We present the clinical case of an 87-year-old man who presents with chronic prurigo without skin treatment.

The aim is to apply an individualized care plan that allows, based on the latest evidence, to achieve skin integrity, which is deteriorated, and improve its quality of life due to the current failure toad dress the pathology.

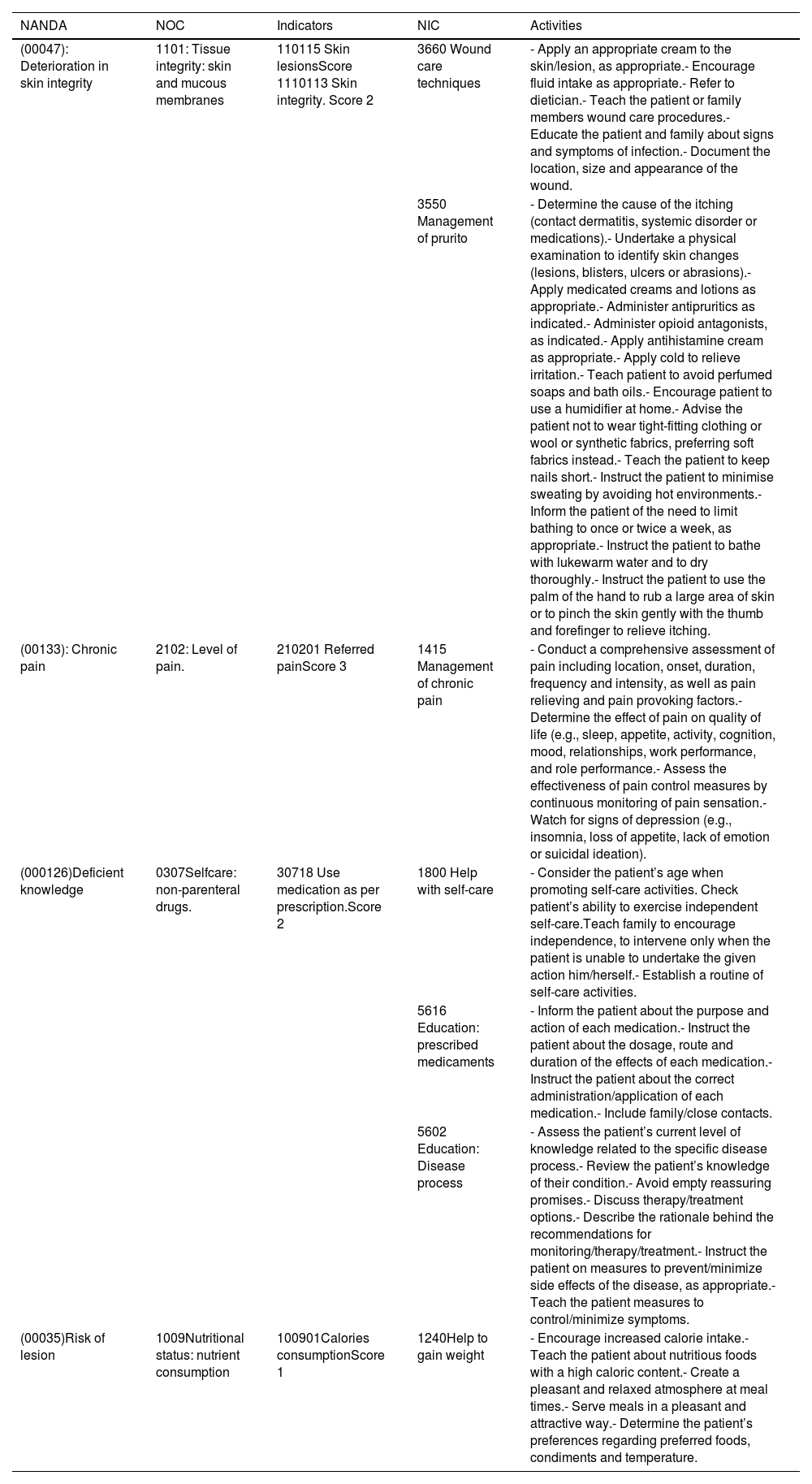

Several NANDA International diagnostic labels were identified using the NNNConsult online tool and the expected outcomes were plan along with the planned nursing interventions.

The care plan shows the intrinsic difficulty of a multifactorial pathology that is little known and rare but that entails a notable impact on the quality of life and skin integrity, especially when new treatment approaches are currently emerging that are un explored by patients and professionals. This situation makes it necessary to expose and train cases like the one presented, update treatment path ways, real involvement of professionals for adaptation, individualization and continuous search to meet the needs and problems suffered by the people we care for, as well as the need to know new skin approaches.

This work outlines a line of skin care that respects skin integrity, following the latest evidence and points out the therapeutic medical approach without going into depth as it is not the aim of the work or nursing competence.

Se presenta el caso clínico de un hombre de 87 años que presenta prurigo crónico sin tratamiento cutáneo.

El objetivo es aplicar un plan de cuidados individualizado que permita, basado en las últimas evidencias, conseguir la integridad cutánea al encontrarse deteriorada y así mejorar su calidad de vida debido al fracaso actual del abordaje de la patología.

Se identificaron varias etiquetas diagnósticas NANDA Internacional utilizando la herramienta online NNNConsult y se planificaron los resultados esperados junto con las intervenciones enfermeras planificadas.

El plan de cuidados muestra la dificultad intrínseca de una patología multifactorial poco conocida y poco frecuente pero que conlleva una notable afectación de la calidad de vida y de la integridad cutánea, cuando además, en la actualidad están emergiendo nuevos abordajes de tratamientos inexplorados por pacientes y profesionales. Esta situación hace necesaria la exposición y formación de casos como el que se presenta, actualización de vías de tratamiento, implicación real de los profesionales para una adaptación, individualización y búsqueda continua para suplir las necesidades y problemas que padecen las personas a las que cuidamos, así como la necesidad de conocer nuevos enfoques cutáneos.

Este trabajo traza una línea de cuidados cutáneos respetuosos con la integridad cutánea, siguiendo las últimas evidencias y señala el abordaje terapéutico médico sin profundizar al no ser el objetivo del trabajo ni competencia de enfermería.

The term chronic prurigo (CP), as a consensus-based concept, did not appear until 2018, when a group of experts from the European Prurigo Project prepared a document which detailed the definition, terminology and classification1 of this condition. This document states that it is “an independent disease defined by the presence of chronic pruritus and multiple localised or generalised pruritic lesions. CP occurs due to neuronal sensitisation to itching, i.e., an amplification of pruritic signalling in the peripheral and central nervous system, and the development of an itch-scratch cycle. CP may be of dermatological, systemic, neurological, psychiatric/psychosomatic, multifactorial or indeterminate origin.”1

It is considered that the prevalence of this pathology has been underestimated, due to the heterogeneity of its aetiology; the way in which pruritus occurs, and the appearance of pruritic lesions (papules and/or nodules and/or scaly, desquamative plaques and/or scabs) and their changes over the course of the disease,2 which poses a challenge in terms of the care provided to people with this condition, thus requiring the need for individualised management.3 The distribution of lesions is usually generalised in areas accessible to scratching; the face, palms of the hands and soles of the feet,2 with the exception of the interscapular area, the central region of the back (“butterfly sign”).

The diagnosis of this condition is based on a detailed clinical history and physical examination where pruritus stands out as a necessary initial symptom. Even so, at times the diagnosis is not so simple and a skin biopsy and/or dermoscopy is required as an additional test.1,2

This is a condition that causes serious deterioration in quality of life, with pruritus, skin lesions and loss of sleep being the most significant aspects that are affected.4

Treatment varies and often requires a multimodal approach: systemic treatment such as Dupilumab, Thalidomide or Pregabalin,5 topical corticosteroids6 and phototherapy,7 among other treatments.

Since the literature basically includes pharmacological approaches, we present a clinical case of a patient with CP without adherence to treatment, where nursing care was proposed.

AimTo develop an individualised care plan for a patient with chronic prurigo, based on the latest evidence, to improve the approach to this pathology and its adherence, as well as optimising the patient’s skin integrity and quality of life.

Case descriptionAn 87-year-old man with no known drug allergies, with multiple pathologies, was admitted due to frank haematuria of 24 hours and impossibility of a 3 lumen probe in his referral hospital, so the patient was transferred to another hospital where catheterisation was undertaken without incident, initiating therapy with continuous bladder lavage and admission to the Urology unit.

Medical history: arterial hypertension, permanent atrial fibrillation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, fracture with crushing of the D11 vertebra, hearing loss with hearing aids, fistulised epidermal cyst in the right arm (removed), pseudopolyglobulia, simple prurigo (since 2016), habitual epistaxis and splenomegaly. The patient was a non-drinker. Cataract surgery was undertaken.

Medication: Fortzaar 100/25 mg, Atenolol 50 mg, Dutasteride 500 mcg, Apixaban 2,5 mg, Alopurinol 300 mg, Omeprazole 20 mg, Digoxin ½ 0,25 mg, Gemfibrozil 900 mg.

The patient lived with his wife, who was his primary caregiver and they received help from an informal caregiver 3 days a week.

Overall ratingUpon admission, a nursing assessment was carried out using Virginia Henderson’s 14 needs. Despite addressing all these needs in collaboration with other health care professionals, this paper focusses on hazard avoidance and skin and mucous membrane hygiene and integrity. As a complement to this assessment, the following were used:

- -

Barthel scale: 90 points (mild dependence).

- -

EMINA scale, obtaining moderate risk (4 points. Mental state: 0; Mobility: 1; Humidity: 0; Nutrition 2; Activity: 1).

- -

MUST scale, with a score over 2 detecting a high risk of malnutrition.

During the performance of a meticulous assessment of the skin, multiple abrasion lesions with hyperpigmented edges were observed, producing intense skin itching and, consequently, scratching, predominantly on the back, and to a lesser extent on both arms (Figs. 1 and 2), legs and initially in one buttock, with continuous bleeding on sheets and nocturnal exacerbation of scratching.

To objectively assess the severity and efficacy of the treatments, the IGA scale (Investigator Global Assessment),8 specific to nodular prurigo, was used, depending on the number of lesions presented by the patient at any given time, from 0 nodules (cleared) to more than 100 (severe), and the Verbal Numerical Scale (VNS), which measures the perception of pain from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable) and the SF-36, which offers an overall perspective of the person’s state of health by addressing different dimensions.

- •

IGA scale: severe.

- •

Verbal numerical scale (VNS): 3.

- •

SF-36 Questionnaire: Physical Function (45/100), Physical Role (0/100); Body Pain (58/100); General Health (25/100); Vitality (35/100); Social Function (88/100); Emotional Role (0/100) and Mental Health (84/100).

After these findings, treatment prescribed by Dermatology and follow-up was reviewed, maximum information was gathered through interviews with the patient and his wife, and a review of the literature was undertaken, in order to adopt the most appropriate and individualised approach.

In his medical history, in October 2015, the patient had presented with pruritus and generalised vesicular scab lesions of two years of evolution. A biopsy had been performed, prescribing as follows:

- •

Prednisone 30 mg in the morning and 15 mg in the evening for one week. Then 30 mg daily in the morning for another week, followed by ¾ of 30 mg until the end of the final week with ¼ of 30 mg.

- •

Apply Fucibet© +20 mg/g +1 mg/g cream to lesions at night (monitor blood pressure).

- •

Apply DK oil. Intense body moisturising lotion from the INTERNATIONAL DERMATOLOGIC PRODUCT laboratory, the main active ingredients of which are ammonium lactate and grape seed oil.

In January 2016, simple prurigo was recorded as a clinical judgment after a study on pruritic bullous dermatosis and biopsy.

After learning of the above and consulting with the patient, he informed us that he had not noticed any improvement, despite notifying his Primary Care (PC) doctor, and had given up any hope of a solution.

Once the nursing assessment had been undertaken, the NANDA diagnostic labels were identified using the NNNConsult online platform as support. The diagnoses identified were as follows:

- •

Deterioration of skin integrity related to inadequate knowledge of the maintenance of tissue integrity manifested by presence of pruritic lesions, pruritus and worn skin.

- •

Chronic pain related to injurious agent manifested by verbalisation and facial expression of pain.

- •

Poor knowledge due to inadequate information on medication and disease process manifested by inappropriate behaviour and incorrect statements on the disease process.

- •

Risk of injury related to decreased physical activity and weight loss.

Based on the diagnostic labels identified, a care plan was developed detailing the expected outcomes (NOC) and the interventions performed (NIC). These are included in the individualised care plan in Table 1, using the online platform NNNConsult, and the quantitative value for each of the outcome indicators was determined according to a 5-point Likert scale.

Patient care plan.

| NANDA | NOC | Indicators | NIC | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (00047): Deterioration in skin integrity | 1101: Tissue integrity: skin and mucous membranes | 110115 Skin lesionsScore 1110113 Skin integrity. Score 2 | 3660 Wound care techniques | - Apply an appropriate cream to the skin/lesion, as appropriate.- Encourage fluid intake as appropriate.- Refer to dietician.- Teach the patient or family members wound care procedures.- Educate the patient and family about signs and symptoms of infection.- Document the location, size and appearance of the wound. |

| 3550 Management of prurito | - Determine the cause of the itching (contact dermatitis, systemic disorder or medications).- Undertake a physical examination to identify skin changes (lesions, blisters, ulcers or abrasions).- Apply medicated creams and lotions as appropriate.- Administer antipruritics as indicated.- Administer opioid antagonists, as indicated.- Apply antihistamine cream as appropriate.- Apply cold to relieve irritation.- Teach patient to avoid perfumed soaps and bath oils.- Encourage patient to use a humidifier at home.- Advise the patient not to wear tight-fitting clothing or wool or synthetic fabrics, preferring soft fabrics instead.- Teach the patient to keep nails short.- Instruct the patient to minimise sweating by avoiding hot environments.- Inform the patient of the need to limit bathing to once or twice a week, as appropriate.- Instruct the patient to bathe with lukewarm water and to dry thoroughly.- Instruct the patient to use the palm of the hand to rub a large area of skin or to pinch the skin gently with the thumb and forefinger to relieve itching. | |||

| (00133): Chronic pain | 2102: Level of pain. | 210201 Referred painScore 3 | 1415 Management of chronic pain | - Conduct a comprehensive assessment of pain including location, onset, duration, frequency and intensity, as well as pain relieving and pain provoking factors.- Determine the effect of pain on quality of life (e.g., sleep, appetite, activity, cognition, mood, relationships, work performance, and role performance.- Assess the effectiveness of pain control measures by continuous monitoring of pain sensation.- Watch for signs of depression (e.g., insomnia, loss of appetite, lack of emotion or suicidal ideation). |

| (000126)Deficient knowledge | 0307Selfcare: non-parenteral drugs. | 30718 Use medication as per prescription.Score 2 | 1800 Help with self-care | - Consider the patient’s age when promoting self-care activities. Check patient’s ability to exercise independent self-care.Teach family to encourage independence, to intervene only when the patient is unable to undertake the given action him/herself.- Establish a routine of self-care activities. |

| 5616 Education: prescribed medicaments | - Inform the patient about the purpose and action of each medication.- Instruct the patient about the dosage, route and duration of the effects of each medication.- Instruct the patient about the correct administration/application of each medication.- Include family/close contacts. | |||

| 5602 Education: Disease process | - Assess the patient’s current level of knowledge related to the specific disease process.- Review the patient’s knowledge of their condition.- Avoid empty reassuring promises.- Discuss therapy/treatment options.- Describe the rationale behind the recommendations for monitoring/therapy/treatment.- Instruct the patient on measures to prevent/minimize side effects of the disease, as appropriate.- Teach the patient measures to control/minimize symptoms. | |||

| (00035)Risk of lesion | 1009Nutritional status: nutrient consumption | 100901Calories consumptionScore 1 | 1240Help to gain weight | - Encourage increased calorie intake.- Teach the patient about nutritious foods with a high caloric content.- Create a pleasant and relaxed atmosphere at meal times.- Serve meals in a pleasant and attractive way.- Determine the patient’s preferences regarding preferred foods, condiments and temperature. |

Information was provided to both the patient and the main caregiver as to other considerations for management of pruritus specific to this pathology, and that could be beneficial, such as paying attention to weather conditions, since warmer weather could increase sweating, skin irritation, increased pH and also thus an increase in pruritus. In winter, preparations in the form of ointment were preferred, while in summer the presentation in the form of cream may be more suitable, since the ointment could cause discomfort with the obstruction of the sweat ducts. It was also reported that different parts of the body may have specific treatment needs.9

The need to carry out non-pharmacological topical interventions for skin care that would promote the skin barrier function of our patient was intensified. These interventions were aimed at treating or preventing dry skin, pruritus and a general improvement in the skin barrier10:

- •

Use of skin cleansers containing amphoteric syndets or surfactants, compared to standard soap and water, as they improve skin dryness.

- •

Use of leave-in lipophilic products containing moisturizers decreased skin dryness and reduced itching.

- •

Choice of products with pH 4 improved the skin barrier.

- •

Formulations containing glycerine and petroleum jelly reduced the incidence of skin tears (STs) that can occur in this type of skin.

In addition to the prescribed treatment, as in the case of STs, where skin fragility is highly significant, and due to their possible similarities, measures could be adopted in the three areas suggested by the International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP)11 to improve skin condition: general health, mobility and the skin itself. Only those that differ and have not been indicated in Table 1 are discussed.

Skin:

- •

Treat dry skin and use an emollient.

- •

Wear protective clothing.

Mobility:

- •

Avoid friction and shear.

General health:

- •

Actively involve the patient and caregiver in care decisions.

- •

Educate the patient and care giver about the risk and prevention of injury.

- •

Protect from self-harm.

- •

Promote a safe environment.

The follow-up on the assessment of results was undertaken in three days, due to the patient’s prompt discharge from hospital as a result of the suspension of continuous lavage therapy and resolution of the haematuria. It was not possible to observe any evident improvement in the outcome indicators once the care plan had been proposed. However, the patient and family were informed of the importance of a further re-evaluation of his pathology, with health care education for both the patient and his main caregiver and a report on the continuity of care was sent to the patient’s referral nurse, also contacting the patient’s PC physician.

The explanation of the interventions included the involvement of the main caregiver, however, we considered it essential to encourage the patient's self-care, this being a treatment objective to aim for, incorporating this into the care routine that the patient required.

DiscussionThe treatment of CP is multimodal and currently ranges from topical treatments (mainly emollients, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, capsaicin, local anaesthetics and antihistamines), combining these with systemic therapies (antihistamines, opioid antagonists/agonists, antiepileptics/neuroleptics, serotonin receptor antagonist, resin, immunosuppressants, immunomodulators, antiemetic drug/antiemetic drug/P substance antagonist, immunosuppressants, antidepressants, phototherapy), in addition to education and psychotherapies. New molecules that could be effective (monoclonal antibodies) are also under development. Similarly, treatment should be tailored specifically to the cause, itch severity, pH, the specific body area, lifestyle, climate, and age.12

Skin care is a fundamental skill in nursing practice. The care strategies adopted in our patient were mainly aimed at education and establishing specific non-pharmacological measures to alleviate some of the complications deriving from the patient’s pathology, such as pruritus and, on the other hand, promoting the skin barrier, avoiding the risk of injury and improving the patient’s knowledge of his pathology. We consider that the need for correct identification and subsequent treatment from the earliest stage of care is essential in order to avoid chronicity and progression of CP as far as possible.

The effect of CP on patients’ quality of life has not been fully elucidated, so that in order to gain insights from patients' experiences and perspectives further research is needed.

Among the main limitations of this study, it should be noted that it was not possible to continue follow up once the care plan had been proposed, so adherence to the treatment regimen and the guidelines given could not be verified, due to discharge resulting from the disappearance of the haematuria.

As a strength, it should be noted that this clinical case provides an update on the care to be undertaken in patients with CP, given that this type of disease and lesion are not very frequent and are unknown to many professionals. This should not imply that the impact caused is downplayed as these patients have the right to evidence-based care so, in that sense, this paper helps to diagnose and approach CP. Updating the approach to this pathology can both assist professionals and also serve as a guide for patients in search of better health and quality of life.

ConclusionsThe assessment of the skin must be holistic and constant regardless of the reason for admission and/or contact with the health system, in order to detect immediate care needs; those that have not yet been addressed; and also to anticipate possible future injuries and their prevention. In older people, especially those with dermatological pathologies, it is particularly important to lay down and promote clear recommendations for skin care in older people, especially those with dermatological pathologies. The focus should not be limited to skin repair and recovery but also to maintaining patients’ overall health, which directly impacts their well-being. Training and awareness are crucial for success in this care and, therefore, in achieving good health outcomes. In addition, it is essential to underline the importance of each professional involved in health care procedures (including auxiliary nursing staff, doctors, nutritionists and physiotherapists, among other specialists) to ensure a complete and multidisciplinary approach to the patient’s well-being, without forgetting the valuable role of caregivers in this process.

Ethical considerationsThe photograph was taken with the consent of the patient and his wife, in addition to obtaining written authorisation for teaching purposes and/or research.

FundingThis work has not received any funding.

Our thanks to the person who has shared their experience of living with this pathology.