New tools are needed for early evaluation of patients who could be infected by COVID-19 during this pandemic. M-Health (apps) could be a solution in this setting to evaluate a COVID-19 diagnosis. The aim of this study was to describe which COVID-19s apps are available in Spain.

MethodsWe made a review of the diagnosis apps and websites of the different regions of Spain. We described the different characteristics of each app.

ResultsWe analyzed 6 apps, 5 corresponding to Autonomous Communities and one from the Ministry of Health, as well as 4 website test from the respectively health region. There were detected multiples differences between the m-Health methods analysed from the information collected to the information shared to citizens. However, all m-Health methods asked about the classic triad symptoms: fever, cough and dyspnoea.

ConclusionAlthough the COVID-19 Spanish crisis have been lead from the Ministry of Health, it has been detected different methods to apply m-Health though the multiple Spanish regions.

Ante la pandemia por la COVID-19 son necesarias nuevas herramientas de trabajo a nivel sanitario para la evaluación precoz de las personas sospechosas de haber sido infectadas. La tecnología de la información y comunicación (TIC) puede dar solución a este nuevo escenario. El objetivo de este estudio es conocer qué TIC hay en España.

MétodosRevisión de la TIC (aplicaciones móviles y páginas web) de las comunidades autónomas de España, listando las características recogidas de cada una de ellas.

ResultadosSe han analizado seis aplicaciones móviles correspondientes a cinco comunidades autónomas y una del Ministerio de Sanidad, además de cuatro test en páginas web de la Consejería de Salud de la comunidad autónoma correspondiente. De las TIC observadas, existen muchas diferencias entre ellas, tanto en la información recogida como en los recursos dedicados al ciudadano. Si bien todas ellas preguntan por la tríada clásica de síntomas COVID-19: fiebre, tos y disnea.

ConclusionesA pesar de tener un órgano organizador común en la crisis de la COVID-19 en España, el Ministerio de Sanidad, se han observado diferentes métodos de aplicación en la tecnología de la información y comunicación en los territorios autonómicos de España.

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) has been proposed as an aid to managing the crisis1. m-Health (mobile health) is very widespread, and in an emergency health situation it has been proposed as a useful tool that enables self-diagnosis and follow-up of patients with suspected COVID-19.

The use of ICT in COVID-19 originated in China. There, a mobile app was launched that provided information on people’s location in the two weeks prior to contact with people with COVID-192. This model has been implemented in other countries, such as South Korea, and in Europe and America3,4.

The objective of this study has been to conduct a review of the various ICT solutions, apps and web pages intended to manage and/or give a presumptive diagnosis of COVID-19 in Spain.

MethodsEach region’s ICT solution was located by performing a search of the different websites of the Health Ministries of the Autonomous Regions of Spain. The ICT solutions were studied using volunteers from each autonomous region, although no representation was available for Castile-La Mancha, La Rioja and Navarre. The volunteers received express information on the study’s objective, and their verbal consent to participate was obtained. The ICT solution was used by the volunteer, entering their personal data, accompanied remotely or in person by one of the co-authors who collected the characteristics.

A review was made of all the ICT solutions (apps and web pages) available to date in the different autonomous regions (ARs) and that of the national Ministry of Health (which serves the Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile-La Mancha, Extremadura and the Principality of Asturias) intended to carry out follow-up or presumptive diagnosis of COVID-19 based on a questionnaire. The Aragon app uses Andalusia’s algorithm, but the two apps are considered separately in spite of this similarity.

The assessment questionnaire was structured with items relevant to the assessment of a person with suspected COVID-19. Following the recommendations of the Ministry of Health and its app, the following information was collected: sociodemographic characteristics, personal medical history, epidemiological description, possible COVID-19 symptoms, performance of diagnosis and follow-up.

The review analysed and compared the data requested by these digital resources.

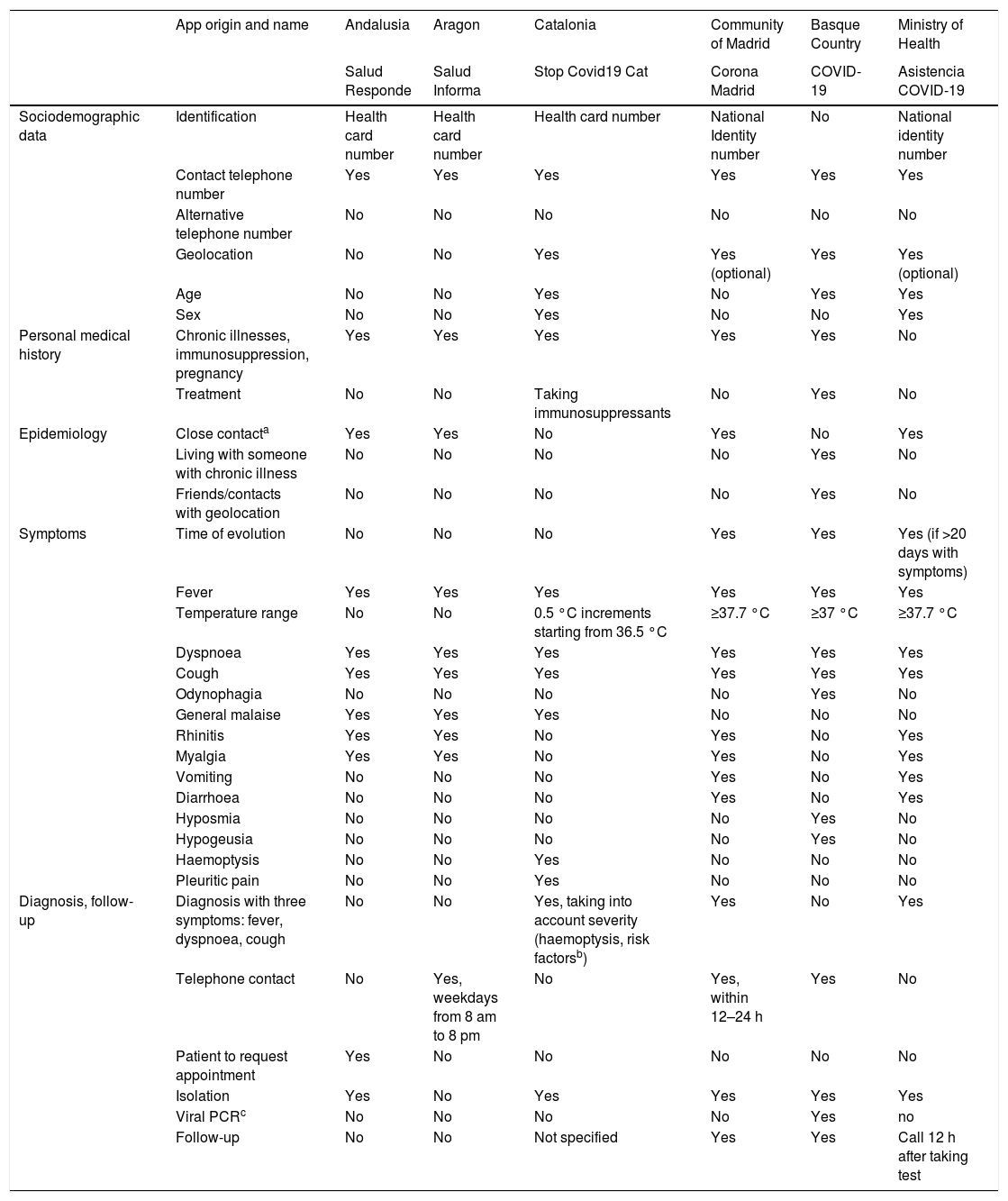

ResultsOf the 17 ARs, information to assess COVID-19 could be accessed via an app in five: Andalusia, Aragon, Catalonia, the Community of Madrid (CMad) and the Basque Country (BC). Sociodemographic data were collected specifically in Catalonia, and could be obtained in the other apps through health card details. Geolocation was requested in Catalonia, CMad and BC. Medical history and conditions of vulnerability were considered in all of them. With regard to symptoms assessed, all asked about the triad of cough, fever and dyspnoea. Diagnosis of suspected COVID-19 infection can be seen in the Catalonia and CMad apps. Telephone contact by the healthcare service is described in the CMad app, while in Aragon and BC the option to contact healthcare services is given. Diagnosis of suspected COVID-19 was only found in the Catalonia and CMad apps, and active telephone follow-up in the BC app, with the majority recommending self-isolation and providing a telephone number to activate the corresponding healthcare service. The Ministry of Health app was found to be complete in terms of content, diagnosis and follow-up. The apps consulted are compliant with the law on data protection. The collection of data by the apps is summarised in Table 1.

Data collected in the mobile apps of the autonomous regions.

| App origin and name | Andalusia | Aragon | Catalonia | Community of Madrid | Basque Country | Ministry of Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salud Responde | Salud Informa | Stop Covid19 Cat | Corona Madrid | COVID-19 | Asistencia COVID-19 | ||

| Sociodemographic data | Identification | Health card number | Health card number | Health card number | National Identity number | No | National identity number |

| Contact telephone number | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Alternative telephone number | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Geolocation | No | No | Yes | Yes (optional) | Yes | Yes (optional) | |

| Age | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Sex | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Personal medical history | Chronic illnesses, immunosuppression, pregnancy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Treatment | No | No | Taking immunosuppressants | No | Yes | No | |

| Epidemiology | Close contacta | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Living with someone with chronic illness | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Friends/contacts with geolocation | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Symptoms | Time of evolution | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes (if >20 days with symptoms) |

| Fever | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Temperature range | No | No | 0.5 °C increments starting from 36.5 °C | ≥37.7 °C | ≥37 °C | ≥37.7 °C | |

| Dyspnoea | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Cough | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Odynophagia | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| General malaise | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Rhinitis | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Myalgia | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Vomiting | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Diarrhoea | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Hyposmia | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Hypogeusia | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Haemoptysis | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Pleuritic pain | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Diagnosis, follow-up | Diagnosis with three symptoms: fever, dyspnoea, cough | No | No | Yes, taking into account severity (haemoptysis, risk factorsb) | Yes | No | Yes |

| Telephone contact | No | Yes, weekdays from 8 am to 8 pm | No | Yes, within 12–24 h | Yes | No | |

| Patient to request appointment | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Isolation | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Viral PCRc | No | No | No | No | Yes | no | |

| Follow-up | No | No | Not specified | Yes | Yes | Call 12 h after taking test |

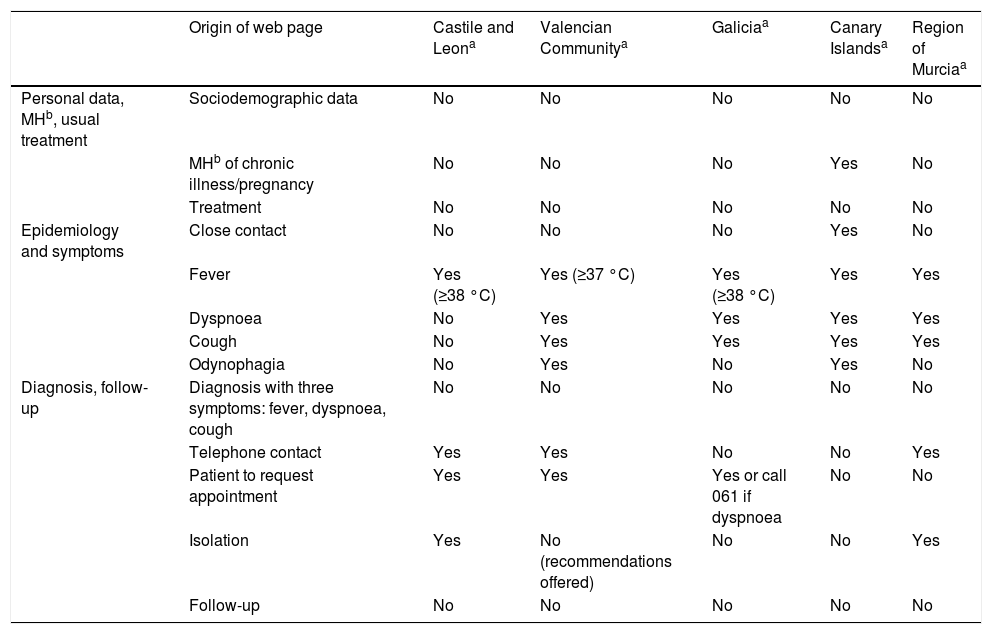

In contrast, the option to get a test online is available in Castile and Leon, the Valencian Community, Galicia, the Canary Islands and the Region of Murcia. The algorithms used are simpler than those in the apps, since they do not collect sociodemographic data, telephone number or suspected coronavirus diagnosis. The results are summarised in Table 2.

Data collected from the web pages of the autonomous regions that lack a mobile app.

| Origin of web page | Castile and Leona | Valencian Communitya | Galiciaa | Canary Islandsa | Region of Murciaa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal data, MHb, usual treatment | Sociodemographic data | No | No | No | No | No |

| MHb of chronic illness/pregnancy | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Treatment | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Epidemiology and symptoms | Close contact | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Fever | Yes (≥38 °C) | Yes (≥37 °C) | Yes (≥38 °C) | Yes | Yes | |

| Dyspnoea | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Cough | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Odynophagia | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Diagnosis, follow-up | Diagnosis with three symptoms: fever, dyspnoea, cough | No | No | No | No | No |

| Telephone contact | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Patient to request appointment | Yes | Yes | Yes or call 061 if dyspnoea | No | No | |

| Isolation | Yes | No (recommendations offered) | No | No | Yes | |

| Follow-up | No | No | No | No | No |

Web pages: Castile and Leon (https://www.saludcastillayleon.es/sanidad/cm/gallery/COVID19/autotriaje.html), Valencian Community (http://coronavirusautotest.san.gva.es/autotest_es.html), Galicia (https://coronavirus.sergas.gal/autotest/index.html?lang=gl-ES), Canary Islands (https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/sanidad/scs/COVID-Test/), Region of Murcia (https://sms.carm.es/CoronavirusAutoTest.html).

The ARs for which app content to assess COVID-19 was not available were Castile-La Mancha, La Rioja and Navarre. The autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla and the regions of Cantabria, Extremadura, the Balearic Islands and the Principality of Asturias have neither web pages nor apps5–10.

DiscussionInformation on COVID-19-related ICT was obtained from six apps and four AR websites. The most complete apps were those of Catalonia, CMad, BC and the Ministry of Health. The evaluations of web pages were poor in terms of COVID-19 assessment.

Neither the World Health Organization (WHO) nor the European Union has issued a statement on app- or web-based COVID-19 diagnosis. In Spain, we have seen the appearance of such tools associated with the health card. The degree of availability of ICT solutions can present a limitation in their access for those who do not have a health card from the corresponding community. None of the apps has been validated or has a certificate from health app quality agencies11. The technical quality of such devices is essential, and certification provides a guarantee that ICT solutions meet certain minimum quality and security standards.

With regard to the advice given to citizens about their likelihood of having COVID-19 in the presence of certain symptoms, two tendencies were observed: consideration of the classic triad (fever, cough, dyspnoea) and expansion to other symptoms considered by the WHO (asthenia, expectoration, odynophagia, headache, myalgia, chills, nausea or vomiting, nasal congestion, diarrhoea or haemoptysis)12. Each region takes a different approach to these symptoms. Variability was found between the questions asked, except in relation to the classic triad, although even there, there was no unanimity with regard to values such as temperature at which to suspect infection. Over the course of the pandemic, myalgia, headache, hyposmia, hypogeusia and digestive alterations have been suggestive of COVID-1913. Moreover, time of evolution should be considered a key question when screening for severity. The variability of the questions recorded by the multitude of ICT solutions consulted makes the diagnosis of patients without the typical symptoms difficult, as well as the identification of warning symptoms, except in the Catalonia app. The limited number of COVID-19 symptoms considered may have led to underdiagnosis in the early stages of the pandemic.

There is a large degree of heterogeneity in the follow-up of users who complete the ICT solutions’ questionnaires. In some ARs, an assessment and follow-up by healthcare professionals is offered, but neither the service nor who is responsible for it are specified. One of the main weaknesses is that the decision-making algorithm is not transparent, which we feel should be publicly available to healthcare professionals. In turn, the apps and web pages could be used by health centres to divert calls to healthcare professionals, guaranteeing follow-up based on severity, the potential for which is not integrated in the usual healthcare pathway.

Furthermore, the ICT solutions analysed report, but do not record the forms of, contact with other cases being followed due to suspected COVID-19. Contact tracing is hugely important in pandemics, but it has not been possible to carry it out, which may be due to compliance with the law on data protection. The use of ICT to facilitate contact tracing should be considered, reassessing the benefit of collecting this information.

If the ICT solutions make referrals to health services where necessary, without depending solely and exclusively on citizen proactivity, they could be a tool with potential for population screening and mapping. The coexistence of multiple ICT solutions, with access limited to the citizens of each autonomous region, means that access to resources is unequal, both due to the health card of the corresponding autonomous region being required and due to the different items assessed in each region. We are of the view that a single app with registration using the national identity number (DNI)/foreign resident identification number (NIE) would be more accessible to the population as a whole.

Finally, the potential of these tools in terms of their capacity to detect possible cases, follow-up of the same, study of contacts and, above all, prevention of complications through early diagnosis is evident, but they require validation in order to bring them into general use, with a guarantee of follow-up by healthcare professionals with access to the patient’s medical record.

This study has certain limitations to consider. On the one hand, it was not possible to evaluate all of the ICT solutions of the 17 ARs in Spain. On the other hand, the ICT solutions have not been re-evaluated since the start of the crisis, at the end of March, and changes may have been made to them as the pandemic unfolded.

ConclusionsThe lack of consensus among the different regions has led to extensive heterogeneity in the items used for COVID-19 assessment by the ICT solutions. The potential of ICT solutions as a diagnostic tool needs to be evaluated carefully by the competent bodies in order to unify the criteria.

Author contributionsSara Ares-Blanco wrote the first draft of the article, which was completed by Lubna Dani Ben Abdellah and Marina Guisado-Clavero. The tables were designed and filled in by Sara Ares-Blanco and Marina Guisado-Clavero. All three authors contributed to the discussion and conclusion sections. All three authors approved the final version of the manuscript and collaborated in the same way in the preparation of the article.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Thanks to Clara Maestre and Mada Muñoz (nurses at the Institut Català de la Salut [Catalan Institute of Health], Barcelona), for contributing to the collection of data from the apps, as well as to Isa Díaz, Loida Ruiz and Gerson Mariño.

Please cite this article as: Guisado-Clavero M, Ares-Blanco S, Ben Abdellah LD. Uso de aplicaciones móviles y páginas web para el diagnóstico de la COVID-19 en España. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:454–457.