This study aimed to identify the association between stereotyping and professional intercollaborative practice.

MethodThis study used a cross-sectional analytical study involving physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and dietitians in a hospital in Jakarta, Indonesia, who were selected using the stratified random sampling method. Data was collected using the Student Stereotypes Rating Questionnaire (SSRQ) and the Assessment of Interprofessional Team Collaboration Scale (AITCS). The stereotyping level was analyzed based on a nine-point SSRQ, while interprofessional collaborative practice was scored based on partnership/shared decision-making, cooperation, and coordination.

ResultsStereotyping was shown to significantly correlate with interprofessional collaborative practice as measured by the SSRQ and AITCS.

ConclusionsPoor interprofessional collaborative practice in subscale partnership/decision-making was dominant. Also, low-rating stereotyping was shown to be dominant with poor interprofessional collaborative practice.

RecommendationThe research recommends that health care providers improve partnership/ decision-making skills for better interprofessional collaboration. For further research, it's recommended to explore another barrier of interprofessional collaborative practice.

Interprofessional collaboration in the workplace is likely to increase health care quality1, achieve nurses’ outcomes1–4, reduce health care cost1, influence patients’ length of stay2, and increase patient safety and patient-centered care (PCC) practice5.

Interprofessional collaborative practice has an obstacle that is referred to as a stereotype. Stereotyping was found to interfere with interprofessional collaboration6,7. Howev er, studies about the association between stereotypes and interprofessional collaboration in the hospital are still rare.

Even though interprofessional collaborative practices in many hospitals at Jakarta are shown in documentation, the opinions from hospitalized patients as costumers of care are still limited. This phenomenon showed that a study exploring the association between stereotypes and interprofessional collaboration was required. This study aimed to identify the association between stereotyping and interprofessional collaborative practice in the hospital. The hypothesis of this study stated that there was an association between stereotyping and interprofessional collaborative practice.

MethodA cross-sectional design was selected to conduct this study using the descriptive-analytic method. Stratified random sampling identified 88 participants consisting of physicians, nurses, nutritionists, and pharmacists in hospital X at Jakarta. Inclusion criteria of this study were a willingness to participate, holding a bachelor's degree (minimum), and being able to stay in the location of the study for the duration of the study.

The instrument of measurement for this research was divided into three parts. Part A was dedicated to participants’ characteristics and consisted of name initials, age, sex, and education level. Part B was used for stereotype measurement, and part C was used for collaborative practice evaluation.

Instrument validation was conducted by the researcher (N = 30). Reliability and validity test results of the stereotyping questionnaire using Cronbach's alpha were 0.987, 0.992, 0.993, and 0.993 for physicians, nurses, nutritionists, and pharmacists, respectively, while it was 0.3061 using the R table. For the collaborative practice questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha showed 0.974, and R table showed 0.3061.

The software was equipped for processing and analyzing data. Univariate and bivariate were carried out to analyze data. Chi-square was used in bivariate analysis.

ResultsThe most prominent age distribution in this study was 21-30 years old (60.2%), followed by 31-40 years old (29.5%), and finally, more than 40 years old (10.2%).

More than half of the participants were female (68.2%), while there were only 28 males (31.8%). Based on education level, the most dominant group of participants were vocational nurses (51 participants or 58%), followed by those with a bachelor's in nursing (14 participants or 15.9%). Next were those with a bachelor's in medicine (8 participants or 9.1%), vocational nutritionists (6 participants or 6.8%), and those with a bachelor's in nutrition (3 participants or 3.4%). The next group in size were vocational pharmacists (3 participants or 3.4%), then those with a bachelor's in pharmacy (2 participants or 2.3%), and one participant with a master's in medicine (1 participant or 1.1%). More than half of the participants (52.3%) had been working for more than four years, while the rest had been working for 1-3 years.

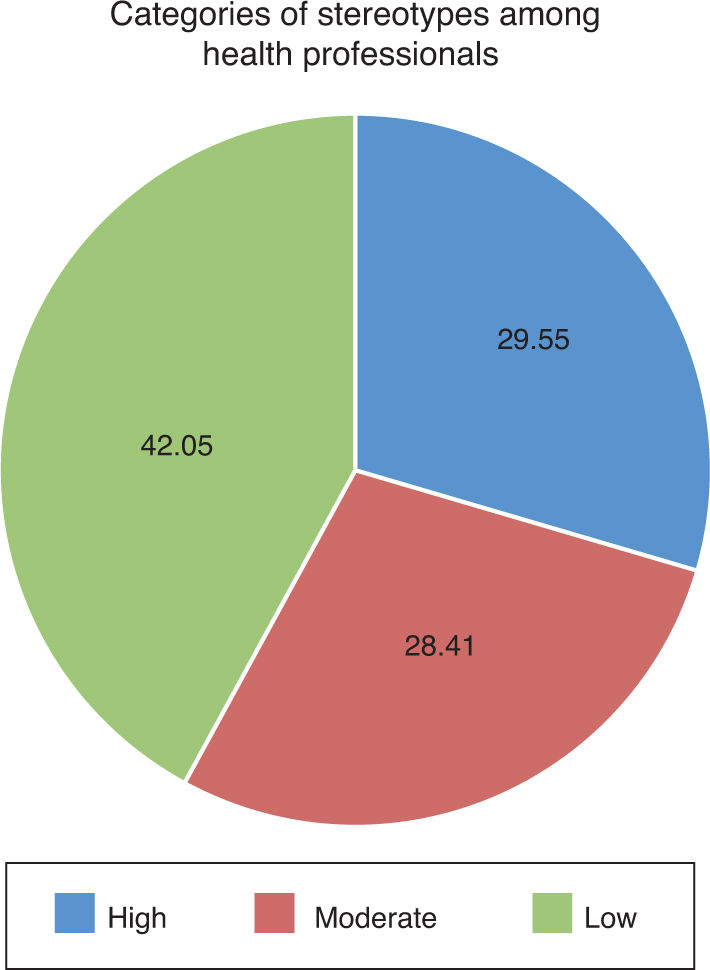

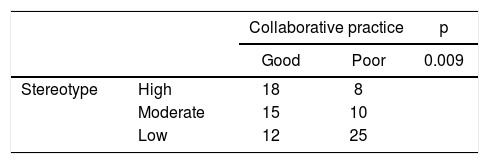

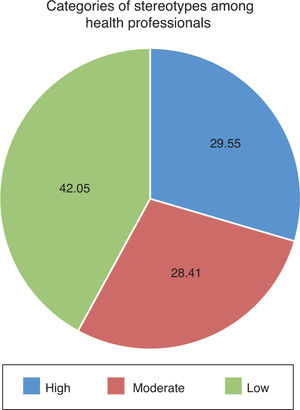

Stereotype distribution in professionals can be seen in Figure 1.

In figure 1, it can be seen that the most dominant stereotype in health care professionals was a low stereotype based on a questionnaire that contained nine components, namely academic skill, professional competence, interpersonal skill (such as compassion, sympathy, and communication), leadership skill, independence, teamwork skill, decision-making skill, practical skill, and trust. Those stereotype levels used the cut of point; > 4 (high), 3.50-3.99 (moderate), and < 3.49 (low)8.

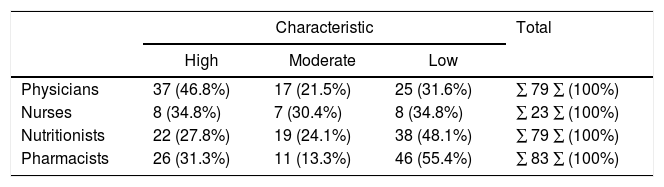

The detail of stereotyping among health professionals (physicians, nurses, nutritionists, and pharmacists) can be seen in Figure 1, which used the cut of point; > 4 (high), 3.50-3.99 (moderate), and < 3.49 (low). Based on that figure, a high stereotype is dominant. This means there are still high or positive stereotypes that exist among health professionals (Table 1).

Stereotypes Toward physicians, Nurses, Nutritionists, and Pharmacists in hospital X, Jakarta, 2016.

| Characteristic | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Moderate | Low | ||

| Physicians | 37 (46.8%) | 17 (21.5%) | 25 (31.6%) | ∑ 79 ∑ (100%) |

| Nurses | 8 (34.8%) | 7 (30.4%) | 8 (34.8%) | ∑ 23 ∑ (100%) |

| Nutritionists | 22 (27.8%) | 19 (24.1%) | 38 (48.1%) | ∑ 79 ∑ (100%) |

| Pharmacists | 26 (31.3%) | 11 (13.3%) | 46 (55.4%) | ∑ 83 ∑ (100%) |

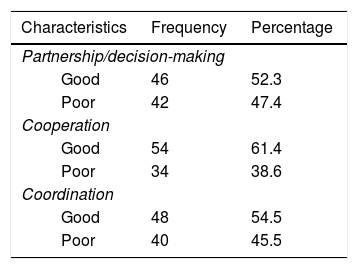

Univariate analysis of collaborative practice evaluated three subscales consisting of partnership/decision-making, cooperation, and coordination. The analysis used the median in the cut of point because of the abnormal data distribution. An analysis of collaborative practice based on three subscales is shown in Table 2.

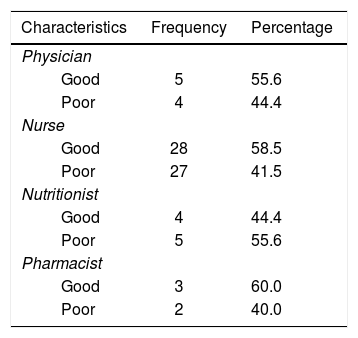

Univariate analysis of collaborative practice was also revealed based on health professionals’ views (physicians, nurses, nutritionists, and pharmacists) in Table 3.

Interprofessional collaborative practice based on physicians, nurses, nutritionists, and pharmacists in hospital X, Jakarta, 2016.

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Physician | ||

| Good | 5 | 55.6 |

| Poor | 4 | 44.4 |

| Nurse | ||

| Good | 28 | 58.5 |

| Poor | 27 | 41.5 |

| Nutritionist | ||

| Good | 4 | 44.4 |

| Poor | 5 | 55.6 |

| Pharmacist | ||

| Good | 3 | 60.0 |

| Poor | 2 | 40.0 |

Besides univariate analysis, bivariate analysis was also performed using the chi-square test. The result showed that there was a significant difference (p = 0.009; α = 0.05). It means that there was an association between stereotyping and interprofessional collaborative practice. The analysis results can be seen in Table 4.

DiscussionParticipant characteristicsThe most dominant age in this study was 21-30 years old, which represented 53 participants. Since these ages are considered to be a productive period, the 21-30's productive period would be a benefit for economy and development9. However, age may trigger stereotypes. Aging employees are assumed to be less productive compared to middle-aged or younger employees10. Chan et al11 revealed that the accuracy of age stereotypes was proven in a study involving 26 countries with 3,000 participants. Furthermore, gender stereotypes were also considered to affect interprofessional collaboration and health care12.

There were 46 participants who had been working as health professionals for more than four years, based on length of work. Mayundarwati13 stated that long periods of working encourage skills and knowledge improvement as well as dedication to the hospital. It can be one indicator that participants in this study might perform better in a collaboration.

Females were the most dominant participant in this study. This was supported by The World Bank14, which stated that the number of female workers significantly increased. However, the female worker only occupied smaller sectors in the work area. Males were considered rational human beings, while females were emotional. Thus, managerial positions were dominated by males. Discrimination in gender stereotypes statistically occurred.

StereotypeA stereotype evaluation in health professionals was conducted in a questionnaire containing nine components, namely academic skill, professional competence, interpersonal skill (such as compassion, sympathy, and communication), leadership skill, independence, teamwork skill, decision-making skill, practical skill, and trust. Studies revealed that negative stereotyping dominated this stereotype category. This corresponds to Macdonald et al; Ateah et al, and Milton and Mandy, which all indicate that stereotyping occurred among health professionals. Macdonald et al15 described the stereotyping by interviewing one of the health professionals. The participant stated that the hierarchy in the hospital where he worked created low stereotypes among health professionals.

The stereotyping of health professionals occurs in some settings in the hospital, such as the surgical ward16. In addition, stereotyping also occurred in a primary health care setting17. Stereotype in a primary health care setting appeared in each of the health professionals.

Results for stereotypes toward physicians, nurses, nutritionists, and pharmacists showed that nurses, nutritionists, and pharmacists held high stereotypes toward doctors. This corresponds to another study conducted by Ateah et al18 that found doctors received high-rating stereotypes in some aspects from other health professionals. In addition, Macdonald et al15 also revealed that physicians had high stereotypes in his qualitative study. Compared to physicians, the nurses were not held to higher stereotypes.

The nurses received the same amount of both high and low stereotypes. Stereotypes of nurses were held by physicians, nutritionists, and pharmacists. Sollami et al19, found that nurses were stereotyped as being less competent than physicians. Nevertheless, another study discovered that nurses received high stereotypes in others aspects, such as teamwork skill and compassion18. Compared to nurses, the nutritionists and pharmacists had lower stereotypes.

Nutritionists and pharmacists had the highest score in poor stereotypes. Stereotypes toward nutritionists were held by nurses, doctors, and pharmacists. Meanwhile, stereotypes toward pharmacists were held by nurses, doctors, and nutritionists. These results were supported by other studies. A study stated that there was a low stereotype toward nutritionists and pharmacists20.

Collaborative practiceCollaborative practice was divided into three subscales: partnership/decision-making, cooperation, and coordination. It showed that the implementation of partnership/decision-making, cooperation, and coordination that supported collaborative practice was still poor in each subscale conducted by nurses, doctors, nutritionists, and pharmacists. In fact, Orchard et al20 revealed that the three subscales were most important in supporting interprofessional collaborative practice21. Coordination is defined as the art of teamwork to achieve an organization's goal in a collaborative way in which there is communication and effective information exchange among health professionals, making it easier to reach equipment. Cooperation occurs when health care professionals work together and share knowledge and skill. Partnership and shared decision-making are as important as the other aspects. Those three components are paramount in collaborative practice. If partnership and shared decision-making were well implemented, then health care options for the patients, negotiation among health professionals, and collaborative team skills would increase.

Identification of inhibiting factors in collaborative practice based on those three subscales is required. It is important to establish interprofessional relationships that affect health care outcomes22. A few studies identified some inhibiting factors in interprofessional collaboration. Some of these stereotype23–25 include culture and, inconsistent language use, inconsistent language use, different language comprehension24,26, different accreditation and curriculum24,26,27, and knowledge of each health professional's role as a member of the collaborative team23,24,27,28. In this study, the researcher discussed one of the inhibitors: stereotyping.

Stereotype and collaborative practiceBased on the statistical test, the results showed that there was an association between stereotypes and interprofessional collaborative practice29. This result was supported by other studies. Sjøvold and Hegstad30 stated that there were different stereotypes among health professionals that caused difficulty in collaborative practice in the hospital. Even though the health professionals were able to work collaboratively with other colleagues, stereotypes may interfere with interprofessional collaborative practice. Several studies indicated that stereotypes were likely to determine interprofessional collaborative practice18,20,22.

LimitationsSeveral limitations were inevitably found in this study. In the preparation period, the researcher had an issue with performing the validation test due to the staff's daily activities. In the implementation stage, the researcher took a longer time in one hospital to gain access for conducting the study. Moreover, the hospital management restricted the amount of participants due to their tight schedule.

One hospital and 88 participants were involved in this study. However, the number or participants was not sufficient to represent each category of health professionals. Therefore, the study could reveal different results in another hospital. In addition, the translation of the instrument was not carried out by a certified translator. It is suggested that a certified translator be employed in future studies.