The VINCat Program: a 19-year model of success in infection prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections in Catalonia, Spain

More infoThis study aimed to describe the epidemiological trends of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), and Clostridioides difficile in Catalonia, Spain.

MethodsWe analyzed data from hospitals participating in the VINCat Program from 2008 to 2022. The study analyzed antimicrobial susceptibility data from isolates collected in acute care hospital settings. Key metrics: annual MRSA rate, incidence density of new MRSA cases, MRSA bacteremia, and hospital-acquired MRSA cases. We assessed the rate of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae and carbapenemase-resistant (CR)-K. pneumoniae, CR-Enterobacter cloacae, and CR-Escherichia coli. For C. difficile infections (CDI), the incidence density was determined.

ResultsWhile MRSA rate slightly decreased over the study period, the incidence of MRSA bacteremia increased. Global hospital-acquired MRSA incidence decreased but increased in small hospitals. Among patients with bacteremia, the rate of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae remained stable; in contrast, the rate of CR-K. pneumoniae rose in large centers as well as did the rates of CR-E. cloacae and CR-E. coli. CDI incidence rose substantially over the study period.

ConclusionVINCat's hospital surveillance system has provided valuable insights into the evolving incidence of key multidrug-resistant organisms and CDI. These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions, particularly for MRSA in smaller hospitals and for CR-Enterobacteriaceae and CDI across all hospital sizes.

Describir las tendencias de los principales patógenos asociados a la atención sanitaria en Cataluña, España.

MétodosSe analizaron datos de hospitales participantes en el Programa VINCat. La población del estudio incluyó a pacientes tratados en áreas de agudos, y se basó en informes de susceptibilidad antimicrobiana. Indicadores: tasa anual de Staphylococcus aureus resistente a meticilina (SARM), densidad de incidencia de nuevos casos de SARM, de bacteriemia por SARM y de casos de SARM de adquisición hospitalaria.

Para Klebsiella pneumoniae productora de beta-lactamasa de espectro extendido (BLEE) y productoras de carbapenemasa (PC), Enterobacter cloacae y Escherichia coli PC: tasa de resistencia. Infecciones por Clostridioides difficile (ICD): densidad de incidencia.

ResultadosLa tasa de SARM disminuyó del 23,73% al 21,34%, mientras que la incidencia de bacteriemia por SARM aumentó de 0,68 a 0,74 casos por 10.000 días-paciente (2015-2018 vs. 2019-2022). El SARM adquirido en el hospital disminuyó en los hospitales grandes de 0,77 a 0,66 casos por 10.000 días-paciente, pero aumentó en los hospitales pequeños de 0,58 a 0,81 casos (2012-2017 vs. 2018-2022). En pacientes con bacteriemia, la tasa de K.pneumoniae-BLEE se mantuvo estable por encima del 22%; en cambio, la tasa de K.pneumoniae-PC aumentó en centros grandes del 2,82% al 4,45%, al igual que las tasas de E.cloacae-PC (1,22% frente al 3,21%) y E.coli (0,07% frente al 0,26%) (2014-2017 vs. 2018-2022). La incidencia de ICD aumentó de 2,8 casos por 10.000 días-paciente a 4,19 casos (2008-2012 vs. 2018-2022).

ConclusiónEl sistema de vigilancia de VINCat ha proporcionado información valiosa sobre la evolución de patógenos claves asociados a la atención sanitaria.

The rising prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) poses a significant public health challenge worldwide, contributing to increased healthcare costs and morbidity. The prevalence of these microorganisms varies considerably by bacterial species and geographical region.1,2 Among the most concerning MDROs are methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, and, more recently, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae – all of which are associated with limited treatment options, healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), and potential outbreaks.3 The European Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance System (EARSS) provides critical insights into multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs).1 Between 2018 and 2022, the percentage of MRSA in invasive isolates decreased from 17.8% to 15.2%. However, significant geographic variations were noted, ranging from less than 1% in northern Europe to over 25% in southern and eastern regions. During the same period, the incidence of bloodstream infections caused by MRSA declined from 5.80 to 4.94 cases per 100,000 population. In 2022, the prevalence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in invasive isolates was 32.7%, with the highest rates observed in southern and eastern Europe (>25%), compared to northern Europe (>10%). Similarly, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae accounted for 10.9% of invasive isolates in 2022, following a geographic distribution pattern comparable to that of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae. In contrast, carbapenem-resistant isolates remained rare among invasive Escherichia coli isolates. Clostridioides difficile, the leading cause of healthcare-associated infectious diarrhea, has experienced a significant rise in incidence over the past decade. This increase is likely due to a growing number of at-risk patients and advances in diagnostic methods, including the identification of community-associated infections, particularly in developed countries.4–6

Effective surveillance is the cornerstone of infection prevention and control programs targeting MDROs and C. difficile.7 A robust hospital surveillance system is essential for establishing baseline infection rates, monitoring trends over time, and evaluating the effectiveness of implemented control measures. Moreover, such surveillance enables institutions to benchmark their performance against similar organizations, promoting continuous improvement in infection prevention and control efforts. The VINCat is a program of the Catalan Health Service created to establish a unified surveillance system for HAIs in Catalonia, Spain, which had a population of eight million in 2024. Its objective is to reduce the incidence of HAIs through continuous, active epidemiological monitoring. The program relies on the expertise of multidisciplinary infection control teams across healthcare centers and has been systematically collecting data since 2008.

This study aims to describe the trends in MRSA, ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and C. difficile infections (CDI) recorded in hospitals participating in the VINCat Program from 2008 to 2022.

MethodsStudy design and hospital participationThis longitudinal descriptive study was conducted over a 15-year period from 2008 to 2022. The study was conducted in acute care hospitals participating in the VINCat Program, all of which have an infection control team (ICT) and are structured based on hospital size. Hospitals were categorized into four groups: Group 1 (large) with over 500 beds, Group 2 (medium) with 200 to 500 beds, Group 3 (small) with fewer than 200 beds and Group 4, hospitals that did not fit into the size-based stratification and consisted of specialized centers (3 oncology centers and 1 urology center). All hospitals followed uniform surveillance protocols.

Data collectionThe study population of MRSA, ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae and E. coli) were based on antimicrobial susceptibility reports provided by the microbiology laboratory during each period and consisted of isolates from patients treated in any acute care area of the hospital (hospitalization units, outpatient clinics, emergencies, etc.), regardless of their age. Data only included unduplicated strains from samples obtained for clinical purposes, regardless of their clinical value (colonization or infection) and the location of acquisition. Samples from active surveillance of carriers were not included. Bacteremia due to ESBL K. pneumoniae, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae and E. coli was defined as any episode of clinically significant bacteremia (one episode per patient), regardless of the source of infection and where it was acquired.

The study population for CDI surveillance consisted of adult patients (≥18 years) diagnosed with CDI during the surveillance period. Cases of CDI were defined as patients with acute diarrhea or toxic megacolon without another known cause, plus one of the following: (1) stool sample with a toxin A- or B-positive laboratory result for C. difficile, or detection of genes that encode toxin by molecular testing; (2) endoscopic, surgical or histological examination confirming the diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis. Colonized and asymptomatic patients have not been included, even if they carry a toxin-producing strain. Patients with a previous history of CDI and those hospitalized in palliative care and convalescence units were excluded. CDI was classified according to the site of acquisition of diarrhea: (1) Hospital-acquired CDI: infection identified >48h after admission to the hospital and before discharge. (2) Non-nosocomial healthcare-related CDI: infection starting in the community or within 48h of admission, in patients admitted to a health center (hospital, nursing home or community healthcare center) in the 4 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms. (3) Community-acquired CDI: infection starting in the community or within 48h of admission, with no admission to a healthcare center in the last 4 weeks.

Surveillance metricsFor methicillin-resistant S. aureus:

- •

MRSA rate

- •

Incidence density of MRSA bacteremia

- •

Incidence density of new cases of MRSA

- •

Hospital-acquired MRSA cases

For ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae:

- •

Rate of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae:

- •

Rate of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae bacteremia:

For carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae:

- •

Rate of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, and E. coli.

- •

Rate of carbapenem-producing K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, and E. coli bacteremia.

For C. difficile:

- •

Incidence density of C. difficile infections

Detailed definitions of metrics calculation have been provided in supplementary material (metrics definition and calculation).

Statistical analysisThe data were summarized using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. We presented medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or means and standard deviations for continuous variables, depending on the distribution. Incidence rates were calculated by dividing the total number of cases by the total person-time at risk and adjusting for 10,000 patient-days, as appropriate. Analyses were stratified into relevant time periods. We conducted chi-square or Fisher's tests to assess differences in percentages, as deemed suitable. For continuous variables, comparisons were performed using t-Student or Wilcoxon tests, as appropriate. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated to quantify the magnitude and direction of these differences. We computed incidence rate ratios (IRR) to compare incidence rates. When comparing the two periods, we used the earlier period as the reference. In cases where three periods were compared, we evaluated the two most recent periods while taking the earliest of those two as the reference. To assess the degree of correlation and the direction of the relationship between incidence rates and years, we performed Spearman correlation (rho). LOESS smoothing was applied to the graphs to enhance the visualization of data trends. A significance level of 0.05 was applied to all statistical tests. Statistical tests were not explicitly adjusted for multiple comparisons. The results were analyzed using the R statistical software, version 4.2.2, developed by The R Foundation in Vienna, Austria.

Ethical aspectsHospital participation in the VINCat Program is voluntary. The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, with international human rights, and with the legislation regulating biomedicine and personal data protection. All data were treated as confidential, and records were accessed anonymously. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bellvitge Hospital (Ref. PR066/18). The Ethics Committee for Clinical Research waived the requirement for informed consent.

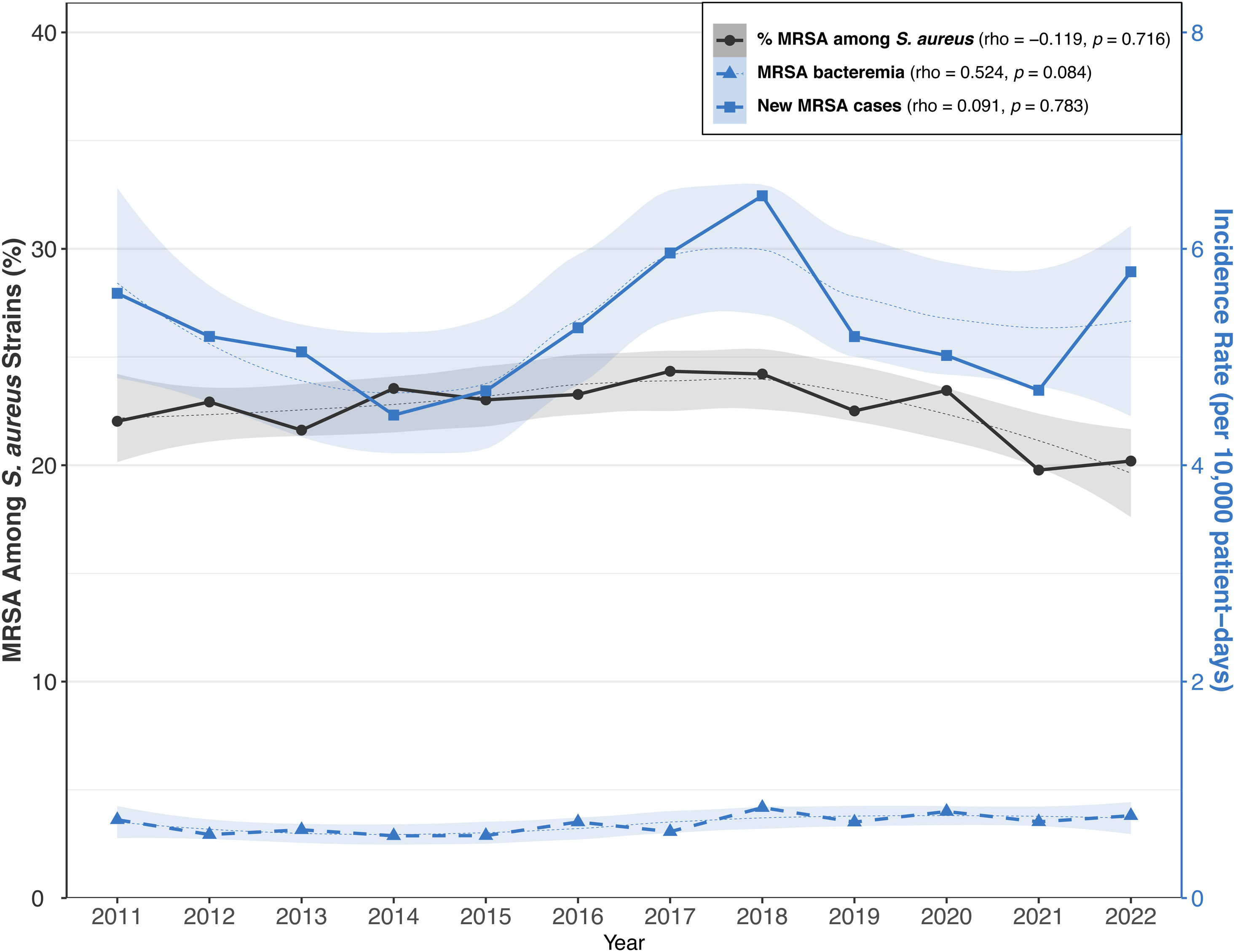

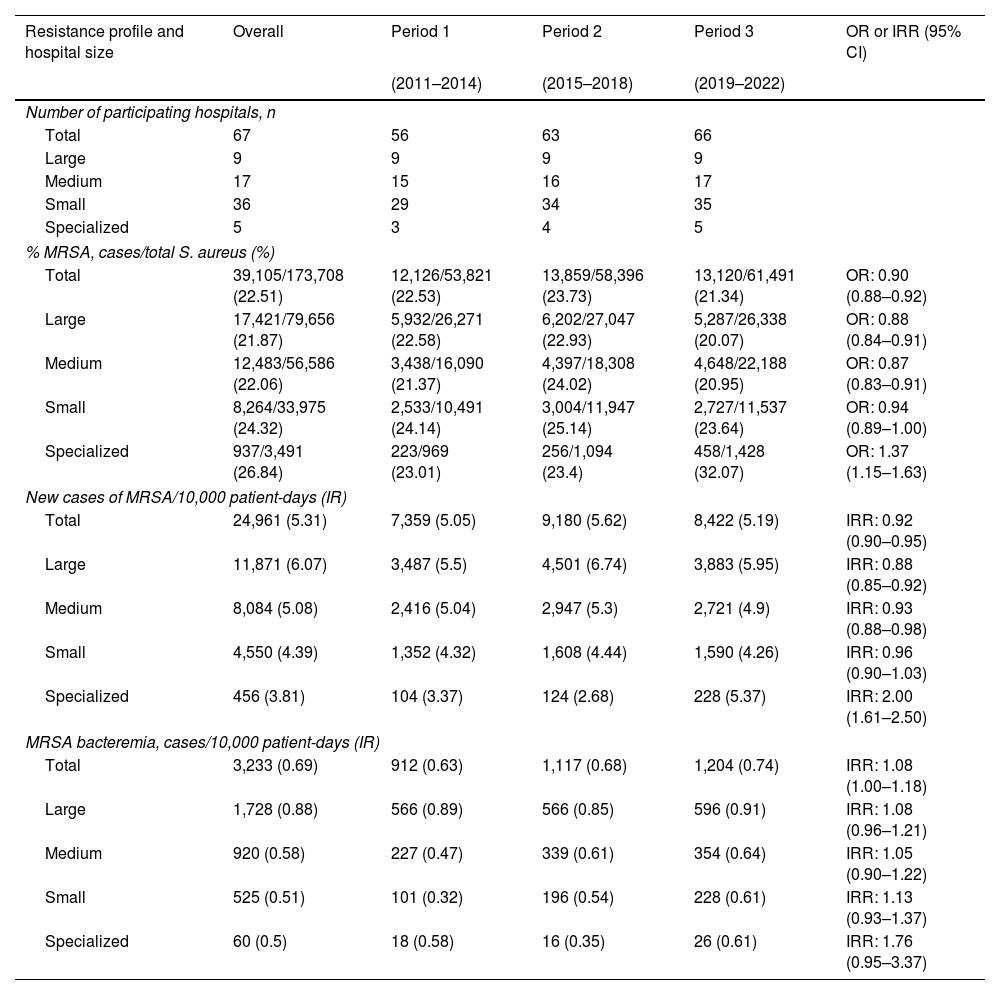

ResultsMethicillin-resistant S. aureusThere were 67 participating hospitals collecting MRSA data. Table 1 and Fig. 1 provide data on MRSA metrics sorted by hospital size and study period (2011–2014, 2015–2018, 2019–2022). Overall, MRSA rate showed slight variability across the periods, with a minor decrease from 22.53% to 21.34%. This decrease was mainly observed in large and medium-sized hospitals, while specialized hospitals showed a notable increase from 23.01% to 32.07% and the small hospitals displayed relatively stable rates. The overall incidence rate of new cases of MRSA slightly increased from 5.05 per 10,000 patient-days in 2011–2014 to 5.19 in 2019–2022. Again, specialized hospitals had a marked increase, particularly in the 2019–2022 period. For MRSA bacteremia, the incidence rate varied over time from 0.63 to 0.74 per 10,000 patient-days in all hospital groups during the same periods. Characteristics of 3473 cases with hospital-acquired MRSA in clinical samples were collected across periods: period 1 (2012–2017:1889 cases) and period 2 (2018–2022:1584 cases), shown in Table S5. Key findings include a reduction in the median age in period 2. Additionally, there was a significant increase in the proportion of cases reported in small hospitals, rising from 15.6% to 23.5% between periods, particularly in medical wards. Finally, respiratory samples were the most common clinical source of MRSA in both periods, although their relative proportion decreased. The time from hospital admission to the first positive MRSA sample was less than 10 days in both periods.

Metrics for MRSA according to study period and type of hospital. (a) Rate of MRSA among S. aureus isolates. (b) Incidence rate of new cases of MRSA/10,000 patient-days. Incidence rate of MRSA bacteremia by hospital size.

| Resistance profile and hospital size | Overall | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | OR or IRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2011–2014) | (2015–2018) | (2019–2022) | |||

| Number of participating hospitals, n | |||||

| Total | 67 | 56 | 63 | 66 | |

| Large | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| Medium | 17 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

| Small | 36 | 29 | 34 | 35 | |

| Specialized | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| % MRSA, cases/total S. aureus (%) | |||||

| Total | 39,105/173,708 (22.51) | 12,126/53,821 (22.53) | 13,859/58,396 (23.73) | 13,120/61,491 (21.34) | OR: 0.90 (0.88–0.92) |

| Large | 17,421/79,656 (21.87) | 5,932/26,271 (22.58) | 6,202/27,047 (22.93) | 5,287/26,338 (20.07) | OR: 0.88 (0.84–0.91) |

| Medium | 12,483/56,586 (22.06) | 3,438/16,090 (21.37) | 4,397/18,308 (24.02) | 4,648/22,188 (20.95) | OR: 0.87 (0.83–0.91) |

| Small | 8,264/33,975 (24.32) | 2,533/10,491 (24.14) | 3,004/11,947 (25.14) | 2,727/11,537 (23.64) | OR: 0.94 (0.89–1.00) |

| Specialized | 937/3,491 (26.84) | 223/969 (23.01) | 256/1,094 (23.4) | 458/1,428 (32.07) | OR: 1.37 (1.15–1.63) |

| New cases of MRSA/10,000 patient-days (IR) | |||||

| Total | 24,961 (5.31) | 7,359 (5.05) | 9,180 (5.62) | 8,422 (5.19) | IRR: 0.92 (0.90–0.95) |

| Large | 11,871 (6.07) | 3,487 (5.5) | 4,501 (6.74) | 3,883 (5.95) | IRR: 0.88 (0.85–0.92) |

| Medium | 8,084 (5.08) | 2,416 (5.04) | 2,947 (5.3) | 2,721 (4.9) | IRR: 0.93 (0.88–0.98) |

| Small | 4,550 (4.39) | 1,352 (4.32) | 1,608 (4.44) | 1,590 (4.26) | IRR: 0.96 (0.90–1.03) |

| Specialized | 456 (3.81) | 104 (3.37) | 124 (2.68) | 228 (5.37) | IRR: 2.00 (1.61–2.50) |

| MRSA bacteremia, cases/10,000 patient-days (IR) | |||||

| Total | 3,233 (0.69) | 912 (0.63) | 1,117 (0.68) | 1,204 (0.74) | IRR: 1.08 (1.00–1.18) |

| Large | 1,728 (0.88) | 566 (0.89) | 566 (0.85) | 596 (0.91) | IRR: 1.08 (0.96–1.21) |

| Medium | 920 (0.58) | 227 (0.47) | 339 (0.61) | 354 (0.64) | IRR: 1.05 (0.90–1.22) |

| Small | 525 (0.51) | 101 (0.32) | 196 (0.54) | 228 (0.61) | IRR: 1.13 (0.93–1.37) |

| Specialized | 60 (0.5) | 18 (0.58) | 16 (0.35) | 26 (0.61) | IRR: 1.76 (0.95–3.37) |

IR: incidence rate; OR: odds ratio; IRR: incidence rate ratio; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

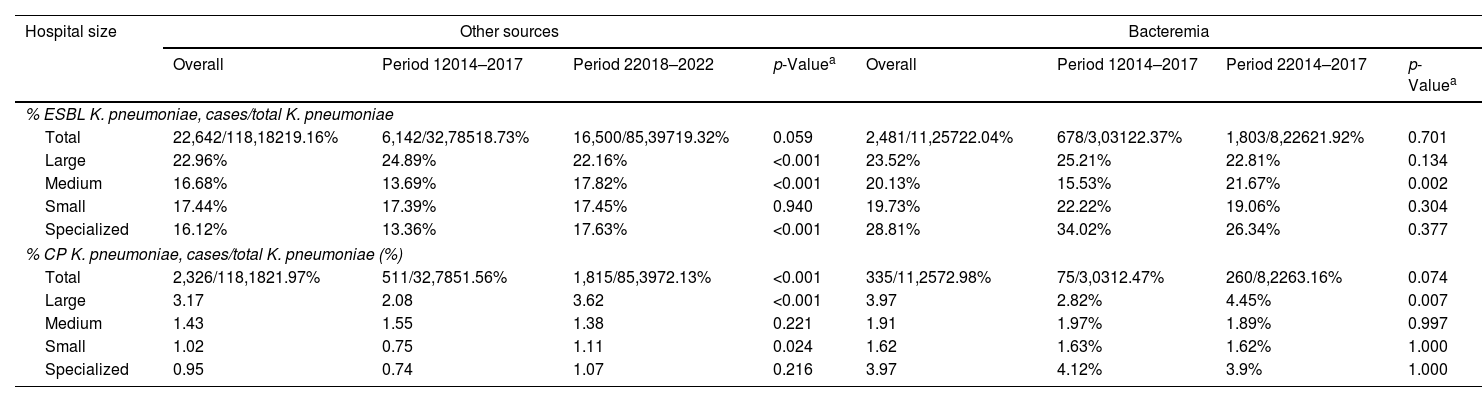

Data was collected from 67 hospitals, 60 hospitals participating in the first period (2014–2017) and 66 in the second period (2018–2022). Rates of ESBL-producing and CR-K. pneumoniae isolates by hospital group and infection source are shown in Table 2. The overall rate of ESBL isolates from bloodstream and other sources remained stable between both periods. However, there was notable differences by hospital group: large hospitals showed a decrease, while medium and specialized hospitals observed increases. The CR-K. pneumoniae isolates rate from bloodstream infections and from other sources increased significantly from period 1 (2014–2017) to period 2 (2018–2022). The increase was most pronounced in large and small hospitals, while medium sized and specialized hospitals had lower and more stable rates.

Rates of ESBL-producing and carbapenemase producing K. pneumoniae according to hospital size and source of infection.

| Hospital size | Other sources | Bacteremia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Period 12014–2017 | Period 22018–2022 | p-Valuea | Overall | Period 12014–2017 | Period 22014–2017 | p-Valuea | |

| % ESBL K. pneumoniae, cases/total K. pneumoniae | ||||||||

| Total | 22,642/118,18219.16% | 6,142/32,78518.73% | 16,500/85,39719.32% | 0.059 | 2,481/11,25722.04% | 678/3,03122.37% | 1,803/8,22621.92% | 0.701 |

| Large | 22.96% | 24.89% | 22.16% | <0.001 | 23.52% | 25.21% | 22.81% | 0.134 |

| Medium | 16.68% | 13.69% | 17.82% | <0.001 | 20.13% | 15.53% | 21.67% | 0.002 |

| Small | 17.44% | 17.39% | 17.45% | 0.940 | 19.73% | 22.22% | 19.06% | 0.304 |

| Specialized | 16.12% | 13.36% | 17.63% | <0.001 | 28.81% | 34.02% | 26.34% | 0.377 |

| % CP K. pneumoniae, cases/total K. pneumoniae (%) | ||||||||

| Total | 2,326/118,1821.97% | 511/32,7851.56% | 1,815/85,3972.13% | <0.001 | 335/11,2572.98% | 75/3,0312.47% | 260/8,2263.16% | 0.074 |

| Large | 3.17 | 2.08 | 3.62 | <0.001 | 3.97 | 2.82% | 4.45% | 0.007 |

| Medium | 1.43 | 1.55 | 1.38 | 0.221 | 1.91 | 1.97% | 1.89% | 0.997 |

| Small | 1.02 | 0.75 | 1.11 | 0.024 | 1.62 | 1.63% | 1.62% | 1.000 |

| Specialized | 0.95 | 0.74 | 1.07 | 0.216 | 3.97 | 4.12% | 3.9% | 1.000 |

Period 1 (2014–2017) included 60 hospitals.

Period 2 (2018–2022) included 66 hospitals.

ESBL: extended-spectrum β-lactamase; CP: carbapenemase-producing.

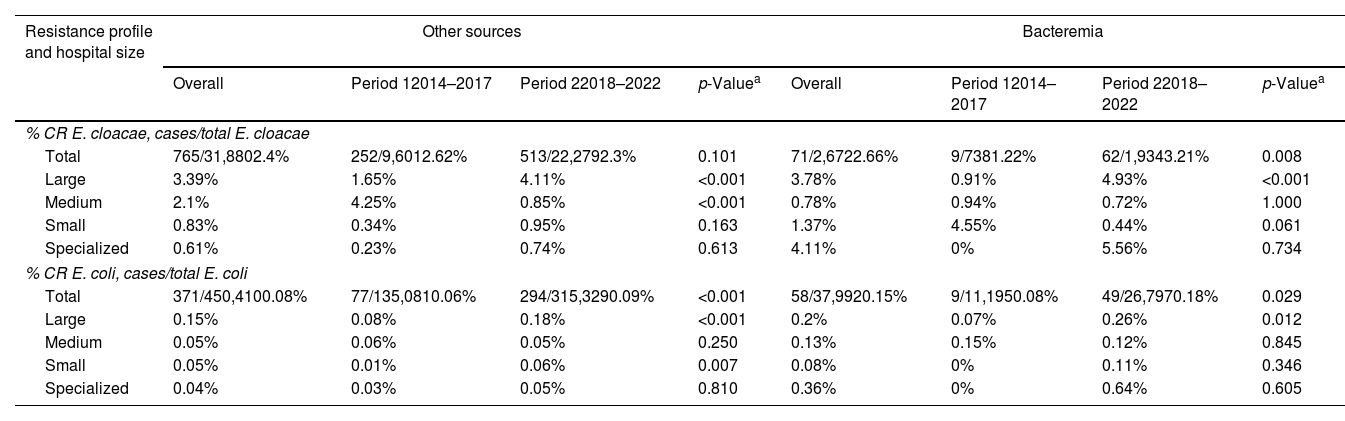

Data was collected from 67 hospitals, with 60 hospitals participating in the first period (2014–2017) and 66 in the second (2018–2022) is shown in Table 3. Across the entire study period, 765 out of 31,880 of E. cloacae isolates were CR, resulting in an overall rate of 2.4%. The rate of CR-E. cloacae isolates from patients with bacteremia was 2.66%, with a statistically significant increase from 1.22% in the first period to 3.21% in the second period, mainly in large hospitals. The overall rate of CR-E. coli was 0.08%, increasing from 0.08% in period 1 to 0.18% in period 2 for bloodstream infections and from 0.06 to 0.09% for other sources.

Rates of carbapenemase-producing E. cloacae and E. coli according to source of infection and hospital group.

| Resistance profile and hospital size | Other sources | Bacteremia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Period 12014–2017 | Period 22018–2022 | p-Valuea | Overall | Period 12014–2017 | Period 22018–2022 | p-Valuea | |

| % CR E. cloacae, cases/total E. cloacae | ||||||||

| Total | 765/31,8802.4% | 252/9,6012.62% | 513/22,2792.3% | 0.101 | 71/2,6722.66% | 9/7381.22% | 62/1,9343.21% | 0.008 |

| Large | 3.39% | 1.65% | 4.11% | <0.001 | 3.78% | 0.91% | 4.93% | <0.001 |

| Medium | 2.1% | 4.25% | 0.85% | <0.001 | 0.78% | 0.94% | 0.72% | 1.000 |

| Small | 0.83% | 0.34% | 0.95% | 0.163 | 1.37% | 4.55% | 0.44% | 0.061 |

| Specialized | 0.61% | 0.23% | 0.74% | 0.613 | 4.11% | 0% | 5.56% | 0.734 |

| % CR E. coli, cases/total E. coli | ||||||||

| Total | 371/450,4100.08% | 77/135,0810.06% | 294/315,3290.09% | <0.001 | 58/37,9920.15% | 9/11,1950.08% | 49/26,7970.18% | 0.029 |

| Large | 0.15% | 0.08% | 0.18% | <0.001 | 0.2% | 0.07% | 0.26% | 0.012 |

| Medium | 0.05% | 0.06% | 0.05% | 0.250 | 0.13% | 0.15% | 0.12% | 0.845 |

| Small | 0.05% | 0.01% | 0.06% | 0.007 | 0.08% | 0% | 0.11% | 0.346 |

| Specialized | 0.04% | 0.03% | 0.05% | 0.810 | 0.36% | 0% | 0.64% | 0.605 |

Overall period (2014–2022) included 67 hospitals: 9 large hospitals, 17 small hospitals, 36 medium-sized hospitals and 5 specialized hospitals.

Period 1 (2014–2017) included 60 hospitals: 9 large hospitals, 16 small hospitals, 31 medium-sized hospitals and 4 specialized hospitals.

Period 2 (2018–2022) included 66 hospitals: 9 large hospitals, 17 small hospitals, 35 medium-sized hospitals and 5 specialized hospitals.

ESBL: extended-spectrum β-lactamase; CP: carbapenemase-producing.

Table S6 presents the distribution of type of carbapenemases among K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, and E. coli, comparing period 1 (2014–2017) and period 2 (2018–2022). The OXA48 was the most common, accounting for 67.2% overall, slightly increasing from 66.3% in period 1 to 67.5% in period 2. The VIM also rose from 13% to 19.3% between periods, NDM remained stable at around 6.9%, and KPC rose from 4.6% to 13.3%. There were significant differences in carbapenemase distribution between the two periods for most organisms, especially for K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae.

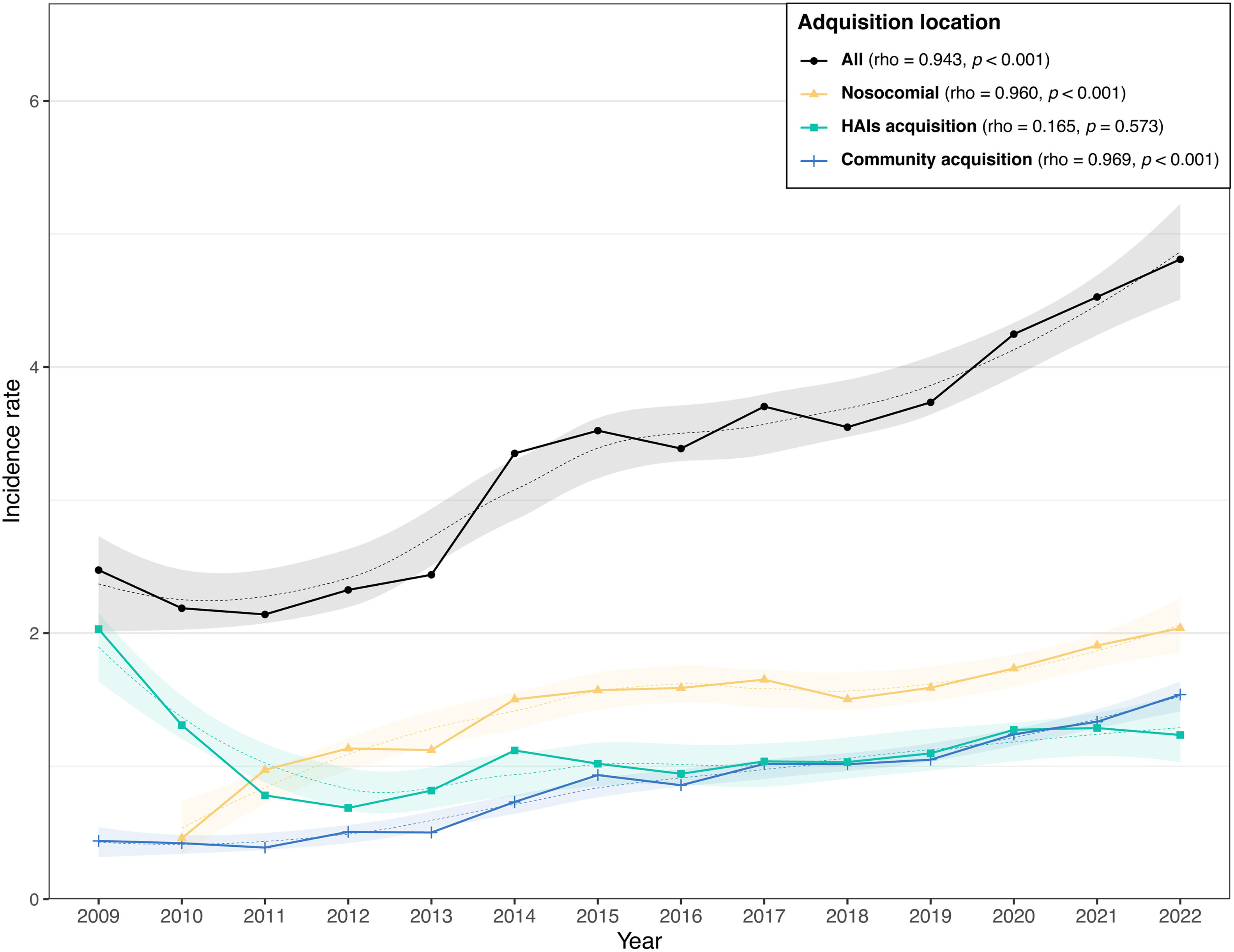

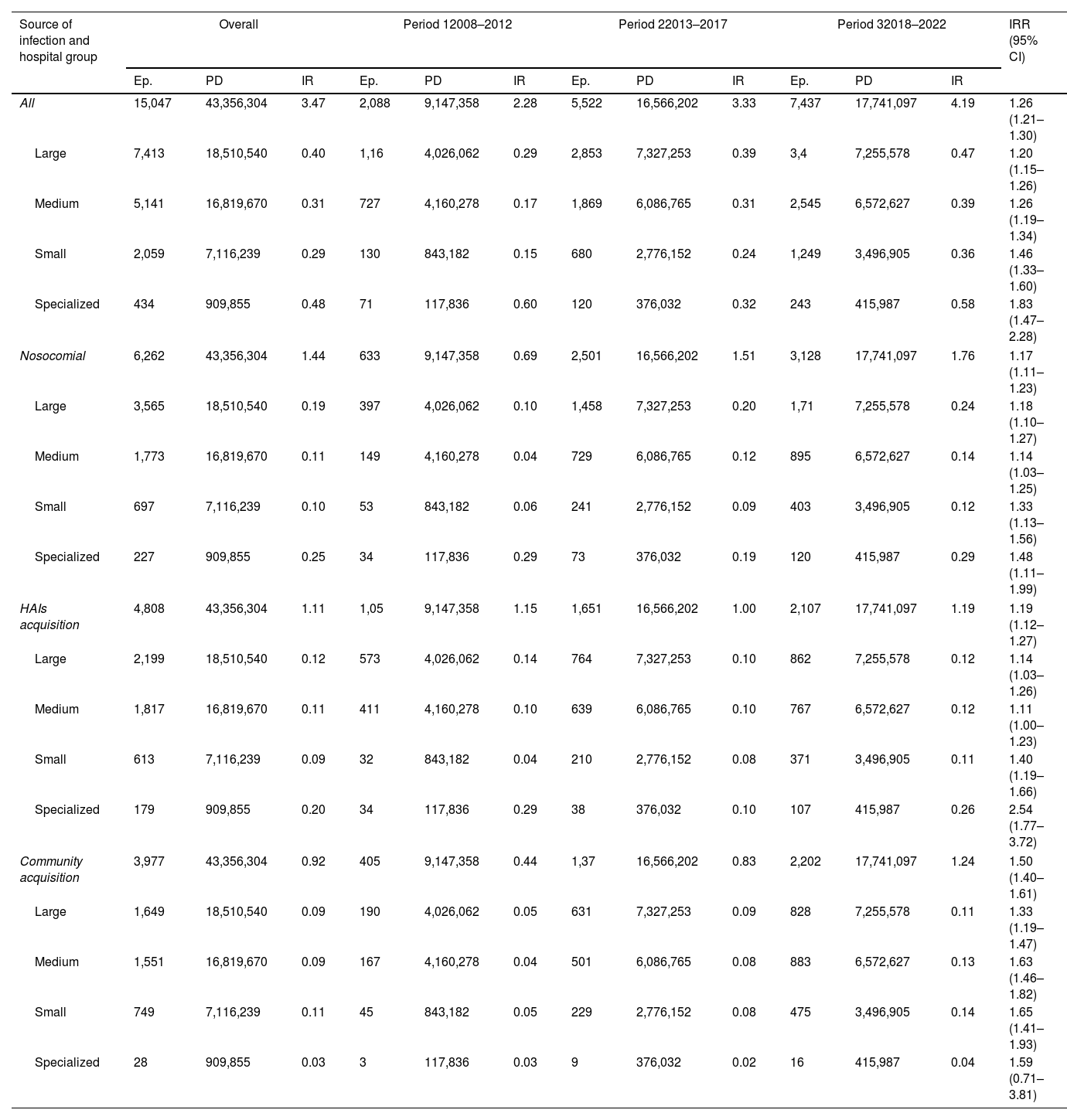

Clostridioides difficile infectionsThe characteristics of 15,047 CDI reported by 62 hospitals across the three periods, period 1 (2008–2012), period 2 (2013–2017), and period 3 (2018–2022) are shown in Table S7. The median age of patients with CDI decreased from 75 years in period 1 to 72 years in period 3. Large hospitals reported 49.3% of cases, medium-sized hospitals 34.2%, and smaller hospitals 13.7%, while the percentage in specialized hospitals group was 2.9%. The proportion of cases reported by larger hospitals fell from 55.6% to 45.7% across periods, while smaller hospitals saw an increase from 6.2% to 16.8%.

The acquisition of CDI was hospital-acquired in 41.6% of cases, non-nosocomial healthcare-associated in 32% and community-acquired in 26.4%. Community-acquired cases rose from 19.4% in period 1 to 29.6% in period 3; hospital-acquired CDI increased from 30.3% to 42.1%, and non-nosocomial healthcare-related decreases from 50.3% to 28.3% across periods. Fig. 2 and Table 4 demonstrate a significant increase in CDI incidence from 2.28 cases per 10,000 patient-days in period 1 (2008–2012) to 4.19 in period 3 (2018–2022). The trend was maintained across nosocomial CDI (from 0.46 in 2010 to 1.94 in 2022) and community CDI (from 0.44 to 1.46). Table S7 shows that the CDI incidence rate rose from 3.33 cases per 10,000 patient-days (2013–2017) to 4.19 cases (2018–2022), regardless of hospital size or CDI origin.

Incidence rate per 10,000 patient-days of Clostridioides difficile infections diagnosed at VINCat hospitals by acquisition and hospital size.

| Source of infection and hospital group | Overall | Period 12008–2012 | Period 22013–2017 | Period 32018–2022 | IRR (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ep. | PD | IR | Ep. | PD | IR | Ep. | PD | IR | Ep. | PD | IR | ||

| All | 15,047 | 43,356,304 | 3.47 | 2,088 | 9,147,358 | 2.28 | 5,522 | 16,566,202 | 3.33 | 7,437 | 17,741,097 | 4.19 | 1.26 (1.21–1.30) |

| Large | 7,413 | 18,510,540 | 0.40 | 1,16 | 4,026,062 | 0.29 | 2,853 | 7,327,253 | 0.39 | 3,4 | 7,255,578 | 0.47 | 1.20 (1.15–1.26) |

| Medium | 5,141 | 16,819,670 | 0.31 | 727 | 4,160,278 | 0.17 | 1,869 | 6,086,765 | 0.31 | 2,545 | 6,572,627 | 0.39 | 1.26 (1.19–1.34) |

| Small | 2,059 | 7,116,239 | 0.29 | 130 | 843,182 | 0.15 | 680 | 2,776,152 | 0.24 | 1,249 | 3,496,905 | 0.36 | 1.46 (1.33–1.60) |

| Specialized | 434 | 909,855 | 0.48 | 71 | 117,836 | 0.60 | 120 | 376,032 | 0.32 | 243 | 415,987 | 0.58 | 1.83 (1.47–2.28) |

| Nosocomial | 6,262 | 43,356,304 | 1.44 | 633 | 9,147,358 | 0.69 | 2,501 | 16,566,202 | 1.51 | 3,128 | 17,741,097 | 1.76 | 1.17 (1.11–1.23) |

| Large | 3,565 | 18,510,540 | 0.19 | 397 | 4,026,062 | 0.10 | 1,458 | 7,327,253 | 0.20 | 1,71 | 7,255,578 | 0.24 | 1.18 (1.10–1.27) |

| Medium | 1,773 | 16,819,670 | 0.11 | 149 | 4,160,278 | 0.04 | 729 | 6,086,765 | 0.12 | 895 | 6,572,627 | 0.14 | 1.14 (1.03–1.25) |

| Small | 697 | 7,116,239 | 0.10 | 53 | 843,182 | 0.06 | 241 | 2,776,152 | 0.09 | 403 | 3,496,905 | 0.12 | 1.33 (1.13–1.56) |

| Specialized | 227 | 909,855 | 0.25 | 34 | 117,836 | 0.29 | 73 | 376,032 | 0.19 | 120 | 415,987 | 0.29 | 1.48 (1.11–1.99) |

| HAIs acquisition | 4,808 | 43,356,304 | 1.11 | 1,05 | 9,147,358 | 1.15 | 1,651 | 16,566,202 | 1.00 | 2,107 | 17,741,097 | 1.19 | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) |

| Large | 2,199 | 18,510,540 | 0.12 | 573 | 4,026,062 | 0.14 | 764 | 7,327,253 | 0.10 | 862 | 7,255,578 | 0.12 | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) |

| Medium | 1,817 | 16,819,670 | 0.11 | 411 | 4,160,278 | 0.10 | 639 | 6,086,765 | 0.10 | 767 | 6,572,627 | 0.12 | 1.11 (1.00–1.23) |

| Small | 613 | 7,116,239 | 0.09 | 32 | 843,182 | 0.04 | 210 | 2,776,152 | 0.08 | 371 | 3,496,905 | 0.11 | 1.40 (1.19–1.66) |

| Specialized | 179 | 909,855 | 0.20 | 34 | 117,836 | 0.29 | 38 | 376,032 | 0.10 | 107 | 415,987 | 0.26 | 2.54 (1.77–3.72) |

| Community acquisition | 3,977 | 43,356,304 | 0.92 | 405 | 9,147,358 | 0.44 | 1,37 | 16,566,202 | 0.83 | 2,202 | 17,741,097 | 1.24 | 1.50 (1.40–1.61) |

| Large | 1,649 | 18,510,540 | 0.09 | 190 | 4,026,062 | 0.05 | 631 | 7,327,253 | 0.09 | 828 | 7,255,578 | 0.11 | 1.33 (1.19–1.47) |

| Medium | 1,551 | 16,819,670 | 0.09 | 167 | 4,160,278 | 0.04 | 501 | 6,086,765 | 0.08 | 883 | 6,572,627 | 0.13 | 1.63 (1.46–1.82) |

| Small | 749 | 7,116,239 | 0.11 | 45 | 843,182 | 0.05 | 229 | 2,776,152 | 0.08 | 475 | 3,496,905 | 0.14 | 1.65 (1.41–1.93) |

| Specialized | 28 | 909,855 | 0.03 | 3 | 117,836 | 0.03 | 9 | 376,032 | 0.02 | 16 | 415,987 | 0.04 | 1.59 (0.71–3.81) |

Period 1: 2008–2012; period 2: 2013–2017; period 3: 2018–2022; Ep.: episodes; PD: patient-days; IR: incidence rate; IRR: incidence rate ratio.

This study, which examines the trends in the incidence of major MDROs and CDIs across more than 60 hospitals in Catalonia, highlights the value of robust, long-term surveillance systems. The findings provide insights into baseline rates, their evolution over time, and the effectiveness of infection control measures. Moreover, hospitals can use these data to benchmark their performance and adapt infection prevention strategies accordingly.

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus continues to be a significant public health concern due to its association with high morbidity and mortality, especially in patients with bacteremia. Our study observed a slight decline in the rate of MRSA across the study period. This trend aligns with broader European data, which shows a reduction in MRSA prevalence in several countries.1 While MRSA rates in larger hospitals decreased, specialized hospitals experienced an increase, possibly due to the higher admission rates of high-risk or colonized patients, such as those with frequent hospitalizations or chronic condicitions.8 The rise in bacteremia cases between the two study periods suggests a need for further investigation into infection sources and control strategies.9 Despite overall improvements in infection control, such as decolonization protocols, the figure of MRSA bacteremia underscores the necessity for ongoing surveillance and tailored interventions, particularly in smaller hospitals and specialized centers.10

The stability of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae rates at around 22% of cases of bacteremia is consistent with other European data, where rates vary significantly by region.1 However, the rise in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, though still relatively low, is alarming. The increase in carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. cloacae reflects global and broader European trends, where carbapenem resistance has steadily increased, especially in Southern and Eastern European countries. This increase signals the need for more aggressive infection control strategies, including stricter antibiotic stewardship and enhanced isolation procedures for affected patients.11 The widespread presence of OXA-48 carbapenemase, the most prevalent in our study, further underscores the necessity of surveillance to track the spread of specific resistance mechanisms.

Our findings reveal a significant increase in CDI incidence from 2009 to 2022, with a consistent rise across nosocomial and community-acquired cases. This trend contrasts with reports from other regions where CDI incidence has stabilized or decreased.12 Improved diagnostic tools, introduced in 2011, may partly explain the rise, but other factors, including increased antibiotic use and an aging patient population, are likely to contribute to the higher rates.13,14 The relative increase in the burden of CDI cases diagnosed in smaller hospitals makes it necessary to improve preventive measures, including antibiotic stewardship programmmes, in such centers. The increase in community-acquired CDI is particularly concerning, suggesting the need for more comprehensive preventive strategies beyond the hospital setting. This could involve enhanced antimicrobial stewardship programs, better hygiene practices in community healthcare environments, and public education about CDI transmission and prevention.14

The results from the VINCat Program offer critical insights into the evolution of MDROs and CDI in Catalonia's hospitals. However, the rise in carbapenemase-producing organisms and the persistence of MRSA and CDI in certain settings indicate that current infection control measures must be adapted and intensified, especially in smaller and specialized hospitals. Tailored interventions focusing on high-risk patient populations, more effective decolonization strategies, and comprehensive antibiotic stewardship programs are essential.

Further research should explore the long-term impact of COVID-19 on MDRO and CDI incidence. The pandemic likely influenced infection control practices and antibiotic usage in ways that are not yet fully understood. Changes in infection control practices and supply shortages were identified in facilities with eMDRO outbreaks during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and might have contributed to eMDRO transmission. Jeon et al. observed an increase in the prevalence of infections caused by MDRO isolates associated with a higher antibiotic consumption.15 Other authors observed a reduction in the incidence density in the health-care associated CDI because a strict infection control measures including reinforced cleansing procedures.16,17 Ongoing surveillance will be crucial in identifying whether trends observed during the pandemic will persist.

Our study has several strengths that contribute to its robustness and relevance. First, the longitudinal design spanning 15 years provides a comprehensive analysis of trends in MDROs and CDI. This extended timeframe allows for the identification of meaningful changes and long-term patterns. Second, the inclusion of data from 67 hospitals, representing diverse settings in terms of size and specialization, enhances the generalizability of the findings. By stratifying results based on hospital size, the study captures variability across different healthcare environments. Third, the use of standardized surveillance protocols across all participating centers ensures consistency in data collection and reporting, minimizing methodological bias and enabling reliable comparisons over time. Fourth, the study covers multiple key MDROs and CDI, providing a holistic view of antimicrobial resistance and healthcare-associated infections. This comprehensive approach makes the findings particularly valuable for guiding infection control strategies. Finally, as part of the VINCat Program, the study contributes valuable regional data on antimicrobial resistance trends in Catalonia, offering insights that can inform both local and broader infection control policies. Our study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. While grouping hospitals by size reduces the impact of outliers, we did not perform adjusted analyses to account for potential center-specific surveillance variations. This may have introduced bias, particularly if certain hospitals had significantly higher or lower infection rates. The study does not explore in detail the underlying factors driving the observed trends, such as the implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs or specific infection control measures. This limits our ability to directly attribute changes in incidence to particular interventions. Finally, the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on antimicrobial resistance trends and hospital-acquired infections is not fully addressed. Changes in infection control practices, resource allocation, and antibiotic usage during the pandemic may have influenced the results, and further investigation is needed to assess these effects comprehensively.

In conclusion, the VINCat Program's surveillance system has provided invaluable data on MDROs and CDI in Catalonia. These insights should guide future infection control efforts within individual hospitals and the broader healthcare system.

FundingThe VINCat Programme is supported by public funding from the Catalan Health Service, Department of Health, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

Data availabilityRestrictions apply to the availability of these data, which belong to a national database and are not publicly available. Data was obtained from VINCat and are only available with the permission of the VINCat Technical Committee.

Iñaki Catalan Gómez, Gloria Trujillo Isern, Althaia, Xarxa Assistencial Universitària de Manresa. Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Manresa; Mireia Duch Pedret, Teresa Falgueras Sureda, Badalona Serveis Assistencials; M. de Gracia García Ramírez, Francisco José Vargas-Machuca Fernández, Centre MQ Reus; Grethel Rodríguez Cabalé, Natalia Juan Serra, Centro Médico Teknon; Teresa Domenech Forcadell, Juan Ayala Cervantes, Clínica Terres de l’Ebre; Eva Palau Gil, Clinica Girona; Eduardo Sáez Huerta, Clínica NovAliança de Lleida; Anna Vilamala Bastarras, Maria Navarro Aguirre, Consorci hospitalari de Vic; María Cuscó Esteve, Laura Linares Gonzalez, Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedes i Garraf. Hospital Alt Penedés; David Blancas Altabella, Esther Moreno Rubio, Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedes i Garraf. Hospital Sant Camil; Juan Serrais Benavente, Judit Santamaria Rodriguez, Consorci Sanitari de l’Anoia. Hospital d’Igualada; Laura Grau Palafox, Marta Andrés Santamaria, Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa; Sara Gil Alvarez, Ines Valle T-Figueras, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme. Hospital de Mataró; Ana Coloma Conde, Consorci Sanitari Integral. Hospital Universitari Sant Joan Despi. Moises Broggi; Susanna Camps Carmona, Silvia Capilla Rubio, Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí de Sabadell; Ludivina Ibáñez Soriano, Espitau Val d’Aran; Guillem Vidal Escudero, Rosalia Karine Santos da Silva, Fundació Hospital de l’Esperit Sant; Carles Alonso-Tarrés, Carla Benjumea Moreno, Fundació Puigvert; M. Teresa Ros Prat, M. Carmen Perez-Ciriza Villacampa, Fundació Sant Hospital La Seu d’Urgell; Milagros Herranz Adeva, Juan Pablo Horcajada Gallego, Hoapital del Mar; Ricardo Gabriel Zules Oña, Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta; Manel Panisello Bertomeu, Hospital comarcal d’Amposta; Angeles Garcia Flores, Carme Gallés, Hospital Comarcal de Blanes; Joan Galbany Padrós, Claudia Miralles Adell, Hospital Comarcal de Móra d’Ebre; Arantzazu Mera Fidalgo, Nuria Torrellas Bertran, Hospital de Palamos; Yolanda Meije Castillo, Jaume Llaveria Marcual, Hospital de Barcelona.SCIAS; Anna Martinez Sibat, Rosa Laborda Galvez, Hospital de Campdevànol; Mireia Iglesias, Carme Mora Maruny, Hospital de Figueres; Marta Piriz Marabajan, Maria Alba Rivera Martínez, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; Josep Rebull Fatsini, Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta; Ana Lerida Urteaga, Lidia Martín González, Hospital de Viladecans; Rosa Laplace Enguídanos, Lluis Òscar Jorbà, Hospital Del Vendrell; Maria Montserrat Blasco Afonso, Ester Sanfeliu Riera, Hospital d’Olot Comarcal de la Garrotxa; Clara Sala Jofre, Hospital Dos de Maig, Consorci Sanitari Integral; Elisabet Lerma Chippirraz, Mayuli Armas Cruz, Hospital General de Granollers; Marta Milián Sanz, Hospital Pius de Valls; Mireia Saballs Nadal, Jessica Galvez, Hospital QuironSalud Barcelona; Roser Ferrer i Aguilera, Angeles Garcia Flores, Hospital Sant Jaume de Calella; Irene Sánchez Rodriguez, Fina Guimerà, Hospital Sant Rafael; Núria Bosch Ros, Hospital Sta. Caterina Girona; Frederic Ballester Bastardie, Isabel Pujol Bajador, Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus; María Ramirez Hidalgo, Mercè Garcia Gonzàlez, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida; Carmen Ardanuy, Fe Tubau Quintano, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge; Pilar de la Cruz Sole, Ivett Suarez, Hospital Universitari Dexeus; Roger Malo Barres, Montserrat Olsina, Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya; Jun Hao Wang, Montse Giménez Pérez, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol; María Dolores Guerrero Torres, Montserrat Olna Cabases, Hospital universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona; Maria López Sánchez, Esther Calbo Sebastian, Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa; Rosa Coll Colell, Natacha Recio Prieto, Hospital Universitari Sagrat Cor; Alba Guitard Quer, Ivan Prats, Hospital Universitari Santa Maria; Belen Viñado Perez, Nieves Larrosa Escartin, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron; Laura Cabrera Jaime, Institut Català d’Oncologia Badalona; Jessica Rodríguez Garcia, Institut Català d’Oncologia Girona; M. Carmen Eito Navasal, Institut Català d’Oncologia L’Hospitalet de Llobregat; Mariona Secanell Espluga, Institut Guttmann; Vicens Diaz-Brito Fernandez, Araceli González-Cuevas, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan De Déu. Hospital de Sant Boi; Mariona Xercavins, Emma Padilla Esteba, Virginia Plasencia Miguel and Rosa Rubio Casino, Catlab; Ariadna Hernandez Paraire and Elisabet Folch, Centre d’anàlisis Girona; Anna Llimós Fabregas and Ester Moreno, Cerba internacional; Yuliya Poliakova and Clara Marco, Consorci Laboratori Intercomarcal; Frederic Gómez Bertomeu, Laboratori Clinic ICS Camp de Tarragona; Mar Olga Perez Moreno, Laboratori Clínic ICS-Terres de l’Ebre; Ester Clapés Sánchez, Laboratori Clínic Territorial de Girona; Sandra Esteban Cucó and Anna Padrós Fluviá, Laboratòri de Referencia de Catalunya.

The following are the supplementary data to this article: