Delusional parasitosis or Ekbom syndrome is a condition described mainly in the fields of psychiatry and dermatology, with a complex diagnostic and therapeutic approach. However, it is uncommon to assess patients with this disease in infectious disease units. The objective of this work is to describe the experience of three infectious diseases departments with respect to this entity.

MethodsA retrospective descriptive study of 20 patients diagnosed with delusional parasitosis in three Infectious Diseases Services was performed between 2003 and 2017.

ResultsThe median age of the patients was 54 years, with a female/male ratio of 1.5:1. In 9 patients, an endoparasitic delirium (mainly digestive) was described, in 5 an ectoparasitic form was described, and in the remaining 6, a mixed form was described. Fourteen patients presented some type of psychiatric disorder. Four patients had alcohol or drug abuse disorder. All patients had made consultations to other specialties with a median of three per patient (range 1–7). Ten patients received “empirical” antiparasitic treatment and 8 received some type of psychopharmaceutical treatment. The evolution was very variable: in 3 patients, the delusional parasitosis was resolved; in 9 patients, the clinical manifestations persisted, and the remaining patients were lost to follow-up.

ConclusionsEkbom syndrome is a common process in infectious diseases, presenting some differences with other series evaluated by dermatologists and psychiatrists. Management of this disease should promote a multidisciplinary approach to enable a joint treatment, thus optimizing patient management and therapeutic adherence.

La parasitosis delirante o síndrome de Ekbom es una afección descrita principalmente en los campos de la psiquiatría y la dermatología, con un enfoque diagnóstico y terapéutico complejo. Sin embargo, es poco frecuente evaluar a los pacientes con esta enfermedad en unidades de enfermedades infecciosas. El objetivo de este trabajo es describir la experiencia de 3 departamentos de enfermedades infecciosas con respecto a esta entidad.

MétodosEntre 2003 y 2017 se llevó a cabo un estudio descriptivo retrospectivo de 20 pacientes a los que se les diagnosticó parasitosis delirante en 3 servicios de enfermedades infecciosas.

ResultadosLa mediana de edad de los pacientes era de 54 años, con una proporción mujeres/varones de 1,5:1. En 9 pacientes se describió un delirio endoparasitario (principalmente digestivo), en 5 se describió una forma ectoparasitaria y en los 6 restantes una forma mixta. Catorce pacientes presentaban algún tipo de trastorno psiquiátrico. Cuatro pacientes presentaban un trastorno de alcoholismo o drogadicción. Todos los pacientes habían acudido a consultas de otras especialidades con una mediana de 3 por paciente (intervalo de 1-7). Diez pacientes recibieron tratamiento antiparasitario «empírico» y 8 recibieron algún tipo de psicofármaco. La evolución fue muy variable: en 3 pacientes se resolvió la parasitosis delirante; en 9 pacientes persistieron las manifestaciones clínicas y se perdió el seguimiento de los demás pacientes.

ConclusionesEl síndrome de Ekbom es un proceso habitual en las enfermedades infecciosas, que presenta algunas diferencias con otras series evaluadas por dermatólogos y psiquiatras. El tratamiento de esta enfermedad debe promover un enfoque multidisciplinario que permita un tratamiento conjunto, optimizando así el tratamiento del paciente y el cumplimiento terapéutico.

Delusional parasitosis (DP) or Ekbom syndrome is a monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis characterized by the continued and erroneous feeling that your body is infected by living beings (insects, parasites) or inanimate objects (fibres or hairs).1,2 This last situation has been called Morgellons syndrome and has been the subject of multiple pseudoscientific publications.3 However, except in the delirious topic, these patients present, in other cognitive areas, intact mental functions and normal behaviour.4

This entity has received multiple historical names, such as acarophobia, entomophobia, parasitic delirium or dermatozoic delirium, although the name of Ekbom syndrome is preferred, which, by avoiding stigmatization of the patient, is better accepted.4,5 In this sense, it should not be confused with Willis-Ekbom syndrome, which corresponds to restless legs syndrome.6

DP is a very disabling process, both for the person affected and for their environment, which alters their quality of life and limits their professional activity. In addition, it is a syndrome that presents important therapeutic limitations, as will be indicated later.

The disease can be classified as primary when there is no underlying cause and secondary disease due to other psychiatric or organic diseases (neurological, toxic, pharmacological, endocrinological, neoplastic or deficit).6 Another classification used includes the “ectoparasitic” forms when it adheres to the skin and “endoparasitic” if it affects internal organs or natural orifices.6

The real incidence of DP is poorly understood due to several complementary factors: (i) the definitions have varied over time (DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-5 and ICD-10)7; (ii) the method of data collection (e.g., isolated cases, case series, surveys, reviews, meta-analyses)1,2,5,8–11; and (iii) scope of study (psychiatry, dermatology, internal medicine, infectious diseases, tropical medicine); patients often consult several specialties.2,5,12 In any case, the incidence and prevalence of DP has increased over the years.

In Spain, data on the incidence and characteristics of DP are scarce.13 Therefore, the objective of this paper is to describe the experience of this disease from the perspective of three infectious disease units.

Materials and methodsStudy settingA descriptive longitudinal retrospective study was designed with patients with DP according to DMS-5. Patients were selected for this study from three internal medicine practices specializing in infectious and tropical diseases: (i) the Unit of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine of the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular-Materno Infantil de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain (CHUIMIGC) and the Tropical Medicine Consultation of the Infectious Diseases Section of the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain (CAUSA), between 2003 and 2017 and (ii) the Unit of Infectious Diseases of the Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó, Elche, Spain (HUV), between 2010, when the Unit of Infectious of the Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó was created, and 2017. An active search of cases was carried out in the databases of the infectious units. Patients were referred from primary care and other hospital services because imported diseases were suspected. The criteria for inclusion were as follows: (1) age more than 18 years and (2) fixed conviction of infestation despite contrary evidence. Cases with a “diagnosis” of parasitosis were included, when they fulfilled the following criteria: (i) they presented an incompatible clinical picture of parasitosis, (ii) the serological diagnosis was not validated and (iii) after treatment with adequate drugs they did not present an adequate clinical and analytical response. The criteria for exclusion were as follows: (1) missing data and (2) Compatible clinical diagnosis with parasitosis and response after effective treatments. Biases were common of a retrospective study.

VariablesIn each patient, various demographic, epidemiological, clinical and evolutionary data were collected when available; specifically, the age and sex of the patients, the origin (autochthonous or immigrant) and the place of residence were evaluated. In addition, epidemiological data (travel history), relevant medical and psychiatric history, reason for consultation and description of symptoms by the patient as well as a detailed physical examination were evaluated. A complementary study was carried out that included blood count, ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate), basic biochemical study (glycaemia, urea and creatinine, liver tests, systematic and urinary sediment), TSH, serology of prevalent infections (HIV, HBV, HCV, Treponema pallidum) and coproparasitic study. Depending on the clinical manifestations, other complementary studies were included (e.g., image, serology, skin biopsy) as well as the study of the samples provided by the patients. On the other hand, we evaluated the number and type of specialists previously consulted (except primary care and emergency), the use of antiparasitic drugs and psychotropic drugs, and the evolution of patients. The “matchbox sign” refers to the physical presentation of the foreign material in a box. The “specimen sign” indicates the photographed or video material contributed or taught by the patient. Folie à deux, or shared delusional disorder is defined as psychiatric syndrome in which symptoms of a delusional belief and sometimes hallucinations are transmitted from one individual to another. The same syndrome shared by more than two people may be called folie à trois, folie à quatre, folie en famille “family madness”, or even folie à plusieurs “madness of several”.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis includes a descriptive analysis of each variable. Quantitative results are expressed as the median and interquartilic interval (IQ). The qualitative results are expressed in absolute and relative (percentage) values. The statistical package used was SPSS 23.0.

Ethics statementThe study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca (Salamanca, Spain). All data analysed were anonymized. Exemption of informed consent was obtained from the Ethics Committee due to the retrospective nature of the study and the anonymized data of patients. The procedures described here were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards described in the revised Declaration of Helsinki in 2013.

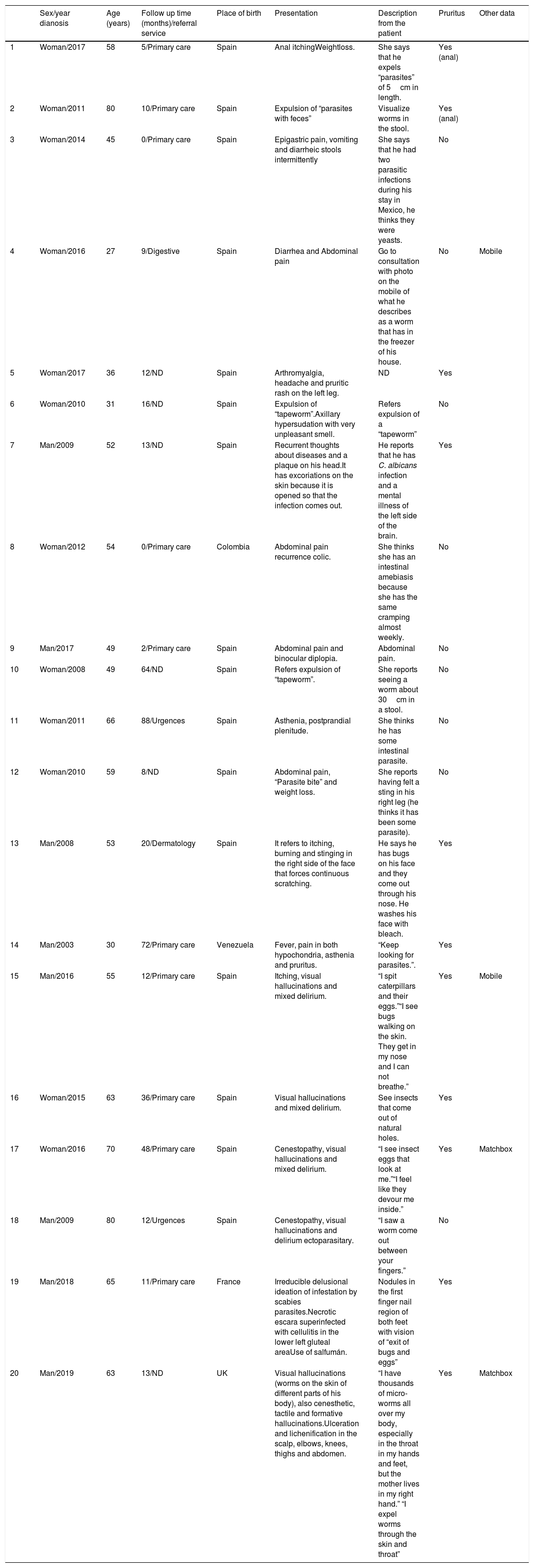

ResultsTwenty patients were evaluated throughout the study period. Tables 1 and 2 show the detailed data. The median age of the patients was 54 years (range: 27-80), with a female/male ratio of 1.5:1 (12/8). Of these, 19% (4/21) were foreigners (2 Latin Americans and 2 Europeans).

Main epidemiological and clinical features of patients.

| Sex/year dianosis | Age (years) | Follow up time (months)/referral service | Place of birth | Presentation | Description from the patient | Pruritus | Other data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Woman/2017 | 58 | 5/Primary care | Spain | Anal itchingWeightloss. | She says that he expels “parasites” of 5cm in length. | Yes (anal) | |

| 2 | Woman/2011 | 80 | 10/Primary care | Spain | Expulsion of “parasites with feces” | Visualize worms in the stool. | Yes (anal) | |

| 3 | Woman/2014 | 45 | 0/Primary care | Spain | Epigastric pain, vomiting and diarrheic stools intermittently | She says that he had two parasitic infections during his stay in Mexico, he thinks they were yeasts. | No | |

| 4 | Woman/2016 | 27 | 9/Digestive | Spain | Diarrhea and Abdominal pain | Go to consultation with photo on the mobile of what he describes as a worm that has in the freezer of his house. | No | Mobile |

| 5 | Woman/2017 | 36 | 12/ND | Spain | Arthromyalgia, headache and pruritic rash on the left leg. | ND | Yes | |

| 6 | Woman/2010 | 31 | 16/ND | Spain | Expulsion of “tapeworm”.Axillary hypersudation with very unpleasant smell. | Refers expulsion of a “tapeworm” | No | |

| 7 | Man/2009 | 52 | 13/ND | Spain | Recurrent thoughts about diseases and a plaque on his head.It has excoriations on the skin because it is opened so that the infection comes out. | He reports that he has C. albicans infection and a mental illness of the left side of the brain. | Yes | |

| 8 | Woman/2012 | 54 | 0/Primary care | Colombia | Abdominal pain recurrence colic. | She thinks she has an intestinal amebiasis because she has the same cramping almost weekly. | No | |

| 9 | Man/2017 | 49 | 2/Primary care | Spain | Abdominal pain and binocular diplopia. | Abdominal pain. | No | |

| 10 | Woman/2008 | 49 | 64/ND | Spain | Refers expulsion of “tapeworm”. | She reports seeing a worm about 30cm in a stool. | No | |

| 11 | Woman/2011 | 66 | 88/Urgences | Spain | Asthenia, postprandial plenitude. | She thinks he has some intestinal parasite. | No | |

| 12 | Woman/2010 | 59 | 8/ND | Spain | Abdominal pain, “Parasite bite” and weight loss. | She reports having felt a sting in his right leg (he thinks it has been some parasite). | No | |

| 13 | Man/2008 | 53 | 20/Dermatology | Spain | It refers to itching, burning and stinging in the right side of the face that forces continuous scratching. | He says he has bugs on his face and they come out through his nose. He washes his face with bleach. | Yes | |

| 14 | Man/2003 | 30 | 72/Primary care | Venezuela | Fever, pain in both hypochondria, asthenia and pruritus. | “Keep looking for parasites.”. | Yes | |

| 15 | Man/2016 | 55 | 12/Primary care | Spain | Itching, visual hallucinations and mixed delirium. | “I spit caterpillars and their eggs.”“I see bugs walking on the skin. They get in my nose and I can not breathe.” | Yes | Mobile |

| 16 | Woman/2015 | 63 | 36/Primary care | Spain | Visual hallucinations and mixed delirium. | See insects that come out of natural holes. | Yes | |

| 17 | Woman/2016 | 70 | 48/Primary care | Spain | Cenestopathy, visual hallucinations and mixed delirium. | “I see insect eggs that look at me.”“I feel like they devour me inside.” | Yes | Matchbox |

| 18 | Man/2009 | 80 | 12/Urgences | Spain | Cenestopathy, visual hallucinations and delirium ectoparasitary. | “I saw a worm come out between your fingers.” | No | |

| 19 | Man/2018 | 65 | 11/Primary care | France | Irreducible delusional ideation of infestation by scabies parasites.Necrotic escara superinfected with cellulitis in the lower left gluteal areaUse of salfumán. | Nodules in the first finger nail region of both feet with vision of “exit of bugs and eggs” | Yes | |

| 20 | Man/2019 | 63 | 13/ND | UK | Visual hallucinations (worms on the skin of different parts of his body), also cenesthetic, tactile and formative hallucinations.Ulceration and lichenification in the scalp, elbows, knees, thighs and abdomen. | “I have thousands of micro-worms all over my body, especially in the throat in my hands and feet, but the mother lives in my right hand.” “I expel worms through the skin and throat” | Yes | Matchbox |

ND: no data.

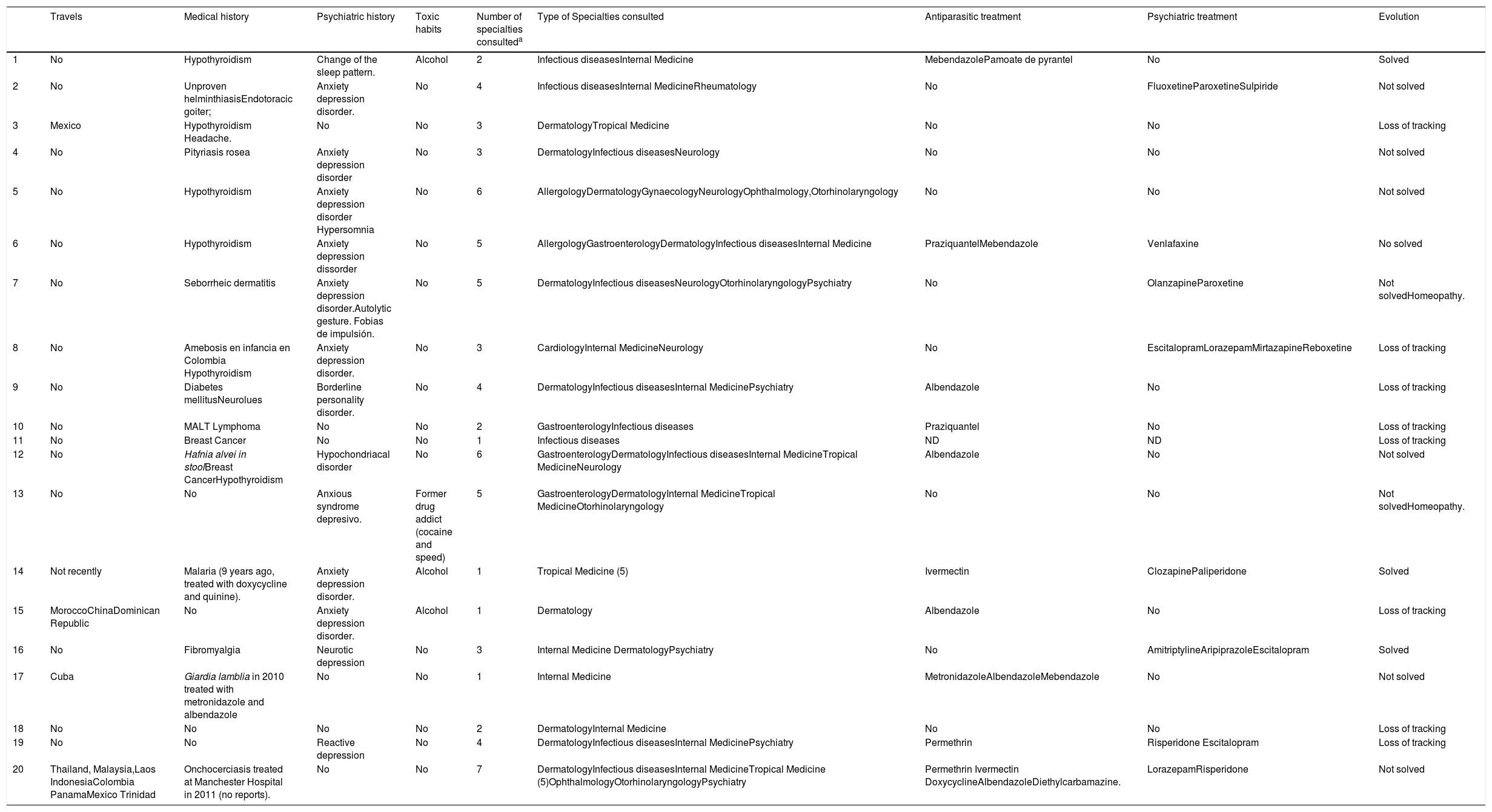

Medical records and treatment of patients.

| Travels | Medical history | Psychiatric history | Toxic habits | Number of specialties consulteda | Type of Specialties consulted | Antiparasitic treatment | Psychiatric treatment | Evolution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | Hypothyroidism | Change of the sleep pattern. | Alcohol | 2 | Infectious diseasesInternal Medicine | MebendazolePamoate de pyrantel | No | Solved |

| 2 | No | Unproven helminthiasisEndotoracic goiter; | Anxiety depression disorder. | No | 4 | Infectious diseasesInternal MedicineRheumatology | No | FluoxetineParoxetineSulpiride | Not solved |

| 3 | Mexico | Hypothyroidism Headache. | No | No | 3 | DermatologyTropical Medicine | No | No | Loss of tracking |

| 4 | No | Pityriasis rosea | Anxiety depression disorder | No | 3 | DermatologyInfectious diseasesNeurology | No | No | Not solved |

| 5 | No | Hypothyroidism | Anxiety depression disorder Hypersomnia | No | 6 | AllergologyDermatologyGynaecologyNeurologyOphthalmology,Otorhinolaryngology | No | No | Not solved |

| 6 | No | Hypothyroidism | Anxiety depression dissorder | No | 5 | AllergologyGastroenterologyDermatologyInfectious diseasesInternal Medicine | PraziquantelMebendazole | Venlafaxine | No solved |

| 7 | No | Seborrheic dermatitis | Anxiety depression disorder.Autolytic gesture. Fobias de impulsión. | No | 5 | DermatologyInfectious diseasesNeurologyOtorhinolaryngologyPsychiatry | No | OlanzapineParoxetine | Not solvedHomeopathy. |

| 8 | No | Amebosis en infancia en Colombia Hypothyroidism | Anxiety depression disorder. | No | 3 | CardiologyInternal MedicineNeurology | No | EscitalopramLorazepamMirtazapineReboxetine | Loss of tracking |

| 9 | No | Diabetes mellitusNeurolues | Borderline personality disorder. | No | 4 | DermatologyInfectious diseasesInternal MedicinePsychiatry | Albendazole | No | Loss of tracking |

| 10 | No | MALT Lymphoma | No | No | 2 | GastroenterologyInfectious diseases | Praziquantel | No | Loss of tracking |

| 11 | No | Breast Cancer | No | No | 1 | Infectious diseases | ND | ND | Loss of tracking |

| 12 | No | Hafnia alvei in stoolBreast CancerHypothyroidism | Hypochondriacal disorder | No | 6 | GastroenterologyDermatologyInfectious diseasesInternal MedicineTropical MedicineNeurology | Albendazole | No | Not solved |

| 13 | No | No | Anxious syndrome depresivo. | Former drug addict (cocaine and speed) | 5 | GastroenterologyDermatologyInternal MedicineTropical MedicineOtorhinolaryngology | No | No | Not solvedHomeopathy. |

| 14 | Not recently | Malaria (9 years ago, treated with doxycycline and quinine). | Anxiety depression disorder. | Alcohol | 1 | Tropical Medicine (5) | Ivermectin | ClozapinePaliperidone | Solved |

| 15 | MoroccoChinaDominican Republic | No | Anxiety depression disorder. | Alcohol | 1 | Dermatology | Albendazole | No | Loss of tracking |

| 16 | No | Fibromyalgia | Neurotic depression | No | 3 | Internal Medicine DermatologyPsychiatry | No | AmitriptylineAripiprazoleEscitalopram | Solved |

| 17 | Cuba | Giardia lamblia in 2010 treated with metronidazole and albendazole | No | No | 1 | Internal Medicine | MetronidazoleAlbendazoleMebendazole | No | Not solved |

| 18 | No | No | No | No | 2 | DermatologyInternal Medicine | No | No | Loss of tracking |

| 19 | No | No | Reactive depression | No | 4 | DermatologyInfectious diseasesInternal MedicinePsychiatry | Permethrin | Risperidone Escitalopram | Loss of tracking |

| 20 | Thailand, Malaysia,Laos IndonesiaColombia PanamaMexico Trinidad | Onchocerciasis treated at Manchester Hospital in 2011 (no reports). | No | No | 7 | DermatologyInfectious diseasesInternal MedicineTropical Medicine (5)OphthalmologyOtorhinolaryngologyPsychiatry | Permethrin Ivermectin DoxycyclineAlbendazoleDiethylcarbamazine. | LorazepamRisperidone | Not solved |

ND: no data.

In 9 patients, an endoparasitic delirium (mainly digestive) was described, in 5, an ectoparasitic form was described, and in the remaining 6, a mixed form was described. The time of symptomatology evolution was difficult to establish in several cases, although it oscillated between 2 months and 10 years. The presence of pruritus, generalized or localized (anal) was explicitly recorded in 11 patients. Two patients presented the “matchbox sign”, and two others presented the “specimen sign”. Only in one case was “folie a deux” observed (patient # 16).

There was a history of travel to less developed countries in 4 patients. Among the relevant pathological history, seven had thyroid alterations (6 cases of hypothyroidism), three had neoplasms (breast and lymphoma), and five had previous parasitoses (although undocumented in most of them). Fourteen presented some type of psychiatric disorder, the most frequent being anxiety-depressive syndrome. With regard to toxic habits, three patients (14.3%) had alcohol abuse disorder, and one patient (4.8%) was a former cocaine and deoxiefedrine (speed) user.

The complementary examinations did not show relevant alterations except in two patients: an infestation by Sarcoptes scabiei (case 7) and an infection by Strongyloides stercoralis (case 9). In two patients, antibodies against Leishmania spp and Fasciola spp were detected, without any apparent relationship with the clinical manifestations of the patient.

In addition to the consultation to emergency services and primary care, before the evaluation by our units, all had made consultations to other specialties with a median of three per patient (range 1–7). Ten patients received “empirical” antiparasitic treatment at some point in their evolution, and 8 received some type of psychotropic drug. The evolution was very variable: in three patients, the DP was resolved; in nine patients, the clinical manifestations persisted, and in the rest, the patients did not attend the programmed follow-up.

DiscussionThe incidence of delusional parasitosis is very variable, ranging from 0.2 to 23.6 per 100,000 inhabitants/year in published series. Practically all of the series published come from dermatology and/or psychiatry services, and there was no bibliographic review of data about patients with DP assessed by infectious diseases or internal medicine services.9,14,15 In general, DP is more frequent in Caucasians, elderly (50–60 years) and, in most series, has a predominance in females (ranging between 1.4:1 and 3:1).1,2,5,14,16–18 Patients included in our series have an age similar to that reported in the literature (54 years), although the female/male ratio is at the lower limit (1.5:1). There is an association between older age and female sex, attributed to neurological and skin changes,5 while the male sex has been associated with a younger age, mainly in relation to the consumption of toxins,19 an aspect not shown in this series.

DP is a syndrome of prolonged evolution. In our series, the interval between the appearance of the symptomatology and the evaluation was very variable, according to that indicated in the literature.5,11,18 Unlike other series, the main manifestations were “endoparasitic” (associated or not to “ectoparasitic”), which is different than the rest of the series mentioned, in which skin manifestations predominate. In the DP, a classic characteristic called the “matchbox sign” has been described, which consists of the contribution by the patient of some container in which they claim to contain the parasite.1 This behaviour is present in 10% of the patients in our series and are clearly lower than those described by other authors.17,18 More frequent is the so-called “specimen sign”, in which the patient provides some “proof” of the infestation, currently through photographs or videos obtained by mobile telephone.18,20

In practically all patients, DP coexisted with medical, psychiatric and/or toxic drug history. The medical history highlights include hypothyroidism (30%), and the psychiatric highlights include anxiety-depressive syndrome (40%). However, the consumption of toxins (alcohol or drugs) is much less frequent than in other series, although there may be a negative bias due to not having included a specific determination in all patients.

An important aspect, which is less evaluated in other series of DP, is the need to carry out a complete parasitological study. In five patients, there was a history of parasitosis (although undocumented in many cases), in two of them a positive serology result was obtained, and in two others, an authentic parasitosis was discovered. In addition to the possibility of an etiological treatment, the previous parasitosis, in many cases related to the origin of the patient or the history of travel, may be related to the trigger of DP.21

DP has an important personal, labour, family and health repercussions. In the different studies, social isolation and anxious depressive and substance abuse disorders are described as the most determining premorbid factors of patients suffering from this disease.1 On the other hand, in a large series, one-third of patients were unemployed or retired, with DP being the factor involved in this work situation.2 In a variable percentage of cases (8–49%), DP can be shared with other people, usually living together, depending on the number of people affected, which is known as “folie a deux”.17 In our series, we only observed it in one patient. Finally, DP is an important health problem since it involves a large number of consultations with different specialties, with the repetition of complementary examinations and the inappropriate and unnecessary use of antiparasitic drugs.12,18 In our series, the median of the specialties consulted (in addition to consultations in primary care and emergency services was 3 (range 1-7), and 50% received one or more antiparasitics.

The therapeutic approach of these patients is complex, motivated mainly by the high resistance of patients to recognize the psychiatric nature of the disorder, which makes its evaluation by these specialists difficult. Therefore, it is necessary that the management of patients be performed at least initially by internists or dermatologists. Several useful strategies have been described in this sense that include the use of an appropriate language, “pacts with the patient”, time control, use of topical drugs such as crotamiton with antipruritic and antiscabiotic action and even skin biopsies with “therapeutic” purpose.17,22,23 In any case, the treatment of choice are the antipsychotics that must be offered to the patient using the name of neuroleptics and emphasizing that they are prescribed for their antipruritic or sedative action.17,22 Currently, there is no evidence to recommend treatment above the others,24 so the recommendations that we can establish are based on the side effects of each of them. Antidepressants have, in general, a lower efficacy.25 Risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, pimozide and aripiprazole has been described as treatment options.26 Historically, Pimozide was the most used neuroleptic in DP. However, nowadays its use should be limited to the lack of response to atypical antipsychotics, since its benefits are not considered to outweigh its risks.27 Despite more investigation is required, Aripiprazole could be considered as one of the choices to the DP, thanks to its efficacy as an antipsychotic, its better cardio metabolic profile (unlike olanzapine and quetiapine) and less hyperprolactinemia and extrapyramidal effects risks (unlike risperidone). It is a partial agonist at D2 receptors, function that differs to other atypical antipsychotics mentioned above. Moreover, Aripiprazole could add some antidepressant effect (blocking the 5HT2c and 7 receptors and its partial agonist action on 5HT1A).27–29 The most used neuroleptic has been pimozide, although the extrapyramidal effects and cardiac alterations (QT prolongation) limit its use. Olanzapine has fewer extrapyramidal side effects but is associated with metabolic disorders (weight gain, cholesterol and triglycerides) that limit its use. Risperidone has less metabolic effects but can cause an elevation of prolactin. Therefore, the neuroleptic of choice at present is aripiprazole. In our series, only 5 patients were treated with effective neuroleptics. In any case, the evolution of patients was poor, with persistence of symptoms and loss of follow-up, which has been reported by other authors.30

The main limitations to this work are those of retrospective studies, such as the possible underdiagnosis of the disease, variability in practitioners and missing data. This may pose a selection and information bias on the results.

In summary, DP is an infrequent process in the infectious disease services, which presents some differences with other series evaluated by dermatologists and psychiatrists. Management is complex and often involves a large consumption of resources. Therefore, for the management of this disease, we should promote a multidisciplinary approach based on a fluid relationship between the different services involved to enable a joint approach, optimizing patient management and therapeutic adherence.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare no potential conflicts of interest and no sources of support.

None.