GESIDA and the AIDS National Plan panel of experts suggest preferred (PR), alternative (AR), and other regimens (OR) for antiretroviral treatment (ART) as initial therapy in HIV-infected patients for the year 2016. The objective of this study is to evaluate the costs and the efficacy of initiating treatment with these regimens.

MethodsEconomic assessment of costs and efficiency (cost/efficacy) based on decision tree analyses. Efficacy was defined as the probability of reporting a viral load <50copies/mL at week 48 in an intention-to-treat analysis. Cost of initiating treatment with an ART regimen was defined as the costs of ART and its consequences (adverse effects, changes of ART regimen, and drug resistance studies) during the first 48 weeks. The payer perspective (National Health System) was applied, only taking into account differential direct costs: ART (official prices), management of adverse effects, studies of resistance, and HLA B*5701 testing. The setting is Spain and the costs correspond to those of 2016. A sensitivity deterministic analysis was conducted, building three scenarios for each regimen: base case, most favourable, and least favourable.

ResultsIn the base case scenario, the cost of initiating treatment ranges from 4663 Euros for 3TC+LPV/r (OR) to 10,894 Euros for TDF/FTC+RAL (PR). The efficacy varies from 0.66 for ABC/3TC+ATV/r (AR) and ABC/3TC+LPV/r (OR), to 0.89 for TDF/FTC+DTG (PR) and TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI (AR). The efficiency, in terms of cost/efficacy, ranges from 5280 to 12,836 Euros per responder at 48 weeks, for 3TC+LPV/r (OR), and RAL+DRV/r (OR), respectively.

ConclusionDespite the overall most efficient regimen being 3TC+LPV/r (OR), among the PR and AR, the most efficient regimen was ABC/3TC/DTG (PR). Among the AR regimes, the most efficient was TDF/FTC/RPV.

El panel de expertos de GESIDA/Plan Nacional del Sida ha recomendado pautas preferentes (PP), pautas alternativas (PA) y otras pautas (OP) para el tratamiento antirretroviral (TARV) como terapia de inicio en pacientes infectados por VIH para 2016. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar los costes y la eficiencia de iniciar tratamiento con estas pautas.

MétodosEvaluación económica de costes y eficiencia (coste/eficacia) mediante construcción de árboles de decisión. Se definió eficacia como la probabilidad de tener carga viral <50copias/ml en la semana 48 en análisis por intención de tratar. Se definió coste de iniciar tratamiento con una pauta como los costes del TARV y de todas sus consecuencias (efectos adversos, cambios de pauta y estudio de resistencias) que se producen en las siguientes 48 semanas. Se utilizó la perspectiva del Sistema Nacional de Salud, considerando solo costes directos diferenciales: TARV (a precio oficial), manejo de efectos adversos, estudios de resistencias y determinación de HLA B*5701. El ámbito es España, con costes de 2016. Se realizó análisis de sensibilidad determinista construyendo 3 escenarios para cada pauta: basal, más favourable y más desfavorable.

ResultadosEn el escenario basal, los costes de iniciar tratamiento oscilaron entre 4.663euros para 3TC+LPV/r (OP) y 10.894euros para TDF/FTC+RAL (PP). La eficacia osciló entre 0,66 para ABC/3TC+ATV/r (PA) y ABC/3TC+LPV/r (OP), y 0,89 para TDF/FTC+DTG (PP) y TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI (PA). La eficiencia, en términos de coste/eficacia, osciló entre 5.280 y 12.836euros por respondedor a las 48 semanas, para 3TC+LPV/r (OP) y RAL+DRV/r (OP), respectivamente.

ConclusiónAunque globalmente la pauta más eficiente fue 3TC+LPV/r (OP), considerando solamente las PP y las PA, la pauta más eficiente fue ABC/3TC/DTG (PP). De las PA, la más eficiente fue TDF/FTC/RPV.

Antiretroviral treatment (ART) has changed the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease's natural course,1,2 and has made it possible for patients’ life expectancy to approach that of the general population.3,4 ART is usually based on a three-drug approach with the goal of lowering the plasma viral load to undetectable levels, i.e., below a threshold of less than 50 copies/mL, and keep it suppressed as long as possible. In most cases, current ART regimens lead to a partial restoration of the immune system, both in quantity and quality, depending in part on the degree of baseline immunodeficiency levels.5–8 Thus, as a whole, ART is considered one of the top medical interventions in medical history in terms of cost/efficacy ratios, including developing countries.9–16

Expert panels from the AIDS Study Group (GESIDA for its Spanish acronym) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC for its Spanish acronym) and the (Spanish) AIDS National Plan (PNS for its Spanish acronym) have issued their 2016 treatment guidelines. Their recommendations include 4 preferred regimens (PR), 7 alternative regimens (AR), and 8 referred as other regimens (OR) according to the scientific evidence from randomized clinical trials (RCT) and the expert panel's opinion.17 However, in the context of limited resources any therapeutic intervention must be applied efficiently. Thus, both costs incurred and outcomes obtained by the different ART must be examined to identify the most efficient regimens within those recommended by the GESIDA/PNS guidelines. There are other costs to consider, in addition to the drugs, including those incurred while managing adverse effects (AE) or the costs of drug-resistance studies, among others. Studies published between 2011 and 2015 evaluated the efficiency of ART recommended regimens by GESIDA/PNS.18–22 Regimens recommended for 2016 differ from those recommended in previous years. In addition, new scientific evidence and changes in costs suggest the appropriateness of a new and updated economic evaluation of the current ART recommendations.

Consequently, the need for this new cost evaluation arose. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the costs and the efficiency (cost/efficacy) of the ART regimens proposed by the GESIDA/PNS 2016 guidelines as recommended initial therapies for HIV-infected patients who have not received previous ART, i.e., treatment-naïve patients.

MethodsThe first step was to form a scientific committee (SC) of 16 Spanish experts identified by GESIDA (this paper's authors except AJB and PL) with experience in the clinical management of HIV-infected patients. SC's tasks included providing general advice, validating the assumptions made as part of the economic evaluation, supplying the RCTs used as scientific evidence, and providing expert opinion when the scientific evidence was insufficient.

DesignEconomic assessment of the costs and efficiency (cost/efficacy) by building decision trees with deterministic sensitivity analysis. The decision trees were built for the calculation of costs, efficacy, and efficiency for each of the regimens recommended by GESIDA/PNS (Table 1). The analysis was performed from the payer's perspective: the Spanish National Health System (NHS) and, thus, only direct costs were considered. The setting is Spain and the model's time horizon is 48 weeks. This work is a cost and cost/efficacy analysis because ART outcomes are based on RCT findings (efficacy).

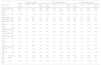

Regimens included in the evaluation, clinical trials used in the models, and regimen costs.

| Regimen | Dose (mg/day) | Trials | Costa (Euros) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABC/3TC/DTG (PR) | 600/300/50 | SINGLE,43 FLAMINGO,48 SPRING-244,45 | 6788 |

| TDF/FTC+DTG (PR) | 300/200+50 | FLAMINGO,48 SPRING-244,45 | 9177 |

| TDF/FTC+RAL (PR) | 300/200+800 | STARTMRK,49 QDMRK,d,36 SPRING-2,44,45 ACTG 525751 | 10,916 |

| TDF/FTC/RPV (AR) | 245/200/25 | ECHO,35 STAR46,47 | 6765 |

| TDF/FTC/EFV (AR) | 300/200/600 | STARTMRK,49 GS-934,26 ECHO,35 ACTG 5202,39 GS-US-236-0102,40 SINGLE,43 STAR46,47 | 6515 |

| TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI (AR) | 245/200/150/150 | GS-US-236-0102,40 GS-US-236-0103,41 WAVES,53 GS-US-292-0104/011154 | 9072 |

| ABC/3TC+RAL (AR) | 600/300+800 | SPRING-244,45 | 9556 |

| TDF/FTC+DRV/r (AR) | 300/200+800/100 | ARTEMIS,27 FLAMINGO,48 ACTG 5257,51 NEAT001/ANRS14352 | 8861 |

| TDF/FTC+ATV/r (AR) | 300/200+300/100 | CASTLE,28 ARTEN,29 ACTG 5202,39 GS-US-236-0103,41 GS-US-216-011442 ACTG 5257,51 WAVES53 | 8872 |

| ABC/3TC+ATV/r (AR) | 600/300+300/100 | ACTG 520239 | 7512 |

| ABC/3TC+EFV (OR) | 600/300+600 | CNA30024,34 ACTG 520239 | 5015b |

| TDF/FTC+NVP (OR) | 300/200+400 | ARTEN29, VERxVE37 | 5698c |

| ABC/3TC+DRV/r (OR) | 600/300+800/100 | FLAMINGO48 | 7501 |

| TDF/FTC+LPV/r (OR) | 300/200+800/200 | ARTEMIS,27 ABT730,30 CASTLE,28 GEMINI,31 HEAT,32 PROGRESS38 | 8402 |

| ABC/3TC+LPV/r (OR) | 600/300+800/200 | KLEAN,33 HEAT32 | 7042 |

| 3TC+LPV/r (OR) | 300+800/200 | GARDEL50 | 4610 |

| RAL+DRV/r (OR) | 800+800/100 | NEAT001/ANRS14352 | 10,732 |

| RAL+LPV/r (OR) | 800+800/200 | PROGRESS38 | 10,273 |

ABC: abacavir; ATV: atazanavir; COBI: cobicistat; DRV: darunavir; DTG: dolutegravir;EFV: efavirenz; EVG: elvitegravir; FTC: emtricitabine; LPV: lopinavir; NVP: nevirapine;/r: ritonavir-boosted; RAL: raltegravir; RPV: rilpivirine; TDF: tenofovir DF; 3TC: lamivudine.

PR: Regimen designated as “Preferred” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2015 AIDS National Plan.18

AR: Regimen designated as “Alternative” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2015 AIDS National Plan.18

OR: Regimen designated as “Other” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2015 AIDS National Plan.18

The cost is the same when ritonavir is replaced by cobicistat.

Cost at 48 weeks, laboratory sale price (LSP) plus 4% VAT minus the 7.5% obligatory reduction, based on the combinations Triumeq®, Atripla®, Truvada®, Kivexa®, Eviplera® and Stribild®.18

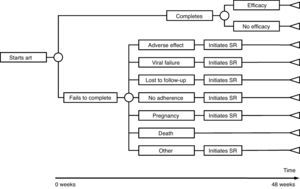

The model of economic analysis consists of as many decision trees as recommended regimens. Each decision tree was built based on the data from the RCTs assessing the corresponding regimen and it reproduces the regimen's characteristics in terms of efficacy, AE, and reasons for withdrawal (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Sources providing data on efficacy, AE, and withdrawalsThe SC provided the studies reporting the RCT data potentially useful for the economic assessment of the different regimens evaluated. To be included, the RCTs had to: (1) assess at least one of the regimens under evaluation; (2) provide or allow the calculation of the proportion of patients with undetectable viral loads (<50 copies/mL) at 48 weeks; (3) follow patients for at least 48 weeks; (4) report patient withdrawal rates and reasons; and (5) report AE. Studies found eligible were included as source of scientific evidence for the model.

Sources of information in the absence of scientific evidence: the use of expert opinionWhen scientific evidence on certain needed variables was not available, the SC expert opinion was used. Two investigators (PL and AJB) elaborated data collection sheets for the variables of interest. These sheets were then sent to each expert. To assure that the experts’ responses were independent from each other, contact among SC members was not allowed. Regarding continuous variables (e.g., duration in days of an itching episode, or number of visits to a specialist in case of renal failure), the mean of the experts’ estimates was calculated. For dichotomous variables (e.g., a serious/moderate AE is or not ART-related, or is chronic or with isolated occurrence) the majority opinion was chosen. The resulting summary estimates were reviewed and approved by all SC members.

Efficacy definition and measurementEfficacy was defined as the quotient of the number of patients with undetectable viral load at week 48 post-ART (i.e., responders) (numerator) and the number of patients initiated on ART (denominator). Efficacy was estimated based on an intention-to-treat analysis of the exposed (“Intent-to-treat exposed” [ITT-E]) and missing or incomplete follow-ups were designated as failures (“missing or non-completer=failure”). Although this may not have been one of the main endpoints in the RCTs examined, it could be calculated from all studies under review. In the event that more than one RCT assessed the same regimen, efficacy was calculated as the quotient of the sum of responders (numerator) and the sum of patients initiated on ART in the RCTs (denominator).

Definition and calculation of costsBased on a payer's perspective, this study considers only direct costs, i.e., the use of NHS resources. Within these costs, however, only differential costs are taken into account, i.e., non-identical costs across all regimens under study: ART, AE management, genotypic study of drug resistance, and HLA B*5701 testing. Direct costs were calculated multiplying the amount of resources used by the unit cost of each resource. The cost of initiating a regimen comprises the cost of ART and all the consequences (e.g., AE or need to switch regimens) incurred in 48 weeks due to the decision of initiating ART with that regimen.

Use of resourcesARTPatients completing treatment during the trial are assigned the costs of 48 weeks of the initial regimen. For those who do not complete the treatment, it was assumed that the initial regimen was discontinued at 24 weeks, on average. Thus, they are assigned the costs of 24 weeks of the initial regimen plus the costs of 24 weeks of the substitution regimen. Each substitution regimen was chosen based on the reason for discontinuation of the initial regimen, according to the opinion of the experts (Table 2).

Substitution regimens for each initial regimen by reason for change (scientific committee consensus).

| Substitution regimens for each initial regimen and reason for switching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial regimen | Viral failure | Pregnancy | Adverse effect | Lost to follow-up | Lack of adherence | Other |

| 1. ABC/3TC/DTG | 8 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. TDF/FTC+DTG | 8 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3. TDF/FTC+RAL | 8 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| 4. TDF/FTC/RPV | 8 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 5. TDF/FTC/EFV | 8 | 14 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 5 |

| 6. TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI | 8 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 6 |

| 7. ABC/3TC+RAL | 8 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| 8. TDF/FTC+DRV/r | 17 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 9. TDF/FTC+ATV/r | 17 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 9 |

| 10. ABC/3TC+ATV/r | 2 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 10 |

| 11. ABC/3TC+EFV | 8 | 15 | 4 | 11 | 4 | 11 |

| 12. TDF/FTC+NVP | 8 | 12 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| 13. ABC/3TC+DRV/r | 2 | 13 | 4 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| 14. TDF/FTC+LPV/r | 8 | 14 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 14 |

| 15. ABC/3TC+LPV/r | 2 | 15 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 15 |

| 16. 3TC+LPV/r | 8 | 16 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 16 |

| 17. RAL+DRV/r | 8 | 17 | 4 | 17 | 8 | 17 |

| 18. RAL+LPV/r | 8 | 14 | 4 | 18 | 4 | 18 |

ABC: abacavir; ATV: atazanavir; COBI: cobicistat; DRV: darunavir; DTG: dolutegravir; EFV: efavirenz; EVG: elvitegravir; FTC: emtricitabine; LPV: lopinavir; NVP: nevirapine; /r: ritonavir-boosted; RAL: raltegravir; RPV: rilpivirine; TDF: tenofovir DF; 3TC: lamivudine.

AE were defined as those effects identified by the RCT as ART-related. When the RCT reported a list of AE without identifying the ART-related ones, the SC opinion was applied. Since RCTs usually report AE occurring in over 2% of patients under the treatments assessed, only these AE were considered. The AE were classified into chronic and isolated according to expert opinion. Chronic AE are those that last as long as the treatment (e.g., dyslipidemia), whereas isolated AE are those occurring sporadically (e.g., skin rash).

The resources considered for the management of EA have been: drug treatment, emergency room visits, additional visits to the HIV specialist and other specialists, diagnostic tests, and hospital admissions. To the patients completing treatment during the trial, the costs of managing the AE occurring within the 48 weeks of their initial regimen were assigned. For those who do not complete the treatment, and following the aforementioned assumptions, the costs of 24 weeks of AE management related to the initial regimen and 24 weeks of AE management related to the substitution regimen were assigned (Table 2). Further, because chronic AE were assumed to occur for half of ART duration on average, the cost allocated for chronic AE management corresponds to half the period the patient received the corresponding ART. Compared to the 2013 study, there were no new AE to be considered, thus, the use of resources are those estimated by the SC in the 2013 study.20

Genotypic study of drug resistance and HLA B*5701 testingGenotypic studies of drug resistance considered as differential costs include: (1) conventional drug resistance study (in case of virologic failure); and (2) integrase resistance study (when virologic failure occurs in a regimen containing an integrase inhibitor such as raltegravir [RAL] or elvitegravir [EVG]). When a regimen includes abacavir (ABC), HLA B*5701 testing was considered before initiating treatment.

Estimation of the unit costs of resources consideredARTThe cost of each ART was calculated according to the costs of the drugs involved. In the case of Spain, this means that regimen costs were calculated based on the laboratory sale price (LSP) plus 4% VAT minus the 7.5% reduction required by the Spanish government as one of the extraordinary measures to reduce public deficit (not applicable to generic drugs).23 Specifically, the following drugs were assigned the following prices: (1) the ABC and lamivudine (3TC) combination was priced as Kivexa®24; (2) the emtricitabine (FTC) and tenofovir DF (TDF) combination was priced as Truvada®24; (3) for the TDF/FTC/efavirenz (EFV) regimen, the price of Atripla®24 was applied; (4) the regimen comprised of TDF/FTC/rilpivirine (RPV) was priced as Eviplera®24; (5) for the regimen TDF/FTC/EVG/cobicistat (COBI) the price of Stribild®24 was applied; (6) darunavir (DRV) was priced as Prezista®24; (7) ritonavir (r) as Norvir®25; (8) atazanavir (ATV) as Reyataz®25; (9) RAL as Isentress®24; (10) lopinavir (LPV)/r as Kaletra®24: (11) dolutegravir (DTG) as Tivicay®24; (12) for nevirapine (NPV) the price of Viramune®25 (extended-release NVP) was applied; (13) ABC/3TC/DTG as Triumeq®24; and (14) for EFV and 3TC the price of the corresponding generic drug was used.25 Since the price of ritonavir and COBI is the same, the regimens that may use ritonavir or COBI as farmacoenhancer have the same cost. The price of the regimen tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)/FTC/EVG/COBI or Genvoya®, one of the PR17 was not available when the calculations were done, for this reason, this regimen is not considered in the analysis. With these prices, the 48 weeks of treatment cost for each regimen is shown in Table 1.

AE-related costsThe costs of the drugs used to manage AE were estimated based on the drugs’ retail price plus VAT.25 When more than one commercial preparation was available, the least expensive one was chosen. The costs of other resources involved in AE management (emergency room visits, additional visits to the HIV specialist, visits to other specialists, diagnostic tests, and hospital admissions) were averaged due to regional variations. In Spain, the health care provision is decentralized at the level of the Autonomous Communities (AC), thus, prices vary by AC. Resources were priced using the official fees in each AC. The cost of each unit of resource was estimated as the average of the prices officially applied to third parties responsible for payment, or to patients not eligible for coverage, of health care services offered by the Departments of Health of each AC (Table 3).

Unit cost of resources.

| Resource | Euros | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Drug resistance studies | ||

| Conventional | 328.00 | Study |

| Integrase | 328.00 | Study |

| HLA B*5701 | 151.00 | Test |

| Visit to specialist | ||

| First visit | 145.37 | Visit |

| Following visits | 85.95 | Visit |

| Emergency room | ||

| Emergency room visit | 189.70 | Visit |

| Hospitalization | ||

| Hospital ward admission | 551.74 | Day |

| Diagnostics | ||

| Ultrasound | 75.11 | Unit |

| Routine blood work | 42.78 | Unit |

| Transaminases | 12.63 | Unit |

| Coagulation | 7.74 | Unit |

| Stool culture | 32.76 | Unit |

| Insulinaemia | 10.20 | Unit |

| Glycemic curve | 31.14 | Unit |

| Treatments | ||

| Atorvastatine | 0.16 | 10mg |

| Bezafibrate | 0.32 | 400mg |

| Glibenclamide | 0.02 | 5mg |

| Insuline | 9.76 | 300U |

| Paracetamol | 0.03 | 500mg |

| Lormetazepam | 0.07 | 1mg |

| Metoclopramide | 0.22 | 10mg |

| Loperamide | 0.30 | 2mg |

| Loratadine | 0.16 | 10mg |

| Prednisone | 0.08 | 10mg |

Due to lack of official data on the costs of drug resistance studies and HLA B*5701 testing, the costs provided by the Clinic Hospital of Barcelona were used (Table 3). HLA B*5701 testing is considered amortized in 5 years, thus, first year's amortization is 20%.

Definition and calculation of efficiencyEfficiency (cost/efficacy) for each regimen was calculated as the quotient of the cost of initiating treatment with that regimen (numerator) and efficacy (denominator). The result represents the cost of achieving a responder by week 48. The most efficient regimen (least cost per responder) among the PR and AR was assigned an efficiency of 1, respect to which the relative efficiency of the rest of the regimens was calculated, being the regimens with small values in the relative efficiency more efficient than those with high values.

Sensitivity analysisDeterministic sensitivity analysis was performed for each of the models to take into account the underlying uncertainty on efficacy, AE, and costs estimators. These analyses provide the potential range within which the cost/efficacy ratios for each ART regimen would be. To this end, three scenarios were created: base case, most favourable, and least favourable for each initial ART regimen. The base case scenario is defined as the ratio of the central cost estimator (numerator) and the central efficacy estimator (denominator). The most favourable scenario is defined similarly where the numerator is the most favourable cost estimator and the denominator is the most favourable efficacy estimator. Finally, the least favourable scenario uses the least favourable estimators for both costs and efficacy for numerator and denominator, respectively.

The central cost estimator is calculated based on the central estimator of the AE probability and the average costs of AE management, drug resistance studies, and HLA B*5701 testing. The most favourable cost estimator is computed applying the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) lower limit of AE probability, and a 15% cut in the average costs of AE management, drug resistance studies, and HLA B*5701 testing. The least favourable cost estimator is computed applying the 95% CI upper limit of AE probability, and an additional 15% over the average costs of AE management, drug resistance studies, and HLA B*5701 testing. All scenarios include the same cost for each ART regimen since those costs do not involve any uncertainty. Finally, the 95% CI upper and lower limits are used to calculate the most and least favourable estimators of efficacy, respectively.

Software applicationSince local cost of a specific hospital may be different to the costs used in the model, a software application that facilitates the assignment of local costs was designed for allowing the calculation of ART costs, regimen initiation costs, efficiency (cost/efficacy), and relative efficiency of initiating treatment with the different regimens at each individual hospital setting. The application is available free of charge at http://www.gesida-seimc.org/guias_clinicas.php?mn_MP=406&mn_MS=407 or at https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/35731022/coste-eficacia-2016/Aplicaci%C3%B3n-TARV-VIH-GESIDA-2016.exe.

ResultsThe 25 RCTs included in the 2015 study22 were: GS-934,26 ARTEMIS,27 CASTLE,28 ARTEN,29 ABT730,30 GEMINI,31 HEAT,32 KLEAN,33 CNA30024,34 ECHO,35 QDMRK,36 VERxVE,37 PROGRESS,38 ACTG5202,39 GS-US-236-0102,40 GS-US-236-0103,41 GS-US-216-0114,42 SINGLE,43 SPRING-2,44,45 STAR,46,47 FLAMINGO,48 STARTMRK,49 GARDEL,50 ACTG5257,51 and NEAT001/ANRS143.52 These two last articles provide information on outcomes and AE for the week 96. Since our analyses have a time horizon of 48 weeks, we requested the 48 weeks data to the authors. In both cases, formally and confidentially, the authors sent to us the required data. In addition, the SC selected three additional RCTs that evaluate the efficacy of regimens recommended in the 2016 GESIDA/PNS consensus paper17: WAVES,53 GS-US-292-0104/0111,54 and ENCORE 1.55 From these studies, the ENCORE 155 does not meet one of the inclusion criteria (results at 48 weeks are not described). Finally, with the available scientific evidence, the 18 recommended regimens could be evaluated (Table 1). For regimens that may use ritonavir or COBI as farmacoenhancer, the efficacy and safety of ritonavir and COBI were considered the same.42

Costs of the ART regimens at 48 weeks varied between 4610 and 10,916 Euros, for 3TC+LPV/r (OR) and TDF/FTC+RAL (PR), respectively (Table 1, Fig. 2B). The cost of initiating ART, in the base case scenario, varied between 4663 Euros for 3TC+LPV/r (OR) and 10,894 Euros for TDF/FTC+RAL (PR). Within the most favourable scenario, costs varied between 4638 and 10,888 Euros for 3TC+LPV/r (OR) and TDF/FTC+RAL (PR), respectively. Within the least favourable scenario, costs fluctuated between 4692 and 10,904 Euros for 3TC+LPV/r (OR) and TDF/FTC+RAL (PR) (Table 4 and Fig. 2A and B).

Representation of the base case scenario. (A) Cost: cost of initiating a regimen including all potential consequences of initiating ART with that regimen (Adverse effects [AE] and changes to other regimens) that may occur within 48 weeks. Efficacy: proportion of patients with undetectable plasma viral load (<50copies of RNA of HIV/mL) at 48 weeks. The slope between the y-intercept and the coordinates for each regimen represents the efficiency (cost/efficacy). The slope reflects the cost of achieving one responder by week 48 from the payer perspective: the National Health Service (NHS). (B) ART Cost: Drug costs for each regimen for 48 weeks (laboratory sale price (LSP)+4% VAT – 7.5% reduction). Cost of initiating ART: cost of initiating a regimen including all potential consequences of initiating ART with that regimen (Adverse effects [AE] and changes to other regimens) that may occur within 48 weeks. Cost per Responder: Cost of achieving one responder (<50copies of RNA of HIV per mL of plasma) by week 48 from the payer (NHS) perspective, calculated as the cost of initiating ART divided by its efficacy. ABC: abacavir; ATV: atazanavir; COBI: cobicistat; DRV: darunavir; DTG: dolutegravir; EFV: efavirenz; EVG: elvitegravir; FTC: emtricitabine; LPV: lopinavir; NVP: nevirapine;/r: ritonavir-boosted; RAL: raltegravir; RPV: rilpivirine; TDF: tenofovir DF; 3TC: lamivudine. PR: Regimen designated as “Preferred” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17 AR: Regimen designated as “Alternative” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17 OR: Regimen designated as “Other” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17

Cost, efficacy, efficiency (cost/efficacy) and relative efficiency of initiating treatment with each regimen (using regimen ABC/3TC+EFV as the reference). Sensitivity Analysis.

| Base case scenario | Most favourable scenario | Least favourable scenario | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial regimen | Costa (Euros) | Efficacy | C/Eb | Relative C/Ec | Costa (Euros) | Efficacy | C/Eb | Relative C/Ec | Costa (Euros) | Efficacy | C/Eb | Relative C/Ec |

| ABC/3TC/DTG (PR) | 6947 | 0.88 | 7929 | 1.000 | 6900 | 0.90 | 7657 | 1.000 | 7001 | 0.85 | 8226 | 1.000 |

| TDF/FTC+DTG (PR) | 9278 | 0.89 | 10,380 | 1.309 | 9239 | 0.92 | 10,001 | 1.306 | 9325 | 0.86 | 10,795 | 1.312 |

| TDF/FTC+RAL (PR) | 10,894 | 0.85 | 12,765 | 1.610 | 10,888 | 0.87 | 12,497 | 1.632 | 10,904 | 0.84 | 13,048 | 1.586 |

| TDF/FTC/RPV (AR) | 6910 | 0.84 | 8181 | 1.032 | 6874 | 0.87 | 7895 | 1.031 | 6949 | 0.82 | 8490 | 1.032 |

| TDF/FTC/EFV (AR) | 6648 | 0.80 | 8277 | 1.044 | 6618 | 0.82 | 8083 | 1.056 | 6682 | 0.79 | 8485 | 1.032 |

| TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI (AR) | 9182 | 0.89 | 10,297 | 1.299 | 9151 | 0.91 | 10,102 | 1.319 | 9218 | 0.88 | 10,503 | 1.277 |

| ABC/3TC+RAL (AR) | 9622 | 0.87 | 11,112 | 1.402 | 9591 | 0.92 | 10,447 | 1.364 | 9663 | 0.81 | 11,875 | 1.444 |

| TDF/FTC+DRV/r or DRV/COBI (AR)d | 8915 | 0.82 | 10,863 | 1.370 | 8897 | 0.84 | 10,591 | 1.383 | 8937 | 0.80 | 11,153 | 1.356 |

| TDF/FTC+ATV/r or ATV/COBI (AR)e | 8919 | 0.78 | 11,399 | 1.438 | 8900 | 0.80 | 11,153 | 1.457 | 8939 | 0.77 | 11,658 | 1.417 |

| ABC/3TC+ATV/r or ATV/COBI (AR)e | 7515 | 0.66 | 11,421 | 1.440 | 7511 | 0.70 | 10,710 | 1.399 | 7520 | 0.61 | 12,232 | 1.487 |

| ABC/3TC+EFV (OR) | 5127 | 0.68 | 7536 | 0.951 | 5092 | 0.71 | 7143 | 0.933 | 5168 | 0.65 | 7979 | 0.970 |

| TDF/FTC+NVP (OR) | 5803 | 0.73 | 7927 | 1.000 | 5789 | 0.75 | 7670 | 1.002 | 5817 | 0.71 | 8203 | 0.997 |

| ABC/3TC+DRV/r or DRV/COBI (OR) d | 7709 | 0.85 | 9069 | 1.144 | 7607 | 0.93 | 8195 | 1.070 | 7832 | 0.77 | 10,149 | 1.234 |

| TDF/FTC+LPV/r (OR) | 8385 | 0.75 | 11,235 | 1.417 | 8377 | 0.77 | 10,948 | 1.430 | 8396 | 0.73 | 11,539 | 1.403 |

| ABC/3TC+LPV/r (OR) | 7150 | 0.66 | 10,801 | 1.362 | 7119 | 0.70 | 10,242 | 1.338 | 7187 | 0.63 | 11,427 | 1.389 |

| 3TC+LPV/r (OR) | 4663 | 0.88 | 5280 | 0.666 | 4638 | 0.93 | 5008 | 0.654 | 4692 | 0.84 | 5585 | 0.679 |

| RAL+DRV/r (OR) | 10,723 | 0.84 | 12,836 | 1.619 | 10,719 | 0.87 | 12,297 | 1.606 | 10,730 | 0.80 | 13,427 | 1.632 |

| RAL+LPV/r (OR) | 10,261 | 0.81 | 12,639 | 1.594 | 10,254 | 0.89 | 11,547 | 1.508 | 10,276 | 0.74 | 13,968 | 1.698 |

ABC: abacavir; ATV: atazanavir; COBI: cobicistat; DRV: darunavir; DTG: dolutegravir; EFV: efavirenz; EVG: elvitegravir; FTC: emtricitabine; LPV: lopinavir; NVP: nevirapine; /r: ritonavir-boosted; RAL: raltegravir; RPV: rilpivirine; TDF: tenofovir DF; 3TC: lamivudine.

PR: Regimen designated as “Preferred” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2015 AIDS National Plan.18

AR: Regimen designated as “Alternative” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2015 AIDS National Plan.18

OR: Regimen designated as “Other” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2015 AIDS National Plan.18

Cost of initiating a regimen including all potential consequences of deciding to initiate ART with that regimen (adverse effects and changes to other regimens) that may occur within 48 weeks.

Efficiency or cost/efficacy. Cost (Euros) of achieving one responder for the NHS (<50copies of RNA of HIV per ml of plasma by week 48; ITT-E missing or NC=failure).

The efficacy in base case scenario ranged between 0.66 (66% response rate at 48 weeks) for ABC/3TC+LPV/r (OR) or ABC/3TC+ATV/r (AR), and 0.89 for TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI (AR) and TDF/FTC+DTG (PR). Within the most favourable scenario, the efficacy varied between 0.70 for ABC/3TC+ATV/r (AR) or ABC/3TC+LPV/r (OR) and 0.93 for ABC/3TC+DRV/r (OR) or 3TC+LPV/r (OR). The least favourable scenario shows a variation in efficacy ranging from 0.61 for ABC/3TC+ATV/r (AR) and 0.88 for TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI (AR) (Table 4 and Fig. 2A).

The efficiency (cost/efficacy), in the base case scenario varied between 5280 and 12,836 Euros per responder for 3TC+LPV/r (OR) and RAL+DRV/r (OR), respectively. The efficiency values in the most favourable scenario ranged between 5008 and 12,497 Euros per responder for 3TC+LPV/r (OR) and TDF/FTC+RAL (PR), respectively. Within the least favourable scenario these same estimates varied between 5585 and 13,968 Euros per responder for 3TC+LPV/r (OR) and RAL+LPV/r (OR), respectively. Among the PR and AR, the most efficient regimen, selected with a relative cost/efficacy of 1, was ABC/3TC/DTG (PR) with a cost per responder of 7929 Euros in the base case scenario. When initiating ART with the regimen TDF/FTC+RAL (AR), each responder was 61.0% more expensive than with the regimen ABC/3TC/DTG (PR) if using the base case scenario, 63.2% more expensive in the most favourable scenario, and 58.6% more expensive in the least favourable scenario

Considering all regimens, initiating ART with 3TC+LPV/r (OR), to obtain one responder was 33.3% less expensive than ABC/3TC/DTG (PR) if using the base case scenario, 34.6% less expensive in the most favourable scenario, and 32.1% less expensive in the least favourable scenario (Table 4 and Fig. 2A and B).

In the base case scenario, among the regimens containing non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, the least efficacious (68% of response rate), least expensive, and most efficient (cost per responder 7536 Euros) was ABC/3TC+EFV (OR), while TDF/FTC/RPV (AR) was the most efficacious (84% of response rate) and a little bit less efficient (cost per responder 8181 Euros). Among the regimens including PI/r, the most efficacious (88% of response rate), least expensive and most efficient (cost per responder 5280 Euros) was 3TC+LPV/r (OR), while the least efficient (cost per responder 12,836 Euros) was RAL+DRV/r (OR). Finally, among the regimens including integrase inhibitors, the most efficacious regimens (89% of response rate) were TDF/FTC+DTG (PR) and TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI (AR), while ABC/3TC/DTG (PR) was the most efficient (7929 Euros per responder) (Table 4 and Fig. 2A and B).

DiscussionThe GESIDA/PNS panel stratified the recommended regimens in PR, AR and OR according to reasons widely justified and discussed in the original report.17 Of the ten ART regimens recommended by GESIDA/PNS in their 2016 consensus paper17 as PR or AR for naïve patients considered in this analysis, TDF/FTC/EFV (AR) emerged as the least expensive whether considering the ART cost alone or considering all the additional costs derived from the decision of initiating treatment with an ART regimen (AE management, drug resistance tests, HLA B*5701 test, and regimen change), however, the most efficient was ABC/3TC/DTG (PR). Considering all the regimens, 3TC+LPV/r, classified as “other” by the GESIDA/PNS consensus group, was the least expensive, one of the most efficacious (88% of response rate) and the most efficient (5280 Euros per responder in the base case scenario). Some regimens present a high efficacy but are less efficient due to their high cost (e.g., TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI) while in others (e.g., ABC/3TC+ATV/r or ABC/3TC+LPV/r) the low efficiency is due to their low efficacy. Lack of experience, pill burden and toxicity issues in real clinical practice may be among the reasons why the GESIDA/PNS panel qualifies 3TC+LPV/r as OR despite being the less costly and the most efficient. The regimen TAF/FTC/EVG/COBI, one of four recommended as PR by GESIDA, has not been considered in the analysis. The reason is that the official price of the regimen in Spain was not available when the economic calculations were made. At the time of writing the manuscript, it is confirmed that the price is similar to the TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI combination. Since its tolerance is better and its effectiveness is equal or higher54 it could be foreseen that the cost-efficacy (efficiency) ratio will be good when next year is included in the analysis.

The cost of initiating a treatment with a regimen is the real costs to the NHS because it includes ART costs and the costs of the consequences (e.g., AE management or switching regimen); whereas for the hospital's pharmacy the cost consists of only the ART. The ratio cost/efficacy represents the NHS cost of achieving one responder, at 48 weeks in our case. In certain cases, the physician and/or the patient may prefer a triple therapy regimen based on a non-nucleoside, a PI/r, or an integrase inhibitor, or even a dual therapy, for clinical reasons or personal preferences. In such cases, the costs of initiating treatment, its efficacy, and the cost/efficacy ratio would have to be considered within each of these three regimen types56 and might not necessarily be the major driver in the decision making process.

For all regimens, the main cost of initiating treatment is the ART due to its high price. In contrast, the costs related to managing AE are low since only a very small percentage of patients present AE and the involved costs are low.

The study results should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. A potential limitation is that the analyses are based on RCTs performed in different countries, during different periods of time, with different inclusion and exclusion criteria, and even with different presentations for the same drug in regimens with LPV (capsules and pills) or NVP (normal formula or extended-release). Thus, results may have differed if all regimens had been administered in similar populations and time periods. In fact, more recent studies include lower percentages of patients with poor prognosis, i.e., those with low CD4 counts (<100/200 cells/μL) and elevated plasma viral load (>100,000 copies/mL). This leads to results with higher levels of efficacy than those reported in previous studies and may offer an advantage to drugs assessed recently for the first time. In addition, there are drugs with restricted use. For instance, NVP should only be initiated on women with CD4 <250cells/μL or on men with CD4 <400cells/μL. Also, RPV is only approved for individuals with baseline plasma viral loads <100,000copies/mL, and TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI is only approved for patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate >70ml/min. RPV efficacy results in patients with plasma viral load <100,000copies/mL are better than the average efficacy from the RCTs included in this analysis. However, these studies included patients similar to those participating in studies of the other drugs, thus, efficacy data refer to comparable patient groups.

Further, NVP studies reviewed (ARTEN29 and VERxVE37) included only patients with low CD4 counts (<250cells/μL in women and <400cells/μL in men) which may explain the poorer results regarding efficacy compared to other regimens. However, because those are the drug label's approved criteria, such trials were included in the analysis. Also, study ACTG 520239 did not provide AE data at 48 weeks, so AE data at 96 weeks were included instead under the assumption that most AE do occur during the first 48 weeks. Another limitation is that some RCTs do not to specify which AE were ART-related, such lack of information was completed with the experts’ opinion. Similarly, for lack of other scientific evidence, i.e., resources needed for AE management and the substitution regimens used when the initial regimen was suspended were estimated based on experts’ opinion. Additionally, although the study's methodology ensures agreement at a national level, calculations may differ in other countries. Finally, regimens’ efficacy was evaluated using the ITT-E analytical approach assigning missing or incomplete follow-ups as failures (“missing or non-completer=failure”). This method of evaluation may not coincide with the main end-point in some of the studies, though the data published in the reports do allow for the necessary calculations. In other words, results may have differed if other analytical methods of measuring efficacy had been used instead. Also, when more than one RCT assessed the same regimen, a metanalysis could not be performed because of the absence of a common comparator. Finally, another limitation would be that these findings are applicable only to Spain and taking into account the Spanish official drug prices in February 2016, not considering potential local discounts even when they could be substantial and not uncommon as in the case of RAL. Thus, results should be interpreted cautiously especially in environments where prices differ substantially from the Spanish average.

Major strengths of this study include the use of the best scientific evidence available and the sensitivity analyses performed to best capture the underlining uncertainty in costs and outcomes. Further, the models use efficacy estimators, with universal validity, which, added to the fact that the methodology is applicable to any environment, would make the results valid in other contexts as long as local costs could be entered into the models.

In order to facilitate the use of this methodology in other centres or countries with different ART- or HIV management-related costs or to take into account the potential future use of generic drugs,57 a software application was developed and made available free of charge at https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/35731022/coste-eficacia-2016/Aplicaci%C3%B3n-TARV-VIH-GESIDA-2016.exe or at http://www.gesida-seimc.org/guias_clinicas.php?mn_MP=406&mn_MS=407. This application allows the calculations of ART costs, initiating ART costs, efficiency (cost/efficacy), and the relative efficiency of initiating treatment with the different regimens based on local costs of the medicines and the management of side effects. This application will aid any centre interested in computing its own estimates based on the model developed here.

The ideal study design to determine ART efficiency in regular clinical practice would be a prospective cohort cost/effectiveness study with a long follow-up period, but these studies are unlikely to be carried out. When lacking such studies, cost/efficacy models provide a very useful tool to examine costs and ART efficiency based on the best scientific evidence available.

Current study findings are relevant because the mission of any health care system is to maximize the population's health outcomes in a context of inherently limited resources. In such context, guaranteeing the system's sustainability requires an efficient use of the limited resources.58,59

At the patient–physician level, the drug efficiency is an important characteristic of therapy but not necessary the most important driver when choosing an antiretroviral combination as initial therapy, because other features must be taken into consideration as efficacy, tolerability, safety, convenience, drug–drug interactions and resistance profile. So, the results should be interpreted by experts and the most efficient combination may not be the best one, or even may not be a “preferred” one, as it happens in this analysis. For this reason, periodic economic evaluation studies, such as this one, have the potential of facilitating the decision making process of health professionals, managers, and political decision-makers in the field of HIV-infection management.

Conflict of interestAntonio Rivero has received consultancy fees from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen and Roche Pharmaceuticals, and speaker fees from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Roche Pharmaceuticals.

José Antonio Pérez-Molina has received consultancy fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, ViiV Healthcare, and Gilead Sciences, and speaker fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, ViiV Healthcare, and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Antonio Javier Blasco has no potential conflicts of interest related to this study.

José Ramón Arribas receives advisory fees, speaker's fees, or grant support from Viiv Healthcare, Tibotec, Janssen, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Tobira.

Manuel Crespo has received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Janssen, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr Crespo has also received research grants from AbbVie, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare.

Pere Domingo has received honoraria for consultancy from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Janssen, and ViiV Healthcare. He has also received research grants (money for Institution) from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer Inc and ViiV Healthcare. He had also received honoraria for speech from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Domingo is recipient of a grant from the Programa de Intensificación from FIS in the year 2013 (INT12/383).

Vicente Estrada has received honoraria, speakers’ fees and/or funds for research from Abbvie, Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, ViiV Healthcare and Janssen.

José Antonio Iribarren has disclosed that he has served as an advisor or consultant for Abbvie, Gilead and Janssen; grant support from Abvvie, BMS, MSD, Basque Government, FIPSE and FISS, and support to attendance to conferences from Abbvie, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, MSD, and ViiV Healthcare.

Hernando Knobel has done consultancy work for Abbott Laboratories, Abbvie Laboratories, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme and ViiV Healthcare and has received compensation for lectures from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen and ViiV Healthcare.

Pablo Lázaro has no potential conflicts of interest related to this study.

José López-Aldeguer Jose López Aldeguer has received consultancy and speaker fees from Abbott Laboratories, ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Fernando Lozano has disclosed that he has served as an advisor or consultant for Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck-Sharp & Dohme, Roche Pharmaceuticals and ViiV Healthcare, and has also served on the speaker's bureaus for, as well as received support for educational activities from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche Pharmaceuticals and ViiV Healthcare.

Santiago Moreno has been involved in speaking activities and has received grants for research from Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Glaxo Smith Kline, Janssen Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, and Schering Plough.

Rosario Palacios receives advisory fees, speaker's fees, or grant support from Viiv Healthcare, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Juan Antonio Pineda has received honoraria as consultant for Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag and Merck Sharp & Dohme; has received grants for research from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myer Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche Pharma and ViiV Healthcare; and speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche Pharma and ViiV Healthcare.

Federico Pulido receives advisory fees, speaker's fees, or grant support from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Viiv Healthcare.

Rafael Rubio reports grants from Abbott and Janssen, and payment for lectures from Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, ViiV, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Javier de la Torre has received consultancy fees from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences, and speaker fees from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Roche Pharmaceuticals.

Montserrat Tuset has received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Janssen and speaker fees from Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and ViiV Healthcare.

Josep M. Gatell has received honoraria for speaking or participating in Advisory Boards and/or research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Tobira, Gilead, BI, Janssen, ViiV Healthcare and Abbvie.

Support and funding for this study come from Grupo de Estudio de SIDA (GESIDA), Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC) (AIDS Study Group, Spanish Society for Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology). The study benefited from the scientific sponsorship and support of the Red de Investigación en SIDA (AIDS Research Network) (RIS; RD06/0006 and RD12/0017).

We thank the NEAT001/ANRS143 study researchers Elizabeth C George, François Raffi, Christine Schwimmer, Abdel G Babiker, and Cédrick Wallet for providing us with unpublished data regarding the outcomes and adverse events at the 48 week without which the inclusion of the NEAT001/ANRS143 study would be impossible.

We thank the ACTG A5257 researchers Lumine H. Na, Jeffrey L. Lennox, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, and Heather J. Ribaudo for providing us with unpublished data regarding the outcomes and adverse events at the 48 week without which the inclusion of the ACTG A5257 study would be impossible.

![Representation of the base case scenario. (A) Cost: cost of initiating a regimen including all potential consequences of initiating ART with that regimen (Adverse effects [AE] and changes to other regimens) that may occur within 48 weeks. Efficacy: proportion of patients with undetectable plasma viral load (<50copies of RNA of HIV/mL) at 48 weeks. The slope between the y-intercept and the coordinates for each regimen represents the efficiency (cost/efficacy). The slope reflects the cost of achieving one responder by week 48 from the payer perspective: the National Health Service (NHS). (B) ART Cost: Drug costs for each regimen for 48 weeks (laboratory sale price (LSP)+4% VAT – 7.5% reduction). Cost of initiating ART: cost of initiating a regimen including all potential consequences of initiating ART with that regimen (Adverse effects [AE] and changes to other regimens) that may occur within 48 weeks. Cost per Responder: Cost of achieving one responder (<50copies of RNA of HIV per mL of plasma) by week 48 from the payer (NHS) perspective, calculated as the cost of initiating ART divided by its efficacy. ABC: abacavir; ATV: atazanavir; COBI: cobicistat; DRV: darunavir; DTG: dolutegravir; EFV: efavirenz; EVG: elvitegravir; FTC: emtricitabine; LPV: lopinavir; NVP: nevirapine;/r: ritonavir-boosted; RAL: raltegravir; RPV: rilpivirine; TDF: tenofovir DF; 3TC: lamivudine. PR: Regimen designated as “Preferred” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17 AR: Regimen designated as “Alternative” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17 OR: Regimen designated as “Other” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17 Representation of the base case scenario. (A) Cost: cost of initiating a regimen including all potential consequences of initiating ART with that regimen (Adverse effects [AE] and changes to other regimens) that may occur within 48 weeks. Efficacy: proportion of patients with undetectable plasma viral load (<50copies of RNA of HIV/mL) at 48 weeks. The slope between the y-intercept and the coordinates for each regimen represents the efficiency (cost/efficacy). The slope reflects the cost of achieving one responder by week 48 from the payer perspective: the National Health Service (NHS). (B) ART Cost: Drug costs for each regimen for 48 weeks (laboratory sale price (LSP)+4% VAT – 7.5% reduction). Cost of initiating ART: cost of initiating a regimen including all potential consequences of initiating ART with that regimen (Adverse effects [AE] and changes to other regimens) that may occur within 48 weeks. Cost per Responder: Cost of achieving one responder (<50copies of RNA of HIV per mL of plasma) by week 48 from the payer (NHS) perspective, calculated as the cost of initiating ART divided by its efficacy. ABC: abacavir; ATV: atazanavir; COBI: cobicistat; DRV: darunavir; DTG: dolutegravir; EFV: efavirenz; EVG: elvitegravir; FTC: emtricitabine; LPV: lopinavir; NVP: nevirapine;/r: ritonavir-boosted; RAL: raltegravir; RPV: rilpivirine; TDF: tenofovir DF; 3TC: lamivudine. PR: Regimen designated as “Preferred” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17 AR: Regimen designated as “Alternative” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17 OR: Regimen designated as “Other” by the expert panel of GESIDA and the 2016 AIDS National Plan.17](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/0213005X/0000003500000002/v1_201702210027/S0213005X16301598/v1_201702210027/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)