Limited therapeutic options and high mortality make the management of OXA-48-like carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPOXA-48) bacteraemia complicated. The aim of the study was to describe the clinical characteristics of KPOXA-48 bacteraemia between October 2013 and December 2016.

Material and methodsThe variables to analyse were retrospectively collected from medical records. Carbapenemase production was confirmed by phenotypic and molecular methods.

ResultsA total of 38 patients with bacteraemia were included, mainly classified as hospital-acquired (n=31). The majority of cases were secondary bacteraemia (n=26), most commonly arising from the urinary tract (n=11). All isolates presented a multidrug-resistant profile with the extended spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15 and the carbapenemase OXA-48-like production. The crude mortality rate with adequate targeted antibiotic therapy was 0%, rising to 55% with inadequate treatment (p=0.0015).

ConclusionsThis study highlights the importance of identifying this resistance mechanism, the patient factors, type of bacteraemia and adequacy of antibiotic therapy in the outcome of bacteraemia.

El manejo de las bacteriemias por Klebsiella pneumoniae productora de carbapenemasa del tipo OXA-48 (KPOXA-48) es complicado por las escasas opciones terapéuticas y la elevada mortalidad. El objetivo del estudio fue describir las características clínicas de bacteriemia por KPOXA-48 entre octubre de 2013 y diciembre de 2016.

Material y métodosSe recogieron retrospectivamente de las historias clínicas las variables para analizar. La producción de carbapenemasas se confirmó por métodos fenotípicos y moleculares.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 38 pacientes con bacteriemia, mayoritariamente de origen nosocomial (n=31). Un alto porcentaje de las bacteriemias (n=26) fueron secundarias, principalmente de origen urinario (n=11). Todos los aislamientos eran multirresistentes con producción de la beta-lactamasa de espectro extendido CTX-M-15 y carbapenemasa del tipo OXA-48. La mortalidad bruta con antibioterapia dirigida adecuada fue del 0% y la inadecuada del 55% (p=0,0015).

ConclusionesSe pone de manifiesto la importancia de identificar este mecanismo de resistencia, los factores del paciente, el tipo de bacteriemia y la adecuación de la estrategia terapéutica en la evolución clínica.

Though not very common, bacteraemia is a clinical entity associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 The problem of multidrug-resistant microorganisms has been added to this. Notable among them is the rapidly spreading carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae.2 At present, inter-regional spread is occurring in Spain, with a predominance of OXA-48 (KPOXA-48) and VIM carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae.3 These often acquire a profile of multidrug resistance4 and therefore are associated with high rates of treatment failure and mortality. These rates approach 50% in cases of bacteraemia.5

The objective of this paper is to report the clinical, epidemiological, microbiological and therapeutic characteristics as well as the gross intrahospital mortality of patients with KPOXA-48 bacteraemia diagnosed in a tertiary hospital.

Materials and methodsBackgroundThis retrospective study was conducted at the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias (Tenerife, Spain), in a tertiary hospital with a reference population of 446,253 inhabitants. Since the first KPOXA-48 outbreak in late 2013, intrahospital spread has been clonal. KPOXA-48 is now endemic. Since then, a surveillance programme4 consisting of rectal sampling has been applied in patients hospitalised in units with at least one positive case and systematically in intensive care unit admissions.

Study populationAll adult patients (>18 years of age) with bacteraemia due to KPOXA-48 were enrolled between October 2013 and December 2016 and the first episode of bacteraemia due to this same microorganism was considered. In addition, variables were collected from the patients’ medical histories to evaluate their influence on the patients’ clinical courses.

Bacteraemia was classified as nosocomial or community-acquired. Source of infection was defined according to the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control.6

Based on the current recommendations,7 adequate antibiotic treatment was defined as the use of two antibiotics active in vitro including a carbapenem with an MIC ≤8mg/l. Inadequate treatment was defined as the administration of a single antimicrobial or combination therapy when none or just one of the antimicrobials was active in vitro. Similarly, treatment was considered inadequate if the doses used were lower than those recommended based on the patient's kidney function.

Microbiological studySamples were processed using the BacT/ALERT® automatic blood culture analyser (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). Identification and antibiogram preparation were done with the VITEK-2® system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). Next, carbapenem susceptibility was confirmed using the gradient diffusion technique, and carbapenemase production was confirmed using the phenotypic method of discs and inhibitors. The susceptibility study was performed in accordance with the criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.8 Finally, the Centro Nacional de Microbiología [Spanish National Centre for Microbiology] (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid) detected carbapenemase and broad-spectrum β-lactamase genes using polymerase chain reaction.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were compared with the Mann–Whitney U method and categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, as applicable. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analysed with the SPSS 17.0 statistical program (IBM-SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, United States).

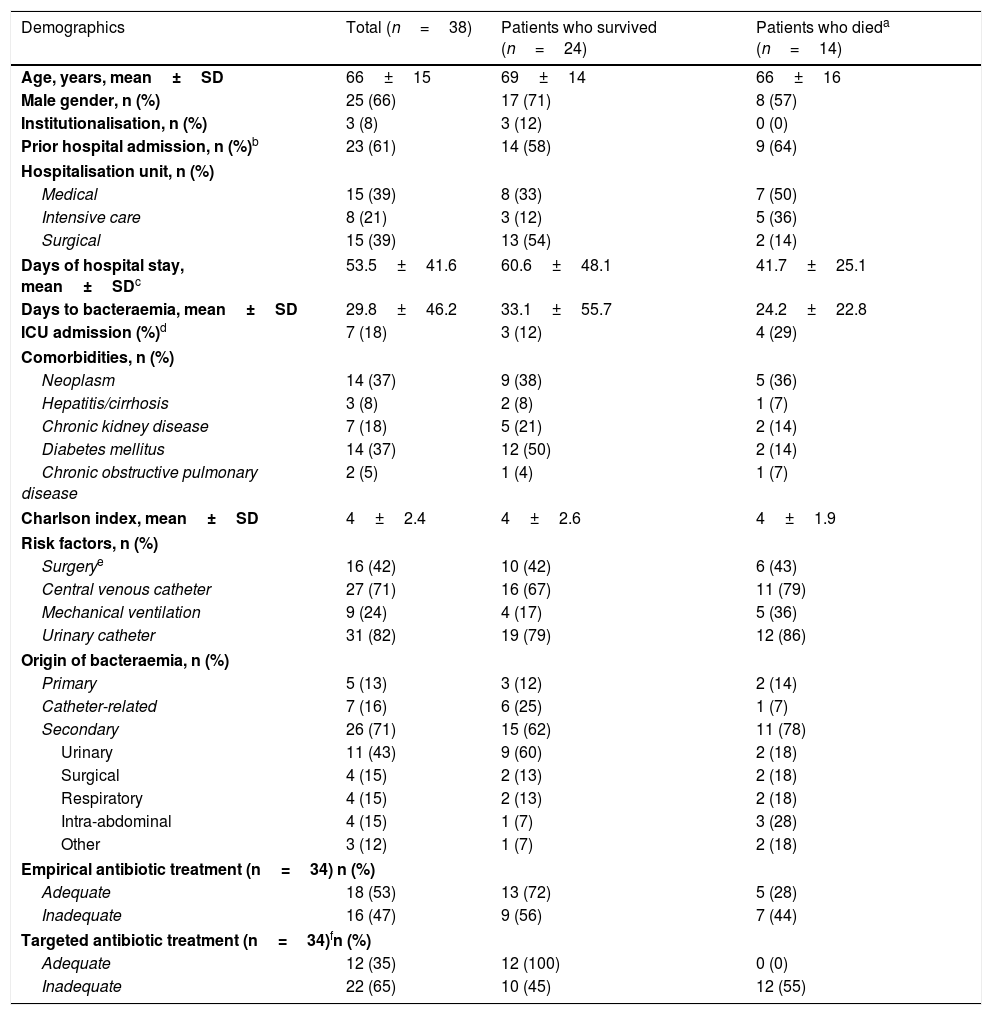

ResultsClinical and epidemiological characteristicsThe study enrolled 38 patients with a mean age of 66 years. Of these patients, 89% (34/38) had rectal colonisation by KPOXA-48. In addition, 68% (26/38) had at least one underlying disease. The patients had been admitted mainly to medical and surgical units when they were diagnosed with bacteraemia. Gross intrahospital mortality was 37%. The mean number of days between the first positive blood culture and the date of death was 18. Risk factors for developing bacteraemia included the use of devices such as a urinary catheter or a central venous catheter (Table 1).

Characteristics of patients with bacteraemia due to OXA-48-positive K. pneumoniae during hospitalisation.

| Demographics | Total (n=38) | Patients who survived (n=24) | Patients who dieda (n=14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean±SD | 66±15 | 69±14 | 66±16 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 25 (66) | 17 (71) | 8 (57) |

| Institutionalisation, n (%) | 3 (8) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Prior hospital admission, n (%)b | 23 (61) | 14 (58) | 9 (64) |

| Hospitalisation unit, n (%) | |||

| Medical | 15 (39) | 8 (33) | 7 (50) |

| Intensive care | 8 (21) | 3 (12) | 5 (36) |

| Surgical | 15 (39) | 13 (54) | 2 (14) |

| Days of hospital stay, mean±SDc | 53.5±41.6 | 60.6±48.1 | 41.7±25.1 |

| Days to bacteraemia, mean±SD | 29.8±46.2 | 33.1±55.7 | 24.2±22.8 |

| ICU admission (%)d | 7 (18) | 3 (12) | 4 (29) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Neoplasm | 14 (37) | 9 (38) | 5 (36) |

| Hepatitis/cirrhosis | 3 (8) | 2 (8) | 1 (7) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7 (18) | 5 (21) | 2 (14) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (37) | 12 (50) | 2 (14) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2 (5) | 1 (4) | 1 (7) |

| Charlson index, mean±SD | 4±2.4 | 4±2.6 | 4±1.9 |

| Risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Surgerye | 16 (42) | 10 (42) | 6 (43) |

| Central venous catheter | 27 (71) | 16 (67) | 11 (79) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 9 (24) | 4 (17) | 5 (36) |

| Urinary catheter | 31 (82) | 19 (79) | 12 (86) |

| Origin of bacteraemia, n (%) | |||

| Primary | 5 (13) | 3 (12) | 2 (14) |

| Catheter-related | 7 (16) | 6 (25) | 1 (7) |

| Secondary | 26 (71) | 15 (62) | 11 (78) |

| Urinary | 11 (43) | 9 (60) | 2 (18) |

| Surgical | 4 (15) | 2 (13) | 2 (18) |

| Respiratory | 4 (15) | 2 (13) | 2 (18) |

| Intra-abdominal | 4 (15) | 1 (7) | 3 (28) |

| Other | 3 (12) | 1 (7) | 2 (18) |

| Empirical antibiotic treatment (n=34) n (%) | |||

| Adequate | 18 (53) | 13 (72) | 5 (28) |

| Inadequate | 16 (47) | 9 (56) | 7 (44) |

| Targeted antibiotic treatment (n=34)fn (%) | |||

| Adequate | 12 (35) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Inadequate | 22 (65) | 10 (45) | 12 (55) |

p Value not significant for all comparisons, except for adequate vs inadequate targeted antibiotic treatment (p=0.0015).

Bacteraemia was mainly nosocomial (32/38; 84%), and secondary bacteraemia was mainly of urinary origin (11/38; 29%). All patients with community-acquired bacteraemia had been admitted in the past three months, two of which were institutionalised.

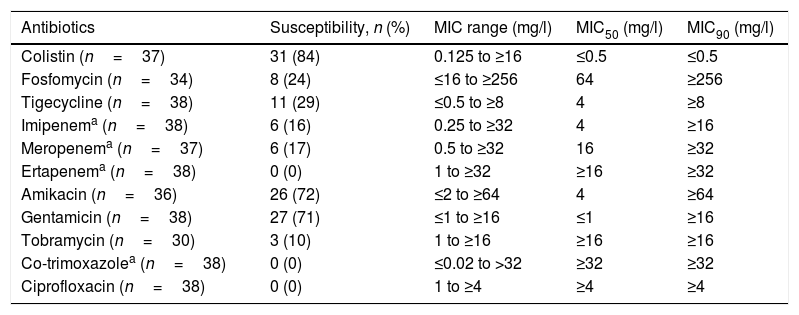

Microbiological characteristicsAll isolates were blaOXA-48 carbapenemase-producing and CTX-M-15 broad-spectrum β-lactamase-producing bacteria. All had a profile of multidrug resistance, with the exception of one, identified as pan-resistant.9 In general, the most active antibiotics were colistin, amikacin and gentamicin (Table 2). Against 30 isolates, the MIC of at least one carbapenem was ≤8mg/l: imipenem (n=28; 74%), meropenem (n=16; 44%) and ertapenem (n=7; 18%).

Antimicrobial susceptibility of OXA-48-positive K. pneumoniae isolates causing bacteraemia.

| Antibiotics | Susceptibility, n (%) | MIC range (mg/l) | MIC50 (mg/l) | MIC90 (mg/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colistin (n=37) | 31 (84) | 0.125 to ≥16 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 |

| Fosfomycin (n=34) | 8 (24) | ≤16 to ≥256 | 64 | ≥256 |

| Tigecycline (n=38) | 11 (29) | ≤0.5 to ≥8 | 4 | ≥8 |

| Imipenema (n=38) | 6 (16) | 0.25 to ≥32 | 4 | ≥16 |

| Meropenema (n=37) | 6 (17) | 0.5 to ≥32 | 16 | ≥32 |

| Ertapenema (n=38) | 0 (0) | 1 to ≥32 | ≥16 | ≥32 |

| Amikacin (n=36) | 26 (72) | ≤2 to ≥64 | 4 | ≥64 |

| Gentamicin (n=38) | 27 (71) | ≤1 to ≥16 | ≤1 | ≥16 |

| Tobramycin (n=30) | 3 (10) | 1 to ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 |

| Co-trimoxazolea (n=38) | 0 (0) | ≤0.02 to >32 | ≥32 | ≥32 |

| Ciprofloxacin (n=38) | 0 (0) | 1 to ≥4 | ≥4 | ≥4 |

In 53% of cases, empirical antibiotic treatment was adequate. Targeted antibiotic treatment was adequate in 35% of patients and inadequate in 65%. Intrahospital mortality was 55% (12/22) in the group of patients in which targeted antibiotic therapy had been inadequate; no patient died with adequate targeted treatment (0/12) (p=0.0015) (Table 1).

DiscussionThere are few studies on experience with KPOXA-48 bacteraemia. This study provides new data on the clinical, epidemiological, microbiological and therapeutic characteristics of KPOXA-48 bacteraemia in a hospital endemic context.

Overall mortality in infections due to carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae (CPE) is generally high.5,10 However, the mortality data published do vary. For example, in a Spanish study,11 mortality during admission for bacteraemia due to OXA-48-producing enterobacteriaceae was 65%. Recently, a meta-analysis5 on infections caused by carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae placed gross mortality in bacteraemia at 54.30% (range: 47.51–61.02). In addition, mortality was linked to factors concerning the host, infection and antibiotic treatment.12

In our study, gross intrahospital mortality was 37%, which is lower than the data published. This could be due to various factors. First, our patients had few comorbidities with no serious underlying diseases and moderately serious infection. Second, the source of infection in our bacteraemia cohort was predominantly with low inoculum or in contexts in which management of the focus could be achieved.

Definitive antibiotic treatment, together with management of the focus of infection and prompt establishment of effective empirical antibiotic treatment, are the factors that determine the rate of mortality due to this type of infection.7,12 However, at present, definitive antibiotic treatment in serious infections due to carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae remains a subject of much debate due to a limited number of therapeutic options and a lack of randomised clinical trials. Recently, Paño-Pardo's working group13 demonstrated that combination therapy was associated with a lower mortality rate only in seriously ill patients, in whom the risk of mortality was very high. In less seriously ill patients, the use of combination therapy did not seem to show any advantages over monotherapy in terms of mortality. Contrasting with these results, our study found the use of combination therapy to be significantly associated with a lower mortality rate.

Regarding microbiological characteristics, in accordance with other case series published,11,14 our isolates had high resistance in vitro to all antibiotics; colistin, amikacin and gentamicin had the highest percentages of activity. In addition, awareness of the risk factors associated with CPE infections would aid in improving prevention and clinical management. Consistent with the findings of other authors,14,15 our patients had a long hospital stay, use of invasive procedures, prior surgery and KPOXA-48 rectal colonisation, which aided in guiding empirical treatment.

The limitations of the study are those inherent to its retrospective design and small number of patients enrolled. In addition, survival might have been overestimated as follow-up was limited to the time of the hospital stay and as gross intrahospital mortality was analysed. Finally, the limited variables collected in relation to treatment response made it difficult to evaluate treatment efficacy.

In conclusion, this study shows how KPOXA-48 may be involved in bacteraemia of nosocomial origin. It demonstrates the importance of suspecting and identifying this mechanism of resistance, as well as the risk factors of the patient, the type of bacteraemia and the adequacy of the treatment strategy in the clinical course of bacteraemia. Similarly, taking into account the seriousness of the infection, the identification of carriers and the strengthening of infection management practices are vitally important for preventing the spread of these microorganisms.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Madueño A, González-García J, Alonso Socas MM, Miguel Gómez MA, Lecuona M. Características y evolución clínica de las bacteriemias por Klebsiella pneumoniae productora de carbapenemasa tipo OXA-48 en un hospital de tercer nivel. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:498–501.