Carotenoid pigments have antioxidant properties beneficial for human health. Use of resonance Raman spectroscopy (RRS) as a reliable method for measuring carotenoid levels in tissues such as dermis has been suggested. However, data about the variability and reproducibility of this technique should be collected before it can be used.

ObjectiveTo assess reproducibility of RRS for detection of total β-carotene levels in the skin of Colombian adults.

DesignForty-eight healthy men and 30 healthy women with various pigmentation levels were enrolled into the study. Measurements by RRS were performed in the palmar region and medial and lateral aspects of the arms. Odds ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated, adjusting for confounding factors: body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, percent body fat, age, race, smoking, and sex. Reproducibility of the technique was estimated using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

ResultsMean β-carotene levels were 29.9±11.9 in men and 30.6±8.6 in women (p=0.787). No differences or significant associations were found of β-carotene levels with confounding factors assessed by sex. ICCs were 0.89 in the palmar region, 0.85 in the medial aspect of arm, and 0.82 in the external aspect of arm.

ConclusionRRS is a reliable method for non-invasive measurement of β-carotene levels in skin, and may be used as an important biomarker of antioxidant status in nutritional and health studies in humans.

Los pigmentos carotenoides poseen propiedades antioxidantes y beneficiosas para la salud de los seres humanos. Se ha sugerido la utilización de la espectroscopia de resonancia Raman (ERR) como un método fiable para su medición en tejidos como la dermis. No obstante, antes de poder utilizar esta técnica, es preciso recolectar datos sobre su variabilidad y reproducibilidad.

ObjetivoEvaluar la reproducibilidad de la técnica de ERR, para la detección de las concentraciones totales de β-carotenos en piel en adultos colombianos.

DiseñoUn total de 48 hombres y 30 mujeres saludables con diversos niveles de pigmentación fueron incluidos en el estudio. Se realizaron mediciones por ERR en región palmar, cara interna y externa de los brazos. Se calculó la odds ratio e intervalos de confianza del 95% ajustando por factores de confusión: índice de masa corporal, circunferencia de cintura, porcentaje de grasa corporal, edad, etnia, hábito de tabaquismo y sexo. La reproducibilidad de la técnica se estimó mediante el coeficiente de correlación intraclase (CCI).

ResultadosEl promedio de β-carotenos en hombres fue de 29,9±11,9 frente a 30,6±8,6 en mujeres (p=0,787). No se encontraron diferencias ni asociaciones significativas en los niveles de β-carotenos por los factores de confusión evaluados por sexo. Los CCI fueron: 0,89 en región palmar; 0,85 en cara interna de brazos, y 0,82 en cara externa de brazos.

ConclusiónLa EER constituye un método fiable para la medición no invasiva de las concentraciones de β-carotenos en piel y puede ser utilizado como un importante biomarcador del estatus antioxidante en estudios nutricionales y de salud en población humana.

Carotenoids are antioxidant molecules derived from plant pigments originally occurring in plants, animals, and bacteria, often highly oxygenated, or as chromoproteins, their prosthetic part.1 The carotenoids most commonly consumed in Western diets include α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin, and β-cryptoxanthin.2,3 Authors such as Krinsky et al.,4 Liu et al.,5 and Mayne et al.6 have shown that intake of carotenoid-rich diets is inversely related to the risk of chronic diseases, particularly certain types of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome.

However, several authors have questioned the validity of dietary surveys as indicators of dietary intake to objectively determine consumption of this significant antioxidant biomarker.5–7 In clinical and research settings, common carotenoids may be measured in blood and other tissues by biochemical methods after their extraction, and concentrations are known to correlate with dietary intake.5

To date, surveys of fruit and vegetable consumption have been based on carotenoid measurement in tissues using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). This is the gold standard procedure, but it has marked disadvantages. These include its high cost and methodological problems involving sample extraction, storage, processing, and testing, as well as many others.8 An additional disadvantage is the fluctuation in carotenoid levels in the different tissues in response to recent intake, particularly after the consumption of β-carotene and lycopene.9

RRS is a spectroscopic technique used in condensed matter physics and in chemistry to study the vibrational, rotational, and other low frequency modes in a system. RRS is based on the inelastic or Raman scatter of monochromatic light, usually coming from a laser. Carotenoids are molecules well adapted to light scatter by RRS, because they all have a strong absorption column in conjugated carbon chains (CC). In addition, in biological systems, RRS intensity is linearly related to carotenoid concentration.

Work by Ermakov et al.10,11 has shown the value and validity of RRS for non-invasive measurement of carotenoids in tissue such as skin. The Mayne et al. study6 in 28 healthy subjects showed total skin carotenoid levels, as measured by RRS, to be significantly correlated to total carotenoid levels measured by HPLC in skin biopsies (r=0.66; p=0.0001). Other authors have shown that β-carotene levels in skin correlate to dietary intake and plasma levels.12–14

The question of the β-carotene levels that can be considered as protective has recently prompted scientific research in primary prevention due to the involvement of this molecule in antioxidant status, a significant defense mechanism. Reliable, rapid, and non-invasive measurement of β-carotene levels would therefore provide information about individual health status.15 The purpose of this study was to assess the reproducibility of the RRS procedure for the detection of total β-carotene levels in the skin of Colombian adults.

Materials and methodsDuring the first six months of 2011, a descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted in 78 healthy subjects (n=48 males, n=30 females) aged 18 to 65 years from the northwest and metropolitan area of the city of Cali in Colombia. The sample was selected by advertising and sampling by intention. Subjects with a medical or clinical diagnosis of major systemic disease (including malignant conditions such as cancer), type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism, a history of drug or alcohol abuse, the use of multivitamin preparations, and inflammatory (trauma, contusions) or infectious conditions were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the ethics committee of the academic center approved the study in compliance with the ethical standards set out in the Declaration of Helsinki and the applicable legal regulations in Colombia governing research in humans (Decision 008430, of 1993, of the Colombian Ministry of Health). Participants who accepted and signed informed consent were given appointments to attend the laboratory of the Center for Research in Human Health and Performance and the Alférez Real Convention Center under fasting conditions for the procedures listed below.

β-carotene measurement using resonance Raman spectroscopySkin state was initially assessed in the palm of the hand and the medial and lateral aspects of the forearm. Carotenoids are known to concentrate in the palm of the hand, which was therefore the most obvious place for taking measurements. All other measurement sites were selected for their convenience for the reproducibility of the procedure.

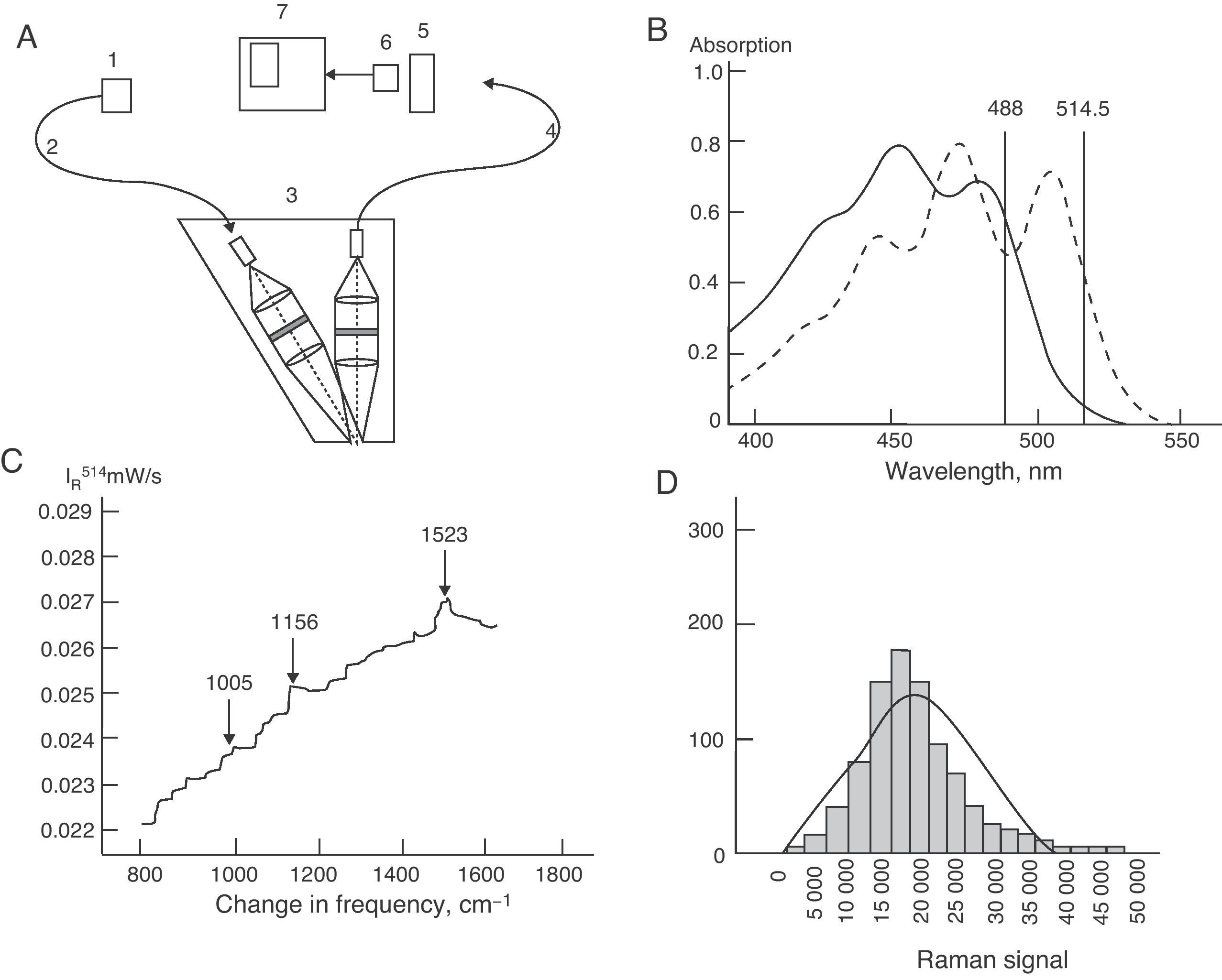

The participants were appointed to attend the clinic early in the morning after fasting. Details of in vivo measurement of β-carotene levels in human tissue using the RRS technique have been reported in other studies.11–15 To sum up, the instrument consists of a camera and several lines of argon laser in order to produce blue UV light at 488nm (Fig. 1A). Optical skin response is called Rayleigh scatter, and corresponds to the rigid and external morphology of dermal tissue (horny layer). The intensity of fluorescence of dual carboncarbon bonds (CC), called Raman intensity, is generated from a frequency change to 1524cm−1, being proportional to the number of total skin carotenoids (Fig. 1B and C). This technique uses a laser with a power<10mW and an exposure time of 15s, with an elliptic point size of 2mm×3mm14,15 (Pharmanex® BioPhotonic Scanner, USA). All measurements were taken in triplicate, and their mean was used for data analysis.

(A) Schematic representation of equipment for resonance Raman spectroscopy. 1: argon laser; 2, 4: optic fibers; 3: optic image acquisition system; 5: spectrograph; 6: camera; 7: computer. (B) Sample absorption spectra of two types of carotenoids: β-carotenes (solid line) and lycopenes (dotted line) in ethanol solution. (C) Typical Raman spectrum of β-carotenes obtained from in vivo readings in human dermis at 514.5nm using argon laser. (D) Bar chart of signal distribution by resonance Raman spectroscopy.

The following data were collected from each participant: family history of cardiovascular risk, personal history, nutritional 24-h recall, and anthropometric assessment, consisting of height, weight, and waist circumference using López et al. standardized procedures.16 Height was measured using a Krammer anthropometer (Holtain Ltd., Crymych Dyfed, United Kingdom) of 4 segments and a 1-mm precision. Weight was measured using floor scales (Health-o-Meter, Continental Scale Corp., Bridgeview, IL, USA) with a 500-g precision calibrated with known weights. These variables were used to calculate BMI in kg/m2. Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the iliac crests and lower costal margin using a plastic measuring tape with a precision of 0.5cm (Holtain Ltd., Crymych Dyfed, United Kingdom). Each participant was also asked to report his/her race and skin color (in the medial aspect of arm) under the guidance of the research assistant. The abovementioned measurements were taken using certified devices and according to standards of the international biological program prepared by the International Council of Scientific Unions, including the essential procedures for the biological study of human populations.17

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistical methods were used to estimate the distribution of RRS scores in the study population and the different subgroups. A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used for testing normal distribution of the study variables (Fig. 1D). Differences in binary variables were analyzed using a Student's t test, while a one-sided ANOVA test was used for multiple variables. An ICC was used to assess the reproducibility of measurements over time and in the three sites selected for measurement. ORs and 95% CIs adjusted for confounding factors including BMI, waist circumference, ethnicity, smoking, and sex were calculated. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association of dietary intake as determined by the 24-h recall questionnaire with skin levels of β-carotene by RRS. All statistical tests were performed using software SPSS 15.0 for Windows (Graphpad Instat, Graphpad Software, University of London, London, United Kingdom). A value of p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

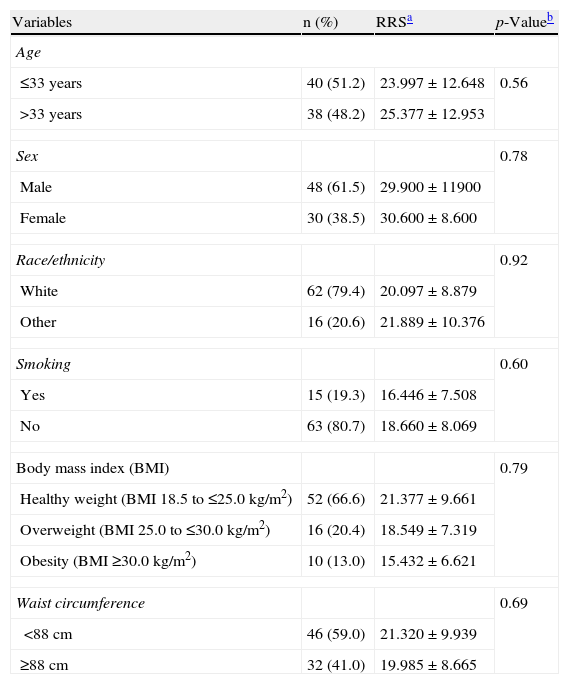

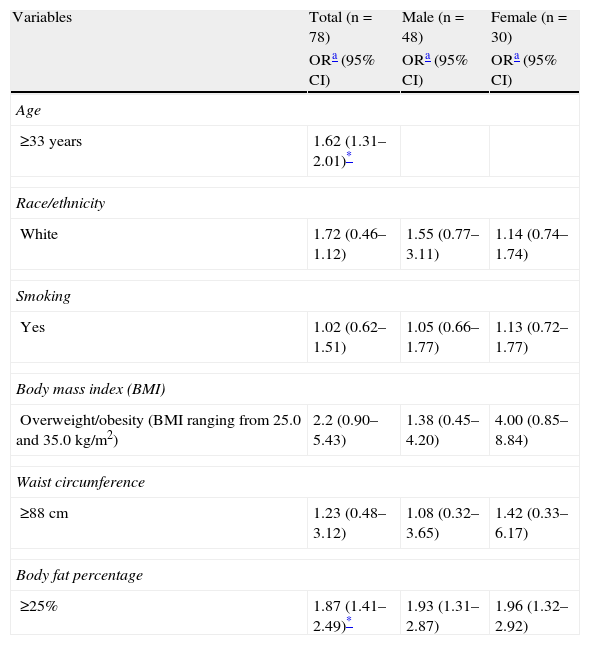

ResultsForty-eight healthy men and 30 healthy women with various pigmentation levels were enrolled into the study. Mean β-carotene levels were 29.900±11.900 in men and 30.600±8.600 in women (p=0.787). No significant differences or associations in β-carotene levels were found by confounding factors assessed by sex, except in the analysis of the general population for the variables of age≥33 years (OR=1.62; 95% CI=1.31–2.01; p<0.05) and percent fat increase ≥25% (OR=1.87; 95% CI=1.41–2.49; p<0.05) (Tables 1 and 2). No correlations were found either between dietary intake assessed using the 24-h recall questionnaire and β-carotene skin levels measured by RRS.

Total β-carotene levels by resonance Raman spectroscopy and clinical characteristics of the study population (n=78).

| Variables | n (%) | RRSa | p-Valueb |

| Age | |||

| ≤33 years | 40 (51.2) | 23.997±12.648 | 0.56 |

| >33 years | 38 (48.2) | 25.377±12.953 | |

| Sex | 0.78 | ||

| Male | 48 (61.5) | 29.900±11900 | |

| Female | 30 (38.5) | 30.600±8.600 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.92 | ||

| White | 62 (79.4) | 20.097±8.879 | |

| Other | 16 (20.6) | 21.889±10.376 | |

| Smoking | 0.60 | ||

| Yes | 15 (19.3) | 16.446±7.508 | |

| No | 63 (80.7) | 18.660±8.069 | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.79 | ||

| Healthy weight (BMI 18.5 to ≤25.0kg/m2) | 52 (66.6) | 21.377±9.661 | |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0 to ≤30.0kg/m2) | 16 (20.4) | 18.549±7.319 | |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30.0kg/m2) | 10 (13.0) | 15.432±6.621 | |

| Waist circumference | 0.69 | ||

| <88cm | 46 (59.0) | 21.320±9.939 | |

| ≥88cm | 32 (41.0) | 19.985±8.665 | |

Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals of having low total β-carotene levels by resonance Raman spectroscopy in the study population.

| Variables | Total (n=78) | Male (n=48) | Female (n=30) |

| ORa (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | |

| Age | |||

| ≥33 years | 1.62 (1.31–2.01)* | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.72 (0.46–1.12) | 1.55 (0.77–3.11) | 1.14 (0.74–1.74) |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 1.02 (0.62–1.51) | 1.05 (0.66–1.77) | 1.13 (0.72–1.77) |

| Body mass index (BMI) | |||

| Overweight/obesity (BMI ranging from 25.0 and 35.0kg/m2) | 2.2 (0.90–5.43) | 1.38 (0.45–4.20) | 4.00 (0.85–8.84) |

| Waist circumference | |||

| ≥88cm | 1.23 (0.48–3.12) | 1.08 (0.32–3.65) | 1.42 (0.33–6.17) |

| Body fat percentage | |||

| ≥25% | 1.87 (1.41–2.49)* | 1.93 (1.31–2.87) | 1.96 (1.32–2.92) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

The ICC of β-carotene skin levels in the three measurement sites used in this study (palm of the hand and medial and lateral aspects of the forearm) ranged from 0.82 to 0.87, suggesting a high reproducibility of the method. The highest ICC was found in the palm of the hand (ICC=0.87), followed by the medial forearm (ICC=0.85) and lateral forearm (ICC=0.82), showing that β-carotene levels were reproducible and consistent with the measurement time of each part of the body.

DiscussionThe main objective of this study was to assess the reproducibility of the RRS procedure for the detection of total β-carotene levels in the skin of Colombian adults. For years, the nutritional significance of carotenoids was mainly attributed to the fact that some of them have provitamin A activity, which continues to be studied.18,19 Interest in the isoprenoid compounds has greatly increased not only in Latin America,20–22 but also worldwide23,24 because of their antioxidant capacity25 and their potential benefits for the prevention of various diseases, including certain types of cancer26 and eye27 and vascular28 disorders.

Several authors29,30 have found lower plasma antioxidant levels in smokers. This is due to both the greater implication of available antioxidants in smoking-induced blockade of the free radical chain, and to a diet with a decreased content of these compounds. This study found no differences in statistically significant associations between β-carotene levels and smoking, in agreement with the findings reported by Farchi et al.31 These authors analyzed the effect of tobacco smoke with intake of α- and β-carotenes, ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol, and lycopenes in 1249 smokers of both sexes. No associations were found either between smoking and fruit and vegetable intake, which also agree with studies by Zondervan et al.29 and Marangon et al.30 By contrast, Rodriguez-Castilla et al.32 showed in male smokers with characteristics similar to those enrolled in this study lower levels of β-carotenes (0.34μmol/L; p<0.001) and retinol (1.98μmol/L; p<0.01) as compared to non-smokers (0.53μmol/L and 2.0μmol/L) respectively. A modest correlation was also found between β-carotene levels and smoking (Spearman's r=0.170; p=0.006). However, cigarette smoking has been reported to affect plasma levels of other substances with antioxidant capacity such as lycopene, lutein, α-tocopherol, and β-tocopherol, but to have less influence on β-carotene levels, for which smoking is considered to be a determinant independent of dietary intake.32

Together with smoking, advanced age may be an additional factor for decreasing plasma levels of antioxidant vitamins.33 Moreiras and Carbajal34 found negative correlations of plasma levels of α-tocopherol and β-carotenes with the number of cigarettes smoked (r=0.188) and smoker age (r=0.304), p<0.05. In our study, this relationship was only found in the general population (subjects aged≥33 years [OR=1.62; 95% CI=1.31–2.01], p<0.05), with no sex differences. In agreement with these results, several studies have supported the influence of advanced age and altered body composition on changes in antioxidant substance levels.35,36 There are however no studies which assess this relationship with the RRS technique. Moreover, no sex differences or associations were found between β-carotene skin levels and the confounding factors assessed (BMI, waist circumference, and ethnicity, a finding which agrees with other reports.32–35,37–39

The results of this study suggest that non-invasive measurement of β-carotene levels in the skin using RRS is reproducible and reliable in humans. It should also be noted that β-carotene levels were normally distributed in the study population, and that the values agreed with the mean levels reported by international studies proposing this type of population measurement.11–15

One significant advantage of using the RRS technique is the rapid measurement of β-carotene skin levels, because no sample preparation or special measurement conditions are required.11–15 RRS has rapidly evolved in recent years to become a simple, accessible test due to its low cost and high reliability. RRS is currently an important test procedure for identifying antioxidant status, and is being rapidly adopted by specialists in endocrinology and nutrition in clinical40 and epidemiological41 studies, although it is less commonly used in clinical practice. As regards feasibility of use, the subjects assessed showed no adverse responses to the scanner in any of the measurements, including data acquisition and processing time. Our findings also suggest that the palm of the hand is among the best sites for measuring β-carotene skin levels using RRS, as this was the site with higher concentrations and greater ICC (probably related to higher β-carotene levels), as previously reported by Mayne et al.6

Finally, while the RRS technique is not new, it provides solutions for the rapid analysis of β-carotene skin levels in population studies and is highly likely to be used in clinical practice. A limitation of our study was the number of participants with highly pigmented skin, which prevented an efficient assessment of the impact of skin melanin on β-carotene levels. Our study population was limited to subjects under 65 years of age because skin quality may change with age, although this should be of minor concern in areas such as the palm of the hand. Future studies should include an adequate representation of participants with a full range of skin pigmentations, direct measurements of melanin content, and older age groups. Few studies have measured skin carotenoid levels and their impact on human health.11–15 Future studies may consider the addition of this important biomarker in tissues such as skin as a marker of nutritional and antioxidant status. Measurements by RRS will have to be incorporated into epidemiological studies before clinical inferences can be made about the impact of this biomarker on health.

In conclusion, RRS is a reliable method for non-invasive measurement of β-carotene levels in skin, and may be used as an important biomarker of antioxidant status in nutritional and health studies in humans.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ramírez-Vélez R, et al. Valoración no invasiva de los niveles de β-carotenos en piel en adultos colombianos. Endocrinol Nutr. 2012;59:304–10.