The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is classified as a group 1 carcinogen. The main route of EBV transmission is oral, through saliva. The present study aimed to determine the frequency of EBV detection in the oral cavity in high school students in the city of Cali (Colombia).

Materials and methodsAnalytical cross-sectional study in order to determine the frequency of EBV detection in the oral cavity, the reasons for its prevalence and its association with several factors, in 1565 individuals. The variables analyzed were sociodemographic factors, oral hygiene, oral health, sexual behavior, cigarrete smoking and alcohol intake. The association between the EBV detection and the variables evaluated was done through a generalized linear regression model with logarithmic linkage and Poisson distribution with robust variance.

ResultsThe percentage of exposure to EBV in the oral cavity was 38.40% (CI 95%: 36.02–40.84). The frequency of presenting EBV exposure was 22% higher in men and the risk increased according to sexual behaviour. An inverse association with the school grade was found: the eleventh-grade participants had 27% less frequency of exposure to EBV than the lower grades (sixth to eighth). When analyzing the logistic model to study the association between EBV detection and independent variables, the association was overestimated. The overestimation ranged from 27% to 47% depending on the type of variable.

ConclusionsThe frequency of EBV detection in the oral cavity of healthy students was similar to that previously described. Factors associated to sexual behavior increased the risk of opportunity to be exposed to EBV.

El virus de Epstein-Barr (VEB) está clasificado como carcinógeno del grupo 1. Su principal vía de transmisión es la oral, a través de la saliva. Determinamos la frecuencia de detección del VEB en la cavidad oral en estudiantes de secundaria en Cali (Colombia).

Materiales y metodosEstudio transversal analítico para estimar la frecuencia de detección del genoma del VEB en cavidad oral, las razones de prevalencia y su asociación con diversos factores en 1.565 individuos. Las variables analizadas fueron factores sociodemográficos, de higiene y salud oral, comportamiento sexual, consumo de cigarrillos e ingesta de alcohol. La asociación entre la detección y las variables evaluadas se realizó mediante un modelo de regresión lineal generalizado con vínculo logarítmico y distribución de Poisson con varianza robusta.

ResultadosLa exposición al VEB en la cavidad oral fue del 38,40% (IC 95%: 36,02-40,84). La frecuencia de presentar exposición al VEB fue un 22% mayor en los varones, y el riesgo se incrementó según el comportamiento sexual. Se encontró asociación inversa con el grado escolar: los participantes de undécimo grado tuvieron un 27% menos frecuencia de exposición al VEB que los de grados inferiores (sexto a octavo). Cuando se utilizó el modelo logístico para estudiar la asociación entre la detección del VEB y las variables independientes, se sobreestimó la asociación. El rango de sobreestimación fue entre el 27-47% según el tipo de variable.

ConclusionLa frecuencia de detección del VEB en la cavidad oral de estudiantes sanos fue similar a la previamente descrita. Factores asociados al comportamiento sexual incrementan el riesgo de oportunidad para la exposición al VEB.

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), or herpesvirus type 4 (species: human Gammaherpesvirus 4, genus: Lymphocryptovirus, family Herpesviridae, order: Herpesvirales)1, is the leading cause of acute infectious mononucleosis, a common syndrome characterised by fever, sore throat, extreme fatigue and inflamed lymph nodes2. EBV is commonly transmitted by contact with the saliva of a carrier of the virus. Its incubation period may be up to 40 days. The virus can remain active for several hours and can often be detected in the saliva of carriers, hence its alternate name, the “kissing disease”3,4.

Serology tests that detect EBV antibodies have shown EBV infection to have a bimodal distribution according to age of primary infection, with incidence peaking at two to four years of age and at 14–18 years of age5–7. A study conducted in adolescents 13–14 years of age in Guadalajara (Spain), published in 2001, found a prevalence of EBV antibodies of 73.5% (confidence interval [CI]: 67.9%–78.5%) with no significant differences by sex8. EBV is commonly acquired in childhood or early adolescence, when it is difficult to detect as the infection is usually asymptomatic and therefore often indistinguishable from other mild childhood diseases2. However, when EBV is acquired in adolescence or adulthood, acute infectious mononucleosis develops in 30%–70% of cases, sometimes with serious symptoms9.

EBV is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer10. This herpesvirus has been found to be associated with diseases of the oral cavity such as Burkitt lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and hairy leukoplakia11. Some studies have suggested that, in people who have had infectious mononucleosis, the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma increases significantly with EBV detection, with a relative risk of 4.0 (95% CI: 3.4–4.5) and an average time from mononucleosis to Hodgkin lymphoma with EBV detection of 4.1 years (95% CI: 1.8–8.3)12. According to GLOBOCAN (International Agency for Research on Cancer Information System) statistics, in 2018 in Colombia, roughly 743 patients presented Hodgkin lymphoma and roughly 216 patients died of this disease13.

Therefore, given the potential clinical consequences of EBV infection in adolescence, this study sought to determine the association between the rate of EBV detection in the oral cavity and the distribution thereof by age, sex, school grade, hygiene habits, oral health, cigarette use, alcohol intake and sexual behaviour in secondary school students in the city of Cali (Colombia).

Materials and methods Type of studyThis study was conducted according to a cross-sectional design for data analysis of the information collected. It was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health of Universidad del Valle [University of Valle] (approval minutes numbers: 011-014 [2014], 008-017 [2017] and 022-018 [2018]).

Study populationThe study population corresponded to adolescent students 14–17 years of age attending educational institutions in the city of Cali who met the inclusion criteria for the study as specified in the “Information collection” section.

The participating students were in the sixth to the eleventh grades in Colombia, equivalent to year seven to year 12 in the United Kingdom and the sixth to the eleventh grades in the United States.

Sample sizeThe sample size required to be able to perform bilateral tests for comparing proportions with a 95% confidence level (1-alpha) and a statistical power of 80% was estimated at 1565 individuals. The rate of EBV detection in the oral cavity of 45%, reported in a 2019 study by Giraldo-Ocampo et al. in a group of secondary students, was taken as the reference group rate.14 The study group rate was assumed to be equal to 0.5, as the rate of association with the study risk factors was unknown.

Information collectionBoth the biological sample and the epidemiological information recorded in the database on socio-demographic characteristics and risk factors were obtained with non-probabilistic sampling, as educational institutions registered with the municipal secretariat of education of Cali (Colombia) were invited to participate. This means that convenience sampling was done, as biological samples were taken and surveys administered in the secondary schools that allowed their students to be invited. In order to be able to take part in the study, the adolescents had to meet the following inclusion criteria: being secondary students attending educational institutions registered with the municipal secretariat of education of Cali, being 14–17 years of age and agreeing to participate in the study by reading and signing an informed consent form. They also had to meet none of the exclusion criteria: being students whose legal representative denied their participation in the study by reading and not signing the informed consent form.

Biological sampling consisting of the use of mouthwash in the oral cavity and gargling for 30 s with distilled water, then extraction of genetic material using the PrepMan® Ultra Sample Preparation Reagent extraction kit (Applied Biosystems™) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To protect the students’ privacy and confidentiality, they were not asked for their names at any point during sample collection or survey administration; in addition, the students filled in the surveys themselves. Each student’s biological sample and survey were marked with the same coding to be identified in subsequent analyses.

Epstein–Barr virus detectionEBV was detected using the following molecular methods:

- a)

First: viral DNA detection was performed by conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers EBV-F; 5′-CCT GGT CAT CCT TTG CCA-3′ and EBV-R; 5′-TGC TTC GTT ATA GCC GTA GT-3′ proposed by Kato et al. in 2015.15 In the conventional PCR a 95pb fragment was amplified and the reaction was performed in a final volume of 20 μl with the following final concentrations: 1X GoTaq Green buffer, 1.9 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP’s, 0.25 μM of each primer, 1U of Taq polymerase (BioTaq, Bioline) and the addition of 1 μl (∼50 ng/μl) of DNA. Amplification was performed in a Swift™ MiniPro Thermal Cycler using the following concentrations: initial denaturing at 95 °C for two minutes followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension of two minutes at 72 °C. The amplified product was run on 3% agarose gel with a concentration of 1:10,000X of the EZ-Vision® intercalator, through electrophoresis for 50 min at 100 V, using 1X TBE buffer. The gel was visualised with a UV transilluminator. For the negative control, Milli-Q water was added in place of DNA. The minimum limit of detection of the conventional PCR was evaluated by preparing a series of dilutions (10−1, 10−2, 10−3 and 10−4) from a positive control for EBV previously quantified and validated by direct Sanger sequencing and analysis of percentages of identity using the BLASTn algorithm through alignment with EBV reference sequences (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy/?term=EBV).

- b)

Second: to avoid false negatives due to low viral loads in samples, DNA samples with negative conventional PCR results were evaluated using real-time PCR, employing the same primers and using a CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). The reaction was performed in a final volume of 20 μl containing 10 μl of SYBR Selected Master Mix for CFX (2X) from Applied Biosystems (SYBR® GreenER™, AmpliTaq® DNA polymerase, UDG, dNTP’s with dUTP/dTTP and optimised buffer components), 0.4 μM of each primer and 1 μl (∼50 ng/μl) of DNA, under the following conditions: initial denaturing at 95 °C for 10 s, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for five seconds and 60 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for five minutes. The specificity of the amplified product was confirmed by means of dissociation or melting curve analysis.

The database obtained was subjected to review and quality control. According to the dictionary of variables, missing data, duplicate data, data outside identified values and data not permitted as well as coherence between variables were taken into account. For the bivariate analysis, estimates of association between the dependent variable (EBV detection) and the categorical independent variables were made through a bivariate analysis of 2 × 2 tables for dichotomous variables, with the chi-squared test, and 2 × R tables for polychotomous independent variables, with Fisher’s exact test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. In the multivariate analysis, Poisson, binomial, negative binomial and logistic regression models were used under the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). In addition, overestimation was calculated according to the model. The Stata® statistics software package, ver. 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, United States), was used.

ResultsThe quality control to which the database was subjected did not change the total number of 1565 study population records. The response variable of the study — the rate of EBV exposure in the oral cavity — was 38.40% with a 95% CI of 36.02%–40.84%.

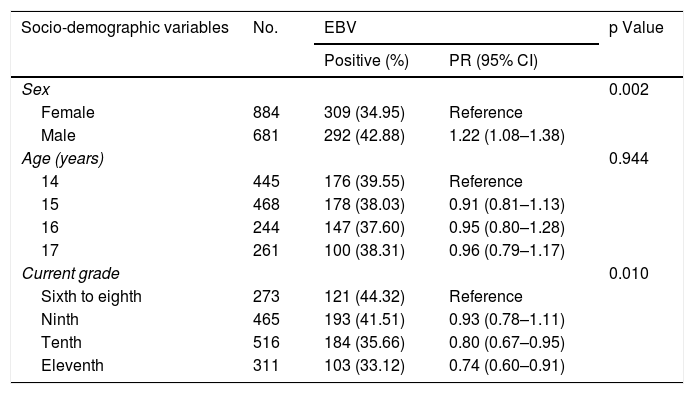

Bivariate analysisTable 1 shows the results of the analysis of association between EBV detection and the socio-demographic component variables. Of the 1565 study records, 292 (42.9%) of 681 male students and 309 (34.9%) of 884 female students tested positive for EBV in the oral cavity. Males showed a 22% higher rate of EBV exposure than females (PR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.08−1.38; p: 0.002).

Analysis of association between positive EBV detection and socio-demographic component variables.

| Socio-demographic variables | No. | EBV | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (%) | PR (95% CI) | |||

| Sex | 0.002 | |||

| Female | 884 | 309 (34.95) | Reference | |

| Male | 681 | 292 (42.88) | 1.22 (1.08–1.38) | |

| Age (years) | 0.944 | |||

| 14 | 445 | 176 (39.55) | Reference | |

| 15 | 468 | 178 (38.03) | 0.91 (0.81–1.13) | |

| 16 | 244 | 147 (37.60) | 0.95 (0.80–1.28) | |

| 17 | 261 | 100 (38.31) | 0.96 (0.79–1.17) | |

| Current grade | 0.010 | |||

| Sixth to eighth | 273 | 121 (44.32) | Reference | |

| Ninth | 465 | 193 (41.51) | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) | |

| Tenth | 516 | 184 (35.66) | 0.80 (0.67–0.95) | |

| Eleventh | 311 | 103 (33.12) | 0.74 (0.60–0.91) | |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; PR: prevalence ratio.

Positive results for EBV were seen in 176 (39%) of 445 students 14 years of age, representing the highest rate in terms of age for this variable.

By contrast, 147 (37.6%) of 244 students 16 years of age were positive for EBV, corresponding to the lowest rate of EBV detection. However, this age-based difference in virus detection rates was not statistically significant. For the school grade variable, 121 (44%) of 273 students in the sixth to the eighth grades were found to be positive for EBV, whereas 103 (33%) of 311 students in the eleventh grade tested positive for the virus. The students in the tenth grade had a 20% lower rate of EBV exposure than the students in the sixth to the eighth grades (PR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.6−0.95); meanwhile, the students in the eleventh grade had a 26% lower rate of EBV exposure than the students in the sixth to the eighth grades (PR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.60−0.91).

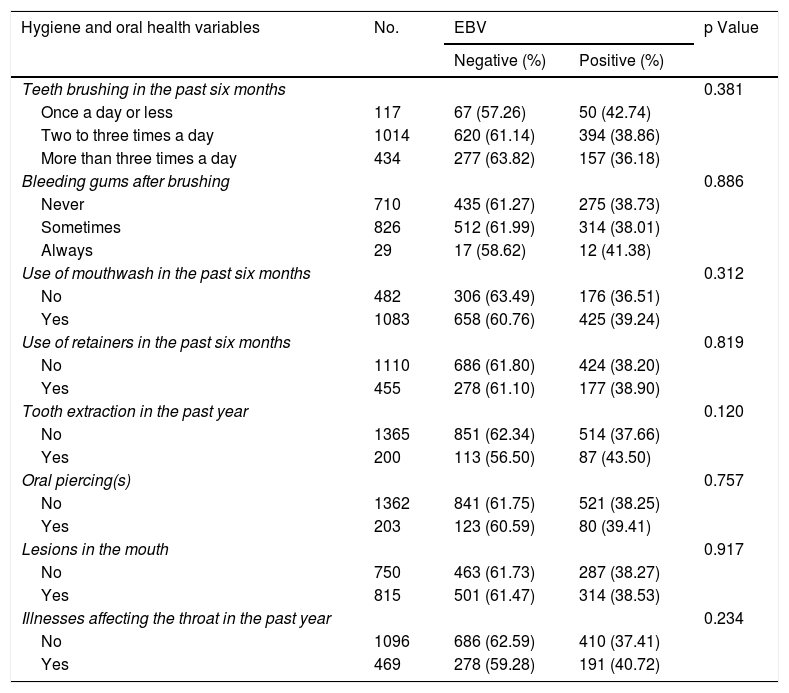

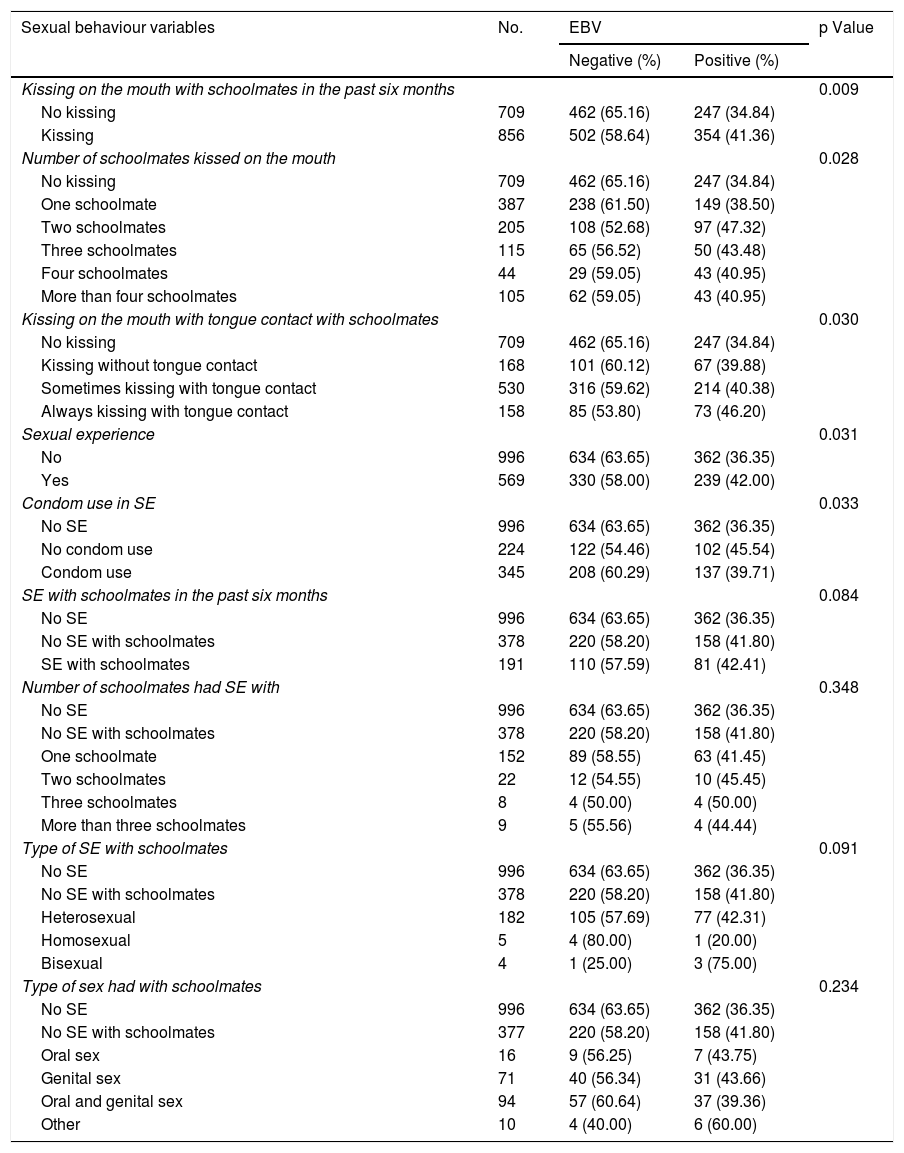

Table 2 shows the results of the analyses of association between EBV detection and the hygiene and oral health component variables. None of the variables in these components exhibited a statistically significant association with EBV detection in the oral cavity (p > 0.05). Among the 1565 study records, 50 (42.7%) of 117 students who only brushed their teeth once a day or less were positive for EBV; this rate was higher than that found in those who brushed their teeth more than once a day. Students who reported persistent bleeding gums had a higher rate of EBV detection (41.3%). Similarly, students who reported illnesses affecting the throat also had a higher rate of EBV detection compared to those without such diseases — 40.7% versus 37%, respectively. Table 3 shows the results of the analyses of association between EBV detection and the sexual behaviour component variables. Of the 1565 study records, the majority of the sexual behaviour variables were significantly associated with EBV detection. Kissing a schoolmate on the mouth in the past six months had an 18% higher rate of association with EBV exposure than no kissing (p = 0.009). Kissing more than two schoolmates had a 30% higher rate of association with EBV exposure than no kissing (p = 0.028).

Analysis of association between positive EBV detection and hygiene and oral health component variables.

| Hygiene and oral health variables | No. | EBV | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (%) | Positive (%) | |||

| Teeth brushing in the past six months | 0.381 | |||

| Once a day or less | 117 | 67 (57.26) | 50 (42.74) | |

| Two to three times a day | 1014 | 620 (61.14) | 394 (38.86) | |

| More than three times a day | 434 | 277 (63.82) | 157 (36.18) | |

| Bleeding gums after brushing | 0.886 | |||

| Never | 710 | 435 (61.27) | 275 (38.73) | |

| Sometimes | 826 | 512 (61.99) | 314 (38.01) | |

| Always | 29 | 17 (58.62) | 12 (41.38) | |

| Use of mouthwash in the past six months | 0.312 | |||

| No | 482 | 306 (63.49) | 176 (36.51) | |

| Yes | 1083 | 658 (60.76) | 425 (39.24) | |

| Use of retainers in the past six months | 0.819 | |||

| No | 1110 | 686 (61.80) | 424 (38.20) | |

| Yes | 455 | 278 (61.10) | 177 (38.90) | |

| Tooth extraction in the past year | 0.120 | |||

| No | 1365 | 851 (62.34) | 514 (37.66) | |

| Yes | 200 | 113 (56.50) | 87 (43.50) | |

| Oral piercing(s) | 0.757 | |||

| No | 1362 | 841 (61.75) | 521 (38.25) | |

| Yes | 203 | 123 (60.59) | 80 (39.41) | |

| Lesions in the mouth | 0.917 | |||

| No | 750 | 463 (61.73) | 287 (38.27) | |

| Yes | 815 | 501 (61.47) | 314 (38.53) | |

| Illnesses affecting the throat in the past year | 0.234 | |||

| No | 1096 | 686 (62.59) | 410 (37.41) | |

| Yes | 469 | 278 (59.28) | 191 (40.72) | |

EBV: Epstein–Barr virus.

Analysis of association between positive EBV detection and sexual behaviour component variables.

| Sexual behaviour variables | No. | EBV | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (%) | Positive (%) | |||

| Kissing on the mouth with schoolmates in the past six months | 0.009 | |||

| No kissing | 709 | 462 (65.16) | 247 (34.84) | |

| Kissing | 856 | 502 (58.64) | 354 (41.36) | |

| Number of schoolmates kissed on the mouth | 0.028 | |||

| No kissing | 709 | 462 (65.16) | 247 (34.84) | |

| One schoolmate | 387 | 238 (61.50) | 149 (38.50) | |

| Two schoolmates | 205 | 108 (52.68) | 97 (47.32) | |

| Three schoolmates | 115 | 65 (56.52) | 50 (43.48) | |

| Four schoolmates | 44 | 29 (59.05) | 43 (40.95) | |

| More than four schoolmates | 105 | 62 (59.05) | 43 (40.95) | |

| Kissing on the mouth with tongue contact with schoolmates | 0.030 | |||

| No kissing | 709 | 462 (65.16) | 247 (34.84) | |

| Kissing without tongue contact | 168 | 101 (60.12) | 67 (39.88) | |

| Sometimes kissing with tongue contact | 530 | 316 (59.62) | 214 (40.38) | |

| Always kissing with tongue contact | 158 | 85 (53.80) | 73 (46.20) | |

| Sexual experience | 0.031 | |||

| No | 996 | 634 (63.65) | 362 (36.35) | |

| Yes | 569 | 330 (58.00) | 239 (42.00) | |

| Condom use in SE | 0.033 | |||

| No SE | 996 | 634 (63.65) | 362 (36.35) | |

| No condom use | 224 | 122 (54.46) | 102 (45.54) | |

| Condom use | 345 | 208 (60.29) | 137 (39.71) | |

| SE with schoolmates in the past six months | 0.084 | |||

| No SE | 996 | 634 (63.65) | 362 (36.35) | |

| No SE with schoolmates | 378 | 220 (58.20) | 158 (41.80) | |

| SE with schoolmates | 191 | 110 (57.59) | 81 (42.41) | |

| Number of schoolmates had SE with | 0.348 | |||

| No SE | 996 | 634 (63.65) | 362 (36.35) | |

| No SE with schoolmates | 378 | 220 (58.20) | 158 (41.80) | |

| One schoolmate | 152 | 89 (58.55) | 63 (41.45) | |

| Two schoolmates | 22 | 12 (54.55) | 10 (45.45) | |

| Three schoolmates | 8 | 4 (50.00) | 4 (50.00) | |

| More than three schoolmates | 9 | 5 (55.56) | 4 (44.44) | |

| Type of SE with schoolmates | 0.091 | |||

| No SE | 996 | 634 (63.65) | 362 (36.35) | |

| No SE with schoolmates | 378 | 220 (58.20) | 158 (41.80) | |

| Heterosexual | 182 | 105 (57.69) | 77 (42.31) | |

| Homosexual | 5 | 4 (80.00) | 1 (20.00) | |

| Bisexual | 4 | 1 (25.00) | 3 (75.00) | |

| Type of sex had with schoolmates | 0.234 | |||

| No SE | 996 | 634 (63.65) | 362 (36.35) | |

| No SE with schoolmates | 377 | 220 (58.20) | 158 (41.80) | |

| Oral sex | 16 | 9 (56.25) | 7 (43.75) | |

| Genital sex | 71 | 40 (56.34) | 31 (43.66) | |

| Oral and genital sex | 94 | 57 (60.64) | 37 (39.36) | |

| Other | 10 | 4 (40.00) | 6 (60.00) | |

EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; SE: sexual experience.

Students who reported sometimes kissing with tongue contact had a 15% higher rate of EBV exposure than students who reported no kissing (p = 0.03), and students who reported always kissing with tongue contact had a 32% higher rate of EBV exposure than students who reported no kissing (p = 0.03).

The variable of condom use in sexual relations showed a 20% higher rate of EBV exposure than not having had sexual relations (p = 0.03). No other sexual behaviour component variable was associated with EBV detection in the oral cavity of the participants.

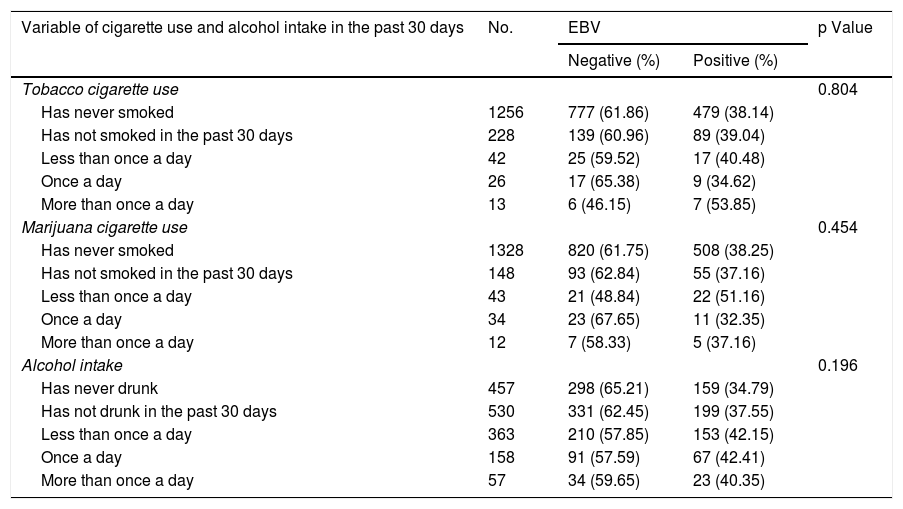

Table 4 shows the results of the analyses of association between EBV detection and the cigarette use and alcohol intake variables. None of the variables of the cigarette, tobacco, marijuana and alcohol use component showed a statistically significant association with EBV detection in the oral cavity (p > 0.05).

Analysis of association between positive EBV detection and cigarette use and alcohol intake component variables.

| Variable of cigarette use and alcohol intake in the past 30 days | No. | EBV | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (%) | Positive (%) | |||

| Tobacco cigarette use | 0.804 | |||

| Has never smoked | 1256 | 777 (61.86) | 479 (38.14) | |

| Has not smoked in the past 30 days | 228 | 139 (60.96) | 89 (39.04) | |

| Less than once a day | 42 | 25 (59.52) | 17 (40.48) | |

| Once a day | 26 | 17 (65.38) | 9 (34.62) | |

| More than once a day | 13 | 6 (46.15) | 7 (53.85) | |

| Marijuana cigarette use | 0.454 | |||

| Has never smoked | 1328 | 820 (61.75) | 508 (38.25) | |

| Has not smoked in the past 30 days | 148 | 93 (62.84) | 55 (37.16) | |

| Less than once a day | 43 | 21 (48.84) | 22 (51.16) | |

| Once a day | 34 | 23 (67.65) | 11 (32.35) | |

| More than once a day | 12 | 7 (58.33) | 5 (37.16) | |

| Alcohol intake | 0.196 | |||

| Has never drunk | 457 | 298 (65.21) | 159 (34.79) | |

| Has not drunk in the past 30 days | 530 | 331 (62.45) | 199 (37.55) | |

| Less than once a day | 363 | 210 (57.85) | 153 (42.15) | |

| Once a day | 158 | 91 (57.59) | 67 (42.41) | |

| More than once a day | 57 | 34 (59.65) | 23 (40.35) | |

EBV: Epstein–Barr virus.

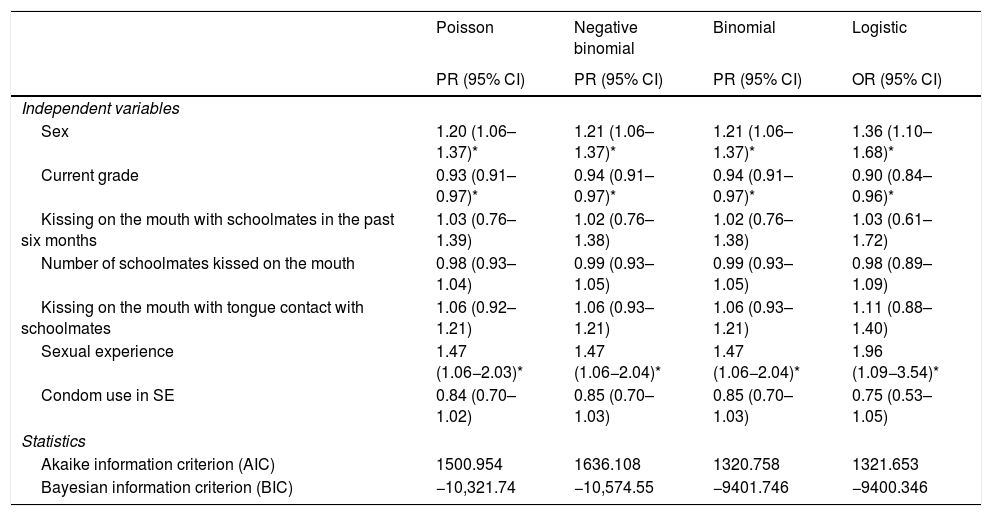

Table 5 shows the results of the comparison of the multivariate analyses to model the factors associated with EBV exposure in the oral cavity of the students. The results obtained with the four models showed an equal direction of association between the variables of sex, school grade and having had sexual relations on the one hand and the presence of EBV in the oral cavity of the students on the other hand. However, the magnitude of association was overestimated by up to 25% when the logistic model was used to examine the relationship between EBV and these variables. The independent variables associated with higher rates of EBV detection in the oral cavity, according to the regression models, were: being a male student, being in the sixth through the eighth grades and having had sexual relations. In relation to the AIC and BIC, it was found that the binomial model had the lowest AIC value and the negative binomial model had the lowest BIC value. With the Poisson model, with robust variance, the confidence intervals were narrower.

Regression models with robust estimation for EBV exposure in the oral cavity of students 14–17 years of age attending educational institutions in Cali.

| Poisson | Negative binomial | Binomial | Logistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Sex | 1.20 (1.06–1.37)* | 1.21 (1.06–1.37)* | 1.21 (1.06–1.37)* | 1.36 (1.10–1.68)* |

| Current grade | 0.93 (0.91–0.97)* | 0.94 (0.91–0.97)* | 0.94 (0.91–0.97)* | 0.90 (0.84–0.96)* |

| Kissing on the mouth with schoolmates in the past six months | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) | 1.02 (0.76–1.38) | 1.02 (0.76–1.38) | 1.03 (0.61–1.72) |

| Number of schoolmates kissed on the mouth | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 0.98 (0.89–1.09) |

| Kissing on the mouth with tongue contact with schoolmates | 1.06 (0.92–1.21) | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) | 1.11 (0.88–1.40) |

| Sexual experience | 1.47 (1.06−2.03)* | 1.47 (1.06−2.04)* | 1.47 (1.06−2.04)* | 1.96 (1.09−3.54)* |

| Condom use in SE | 0.84 (0.70–1.02) | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 0.75 (0.53–1.05) |

| Statistics | ||||

| Akaike information criterion (AIC) | 1500.954 | 1636.108 | 1320.758 | 1321.653 |

| Bayesian information criterion (BIC) | −10,321.74 | −10,574.55 | −9401.746 | −9400.346 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; OR: odds ratio; PR: prevalence ratio; SE: sexual experience.

When the exposure variables were modelled by strata, estimates were similar with Poisson, binomial and negative binomial regression, but the CI tended to be narrower, and therefore estimation was more precise with Poisson regression.

In the Poisson model with robust variance in Table 6, males showed a 19% higher rate of EBV exposure than females (PR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.05–1.36), whereas logistic regression showed (OR: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.10−1.68). Comparison of the magnitude of association of the two models with logistic regression revealed that the association between sex and EBV exposure was overestimated by 47%. With the Poisson model with robust variance, the students in the tenth grade had a 22% lower rate of EBV exposure compared to students in the sixth through the eighth grades, whereas with logistic regression the rate of EBV exposure was 34% lower; for this variable, the association was overestimated by 27%.

Robust Poisson regression models and overestimation of logistic regression for EBV exposure in the oral cavity in students 14–17 years of age in secondary schools in Cali (Colombia).

| Independent variables | Poissona | Logistic | Difference (OR–PR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | Absolute | Overestimation (%) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Reference | |||||

| Male | 1.19 | 1.05–1.35 | 1.36 | 1.10–1.68 | 0.17 | 47 |

| Current grade | ||||||

| Sixth to eighth | Reference | |||||

| Ninth | 0.94 | 0.79–1.11 | 0.89 | 0.66–1.21 | 0.17 | 45 |

| Tenth | < | 0.65−0.93 | 0.66 | 0.48–0.89 | 0.12 | 27 |

| Eleventh | 0.73 | 0.59–0.90 | 0.59 | 0.48–0.89 | 0.14 | 34 |

| Kissing on the mouth with schoolmates | ||||||

| No kissing | Reference | |||||

| Kissing | 1.16 | 0.86–1.55 | 1.04 | 0.62–1.53 | ||

| Number of schoolmates kissed on the mouth | ||||||

| No kissing | Reference | |||||

| One schoolmate | 1.00 | 0.77–1.31 | 1.02 | 0.64–1.61 | 0.02 | 10 |

| Two schoolmates | 1.18 | 0.90–1.54 | 1.35 | 0.83–2.21 | 0.17 | 49 |

| Three schoolmates | 1.08 | 0.79–1.47 | 1.16 | 0.67–2.00 | 0.08 | 50 |

| Four schoolmates | 0.85 | 0.53–1.36 | 0.76 | 0.37–1.64 | 0.09 | 37 |

| Kissing on the mouth with tongue contact with schoolmates | ||||||

| No kissing | Reference | |||||

| Kissing without tongue contact | 0.91 | 0.70–1.18 | 0.84 | 0.52–1.42 | 0.07 | 43 |

| Sometimes kissing with tongue contact | 0.91 | 0.74–1.10 | 0.84 | 0.58–1.21 | 0.07 | 43 |

| Always kissing with tongue contact | 1.00 | |||||

| Sexual experience | ||||||

| No | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 1.07 | 0.91−1.26 | 1.12 | 0.85−1.47 | 0.05 | 41.6 |

| Condom use in SE | ||||||

| No SE | Reference | |||||

| No condom use | 1.18 | 0.97–1.42 | 1.34 | 0.94–1.9 | 0.16 | 47 |

| Condom use | 1.00 | |||||

| Statistics | ||||||

| Akaike information criterion (AIC) | 1505.715 | 1321.65 | ||||

| Bayesian information criterion (BIC) | −10,282.16 | −9400.34 | ||||

Overestimation of OR with respect to PR was calculated using the following formula: Overestimation = (OR–PR)/(OR–1).24

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; OR: odds ratio; PR: prevalence ratio; SE: sexual experience.

The rate of EBV exposure in the oral cavity in adolescents (14–17 years of age) attending educational institutions in Cali was 38.40% (95% CI: 36.02%–40.84%). A 2015 study conducted by Kato et al. in Japan15 detected EBV DNA in 45% of a group of individuals in good periodontal health and in 80% of patients with chronic periodontitis. In populations with disease, a 2010 study by Arreaza et al.16 estimated EBV detection rates of 50% in patients with oral lichen planus lesions and 10% in the healthy/control group. Similarly, in a 2015 study in patients with airway or gastrointestinal tract cancer, Veitía et al.17 found the EBV genome in the oral cavity in 40.90%, in the larynx in 31.8% and in the oropharynx in 27.27% of these patients.

The results of this study suggest that the rate of detection of the virus in the oral cavity in healthy students in the city of Cali (Colombia) is similar to that normally detected in individuals in good periodontal health in Japan, but also similar to the rate of detection found in biopsies in patients with airway or gastrointestinal tract cancer.

The results for the sexual behaviour variables were consistent with those of other published studies18, where EBV seroprevalence increased significantly in individuals who were sexually active, especially those with numerous sexual partners. The hygiene and oral health variables yielded no statistically significant findings; however, some studies have found that, in developed countries with high hygiene standards, EBV seroconversion peaks in children two to four years of age and adolescents 14–18 years of age and increases with age, ranging from 0% to 70% in childhood and exceeding 90% in adulthood. By contrast, in countries with low hygiene standards, EBV infection is generally acquired in early childhood, and nearly all children in developing countries are seropositive by six years of age6,7,19–21.

For the grade in school variable, a higher risk of EBV detection in the oral cavity was found in the lower grades; this might have been due to the fact that EBV exposure rates are higher in younger children, as their immune systems have not come into contact with the virus and have not mounted a response. This was not seen in students in upper grades, who might have mounted a response as a result of having come into contact with the virus.

Prevalence studies are used in biomedical research to estimate association between dichotomous dependent variables (EBV exposure or non-exposure) and one or more independent variables. The odds ratio (OR) and the prevalence ratio (PR) are the classically reported association measures. Although both reflect degrees of association, they are interpreted differently. The PR shows how many times likelier exposed individuals are to have the disease or condition compared to non-exposed individuals. In this regard, in cross-sectional designs, when the dependent variable is dichotomous, the prevalence is generally obtained in the descriptive analysis, and therefore the PR is more intuitive and easier to understand. The OR, for its part, is defined as the odds of exposed individuals having or not having the disease or condition compared to the odds of non-exposed individuals having or not having it22,23.

In this study, OR was not a good estimator of PR, as the rate of EBV detection was high (38.4%; 95% CI: 36.0%–40.8%)24. Under these circumstances, it is not a good idea to use the logistic regression model to examine the association between EBV presence and predictive variables. It is advisable to use Poisson regression models and to be sure to have used robust methods for estimating the variance thereof; otherwise, Poisson regression will yield wider confidence intervals compared to a log-binomial regression model25.

When the logistic model was used to examine the association between EBV detection and the independent variables, the estimators overestimated the association. Table 6 shows the study of the factors related to EBV exposure using different regression models. When the estimators obtained were compared to the Poisson regression model with robust estimation, the logistic regression model was seen to overestimate the association between the presence of EBV DNA and the factors examined. The magnitude of this overestimation was 27%–47%, depending on the type of variable examined. Overestimation may unduly influence clinical decision-making and policy development and therefore lead to involuntary errors in the economic analysis of possible intervention and treatment programmes25.

One limitation of the study was its cross-sectional design, which made it impossible to arrive at temporal associations or conclusions between the predictive variables and the outcome variable. In addition, the reliability of the data was somewhat uncertain as the students filled in the survey themselves, carrying a risk of memory bias. Finally, convenience sampling precluded estimation of the prevalence of EBV exposure in students in the city of Cali (Colombia).

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that the rate of detection of EBV in the oral cavity in healthy students in the city of Cali (Colombia) is similar to that normally detected in individuals in good periodontal health. They also suggest that factors associated with sexual behaviour increase the opportunity risk of EBV exposure in the oral cavity. These results are important in public health for demarcating healthcare priorities and drawing up plans for EBV prevention and control, as well as identifying risk factors in adolescents in the city of Cali. Characterising the population of adolescents 14–17 years of age in terms of socio-demographics, hygiene, oral health, cigarette use, alcohol intake and sexual behaviour offered insights into biological, psychological and social factors related to the presence of this virus in the oral cavity. As the study data were collected in 2015–2016, this study provides a baseline for determining changes in EBV exposure in adolescents in the city of Cali (Colombia).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the Vice-Rector’s Office for Research of the Universidad del Valle (project CI 71114) and the Departamento Administrativo de Ciencias y Tecnologías de Colombia [Administrative Department of Science and Technology of Colombia] (COLCIENCIAS) (project 1106-657-41213. CT-664-2014) for their financial support.

Please cite this article as: Castillo A, Giraldo S, Guzmán N, Bravo LE. Factores asociados a la presencia del virus de Epstein-Barr en la cavidad oral de adolescentes de la ciudad de Cali (Colombia). Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:113–120.