To identify studies that assess the quality of life of people with a peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC), a midline catheter (MC) and a peripheral insertion central catheter (PICC).

MethodUsing a scoping review design we included studies that reported the quality of life of adult patients with the aforementioned vascular access devices. With a specific keyword search strategy performed in December 2023 we searched, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane, Scopus and ProQuest databases. There were no restrictions on the date of publication and studies in English, Spanish or Portuguese were included. Following our inclusion an exclusion criteria, extracted findings reported with the patterns, advances, gaps, evidence for practice and research framework.

ResultsOf 6317 sources we included 151 papers for full text screening and included 21 studies for data extraction and interpretation. PICCs were the primary catheter reported in seven studies. All remaining studies included more than one device. The most frequently used questionnaire was European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (eight studies) followed by the Short Form Health Survey, the Karnofsky scale, Functional Living Index-Cancer questionnaire, Palliative Care Outcome Scale FACT-B questionnaire. In eight studies a researcher developed without validated questions were used alone or combined with other validated instruments.

ConclusionThere are no validated questionnaires measuring patient quality of life with specifically for three of the most commonly inserted vascular access devices used in healthcare to date. Opportunities exist to develop and validate a patient related and catheter device specific quality of life instrument.

Identificar estudios que evalúen la calidad de vida de personas con un catéter intravenoso periférico (CIVP), una línea media (LM) y un catéter central de inserción periférica (PICC).

MétodoSe utilizó un diseño de revisión de alcance en el que se incluyeron estudios que midieran la calidad de vida de pacientes adultos que portaran los dispositivos de acceso vascular mencionados. Con una estrategia de búsqueda por palabras clave específica realizada en diciembre de 2023 se realizaron búsquedas en las bases de datos CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane, Scopus y ProQuest. No hubo restricciones en cuanto a la fecha de publicación y se incluyeron estudios en inglés, español o portugués. Siguiendo nuestros criterios de inclusión y exclusión, los hallazgos se describieron siguiendo la estructura “patrones, avances, lagunas, evidencia para la práctica y contexto de investigación”.

ResultadosDe 6.317 registros se incluyeron 151 registros para el cribado de texto completo y finalmente se incluyeron 21 estudios para la extracción e interpretación de datos. El PICC fue el dispositivo más estudiado, n = 7 estudios. Todos los estudios restantes incluyeron más de un dispositivo. El instrumento utilizado con más frecuencia fue el European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (n = 8 estudios), seguido de la Short Form Health Survey, la escala de Karnofsky, el instrumento Functional Living Index-Cancer y el cuestionario Palliative Care Outcome Scale FACT-B. En n = 8 estudios se utilizó un instrumento desarrollado por el investigador no validado, solo o en combinación con otros instrumentos validados.

ConclusiónNo existen hasta la fecha cuestionarios validados que midan específicamente la calidad de vida de los pacientes con tres de los dispositivos de acceso vascular de mayor uso en la asistencia sanitaria. Los resultados de esta revisión muestran la oportunidad de desarrollar y validar un instrumento de calidad de vida específico para el paciente portador de dispositivos de acceso vascular.

The use of vascular access devices is increasing, especially those long-term devices that patients wear for extended periods for the treatment of diseases such as cancer. These devices could have an impact on the quality of life of these patients.

What it contributesDespite the fact that understanding the impact of these devices on patients' quality of life could assist both in device selection and management strategies, in this scoping review, we have observed that there are no validated instruments to measure this impact.

A vascular access device (VAD) represents a variety of invasive catheters inserted into human anatomy usually for the infusion of intravenous drugs, blood products, fluids and nutrition into the venous system.1 Historically, the term vascular access was associated with dialysis but in recent years it has become accepted terminology to represent the variety of invasive venous and arterial access devices inserted into veins and arteries. The most common VAD is the peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC), and global estimates suggest that 60% of hospitalised patients receive this device.2,3 Other VADs include midline catheters (MC), peripherally inserted catheters (PICC) and then centrally inserted central catheters. Device selection is often influenced by the characteristics of the planned infusion or medication type, the estimated duration of treatment, the patient’s healthcare condition, and the patient’s venous assessment.4 Numerous clinical policies and standard operating procedures for VADs exist as they require specific care given, they are associated with a variety of complications.5,6 In general, these complications originate in the vein and have a physiological mechanism influenced by the VAD size and infusates used contributing to thrombosis and infection and ultimately catheter failure. Others negative outcomes are attributed to poor management of the device leading skin damage and to infectious complications.7,8 Specifically, catheter-related bacteraemia contribute to increased morbidity, often increased length of hospital stay, prolonged treatment,9 all of which can compromise quality of life (QoL).

Given the extensive use of intravenous therapy in hospitalised patients, the use of VADs will continue as a standard of care. Additionally, given healthcare is shifting to community models of care, ambulant, outpatient and home care settings. Globally, evidence suggests an increase in home hospitalisation services and outpatient treatment delivery.10 In both healthcare delivery approaches, the patient goes about their daily life with the VAD inserted.11 Therefore, it would be timely and important to identify if VADs impact on QoL.

The WHO defined quality of life in 1995 as “individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns”.12 Since then, definitions have evolved often with health related QoL and QoL being used interchangeably.13 For the purpose of this review, we use QoL to represent health status associated with 3 specific VAD types: PIVC, MC and PICC. We suggest that the use of VADs might affect different dimensions of patient activity and healthcare professionals should be cognisant of this phenomenon when assessing QoL. For example, it is important to acknowledge that the person who receives the VAD will have to continue to function with it. Patient or provider reported QoL events could influence perceptions of body image, patient acceptance of the device and this may have an emotional and psychological impact on patients.

It is over 100 years since the first intravenous devices were inserted into human anatomy. Therefore, one could assume that a robust understanding of how they impact patient functionality and QoL is known. Furthermore, given the widespread innovation related to VADs we suggest acceptance of these devices is evolving and wonder if QoL aspects are evident in the literature. Patients who require specific care could wear the device 24 h a day and this could have an impact on the daily routine and therefore quality of life of patients. Qualitative studies show that VADs has an impact on the oncology patient’s experience during treatment in aspects such as pain, the performance of activities of daily living, and the need for education for device maintenance, among others.11,14,15 Additionally, there are well-established implemented QoL instruments for specific VAD type,16,17 specifically, one for use in dialysis is the haemodialysis access-related quality of life instrument.18,19 Consequently, it is important to better understand if QoL instruments exist specifically, PIVC, MC and PICC and therefore, a synthesis of evidence on this topic is warranted.

The aim of this scoping review is to reveal studies that assess the QoL of people with PIVC, MC and PICC to identify and describe the instruments developed or validated use for the assessment of QoL. The intention of this study is to provide an overview of the evidence available regarding QoL of patients with these specific devices and identify any knowledge gaps on the topic.

MethodDesignA scoping review has been done. The JBI scoping review methodological approach was used in the execution of this scoping review.20 The academic literature recognizes the JBI scoping review guideline for its rigor, transparency, and reliability.21 A protocol was established by the review team to clarify the review question, goals and eligibility requirements.

Review questionThe primary review question for this study is: What quality of life assessment instruments are used in relation to patients who have a PIVC, MC and PICC vascular access devices? The PCC framework20 (P = population, C = concept and C = context) was used to carry out this review.

Inclusion criteriaPopulationThis review included studies with adult patients with a PIVC, MC and PICC. Paediatric patients (under 18 years of age) were excluded.

ConceptThe review included studies that evaluated the patient’s QoL in relation to their vascular access devices. More specifically, studies which measure the quality of life of a patient, by using questionnaires, scales, tools or instruments. Studies which focus on patients experience or satisfaction were not included if they did not refer to the evaluation of patients ‘quality of life’. The primary focus in relation to venous vascular access devices included, PIVC, MC, and PICC devices, however if these were in combination with other devices e.g. Implanted Venous Access Devices (PORT) or Central Venous Catheters (CVC) we included these papers. Studies which focused solely on PORT and CVC were not included. Studies referring to haemodialysis were excluded.

ContextThis review took a broad approach and included both inpatient and outpatient clinical settings.

Types of sourcesThis review considered quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies, there was no limitations on study design such as experimental and non-experimental studies. Grey literature was included in the form of theses or dissertations. However, full texts of eligible papers were required for potential inclusion and data extraction. Protocols or conference abstracts of studies were excluded. Studies were limited to English, Spanish and Portuguese.

Search strategyThe search strategy was designed to identify both published and unpublished studies. An initial search was conducted to identify relevant articles, which assisted identifying the keywords used within the search strategy alongside the content knowledge of the review team. The databases searched included CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane, Scopus and the ProQuest database was searched for theses and dissertations. The search strategy developed, using free-text keywords and index terms, was adapted for each database. The search strategies used are described in Appendix I. Each search was conducted in December 2023.

Study selectionOnce the search was completed in each database all identified sources were collated into EndNote® reference manager22 and the duplicates were removed. The remaining sources were then exported from Endnote into Rayyan cloud-based software application tailored for researchers conducting systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses for screening.23 The screening process was carried out in two stages. For the first stage of the process, the review team (OH, CD, VA, SL, PC, SU) independently screened the title and abstract of each source for inclusion into the review. We screened the full text of the remaining sources for eligibility. The study selection process alongside rationales for sources excluded at the full text screening stage are presented in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.24 Any disagreements between reviewers in the screening stage was resolved via discussion or by other reviewers.

Data extractionData from the included studies was extracted by four independent reviewers. A data extraction developed by the reviewers was used. The tool was piloted by four reviewers (OH, CD, VA, SL) initially on one study each to ensure consistency with the extraction. Any disagreements between reviewers in the screening stage were resolved via discussion or by other reviewers (PC, SU). Data extraction was an iterative process, and as the writers gained greater familiarity with the sources and underlying relational principles, they made modifications to the data-extraction form. Extracted data included geographical location, methodology, type of vascular access device studied, the QoL instrument used, aim and main findings.

Data analysis and presentationQuality appraisal is not expected in Scoping reviews, however, results were analysed and then reported using the PAGER framework principles.25 The JBI rules for reporting scoping reviews are supplemented by the PAGER framework, which contains five domains: Patterns, Advances, Gaps, Evidence for practice, and Research recommendations.

ResultsAfter conducting the search strategy within each of the databases, 9013 records were sourced. Duplicates were removed in Endnote which resulted in 6317 records undergoing title and/or abstract screening. Thereafter, 151 records were considered for full text screening. An initial attempt was made to retrieve all literature, 27 recordswere not retrieved as the full text was not available for these studies, the remaining 124 records underwent further screening, and 21 studies were included in the review. The search process can be noted in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses flow diagram (Fig. 1).24

Table 1 provides a detailed summary of each of the 21 included papers as relevant to our scoping review objective. The included studies were published over a 24-year period ranging from 1999 to 2023. Since the first reported study in 1999, a hiatus was then noted until 2015. 14 studies have been published since 2020. Regarding the country of publication, most studies were published in China (n = 10). The most common methodology of included studies was quantitative (n = 19) with two systematicreviews. Specific study designs that measured QoL were varied; most of them were observational studies (n = 8) or randomised control trials (RCT) (n = 5), two studies did not identify their study design however one of these did refer to randomly dividing participants. The number of participants between all primary studies ranged from 28 participants to 357.

Study characteristics.

| Author (Year), country & design | Participants disease (number of participants, n) | Type of VAD | Quality of life tool/scale/instrument used | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolgeo et al. (2023), Italy31Observational study | Pleural mesothelioma (n = 28). | PICC | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13 (specific for lung cancer) | PICC placement did not appear to adversely affect the quality of life of patients. 96.4% reported no complications during PICC implantation and no complications were reported during the observation period. |

| Chrisanthopoulou et al. (2023), Greece35RCT | Breast, colorectal, lung cancer and other types (n = 120). | PORTPIVC | Self-administered 5-level EQ-5D version (EQ 5D-5L)European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EORTC QLQ-C30 | Whereas the functional and symptom scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (oncology specific) questionnaire were similar in both groups the global health status was significantly improved both at 3 mo and 6 mo follow up. EQ-5D-5L scores improved significantly at 6 mo in PORT patients vs. PIVC. |

| Erişen and Yilmaz (2023), Turkey44Observational study | Metastatic colon cancer (n = 103). | PORTPIVC | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EORTC QLQ-C30 | There was not significant differences in the QoL (except social function) according to the chemotherapy method (PORT vs. PIVC) |

| Huang et al. (2023), China28RCT | Breast cancer (n = 160). | PICC | FACT-B + 4 Questionnaire scale | For patients with PICC lines who have breast cancer, the hospital-community-family tertiary linkage nursing approach can enhance compliance and quality of life. |

| Huang et al. (2022), China49Observational study | Ovarian cancer (n = 66). | PICC | SF-36 scale | The implementation of an online multimodal nursing program has the potential to greatly enhance the psychological fortitude and health-related quality of life of asymptomatic PICC-RT patients. |

| Yeow et al. (2022), Singapore50Systematic review and network meta-analysis of RCTs | Solid and hematologic malignancies | NTCPICCTIVAD | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer EORTC QLQ-C30 Non-validated questionnaireEQ-5D questionnaireDevice-specific questionnaire | QoL was documented in 7 research.When compared to other CVADs, TIVAPs were found to be superior in terms of quality of life Of all the CVADs, TIVAPs were shown to have the best safety profile.The study revealed that TIVAPs outperformed other CVADs in terms of QoL and comorbidities.The safety profile of TIVAPs was shown to be the greatest among all CVADs. |

| Li et al. (2022), China37Not specified (randomly divided) | Lung, liver, gastric, breast and blood cancer (n = 150) | PICCPORT | Karnofsky score | From the perspective of the patients’ quality of life, the fully implantable infusion port catheterisation through the internal jugular vein was noted to be preferable. |

| Burbridge et al. (2021), Canada34Observational study | Breast or colorectal cancer (n = 101). | PICCPORT | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer General Quality of Life assessment (EORTC QLQ-C30)A locally developed quality of life survey (QLAVD) | There was no significant differences between the two groups in relation to the EORTC QOL, but patients in the port group had significantly poorer appetite than those with in the PICC group at three months. In relation to the QLAVD survey the port group's average scores for pain related to device insertion and use were significantly higher than those of the PICC line group at baseline and at three months. |

| McKeown et al. (2021), USA39Observational study | Acute myeloid leukaemia (n = 50). | PICCTCC (Hickman) | Specifically developed questionnaire assessing patient-reported experiences with CVCs, including impact on quality of life and daily activities. | Comparable effects on quality of life were observed with both PICCs and TCCs, with minor variations in specific aspects, such as PICCs causing more interference with lying in bed and dressing, while TCC hindered showering more. Anguish and discomfort showed no significant variations, and most patients experienced activity limitations and pain associated with CVC |

| Song and Ma (2021), China42Retrospective study | Malignancy (lung, gastric, hepatic, breast carcinoma and others) (n = 113). | PICC | Quality of Life Core Scale (QLQ-C30). | Prior to the intervention, the two groups' quality of life did not differ significantly (P > 0.05). Following the intervention, both groups’ quality of life scores were higher than they were prior to it (P < 0.05), and the intervention group’s scores were higher than the control group’s (P < 0.05). |

| Clatot et al. (2020), France33RCT | Breast cancer (n = 256). | PICCPORT | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30Home-made satisfaction questionnaire | PICCs exhibit a higher risk of catheter-related severe adverse events, specifically deep vein thrombosis, and result in more patient discomfort compared to PORTs, despite no discernible difference in overall quality of life. |

| Ding et al. (2020), China36RCT | Malignant tumors (n = 98). | PICC | SF-36 scale | Tai chi improves the quality of life in at-home patients with long-term PICC. |

| Lv et al. (2020), China38Prospective study/Observational study | Malignant tumors (lung, gastric, liver, breast, cervical cancer, others) (n = 148). | PICC | SF-36 scale | Cluster nursing efficiently improves hypercoagulable and hyperviscosity states, reducing venous thrombosis risk, alleviating anxiety, and enhancing overall quality of life, as evidenced by notably higher SF-36 scores in the intervention group. |

| Qi et al. (2020), China29Retrospective study | Thyroid cancer (n = 188). | PICCTIVAD | Self-made questionnaire: QoL totalled to a score of 10 points. It included psychological, physical and social function and self-evaluation. | The PICC group had significantly lower QoL score than the TIVAP group (P < 0.05). |

| Zhang et al. (2020), China43Not specified | Blood tumor (n = 145). | Arm PORTChest PORTPICC | Karnofsky scoring criteria | Arm and chest wall infusion PORTs show higher quality of life scores, lower fatigue levels, and better success rates with fewer complications compared to PICC. |

| Magnani et al. (2019), Italy27Observational study | Palliative care (cancer, non-cancer) (n = 90). | PICCMCShort MC | Palliative care Outcome Scale | The quality of treatment can be positively impacted by medium-term intravenous catheters, and the procedures involved in inserting these vascular access devices are well tolerated. |

| Robinson et al. (2018), Canada41Systematic Review | Breast cancer | One paper in this review considered the eligible devices of this reviewPORTPIVC (52) | Study which compares PORT and PIVC used a custom made questionnaire. | 5 studies with 1584 distinct citations were included. Questionnaires were utilized in 3 studies (n = 706) to evaluate the following QoL.Both central access patients and patients without a central access seemed to have very good catheter-associated quality of life.The systematic review draws attention to the paucity of solid data defining the best kind of venous access for patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Studies' rates of complications (infection, thrombosis and malposition) differed, and the outcomes of quality-of-life evaluations were inconsistent. There were no clear-cut findings that which venous access approach was better than the others. |

| Fang et al. (2017), China30Observational study | Malignant tumours (breast cancer, lung cancer, gastrointestinal malignancy, other cancer cases (including ovarian cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and liver cancer) (n = 145). | PORTPICCNTC | A questionnaire modified by three-round expert inquiry. | Compared to PICCs and NTCs, ports have fewer problems, better patient satisfaction, and a superior quality of life. |

| Kang et al. (2017), China40Pilot exploratory study | Lung cancer, digestive tract cancer, breast cancer, haematologic malignancy and other (n = 357). | PICC | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30)Self-made questionnaire | Different types of PICC-using cancer patients have varying health-related QOL. PICCs may have little impact on the health-related QOL of cancer patients. |

| Bortolussi et al. (2015), Italy32Observational study | Pancreatic, stomach and other miscellaneous cancer and non-neoplastic diseases (n = 48). | PICCMC | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core-15-Palliative (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL) | QoL (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL) significantly improved after 1 week for nausea (among the physical symptoms) and also globally. |

| Bow et al. (1999), Canada26RCT | Solid tissue malignancies (n = 120). | PIVCPORT | FLI-C questionnaire | PORTs were safe and efficient, but despite a decrease in anxiety, anguish, and discomfort associated with access, they had no discernible effect on functional quality of life. |

Abbreviations: CVC: Central Venous Catheter; NTC: Non-tunnelled catheter; PICC: Peripherally inserted central catheters; PIVC: Peripherally inserted venous catheter; PORT: Implanted Venous Access Device; QoL: Quality of Life; RCT: Randomised Controlled Trial; TCC: Tunneled Central Catheter; TIVAD: Totally implantable venous access port; VAD: Vascular access device.

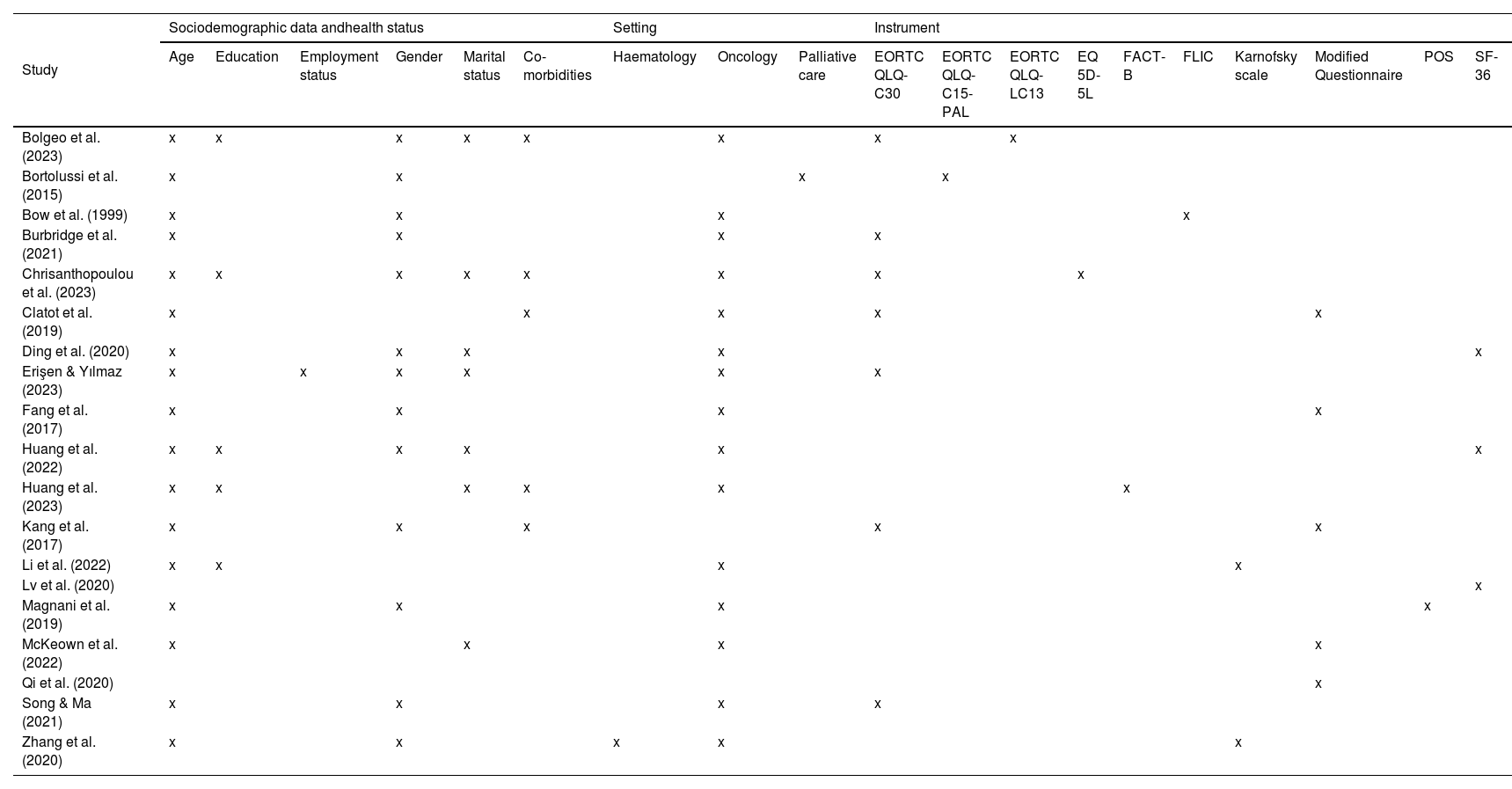

PICCs were the primary focus in seven studies. All remaining studies included more than one device, PIVC and totally implantable venous access device (TIVAD) (n = 3), PICC, TIVAD and non-tunnelled catheter (NTC) (n = 1), PICC and MC (and short midline) (n = 2), PICC and TIVAD (n = 4), PICC and tunnelled central catheter (TCC) (n = 1), TIVAD including arm location and PICC (n = 1). Of the 21 included studies, eight papers used the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30). Three of these eight studies employed an additional, independently developed, device-specific questionnaire. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) was used by three studies led by researcher from China. Two studies used the Karnofsky scale. Other studies used the Functional Living Index-Cancer (FLI-C) questionnaire,26 the Palliative Care Outcome Scale27 and the FACT-B questionnaire,28 specifically designed for breast-cancer patients. Two papers failed to clearly define a specific scale, one retrospective study described a scoring system measuring psychological function, physical function, social function and self-evaluation29 whereas a three-round expert inquiry was used to modify a questionnaire in an observational study by Fang et al.30 The main characteristics of the instruments used in the included studies are shown in Appendix II.

Of the 19 primary papers, specifically focusing on the VADs the use of ultrasound in the insertion of at least some of the devices was noted in seven papers. In relation to device insertion, nine studies did not refer to who inserted the devices of interest. The remaining papers referred to the following professional disciplines as inserters, nurses (n = 5), physicians, (n = 2), interventional radiologist (n = 1), interventional radiologist and nurse (n = 1) and vascular access device team (n = 1).

An inconsistency in the timeline that quality of life was assessed in the 17 studies was found26–28,30–43 while two studies did not mention when data about quality of life was collected.29,44 Baseline data measurement, was performed before catheter insertion in 5 studies.28,32,36,38,42 In two studies this was reported at the time of insertion.31,40 Some studies established this time of QoL measurement occurring at the first chemotherapy cycle.26,33

With regard to post insertion follow up assessment, most of the studies report this occurring after 3 mo of catheter insertion and in 4 cases after 6 mo.31,34,35,38 Longer periods were considered 7, 9 and 12 mo.31,37 In one study shorter periods were considered 3, 7 and 14 days27 while Kang et al. reported a median time of 27 days.40 One study that reported catheter removal was included in a list of QoL measures.30 Numerous factors, including age, gender, co-morbidities, and setting, were gathered in the various studies. These are presented in Table 2 together with the specific QOL evaluation scale used.

Summary of themes assessed in each study and instrument used.

| Study | Sociodemographic data andhealth status | Setting | Instrument | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Education | Employment status | Gender | Marital status | Co-morbidities | Haematology | Oncology | Palliative care | EORTC QLQ- C30 | EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL | EORTC QLQ-LC13 | EQ 5D-5L | FACT-B | FLIC | Karnofsky scale | Modified Questionnaire | POS | SF-36 | |

| Bolgeo et al. (2023) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Bortolussi et al. (2015) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Bow et al. (1999) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Burbridge et al. (2021) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Chrisanthopoulou et al. (2023) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Clatot et al. (2019) | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Ding et al. (2020) | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Erişen & Yılmaz (2023) | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Fang et al. (2017) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Huang et al. (2022) | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Huang et al. (2023) | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Kang et al. (2017) | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Li et al. (2022) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Lv et al. (2020) | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Magnani et al. (2019) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| McKeown et al. (2022) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Qi et al. (2020) | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Song & Ma (2021) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Zhang et al. (2020) | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ- C30: EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire; EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for cancer patients in palliative care; EORTC QLQ-LC13: EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer; EQ 5D-5L: EuroQol 5-dimensions 5-level; FACT-B: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast; FLIC: Functional Living Index; POS: Palliative Outcome Scale; SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-Item Short Form.

Among the 21 studies included in this review, we did not find any instruments that specifically assess quality of life in relation to PICC, MC and PIVC. The included studies have adapted existing instruments to assess the QoL or have developed specific instruments that require external validation to be reported. There is an opportunity to develop a QOL instrument for PIVC,MC,PICC. Of the findings we have extracted we frame our discussion around 6 areas (i) type of patients in QoL studies, (ii) types of devices in QoL studies, (iii) evidence synthesis on QoL, (iv) standardization of instruments used in QoL studies, (v) moment in which the quality of life is evaluated, and (vi) constructs of the QoL questionnaire or instruments.

Type of patients in QoL studiesThe current state of research on QoL studies reveals a predominant focus on cancer patients. Of the 19 primary studies included in this review 17 studies referred to cancer patients, the remaining 2 studies included palliative care patients. However, the two palliative care studies included cancer patients in their population group. Considering VADs are integral to delivering intravenous chemotherapy45 it is not surprising that most studies included cancer cohorts. While this emphasis has yielded valuable insights, there exists a notable gap in the exploration of QoL in patients with conditions other than cancer. The evidence underscores the importance of evaluating QoL in all patients with VADs irrespective of their specific medical condition. To enhance the breadth of knowledge, future research needs to investigate QoL in individuals with common pathologies or those requiring longer-term treatment. A limitation of this study is that we did not include patients requiring VADs for haemodialysis and from screening identified sources we did note a large number of papers on this patient group. However, there are other patients’ conditions which have not been explored. One example may be patients who are receiving outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT), where at minimum patients receive two doses of parenteral antimicrobial therapy on different days without requiring hospitalisation.46,47 We identified one study which measure health-related quality of life of patients on OPAT however this study did not appear to refer to the patients VAD.48 It is important that we evaluate the quality of life in all patients with PIVC, MC and PICC regardless of clinical condition and to elaborate on the VAD type used. Therefore, future research studies are required to evaluate the quality of life of all patients who require PIVC, MC and PICC for their medical treatments. This inclusive approach aims to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of these VAD types on the quality of life across diverse patient populations.

Types of devices in QoL studiesThe only vascular access device type that was independently evaluated was PICCs (n = 7).28,31,36,38,40,42,49 Different therapies were assessed in connection to PICC and QoL, including Tai Chi36 and cognitive behavioural therapy.42 In an observational study30 and a network meta-analysis,50 several VADs, including PICCs, TIVAD, and NTCs, were examined. Both studies indicated that the TIVAD group had a greater QoL.

The majority of studies comparing the quality of life in PICC versus TIVAD (n = 5) found that the PICC group’s score was significantly lower than the TIVAD group.29,33,37,43 However, one observational study using the EORTC QLQ-C30 tool that included patients with breast and colonic carcinoma found no differences in QOL.34

Regarding PICC versus MC (n = 2), both studies27,32 described a notable increase in the patients’ overall QoL. One prospective observational study39 examined QoL in connection to PICC and TCC in 50 patients. It was shown that there were little statistically significant differences in quality-of-life issues between the patient groups with PICCs and TCCs using a specially designed questionnaire.39

When compared to PIVC, TIVAD significantly enhanced patient-reported quality-of-life benefits in patients receiving chemotherapy for solid tissue malignancies, according to one RCT involving 120 patients undergoing the treatment.35 This contrasts with research comparing quality of life of 130 patients with colorectal cancer based on the device choice (between TIVAD and PIVC), which found no differences in quality of life except from social function.44 An RCT examined the benefits and drawbacks of implanting a TIVAD rather than a PIVC in patients at the start of a chemotherapy regimen to prevent potential peripheral venous access issues.26 Interestingly, in this study there was no discernible difference between TIVAD and PIVC in terms of functional quality of life.

Evidence synthesis on QoLOf the 21 papers included, two were systematic reviews. In one study, out of the fifteen papers included in the study by Robinson et al. on the best vascular access devices for early-stage breast cancer, only three papers (one of which included PIVC) addressed quality of life.41 In one non-randomized comparative study of patients with breast cancer, Singh et al.51 reported chemotherapy administered via PIVC to be acceptable but linked with worse satisfaction in patients receiving more than six treatment cycles as compared to chemotherapy via TIVADs. In the other systematic review and network meta-analysis by Yeow et al.50 QoL was reported in 7 studies. Of these 7 studies, 4 papers included PICC. 3 papers investigated PICC vs PORT33,52,53 and one compared PICC with TIVAD and Hickman.54

Papers with MC devices were not included in the synthesised reviews however, if QoL is an outcome of interest in vascular access research more research is needed on these devices so that they can be included in future synthesis. This review revealed that the term “quality of life” is not used in many studies; instead, it is represented by patient satisfaction or experience. Additionally, some papers do not mention the VAD type even though the patients surveyed required one for therapy, for example oncology care or OPAT. Therefore, to ensure a more thorough synthesis there is a need for standardisation of terminology. Given the number of RCT data located, meta-analysis is justified, however, we suggest first to develop for more evidence on QoL instruments for PIVCs and MCs.

Standardization of instruments used in QoL studiesAdvancements in standardizing instruments for assessing QoL involve the use of established instruments such as the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EQ-5D across various studies.31–35,40,44,50 Standardized instruments serve as a common nomenclature for QoL assessment, aiding healthcare providers with evidence-based decision-making and outcome comparison across diverse patient populations.55 This contributes to a stronger evidence base for comprehending VADs’ impact on QoL. Ongoing efforts are crucial to promoting the consistent use of recognized QoL assessment instruments in studies. Such approaches can facilitate better comparison and synthesis of findings as standardization enhances comparability between studies, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of patient-reported outcomes.56 However, gaps persist due to non-validated use of QoL assessment instruments. This hinders future evidence synthesis and conclusions, as we found no consensus on the optimal tool for specific QoL aspects in the context of VADs we included.30,33,34,39,43,50

Future research avenues should explore the development of tailored instruments for specific patient populations or treatment contexts, maintaining cross-study comparability.57 Additionally, there is a need for instruments assessing the influence of new VADs, for example PICC and PORT, on patients’ QoL, distinguishing its impact from the underlying disease. Such instruments may include considerations of body image change, specific care requirements, and concerns about potential complications beyond those inherent to the pathology.58 To further enrich the research landscape, exploring the feasibility of using modifications or adaptations of existing questionnaires could be particularly interesting.

Moment in which the quality of life is evaluatedIn general, most authors acknowledge the importance of identifying the appropriate moment to measure the quality of life when a catheter is inserted but there is not a consensus related to the most appropriate moment to measure quality of life.

Baseline measurement is necessary in order to know the starting point of the patient who requires intravenous vascular access, before the patient becomes familiar with the catheter, and to measure any changes. It was recognised that it should be close to the moment of insertion31,40 or before the procedure.28,32,36,38,42 However, in some studies this measure was not collected.29,44

Changes in the quality of life may not happen as soon as some authors suggest in their publications (3 days, 14 days). Considering this, there is a need to establish an agreed period to assess the impact of the vascular device in the daily life. Apparently, doing the first measurement three months after inserting the device during the follow-up period could be a reasonable option. However, this may not be enough to collect comprehensive data.

We found no consensus on the timing of measurements beyond three months, as after six to nine months catheter removal could occur and not enough information could be obtained to make longer-term estimates.

If improvement is to occur, an appropriate strategy needs to be defined to identify the correct moment to measure the impact of the VAD type in patients’ quality of life. Specifically, the correct moment to collect baseline measurement and the subsequent moments during follow up period. In addition, it is highly recommended to recognize, anticipate and reduce potential biases that may arise if these measurements are carried out at the same time as the chemotherapy is administered or if it may be affected by patients’ other conditions (patients’ hospital admissions, side effects of treatment, patient's clinical conditions, etc.).

It is essential to consider the extent to which the effects of chemotherapy may affect QoL when measuring the impact of vascular access on quality of life. Hilarius et al. studied chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and found that the prevalence of both was twice as high one week after chemotherapy administration59 and this supports the evaluation of QoL after infusion regimen.

Constructs of the questionnaire/instrumentsAlthough there are studies evaluating the QoL of patients with vascular access, those using validated instruments are scarce. The instruments we have identified in this review are not designed to measure the impact of the device, but rather to measure QoL at a general level with different dimensions and include general aspects for example physical activity, emotional, general well-being, and pain.

In fact, some of the instruments used are generic; they measure QoL in a wide variety of situations, but do not specifically measure aspects relevant to cancer patients. In this study the EuroQol 5-dimensions 5-level (EQ 5D-5L), Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36) have been identified. In contrast, cancer-specific instruments such as the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) and Functional Living Index (FLIC) designed for cancer patients in general have also been identified. Using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and adding a supplement, the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL and the EORTC QLQ-LC13 are specifically designed for use in patients with advanced, incurable, and symptomatic cancer with a median life expectancy of a few months and lung cancer respectively have been used. In addition, an adaptation of another generic questionnaire (FACT-C) for cancer patients with a specific supplement for breast cancer patients (FACT-B) has been used. All these questionnaires report a good level of validity and reliability. On the other hand, there seems to be an interest in the research community in studying the impact of vascular access, as seen in studies that have used ad-hoc designed instruments. However, the instruments need to be further developed and validated as they lack validity and reliability, suggesting VAD related QoL is needed for patients with cancer.

Apart from ad-hoc designed instruments, none of the questionnaires focuses on the impact of vascular access on these patients, so it is not possible to compare which devices have a lower impact on their quality of life. This could be a relevant factor to consider when selecting the most appropriate device for each patient, but this requires validated instruments and studies that compare quality of life with different devices and in different types of patients. Patients’ cohorts could include those with cancer or those needing OPAT.

One of the limitations of this study is that authors often use instruments that assess satisfaction, acceptability or performance to measure the QoL of patients with vascular access. For example, the Karnofsky scale measuring the ability perform ordinary tasks is used as an instrument to measure quality of life. As an implication for future research, the aim of the studies needs to be properly defined and the tool to be used needs to be selected accordingly.

This scoping review identified few QoL studies on three of the most common VADs in use in healthcare. Future instruments for QoL for PIVC, MC and PICC are required and should include patient and public contributions with the variety of healthcare and industry professionals included in any membership.

As the evidence base for vascular access continues to evolve, we suggest this should happen along with patient outcomes influencing best healthcare practice. If this is to be realised we suggest future research should prioritise the impact of VADs on QoL. We recommend the use of validated methodological guidance is required to develop a QoL instrument for PIVC, MC and PICC prior to external validation and implementation amongst different populations and treatment regimes.

FundingThis work was supported by an ENLIGHT partnership grant.

Open Access funding is provided by the University of the Basque Country.

None of the authors has any personal or financial conflicts of interest to declare.