Fusarium spp. is one of the most ubiquitous filamentous fungal pathogens in the world1. In humans, Fusarium species cause localised, locally invasive or disseminated infections. The main clinical signs include skin compromise, onychomycosis and eye infections such as keratitis and endophthalmitis; the latter may be post-traumatic, due to contamination of contact lenses or due to mould-contaminated ophthalmic solutions, or they may occur in patients with underlying corneal disease who apply topical corticosteroids or use antibiotics2. The most susceptible patients are those with severe neutropenia, in particular severe neutropenia caused by haematologic neoplasms or medicines3.

We report a case of Fusarium spp. fungal infection with skin lesions in a patient with a history of promyelocytic leukaemia with severe neutropenia. The diagnosis and treatment of this infection prevented the dissemination thereof, despite the presence of risk factors.

A 37-year-old man, with promyelocytic leukaemia being treated with tretinoin, 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate, presented a clinical picture of epistaxis and bleeding gums for four days, with no other symptoms. Blood testing revealed a platelet count of 15,000/mm3, and flow cytometry of bone marrow showed relapse of his disease requiring adjustment of his induction chemotherapy.

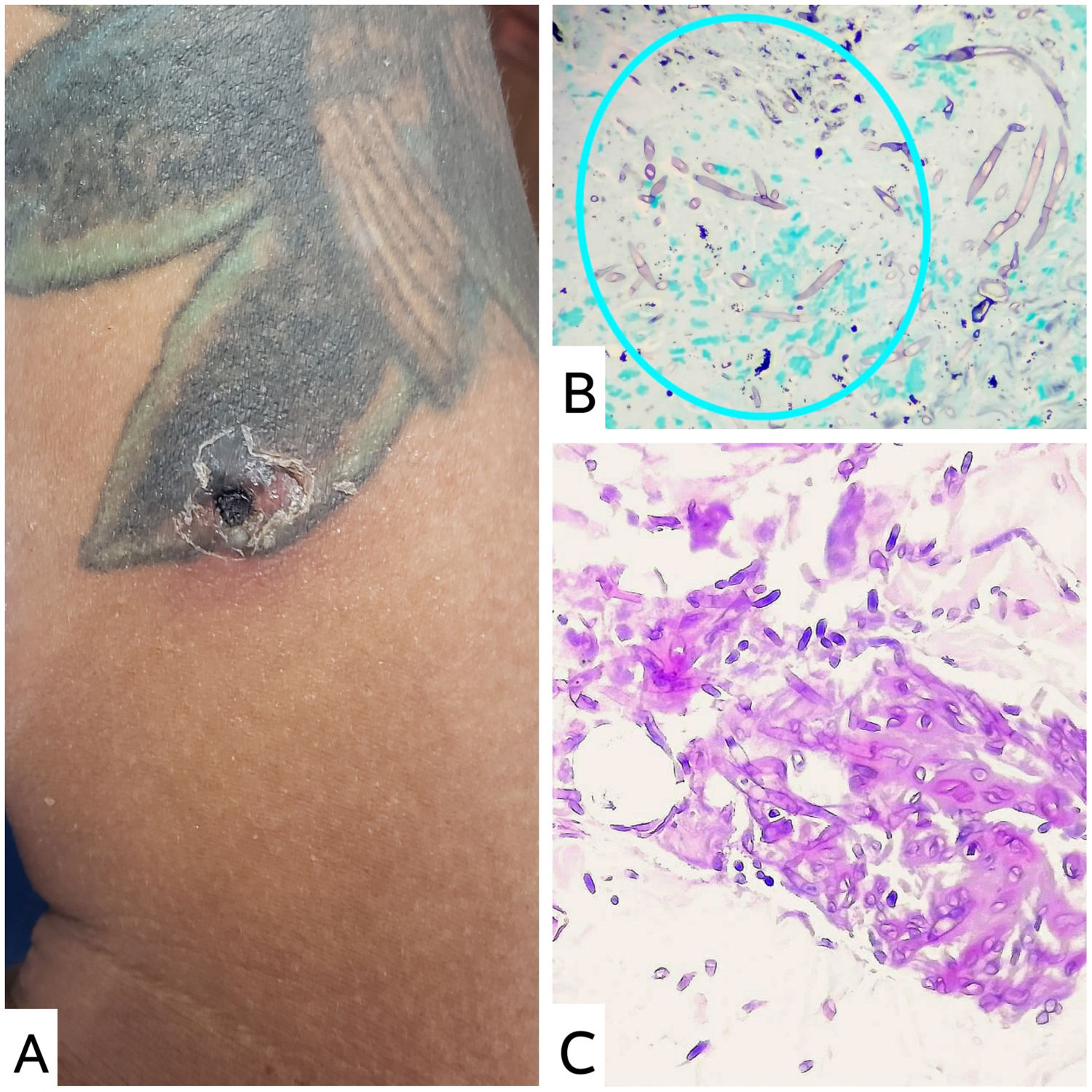

On day 20 of his hospital stay, he had a febrile episode with the onset of oedema and erythema in his left big toe. A single ecthymatous nodule was detected on his left arm; the nodule was necrotic and indurated, with perilesional erythema and pain on palpation, and bounded by a tattoo on that arm. The patient had no history of local puncture or trauma. At that time, a complete blood count showed a neutrophil count of 10/mm3 (Fig. 1A).

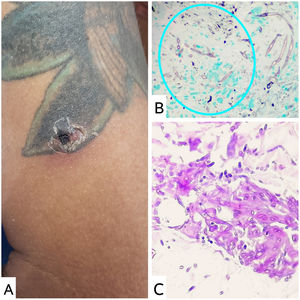

Due to a strong clinical suspicion of a fungal infection such as fusariosis, another hyalohyphomycosis, pheohyphomycosis or mucormycosis, a decision was made to biopsy the skin lesion on the patient's left arm and immediately start treatment with liposomal amphotericin B. The microbiology report for the KOH exam showed septate hyphae with dichotomous branching at 45-degree angles. The histopathology study showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, with abundant mixed dermal inflammatory infiltrate featuring a predominance of mononuclear cells, accompanied by histiocytes and plasma cells. Thin hyaline septate hyphae forming acute angles that stood out with Gomori and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining were detected in the thickness of the sample (Figs. 1B and 1C). Finally, after a week of culture in Sabouraud agar and Mycosel agar media at room temperature (22 °C–25 °C), lactophenol blue staining revealed hyaline septate hyphae with spindle-shaped microconidia and septa, consistent with the hyalohyphomycete Fusarium spp.

A computed tomography scan of the chest, a total abdominal ultrasound and blood cultures showed no evidence of acute fungal or bacterial infection in the blood or other organs.

The patient received treatment with parenteral liposomal amphotericin B for 14 days, with complete resolution of his skin lesions, and continued treatment with oral voriconazole.

The fungus Fusarium spp. is associated with infections in both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients; the most common species are F. solani and F. oxysporum. Immunosuppressed patients account for 70% of cases; most have severe, prolonged neutropenia and/or severe immunodeficiency, haematologic neoplasms or a history of haematopoietic cell transplantation, where fusariosis is usually locally invasive or disseminated4. Some 75% of patients with disseminated fusariosis have dermatological lesions such as purpuric skin nodules with a necrotic centre or lesions similar to ecthyma gangrenosum or digital cellulitis5, with a 43% probability of 90-day survival6.

Localised skin lesions in immunocompromised patients merit special attention, as they can spread. Treatment includes local debridement and the use of topical antifungal agents such as natamycin or amphotericin B before starting systemic therapy. However, in this case, given the early clinical suspicion of a fungal infection and considering the presence of risk factors, a decision was made to start systemic treatment with liposomal amphotericin B and/or azoles to prevent dissemination and associated morbidity and mortality.

Adjuvant treatments such as surgical reduction of infected tissues, removal of venous catheters, granulocyte transfusion and the use of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) have not been shown to be more effective; nevertheless, they are thought to be potentially helpful in patients with a poor prognosis7.

In conclusion, in severely immunosuppressed patients, strong clinical suspicion of fungal infection and early initiation of suitable treatment can prevent fatal outcomes.

Please cite this article as: Guerrero Arias CA, Marulanda Nieto CJ, Díaz Gómez CJ. Infección por Fusarium spp.: importancia de un diagnóstico temprano. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:339–341.