Brucellosis is a bacterial zoonotic disease caused by Brucella spp. Depending on the causative reservoir, is classified as B. abortus (cattle), B. mellitensis (goats and sheep), B. suis (pigs, reindeer, rodents) and B. canis (dogs).1 Transmission occurs by ingestion, inhalation or direct contact with animals or their products. The usual incubation period is 2–8 weeks but can range from 5 days to several months.2

The most common form of acute presentation is fever with generalized symptoms. It also causes abortion and reproductive failure. Chronic manifestations include osteoarticular infections, genitourinary and intra-abdominal abscesses, and infective endocarditis. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement has also been described, most commonly as meningitis or encephalitis.3

Brucellosis is a notifiable disease and is a major public health concern, especially for people living in resource-limited settings.4 However, the clinical index of suspicion for infections caused by Brucella spp. is low.

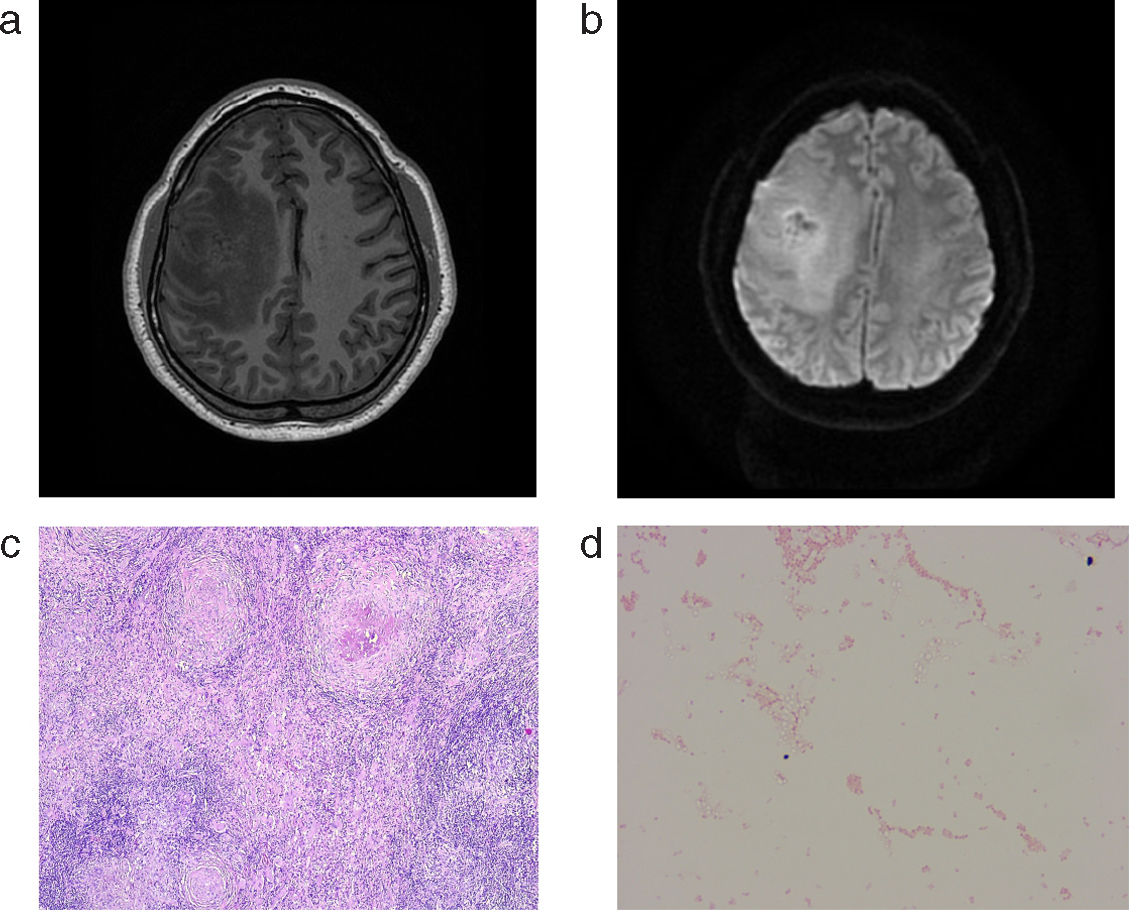

A 46-year-old peruvian man presented with epileptic seizures associated with left hemiparesis. Three months prior to admission, he reported an epileptic seizure for which he was evaluated in his home country. A CNS-MRI was performed and showed an anfractuous image with lobulated borders centered in the right middle frontal gyrus. Contrast showed diffuse enhancement with a multinodular pattern (Fig. 1a and b).

Surgical excision of the lesion was performed. Samples were sent for histologic analysis, which excluded malignancy and was reported as necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with negative Ziehl–Neelsen staining (Fig. 1c). Microbiologic studies included HIV, syphilis, HBV, HCV, Toxoplasma sp., Leishmania sp. serologies, Rose Bengal test and dimorphic fungal immunodiffusion, all of which were negative. On the biopsy specimen, PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Toxoplasma gondii, Histoplasma capsulatum, universal 16SrRNA gene and panfungal PCRs were all negative. Tuberculosis IGRA (Quantiferon-TB-Plus®) was positive and tuberculostatic treatment with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol was started.

Bacterial cultures were negative after 48h of incubation, but two weeks later small colonies of an oxidase-positive gram-negative cocci were detected on chocolate agar (Fig. 1d). Repeated attempts at identification by MALDI-TOF® using the standard database showed a good peak pattern but an unreliable score (below 1400). PCR of the complete 16S rRNA gene and sequencing were performed, resulting in the identification of Brucella sp. without species differentiation. Antibiotic treatment was then changed to rifampin at higher doses (900mg/day), doxycycline, and ceftriaxone at a dose of 2g IV every 12h for the first 4 weeks. The patient completed 4 months of treatment and subsequently had a favorable course, with no further neurologic symptoms or treatment-related adverse events.

Neurological manifestations of brucellosis are rare but may occur at any stage of systemic infection in a variety of clinical forms, including meningitis, meningoencephalitis, and cerebral or epidural abscess. In a series of 54 patients with neurobrucellosis, none presented with an intracranial mass.5 Case reports of intracranial abscesses due to Brucella sp. have been reported but are very rare.6,7

Diagnosis of brucellosis is made by isolation of the bacteria but is often complex. Brucella spp. is a fastidious intracellular microorganism, so recovery by conventional culture is not effective in many cases. Although serology is helpful in the diagnosis, a negative test does not exclude the disease, especially in chronic forms. Rose Bengal is an agglutination test that readily detects IgM immunoglobulins, and is positive in acute infections, but titers decreased significantly during follow-up.8

Another important point that emerges from our case is the lack of identification of Brucella sp. by MALDI-TOF® standard database, despite presenting a good score in the identification peaks. The lack of reference spectra in the currently commercialized databases does not allow the identification of Brucella sp. isolates.9 Therefore, in our case, we had to perform 16S PCR sequencing, which finally led us to the identification of Brucella sp. genus but was not able to distinguish between the species.

Finally, in the treatment of neurobrucellosis and infective endocarditis caused by Brucella sp., triple antimicrobial combination of doxycycline, rifampicin and cotrimoxazole for 4–6 months is recommended. In case of neurobrucellosis, substitution of cotrimoxazole by ceftriaxone in the first 4–6 weeks resulted in better evolution of patients and could shorten the duration of treatment to 4 months.10