The aim of this study was to detect people at risk of suffering diabetes or changes in carbohydrate metabolism and to refer them for possible diagnosis to health care centers. The number of diagnoses and costs for the pharmacy were recorded.

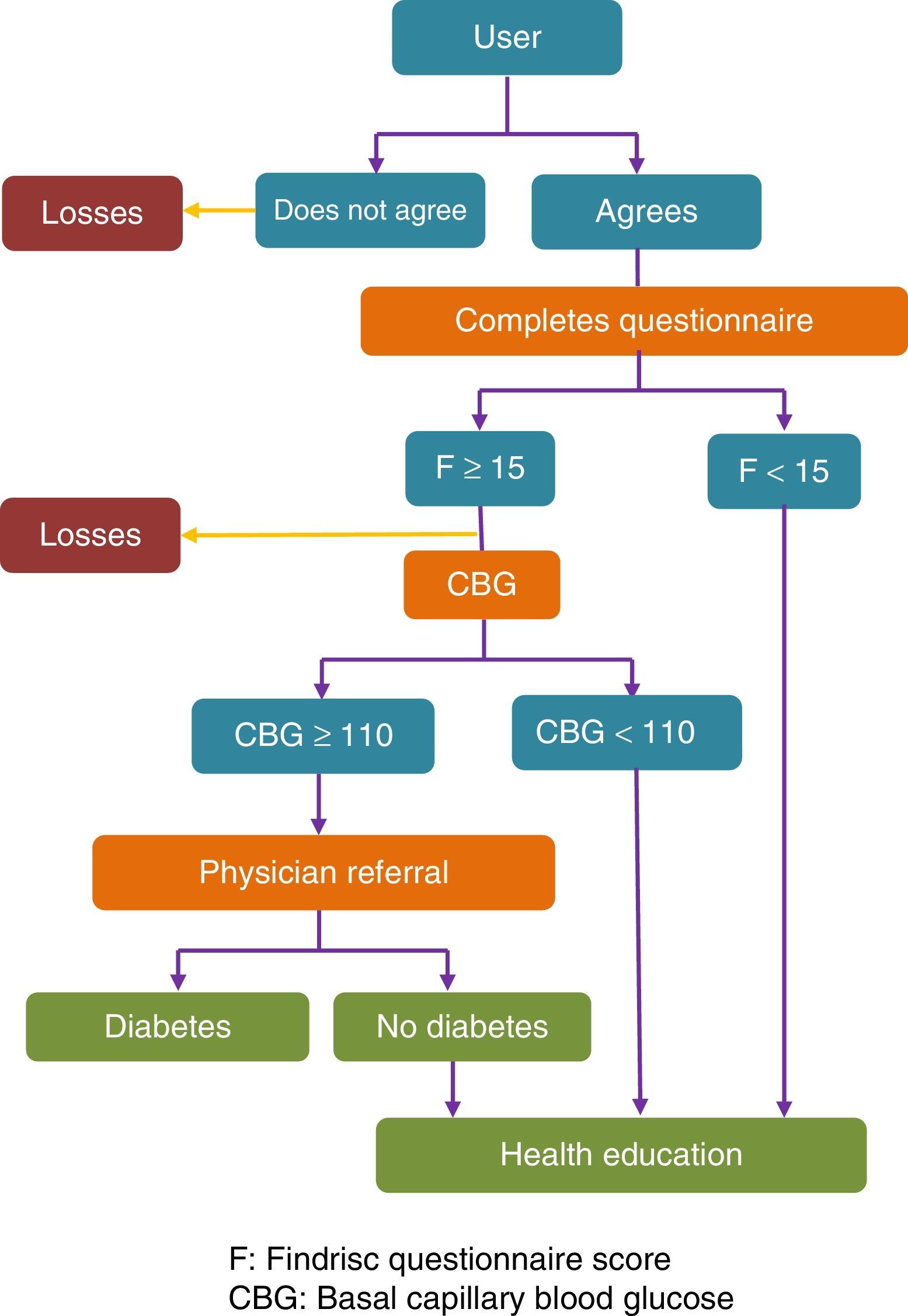

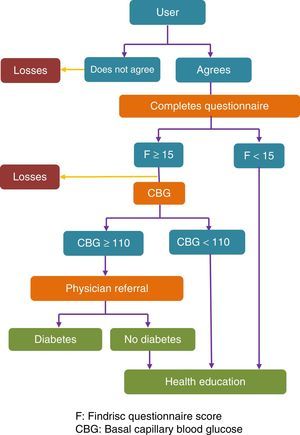

MethodsA cross-sectional, observational study was conducted in community pharmacies in Pontevedra in September–October of 2014. The Findrisc questionnaire was completed by pharmacy users over 18 years old. If Findrisc score was ≥15, capillary blood glucose was measured, and the participant was referred to a physician if the value was ≥110mg/dL. The main variables included score in the Findrisc questionnaire, number of diabetes diagnosed, and cost of the service.

Differences between the groups were calculated using a Chi-squared test, a Student's t test, and/or a Wilcoxon test.

ResultsThis study was conducted in 180 pharmacies on a sample of 4222 users, including 992 (23.5%) with a high or very high risk of diabetes (F≥15). In the 1060 basal capillary blood glucose tests performed, mean glucose level was 110.2 (SD=20.4)mg/dL (56–254). The Galician Health Service sent information about 83 of the 384 (9.1%) subjects referred to a physician: 28 (33.7%) of them were diagnosed with diabetes (3.1% of the sample), and 26 (31.3%) were diagnosed with prediabetes (2.8% of the sample).

Cost per diagnosed subject was €184.22 per subject with diabetes and €96.86 per subject with prediabetes.

ConclusionsThe proportion of subjects with new diagnosis of diabetes (3.1%) shows the high efficiency of a screening program for hidden diabetics implemented at community pharmacies as the one presented here.

Pilotar una actividad profesional consistente en la detección de personas en riesgo de padecer diabetes o alteraciones del metabolismo de los hidratos de carbono y derivación para posible diagnóstico en los centros de salud. Comprobación del número de diagnósticos y evaluación del coste para la farmacia.

MétodosEstudio observacional transversal en farmacias comunitarias de Pontevedra en septiembre-octubre de 2014. Cuestionario Findrisc a usuarios de la farmacia con más de 18 años. Con Findrisc≥15 determinación de la glucemia basal capilar y derivación al médico con ≥110mg/dL. Variables principales: puntos en cuestionario Findrisc, número de diagnósticos de diabetes, coste del servicio.

Las diferencias entre grupos se calcularon con el test de chi-cuadrado, t de Student o test de Wilcoxon.

ResultadosEl estudio se realizó en 180 farmacias. La muestra incluyó a 4.222 usuarios. De ellos, 992 (23,5%) tenían alto o muy alto riesgo de diabetes (F≥15). Se realizaron 1.060 test de glucemia basal capilar, con un resultado medio de 110,2 (DE=20,4)mg/dL (56-254). De los 384 (9,1%) sujetos derivados al médico, el Servicio Gallego de Salud envió información de 83: 28 (33,7%) diagnosticados de diabetes (3,1% de la muestra) y 26 (31,3%) de prediabetes (2,8%). El coste por sujeto diagnosticado fue de 184,22 € y por sujeto con diabetes o prediabetes fue de 96,86 €.

ConclusionesEl número de diagnósticos de nuevos pacientes diabéticos, 3,1% de la muestra total, muestra la alta eficiencia de un programa de cribado para diabéticos ocultos realizado en farmacias comunitarias como el que aquí se presenta.

The 2009 National Health Survey1 estimated the prevalence of diabetes in Spain at 5.9% (5.8% in females and 6.0% in males). A recent study conducted in Spain2 found that almost 30% of the population had some change in carbohydrate metabolism, and that the overall age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 13.8%. Diabetes was undiagnosed in almost half the cases (6.0%).

In a study reported in 2011 based on data from “electronic health information systems” about which no details were given, Domínguez González et al.3 estimated a 4.7% prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in Galicia, with a wide variability between the different health areas (4.2–6.4%).

People with undiagnosed T2DM are at a high risk of developing cardiac disease, dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, and obesity as compared to the nondiabetic population. Therefore, early detection and early treatment decrease disease progression and severity, as well as future complications.4,5

The risk of suffering diabetes is currently estimated as being similar to cardiovascular risk. The Findrisc (FINnish Diabetes RIskSCore) questionnaire, validated in 2012 for the Spanish population by Soriguer et al.,6 is considered one of the most efficient screening tools.

Screening for diabetes using the Findrisc questionnaire is recommended by international bodies such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)7 and the Canadian Task Force,8 and by national organizations such as the Spanish Society of Diabetes (SED).9 It has been used in public diabetes detection campaigns,10 health care centers,11 and community pharmacies (CFs).12–14 The experience of the screening of undiagnosed subjects by pharmacists at CFs, based on the estimation of the risk of developing DM using the Findrisc questionnaire,12–14 has been a very positive one.

Therefore, because of the accessibility and proximity to the population of community pharmacies and pharmacists, the Pontevedra medical association, in collaboration with the Galician Health Service (SERGAS), decided to undertake at the community pharmacies of Pontevedra a professional program aimed at detecting people at risk of diabetes or changes in carbohydrate metabolism and referring them for possible diagnosis to health care centers. The specific objectives included:

- •

To detect people with a high or very high risk of suffering diabetes using the Findrisc test.

- •

To confirm the situation as regards the value of basal capillary blood glucose.

- •

To characterize the types of intervention of the pharmacists involved as a function of the results obtained.

- •

To assess the number of new diagnoses of diabetes made as a consequence of referral to a physician.

- •

To assess the economic impact of the activity.

This was an observational, cross-sectional study with an educational intervention in community pharmacies located in the Pontevedra and Vigo health care areas.

SubjectsParticipants were enrolled between 19 September and 18 November 2014.

Inclusion criteria: pharmacy users with a SERGAS health card, who were over 18 years of age, not diagnosed with diabetes and who agreed to the test.

Exclusion criteria: pharmacy users who were under 18 years or who were not receiving health care from the SERGAS; subjects unwilling or unable to complete the questionnaire; users previously diagnosed with DM or who were taking medication for diabetes.

Sample size calculationTo calculate the sample size required, the results of a prior study conducted in the same setting,12 which found that 9.2% of subjects were at a high or very high risk of suffering DM, were taken into account. On the assumption that similar risk prevalence figures would be found, with a 95% confidence interval (CI), taking into account a bivariate hypothesis, and based on a target population of 805,900, the sample required was 3200 subjects. To compensate for potential losses, estimated at 25%, the fixed target was 4500 subjects, distributed among the pharmacies of Pontevedra participating in the study.

RandomizationSubjects randomly selected among those entering the pharmacy during morning opening hours were recruited into the study. The service was offered to the first, third, fifth, seventh users, etc. until two users had been enrolled daily and the total number of participants assigned to the pharmacy was completed.

Variables and measurement systems- •

Sociodemographic variables: age (years), sex (male/female), smoker (yes/no).

- •

Main variable:

- ∘

Total score in the Findrisc test (points). Five risk subgroups were established:

- •

Low: <8 points.

- •

Slightly increased: 8–11 points.

- •

Moderate: 12–14 points.

- •

High: 15–20 points

- •

Very high: >20 points.

- •

- ∘

- •

Other variables were as follows: the number of diagnoses of diabetes after referral, basal capillary blood glucose (CBG) (mg/dL), the body mass index (kg/m2), waist circumference (cm), physical activity (yes/no), the daily consumption of fruit (yes/no), the use of drugs for blood pressure (yes/no), prior high glucose levels (yes/no), relatives with diabetes (no/1st degree/2nd degree).

- •

Sociodemographic data: an ad hoc questionnaire including the relevant questions of the Findrisc questionnaire.

- •

Weight and height: a calibrated electronic scale with a stadiometer or a calibrated electronic scale+validated manual stadiometer.

- •

Waist circumference: an unextendable measuring tape. Measured at the midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest.7,10

- •

The measurement of basal blood glucose: capillary puncture and measurement with a validated OneTouch Verio® glucometer. Glucose dehydrogenase procedure.

To assess the cost of the activity, the mathematical model developed by Sanz Granda15 was used to calculate the costs of drug dispensing because of the similarity of the elements involved. The three components taken into consideration were labor cost (the salary and the social security of the pharmacist), infrastructure cost (the running costs of the pharmacy), and the cost of materials (glucometer, dipstick, gloves, recording form, information leaflet, etc.). The formula 0.5×T+M, where T is the time devoted to interaction with the subject and M is the cost of the materials used, was applied.

ProcedureThe program was jointly presented by the pharmacists’ association of Pontevedra and the SERGAS to area managers, medical and nursing managers, heads of department of health care centers and to community pharmacists. The pharmacists participating received general training on the pharmaceutical care of people with diabetes and specific training on program activities.

Fig. 1 shows a flow chart of the procedure used.

The different interventions depending on the results of the questionnaire and CBG were agreed by the multidisciplinary team that designed the project. They were based on the recommendations of the SED for the diagnosis and management of prediabetes.9

Ethical issuesAccording to the report of the regional research ethics committee, the pilot program required no approval because the activities were part of the standard practice at pharmacies. Informed consent was requested from participants who were referred to a physician, as data collected from the questionnaire were transferred to him/her.

An anonymous analysis of pooled study data was performed, so that individual participants could not be identified.

Statistical processingQuantitative variables are given as mean, standard deviation, and 95% CI. Relative frequencies were calculated for the categorical variables of the questionnaire. Differences between groups were calculated using Chi-square, Student's t, or Wilcoxon tests. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsStudy characteristicsOf the 394 pharmacies employing 1051 pharmacists in the Pontevedra and Vigo areas, 186 were enrolled. Surveys were performed at 180 (45.7%) pharmacies by 404 pharmacists (38.4%). The mean number of surveys by pharmacy was 23.5 (SD=8.9).

Sample characteristicsThe service was offered to 5061 users, and was accepted by 4578 (90.5%). Of these, 75 (1.6%) did not adequately complete the survey or did not return for the blood glucose test, while 281 users (6.1%) were not included in the study. Of all the users lost, 211 (59.3%) were women and 145 (40.7%) were men. The mean agewas 55.3 (SD=14.8) years; the highest number of losses occurred in the group aged >64 years (30.9%).

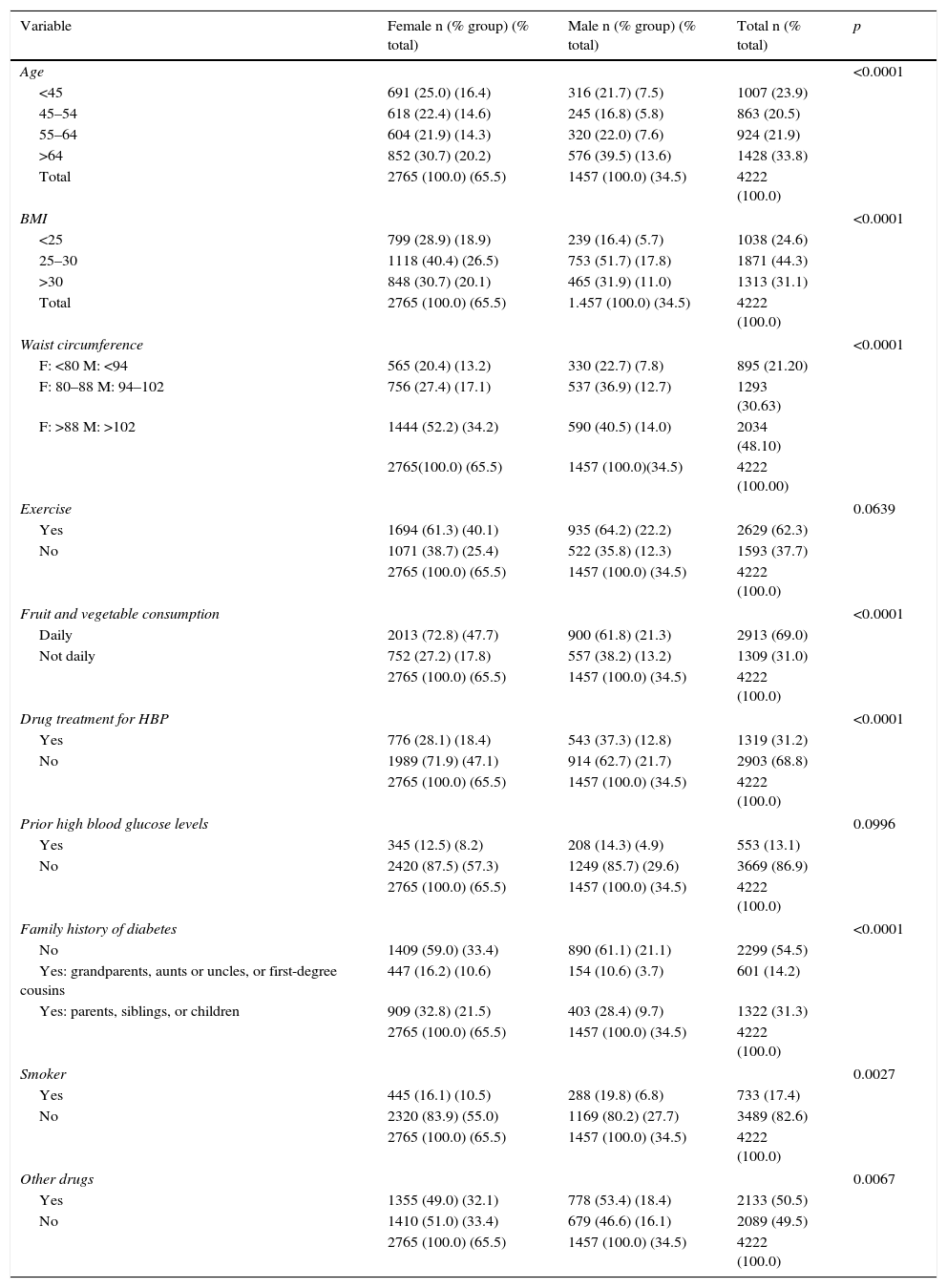

The sample therefore consisted of 4222 users, 84.4% of those offered the service. Table 1 shows sample characteristics and the results of the Findrisc questionnaire.

Sample characteristics and results of the Findrisc questionnaire.

| Variable | Female n (% group) (% total) | Male n (% group) (% total) | Total n (% total) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.0001 | |||

| <45 | 691 (25.0) (16.4) | 316 (21.7) (7.5) | 1007 (23.9) | |

| 45–54 | 618 (22.4) (14.6) | 245 (16.8) (5.8) | 863 (20.5) | |

| 55–64 | 604 (21.9) (14.3) | 320 (22.0) (7.6) | 924 (21.9) | |

| >64 | 852 (30.7) (20.2) | 576 (39.5) (13.6) | 1428 (33.8) | |

| Total | 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | |

| BMI | <0.0001 | |||

| <25 | 799 (28.9) (18.9) | 239 (16.4) (5.7) | 1038 (24.6) | |

| 25–30 | 1118 (40.4) (26.5) | 753 (51.7) (17.8) | 1871 (44.3) | |

| >30 | 848 (30.7) (20.1) | 465 (31.9) (11.0) | 1313 (31.1) | |

| Total | 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1.457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | |

| Waist circumference | <0.0001 | |||

| F: <80 M: <94 | 565 (20.4) (13.2) | 330 (22.7) (7.8) | 895 (21.20) | |

| F: 80–88 M: 94–102 | 756 (27.4) (17.1) | 537 (36.9) (12.7) | 1293 (30.63) | |

| F: >88 M: >102 | 1444 (52.2) (34.2) | 590 (40.5) (14.0) | 2034 (48.10) | |

| 2765(100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0)(34.5) | 4222 (100.00) | ||

| Exercise | 0.0639 | |||

| Yes | 1694 (61.3) (40.1) | 935 (64.2) (22.2) | 2629 (62.3) | |

| No | 1071 (38.7) (25.4) | 522 (35.8) (12.3) | 1593 (37.7) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

| Fruit and vegetable consumption | <0.0001 | |||

| Daily | 2013 (72.8) (47.7) | 900 (61.8) (21.3) | 2913 (69.0) | |

| Not daily | 752 (27.2) (17.8) | 557 (38.2) (13.2) | 1309 (31.0) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

| Drug treatment for HBP | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 776 (28.1) (18.4) | 543 (37.3) (12.8) | 1319 (31.2) | |

| No | 1989 (71.9) (47.1) | 914 (62.7) (21.7) | 2903 (68.8) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

| Prior high blood glucose levels | 0.0996 | |||

| Yes | 345 (12.5) (8.2) | 208 (14.3) (4.9) | 553 (13.1) | |

| No | 2420 (87.5) (57.3) | 1249 (85.7) (29.6) | 3669 (86.9) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

| Family history of diabetes | <0.0001 | |||

| No | 1409 (59.0) (33.4) | 890 (61.1) (21.1) | 2299 (54.5) | |

| Yes: grandparents, aunts or uncles, or first-degree cousins | 447 (16.2) (10.6) | 154 (10.6) (3.7) | 601 (14.2) | |

| Yes: parents, siblings, or children | 909 (32.8) (21.5) | 403 (28.4) (9.7) | 1322 (31.3) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

| Smoker | 0.0027 | |||

| Yes | 445 (16.1) (10.5) | 288 (19.8) (6.8) | 733 (17.4) | |

| No | 2320 (83.9) (55.0) | 1169 (80.2) (27.7) | 3489 (82.6) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

| Other drugs | 0.0067 | |||

| Yes | 1355 (49.0) (32.1) | 778 (53.4) (18.4) | 2133 (50.5) | |

| No | 1410 (51.0) (33.4) | 679 (46.6) (16.1) | 2089 (49.5) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

M, male; HBP, high blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; F, female.

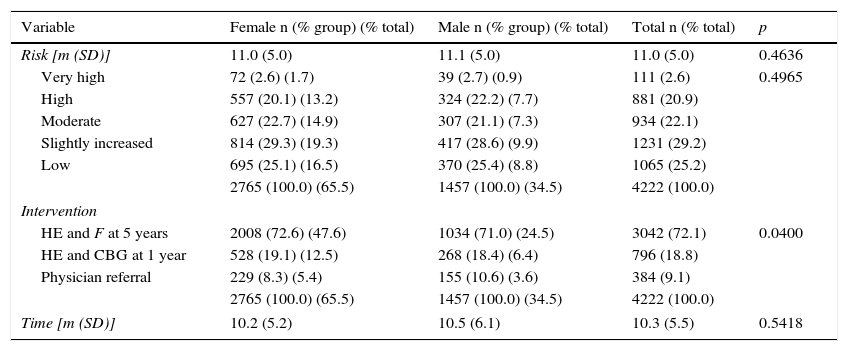

A total of 992 (23.5%) of the 4222 subjects surveyed were considered to be at a high or very high risk of diabetes (F≥15) (Table 2). Of these, 384 were referred to a physician; these represent 38.7% of those at a high or very high risk and 9.1% of all users surveyed.

Risk and intervention by sex.

| Variable | Female n (% group) (% total) | Male n (% group) (% total) | Total n (% total) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk [m (SD)] | 11.0 (5.0) | 11.1 (5.0) | 11.0 (5.0) | 0.4636 |

| Very high | 72 (2.6) (1.7) | 39 (2.7) (0.9) | 111 (2.6) | 0.4965 |

| High | 557 (20.1) (13.2) | 324 (22.2) (7.7) | 881 (20.9) | |

| Moderate | 627 (22.7) (14.9) | 307 (21.1) (7.3) | 934 (22.1) | |

| Slightly increased | 814 (29.3) (19.3) | 417 (28.6) (9.9) | 1231 (29.2) | |

| Low | 695 (25.1) (16.5) | 370 (25.4) (8.8) | 1065 (25.2) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

| Intervention | ||||

| HE and F at 5 years | 2008 (72.6) (47.6) | 1034 (71.0) (24.5) | 3042 (72.1) | 0.0400 |

| HE and CBG at 1 year | 528 (19.1) (12.5) | 268 (18.4) (6.4) | 796 (18.8) | |

| Physician referral | 229 (8.3) (5.4) | 155 (10.6) (3.6) | 384 (9.1) | |

| 2765 (100.0) (65.5) | 1457 (100.0) (34.5) | 4222 (100.0) | ||

| Time [m (SD)] | 10.2 (5.2) | 10.5 (6.1) | 10.3 (5.5) | 0.5418 |

SD, standard deviation; HE, health education; F, repeat Findrisc questionnaire; CBG, capillary blood glucose; m, mean.

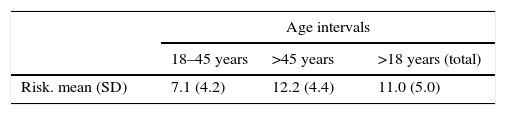

Of users younger than 45 years old, 1.1% were at a high risk and none at a very high risk, while 19.8% and 2.6% of users older than 45 years were at a high or very high risk respectively (Table 3).

Risk and intervention by age.

| Age intervals | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–45 years | >45 years | >18 years (total) | |

| Risk. mean (SD) | 7.1 (4.2) | 12.2 (4.4) | 11.0 (5.0) |

| No. (% group) (% total) | No. (% group) (% total) | No. (% group) (% total) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very high | 0 | 111 (3.5) (2.6) | 111 (2.6) |

| High | 47 (4.7) (1.1) | 834 (25.9) (19.8) | 881 (20.9) |

| Moderate | 117 (11.6) (2.8) | 817 (25.4) (19.4) | 934 (22.1) |

| Slightly increased | 266 (26.4) (6.3) | 965 (30.0) (22.8) | 1231 (29.2) |

| Low | 577 (57.3) (13.7) | 488 (15.2) (11.6) | 1065 (25.2) |

| Total | 1007 (100.0) (23.9) | 3215 (100.0) (76.2) | 4222 (100.0) |

| Intervention | |||

| HE and F at 5 years | 922 (91.6) (21.8) | 2120 (65.9) (50.2) | 3042 (72.1) |

| HE and CBG at 1 year | 76 (7.6) (1.8) | 720 (22.4) (17.1) | 796 (18.9) |

| Physician referral | 9 (0.9) (0.2) | 375 (11.7) (8.9) | 384 (9.1) |

| Total | 1007 (100.0) (23.9) | 3215 (100.0) (76.2) | 4222 (100.0) |

SD, standard deviation; HE, health education; F, repeat Findrisc questionnaire; CBG, capillary blood glucose; m, mean.

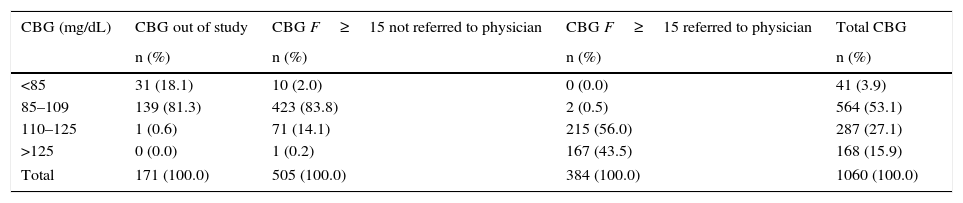

A total of 1060 basal capillary blood glucose measurements were performed (Table 4), and the mean value obtained was 110.2 (SD=20.4)mg/dL (56–254). Of these tests, 171 (16.1%) were not indicated in the procedure. Only 889 (85.5%) of the 992 tests that should have been performed to users with a high or very high risk were carried out, and the mean value obtained was 112.2 (SD=21.2mg/dL) (56–254).

Results of capillary basal blood glucose tests.

| CBG (mg/dL) | CBG out of study | CBG F≥15 not referred to physician | CBG F≥15 referred to physician | Total CBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| <85 | 31 (18.1) | 10 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 41 (3.9) |

| 85–109 | 139 (81.3) | 423 (83.8) | 2 (0.5) | 564 (53.1) |

| 110–125 | 1 (0.6) | 71 (14.1) | 215 (56.0) | 287 (27.1) |

| >125 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 167 (43.5) | 168 (15.9) |

| Total | 171 (100.0) | 505 (100.0) | 384 (100.0) | 1060 (100.0) |

CBG, basal capillary blood glucose.

Tables 2 and 3 show the interventions performed according to the described procedure. Only 0.2% of users under 45 years old, as compared to 8.9% of those older than 45 years were referred to a physician.

Referral outcomeAmong the 384 (9.1%) patients referred by the pharmacist to a physician, the SERGAS received information on the outcome of referral for 92 (24.0%) patients, of whom 9 (9.8%) did not visit the physician, or the physician did not record a visit related to DM. Of the 83 patients with a known outcome, 28 (33.7%) were diagnosed with diabetes and 26 (31.3%) with prediabetes, while impaired blood glucose was not confirmed in 29 (34.9%). Extrapolating the data to the overall sample, if information was available about all users referred to a physician, the diagnoses of DM would represent 3.1% and those of prediabetes, 2.8%.

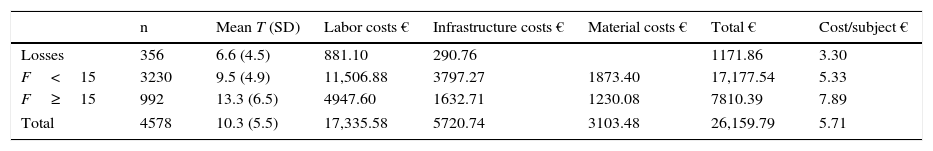

Cost of the serviceTable 5 shows the cost of the activity depending on the type of action with the subject and the time spent. The mean interview time was 10.3min (SD=5.5). The overall individual cost was €5.71; the cost by subject with Findrisc ≥15, €26.37; the cost of users referred to a physician (F≥15 and blood glucose >110mg/dL), €68.12; the cost by person diagnosed with DM, taking into account the extrapolation calculated, €184.22, and cost by person with impaired blood glucose (DM or prediabetes), €96.89.

Costs of pilot study.

| n | Mean T (SD) | Labor costs € | Infrastructure costs € | Material costs € | Total € | Cost/subject € | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Losses | 356 | 6.6 (4.5) | 881.10 | 290.76 | 1171.86 | 3.30 | |

| F<15 | 3230 | 9.5 (4.9) | 11,506.88 | 3797.27 | 1873.40 | 17,177.54 | 5.33 |

| F≥15 | 992 | 13.3 (6.5) | 4947.60 | 1632.71 | 1230.08 | 7810.39 | 7.89 |

| Total | 4578 | 10.3 (5.5) | 17,335.58 | 5720.74 | 3103.48 | 26,159.79 | 5.71 |

SD, standard deviation; F, Findrisc questionnaire score; T, time.

The program for the detection of diabetic subjects at pharmacies in the province of Pontevedra (DEDIPO) allowed us to detect in a large sample a substantial number of people at a high or very high risk of developing diabetes. We think that guiding these people to the health care team, who can provide them with a diagnosis, when applicable, or with general information, health information, monitoring, and control may contribute to delaying the occurrence or progress of the disease and the occurrence of complications. The involvement of pharmacists from almost half the pharmacies of the province and widespread user acceptance suggests that a program of this type may be of interest as a professional service that could be provided at pharmacies in collaboration with the health service.

The sample loss expected was close to 25%, but was actually less than 20%. The sex and age characteristics of the lost sample were similar to those of the final sample, and these losses were therefore not considered to have influenced the results. Our sample was larger than that of other studies in both community pharmacy13 and primary care6,16 or in a non-health care setting.10

More than 65% of the participants were women, more than 75% of all respondents were older than 45 years, and more than 75% had waist circumference values higher than normal and had overweight or obesity, this being more marked in men. These rates are higher than those estimated for the adult population in Spain,17 for which prevalence rates of overweight and obesity of 34.2% and 13.6% respectively have been reported.

More than 62% of subjects stated that they performed at least 30min of exercise daily, and 69% reported a daily consumption of vegetables or fruit. These rates are lower than those reported in a national study,13 but higher than those found in another study.10 It is quite possible, however, that these responses are overstated due to patient self-perception, so that the score obtained in the questionnaire should be lower. If so, the actual number of subjects at a high/very high risk would be higher than that actually detected.

The proportion of subjects at a high or very high risk of developing diabetes found in this study (23.5%) agrees with that reported in a recent national study also conducted at community pharmacies (24.3%).13 The rates reported range from 9.6% to 45% in studies conducted in Spain and other countries using the same cut-off point, F≥15.6,18,19 Acosta20 found in health care centers in Madrid that 29% of subjects aged 45–70 years were at high risk. This proportion agrees with the one found in this study (29.4%) for this age group.

Controversy exists regarding the best cut-off point both in Spain14,16,21 and other countries.22 In 2010, Costa16 compared three methods based on a Findrisc test score >14 and confirmation with an oral glucose tolerance test, HbA1c, and basal blood glucose in a sample of subjects aged 45–75 years, and found prevalence rates of T2DM of 9.2%, 3.6%, and 3.1% using the different methods. The use of lower cut-off scores increases the number of cases of potential undiagnosed diabetics detected, but decreases efficiency.22 The selection of 110mg/mL of CBG as the reference value for physician referral is based on the SED guidelines for screening in two stages.9

Our study enrolled subjects aged 18 years or older to increase early detection. It found that risk increased with age and that, from the viewpoint of efficiency, the cut-off point should be 45 years, because no subjects under 45 years were at a very high risk, and only 47 (4.7%) out of 1007 subjects were at a high risk. Only 9 (0.9%) of users in this age group were referred to a physician, as compared to 375 (11.7%) of those over 45 years of age.

The proportion of CBG levels higher than 125mg/dL found in subjects referred to a physician (43.5%) was greater, but close to that of the diagnoses of DM reported by the SERGAS for those attending a physician (33.7%). This is a good indicator of the value of CBG as a predictor of DM diagnosis after screening using the Findrisc questionnaire.

In a relatively high number (287, 32.3%) of tests performed in subjects with F≥15, blood glucose levels ranging from 110 to 125mg/dL were found. These are higher levels than those found in the Di@betes study (14.8%),2 suggesting a state of prediabetes, which is associated with a greater risk of developing DM and suffering cardiovascular complications in the future,9 but the knowledge of which gives patients the possibility of making lifestyle changes to prevent or delay the progression to diabetes.7,23,24

Interventions with patients not referred to physicians (F<15 and F≥15 with CBG<110mg/dL), based on the NICE7 and Canadian Task Force criteria,8 were stratified based on risk and intended to ensure that participants in the program became aware of their glycemic status in order to start preventive actions and to monitor progression. A natural continuation of screening programs such as the one discussed here would be to reach a consensus with the multidisciplinary team on the action guidelines for these people attending community pharmacies in the setting of a program to prevent the progression to diabetes.

Reviews of recent interventional studies by community pharmacists25,26 support the effectiveness of their collaboration and show improvements in pharmacotherapeutic results, lifestyle, etc. by reducing cardiovascular risk factors and improving the quality of life of patients, along with a better use of health care resources.

In screening studies for occult diabetes conducted at community pharmacies in Spain, information about diagnosis was not always provided by physicians.12–14 This time, as this was a program in collaboration with the SERGAS, officially presented to the medical staff of the two health care areas where it was conducted, it was expected that more information would be obtained on referral outcomes. Although information was not obtained on all the subjects referred, it was verified that one third of those who attended a physician's office (28; 33.7%) were diagnosed with diabetes. Thus, the prevalence of diabetes in the sample may be estimated at 3.1%.

In the Diabnow study,27 conducted in 2012, 33.3% of subjects were referred, and 25 of them (18%), or 4.1% of all subjects, were diagnosed with diabetes. This is a somewhat greater proportion as compared to our study.

In a study conducted in community pharmacies in Switzerland using methods similar to our study,28 the prevalence of diabetes was estimated at 6.1%, with 1.9% being newly diagnosed cases. In the United States, 4.1% of new diabetic patients were detected in a sample of 20,633 adults over 20 years of age.29

The costs for the community pharmacy of screening for occult diabetes, €5.71 per participant, €188.22 per subject diagnosed with diabetes, and €96.89 per subject with impaired blood glucose, are reasonable considering the savings to the health care system. Early diagnosis enables drug and non-drug treatment to be started in order to slow disease progression and the occurrence of complications. The difference in annual costs for the health care system between a patient with microvascular and macrovascular complications and a patient with no complications is €1249.44.30 Thus, early detection at the above cost (€96.86 only once) of a new patient with impaired blood glucose who receives adequate care from the health care team allows for savings of €1249.44 per year of delay in the occurrence of microvascular and macrovascular complications.

The diagnoses of new diabetic patients made at a low cost with the DEDIPO program, estimated at 33.7% of referrals, or 3.1% of the total sample, shows the high efficiency of the community pharmacy and pharmacist in a program for screening occult diabetes such as the one reported here. Putting this program into general use as a remunerated professional service of pharmacists would result in substantial savings for the public health system by facilitating the entry of newly diagnosed diabetics into multidisciplinary comprehensive care programs, with a resultant delay in the occurrence of macrovascular and microvascular complications.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe authors state that no experiments with humans or animals were conducted in this research. They also state that all the procedures used met the regulations of the relevant ethics research committee and the World Medical Assembly and the Declaration of Helsinki.

FundingAll the materials used in the study were funded by the pharmaceutical companies Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, and Lifescan, which did not participate in any way in the design of the study or in how it was conducted, data analysis, or the interpretation or preparation of the manuscript.

Authorship/collaboratorsJAFP contributed to the study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, the writing of the draft article, and the final approval of the submitted version.

NFAR contributed to the study conception and design, data interpretation, the writing of the draft article and the critical review of the contents, and the final approval of the submitted version.

JAFP contributed to data analysis and interpretation, the writing of the draft article, and the final approval of the submitted version.

RLC contributed to the study conception and design, data interpretation, the critical review of the contents, and the final approval of the submitted version.

JGS contributed to the study conception and design, data interpretation, the critical review of the contents, and the final approval of the submitted version.

BLV contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation, the writing of the draft article, and the final approval of the submitted version.

RMG contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation, the writing of the draft article, and the final approval of the submitted version.

PGR contributed to the study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, the critical review of the contents, and the final approval of the submitted version.

No subject data have been kept, except in the event of physician referral, when adequate information was provided and informed consent was requested. In this case, data required for the study were handled in aggregate form, with no personal identification.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to the contents of the manuscript.

We thank the community pharmacists of the 180 pharmacies participating in this study. We thank the pharmacists of the Information Center on Medicines (CIM) from the Pontevedra Pharmacists’ Association. We would also like to thank Alba Soutelo, chair of the Pontevedra Pharmacists’ Association, and Félix Rubial, Julio González and Blanca Cimadevila, from the Galician Health Service, who made this study possible.

We also thank the pharmaceutical companies Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, and Lifescan for their financial support to this pilot study.

Please cite this article as: Fornos-Pérez JA, Andrés-Rodríguez NF, Andrés-Iglesias JC, Luna-Cano R, García-Soidán J, Lorenzo-Veiga B, et al. Detección de personas en riesgo de padecer diabetes en farmacias comunitarias de Pontevedra (DEDIPO). Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:387–396.