Dalbavancin (DBV), a novel lipoglycopeptide with activity against Gram-positive bacterial infections, is approved for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSIs). It has linear dose-related pharmacokinetics allowing a prolonged interval between doses. It would be a good option for the treatment of patients with Gram-positive cardiovascular infections.

MethodsRetrospective analysis of patients with cardiovascular infection (infective endocarditis, bacteremia, implantable electronic device infection) treated with DBV at Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid) for 7 years (2016–2022). Patients were divided in two study groups: 1) Infective endocarditis (IE), 2) Bacteremia. Epidemiological, clinical, microbiological and therapeutic data were analyzed.

ResultsA total of 25 patients were treated with DBV for cardiovascular infection. IE was the most common indication (68%), followed by bacteremia (32%) with male predominance in both groups (64% vs 62%) and median age of 67,7 and 57,5 years, respectively. 100% of blood cultures were positive to Gram-positive microorganisms (Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp. or Enterococcus spp.) in both study groups. Previously to DBV, all patients received other antibiotic therapy, both in the group of IE (median: 80 days) as in bacteremia (14,8 days). The main reason for the administration of DBV was to continue intravenous antimicrobial therapy outside the hospital in both the EI group (n&#¿;=&#¿;15) and the bacteremia group (n&#¿;=&#¿;8). DBV was used as consolidation therapy in a once- or twice-weekly regimen. Microbiological and clinical successes were reached in 84% of cases (n&#¿;=&#¿;21), 76,4% in IE group and 100% in bacteremia group. No patient documented adverse effects during long-term dalbavancin treatment.

ConclusionDBV is an effective and safety treatment as consolidation antibiotic therapy in IE and bacteremia produced by Gram-positive microorganisms.

Dalbavancina (DBV) es un nuevo lipoglicopéptido con eficacia frente a Gram-positivos, cuyo uso está aprobado para el tratamiento de las infecciones de piel y partes blandas (IPPBs). Su farmacocinética lineal permite un amplio intervalo entre dosis. Constituye una prometedora alternativa como terapia antibiótica en pacientes con infección cardiovascular por cocos Gram-positivos.

Material y metodosEstudio retrospectivo de pacientes con infección cardiovascular (bacteriemia, infección de dispositivos de estimulación cardiaca o endocarditis infecciosa) que recibieron tratamiento con DBV en el Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid durante 7 años (2016-2022). Se dividió a los pacientes en 2 grupos de estudio: 1) Endocarditis infecciosa (EI), 2) Bacteriemia. Se analizaron variables epidemiológicas, clínicas, microbiológicas y de tratamiento.

ResultadosUn total de 25 pacientes recibieron tratamiento con DBV por un episodio de infección cardiovascular. La EI fue la indicación más frecuente (68%), seguido de la bacteriemia (32%), con un predominio de varones en ambos grupos (64% vs 62%) y una edad media de 67,7 y 57,5 años, respectivamente. El 100% de aislamientos en hemocultivos fue por cocos Gram-positivos (Staphylococcus spp, Streptococcus spp o Enterococcus spp) en ambos grupos de estudio. Previamente a DBV, todos los pacientes recibieron antibioterapia parenteral, tanto en el grupo de EI (media: 80 días), como en el de bacteriemia (media: 14,8 días). El motivo principal para la administración de DBV fue con objetivo de continuación de tratamiento antibiótico intravenoso fuera del hospital tanto en el grupo de EI (n&#¿;=&#¿;15), como en el de bacteriemia (n&#¿;=&#¿;8). En todos los casos DBV se utilizó como terapia de consolidación, en tratamiento semanal o quincenal. Se documentó curación clínica y microbiológica en el 84% de los casos (n&#¿;=&#¿;21), 76,4% en el grupo de EI y 100% en el de bacteriemia. No se documentó ningún efecto adverso asociado a la administración de DBV.

ConclusionDBV es un antibiótico eficaz y seguro como terapia de consolidación en el tratamiento de la EI y de la bacteriemia producida por microorganismos Gram-positivos.

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a serious disease associated with high morbidity and mortality, which currently accounts for 65,000 deaths per year.1 Its incidence has increased over time, as has the occurrence of significant changes in the clinical and microbiological profile of episodes.1–4 Staphylococci are the most frequently implicated genus of microorganism to cause IE, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most common causative microorganism in Spain. The cornerstone of IE treatment is antibiotic therapy, which must be administered intravenously and for a prolonged period of time (4–6 weeks),5 with valve replacement surgery sometimes necessary given the aggressiveness of the disease and its complications.

Bacteraemia caused by Gram-positive cocci is one of the most common nosocomial infections, increasing morbidity and mortality in hospitalised patients by 12–25%.6

Dalbavancin (DBV) is a new lipoglycopeptide antibiotic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2014 and the European Medicines Agency in 2015 for the treatment of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs).7,8 This antibiotic has proven in vitro efficacy against multiple Gram-positive microorganisms, including methicillin-resistant staphylococci and strains with intermediate susceptibility to vancomycin, viridans group streptococci, beta-haemolytic streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae and enterococci, as well as anaerobic Gram-positive bacilli and cocci. DBV has a minimum inhibitory concentration of 0.06&#¿;mg/l against coagulase-negative staphylococci and 16 times lower than vancomycin against beta-haemolytic streptococci.9 The pharmacokinetics of DBV are linear in relation to the dose administered, with an elimination half-life of 346&#¿;hours, allowing for a wide interdose interval of up to two weeks, depending on the dose administered.10,11 It is therefore a promising alternative as a consolidation therapy in patients with stable Gram-positive cocci IE.

The aim of this study was to describe the clinical and microbiological profile of patients who have received DBV as treatment for cardiovascular infection, their clinical outcomes and safety.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective, observational, single-centre study that included patients over 18 years of age at Hospital Clínico San Carlos in Madrid who were treated with DBV between 1 January 2016 and 27 September 2022, and who required hospital admission. Hospital Clínico San Carlos is a tertiary care public hospital administered by the Madrid Health Service. It is also a reference centre for healthcare training at the Complutense University of Madrid.

From this group, patients who were treated with at least one dose of DBV for a documented episode of cardiovascular infection were selected.

Patients were then divided into two main diagnostic groups: 1) IE (native valve, prosthetic valve, device-related or vascular graft), and 2) bacteraemia (primary or catheter-related).

IE was diagnosed according to the 2015 European Society of Cardiology criteria,5 while device-related IE was diagnosed according to the 2020 European Heart Rhythm Association consensus document criteria.12 Vascular graft infection was defined by clinical criteria, compatible radiological diagnostic imaging (CT) and microbiological isolation in blood samples and/or percutaneous aspirate or explanted graft material.13

Bacteraemia was defined as at least two positive blood cultures for the same microorganism in the absence of IE, and catheter-related bacteraemia when the same microorganism was identified in the catheter tip culture.6,14

Epidemiological, clinical and microbiological characteristics were collected from the review of patient medical records.

Clinical cure was defined as the absence of symptoms or signs of infection in probable relation to the disease that led to treatment with DBV, and microbiological cure as the absence of growth of the same microorganism in blood cultures within six months of diagnosis, after completion of treatment.

Treatment failure was defined as a lack of response to the antibiotic therapy administered, either due to persistent IE-related symptoms (heart failure, valve dysfunction and/or vegetation imaging >10&#¿;mm or finding of systemic embolisms) or persistent bacteraemia despite appropriate parenteral antibiotic therapy.

Reinfection was defined as the onset of a new episode of IE or bacteraemia caused by the same microorganism that caused the initial episode more than six months after diagnosis.

The patients were followed up clinically and microbiologically in the outpatient clinic of our centre after discharge from hospital, once antibiotic therapy had been completed.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos of Madrid (code: 23/057-E) and complied with the ethical precepts established in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables with normal distribution are expressed in terms of mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range. Categorical variables are presented in terms of absolute number and percentage. The analysis was performed using the statistical software SPSS® 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsDescription of the populationBetween 2016 and 2022, 59 patients at our centre were treated with DBV, of whom cardiovascular infection was documented in 25 (42.3%), constituting our study group. In the remaining cases (57.7%), DBV was administered due to: osteoarticular infection (osteomyelitis, septic arthritis) (40.6%) and/or SSTIs (17.1%).

In total, 64% were male with a mean age of 64.4 years (range: 40–89 years) and a mean Charlson index of 4.5 (range: 0–14). Some 44% had vascular grafts (prosthetic heart valves, pacemakers or stents). IE was the most frequent indication (68%), followed by catheter-related bacteraemia (24%). All blood culture isolates (100%) were Gram-positive cocci.

Patients with infective endocarditisA total of 17 cases of IE were recorded, six of which were on native valve and eight on prosthetic valve. Two cases of device-related IE and one vascular graft infection were reported. Some 64.7% were male and the mean age was 67.7 years (range: 40–89 years; SD 14.32); 70% were older than 65 years. The most common comorbidities were, in order of frequency: cardiovascular disease (82%), solid organ neoplasia (41%), respiratory disease (23%) and diabetes mellitus (11.7%). The mean Charlson index was 3.8 (SD 1.97). The main clinical and epidemiological characteristics of IE patients treated with DBV are shown in Table 1.

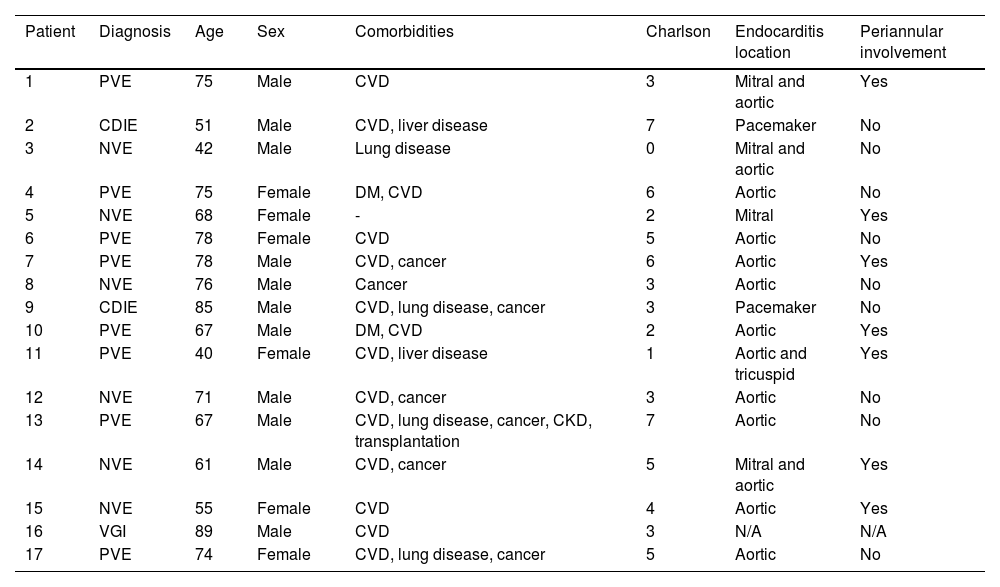

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with infective endocarditis treated with dalbavancin.

| Patient | Diagnosis | Age | Sex | Comorbidities | Charlson | Endocarditis location | Periannular involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PVE | 75 | Male | CVD | 3 | Mitral and aortic | Yes |

| 2 | CDIE | 51 | Male | CVD, liver disease | 7 | Pacemaker | No |

| 3 | NVE | 42 | Male | Lung disease | 0 | Mitral and aortic | No |

| 4 | PVE | 75 | Female | DM, CVD | 6 | Aortic | No |

| 5 | NVE | 68 | Female | - | 2 | Mitral | Yes |

| 6 | PVE | 78 | Female | CVD | 5 | Aortic | No |

| 7 | PVE | 78 | Male | CVD, cancer | 6 | Aortic | Yes |

| 8 | NVE | 76 | Male | Cancer | 3 | Aortic | No |

| 9 | CDIE | 85 | Male | CVD, lung disease, cancer | 3 | Pacemaker | No |

| 10 | PVE | 67 | Male | DM, CVD | 2 | Aortic | Yes |

| 11 | PVE | 40 | Female | CVD, liver disease | 1 | Aortic and tricuspid | Yes |

| 12 | NVE | 71 | Male | CVD, cancer | 3 | Aortic | No |

| 13 | PVE | 67 | Male | CVD, lung disease, cancer, CKD, transplantation | 7 | Aortic | No |

| 14 | NVE | 61 | Male | CVD, cancer | 5 | Mitral and aortic | Yes |

| 15 | NVE | 55 | Female | CVD | 4 | Aortic | Yes |

| 16 | VGI | 89 | Male | CVD | 3 | N/A | N/A |

| 17 | PVE | 74 | Female | CVD, lung disease, cancer | 5 | Aortic | No |

CDIE: cardiac device-related infective endocarditis; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; N/A: not applicable; NVE: native valve endocarditis; PVE: prosthetic valve endocarditis; VGI: vascular graft infection.

The most frequent microorganisms in order of frequency within the IE group were: coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (35%), methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (17%), Enterococcus faecalis (17%) and viridans group streptococci (17%). There was one case of methicillin-resistant S. aureus bacteraemia.

Prior to DBV antibiotic therapy, all IE patients received parenteral antibiotic therapy in monotherapy or in combination, with a median duration of 80 days (range: 7–730 days; SD 164.62). The most frequently used antibiotics were beta-lactams, in monotherapy or in combination (n&#¿;=&#¿;13), and daptomycin, in monotherapy or in combination (n&#¿;=&#¿;7). An aminoglycoside was combined with initial beta-lactam antibiotic therapy in four cases, and in two cases combination therapy with rifampicin was prescribed.

The mean length of hospital stay was 45 days (range: 7–150 days; SD 34) for the IE group. Valve replacement surgery or endovascular device removal was indicated in 60% of patients and was performed in 48% of cases. The mean length of hospital stay in surgically treated patients was 35.4 days (range: 7–91 days; SD 21.72).

DBV doses administered were: 500, 1,000 or 1,500&#¿;mg, with a mean number of doses of 3.47 (range: 1–12 doses; SD 3.23) and a total duration of 96 weeks (mean 5.6; range: 1–24 weeks; SD 5.57).

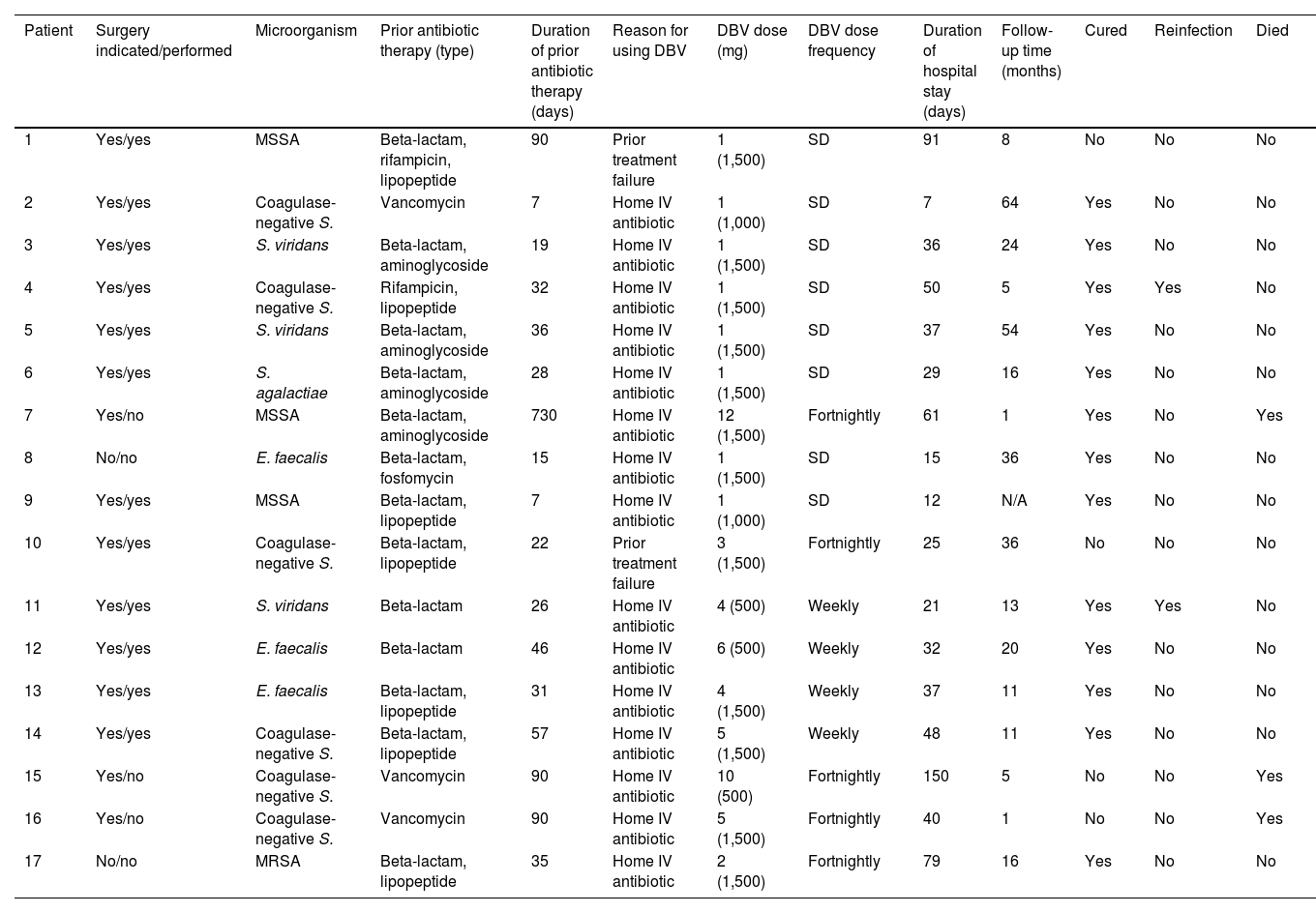

The duration of DBV antibiotic therapy, dose administered and frequency, as well as the clinical course of the patients and the microbiological profile of IE episodes, are shown in Table 2.

Type of treatment, clinical course and microbiological profile of infective endocarditis patients treated with dalbavancin.

| Patient | Surgery indicated/performed | Microorganism | Prior antibiotic therapy (type) | Duration of prior antibiotic therapy (days) | Reason for using DBV | DBV dose (mg) | DBV dose frequency | Duration of hospital stay (days) | Follow-up time (months) | Cured | Reinfection | Died |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes/yes | MSSA | Beta-lactam, rifampicin, lipopeptide | 90 | Prior treatment failure | 1 (1,500) | SD | 91 | 8 | No | No | No |

| 2 | Yes/yes | Coagulase-negative S. | Vancomycin | 7 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,000) | SD | 7 | 64 | Yes | No | No |

| 3 | Yes/yes | S. viridans | Beta-lactam, aminoglycoside | 19 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 36 | 24 | Yes | No | No |

| 4 | Yes/yes | Coagulase-negative S. | Rifampicin, lipopeptide | 32 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 50 | 5 | Yes | Yes | No |

| 5 | Yes/yes | S. viridans | Beta-lactam, aminoglycoside | 36 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 37 | 54 | Yes | No | No |

| 6 | Yes/yes | S. agalactiae | Beta-lactam, aminoglycoside | 28 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 29 | 16 | Yes | No | No |

| 7 | Yes/no | MSSA | Beta-lactam, aminoglycoside | 730 | Home IV antibiotic | 12 (1,500) | Fortnightly | 61 | 1 | Yes | No | Yes |

| 8 | No/no | E. faecalis | Beta-lactam, fosfomycin | 15 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 15 | 36 | Yes | No | No |

| 9 | Yes/yes | MSSA | Beta-lactam, lipopeptide | 7 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,000) | SD | 12 | N/A | Yes | No | No |

| 10 | Yes/yes | Coagulase-negative S. | Beta-lactam, lipopeptide | 22 | Prior treatment failure | 3 (1,500) | Fortnightly | 25 | 36 | No | No | No |

| 11 | Yes/yes | S. viridans | Beta-lactam | 26 | Home IV antibiotic | 4 (500) | Weekly | 21 | 13 | Yes | Yes | No |

| 12 | Yes/yes | E. faecalis | Beta-lactam | 46 | Home IV antibiotic | 6 (500) | Weekly | 32 | 20 | Yes | No | No |

| 13 | Yes/yes | E. faecalis | Beta-lactam, lipopeptide | 31 | Home IV antibiotic | 4 (1,500) | Weekly | 37 | 11 | Yes | No | No |

| 14 | Yes/yes | Coagulase-negative S. | Beta-lactam, lipopeptide | 57 | Home IV antibiotic | 5 (1,500) | Weekly | 48 | 11 | Yes | No | No |

| 15 | Yes/no | Coagulase-negative S. | Vancomycin | 90 | Home IV antibiotic | 10 (500) | Fortnightly | 150 | 5 | No | No | Yes |

| 16 | Yes/no | Coagulase-negative S. | Vancomycin | 90 | Home IV antibiotic | 5 (1,500) | Fortnightly | 40 | 1 | No | No | Yes |

| 17 | No/no | MRSA | Beta-lactam, lipopeptide | 35 | Home IV antibiotic | 2 (1,500) | Fortnightly | 79 | 16 | Yes | No | No |

DBV: dalbavancin; IV: intravenous; N/A: not applicable (follow-up in another centre); MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; SD: single dose.

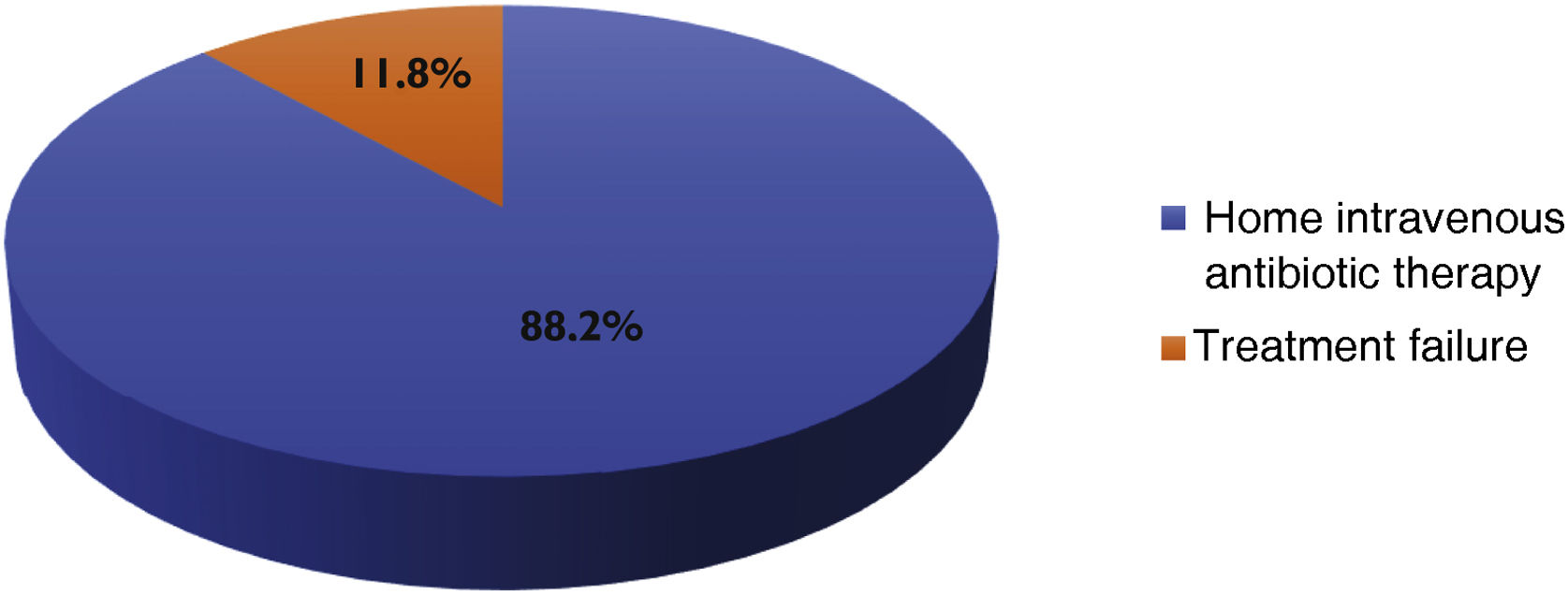

Reasons for DBV administration in the IE group were continuation of intravenous antibiotic therapy outside the hospital (n&#¿;=&#¿;15) or previous treatment failure (n&#¿;=&#¿;2).

In all cases, DBV was administered on the day of discharge, either as a single dose or as a starting dose. The results of the reason for DBV use are shown in Fig. 1.

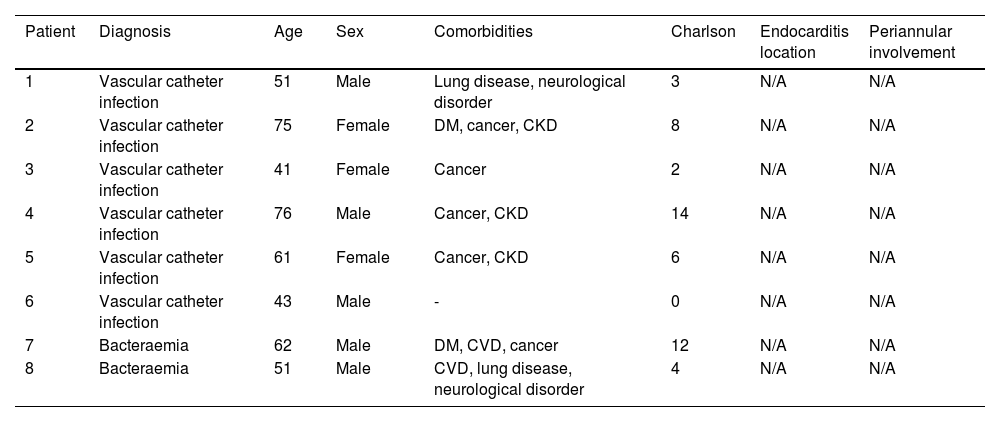

Patients with bacteraemiaIn the group of patients with bacteraemia, a total of eight episodes were documented, six of which were catheter-related bacteraemia and two were primary bacteraemia. In total, 62.5% were male, with a mean age of 57.5 years (range: 41–76 years; SD 12.48). The most common comorbidities were solid organ neoplasia (62%) and chronic kidney disease (37.5%), with a mean Charlson index of 6.1 (SD 4.59). The main clinical and epidemiological characteristics of bacteraemia patients treated with DBV are shown in Table 3.

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of bacteraemia patients treated with dalbavancin.

| Patient | Diagnosis | Age | Sex | Comorbidities | Charlson | Endocarditis location | Periannular involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vascular catheter infection | 51 | Male | Lung disease, neurological disorder | 3 | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | Vascular catheter infection | 75 | Female | DM, cancer, CKD | 8 | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | Vascular catheter infection | 41 | Female | Cancer | 2 | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | Vascular catheter infection | 76 | Male | Cancer, CKD | 14 | N/A | N/A |

| 5 | Vascular catheter infection | 61 | Female | Cancer, CKD | 6 | N/A | N/A |

| 6 | Vascular catheter infection | 43 | Male | - | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | Bacteraemia | 62 | Male | DM, CVD, cancer | 12 | N/A | N/A |

| 8 | Bacteraemia | 51 | Male | CVD, lung disease, neurological disorder | 4 | N/A | N/A |

CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; N/A: not applicable.

The most frequently isolated microorganisms were coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (62%), followed by S. aureus (25%). One methicillin-resistant S. aureus bacteraemia was documented.

Prior to DBV antibiotic therapy, all patients with bacteraemia received parenteral antibiotic therapy in monotherapy or in combination, with a mean duration of 14.8 days (range: 5–35 days; SD 9.06). The most commonly used antibiotics were beta-lactams, in monotherapy or in combination (n&#¿;=&#¿;7), and daptomycin, in monotherapy or in combination (n&#¿;=&#¿;6).

The mean hospital stay was 22.6 days (range: 7–41; SD 9.49) in the bacteraemia group.

DBV doses administered were: 500, 1,000 or 1,500&#¿;mg, with a mean number of doses of 1.12 (range: 1–2; SD 0.33) and a total duration of 16 weeks (mean 2; range: 1–4; SD 0.86).

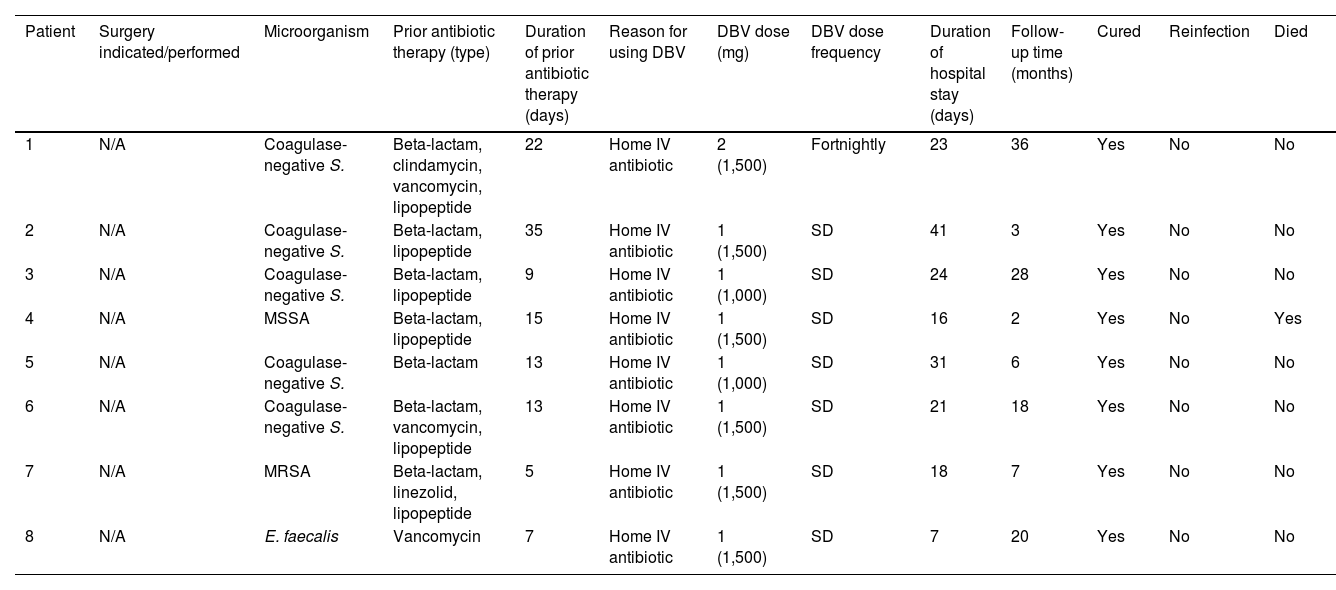

The duration of antibiotic therapy with DBV, dose administered and frequency, as well as the clinical course of the patients and the microbiological profile of the bacteraemia episodes, are shown in Table 4.

Type of treatment, clinical course and microbiological profile of bacteraemia patients treated with dalbavancin.

| Patient | Surgery indicated/performed | Microorganism | Prior antibiotic therapy (type) | Duration of prior antibiotic therapy (days) | Reason for using DBV | DBV dose (mg) | DBV dose frequency | Duration of hospital stay (days) | Follow-up time (months) | Cured | Reinfection | Died |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A | Coagulase-negative S. | Beta-lactam, clindamycin, vancomycin, lipopeptide | 22 | Home IV antibiotic | 2 (1,500) | Fortnightly | 23 | 36 | Yes | No | No |

| 2 | N/A | Coagulase-negative S. | Beta-lactam, lipopeptide | 35 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 41 | 3 | Yes | No | No |

| 3 | N/A | Coagulase-negative S. | Beta-lactam, lipopeptide | 9 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,000) | SD | 24 | 28 | Yes | No | No |

| 4 | N/A | MSSA | Beta-lactam, lipopeptide | 15 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 16 | 2 | Yes | No | Yes |

| 5 | N/A | Coagulase-negative S. | Beta-lactam | 13 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,000) | SD | 31 | 6 | Yes | No | No |

| 6 | N/A | Coagulase-negative S. | Beta-lactam, vancomycin, lipopeptide | 13 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 21 | 18 | Yes | No | No |

| 7 | N/A | MRSA | Beta-lactam, linezolid, lipopeptide | 5 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 18 | 7 | Yes | No | No |

| 8 | N/A | E. faecalis | Vancomycin | 7 | Home IV antibiotic | 1 (1,500) | SD | 7 | 20 | Yes | No | No |

DBV: dalbavancin; IV: intravenous; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; N/A: not applicable; SD: single dose.

In the bacteraemia group, DBV was administered with the aim of continuing intravenous antibiotic therapy outside the hospital (n&#¿;=&#¿;8).

In all cases, DBV was administered on the day of discharge, either as a single dose or as a starting dose. The results of the reason for DBV use are shown in Fig. 2.

EffectivenessClinical and microbiological cure was documented in 84% of patients treated with DBV (n&#¿;=&#¿;21); 76.4% in the IE group (n&#¿;=&#¿;13) and 100% in the bacteraemia group (n&#¿;=&#¿;8). The mean follow-up time was 18.8 months (range: 1–64; SD 18.08) in the IE group and 15 months (range: 2–36; SD 11.73) in the bacteraemia group.

Treatment failure with DBV was documented in four patients. The first case was an 82-year-old man with recurrent IE with a prosthetic valve secondary to persistent S. aureus bacteraemia who required valve replacement, with DBV administered in an attempt to intensify microbicidal activity. The patient experienced a new episode of IE that again required valve replacement and a long-term change of antibiotic therapy to ciprofloxacin.

The second case was a 71-year-old male with IE with a metal prosthetic valve and pacemaker secondary to coagulase-negative Staphylococcus who developed systemic embolism, which required valve replacement, with DBV prescribed as consolidation therapy. However, the patient developed mediastinitis secondary to surgical wound infection that required reoperation on a second occasion to clean the surgical site. The patient's long-term antibiotic regimen was subsequently changed to ciprofloxacin and rifampicin.

The other two cases (IE on native valve and vascular graft infection) were patients with criteria for surgery but considered non-surgical candidates due to comorbidities, who received chronic antibiotic therapy with DBV on a compassionate use basis and eventually died.

There was evidence of reinfection after treatment with DBV in two patients. The first case was an 81-year-old woman with prosthetic IE and pacemaker infection secondary to Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteraemia of cutaneous focus. She was treated with DBV and rifampicin and was cured. Eighteen months later, she presented with a new episode of similar characteristics secondary to S. epidermidis bacteraemia with cutaneous entry. Valve and pacemaker replacement was decided upon and she was treated with daptomycin and rifampicin.

The second case was a 41-year-old woman with parenteral drug addiction who experienced a first episode of E. faecalis endocarditis. DBV was administered on an outpatient basis due to non-adherence and cure was achieved. Seven months later, she was admitted for a new episode of IE. Valve replacement and treatment with ceftriaxone was decided upon but she was lost to follow-up after requesting voluntary discharge.

Two patients with vascular catheter infection required prolonged antibiotic therapy (>20 days) prior to DBV treatment, as these were complicated bacteraemias. The first case was a patient with persistent bacteraemia despite intravenous antibiotic therapy (vancomycin/tigecycline). In the second, the bacteraemia was secondary to a surgical wound infection that required outpatient management through the home hospitalisation unit with different antibiotic regimens (ertapenem/linezolid). Both patients were cured after treatment with DBV.

Adverse effectsNo adverse effects associated with DBV administration were documented.

DiscussionDBV is an antibiotic approved for the treatment of SSTIs in adults and children older than 3 months.7,8 Its use in other clinical indications has been documented in animal models15 and clinical case series.16–19

Cardiovascular infections in general, and IE in particular, are diseases that require long-term antibiotic therapy. In addition, the proportion of patients requiring surgery as part of treatment (either for valve replacement or cardiac implantable device replacement) accounts for up to 50–60% of IE cases.5,12 Currently, IE patients are older and have multiple comorbidities, including immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, valvular heart disease or the need for cardiac implantable devices. They are also more frail and have longer hospital admissions than younger patients. Consequently, the mean length of hospital stay of these patients has increased, and with it, the rates of medical complications and adverse effects from long-term antibiotic therapy.20 In addition, patients’ perceived quality of life and functional capacity are lower. In this clinical and epidemiological context, new molecules with antimicrobial activity and efficacy similar to current treatments, that are well tolerated and can be administered outside the hospital setting, could lead to a significant reduction in the costs associated with hospital stays as well as a reduction in the risks and complications associated with prolonged stays.

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of DBV allow it to be administered as a single dose weekly or every two weeks without losing antibiotic coverage, making it an attractive option that facilitates adequate adherence and compliance in prolonged therapies administered outside the hospital setting. In addition, DBV’s lack of significant interaction with cytochrome P450 activity21 reduces the possibility of drug interactions in typically polymedicated patients. A single dose of 1,500&#¿;mg, or 1,000&#¿;mg followed by 500&#¿;mg per week, is recommended for the treatment of SSTIs. However, in cardiovascular infection its dosage is more widely disputed, as it is a therapy used outside clinical guidelines.22 Treatment adherence problems in IE, especially in patients with parenteral drug addiction or alcoholism, is an added problem. Ajaka et al.19 describe the utility of DBV in this patient profile, concluding that it may have a useful role as rescue therapy in the treatment of IE and bacteraemia in a population with barriers to access to standard treatment. Social problems and lack of family support or domestic support are proven determinants of non-adherence to treatment. DBV could play a useful role in this regard, ensuring compliance thanks to its convenient dosage.

Moreover, compared to other outpatient treatment options for cardiovascular infection and IE in particular, DBV is an attractive treatment option. Other parenterally-administered molecules (oritavancin) have been studied for outpatient treatment of IE,23 but their role in terms of efficacy and safety in this type of infection has yet to be determined. In addition, a growing number of studies have shown favourable data on the treatment of IE with oral antibiotic therapy in the outpatient setting.20,24,25 Although the results thus far are promising, such a therapy modality should only be applied for the time being in selected patients and the same standards of clinical follow-up as in conventional inpatient therapy should be maintained. It is not just a matter of prescribing long-term outpatient therapy, but of ensuring adequate adherence and clinical monitoring of the patient. DBV, as a molecule available only for parenteral administration, not only ensures compliance, but also guarantees the opportunity for clinical follow-up each time the patient comes to the hospital setting to receive their weekly or fortnightly dose.

With regard to bacteraemia, it is interesting to note that in adults it has traditionally been treated with intravenous antibiotic therapy, with an increasing trend towards transition to oral antibiotic therapy. In fact, an Infectious Diseases Society of America expert panel considered the transition from parenteral to oral therapy appropriate in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive infections as long as the focus of infection was controlled and the patient was clinically stable.26 However, in patients with S. aureus bacteraemia, the majority were in favour of maintaining intravenous antibiotic therapy. DBV would meet this requirement by allowing outpatient treatment.

Our results are in line with the available evidence on the use of DBV in IE and bacteraemia, and indicate that it could be an optimal and safe alternative to in-hospital treatment in clinically stable patients who only require continued hospitalisation for the administration of antibiotic therapy and in whom adequate out-of-hospital follow-up can be guaranteed. In our study, all patients had received previous parenteral antibiotic therapy with different combinations of antibiotics, with DBV being used as consolidation therapy when the infection was controlled, both in the IE and bacteraemia patient groups. In this high-risk, complex and difficult-to-manage population, overall cure rates of more than 80% of those treated were achieved. These results are similar to those of other series published to date in both the IE16–19 and bacteraemia groups.27

In our study, several patients with IE required prolonged prior antibiotic therapy, with ranges as wide as seven to 730 days, and subsequent doses of DBV administered also varying widely (between one and 12 doses). This can be explained by the fact that these were patients with a high surgical risk in whom conservative treatment with long-term chronic antibiotic therapy was chosen to achieve cure. Subsequent switch to DBV was considered as suppressive antibiotic therapy when other in-hospital treatment options had been exhausted or when imaging tests (transoesophageal echocardiogram and PET/CT) showed evidence of progression of the infection. In this regard, there are several publications on the use of DBV as suppressive antibiotic therapy in both osteoarticular infection28–30 and cardiovascular infection.31 These cases would justify the high mean number of days of antibiotic pre-treatment in our series (80 days) compared to the usual IE mean.

It is striking that in the group of patients with bacteraemia in our series, mainly due to coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and generally related to catheter infection, DBV was administered after a prolonged period of previous conventional antibiotic therapy (two weeks). There were two reasons for this: 1) these were patients with persistent bacteraemia despite catheter removal, and 2) these were patients in whom it was impossible to remove the catheter as it was an indwelling device (Port-a-cath®, Hickman®) required for the administration of oncological therapy or parenteral nutrition.

The absence of adverse effects in our series is another positive aspect to take into account. Other therapeutic options commonly used in episodes of IE and/or Gram-positive cocci bacteraemia (vancomycin/linezolid) are associated with significant adverse effects (nephrotoxicity/haematological abnormalities)32 that increasingly limit their use in the elderly and polymedicated populations and in those with multiple comorbidities. It would also be a cost-effective treatment, helping to reduce the costs associated with hospitalisation for these infections. In this regard, the most recent data on the current mean length of hospital stay of IE patients in Spain, as well as the costs associated with hospitalisation, show the following results: the mean length of hospital stay for IE in surgically-treated patients is 40.1 days, while in medically-treated patients it is 23.1 days. The mean hospitalisation costs for IE are currently ;12,537 per patient, but there are huge differences between patients receiving surgery (;40,700/patient) and those receiving medical treatment alone (;9,257/patient).33–35 In this regard, a multicentre study conducted in different Spanish hospitals calculated a saving in length of hospital stay for IE of 557 days and 636 days for bacteraemia in those patients treated with DBV, concluding that it is a highly cost-effective drug.27 In our series, with a high proportion of patients undergoing surgery, the mean length of hospital stay was reduced by 4.7 days compared to the average (35.4 vs 40.1 days). Although our study does not include a direct cost-effectiveness analysis, treatment with DBV would reduce hospital admission costs in this highly complex patient profile with prolonged hospital stays.

Our study suffers from the limitations inherent in its retrospective design and small sample size, as well as the absence of a comparison group. All patients received DBV as consolidation therapy whether they were IE or bacteraemia patients, so we cannot provide scientific evidence for the evaluation of its efficacy and safety as first-line therapy in cardiovascular infection.

Moreover, since DBV belongs to the group of long-acting antibiotics and are relatively new molecules, their label indications are often not consistent with their use in real life. This results in a wide variety of DBV doses (500, 1,000 or 1,500&#¿;mg) and dosage (weekly, fortnightly), which makes it difficult to interpret the results. Pharmacokinetic studies are needed to identify the most appropriate dose in prolonged therapy.

Strengths of our study include the different types of cardiovascular infection represented. In contrast to other series that only evaluate the role of DBV in IE,17,19 our study presents two distinct patient groups with cardiovascular infection: 1) patients with IE on native valve, prosthetic valve or vascular device infection; and 2) patients with catheter-related and non-catheter-related bacteraemia, which brings novel aspects to findings published to date in the literature,36,37 as well as including a high proportion (48%) of patients undergoing surgery (n&#¿;=&#¿;12) in the IE group.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the long study period of our series (seven years), which is longer than other larger but shorter retrospective series, with study periods of two years.16,27

ConclusionsIn our study of patients with cardiovascular infection, DBV was found to be an effective drug as consolidation antibiotic therapy in both IE and bacteraemia patients.

The absence of adverse effects and interactions positions DBV as a safe therapy in polymedicated patients with a cardiovascular infection and comorbidities.

Its administration in the outpatient setting may contribute to the therapeutic management of patients with IE and bacteraemia caused by Gram-positive microorganisms.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.