Prevalence of obesity is increasing in most developed countries due to lifestyle changes, and in moderate to severe obesity with comorbidities bariatric surgery is greatly relevant in treatment, although it involves the need for subsequent follow-up for preventing the occurrence of nutritional deficiencies or other complications.1

Postprandial hypoglycemia with hyperinsulinism after laparoscopic gastric bypass (LGB) is an uncommon complication with an estimated prevalence of 0.2%.2 The two cases reported here occurred among approximately 928 bariatric surgeries, 492 of them GBs, performed at our center from 2000. This represents an approximate prevalence of 0.4%, slightly higher than previously reported.2 The condition typically occurs 1–3h after meals and starts 1–3 years after surgery, although cases have been reported to occur as early as three months after the procedure.3 Symptoms of severe neuroglycopenia may lead to hypoglycemic coma or seizures, which highlights the potential severity of this condition.

A 36-year-old woman with history of gastric bypass performed on 2005 due to severe obesity (preoperative weight of 114kg, BMI 51kg/m2), attended our outpatient clinics two years after surgery reporting hypoglycemic episodes 2h after food intake. Episodes were occasionally self-limited, or resolved after sugar intake at other times. The patient then weighed 79.2kg, which was the minimum weight achieved after surgery. Hypoglycemic episodes increased in severity and frequency during the next two years, occasionally requiring family care at home due to impaired consciousness, but did not attend the emergency room. A 72-hour test was done twice for diagnosis with no pathological results. A ACTH stimulation test ruled out adrenal insufficiency. An abdominal CT scan showed no pathological findings. A glucose tolerance test was also performed, showing hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinism. Finally, pancreatic catheterization with selective calcium stimulation test provided results consistent with pancreatic beta cell hyperplasia (Table 1). As regards management, treatment was started with acarbose, with negative results. Long-acting octreotide (10mg monthly) was subsequently administered, achieving a partial and short-lived response. Finally, diazoxide was started at increasing doses until the maximum dose for hypoglycemia control was achieved, and patient was referred to general surgery for corporocaudal pancreatectomy. Preoperative ultrasound examination showed no tumor. The pathological laboratory reported endocrine cell diffuse hyperplasia in islets of Langerhans and pancreatic ducts consistent with nesidioblastosis. Patient restarted after surgery a fractionated diet, and has remained symptom-free for 18 months after surgery, with normal blood glucose levels and no further hypoglycemic episodes.

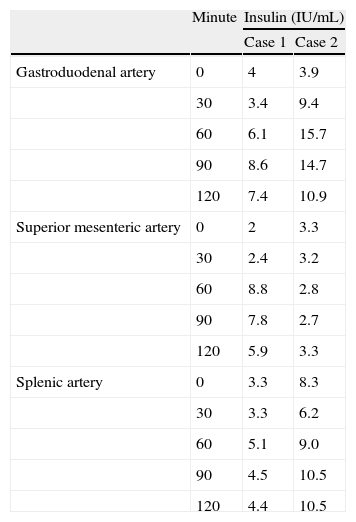

Results of the selective calcium stimulation test.

| Minute | Insulin (IU/mL) | ||

| Case 1 | Case 2 | ||

| Gastroduodenal artery | 0 | 4 | 3.9 |

| 30 | 3.4 | 9.4 | |

| 60 | 6.1 | 15.7 | |

| 90 | 8.6 | 14.7 | |

| 120 | 7.4 | 10.9 | |

| Superior mesenteric artery | 0 | 2 | 3.3 |

| 30 | 2.4 | 3.2 | |

| 60 | 8.8 | 2.8 | |

| 90 | 7.8 | 2.7 | |

| 120 | 5.9 | 3.3 | |

| Splenic artery | 0 | 3.3 | 8.3 |

| 30 | 3.3 | 6.2 | |

| 60 | 5.1 | 9.0 | |

| 90 | 4.5 | 10.5 | |

| 120 | 4.4 | 10.5 | |

Pathological results (insulin increase to at least double the baseline level) are seen at 90min in gastroduodenal artery samples, from 60min in the superior mesenteric artery in patient 1, and from 30min in the gastroduodenal artery in patient 2.

The second case was a 36-year-old woman who underwent GB in 2006 for morbid obesity (preoperative weight 140kg, BMI 46.24). A year and a half after surgery and with a weight of 79kg (minimum weight after surgery, 77kg), patient experienced daily postprandial hypoglycemia, sometimes associated to syncopal symptoms which required family intervention for resolution, but not hospital treatment. An overload test with a mixed meal (Ensure plus drink®, one 200mL bottle) showed hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (blood glucose 28mg/dL), insulin (10.6IU/mL). A fasting test showed no pathological results (minimal blood glucose 42mg/dL with insulin <0.2IU/mL), and ACTH stimulation ruled out adrenal insufficiency. An abdominal CT scan showed no nodular lesions in the pancreas. Finally, pancreatic catheterization with selective calcium stimulation (Table 1) suggested hyperinsulinism. Fractionated diet was started, followed by treatment with acarbose. Both measures were ineffective. Octreotide treatment was subsequently administered with no improvement. Patient was referred to general surgery, and treatment with diazoxide was simultaneously started. Patient underwent corporocaudal pancreatectomy. Pathological examination found diffuse nesidioblastosis. Five months after surgery the patient continued on fractionated diet, with no specific treatment for hypoglycemia, and has remained symptom-free since then with normal blood glucose values.

The above reported cases suggested nesidioblastosis, but it is not simple to reach this conclusion, because the pathophysiological mechanisms of hypoglycemia after gastric bypass are not clear. The Meier group analyzed pancreatic tissue form patients with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after gastric bypass3 and found no significant changes. They postulated that they had a relative hyperinsulinemia4 where weight loss would increase insulin sensitivity, causing hypoglycemic episodes despite production of the same amount of insulin as before surgery. Rabbie et al. found high GLP-1 levels one year after bypass and related the increased insulin secretion to incretin action.2

Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia represents a great challenge for clinicians because of our limited understanding of the relationship between the above cited mechanisms. To diagnose this condition, reliable evidence of the presence of hypoglycemia should be obtained first, for which a mixed meal test, or even continuous glucose monitoring, which is the best option, may be used.5 Once this has been shown, the etiology should be sought, as discussed in other similar reviews.6 A detailed clinical history should first be taken to rule out causes other than bariatric surgery, as may be surreptitious use of insulin. Once this is ruled out, the endogenous mechanism responsible for the relative increase in insulin levels should be sought. The above tests will show the time of occurrence of hypoglycemic episodes, under fasting conditions or after meals. The first case would be consistent with insulinoma, which in principle would have no relationship with bariatric surgery, although weight loss could possibly decrease a prior insulin resistance, unmasking at that time a previously present insulinoma. In any case, functional imaging tests will subsequently be required to arrive to that diagnosis. Standard X-ray examinations may be combined with use of 18F-DOPA- or 11C-HTP-PET, both of them valid for this purpose, with no clear advantage of any of them over the other.7 The selective calcium stimulation test may also be used. An increase in insulin to at least double the baseline level after calcium injection into the splenic, superior mesenteric, and gastroduodenal arteries indicates beta cell hyperfunction.

There is no treatment of choice or standardized management helpful for all patients. The possibility that different pathophysiological mechanisms are involved in different patients could explain this situation. A strict diet should be the first step, but the available medical alternatives should be known in case it does not work. Medical treatment, for which different options are available, should subsequently be tried. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors have been used because of prior experience in patients with dumping syndrome.1 Other treatments traditionally used for hypoglycemic episodes include calcium channel blockers or diazoxide,8 which is more commonly used for hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in childhood. Because of the lack of efficacy of the above measures, new therapeutic options have appeared. Somatostatin analogues have been used and have shown long-term efficacy in some cases because of their inhibitory effect on insulin and GLP-1 secretion. Interestingly, GLP-1 analogues have successfully been used for that purpose. Their postulated mechanism of action is a stabilizing effect of blood glucose levels,9 although slowing of gastric emptying could be another plausible mechanism to explain their efficacy. However, medical treatment fails in a great number of cases, which leaves surgery as the only possible option. The procedure of choice in these patients is subtotal pancreatectomy, which has a 2–9% mortality rate and is not infallible.1 Another retrospective study10 showed improvement in all patients undergoing this treatment, but with different degrees of success. Total symptom resolution was achieved in approximately 25% of patients, while 25% had persistent mild symptoms, 25% required medical treatment after surgery, and the remaining 25% had persistent symptoms which could not be controlled with any type of medical treatment.

The reported cases show an excellent response to surgery after failure of multiple medical treatments. A precise diagnostic approach, including selective calcium stimulation, is needed to be able to select the best therapeutic option, either medical or surgical.

Ethical responsibilitiesWritten informed consent has been obtained for publication of the clinical cases reported here.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García Bray BF, Peromingo R, Galindo J, Arrieta F, Sánchez J, Vázquez C, et al. Tratamiento de las hipoglucemias graves tras bypass gástrico con pancreatectomía subtotal: a propósito de 2 casos. Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61:391–393.