American trypanosomiasis or Chagas disease is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi), a flagellated protozoan which is transmitted through the inoculation of faecal matter from triatomines. It can also be transmitted through blood products, organ transplants, orally or by transplacental transmission. If the acute form is not treated, the parasite remains latent and can lead to visceral complications in 30%–40% of people throughout their lives. In the case of immunosuppressed individuals, particularly in cellular immunosuppression, there is a risk of reactivation, which can cause serious complications with high mortality rates.1,2

We describe a case of T. cruzi-HIV coinfection in a patient with severe immunosuppression, suboptimal treatment with benznidazole and temporary discontinuation of antiretroviral treatment, with subsequent positive PCR for T. cruzi. The patient was a male in his sixties from Bolivia, diagnosed in September 2009 with stage C3 HIV infection (CD4+ 59 cells/mm3, 1,6%) manifesting with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and Cystoisospora belli diarrhoea, which were successfully treated for three weeks. During his admission he was also diagnosed with chronic Chagas disease in an indeterminate phase (positive ELISA and haemagglutination serology; positive T. cruzi PCR). Routine cardiology tests (electrocardiogram and echocardiogram) at initial screening were normal.

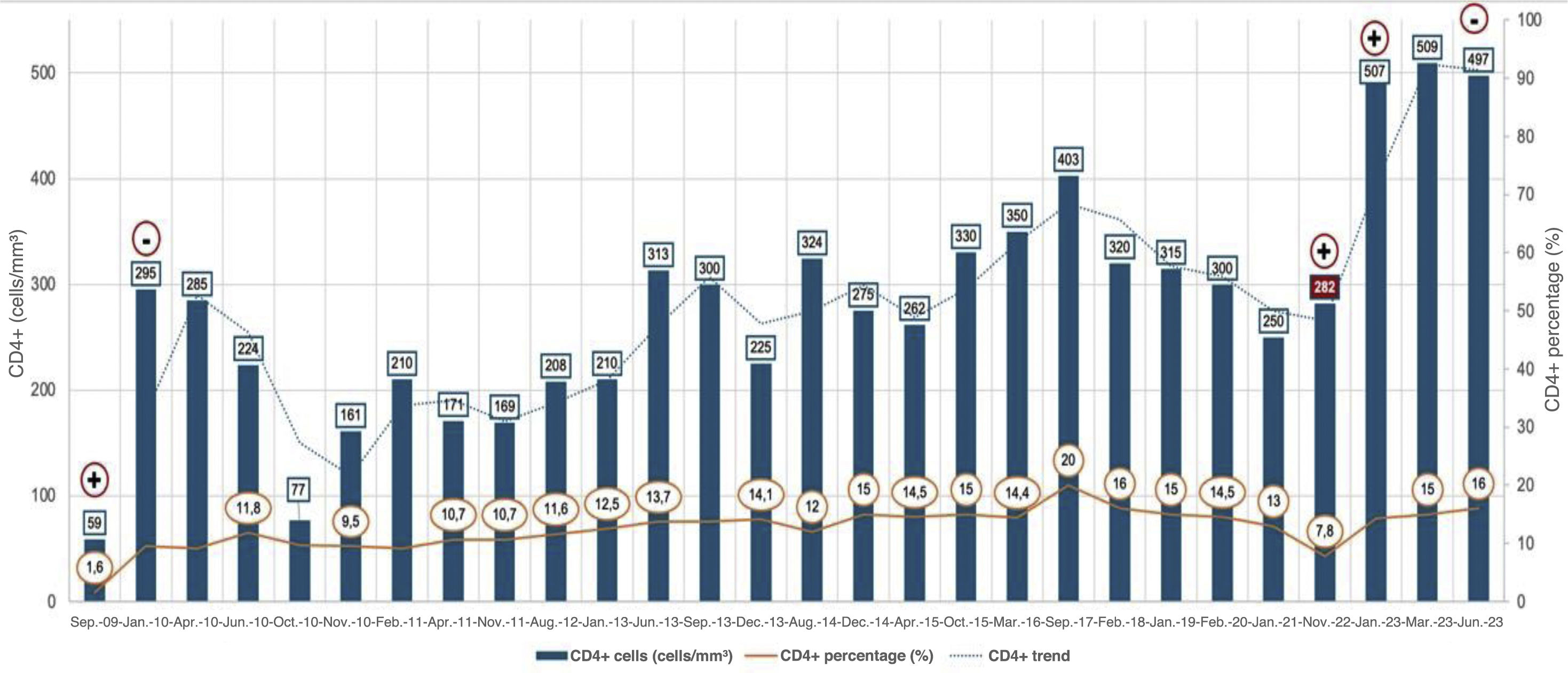

He was started on antiretroviral treatment (ART) with efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil (Atripla®), with progressive immune recovery, reaching CD4+ lymphocyte counts greater than 200 cells/mm3 after one month of treatment, achieving a CD4+ lymphocyte percentage of around 10% (Fig. 1). In November 2010, after one year of ART and a CD4 count+ of 161 cells/mm3 (9.5%), it was decided to start treatment for Chagas disease with benznidazole at a dose of 5&#¿;mg/kg/day. The treatment had to be discontinued after 15 days due to skin toxicity. PCR for T. cruzi was negative two months after stopping the treatment. During follow-up, an annual electrocardiogram, six-monthly echocardiogram and a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging scan were requested with no evidence of visceral involvement. The patient also did not develop any gastrointestinal symptoms during this time. After a progressive immune recovery CD4+ 403 cells/mm3 (20%), in November 2022, the patient stopped ART for two months, experiencing a viral rebound of up to 4.39 log and a decrease in CD4+ lymphocytes of 282 cells/mm3 (7.8%). At that time, a new PCR determination for T. cruzi was performed, which was positive. The ART was resumed with the regimen he was taking at that time, dolutegravir/lamivudine (Dovato®), achieving viral suppression once again and CD4+ immune restoration to 497 cells/mm3 (16%) up to his last check-up in September 2023. Despite this improvement in the patient’s immune and virological status, two other positive serial (from September to January 2024) PCR determinations for T. cruzi were found. Microbiological examination was extended with a blood study using Giemsa stain and Strout concentration test, with negative results. At no time did he show symptoms suggesting reactivation. At this time, a new treatment for Chagas disease was proposed with nifurtimox (8&#¿;mg/kg/day) and this was completed, although with several interruptions in the second month which extended the course of treatment by 15 days. The follow-up PCR after treatment was negative and remains so to date. His immune and virological status remained stable with undetectable viral load and CD4+ lymphocyte counts of 416 cells/mm3 (20%).

Chagas disease is endemic in continental Latin American countries. However, as a result of migration it has spread throughout the world, especially to Europe, where Spain is the country with the highest prevalence; in endemic areas the rate of T. cruzi-HIV coinfection is estimated to be between 1.3% and 7.12%.3 Reactivation of chronic Chagas disease occurs mainly in people with cellular immunosuppression and manifests as meningoencephalitis or myocarditis, with high morbidity and mortality rates.4,5 In patients with Chagas disease co-infected with HIV, reactivation usually occurs when the CD4 count+ drops to less than 200 cells/mm3. The risk of reactivation without ART is 15%–35%.4,6 However, a positive blood PCR result is not considered a definitive criterion for reactivation, as in 30%–70% of patients under follow-up this commonly occurs during the indeterminate chronic phase.4,5 For the diagnosis of reactivation in people with HIV, direct visualisation of trypomastigotes in peripheral blood or CSF, detection of positive PCR for T. cruzi in CSF or histological findings with the presence of inflammatory foci and amastigotes are necessary, usually being accompanied by clinical manifestations such as fever, meningoencephalitis, myocarditis or skin lesions.3,5

To reduce morbidity and mortality rates, it is recommended to start antiparasitic treatment early, with benznidazole 5&#¿;mg/kg/day being the treatment of choice or, alternatively, nifurtimox 8–10&#¿;mg/kg/day for 60 days. In cases of severe meningoencephalitis, benznidazole doses may be increased up to 10&#¿;mg/kg/day. No cases of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome have been reported with early initiation of ART, so there is no need to wait until the end of antiparasitic treatment to administer ART.3,7 The main problem with benznidazole treatment is the high rates of adverse effects (up to 52%) in adults, and treatment interruptions (up to 14%).8 Clinical trials have been conducted with shorter regimens, of up to two weeks, with the aim of reducing toxicity and facilitating treatment.9,10 The main limitation of these studies is that sustained negativity of T. cruzi PCR is used as the outcome. Although this strategy allows for clinical trials with manageable samples and follow-up periods, PCR techniques have not been shown to be surrogate markers of cure, at least not in moderate/advanced Chagas disease.11

Chagas disease should be screened for in immunosuppressed individuals from endemic areas due to the risk of disease progression and the possibility of reactivation. If detected, treatment is highly recommended, preferably with benznidazole. The duration of treatment in chronic Chagas disease is currently subject to debate. However, until more information is available on the clinical efficacy of treatment regimens shorter than two months, it is advisable to err on the side of caution, especially in patients with immunosuppression or at risk of becoming immunosuppressed.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll the authors made substantial contributions to each of the following: 1) data collection; 2) critical review of the intellectual content; and 3) final approval of the version submitted.

FundingNo funding was received.