Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been available in Spain since November 2019 and implemented nationally in 2021. Monitoring the implementation process is essential to optimize the strategy. This manuscript describes the Spanish PrEP Programme Information System (SIPrEP), its methodology, and characteristics of PrEP users from November 2019 to May 2024.

MethodsNationwide open cohort that collects data on persons ≥16 years who were prescribed PrEP in Spain. The study included participants with public program PrEP prescriptions since November 1, 2019. The project was piloted and fully implemented in July 2020.

ResultsBy May 2024, 28,798 people received public program PrEP in Spain, and 4159 users were included in SIPrEP. Most were men (99%, n=4117), primarily gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) (97%, n=4005), with a median age of 36 years (IQR: 30–43). Most were born in Spain (74%, n=3075), and 36% (n=1503) had university education. Referrals came from STI centers (19%, n=805) and primary care (20%, n=820). At entry, 8% (n=348) had syphilis, 7% chlamydia (n=270) and 7% (n=300) had gonococcal infection. Among users, 15% (n=642) discontinued PrEP, and 34% (n=216) of them restarted later. There were four HIV seroconversions (incidence 0.12/100 person-years [95% CI: 0.05–0.33]).

ConclusionsSIPrEP provides valuable real-world data for optimizing interventions but requires improved national coverage.

La profilaxis preexposición (PrEP) está disponible en España desde noviembre de 2019 e implantada a nivel nacional en 2021. La monitorización del proceso de implementación es esencial para optimizar la estrategia. Este manuscrito describe el Sistema de Información del Programa Español de PrEP (SIPrEP), su metodología y las características de los usuarios de PrEP desde noviembre de 2019 hasta mayo de 2024.

MétodosCohorte abierta de ámbito nacional que recoge datos sobre personas ≥16 años que han iniciado PrEP en España. El estudio incluyó a participantes con prescripción de PrEP en programas públicos desde el 1 de noviembre de 2019. El proyecto se puso a prueba y se implementó completamente en julio de 2020.

ResultadosEn mayo de 2024, 28.798 personas recibieron PrEP del programa público en España, y 4.159 usuarios fueron incluidos en SIPrEP. La mayoría eran hombres (99%, n=4117), principalmente gais, bisexuales y otros hombres que tienen sexo con hombres (97%, n=4005), con una mediana de edad de 36 años (IQR: 30-43). La mayoría habían nacido en España (74%, n=3075), y el 36% (n=1503) tenían estudios universitarios. Las derivaciones procedían de centros de ITS (19%, n=805) y de atención primaria (20%, n=820). Al ingreso, el 8% (n=348) tenía sífilis, el 7% clamidia (n=270) y el 7% (n=300) infección gonocócica. Entre los usuarios, el 15% (n=642) interrumpió la PrEP, y el 34% (n=216) de ellos la reinició más tarde. Se produjeron cuatro seroconversiones del VIH (incidencia 0,12/100 personas-año [IC 95%: 0,05-0,33]).

ConclusionesSIPrEP proporciona datos valiosos del mundo real para optimizar las intervenciones, pero requiere una mejora de la cobertura a nivel estatal.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an HIV prevention strategy based on antiretroviral drugs. PrEP is safe, effective and cost-effective.1–4 PrEP implementation has considerably impacted reducing new HIV infections.5,6 In Spain, between 2018 and 2023 the number of new yearly HIV diagnoses went from near 4000 to around 3000,7 far from the UNAIDS target of reducing new infections by 75% by 2020. Therefore, additional measures, such as PrEP are deemed necessary.8,9

Spain introduced full public reimbursement for PrEP with tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine in the National Health System on 1st November 2019. PrEP is provided free of charge to those meeting the criteria set out in the Spanish Guidelines10: gay, bisexual, or other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), transgender, female sex workers, and, from 2021, men and women ≥16 years old reporting high-risk behaviour for HIV infection and people who inject drugs. In Spain, antiretroviral drugs are prescribed exclusively through hospital pharmacies. PrEP programmes are managed by specialised hospital units and some STI clinics or community centres linked to hospital pharmacies.11

Monitoring real-life PrEP outcomes is essential to measure its impact and identify potential barriers to equitable access for all people who require it; the Spanish PrEP Programme Information System (SIPrEP) serves this purpose. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control12 and the World Health Organisation13 highlight the need for monitoring from a public health perspective. As of May 2024, 28,798 people were estimated to be receiving PrEP in Spain, according to aggregate data provided by the Autonomous Regions to the Ministry of Health.14 This article describes the methodology, implementation of SIPrEP, and the baseline characteristics of PrEP users after its implementation.

MethodsSIPrEP was designed by the Division for the Control of HIV, STIs, Viral Hepatitis, and Tuberculosis (Ministry of Health) in collaboration with the HIV Surveillance Unit and the Cohort Coordination Unit of the Spanish AIDS Research Network (CoRIS) of the Carlos III Health Institute. The process involved the Autonomous Regions and the Spanish Interdisciplinary AIDS Society (SEISIDA).

Study designSIPrEP is an open-label, prospective, multicenter cohort study with a nationwide scope. The platform was piloted in June 2020 by health professionals from hospitals, STI clinics, and community centers with PrEP programs in place or near implementation, and launched on July 29, 2020. Data from participants who started PrEP since its implementation (November 1, 2019) to the SIPrEP launch were introduced retrospectively. The SIPrEP cohort remains open and participation is voluntary. The study period for this work goes from November 1, 2019 until May 31, 2024. Data from centers in Andalusia, Aragon, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Castile-La Mancha, Castile and León, Valencian Community, Region of Murcia, Navarre, Basque Country, Melilla were included. Participating sites are listed in Annex I (supplementary material).

Inclusion criteriaInclusion criteria include having received a PrEP prescription as part of a public programme as of the 1st of November 2019 and having given informed consent.

Objectives and outcome measuresThe main objective of SIPrEP is to monitor the characteristics of PrEP users in public PrEP programs and to provide a tool for monitoring PrEP implementation in Spain. Another goal – through the SIPrEP web platform – is to increase awareness among potential PrEP candidates and healthcare professionals. Here, we report on baseline socio-demographics, behaviors, STI prevalence, and PrEP patterns. We describe reported PrEP discontinuations at 54 months, reasons for discontinuation, and the cumulative incidence of HIV seroconversions on SIPrEP.

Study proceduresParticipants meeting inclusion criteria are assigned a pseudo-anonymised identification code. There is no fixed visit structure; visits are scheduled according to clinical criteria and subject behaviour but the aim is to follow to three monthly visits recommended in the National PrEP Guidelines.10 For operational purposes, three types of visits have been defined: (1) initial visit, where participants receive the first PrEP prescription; (2) follow-up visit, where possible discontinuation of PrEP is recorded; and (3) reinitiation visit, where participants receive a new PrEP prescription after a previous discontinuation. Discontinuation was defined as the deliberate discontinuation of PrEP intake by the participant since the last visit, missing follow-up visits for more than 6 consecutive months, or PrEP discontinuation indicated by the professional due to contraindications.

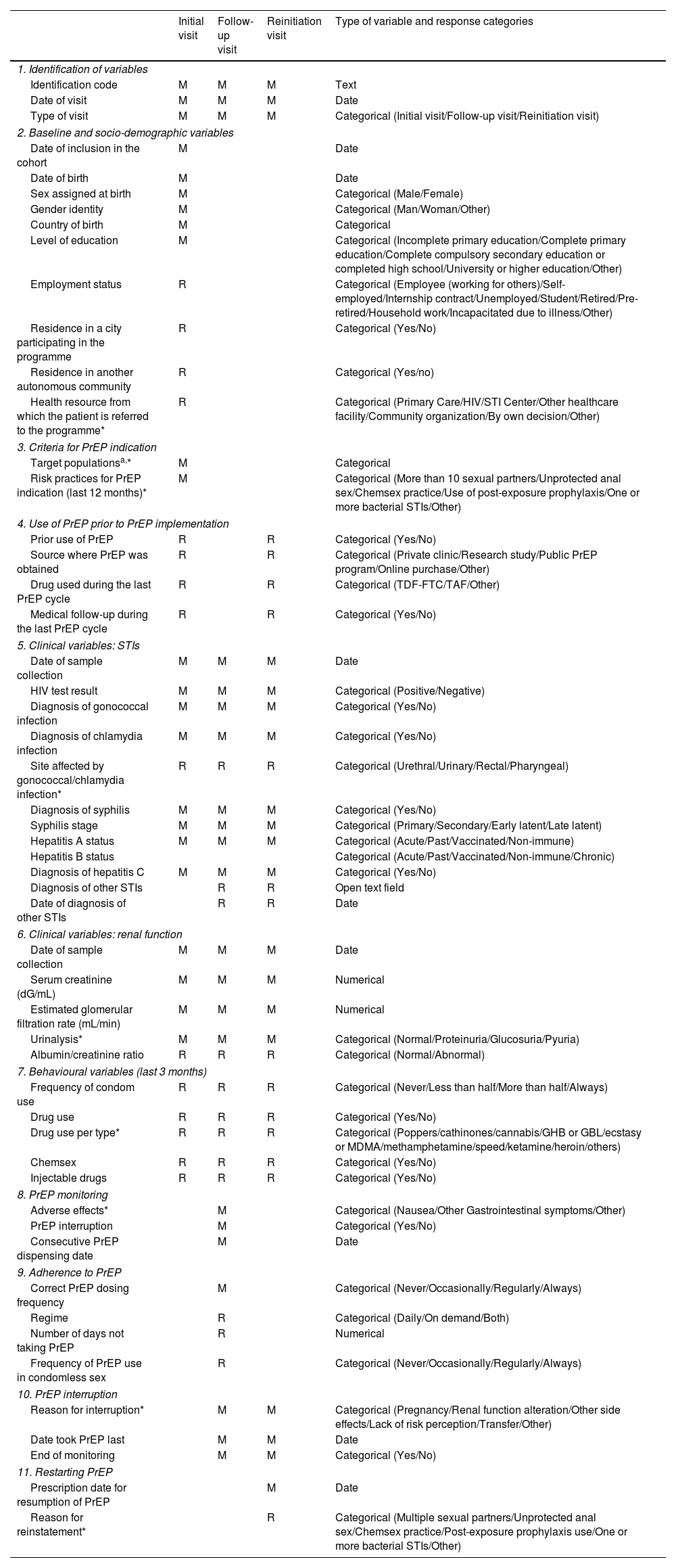

VariablesThe variables were selected and defined taking into account the structure of PrEP programmes, the Guidelines for PrEP Implementation,15 the national implementation study11 and a review of other PrEP and HIV cohorts.16–18 A closed definition of chemsex was not provided; it was left to the clinical judgement of doctors taking care of PrEP users in SIPrEP. The variables are described in Table 1.

SIPrEP variables by visit type.

| Initial visit | Follow-up visit | Reinitiation visit | Type of variable and response categories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identification of variables | ||||

| Identification code | M | M | M | Text |

| Date of visit | M | M | M | Date |

| Type of visit | M | M | M | Categorical (Initial visit/Follow-up visit/Reinitiation visit) |

| 2. Baseline and socio-demographic variables | ||||

| Date of inclusion in the cohort | M | Date | ||

| Date of birth | M | Date | ||

| Sex assigned at birth | M | Categorical (Male/Female) | ||

| Gender identity | M | Categorical (Man/Woman/Other) | ||

| Country of birth | M | Categorical | ||

| Level of education | M | Categorical (Incomplete primary education/Complete primary education/Complete compulsory secondary education or completed high school/University or higher education/Other) | ||

| Employment status | R | Categorical (Employee (working for others)/Self-employed/Internship contract/Unemployed/Student/Retired/Pre-retired/Household work/Incapacitated due to illness/Other) | ||

| Residence in a city participating in the programme | R | Categorical (Yes/No) | ||

| Residence in another autonomous community | R | Categorical (Yes/no) | ||

| Health resource from which the patient is referred to the programme* | R | Categorical (Primary Care/HIV/STI Center/Other healthcare facility/Community organization/By own decision/Other) | ||

| 3. Criteria for PrEP indication | ||||

| Target populationsa,* | M | Categorical | ||

| Risk practices for PrEP indication (last 12 months)* | M | Categorical (More than 10 sexual partners/Unprotected anal sex/Chemsex practice/Use of post-exposure prophylaxis/One or more bacterial STIs/Other) | ||

| 4. Use of PrEP prior to PrEP implementation | ||||

| Prior use of PrEP | R | R | Categorical (Yes/No) | |

| Source where PrEP was obtained | R | R | Categorical (Private clinic/Research study/Public PrEP program/Online purchase/Other) | |

| Drug used during the last PrEP cycle | R | R | Categorical (TDF-FTC/TAF/Other) | |

| Medical follow-up during the last PrEP cycle | R | R | Categorical (Yes/No) | |

| 5. Clinical variables: STIs | ||||

| Date of sample collection | M | M | M | Date |

| HIV test result | M | M | M | Categorical (Positive/Negative) |

| Diagnosis of gonococcal infection | M | M | M | Categorical (Yes/No) |

| Diagnosis of chlamydia infection | M | M | M | Categorical (Yes/No) |

| Site affected by gonococcal/chlamydia infection* | R | R | R | Categorical (Urethral/Urinary/Rectal/Pharyngeal) |

| Diagnosis of syphilis | M | M | M | Categorical (Yes/No) |

| Syphilis stage | M | M | M | Categorical (Primary/Secondary/Early latent/Late latent) |

| Hepatitis A status | M | M | M | Categorical (Acute/Past/Vaccinated/Non-immune) |

| Hepatitis B status | Categorical (Acute/Past/Vaccinated/Non-immune/Chronic) | |||

| Diagnosis of hepatitis C | M | M | M | Categorical (Yes/No) |

| Diagnosis of other STIs | R | R | Open text field | |

| Date of diagnosis of other STIs | R | R | Date | |

| 6. Clinical variables: renal function | ||||

| Date of sample collection | M | M | M | Date |

| Serum creatinine (dG/mL) | M | M | M | Numerical |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min) | M | M | M | Numerical |

| Urinalysis* | M | M | M | Categorical (Normal/Proteinuria/Glucosuria/Pyuria) |

| Albumin/creatinine ratio | R | R | R | Categorical (Normal/Abnormal) |

| 7. Behavioural variables (last 3 months) | ||||

| Frequency of condom use | R | R | R | Categorical (Never/Less than half/More than half/Always) |

| Drug use | R | R | R | Categorical (Yes/No) |

| Drug use per type* | R | R | R | Categorical (Poppers/cathinones/cannabis/GHB or GBL/ecstasy or MDMA/methamphetamine/speed/ketamine/heroin/others) |

| Chemsex | R | R | R | Categorical (Yes/No) |

| Injectable drugs | R | R | R | Categorical (Yes/No) |

| 8. PrEP monitoring | ||||

| Adverse effects* | M | Categorical (Nausea/Other Gastrointestinal symptoms/Other) | ||

| PrEP interruption | M | Categorical (Yes/No) | ||

| Consecutive PrEP dispensing date | M | Date | ||

| 9. Adherence to PrEP | ||||

| Correct PrEP dosing frequency | M | Categorical (Never/Occasionally/Regularly/Always) | ||

| Regime | R | Categorical (Daily/On demand/Both) | ||

| Number of days not taking PrEP | R | Numerical | ||

| Frequency of PrEP use in condomless sex | R | Categorical (Never/Occasionally/Regularly/Always) | ||

| 10. PrEP interruption | ||||

| Reason for interruption* | M | M | Categorical (Pregnancy/Renal function alteration/Other side effects/Lack of risk perception/Transfer/Other) | |

| Date took PrEP last | M | M | Date | |

| End of monitoring | M | M | Categorical (Yes/No) | |

| 11. Restarting PrEP | ||||

| Prescription date for resumption of PrEP | M | Date | ||

| Reason for reinstatement* | R | Categorical (Multiple sexual partners/Unprotected anal sex/Chemsex practice/Post-exposure prophylaxis use/One or more bacterial STIs/Other) | ||

M: mandatory; R: recommended; PrEP: HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

For all categorical variables, whenever “Other” option is selected, completing an open text field is suggested.

The project is managed through a website that healthcare professionals can access with an individual username and password (https://siprep.isciii.es). SIPrEP has been registered as a Computer Program in the Territorial Registry of Intellectual Property of the Community of Madrid, with reference number 16/2023/3520. The platform displays the corresponding questionnaires according to the type of visit. Data entry is conducted by healthcare professionals. PrEP centres or public health coordinators of the Autonomous Regions can share their PrEP data through an automatic upload tool that guarantees the consistency and coherence of the uploaded information.

Levels of access to data and legal and ethical considerationsThe permissions and user rights to register and consult data correspond to three organisational levels: centres participating in SIPrEP (whose professionals can register and access data from their centre), public health coordinators at the regional level (whose professionals can access data from all the centres in their Autonomous Region), and at national level (Division of HIV, STI, Viral Hepatitis and Tuberculosis Control and National Epidemiology Centre, whose professionals can access data from all the centres nation-wide).

The project was approved by the Ethical Committee for Research with Medicines of the Hospital Universitario la Princesa de Madrid (no. ISC-TEN-2020-01). All participants must sign an informed consent. The processing of personal data is registered with the Data Protection Office of the Carlos III Institute of Health in Madrid. All professionals participating in SIPrEP must sign a confidentiality agreement in which they undertake to comply with the stipulations of the General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 and Organic Law 3/2018. The rules established by these laws and the security mechanisms for protecting data used in the project are set out in the Security Document. Likewise, the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products has classified the study using Code No. ISC-TEN-2020-01.

Data quality control and statistical analysisThe web platform has filters to ensure data consistency and internal quality processes to detect errors. For these analyses, baseline characteristics (at the initial visit) were described. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies. Numeric variables are expressed as mean, standard deviation, and median with interquartile range. The cumulative incidence of HIV seroconversion at 54 months, its 95% confidence interval (CI), and the percentage of PrEP interruption and reinitiation were also calculated.

Scientific dissemination of PrEP informationA strategy has been designed to disseminate PrEP data through the public section of the web platform https://siprep.isciii.es, aimed at health professionals and potential PrEP users, and through Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube (@siprepred) aimed at health professionals and social actors in HIV. SIPrEP data analysis results are published on the website. A public directory of centres offering PrEP in Spain is displayed, including location, access details, and contact information. The website offers infographics, occasional videos, and links to other PrEP projects and resources. It also includes a programme to track visits globally and by page using Google Analytics.

ResultsAs of May 2024, 4159 people had been recruited into SIPrEP (14% of the total estimate of PrEP users in Spain, 28,798, following aggregated notification made by regional HIV coordinators to the Ministry of Health). Participants were mainly male (99%), mostly GBMSM (96%), with a median age of 36 years (interquartile range 30–43). The youngest PrEP user was 17 years old. Seven percent were under 25 years old. The majority were born in Spain (74%), 36% had a university education and were mainly employed (44%) or self-employed (6%). Thirty-eight percent of participants reported self-referral to PrEP centres, with 19% being referred from HIV/STI centres and 20% from primary care (Table 2). Ninety percent of participants stated that this was their first time using PrEP.

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics and referral to PrEP program.

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Total | 100 (4159) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 99.0% (4117) |

| Women | 1.0% (42) |

| Gender identity* | |

| Man | 96.7% (4022) |

| Woman | 2.4% (93) |

| Other | 0.9% (36) |

| Unknown | 0.2% (8) |

| Target population** | |

| GBMSM | 96.3% (4005) |

| Transgender women | 1.4% (57) |

| Female sex workers | 0.7% (28) |

| Male sex workers | 0.4% (16) |

| Cisgender women | 0.2% (9) |

| Cisgender men | 0.2% (8) |

| Unknown | 0.9% (36) |

| Age | |

| <25 years | 7.1% (297) |

| 25–34 years | 35.6% (1479) |

| 35–44 years | 35.1% (1459) |

| ≥45 years | 22.2% (924) |

| Region of birth | |

| Spain | 73.9 (3075) |

| Latin America | 18.5 (771) |

| Western Europe | 4.4 (184) |

| Central and Eastern Europe | 1.7 (72) |

| Other | 1.2 (48) |

| Unknown | 0.2 (9) |

| Level of education | |

| No studies | 0.3 (13) |

| Primary or secondary (compulsory) | 11.3 (471) |

| Baccalaureate (not compulsory) | 22.8 (946) |

| University/postgraduate | 36.1 (1503) |

| Other | 0.3 (13) |

| Unknown | 29.2 (1212) |

| Employment statusa | |

| Salaried | 43.7 (1818) |

| Self-employed | 6.1 (252) |

| Unemployed | 5.7 (237) |

| Other | 4.2 (174) |

| Unknown | 40.4 (1678) |

| Referral to PrEPa,* | |

| Primary Care Centre | 19.7 (820) |

| HIV/STI Centre | 19.4 (805) |

| Another healthcare setting | 8.3 (345) |

| Community organization | 5.6 (235) |

| Own decisión | 38.3 (1590) |

| Other | 4.0 (165) |

| Unknwon | 13.2 (548) |

GBMSM: gay, bisexual or another men who have sex with men; PrEP: HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

The most frequent criteria for PrEP indication (in the last 12 months) were having had more than ten sexual partners (84%), anal sex without a condom (78%), and at least one diagnosed STI (42%); 22% of participants had engaged in chemsex in the preceding year (Table 3). At baseline, 45% of participants had more than two of these risk practices, while 19% had only one.

Baseline behavioural practices of the SIPrEP cohort.

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Number of risk practices for PrEP indication (last 12 months) | |

| 1 | 18.5 (768) |

| 2 | 35.9 (1494) |

| 3 | 30.7 (1275) |

| 4 | 12.3 (511) |

| 5 | 1.8 (74) |

| Unknown | 0.9 (36) |

| Risk practices for PrEP indication (last 12 months)* | |

| More than ten sexual partners | 83.7 (3480) |

| Anal sex without a condom | 78.0 (3246) |

| Chemsex | 22.2 (924) |

| Use of PEP | 11.2 (468) |

| At least 1 STI diagnosed (previous year) | 42.2 (1757) |

| Other | 3.0 (126) |

| Use of drugs (last 3 months) | |

| Yes | 22.0 (913) |

| No | 34.8 (1447) |

| Unknown | 43.2 (1799) |

| Number of drugs used (last 3 months)a,b | |

| 1 | 44.1 (403) |

| 2 | 23.4 (214) |

| 3 | 14.4 (131) |

| Four or more | 12.8 (117) |

| Unknown | 5.3 (48) |

| Drugs used (last 3 months)a,b,* | |

| Poppers | 55.2 (504) |

| Cathinone | 27.5 (251) |

| Cocaine | 25.5 (233) |

| Cannabis | 23.1 (211) |

| GHB/GBL | 20.8 (190) |

| Ecstasy/MDMA | 13.7 (125) |

| Methamphetamine | 9.0 (82) |

| Speed | 6.8 (62) |

| Ketamine | 3.8 (35) |

| LSD | 1.2 (11) |

| Heroin | 0.02 (2) |

| Other | 5.3 (48) |

PrEP: HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis; PEP: HIV post-exposure prophylaxis; STI: sexually transmitted infection; GBH/GBL: gamma hydroxybutyrate/gamma butyrolactone; MDMA: 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine; LSD: lysergic acid diethylamide.

A total of 913 participants (22%) reported drug use three months before entering SIPrEP; 55% used poppers, 28% cathinones, 26% cocaine, 23% cannabis, 21% GHB/GBL, and 9% methamphetamine (Table 3). At baseline, 21% (814) were diagnosed with at least one of these STIs; 8% (348) with syphilis, 7% (300) with gonococcal infection, and 7% (270) with chlamydia infection. The most frequent locations for gonococcal and Chlamydia trachomatis infection were rectal (55% (n=164) and 70% (n=188) of participants, respectively); 35% (122/348) of syphilis diagnoses were primary stage. Additionally, 11 participants were diagnosed with hepatitis A (0.3%), 4 with hepatitis B (0.1%), and 13 with hepatitis C (0.3%) at the initial visit (Table 4).

Baseline clinical characteristics of PrEP users.

| Sexually transmitted infection | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Total syphilis cases | 8.4 (348) |

| Primary syphilis | 35.1 (122) |

| Secondary syphilis | 15.2 (53) |

| Early latent syphilis | 14.1 (49) |

| Latent syphilis of unknown duration | 27.9 (97) |

| Unknown stage | 7.8 (27) |

| Gonococcal infection (total cases) | 7.2 (300) |

| By site of infection | |

| Urethral | 19.7 (59) |

| Rectal | 54.7 (164) |

| Pharyngeal | 46.0 (138) |

| Unknown | 0.3 (1) |

| Chlamydia trachomatis infection*(total cases) | 6.5 (270) |

| By site of infection | |

| Urethral | 23.3 (63) |

| Rectal | 69.6 (188) |

| Pharynx | 14.1 (38) |

| Unknown | 1.5 (4) |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | 0.4 (16) |

| Hepatitis A status | |

| Immunea | 50.2 (2,089) |

| Susceptible | 34.5 (1,434) |

| Unknown | 15.3 (636) |

| Hepatitis B status | |

| Immunea | 63.6 (2,647) |

| Susceptible | 26.2 (1,089) |

| Chronic infectionb | 0.3 (14) |

| Unknown | 9.8 (409) |

| Diagnosis of hepatitis C | |

| Incident case | 0.3 (13) |

| Negative | 94.1 (3,913) |

| Unknown | 5.6 (233) |

Among those with follow-up visits registered, the average number of visits per participant throughout the study period was 3.6 (SD=2.9). Overall, PrEP discontinuation was reported in 15% (642), of whom around 34% (216) eventually returned to the clinic to resume PrEP. The most common reason for stopping PrEP was a lack of perceived risk (35%; 224). Seven percent (44) stopped due to entering a stable relationship, and 7% (45) for other unspecified personal reasons. Twenty-one percent (133) stopped for relocation reasons, although it is still being determined how many resumed PrEP at their new destination. Two percent (14) discontinued due to COVID-19 or Mpox. In 56 (9%) of discontinuations, impaired renal function was the cause, and in 61 (10%) cases, other adverse effects. These categories are not mutually exclusive. Finally, 15% of withdrawals (94) were considered a loss to follow-up, and the reason could not be recorded.

Four HIV seroconversions were identified in the study period, corresponding to an incidence 0.12/100 person-years of 0.12/100 person-years (95% CI 0.05–0.33). These included three GBMSM and one transgender woman, with a median age of 30 years. In three cases, HIV diagnosis was made at the second PrEP visit, within the first 12 weeks of starting PrEP. For the transgender woman, HIV was diagnosed at the sixth visit (1.5 years after restarting PrEP, as she had stopped for six months), and adherence was also reported as suboptimal. None of them had used PrEP previously.

From 1st September 2020, the website received 70,833 visits and 46,754 unique visits. The most visited page (31,210 views) was the public directory of PrEP centres in Spain. On social media, there were 411 posts on X (formerly Twitter), 137 on Instagram (with 1027 interactions), 173 on Facebook, and 34 YouTube videos (with 6454 views).

DiscussionWe report on implementing the information system, SIPrEP, to monitor PrEP use in real-life conditions in Spain. The data collected allows us to describe the characteristics of people taking PrEP, which is of considerable value and provides policymakers with data to optimize interventions. In May 2024, SIPrEP provides the characteristics of 14% of them, with total population coverage having increased by 4% in the last two year.14

The characteristics of PrEP users studied are as expected and align with other national and international publications.11,19,20 The majority are GBMSM, in their 30s, and highly educated. This population is at high risk of HIV infection, as evidenced by their high number of sexual partners, chemsex, inconsistent condom use, and high frequency of STIs at baseline. PrEP programmes in Spain reach the highest HIV incidence group. However, the number of transgender people, cis-heterosexual women, and female sex workers is low, which requires further thoughts. Likewise, the proportion of migrants is also strikingly low compared to their high representation in new HIV diagnoses in Spain. These findings highlight the need to analyze the barriers to access that these more vulnerable groups may be experiencing in relation to PrEP programs. Given these data cover 14% of PrEP users, it's not possible to assess whether characteristics vary across the country, especially without data from the largest cities.

The average number of visits per participant was low. Given that SIPrEP is an open cohort, this may partly reflect that participants initiated PrEP at different points in time, some of them recently. However, other factors may also contribute to this finding. Clinical follow-up visits may be scheduled less frequently than recommended due to workload constraints in healthcare settings, and some visits may not be consistently recorded in the SIPrEP system. As a result, our ability to fully assess patterns of long-term engagement in care, discontinuation, and reinitiation of PrEP is limited.

The observed proportion of people reporting PrEP discontinuation was 15%. However, this figure should be interpreted with caution. It may be underestimated due to the limitations described above, particularly the under-registration of follow-up visits and the possibility of losses to follow-up not being captured as discontinuation. In addition, the voluntary participation of sites in SIPrEP may have led to the inclusion of more motivated professionals, potentially resulting in better-than-average retention. Together, these factors suggest that the true rate of discontinuation could be higher than what our data reflect.

Regarding the reasons for discontinuation, loss of risk perception was the most frequently reported factor, aligning with previous findings from other countries. Several studies have documented that individuals often discontinue PrEP due to changes in their sexual behavior, such as entering a stable relationship or reducing the number of sexual partners.21–24 For instance, Whitfield et al.21 reported that 50% of participants discontinued PrEP for these reasons, while studies in France and Germany found similar trends, with 32%22 and 49.1%23 of participants, respectively, citing a reduced need for PrEP as their main reason for stopping. A systematic review further supports this pattern, highlighting that perceived risk is a key factor in PrEP discontinuation and reinitiation.25

Discontinuation due to adverse effects was less common but remains a relevant concern. Reports indicate that the proportion of participants stopping PrEP due to side effects varies, ranging from 2.9%26 to 17.5%.23 In our cohort, costs associated with PrEP uptake and difficulties navigating the healthcare system were not frequently reported as reasons for discontinuation,27,28 though this aspect should be further explored to ensure appropriate support for users experiencing tolerability issues.

We found four seroconversions. Given the short time between PrEP start and three of these, these are likely undiagnosed infections during the window period as all had, by protocol, and HIV-negative test at baseline. Studies like PrEP Impact assume infections occurring up to week 6 are pre-existing.17 The fourth seroconversion occurred in a person who stopped PrEP for a long period. Studies such as the Kaiser Permanente Northern California cohort show higher infection rates in individuals with gaps in the PrEP continuum, mainly among those who discontinued and did not reinitiate.29

The HIV seroconversion incidence over 54 months was low (0.12/100 person-years). Other cohort studies report similarly low incidence: AMPrEP (0.3/100)30; the French National Health Study found (0.19/100)31; and a US national cohort (0.8/100).32

Other countries have initiated PrEP cohort studies, such as the one in Ile-de-France, France.33 Different approaches involve retrieving data from existing GBMSM cohorts, e.g. in the United States of America34 and in Lisbon, Portugal.35 Scotland has implemented monitoring systems that provide macro-indicators of PrEP uptake.36 SIPrEP is an example of a dynamic, prospective cohort system that allows in-depth monitoring of a nationwide public health strategy, providing clinical and behavioural data for future research.

Visits to the SIPrEP website were high. Similar results were reported by the US PrEP locator,37 the only other online PrEP directory that has published data. Awareness of PrEP among GBMSM is limited in Spain,37 the only other online PrEP directory that, to our knowledge, has published data on its metrics. Our results are relevant since awareness among GBMSM has shown to be limited in Spain.38,39

One strength of SIPrEP is its collaborative nature, involving all actors related to PrEP in Spain. Due to Spain's political and territorial structure, where Autonomous Regions manage healthcare and public health, SIPrEP's design and implementation experience may be useful in similar scenarios.

Nineteen percent of PrEP users meet only one of the two mandatory eligibility criteria outlined in national guidelines, suggesting some practitioners prescribe PrEP based on broader criteria. Some authors recommend that PrEP Guidelines be expanded beyond risk practices.40

This work has limitations. SIPrEP, launched in July 2020, faced delays due to COVID-19, impeding implementation. Only 14% of PrEP users in Spain are included, and scale-up is ongoing. This 14% may not fully represent PrEP users in Spain, as data from major cities like Barcelona and Madrid are absent. Delays are caused by regional organizational challenges, not refusals from PrEP users. Despite this, we do not expect major differences in PrEP users across Spain, though this bias may explain the under-representation of transgender people in early analyses. The lack of a standardized definition for chemsex in this cohort, along with the fact that slamming was not included as a practice, are limitations of this study. This highlights the need for future evaluations to adopt uniform definitions for chemsex and ensure that all relevant practices are captured to better understand its impact.

SIPrEP has proven valuable for PrEP monitoring and providing real-time strategic information for decision-making. It confirms that PrEP programmes are reaching the target population but highlights the low number of transgender users, requiring further action.

Ethical approval and consent to participateThe Ethics Committee approved this study for Research with Medicines of the Hospital Universitario la Princesa de Madrid (registration number ISC-TEN-2020-01).

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT for translation and proofreading of specific sections of the text. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

FundingThe project has been carried out thanks to non-competitive public funding from the Division for the Control of HIV, STIs, Viral Hepatitis and Tuberculosis (DCVIHT). The project has also benefited from cooperation with the HIV Surveillance Unit, the AIDS Research Network (RIS), and CIBERINFEC, which provided human resources. We gratefully acknowledge the agreement between the Ministry of Health and the Spanish Interdisciplinary AIDS Society (SEISIDA).

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicting interests.

We want to thank the regional HIV coordinators and all the healthcare professionals in the centres with PrEP programmes who have contributed and continue to contribute to the design and implementation of SIPrEP. We acknowledge the hospitals that participated in the pilot study: Hospital Universitario de Donostia, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Hospital Marina Baixa, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Centro de Salud Internacional y Enfermedades Transmisibles de Drassanes, and BCN Checkpoint.