Thyroid metastases of extrathyroid neoplasms account for less than 3% of all malignant thyroid tumours.1 Given their rarity, we report three cases that occurred in different clinical scenarios, before reviewing this condition and expounding upon its diagnosis in depth.

Case 1A 59-year-old man who smoked 45 pack-years, came in with an anterior neck mass that had gradually enlarged over the past three months. Thyroid ultrasound was performed, showing an enlarged gland with a "tiger-striped" appearance, no nodularity and multiple pathological bilateral swollen lymph nodes (Fig. 1). Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was performed on the gland and cytology and immunohistochemistry diagnosis confirmed PDL1-positive squamous cell lung metastasis. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck and chest was ordered, which revealed not only pathological thyroid and cervical lymph node findings but also a spiculated lung mass measuring 5cm in the right upper lobe. At the same time, the patient was diagnosed with squamous-cell carcinoma of the oral cavity with cervical, submandibular and supraclavicular involvement.

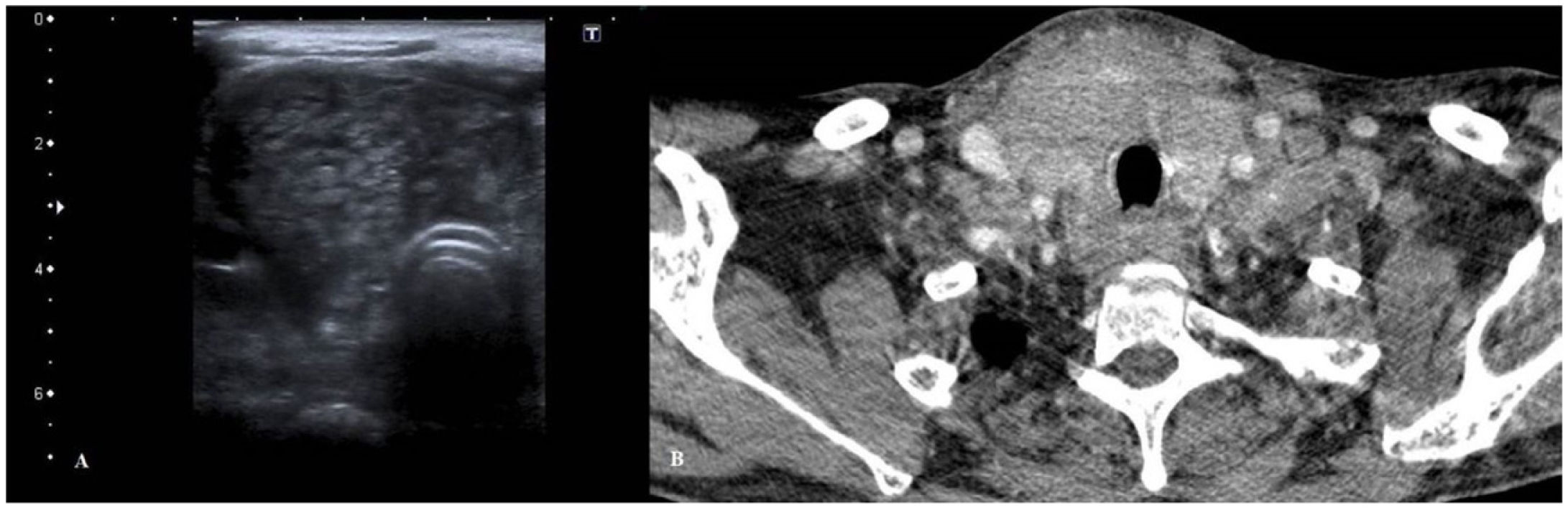

(A) Thyroid ultrasound. Enlarged right thyroid lobe with no clear nodularity. Heterogeneous echogenicity with a "tiger-striped" appearance. Lobe measuring 39mm in length. (B) CT scan of the neck. Generalised enlargement of the thyroid gland with a heterogeneous appearance. Bilateral pathological cervical lymphadenopathy. Decreased tracheal calibre.

Treatment was started with carboplatin and paclitaxel with cytoreductive intent, but after the first session the patient showed rapid clinical decline with dysphagia and dyspnoea, and therefore palliative sedation was pursued.

Case 2A 50-year-old woman with a history of metabolic syndrome had undergone a right nephrectomy 10 years earlier due to low-risk clear cell renal cell carcinoma. She was in follow-up by urology and her disease was in remission. A follow-up CT scan detected a bilateral multinodular goitre. Thyroid ultrasound showed a solid, isoechogenic (ACR-TIRADS 3)2 nodule on the left thyroid lobe (LTL) measuring 34mm. FNAB was performed on this nodule and it was diagnosed as benign. The right thyroid lobe (RTL) had a solid, hypoechogenic nodule with limited vascularisation (ACR-TIRADS 4) measuring 8mm. FNAB was not performed on this nodule due to lack of criteria. On a follow-up ultrasound after 18 months, the nodule on the RTL had doubled in size and increased in vascularisation. FNAB was performed on three occasions, all of which were unsatisfactory. As such, total thyroidectomy was performed to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. Sample analysis showed two foci of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (the larger one, on the right, measuring 17mm), with positivity for vimentin and RCC and focal positivity for CD10 and CK7. A staging CT scan further revealed two lung metastases measuring less than a centimetre. Therefore, treatment was started with sunitinib, then suspended due to lack of tolerance. The patient's disease is currently stable and being treated with nivolumab.

Case 3A 64-year-old man with a history of smoking (50 pack-years) and metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with lymphangitic carcinomatosis (T3N3M1a) was on treatment with pemetrexed with a partial response. He was referred due to rapid and progressive thyroid gland enlargement over the course of the past two months, causing significant dysphagia to both solids and liquids. Thyroid ultrasound revealed enlargement of both thyroid lobes due to two large, solid, isoechoic nodules with punctiform calcifications (ACR-TIRADS 4), one on the RTL measuring 37mm and other on the LTL measuring 35mm. In addition, bilateral pathological lymphadenopathy measuring up to 20mm was found in the cervical lymph node chains. FNAB was performed on the nodule on the RTL and on two swollen cervical lymph nodes, with a diagnosis of infiltration due to adenocarcinoma with an immunophenotype positive for TTF1 and negative for thyroglobulin, consistent with lung adenocarcinoma. The patient was admitted with complete dysphagia. As it was impossible to place a nasogastric tube, comfort measures were prioritised.

DiscussionThyroid gland metastases have a low prevalence in clinical practice, accounting for less than 0.1% of nodules that undergo FNAB.1 However, on autopsy, an incidence in oncology patients of 1.3%–25% of cases has been reported.3

The mechanism of metastatic involvement of the thyroid gland is usually through the haematogenous/lymphatic route and more rarely due to contiguity from adjacent structures.4 Lung and breast cancer metastases are the most common metastases in autopsy series. By contrast, in clinical series, clear cell renal cell carcinoma is more typical3; it may metastasise to the thyroid gland long after primary resection,4 as in Case 2.

Metastases may present as diffuse infiltration of the gland3 or with the appearance of thyroid nodules on complementary tests in patients with a history of cancer. A presentation in the form of a neck mass due to bilateral thyroid enlargement in patients with no history of cancer is considered rare,5 hence the peculiarity of Case 1. The essential clinical characteristic common to all the cases reported was rapid growth. This sign mandates suspicion of thyroid metastases, especially in patients with a history of cancer or risk factors.4

On ultrasound, generalised enlargement of the gland featuring a heterogeneous appearance with atypical hypoechoic lines is usually observed, and some series have reported pathological lymphadenopathy in up to 92% of cases.6 No imaging tests distinguish between primary thyroid cancer and metastases.7

Therefore, for an accurate diagnosis, cytology or histology testing of a specimen obtained via FNAB (which enables diagnosis of up to 90% of thyroid metastases),8 core needle biopsy (CNB) or surgical resection is indispensable. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma and lymphoproliferative disorders may show morphological characteristics that overlap with primary thyroid neoplasms.3 Given that they tend to be less differentiated cancers, immunohistochemistry techniques aid in differential diagnosis since each primary cancer presents different types of markers. Differentiated primary thyroid cancers express thyroglobulin, whereas metastases do not; lung adenocarcinoma shows positivity for napsin A; clear cell renal cell carcinoma shows positivity for RCC, vimentin and CD10; and lymphoproliferative syndromes express lymphocytic markers (CD45, CD3, CD20, CD30, etc).

In general, the prognosis is unfavourable. However, it is influenced by the extent of metastatic involvement and the nature of the primary cancer (two-year survival rates are 20% for lung carcinoma versus 70% if of renal origin). Total thyroidectomy, when possible, has a positive impact on survival.9 Given its prognostic power, differential diagnosis between primary and metastatic lesions is key to proper decision-making.

FundingNo funding was received.

Conflicts of interestNone.