also be assessed, such as: the presence of facial trauma, burns, bronchopneumonia, increased secretions, prolonged use of mechanical ventilation, silent aspiration of saliva, absence of saliva swallowing, altered laryngeal sensitivity, ineffective cough, need for tracheostomy suctioning, presence of tracheal stenosis and prolonged tracheostomy use.13 The likelihood of effective swallowing coupled with adequate secretion control encourages tracheostomy removal, while decreased or absent spontaneous swallowing, poor secretion management and the presence of the factors listed above delay decannulation of patients.13 The patient's condition and the possibility of advancing device removal, deflation of the tracheotomy balloon and the use of phonatory cannulae may decrease the duration of dysphagia.27 However, in the literature review of 29 studies carried out by Cabezas et al. only four found a direct relationship between tracheotomy and dysphagia, while 11 rejected it and 15 assumed it as a possibility in the conclusions.28 Another aspect to highlight is that muscle weakness should be related as a factor associated with tracheotomy patients who develop dysphagia.1,9,28

One point highlighted in the literature is the need for bedside assessment of dysphagia, using tests validated by critical care professionals.3,22,29–31 Training healthcare staff in these tests can help to implement corrective activities to prevent aspiration episodes.9,12,32 Specific training of professionals in dysphagia helps to introduce oral intake earlier and improves patient survival.32 However, although professionals consider dysphagia to be an important problem, 55.3% (n = 21) of the units in Spain still do not have an established screening protocol, and only 7.9% (n = 3) apply it systematically to all patients.11

Our data show an increase of ICU and hospital stay in patients with dysphagia, as do other previous studies,1,20 and therefore the complications derived from feeding management could be related factors.15,32

An important fact to bear in mind is the statistical weight that COVID-19 patients have had when it comes to developing dysphagia, and the fact that they have been treated in the first waves, according to the recommendations, with early intubation to treat acute respiratory distress syndrome, undoubtedly led to an increase in cases of dysphagia.26,33 The need to test all patients equally has been the subject of consensus documents and research.16,17,34 In our study, we observed in the COVID-19 population a relationship between a significant delay in carrying out the first test and the presence of dysphagia, which was not significant in the general population. This fact may be related to the greater severity of these patients, who underwent more days of mechanical ventilation than non-COVID-19 patients, which delays the time at which the swallowing test can be performed. Therefore, as mentioned by Fritz et al. a long-term strategy should be implemented to accommodate the needs of these patients.35

Finally, it should be emphasised that proper management of a problem such as dysphagia requires a multidisciplinary approach by all critical care healthcare professionals, both doctors and nurses and other related fields, such as speech therapists, speech therapists and otorhinolaryngologists.3,17 Healthcare professionals must continue to research in this field, as there are currently no evidence-based international clinical guidelines that support the guidelines to be followed in the detection, prevention and management of post-extubation dysphagia.36

Study limitationsThe main limitation of this study is that, being a series of cases, we do not know exactly what the magnitude of the problem is in relation to the total admitted population, but it may be the first step for future research with the appropriate methodology. Furthermore, it has allowed us to detect the reality of a problem that needs to be addressed, as the incidence affects a significant number of critically ill patients. It should also be noted that our work was carried out during the pandemic, which increased the pressure of care, an element that could not be controlled by the authors, so we were not in the usual conditions of a tertiary hospital. Furthermore, our data indicate that COVID-19 patients required more time on mechanical ventilation, which may be a factor to be explored, although our data on days intubated did not determine this. In the future, it will be necessary to investigate all aspects of tracheotomy involved (volume, pressure and cannula size) in order to properly assess the importance of each element within the overall technique.

ConclusionDysphagia was a symptom present in almost half of the sample studied, being higher among patients admitted for COVID-19. We detected severity (APACHE II) and comorbidity (Charlson) as risk factors for developing dysphagia, as well as the presence of tracheostomy. Patients with dysphagia also had a longer ICU and hospital stay, which is very important in view of the risks that can result from prolonged institutionalisation.

Finally, this study determines that dysphagia is an important alteration in the population of critical patients who require orotracheal intubation and where the severity of the disease and the presence of infraglottic devices influence its development. This is why, as healthcare professionals, we must test and treat these patients in a multidisciplinary manner in order to avoid this complication.

FundingThe study was funded by the authors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.