The aim of this study was to know, through a national survey, the methods and techniques used for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori (Hp) in the different Clinical Microbiology Services/Laboratories in Spain, as well as antibiotic resistance data.

MethodsThe survey requested information about the diagnostic methods performed for H. pylori detection in Clinical Microbiology laboratories, including serology, stool antigen, culture from gastric biopsies, and PCR. In addition, the performance of antibiotic susceptibility was collected. Data on the number of samples processed in 2016, positivity of each technique and resistance data were requested. The survey was sent by email (October–December 2017) to the heads of 198 Clinical Microbiology Laboratories in Spain.

ResultsOverall, 51 centres from 29 regions answered the survey and 48/51 provided Hp microbiological diagnostic testing. Concerning the microbiological methods used to diagnose Hp infection, the culture of gastric biopsies was the most frequent (37/48), followed by stool antigen detection (35/48), serology (19/48) and biopsy PCR (5/48). Regarding antibiotic resistance, high resistance rates were observed, especially in metronidazole and clarithromycin (over 33%).

ConclusionCulture of gastric biopsies was the most frequent method for detection of Hp, but the immunochromatographic stool antigen test was the one with which the largest number of samples were analyzed. Nowadays, in Spain, it concerns the problem of increased antibiotic resistance to ‘first-line’ antibiotics.

El objetivo de este trabajo fue conocer, mediante una encuesta nacional, los métodos y técnicas empleados para el diagnóstico de Helicobacter pylori (Hp) en los distintos Servicios/Laboratorios de Microbiología Clínica en España, así como datos de resistencia antibiótica.

MétodosEn la encuesta se preguntaba sobre los métodos de diagnóstico realizados (serología, detección de antígeno en heces, cultivo de biopsias gástricas y PCR) y por la realización de pruebas de sensibilidad antibiótica. También fueron solicitados el número de muestras procesadas en 2016, la positividad de cada técnica empleada y porcentajes de resistencia antibiótica. La encuesta fue enviada por correo electrónico entre octubre y diciembre de 2017 a los responsables de 198 Laboratorios de Microbiología Clínica.

ResultadosEn total, 51 centros de 29 provincias respondieron a la encuesta y 48 de ellos realizaban algún tipo de técnica de diagnóstico de Hp en su laboratorio. En cuanto a las técnicas empleadas, el cultivo de biopsia gástrica fue el más utilizado (37/48), seguido de la detección de antígeno en heces (35/48), la serología (19/48) y la PCR (5/48). Respecto a la sensibilidad antibiótica, se observaron altas tasas de resistencia, especialmente a metronidazol y claritromicina (superiores al 33%).

ConclusiónEl cultivo de biopsia gástrica fue la técnica diagnóstica de Hp utilizada por más centros, mientras que la detección de antígeno en heces mediante inmunocromatografía fue con la que se analizaron el mayor número de muestras. En España, en la actualidad, es preocupante el aumento de resistencia de Hp a antibióticos de ‘primera línea’.

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) is a spiral-shaped, Gram-negative pathogenic bacterium which colonises the mucosa of the human stomach thanks to its mobility and its ability to resist its high acidity. Countries or geographic areas with a low level of socio-economic development have the highest prevalence figures (60%–80% of the adult population is infected with Hp); in areas with a high level of socio-economic development, the infection rate in the adult population is in the range of 30%–50%.1 The highest prevalence is in Africa (79.1%), South America and the Caribbean (63.4%), and the lowest in North America (37.1%) and Oceania (24.4%).2 In Europe, the highest prevalence rates are in southern and eastern countries, such as Portugal and Poland, while the lowest rates are found in the northern countries.3,4 In Spain, several studies estimate the prevalence of Hp to be above 50%2,4 In most cases, Hp infection is asymptomatic, with only a small percentage of people developing clinical manifestations such as: gastritis, peptic ulcer (10%–15% of affected individuals), mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma (1%–3%).5,6

Infection with Hp can be diagnosed by invasive methods (via endoscopy) or non-invasively, with a variety of techniques that can be performed by specialists such as microbiologists, biochemists, pathologists or gastroenterologists. Until now, however, no information was generally available on the Hp diagnostic techniques used in Spanish clinical microbiology laboratories. As regards antibiotic treatment for Hp, the increase in resistance rates to antibiotics considered "first line", such as clarithromycin and metronidazole,7 is a concern in many countries, including here in Spain. In order to better manage treatment guidelines, it is very important for us to know the current antibiotic resistance rate in Spain.

The aim of this project was to obtain data from the different clinical microbiology services/laboratories in Spain on the methods used to diagnose Hp and study sensitivity, and on antibiotic resistance, through a national survey.

MethodsWe prepared the survey aided by the opinions of a panel of 11 microbiologists expert in the field of Hp. We then had the panel evaluate the survey to verify that it worked and was appropriate for the set objectives. The survey was designed using the Google Forms platform and contained 37 sections with both multiple choice and short text questions. The survey sought information about the diagnostic methods used for the detection of Hp in clinical microbiology laboratories in Spain, including serology, stool antigen (Ag) detection, gastric biopsy culture and PCR. It also included questions about testing for antibiotic sensitivity. Data were requested such as the number of samples processed in 2016, positivity rate for each technique used and percentages of antibiotic resistance. The survey also asked about use of the urea breath test and the rapid urease test in gastric biopsy.

The survey link was sent by email from October to December 2017 through the Grupo de Estudio para la Gestión en Microbiología Clínica (GEGMIC) [Study Group for Management in Clinical Microbiology] of the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC) [Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology] to the heads of 198 clinical microbiology laboratories in Spain.

The survey responses were saved directly from Google Forms onto the Google Spreadsheet platform and were exported to Microsoft Excel 2013 for further analysis. For the statistical analysis, we used the OpenEpi software version 3.01.

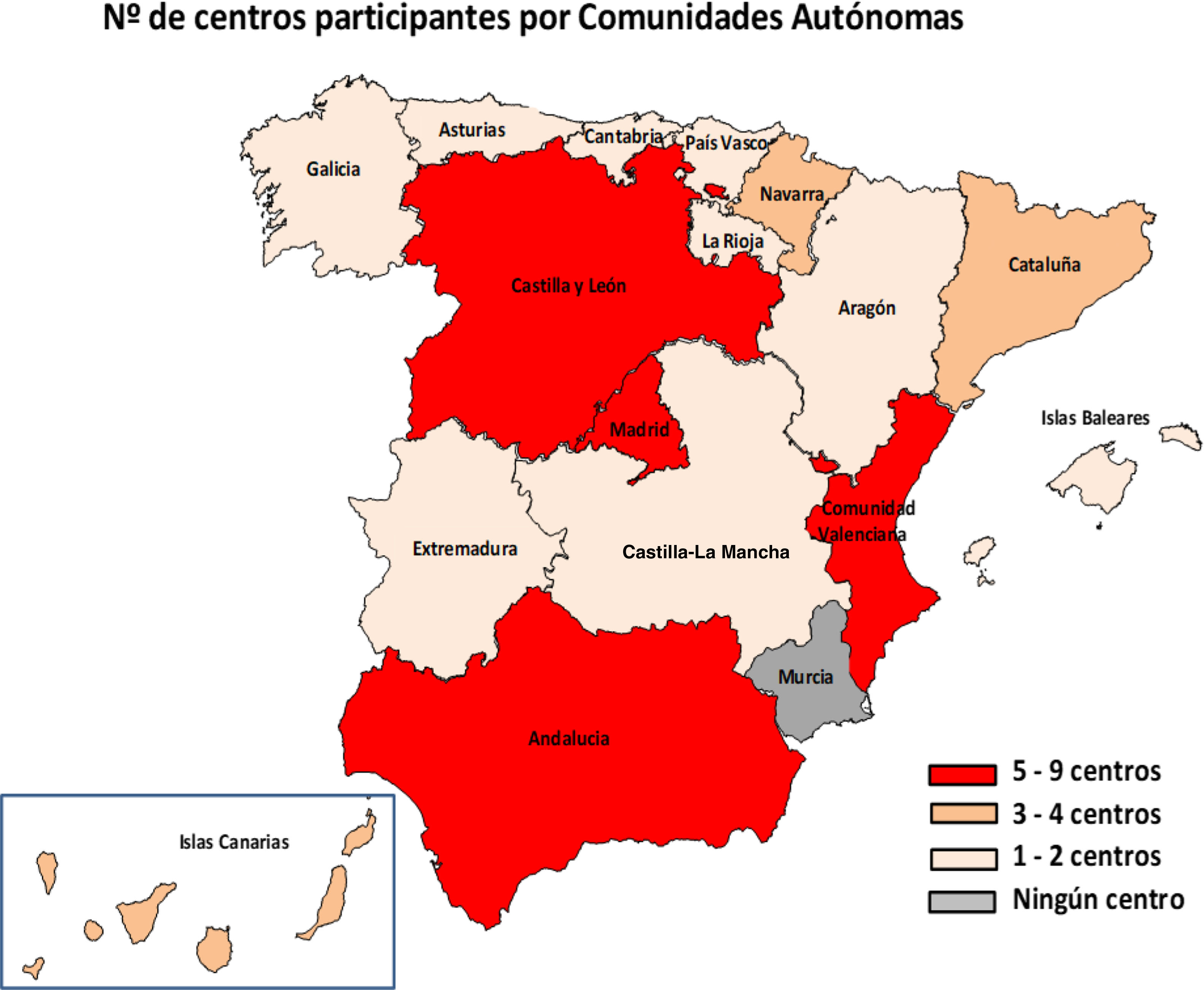

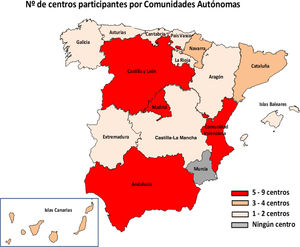

ResultsIn total, 51 centres (25.7%) from 29 provinces responded to the survey (Fig. 1). Of these centres, 46 were public, four were privately managed and one private; 48 served both adult and paediatric populations, two only adult and one only paediatric. Hp diagnostic methods were performed in their centre's microbiology laboratory in 94.1% (48/51) of cases and the remaining three sent the samples to other centres.

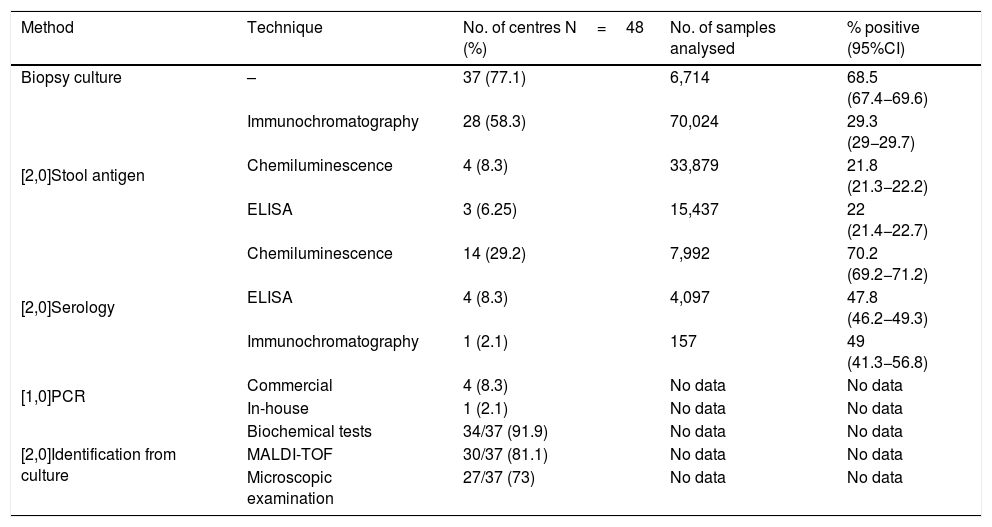

The most common diagnostic method used was gastric biopsy culture (77%, 37/48), followed by stool Ag detection (72.9%, 35/48), serology (39.6%, 19/48) and gastric biopsy PCR (10.4%, 5/48). Tables 1 and 2 show the different techniques used, the number of centres that perform each technique, the number of samples analysed and the positivity rate of each technique in 2016.

Methods and techniques used for the diagnosis of Hp and positivity rates in 2016.

| Method | Technique | No. of centres N=48 (%) | No. of samples analysed | % positive (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsy culture | – | 37 (77.1) | 6,714 | 68.5 (67.4−69.6) |

| [2,0]Stool antigen | Immunochromatography | 28 (58.3) | 70,024 | 29.3 (29−29.7) |

| Chemiluminescence | 4 (8.3) | 33,879 | 21.8 (21.3−22.2) | |

| ELISA | 3 (6.25) | 15,437 | 22 (21.4−22.7) | |

| [2,0]Serology | Chemiluminescence | 14 (29.2) | 7,992 | 70.2 (69.2−71.2) |

| ELISA | 4 (8.3) | 4,097 | 47.8 (46.2−49.3) | |

| Immunochromatography | 1 (2.1) | 157 | 49 (41.3−56.8) | |

| [1,0]PCR | Commercial | 4 (8.3) | No data | No data |

| In-house | 1 (2.1) | No data | No data | |

| [2,0]Identification from culture | Biochemical tests | 34/37 (91.9) | No data | No data |

| MALDI-TOF | 30/37 (81.1) | No data | No data | |

| Microscopic examination | 27/37 (73) | No data | No data |

Methods used for the diagnosis of Hp and positivity rates in 2016 according to number of samples analysed.

| Method (Total No. of samples) | No. of samples processed in 2016 | No. of centres | % positive (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1,0]Serology (12,222) | ≤ 100 | 5 | 54.9 (47.9−61.2) |

| > 100 | 14 | 64.2 (63.4−65.1) | |

| [2,0]Stool antigen (119,340)a | < 100 | 2 | 13.5 (7.5−24.2) |

| 100−500 | 9 | 22.2 (20.7−23.9) | |

| > 500 | 23 | 26.3 (26.1−26.6) | |

| [2,0]Culture (6,714) | < 10 | 7 | 12.5 (3.3−30.4) |

| 10−30 | 14 | 46.8 (40.1−53.4) | |

| > 30 | 16 | 70 (68.3−70.5) |

Nineteen laboratories performed Hp serology and all of them used at least one other diagnostic method apart from serology. The most widely used serological technique was chemiluminescence (14/19), followed by ELISA (4/19) and immunochromatography (1/19).

Stool antigenThirty-five laboratories carried out stool Ag detection, with immunochromatography being the most used technique (28/35), followed by chemiluminescence (4/35) and ELISA (3/35). For six laboratories, stool Ag detection was the only diagnostic method used, although three of them sent gastric biopsies to another centre for culture.

Gastric biopsy PCROnly five laboratories carried out PCR for Hp and all of them used at least one other diagnostic method; four of these five used a commercial PCR and only one used an in-house PCR.

Gastric biopsy cultureThirty-seven of the 48 laboratories performed gastric biopsy cultures, making this method the most widely used. Of these 37, 14 (37.8%) indicated that culture was performed only after treatment failure. In terms of the culture media used, 73% (27/37) used a commercial selective medium for Hp; 70.4% (19/27) accompanied the selective medium with blood agar and/or chocolate agar. To make identifications from culture, the majority (91.9%, 34/37) used biochemical tests (urease and catalase) and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (81.1%, 30/37), while 73% (27/37) also performed microscopic examination, with Gram stain being the most used across the laboratories (70.4%, 19/27). Other stains used were Gram-stain modified with fuchsin (5/27), giemsa (1/27), fuchsin (1/27) and acridine orange (1/27).

Urea breath testOf the 51 laboratories that responded to the survey, 82.3% (42/51) stated that their centres performed urea breath tests; four responded that they did not know if they did this test.

Urease test on biopsy58.82% (30/51) of the laboratories stated that the gastroenterologists at their centre performed the urease test on biopsy specimens; 13 answered that they did not know if it was done.

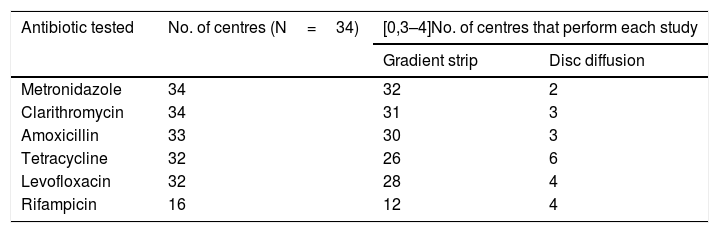

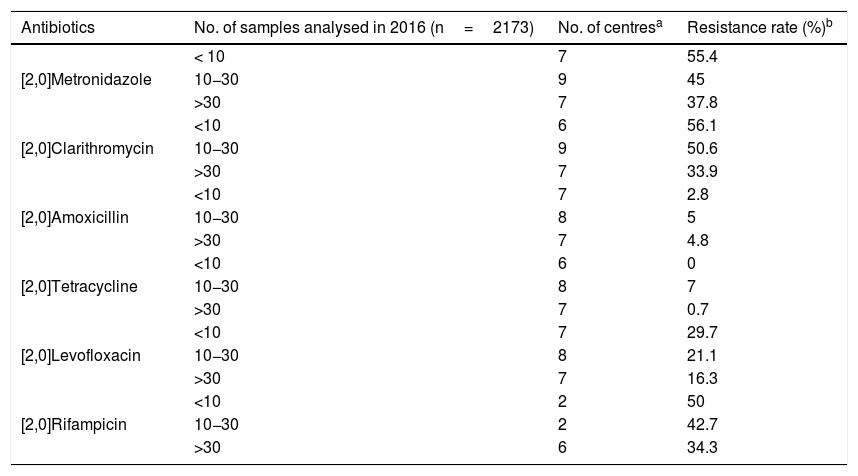

Sensitivity to antibioticsOf the 37 laboratories that performed gastric biopsy cultures, 34 performed antibiotic sensitivity tests; 32.5% (11/34) stated that these tests were only performed in patients with treatment failure and 29.4% (10/34) that they were performed in both treatment naive and previously treated patients. The rest answered that they did not have these data on the patients. The antibiotics studied and the method used are shown in Table 3. As cut-off points, 64.7% (22/34) used the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) criteria, 8.8% (3/34) those of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and 23.5% (8/34) both (EUCAST+CLSI). The antibiotic resistance data is shown in Table 4. Both metronidazole and clarithromycin had high rates of resistance, in some cases close to 50%. There was also significant resistance to rifampicin (over 34%) and levofloxacin (close to 20%). In contrast, amoxicillin and tetracycline have low rates of resistance.

Number of laboratories that tested each antibiotic and method used.

| Antibiotic tested | No. of centres (N=34) | [0,3–4]No. of centres that perform each study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient strip | Disc diffusion | ||

| Metronidazole | 34 | 32 | 2 |

| Clarithromycin | 34 | 31 | 3 |

| Amoxicillin | 33 | 30 | 3 |

| Tetracycline | 32 | 26 | 6 |

| Levofloxacin | 32 | 28 | 4 |

| Rifampicin | 16 | 12 | 4 |

Antibiotic resistance according to the samples analysed in 2016.

| Antibiotics | No. of samples analysed in 2016 (n=2173) | No. of centresa | Resistance rate (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2,0]Metronidazole | < 10 | 7 | 55.4 |

| 10−30 | 9 | 45 | |

| >30 | 7 | 37.8 | |

| [2,0]Clarithromycin | <10 | 6 | 56.1 |

| 10−30 | 9 | 50.6 | |

| >30 | 7 | 33.9 | |

| [2,0]Amoxicillin | <10 | 7 | 2.8 |

| 10−30 | 8 | 5 | |

| >30 | 7 | 4.8 | |

| [2,0]Tetracycline | <10 | 6 | 0 |

| 10−30 | 8 | 7 | |

| >30 | 7 | 0.7 | |

| [2,0]Levofloxacin | <10 | 7 | 29.7 |

| 10−30 | 8 | 21.1 | |

| >30 | 7 | 16.3 | |

| [2,0]Rifampicin | <10 | 2 | 50 |

| 10−30 | 2 | 42.7 | |

| >30 | 6 | 34.3 |

This national survey has gathered information about the Hp diagnosis methods currently used in clinical microbiology services/laboratories in Spain and provided data on antibiotic resistance. The vast majority (94%) of the centres that responded to the survey used some type of method for diagnosing Hp. The remaining responders sent the samples to another centre for diagnosis.

The most widely used diagnostic method was culture of gastric mucosa biopsies, closely followed by stool Ag detection. For the culture, most used a selective medium for Hp. For the identification of Hp in culture, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry is now commonly used by a large number of centres. This is consistent with the widespread use of this technique in recent years in the field of bacteriological diagnosis.

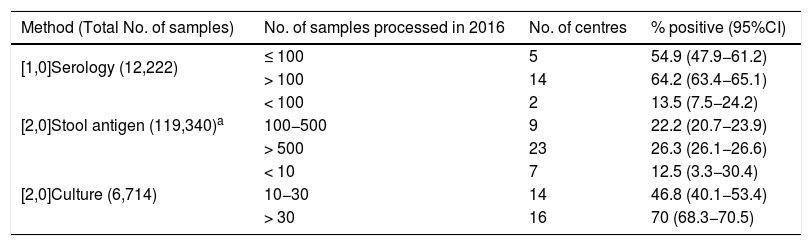

Although culture was the technique used in the most centres, a far larger number of samples were processed for stool Ag detection and serology, probably because they use a sample obtained by non-invasive methods. In all three methods the positivity rate increased with the number of samples processed. This was particularly striking in the case of culture (from 12.5% if fewer than 10 samples/year were processed to 70% where they processed more than 30 samples/year, P<.001). The most likely explanation is that for culture of Hp, experience in sample processing is a key factor in obtaining positive cultures.

Stool Ag detection was the most widely used non-invasive method and is becoming increasingly popular, largely due to the ease in obtaining the sample and the fact that, unlike serology, it not only serves for the initial diagnosis of infection but also to monitor response to treatment. Serology does not discriminate between past and active infection, as IgG antibodies can remain for years. Another advantage of the stool AG test over serology is that it has better sensitivity and specificity in the paediatric population. It also has advantages over the urea breath test as it is not necessary for the patient to attend for the test, they can simply hand the sample in. In the United Kingdom, in a national survey on the diagnosis of Hp similar to this one and carried out in 2016, the stool Ag test was the most common method, used by 94% of the centres.8 Gastric biopsy culture was performed in only 23.4% of the UK centres, a much lower rate than that obtained in our national survey. Of the techniques used for stool Ag detection in our study, immunochromatography was the most common (80% of the centres that perform stool Ag tests opted for this technique). It is the simplest, least laborious and quickest technique (takes approximately 15min) and this makes it much easier to implement in laboratories. However, it should be taken into account that the latest Maastricht V Consensus guidelines recommend the use of ELISA-based stool Ag tests and using monoclonal antibodies, and immunochromatography is not recommended.9 Recently published studies on stool Ag detection by immunochromatography, both in adults and in children, show very high sensitivity and specificity values of over 90%.10–13

For Hp serology testing, the most widely used method was chemiluminescence, currently the most common serological diagnostic technique. Thanks to the very high sensitivity of chemiluminescence and its low detection limit, this serology technique showed a higher positivity rate than ELISA and immunochromatography.14 The detection of anti-Hp antibodies in saliva or urine is not yet recommended by the guidelines, but in 2017 two studies were published with promising results.15,16 One of the studies even obtained higher sensitivity and specificity results for the detection of IgG in saliva than in serum.3 Despite these data, further studies are needed to confirm the results.

As far as Hp PCR is concerned, the low number of centres using this method may owe to its greater complexity and higher cost compared to other diagnostic methods. As an alternative to the use of gastric biopsies, studies have been published where they performed PCR on gastric juice, obtaining the same results with both samples,17 or using stool samples, with promising results.18

The urea breath test is used in most centres, but it is often performed by the clinical biochemistry services.

Practically all the centres that perform gastric biopsy cultures carry out antibiotic sensitivity tests. However, at some of these centres, the number of samples tested is very low (fewer than 10 samples/year). Antimicrobial gradient strips are the option most used by laboratories for the determination of antibiotic sensitivity. The resistance data provided by the centres show that clarithromycin and metronidazole have already arrived at an overall resistance rate close to 50%. These high resistance data are consistent with previous studies conducted in different countries.19–26 In a 2009 European multicentre study, the resistance rates for clarithromycin and metronidazole in adults in southern European countries (including Spain) were 21.5% and 29.7% respectively, highlighting how much resistance has increased over the last few years.27 These high levels of resistance have led to a decrease in the effectiveness of the "classic" triple therapy: proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole. Amongst the other antibiotics, there is also a high rate of resistance to rifampicin, close to 35%, and the rate for levofloxacin is now over 20% (in the 2009 multicentre study it was 13.1%).27 Resistance to tetracycline and amoxicillin, however, continues to be very low.

The high rates of resistance in Hp are now a cause of concern worldwide. In fact in 2017 the World Health Organisation included clarithromycin-resistant Hp on a list of pathogens with high priority for the research and development of new antibiotics.28 For all the antibiotics tested, the higher the number of samples, the lower the resistance rate. This could be because centres processing a larger number of samples may be dealing with samples from both previously treated and non-treated patients, and these treatment-naive patients are likely to have Hp strains with lower resistance rates than patients who had already tried other courses of antibiotics.

The major limitation of this study is that only 25.7% of the centres responded to the survey. It is very likely that the majority of the non-responding centres do not perform Hp diagnoses, and hence their lack of response. Moreover, some centres that did respond did not provide data for resistance or samples analysed. Another limitation is that the questionnaire was only sent to the heads of the microbiology services or units forming part of the analysis services and not to those in charge of gastroenterology or the clinical analysis services, and that has prevented us from obtaining a more accurate picture of how Hp is diagnosed in Spain. However, with almost all of Spain's autonomous regions represented, we consider that the number of responses was adequate and provided us with an understanding of the methods used by the microbiology services/laboratories. In terms of the antibiotic resistance data obtained, a very important limitation of the study is that it does not discriminate between the outcomes of treatment-naive or previously treated patients, so we are not able to calculate primary and secondary resistance rates. It would be a good idea to carry out studies differentiating the two groups of patients and comparing their resistance rates.

From the results obtained in this first national survey, we can state that the most widely used Hp diagnostic technique in clinical microbiology services/laboratories in Spain was the gastric biopsy culture, although stool Ag detection by immunochromatography was used in a larger number of samples. In terms of the antibiotic resistance data, the increase in Hp resistance to "first-line" antibiotics is worrying, and requires greater surveillance and more studies on this issue in the future.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they had no source of funding for the preparation of this document and nor do they have any conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC) [Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology] Grupo de Estudio para la Gestión en Microbiología Clínica (GEGMIC) [Study Group for Management in Clinical Microbiology] for sending the survey to the different laboratories.

Andalucía: Ana Isabel Suárez Barrenechea - Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla; María Andrades Ortega - Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla; Julio Vargas Romero – Hospital de Valme, Sevilla; Ignacio Correa Gómez - Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba; Ana Correa Ruiz - Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol, Málaga; Juan Carlos Alados Arboledas - Hospital Universitario de Jerez; Julio Vargas Romero - Hospital de Valme, Sevilla; Federico García García - Hospital Universitario San Cecilio, Granada; Francisco Franco Álvarez de Luna - Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva. Aragón: Carmen Aspíroz Sancho -Hospital Royo Villanova, Zaragoza; Ma Pilar Chocarro Escanero - Hospital Obispo Polanco, Teruel; Principado de Asturias: Julio DíazGigante - Hospital del Oriente de Asturias. Islas Baleares: Ana Mena Ribas - Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Mallorca; Ma Paz Díaz Antolín - Hospital Son Llatzer, Mallorca. Canarias: Laura Sante Fernández - Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife; Pino del Carmen Suárez Bordón - Hospital General de Fuerteventura; Ana Bordes Benítez - Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas. Cantabria: Jorge Calvo Montes - Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander. Castilla y León: Miguel Ángel Bratos Pérez - Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid; Ma Antonia García Castro - Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Palencia; Gregoria Megías Lobón - Hospital Universitario de Burgos; Raquel Elisa Rodríguez Tarazona y Noelia Arenal Andrés - Hospital Santos Reyes de Aranda del Duero, Burgos; Isabel Fernández Natal – Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León. Castilla-La Mancha: Ma José Rodríguez Escudero - Hospital Virgen de La Luz, Cuenca; César Gómez Hernando - Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo. Cataluña: Goretti Sauca - Hospital de Mataró, Barcelona; Pepa Pérez Jové - Catlab (Parc Logístic de Salut), Barcelona; Francesc Marco Reverté - Hospital Clinic, Barcelona; Virginia Rodríguez Garrido – Hospital Vall d′Hebron, Barcelona. Comunidad Valenciana: Juan Carlos Rodríguez Díaz y Javier Coy Coy - Hospital General Universitario de Alicante; María Navarro Cots - Hospital Vega Baja, Alicante; Carmen Martínez Peinado - Hospital Marina Baixa de Villajoyosa, Alicante; Aurora Blasco Molla - Hospital General Universitario de Castellón; Javier Buesa Gómez - Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia. Extremadura: Pedro María Aguirre Bernat – Hospital Campo Arañuelo, Cáceres. Galicia: José Llovo Taboada – Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela; Patricia Álvarez García - Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra. Comunidad de Madrid: Ana Miqueleiz Zapatero, Claudio Alba Rubio, Diego Domingo García y Teresa Alarcón Cavero - Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid; Rafael Cantón Moreno y Elia Gómez García de la Pedrosa - Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid; Mercedes Alonso Sanz - Hospital Infantil Universitario Ni˜no Jesús, Madrid; Ma Ángeles Orellana Miguel - Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid; Alberto Delgado-Iribarren Ga-Campero – Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid; Esteban Aznar Cano - Laboratorio Central de Madrid (BRSalud); Ma Isabel Sánchez Romero - Hospital Universitario Puerta del Hierro, Madrid; Sagrario Reyes Pecharromán - Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Madrid; Ma Teresa Pérez Pomata - Hospital Universitario de Móstoles, Madrid. Comunidad Foral de Navarra: José Leiva León – Clínica Universidad de Navarra; Matilde Elía López - Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra; José Javier García Irure - Hospital Reina Sofía de Tudela, Navarra. País Vasco: Milagrosa Montes Ros - Hospital Universitario Donostia, San Sebastián; Silvia Hernáez Crespo - Hospital Universitario de Álava. La Rioja: Marta Lamata Subero - Fundación Hospital de Calahorra, La Rioja.

Appendix 1lists the members of the Helicobacter pylori Microbiological Diagnosis Working Group.

Please cite this article as: Miqueleiz-Zapatero A, Alba-Rubio C, Domingo-García D, Cantón R, Gómez-García de la Pedrosa E, Aznar-Cano E, et al. Primera encuesta nacional sobre el diagnóstico de la infección por Helicobacter pylori en los laboratorios de microbiología clínica en España. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:410–416.