Bacterial meningitis is a serious condition that requires early antibiotic therapy. Its most frequent aetiology is Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis. It is rare for the responsible pathogen to have an animal reservoir, as is the case of Campylobacter fetus (C. fetus), whose reservoir is the digestive tract of cows and sheep, being a causal pathogen of zoonosis. Here we present a case of meningitis due to C. fetus.

The patient was a 59-year-old male smoker with no history of chronic alcohol consumption, hypertension or dyslipidaemia. He initially sought treatment for vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain. After three days of dietary measures, the symptoms of fever (up to 40 °C), headache, prostration and dysarthria persisted, for which complementary tests were carried out, in which CRP 27.3 mg/dl, procalcitonin 0.4 ng/ml and 9,629 103/ug leukocytes with left shift (86.9% neutrophils) stood out. With the suspicion of infection of the central nervous system, a cranial CT scan was performed, which showed a left frontotemporoparietal hypodense subdural haematoma of 17 mm with deviation from the midline and another right frontotemporoparietal haematoma of 5 mm. With these findings, empirical antibiotic coverage was started with ceftriaxone, ampicillin, linezolid and acyclovir, and urgent surgery was performed with drainage of the collections. Initially, the clinical and radiological course was favourable, with decreased collections and no deviation from the midline, so a lumbar puncture was performed on the third day of antibiotic therapy, with yellowish-looking fluid coming out, with 13 predominantly monomorphonuclear leukocytes (86%), with glucose consumption (52 mg/dl in CSF, capillary glycaemia being 116) with proteinuria (304 mg/dl) and an outlet pressure of 13 mmHg.

One week after admission, the patient began to present a new neurological deterioration consisting of greater dysarthria. EEG with pathological tracing was performed, adjusting anticonvulsant treatment. Growth was detected in the subdural fluid samples sent in blood culture bottles (bioMérieux), so a Gram stain was performed directly from the bottle, this being highly suggestive of Campylobacter spp. Seeding was carried out on PVX (bioMérieux) and COS (bioMérieux) plates with incubation for 24 h and subsequent reincubation for another 24 h with no growth. It was also seeded on Campylosel agar (CAM-bioMérieux), incubating in a hood with GENbox microaer sachets for 48 h, observing growth of colonies, subsequently proceeding to identification with the Vitek MS system (bioMérieux). Sensitivity studies were carried out on Mueller-Hinton 2 agar +5% sheep blood (MHS-bioMérieux) with disc-plate in microaerophilia (in a hood with GENbox micro-bioMérieux sachets), being sensitive to carbapenems, so antibiotic therapy was modified to meropenem 2 g every 8 h, with the patient subsequently presenting a favourable clinical course. Antibiotic therapy was completed for four weeks and the anticonvulsant dose could be lowered until withdrawal. Prior to discharge, a brain MRI was performed, which showed a persistent left parietal subdural haematoma and discreet right meningeal thickening, without clinical repercussions, so no new drainage was performed. In subsequent follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic.

C. fetus is a gram-negative bacillus found in the digestive tract of cattle and sheep, and can be transmitted after ingestion of contaminated food (such as milk or meat) or after direct contact with infected animals1. However, this contact with infected animals has only been identified in slightly more than half of the case2.

Meningitis due to C. fetus is infrequent (0.02 per million inhabitants) and usually occurs in people with compromised immunity, generally with a history of alcoholism, liver disease, advanced age, diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid treatment or neoplasia1.

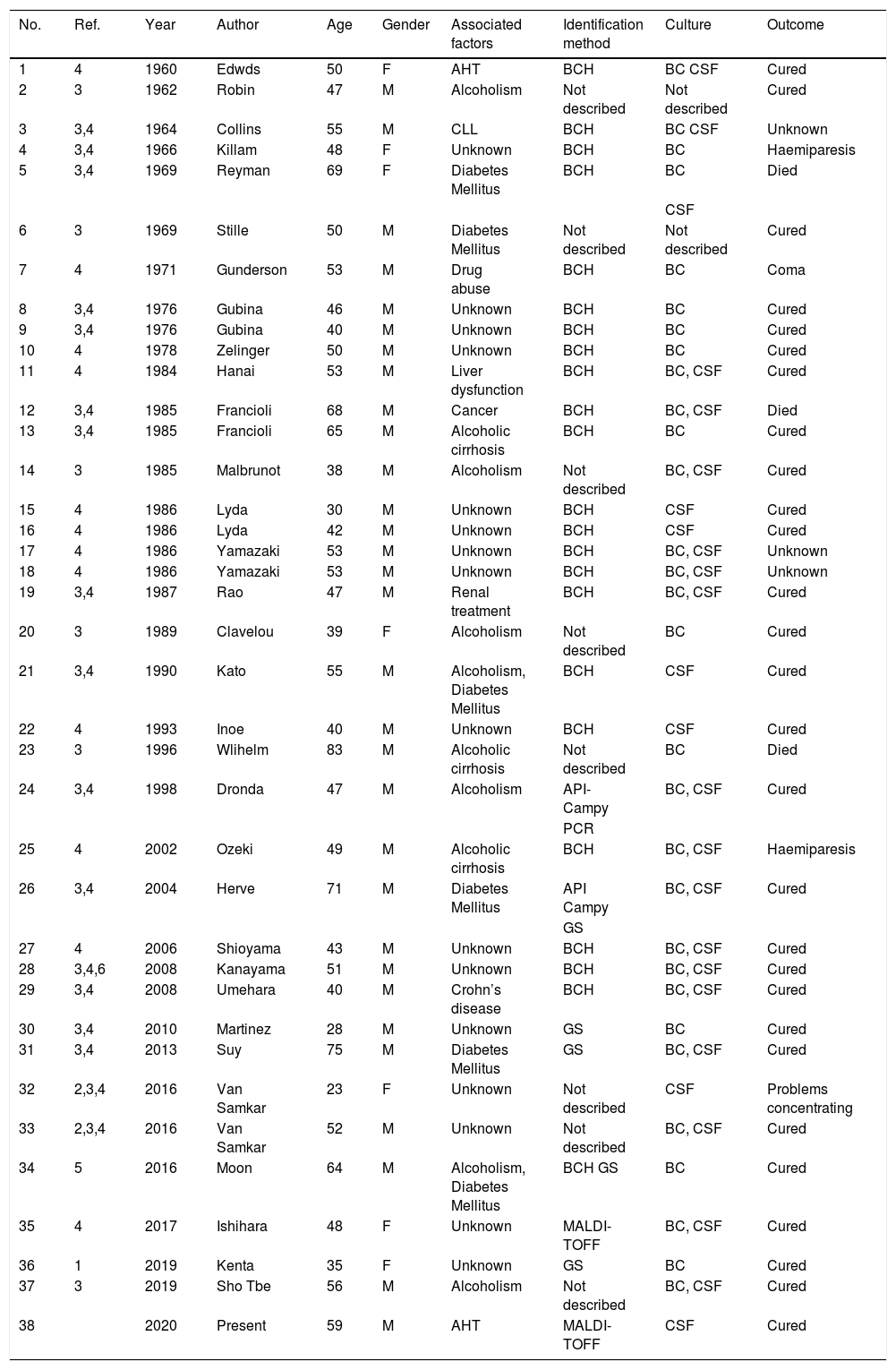

The first published case dates back to 1960, and since then 37 cases of meningitis due to C. fetus have been documented (Table 1)1–5, but only two case studies of empyema have been published6,7. Patients’ average age is 50 years, and the majority are male (81%). As a risk factor, 27% have a history of alcoholism, 16% have diabetes mellitus, whilst 43% of cases are healthy patients. Although all the patients presented alterations in the biochemistry of the cerebrospinal fluid, in many cases the culture of the cerebrospinal fluid was negative (in up to 9 cases the only isolation was in blood), whilst the blood culture was positive in 81% of the cases. In 18%, the isolation was only in cerebrospinal fluid. Regarding the outcome, 72% were cured and there were three deaths among the published cases.

Summary of the cases published to date of meningitis due to Campylobacter fetus.

| No. | Ref. | Year | Author | Age | Gender | Associated factors | Identification method | Culture | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 1960 | Edwds | 50 | F | AHT | BCH | BC CSF | Cured |

| 2 | 3 | 1962 | Robin | 47 | M | Alcoholism | Not described | Not described | Cured |

| 3 | 3,4 | 1964 | Collins | 55 | M | CLL | BCH | BC CSF | Unknown |

| 4 | 3,4 | 1966 | Killam | 48 | F | Unknown | BCH | BC | Haemiparesis |

| 5 | 3,4 | 1969 | Reyman | 69 | F | Diabetes Mellitus | BCH | BC | Died |

| CSF | |||||||||

| 6 | 3 | 1969 | Stille | 50 | M | Diabetes Mellitus | Not described | Not described | Cured |

| 7 | 4 | 1971 | Gunderson | 53 | M | Drug abuse | BCH | BC | Coma |

| 8 | 3,4 | 1976 | Gubina | 46 | M | Unknown | BCH | BC | Cured |

| 9 | 3,4 | 1976 | Gubina | 40 | M | Unknown | BCH | BC | Cured |

| 10 | 4 | 1978 | Zelinger | 50 | M | Unknown | BCH | BC | Cured |

| 11 | 4 | 1984 | Hanai | 53 | M | Liver dysfunction | BCH | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 12 | 3,4 | 1985 | Francioli | 68 | M | Cancer | BCH | BC, CSF | Died |

| 13 | 3,4 | 1985 | Francioli | 65 | M | Alcoholic cirrhosis | BCH | BC | Cured |

| 14 | 3 | 1985 | Malbrunot | 38 | M | Alcoholism | Not described | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 15 | 4 | 1986 | Lyda | 30 | M | Unknown | BCH | CSF | Cured |

| 16 | 4 | 1986 | Lyda | 42 | M | Unknown | BCH | CSF | Cured |

| 17 | 4 | 1986 | Yamazaki | 53 | M | Unknown | BCH | BC, CSF | Unknown |

| 18 | 4 | 1986 | Yamazaki | 53 | M | Unknown | BCH | BC, CSF | Unknown |

| 19 | 3,4 | 1987 | Rao | 47 | M | Renal treatment | BCH | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 20 | 3 | 1989 | Clavelou | 39 | F | Alcoholism | Not described | BC | Cured |

| 21 | 3,4 | 1990 | Kato | 55 | M | Alcoholism, Diabetes Mellitus | BCH | CSF | Cured |

| 22 | 4 | 1993 | Inoe | 40 | M | Unknown | BCH | CSF | Cured |

| 23 | 3 | 1996 | Wlihelm | 83 | M | Alcoholic cirrhosis | Not described | BC | Died |

| 24 | 3,4 | 1998 | Dronda | 47 | M | Alcoholism | API-Campy | BC, CSF | Cured |

| PCR | |||||||||

| 25 | 4 | 2002 | Ozeki | 49 | M | Alcoholic cirrhosis | BCH | BC, CSF | Haemiparesis |

| 26 | 3,4 | 2004 | Herve | 71 | M | Diabetes Mellitus | API Campy | BC, CSF | Cured |

| GS | |||||||||

| 27 | 4 | 2006 | Shioyama | 43 | M | Unknown | BCH | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 28 | 3,4,6 | 2008 | Kanayama | 51 | M | Unknown | BCH | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 29 | 3,4 | 2008 | Umehara | 40 | M | Crohn’s disease | BCH | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 30 | 3,4 | 2010 | Martinez | 28 | M | Unknown | GS | BC | Cured |

| 31 | 3,4 | 2013 | Suy | 75 | M | Diabetes Mellitus | GS | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 32 | 2,3,4 | 2016 | Van Samkar | 23 | F | Unknown | Not described | CSF | Problems concentrating |

| 33 | 2,3,4 | 2016 | Van Samkar | 52 | M | Unknown | Not described | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 34 | 5 | 2016 | Moon | 64 | M | Alcoholism, Diabetes Mellitus | BCH GS | BC | Cured |

| 35 | 4 | 2017 | Ishihara | 48 | F | Unknown | MALDI-TOFF | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 36 | 1 | 2019 | Kenta | 35 | F | Unknown | GS | BC | Cured |

| 37 | 3 | 2019 | Sho Tbe | 56 | M | Alcoholism | Not described | BC, CSF | Cured |

| 38 | 2020 | Present | 59 | M | AHT | MALDI-TOFF | CSF | Cured |

AHT: arterial hypertension, BC: blood cultures, BCH: biochemical, CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, F: female, GS: genetic sequencing, M: male, PCR: polymerase chain reaction, Ref.; bibliographic reference.

There is no established treatment protocol. In the publications reviewed, many patients were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy or combination therapy, but there have also been reports of patients cured after monotherapy with ampicillin or amoxicillin3. We could highlight the fact that a multicentre study identified an intermediate sensitivity or resistance of 12% to ampicillin, 80% to cefotaxime and 100% to erythromycin, as well as the fact that there are reported cases of C. fetus strains resistant to ceftriaxone, cefotaxime and penicillin. Some authors recommend treatment with carbapenems, as well as prolonged treatment2,5.

In conclusion, meningitis due to C. fetus is rare, but should not be ruled out even if we are dealing with a healthy patient with no apparent contact with infected animals, especially if associated with a digestive condition. Its treatment would be prolonged antibiotic therapy.

Please cite this article as: Fernández González R, Lorenzo-Vizcaya AM, Bustillo Casado M, Fernández-Rodríguez R. Meningitis y empiema subdural por Campylobacter fetus. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:212–213.