To analyse the managerial function of school nurses in Spain.

MethodA cross-sectional descriptive study with a sample of 376 school nurses from non-university public, private, and charter educational centres, as well as special education centres nationwide. Data collection was conducted through a self-administered and anonymous questionnaire designed by experts in school nursing, carried out from March to June 2023 via an online platform.

ResultsThe managerial function of school nurses in Spain is evident in their interaction with both educational and healthcare domains. The results underscore the importance of intersectoral collaboration. 96.28% of nurses maintain clinical records. The integration of school nurses into primary care is significantly associated with the service that employs the nurse, contract type, contractual situation, type of educational centre, and membership in rural or socially transformative areas.

ConclusionsSchool nurses play a crucial role in promoting a healthy and safe educational environment. Clinical data recording is essential for monitoring and ensuring care quality. The data highlight the need to implement policies that provide legal assurance for the activities of school nurses and ensure safety for students and the entire educational community.

Analizar la función gestora de la enfermera escolar en España.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo transversal, muestra: 376 enfermeras escolares de centros educativos públicos, concertados o privados no universitarios y centros de educación especial a nivel nacional. Recogida de datos: a través de cuestionario autoadministrado y anónimo diseñado por expertos en enfermería escolar, llevado a cabo, de marzo a junio de 2023, a través de una plataforma online.

ResultadosLa función gestora de las enfermeras escolares en España se pone de manifiesto en la interacción con los ámbitos educativo y sanitario. Los resultados subrayan la importancia de la colaboración intersectorial. El 96,28% de las enfermeras realiza registros en la historia clínica. La integración de la enfermera escolar en Atención Primaria se asocia significativamente con el servicio que contrata a la enfermera, el tipo de contrato, la situación contractual, el tipo de centro educativo, la pertenencia a zona rural y a zonas de transformación social.

ConclusionesLas enfermeras escolares desempeñan un papel crucial en la promoción de un entorno educativo saludable y seguro. El registro de datos clínicos es esencial para el seguimiento y la calidad del cuidado. Los datos ponen de manifiesto la necesidad de implementar políticas que den garantía jurídica a la actividad de la enfermera escolar y seguridad al alumnado y a toda la comunidad educativa.

Despite its proven efficiency in both its recent history and its early days, school nursing is constantly expanding worldwide. The role of school nurses in promoting health and providing preventive and healthcare to students is crucial in an educational setting. They work alongside other healthcare professionals, social services, educational institutions, and families to contribute to the safety and health of school communities.

Research conducted in various international settings has highlighted the decisive role of school nurses in school health management, particularly their ability to collaborate across sectors with primary care, social services, and the educational field.

What does it contribute?This study provides new evidence on the demographic, contractual, and employment profile of school nurses in Spain, emphasising their vital role in health management within schools. The results emphasise the importance of implementing policies that recognise and formalise this role within the education system. This would promote a safe and healthy environment for the entire school community, while also strengthening collaboration with primary care and other institutions in the education and health sectors.

School nurses are key figures and an integral part of the educational system in many countries. They contribute positively to the overall health and academic performance of school-age children and adolescents.1,2 They have a wide range of functions and responsibilities that cover three basic aspects of school health: providing care for acute and chronic health conditions and illnesses; promoting health literacy; and encouraging health promotion. They play a fundamental role in the educational environment, serving as a link between the health and education systems, and contributing to the well-being and academic success of students and staff. In other countries, their work has been shown to be effective in addressing acute and chronic health issues, providing health education, and creating healthier school environments. However, in Spain, the management role of these nurses and their integration into intersectoral collaboration networks has not yet been formally recognised. This study addresses this issue by providing updated data on the role of school nurses in care management and their collaboration with educational and health institutions. These three areas complement each other, all with the common goal of making schools health-promoting environments.3

The European Network of Health Promoting Schools emphasises the importance of a collaborative approach to health promotion in schools in Europe.4 Furthermore, various studies conducted in this context have demonstrated substantial enhancements in health promotion, prevention, and academic performance through school nurses acting as a liaison between education and health systems.5,6

School nurses play a key role among the various professionals who make up the school health services (SSE) in Spain. Their activities include first aid, treating acute and chronic diseases, providing health education, caring for children with special educational needs, and monitoring health.6 These activities have been shown to be cost-effective in preventing obesity, promoting healthy eating, helping people to stop smoking, preventing sexually transmitted infections, and running immunisation programmes.7

In Spain, school nursing is not recognised as a specialty, although the role of the school nurse has been established in some autonomous communities. Current education legislation, Organic Law 3/2020 of 29 December amending Organic Law 2/2006 of 3 May, highlights the promotion and prevention of health in schools in several sections of its text, paying special attention to health education. This includes affective and sexual education, healthy eating habits, the promotion of physical activity, road safety education, and the prevention of traffic accidents. These topics should be incorporated into cross-curricular content,8 but not all schools are managing to implement them. Consequently, they do not meet the criteria for health promoting schools, which may lead to a deterioration in the health of the affected school population.9

The presence of school nurses in schools is considered necessary for the development of educational objectives related to health promotion,4,8 and also as essential personnel to provide care and advice to students with specific health needs.10 In addition, their management role in the planning and implementation of health programmes, coordination and evaluation of the health of the entire school community, including teachers, families, and administrative and service staff is important in order to promote nursing care in a healthy and safe school environment.11

The educational community is currently demanding the inclusion of school nurses as health contact points. For this reason, the Research Group of the National Observatory of School Nursing of the General Council of Nursing of Spain is conducting various studies on their role and its impact on health, addressing knowledge gaps in our context. The research on the management role presented here stands out among these studies. Specifically, this is the first study in Spain to cover all 17 autonomous communities and two autonomous cities, with the aim of determining the profile of school nurses in Spain and analysing their management role in relation to students, health record use in this group, inclusion in the educational community and teaching staff, and interaction with the primary health care service in their geographical area.

MethodDesign, population, and scope of the studyA descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted. The study population consisted of all school nurses working in public, state-subsidised, non-university private, and vocational education centres, nationwide. The 2023 National Observatory of School Nursing reference number of school nurses (N = 2225) was used to collect data from these nurses.

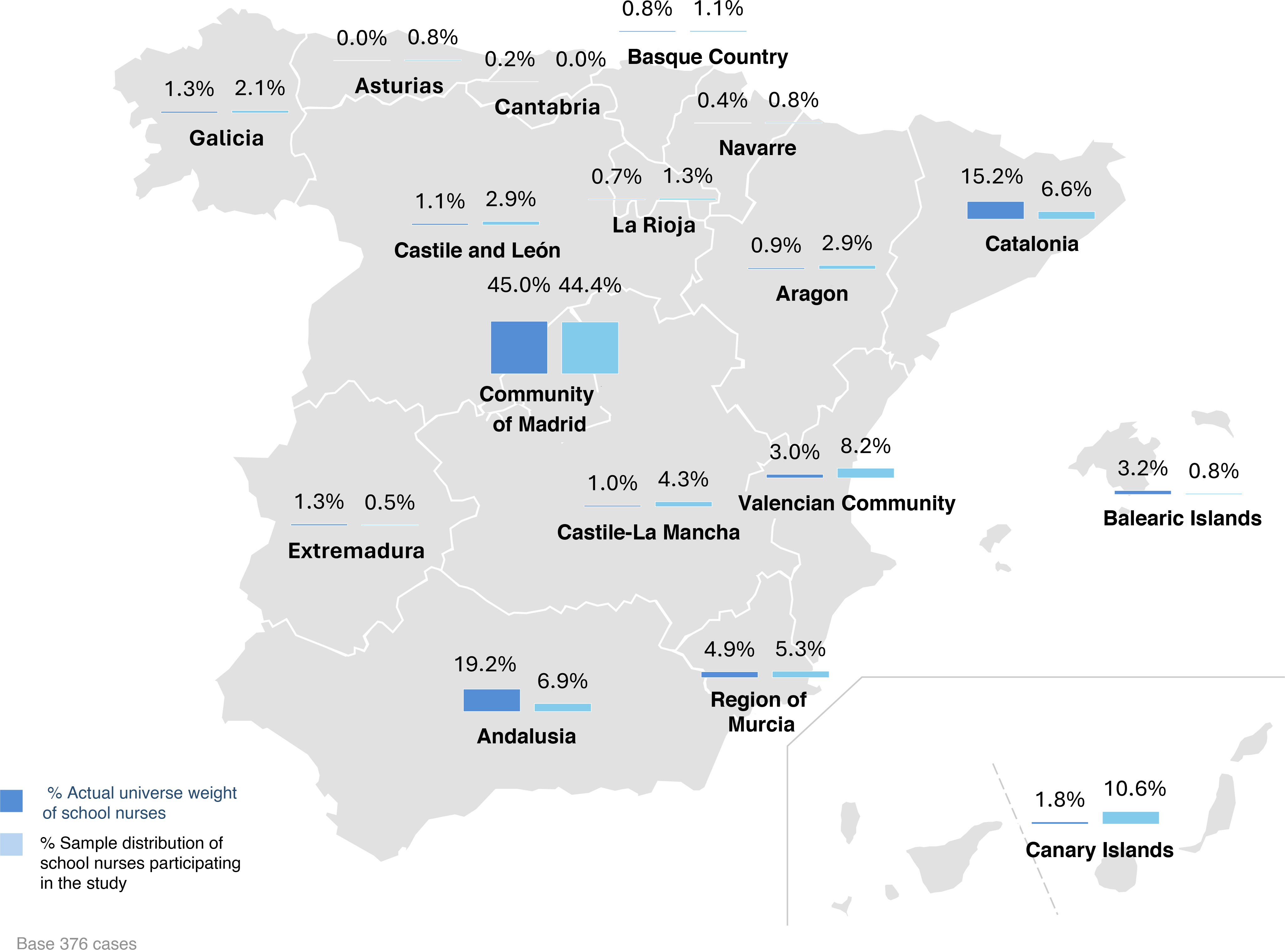

A total of 376 participants were intentionally selected to ensure the inclusion of schools from all regions of Spain (see Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria were being a school nurse, understanding the language, and working in non-university educational centres.

Sociodemographic characterisation of school nurses.

Description of the Figure: The map shows a geographical representation of the percentage of school nurses in blue and the percentage of school nurses participating in the study in light blue. Different autonomous communities are represented, each identified by distinctive colours that reflect different percentages of the actual universe of school nurses and percentages with respect to the distribution of the participating sample.

% Actual universe weight of school nurses; Pantone red 85, green 142, blue 213.

% Sample distribution of school nurses participating in the study; Pantone red 184, green 212 and blue 240.

A self-administered, anonymous questionnaire designed by a group of school nursing experts from the Research Group of the National Observatory of School Nursing of the General Council of Nursing of Spain was used. This group comprises various experts in school nursing with extensive experience of working and conducting research in school settings, as well as university teaching and research staff with experience in nursing and school health. The questionnaire's validity was ensured through a rigorous process involving two focus groups, one of nine school nurses and one of five parent representatives (Parent’s Association), and five individual interviews with head teachers from both public and private schools. The final questionnaire was then reviewed with a panel of experts in school nursing (n = 8) who verified that the questions were clear, relevant, and appropriate for measuring the study objectives. A total of 376 school nurses from all over Spain were selected using convenience sampling to cover the 17 autonomous communities and two autonomous cities.

The questionnaire consisted of 20 questions divided into five sections: 1. Socio-demographic and occupational variables of the school nurses; 2. Variables related to the school; 3. Variables related to interaction with the educational community; 4. Variables related to nurse records; 5. Variables related to interaction with primary care and other institutions (see Appendix A). Prior to the final administration of the questionnaire, a pilot test was conducted to identify potential issues with the wording of the questions and adjust the format based on the participants' comments. The pilot test was conducted with the three groups considered in the study: 9 school nurses, 5 parent representatives, and 5 head teachers. The aim was to determine whether the questionnaire was clear, relevant, and written in understandable language that would allow the objective to be achieved. This enabled the questionnaire to be adjusted before its implementation in the nationwide study. The data collection period was from March to June 2023. The questionnaire was administered in digital format via a web platform and took approximately 20 min to complete.

Data analysisComplete case analyses were undertaken. A descriptive analysis of the sample was performed, using the mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables, and frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. Tests such as the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were also used to compare proportions, when necessary, as well as the ANOVA test. For mean comparison analyses, Student's t-test was used after checking for homoscedasticity of variances using Levene's test. Some variables were recoded to reduce the number of response categories for statistical reasons.

An alpha error probability of <5% (p < .05) and a 95% confidence interval were considered for all analyses.

Descriptive and inferential statistical techniques were used to analyse the data, with R software version 4.0.5 and RCommander version 2.7-1.

Ethical considerationsThe ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki were observed, and the confidentiality of the data was guaranteed in accordance with Organic Law 3/2018 of 5 December on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights. The anonymity of all participants was ensured. They signed an informed consent form and received an information sheet. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias Code CEIm: OE 18/2023.

ResultsThe results provide relevant information on the age, gender, type of contract, and working conditions of the nurses, as well as the characteristics of the schools where they work and their access to student information. The results also highlight the nurses' degree of integration into the educational community. Key aspects are also highlighted, such as the frequency of clinical data recording and relationships with primary care services and other educational and health institutions. This emphasises the importance of management in this area of nursing. The profile of school nurses is compared according to their level of integration into various aspects of care, such as interaction with students, families, and the educational community, as well as integration with primary healthcare.

Sociodemographic characteristicsThe sample comprised a total of 376 nurses, with a mean age of 40.55 (SD 9.22). A total of 94.15% (n = 354) were women, most of whom (76.33%) were employed under the ''exclusive model'' (i.e., continuously employed at the school) and worked full-time (78.72%). Over half of the sample (60.37%) worked as school nurses for the Regional Department of Health or Regional Department of Education, primarily the latter (39.89%). Additionally, 59.31% held permanent or permanent-discontinuous contracts, while 18.09% held temporary contracts; the remainder held other types of contracts. In terms of the characteristics of the school where the school nurse works, 67.82% work in nurseries, primary schools, and/or secondary schools. The majority (60.6%) work in public urban centres (85.9%) with fewer than 500 students (43.2%). These centres are not located in socially transformative areas (81.6%) and attend an average of 20.6 students per day (seeTable 1). It should be noted that, of the nurses interviewed, 96.28% keep nursing records in the clinical history records platform provided by the regional education authority. The majority (94.1%) have access to student information via a file kept at the school (35.3%), and also communicate with families (96.8%). However, they do not belong to the teaching staff or other bodies of the school community (69.1%). Most are not integrated with primary care (63.5%), but have a direct relationship with primary care and/or social services in most cases (37.5%).

Description of the Spanish school nurses participating in the study.

| Variable | n (%)/mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Variables relating to the school nurse | |

| Gender (m.d = 0) | |

| Female | 354 (94.15) |

| Male | 20 (5.32) |

| Non-binary | 2 (.53) |

| Age (m.d = 1) | 40.55 (9.22) |

| Entity overseeing their service/employment (m.d = 0) | |

| Department of Health | 77 (20.48) |

| Department of Education | 150 (39.89) |

| School | 61 (16.22) |

| Private intermediary company | 67 (17.82) |

| Other (local council, Parent’s Association, patient association) | 21 (5.59) |

| Current contract type (m.d = 0) | |

| Permanent | 90 (23.94) |

| Discontinuous permanent | 133 (35.37) |

| Temporary | 68 (18.09) |

| Indefinite | 29 (7.71) |

| Employed for the school year | 32 (8.51) |

| Other (employed for services, covering leave, self-employed) | 24 (6.38) |

| Working hours (m.d = 10) | |

| Reduced-part-time | 70 (19.13) |

| Full-time | 296 (80.87) |

| Contractual status (m.d = 0) | |

| Exclusive model | 287 (76.33) |

| Itinerant model | 51 (13.56) |

| Attending regularly and other | 38 (10.11) |

| Variables relating to the centre | |

| Type of school (m.d = 0) | |

| Pre-school and/or primary | 110 (29.26) |

| Secondary and/or high school | 19 (5.05) |

| Pre-school, primary, and secondary | 145 (38.56) |

| Special education | 67 (17.82) |

| Various types of centres | 35 (9.31) |

| Type of funding (m.d = 0) | |

| Public | 228 (60.64) |

| State-subsidised | 104 (27.66) |

| Private | 44 (11.70) |

| Area where the centre is located (m.d = 0) | |

| Rural | 53 (14.1) |

| Urban | 323 (85.9) |

| Approximate number of students (m.d = 8) | |

| < or = 500 | 159 (43.21) |

| 501−1499 | 145 (39.40) |

| > or = 1500 | 64 (17.39) |

| Socially transformative area (m.d = 50) | |

| Yes | 60 (18.4) |

| No | 266 (81.6) |

| Average number of students attended per day (m.d = 0) | 20.64 (18.65) |

| Variables relating to nurse records | |

| Keeps nursing records (m.d = 0) | |

| Yes | 362 (96.28) |

| No | 14 (3.72) |

| Types of records (m.d = 14) | |

| Clinical history-recording platform provided by the regional health system | 51 (14.09) |

| Clinical history-recording platform provided by the Department of Education | 132 (36.46) |

| Recording platforms created by the nurses themselves, manual or digital (pen and paper, Excel…) | 36 (9.94) |

| Private platforms, free or paid | 37 (10.22) |

| Recording platforms provided by the school itself | 21 (5.80) |

| Other | 85 (23.48) |

| Variables relating to interaction with the educational community (Parent’s Association, parents, head teacher, students…) | |

| Access to student information (m.d = 0) | |

| Yes | 354 (94.15) |

| No | 22 (5.85) |

| --------Means of access to information (m.d = 22) | |

| File kept at the school | 125 (35.31) |

| Clinical history | 69 (19.49) |

| Information provided by teaching staff | 15 (4.24) |

| Information provided by families | 113 (31.92) |

| Other | 32 (9.04) |

| Access to communicate with the family (m.d = 0) | |

| Yes | 364 (96.81) |

| No | 12 (3.19) |

| Belonging to the teaching staff or bodies of the school community (m.d = 0) | |

| Yes | 116 (30.85) |

| No | 260 (69.15) |

| Variables relating to interaction with PC and other institutions | |

| Integration with primary care (m.d = 0) | |

| Yes | 137 (36.44) |

| No | 239 (63.56) |

| Direct relationship/coordination with other institutions (m.d = 0) | |

| Primary care and/or social services | 141 (37.50) |

| Some related to healthcare, social services, and administration (local council, public administration, public health, specialised care) | 55 (14.63) |

| Several related to healthcare, social services, and administration (Primary care, local council, public administration, social services, specialised care) | 128 (34.04) |

| None | 52 (13.83) |

Note: m.d = missing data.

With regard to interaction with students, access to student information is statistically significantly related to a higher mean age of the school nurse, the entity on which their contract depends, higher when they belong to the school, and the contractual status (exclusive model). In addition, access to student information was significantly associated with the type of school where the school nurse works (early childhood, primary, and secondary education), the type of funding of the centre (subsidised and private), and maintaining records (seeTable 2).

Comparison of school nurse profiles based on their interaction with students: access to student information.

| Variables/access to student information | Yes | No | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables relating to the school nurse | |||

| Gender | .134 | ||

| Female | 334 (94.4) | 20 (90.9) | |

| Male | 19 (5.4) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (.3) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Age | 40.77 (9.28) | 36.86 (7.49) | .031 |

| Entity overseeing their service/employment | .027 | ||

| School | 60 (16.9) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Department of Education | 139 (39.3) | 11 (50.0) | |

| Department of Health | 72 (20.3) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Through a private company | 66 (18.6) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Other | 17 (4.8) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Working hours | .207 | ||

| Full-time | 285 (81.4) | 11 (68.8 | |

| Reduced-part-time | 65 (18.6) | 5 (31.2) | |

| Variables relating to the centre | |||

| Contractual status | .001 | ||

| Exclusive model | 275 (77.7) | 12 (54.5) | |

| Itinerant model | 49 (13.8) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Attends the centre regularly and other | 30 (8.5) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Type of school | .000 | ||

| Pre-school and/or primary | 102 (28.8) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Secondary and/or high school | 13 (3.7) | 6 (27.3) | |

| Pre-school, primary, and secondary | 139 (39.3) | 6 (27.3) | |

| Special education | 67 (18.9) | 0 (.0) | |

| Various types of centres | 33 (9.3) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Type of funding | .037 | ||

| State-subsidised | 102 (28.8) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Private | 43 (12.1) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Public | 209 (59.0) | 19 (86.4) | |

| Area where the centre is located | .104 | ||

| Rural | 47 (13.3) | 6 (27.3) | |

| Urban | 307 (86.7) | 16 (72.7) | |

| Approximate number of students | .632 | ||

| < or = 500 | 152 (43.8) | 7 (33.3 | |

| 501−1499 | 135 (38.9) | 10 (47.6) | |

| > or = 1500 | 60 (17.3) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Socially transformative area | .174 | ||

| Yes | 55 (17.7) | 5 (31.2) | |

| No | 255 (82.3) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Average number of students attended per day | 21.03 (18.79) | 14.55 (15.19) | .067 |

| Variables relating to nursing records | |||

| Nursing record | .000 | ||

| No | 8 (2.3) | 6 (27.3) | |

| Yes | 346 (97.7) | 16 (72.7) | |

| Variables relating to interaction with PC and other institutions | |||

| Integration with primary care | .108 | ||

| Yes | 125 (35.3) | 12 (54.5) | |

| No | 229 (64.7) | 10 (45.5) | |

| Direct relationship/coordination with other institutions | .754 | ||

| Primary care and/or social services | 134 (37.9) | 7 (31.8) | |

| Some related to healthcare, social services, and administration (local council, public administration, public health, specialised care) | 53 (15.0) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Several related to healthcare, social services, and administration (primary care, local council, public administration, social services, public health, specialised care) | 119 (33.6) | 9 (40.9) | |

| None | 48 (13.6) | 4 (18.2) | |

In terms of interaction with families, communication with families is statistically significantly related to the contractual status (exclusive model) and working hours (full-time). Furthermore, access to communication with families was significantly associated with the type of school where the school nurse works (early childhood, primary, secondary, and special educational needs centres), the centre's funding (state-subsidised) and not belonging to a socially transformative area (seeTable 3).

Comparison of school nurse profile based on interaction with students: communication with the family.

| Variables/communication with the family | Yes | No | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables relating to the school nurse | |||

| Gender | .083 | ||

| Female | 11 (91.7) | 343 (94.2) | |

| Male | 0 (.0) | 20 (5.5) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (8.3) | 1 (.3) | |

| Age | 40.60 (9.20) | 38.64 (10.01) | .534 |

| Entity overseeing their service/employment | .114 | ||

| School | 60 (16.5) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Department of Education | 147 (40.4) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Department of Health | 72 (19.8) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Through a private company | 66 (18.1) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Other | 19 (5.2) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Working hours | .002 | ||

| Full-time | 293 (81.8) | 3 (37.5) | |

| Reduced-part-time | 65 (18.2) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Variables relating to the centre | |||

| Contractual status | .000 | ||

| Exclusive model | 283 (77.7) | 4 (33.3) | |

| Itinerant model | 49 (13.5) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Attends the centre regularly and other | 32 (8.8) | 6 (50.0) | |

| Type of school | .000 | ||

| Pre-school and/or primary | 107 (29.4) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Secondary and/or high school | 15 (4.1) | 4 (33.3) | |

| Pre-school, primary, and secondary | 144 (39.6) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Vocational education | 66 (18.1) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Various types of centres | 32 (8.8) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Type of funding | .038 | ||

| State-subsidised | 104 (28.6) | 0 (.0) | |

| Private | 43 (11.8) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Public | 217 (59.6) | 11 (91.7) | |

| Area where the centre is located | .073 | ||

| Rural | 49 (13.5) | 4 (33.3) | |

| Urban | 315 (86.5) | 8 (66.7) | |

| Approximate number of students | .128 | ||

| < or = 500 | 154 (43.1) | 5 (45.5) | |

| 501−1499 | 143 (40.1) | 2 (18.2) | |

| > or = 1500 | 60 (16.8) | 4 (36.4) | |

| Socially transformative area | .002 | ||

| Yes | 54 (17.1) | 6 (54.5) | |

| No | 261 (82.9) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Average number of students attended per day | 20.88 (18.59) | 13.67 (19.91) | .241 |

| Variables relating to school nursing records | |||

| Nursing records | .069 | ||

| No | 12 (3.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Yes | 352 (96.7) | 10 (83.3) | |

| Variables relating to interaction with PC and other institutions | |||

| Integration with primary care | .131 | ||

| Yes | 130 (35.7) | 7 (58.3) | |

| No | 234 (64.3) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Direct relationship/coordination with other institutions | .780 | ||

| Primary care and/or social services | 135 (37.1) | 6 (50.0) | |

| Some related to healthcare, social services, and administration (local council, public administration, public health, specialised care) | 54 (14.8) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Several related to healthcare, social services, and administration (primary care, local council, public administration, social services, public health, specialised care) | 125 (34.3) | 3 (25.0) | |

| None | 50 (13.7) | 2 (16.7) | |

Finally, in relation to interaction with the rest of the educational community, being included in the teaching staff or bodies of the school community is statistically significantly related to contractual status (itinerant model) and working hours (full-time). In addition, access to student information was significantly associated with the type of school where the school nurse works (mainly in special education), the type of funding of the centre (private), and whether the school nurse's role is integrated with primary care (seeTable 4).

Comparison of school nurse profile based on their interaction with students: inclusion in the teaching staff or bodies of the school community.

| Variables/inclusion in the teaching staff or other bodies of the school community | Yes | No | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables relating to the school nurse | |||

| Gender | .166 | ||

| Female | 108 (93.1) | 246 (94.6) | |

| Male | 6 (5.2) | 14 (5.4) | |

| Non-binary | 2 (1.7) | 0 (.0) | |

| Age | 41.86 (9.41) | 39.97 (9.09) | .071 |

| Entity overseeing their service/employment | .321 | ||

| School | 20 (17.2) | 41 (15.8) | |

| Department of Education | 38 (32.8) | 112 (43.1) | |

| Department of Health | 30 (25.9) | 47 (18.1) | |

| Through a private company | 21 (18.1) | 46 (17.7) | |

| Other | 7 (6.0) | 14 (5.4) | |

| Working hours | .002 | ||

| Full-time | 104 (90.4) | 192 (76.5) | |

| Reduced-part-time | 11 (9.6) | 59 (23.5) | |

| Variables relating to the centre | |||

| Contractual status | .017 | ||

| Exclusive model | 90 (77.6) | 197 (75.8) | |

| Itinerant model | 21 (18.1) | 30 (11.5) | |

| Attends the centre regularly and other | 5 (4.3) | 33 (12.7) | |

| Type of school | .000 | ||

| Pre-school and/or primary | 23 (19.8) | 87 (33.5) | |

| Secondary and/or high school | 2 (1.7) | 17 (6.5) | |

| Pre-school, primary, and secondary | 47 (40.5) | 98 (37.7) | |

| Vocational education | 34 (29.3) | 33 (12.7) | |

| Various types of centres | 10 (8.6) | 25 (9.6) | |

| Type of funding | .004 | ||

| State-subsidised | 32 (27.6) | 72 (27.7) | |

| Private | 23 (19.8) | 21 (8.1) | |

| Public | 61 (52.6) | 167 (64.2) | |

| Area where the centre is located (m.d = 0) | .597 | ||

| Rural | 18 (15.5) | 35 (13.5) | |

| Urban | 98 (84.5) | 225 (86.5) | |

| Approximate number of students | .360 | ||

| < or = 500 | 55 (48.7) | 104 (40.8) | |

| 501−1499 | 41 (36.3) | 104 (40.8) | |

| > or = 1500 | 17 (15.0) | 47 (18.4) | |

| Socially transformative area | .585 | ||

| Yes | 17 (16.7) | 43 (19.2) | |

| No | 85 (83.3) | 181 (80.8) | |

| Average number of students attended per day | 21.84 (20.25) | 20.11 (17.90) | .428 |

| Variables relating to school nurse records | |||

| Nursing records | .437 | ||

| No | 3 (2.6) | 11 (4.2) | |

| Yes | 113 (97.4) | 249 (95.8) | |

| Variables relating to interaction with PC and other institutions | |||

| Integration with primary care | .013 | ||

| Yes | 53 (45.7) | 84 (32.3) | |

| No | 63 (54.3) | 176 (67.7) | |

| Direct relationship/coordination with other institutions | .000 | ||

| 1. Primary care and/or social services | 37 (31.9) | 104 (40.0) | |

| 2. Some related to healthcare, social services, and administration (local council, public administration, public health, specialised care) | 16 (13.8) | 39 (15.0) | |

| 3. Several related to healthcare, social services, and administration (primary care, local council, public administration, social services, public health, specialised care) | 57 (49.1) | 71 (27.3) | |

| 4. None | 6 (5.2) | 46 (17.7) | |

With regard to factors related to the integration of school nurses into primary care, a statistically significant association was observed with the service employing the nurse; it is more frequent when the nurse is employed by the Regional Department of Health rather than by other entities, a contractual status that follows the itinerant model or attending the centre on an ad hoc basis, those who work with several types of centres, in public centres, belonging to rural areas, and socially transformative areas. Nurses integrated into primary care work with a lower average number of students. In addition, they mainly access information through clinical records, and more belong to the teaching staff or other bodies of the school community (seeTable 5).

Comparison of the profile and management role of school nurses based on their degree of integration with primary healthcare (PC).

| Variables/integration with PC | Yes | No | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables relating to the school nurse | |||

| Gender | .545 | ||

| Female | 127 (92.7) | 227 (95.0) | |

| Male | 9 (6.6) | 11 (4.6) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (.7) | 1 (.4) | |

| Age | 40.80 (9.14) | 40.40 (9.28) | .691 |

| Entity overseeing their service/employment | <.000 | ||

| School | 12 (8.8) | 49 (20.5) | |

| Department of Education | 24 (17.5) | 126 (52.7) | |

| Department of Health | 77 (56.2) | 0 (.0) | |

| Through a private company | 13 (9.5) | 54 (22.6) | |

| Other | 11 (8.0) | 10 (4.2) | |

| Working hours | .240 | ||

| Full-time | 111 (84.1) | 185 (79.1) | |

| Reduced-part-time | 21 (15.9) | 49 (20.9) | |

| Variables relating to the centre | |||

| Contractual status | <.000 | ||

| Exclusive model | 63 (46.0) | 224 (93.7) | |

| Itinerant model | 42 (30.7) | 9 (3.8) | |

| Attends the centre regularly and other | 32 (23.4) | 6 (2.5) | |

| Type of school | <.000 | ||

| Pre-school and/or primary | 37 (27.0) | 73 (30.5) | |

| Secondary and/or high school | 5 (3.6) | 14 (5.9) | |

| Pre-school, primary, and secondary | 38 (27.7) | 107 (44.8) | |

| Vocational education | 26 (19.0) | 41 (17.2) | |

| Various types of centres | 31 (22.6) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Type of funding | .001 | ||

| State-subsidised | 32 (23.4) | 72 (30.1) | |

| Private | 7 (5.1) | 37 (15.5) | |

| Public | 98 (71.5) | 130 (54.4) | |

| Area where the centre is located | .018 | ||

| Rural | 27 (19.7) | 26 (10.9) | |

| Urban | 110 (80.3) | 213 (89.1) | |

| Approximate number of students | .533 | ||

| < or = 500 | 61 (46.9) | 98 (41.2) | |

| 501−1499 | 49 (37.7) | 96 (40.3) | |

| > or = 1500 | 20 (15.4) | 44 (18.5) | |

| Socially transformative area | .012 | ||

| Yes | 30 (25.6) | 30 (14.4) | |

| No | 87 (74.4) | 179 (85.6) | |

| Average number of students attended per day | 12.69 (14.50) | 25.21 (19.25) | <.000 |

| Variables relating to nursing records | |||

| Keeps school nursing records | .396 | ||

| No | 7 (5.1) | 7 (2.9) | |

| Yes | 130 (94.9) | 232 (97.1) | |

| Variables related to interaction with the educational community (Parent’s Association, parents, head teacher, students…) | |||

| Access to student information | .108 | ||

| Yes | 125 (91.2) | 229 (95.8) | |

| No | 12 (8.8) | 10 (4.2) | |

| Means of access to information | .000 | ||

| File kept at the school | 24 (17.5) | 101 (42.3) | |

| Clinical history | 40 (29.2) | 29 (12.1) | |

| Information provided by teaching staff or families | 3 (2.2) | 12 (5.0) | |

| File of the centre and clinical history | 53 (38.7) | 60 (25.1) | |

| Various and other | 5 (3.6) | 27 (11.3) | |

| Access to communicate with the family | .109 | ||

| Yes | 130 (94.9) | 234 (97.9) | |

| No | 7 (5.1) | 5 (2.1) | |

| Belonging to the teaching staff or other bodies of the school community | .013 | ||

| Yes | 53 (38.7) | 63 (26.4) | |

| No | 84 (61.3) | 176 (73.6) | |

The study provides a comprehensive description of the management role of school nurses in Spain, highlighting their contractual profile, clinical record-keeping practices, and interaction with the educational and healthcare sectors, particularly in the context of intersectoral collaboration with primary care and other services.

The management role of school nurses shows clear dependence on the contracting entities, mostly linked to the Regional Departments of Education and Health, which highlights the need for coordination between sectors for efficient school health management. This integrated working model, promoted in other countries with good results, faces challenges in Spain due to the diversity of contracts and work structures. The international literature supports the effectiveness of school nursing in settings where multidisciplinary collaboration is promoted, including primary care, social services, and local communities.12–14 This study reinforces the importance of policies that recognise the role of school nurses in comprehensive healthcare and in improving connectivity between education and health systems.

The analysis of working conditions reveals that the type of contract and working hours determine nurses’ integration into the school environment and access to information about students and their families. Nurses with full-time, exclusive contracts are better able to communicate with the educational community and integrate into the school structure than those working part-time. This finding is consistent with previous research which has highlighted the impact of working conditions on nurses' ability to perform educational and care functions effectively. Furthermore, including school nurses in digital clinical data recording is an important advance in health information management. Our results show that a high percentage of nurses record their care activities on digital platforms, which is essential for monitoring students with specific health needs and for the early detection of emerging health problems. Adopting digital clinical data recording aligns with the international trend of systematic, evidence-based documentation, facilitating the creation of protocols and optimising healthcare in school settings.15,16

The bivariate analysis revealed that the integration of school nurses into primary care is significantly associated with the type of contract and the contracting entity. It is noteworthy that nurses employed by the Department of Health and those with more flexible working models (such as itinerant) show greater integration into primary care, which may reflect how contractual structures and employment policies influence intersectoral collaboration.17 However, belonging to special education centres and private funding were associated with greater inclusion in the teaching staff and other bodies of the school community.18 This finding may indicate a greater appreciation of school nursing services in settings where health needs may be more complex and varied, such as special education centres, where the importance of integrating nurses into educational structures to enhance health cooperation is highlighted.15,16,19–21

With regard to interaction with students, families, and the rest of the educational community, it was observed that access to student information and communication with families are associated with certain characteristics of the contract and the working environment, such as the exclusivity model and full-time work. This suggests that working conditions are essential for nurses to play an integral role within the educational community, in line with the existing literature, which shows that the level of coordination with other institutions can vary depending on the employer and the school nurse's employment status.16 In relation to this statement, the analysis of the variables shows that part-time work can limit communication with families, suggesting that less presence in the school reduces opportunities for interaction.

With regard to the interaction of nurses with primary care, we observe that integration is more frequent in centres with greater health needs, such as those located in rural or socially transformative areas. This could be due to the urgent need to strengthen healthcare in these environments, where resources are often limited and school nurses can fill important gaps in care. This finding highlights the importance of integration policies and reinforces the need for government support to ensure that school nurses can work effectively in all geographical areas, especially the most vulnerable.

International studies highlight the role of school nurses in health management, emphasising their ability to work across sectors with primary care and community entities such as social services and local councils.22,23 These synergies, together with effective communication with the educational community, are essential for effective and multidimensional school health management.12–15

A study of 2393 teachers highlighted the healthcare needs perceived by teachers in relation to the health of their students, justifying the need for nurses in schools and emphasising their important role in prevention, promotion, and health education.24

With regard to the recording of school nursing care activities and their adaptation to digital platforms, there is a parallel with the evolution towards evidence-based practices and efficient information management, in line with modern trends in health management. The use of advanced technologies in nursing documentation facilitates the early identification of patterns of hyperfrequent use and other health problems that often go unnoticed. This approach allows for detailed analysis and the creation of specific protocols for the early detection of such problems.21,25,26 In this regard, our results show a high percentage of school nurses who keep records, indicating a strong practice in clinical documentation, which is extremely important for monitoring and the quality of student care, especially for students with chronic conditions. However, access to information and communication with families is also influenced, once again, by contractual factors and the type of school.

Finally, the results of this study should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. The sample was selected for convenience and is not representative in the context of school nurses in Spain. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design does not allow for control of the time factor and observation of its influence on the findings, but it does facilitate access to specific populations such as school nurses. Although the study included a representative sample from the 17 autonomous communities and 2 autonomous cities, the use of this type of sampling may introduce bias in the selection of participants. Although it limits generalisation, this approach was chosen for its feasibility in terms of resources and time, determined from an estimated population of 2225 school nurses nationwide.

The questionnaire was conducted ad hoc, although it was developed by experts in school nursing and adjusted through a pilot process. It is an instrument designed specifically for this study, which may limit the comparability of the results with other research studies, and its content was subsequently validated. Despite its limitations, this study has several strengths. It is the first study conducted in Spain and represents an important first step towards understanding the profile and needs of school nurses in Spain. It has provided a profile of school nurses, as well as their management role and interaction with the educational community and health centres.

This study highlights the complexity and importance of the management role of school nurses in Spain, demonstrating their central role in promoting a healthy and safe educational environment.27 Intersectoral collaboration, effective information management, and integration into the educational community are essential to optimise their impact on student health. The findings reinforce the need for supportive policies that recognise and enhance the role of school nursing in the education system, promoting the comprehensive health of students.

This study also contributes to providing a comprehensive overview of the school nurse in Spain, highlighting the need for their effective integration into schools and interaction with the educational community, as it not only influences school health management but also has a direct positive impact on schoolchildren's safety.18,28–30 However, our research suggests that the ability of school nurses to perform these roles may be affected by several factors, such as job stability, type of working hours, type of contract, type of centre and the contracting entity.

This study suggests that school nurses play a critical role in health management within the educational environment. This role should be supported by robust policies that promote job stability and encourage intersectoral collaboration. Although the nature of the sampling and its cross-sectional design limit the generalisation of these findings, this study represents an important first step towards understanding the profile and needs of the school nurse in Spain, providing a basis for future research and policy in this area.

CRediT authorship contribution statement- (1)

Study conception and design: AMVM; DGM; TDP; ASE; JAZE; IHC; MLS;LTC. Data acquisition: AMVM; DGM; TDP; ASE; JAZE; IHC;MLS;LTC. Data analysis and interpretation: AMVM, LTC, TDP.

- (2)

Drafting of the article: LTC, DGM, ASE AMVM, TDP. Critical review of intellectual content: AMVM; DGM; TDP; ASE; JAZE; IHC;MLS;LTC

- (3)

Final approval of the version presented: AMVM; DGM; TDP; ASE; JAZE; IHC;MLS;LTC.

This study has received funding subject to the budgets of the General Council of Nursing of Spain under the heading "Apoyo a la Investigación (Support for research)" for data collection and publication.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank all the school nurses who participated in the study and the Spanish Institute for Nursing Research, General Council of Nursing of Spain, for their support, resources, and funding to conduct the research. We would like to thank Guadalupe Fontán, Coordinator of the Spanish Institute for Nursing Research, Consejo General Council of Nursing of Spain, Diego Ayuso Murillo, Secretary General of the General Council of Nursing of Spain, and Jesús Ibáñez Milla, Deputy Director General of Statistics and Studies. Technical General Secretariat. Ministry of Education and Vocational Training.