Despite the clinical, epidemiological, and economic significance of metabolic syndrome, the profile of clinical trials on this disease is unknown.

ObjectiveTo characterize the clinical trials related to treatment of metabolic syndrome during the 1980–2015 period.

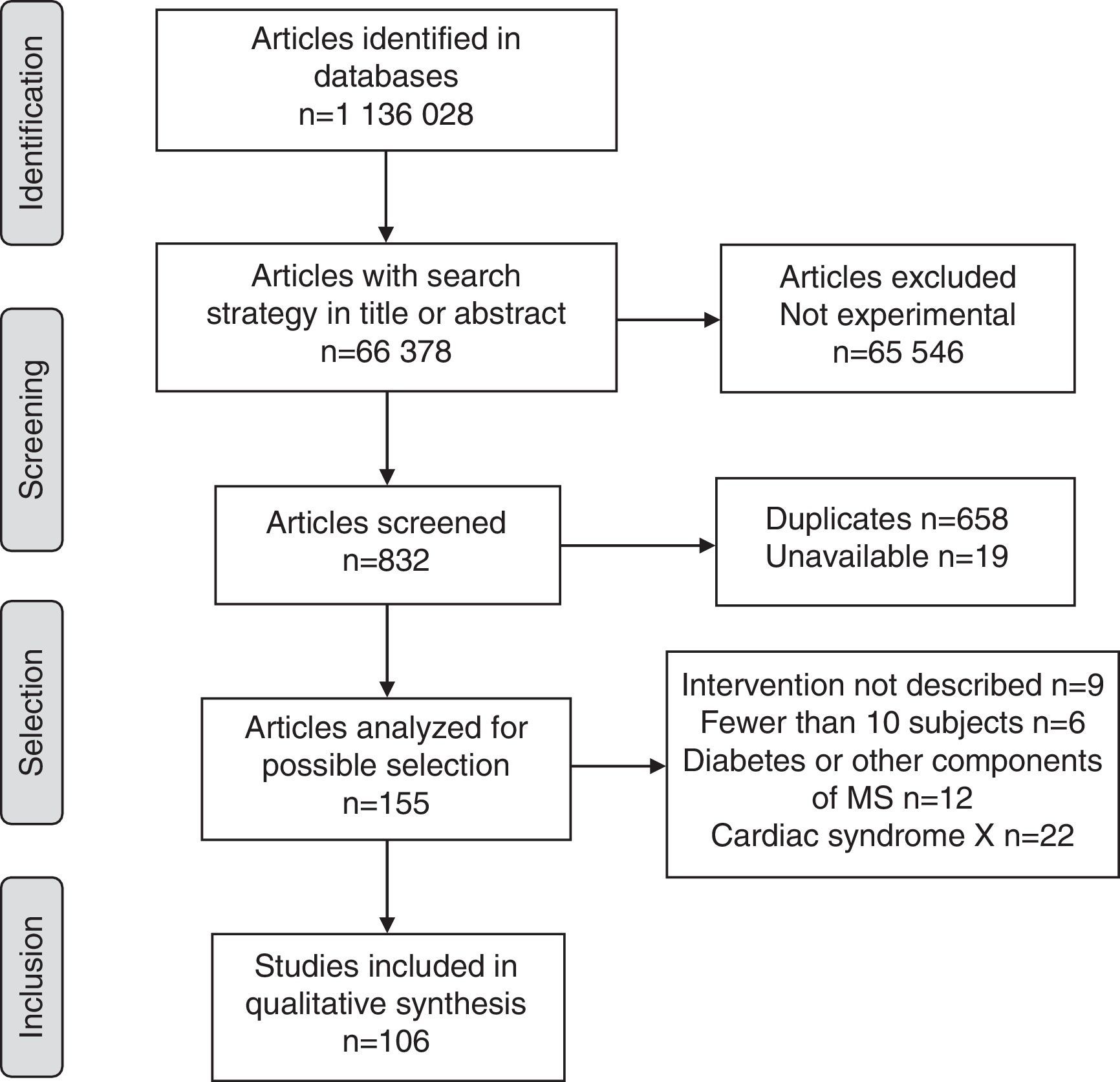

MethodsSystematic review of the literature using an ex ante search protocol which followed the phases of the guide Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in four multidisciplinary databases with seven search strategies. Reproducibility and methodological quality of the studies were assessed.

ResultsOne hundred and six trials were included, most from the United States, Italy, and Spain, of which 63.2% evaluated interventions effective for several components of the syndrome such as diet (40.6%) or physical activity (22.6%). Other studies assessed drugs for a single factor such as hypertension (7.5%), hypertriglyceridemia (11.3%), or hyperglycemia (9.4%). Placebo was used as control in 54.7% of trials, and outcome measures included triglycerides (52.8%), HDL (48.1%), glucose (29.2%), BMI (33.0%), blood pressure (27.4%), waist circumference (26.4%), glycated hemoglobin (11.3%), and hip circumference (7.5%).

ConclusionIt was shown that studies ob efficacy of treatment for metabolic syndrome are scarce and have mainly been conducted in the last five years and in high-income countries. Trials on interventions that affect three or more factors and assess several outcome measures are few, and lifestyle interventions (diet and physical activity) are highlighted as most important to impact on this multifactorial syndrome.

A pesar de la importancia clínica, epidemiológica y económica del síndrome metabólico, a la fecha se desconoce el perfil de los ensayos clínicos disponibles para esta enfermedad.

ObjetivoCaracterizar los ensayos clínicos relacionados con el tratamiento del síndrome metabólico durante el periodo 1980-2015.

MétodosRevisión sistemática de la literatura con un protocolo de búsqueda ex ante que cumplió las fases de la guía Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses en cuatro bases de datos multidisciplinarias con siete estrategias de búsqueda. Se evaluó reproducibilidad y calidad metodológica de los estudios.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 106 ensayos, la mayoría de Estados Unidos, Italia y España. El 63,2% evaluó intervenciones con eficacia para varios componentes del síndrome como dieta (40,6%) o actividad física (22,6%), las demás evaluaron medicamentos para uno de los factores como hipertensión (7,5%), hipertrigliceridemia (11,3%) o hiperglucemia (9,4%). En los controles el 54,7% usó placebo, y entre las variables de resultado el 52,8% incluyó triglicéridos, 48,1% cHDL, 29,2% glucemia, 33,0% IMC, 27,4% presión arterial, 26,4% perímetro de cintura, 11,3% hemoglobina glucosilada y 7,5% perímetro de cadera.

ConclusiónSe evidenció que los estudios sobre eficacia terapéutica para el síndrome metabólico son escasos y se concentran en el último quinquenio y en países de altos ingresos. Los ensayos sobre intervenciones que impactan tres o más factores y evalúan varias variables de resultado son reducidos, destacándose las intervenciones del estilo de vida (dieta y actividad física) como las de mayor importancia para impactar la multifactorialidad del síndrome.

Metabolic syndrome is defined as the presence of central obesity plus two of the following factors: triglyceride levels >150mg/dL (1.7mmol/L) or treatment to decrease them; HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels <40mg/dL (1.03mmol/L) or lipid-lowering treatment; systolic blood pressure >130mmHg, diastolic blood pressure >85mmHg or antihypertensive treatment; and fasting plasma glucose >100mg/dL (5.6mmol/dL) or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus.1,2

Metabolic syndrome (MS) is associated with diseases which have a high mortality rate worldwide. It encompasses a group of metabolic risk factors that increase the likelihood of conditions such as heart disease, hemorrhagic stroke, and diabetes mellitus.3 From the economic point of view, the direct and indirect costs associated with the control of insulin resistance have been estimated at US$ 1.015 billion, and this figure almost doubles when complications are taken into account.4 The direct and indirect costs of cardiovascular disease worldwide are expected to increase from US$ 863 billion in 2010 to US$ 1.04 trillion in 2030.5 The estimated direct and indirect costs of obesity represent 7%–20% of the total public health budget.6

Epidemiologically, the estimated prevalence of MS in developed countries such as the United States is 25% in males and 21% in females; among Mexican-Americans, prevalence is 29% in males and 33% in females. In Europe, the estimated values are 23% in males and 12% in females. The overall prevalence in the working population in Spain is 10.2% (11.9% in males and 2.4% in females).7

Age plays an important role, since adults aged 60 to 69 years have a higher risk of MS. A study conducted in adults over the age of 60 in Asia found prevalence rates of 34.8% in males and 54.1% in females.7 In addition to the above-mentioned differences, some studies show even larger discrepancies in prevalence: 8% in males in India, 24% in North American males, 7% in French females, and 43% in Iranian females.8

Apart from non-modifiable factors such as age and sex, MS involves modifiable risk factors associated with urbanization, such as a high frequency of overweight and poor dietary habits.9 Such factors are of great interest for public health worldwide, especially because of the current trend to increased overweight, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, dietary changes, and reduced physical activity. All this leads to increases in both abdominal obesity and other components of MS.10

A healthy lifestyle is essential to control and treat MS; this implies an appropriate diet,11,12 physical exercise,13 ideal weight, and smoking cessation. If these measures are insufficient, drug intervention is recommended for treating the constitutive factors of MS, provided agents14 which are effective for their specific indication (such as hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, etc.) but which do not increase insulin resistance are used.

MS has been known about since the 1980s. In the 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the current diagnostic criteria. Since then, there have been numerous publications on this condition. However, the profile of the available clinical trials concerning the disease—which can be useful to establish aspects such as those places with the highest number of publications, the main interventions assessed, the types of controls used, the number of patients evaluated, the outcome variables used, and the criteria used for the methodological quality of clinical trials—is currently unknown. These issues are important for understanding the most relevant features of experimental research conducted in patients with MS, and could be useful in orienting clinical guidelines, theoretical studies, new clinical trials, and other health care initiatives.

A systematic review was therefore designed to characterize the clinical trials related to the treatment of MS conducted from 1980 to 2015. A systematic review was decided upon because this type of study overcomes the limitations of individual studies (such as small population or sample size and low statistical power for their conclusions). Systematic reviews also have greater external validity as compared to individual studies because they include a larger number of patients and allow for characterizing interventions in a larger and more diverse population.15

MethodsType of study: systematic literature review.

Research protocol according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement16IdentificationA sensitive literature search was made in PubMed, ScienceDirect, and SciELO using seven search strategies with the following terms: “Metabolic syndrome X”, “Syndrome X”, “Plurimetabolic syndrome”, “Reaven Syndrome”, “Insulin resistance syndrome”, “Metabolic syndrome”, “Cardiac Syndrome X”, and their homologues in Spanish and Portuguese. The search was also conducted in the Cochrane Library.

Syntaxes used included: Metabolic syndrome X [Title/Abstract], TITLE-ABSTR-KEY (Plurimetabolic syndrome), Research>Reaven Syndrome [Resumo], and Metabolic syndrome: ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched).

The last search strategy (Cardiac Syndrome X) was included in order to increase the comprehensiveness of the protocol because the initial search found some review studies from the 1980s in which “Cardiac Syndrome X” and “Metabolic Syndrome X” were used as synonyms. However, at the selection stage, studies using the term “Cardiac Syndrome X” to refer to cardiac conditions rather than to MS were excluded.

Screening and selectionArticles whose title, abstract, or keywords contained the search term were considered eligible. The following inclusion criteria for complete review were applied to eligible articles: research published between 1980 and 2015; studies published in Spanish, English, or Portuguese; and original articles. Preclinical, observational, and theoretical (narrative or systematic reviews) studies, those with fewer than 10 subjects per arm, and those that did not describe the intervention applied were excluded. We also emailed the authors of some studies not available in the databases, and the literature references of the studies included were reviewed.

Evaluation of search reproducibility and information extractionThe researchers applied the research protocol independently to ensure the reproducibility of the review; discrepancies in results at this phase were resolved by consensus. The articles retrieved were entered into the Endnote Web program to identify and eliminate duplicate files. An Excel database was subsequently designed with the variables to be extracted from each included study, i.e., authors, title, publication year, study country, intervention applied, controls used, number of subjects in each arm, and outcome variables used. To ensure reproducibility, the information was extracted independently by two researchers.

Evaluation of methodological qualityThe following criteria were used to assess methodological quality: sample size calculation with explicit parameters of statistical power; the expected difference in the case of superiority trials or the absence of difference in non-inferiority trials; masking, blinding, inclusion and exclusion criteria; the type of data analysis, particularly the use of per protocol analysis when data loss was lower than sampling corrections, or by intention-to-treat in all other cases; and group homogeneity analysis in trials with two or more arms. For each study, the presence of the evaluated criterion scored 1, its absence scored 0, and studies where the criterion was not made explicit were classified NE.

Data analysisArticles were described using absolute and relative frequencies and 95% confidence intervals for proportions in the Epidemiological Analysis from Tabulated Data Program of the Pan-American Health Organization (EPIDAT) version 3.1.

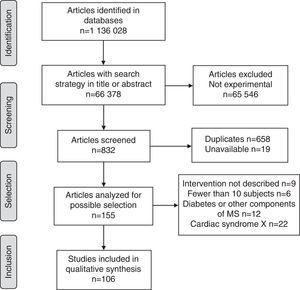

ResultsOverall, 1,136,028 publications were identified in all sources using the research strategies; of these, only 106 met the requirements of the research protocol (Fig. 1).

Of the studies included, 40.6% (95% confidence interval (CI)=30.7–50.4) were conducted in Europe, 33.0% (95% CI=23.6–42.4) in the Americas, 13.2% (95% CI=6.3–20.1) in the Western Pacific region, 4.7% (95% CI=1.6–10.7) in Southeast Asia, 4.7% (95% CI=1.6–10.7) in the Eastern Mediterranean, and 1.9% (95% CI=0.3–6.6) in Africa. The rest were multicenter studies. The countries with the largest number of published studies on MS were the United States, with 17 (48.6% of all studies in America), Italy, Spain, Turkey, and Germany (Fig. 2).

The proportion of studies published up to 2000 was 1.9% (95% CI=0.3–6.6), as compared to 2.8% (95% CI=0.6–8.0) in the 2001–2005 period, 20.8% (95% CI=12.6–28.9) in 2006–2010, and 74.5% (95% CI=65.8–83.3) in 2011–2015.

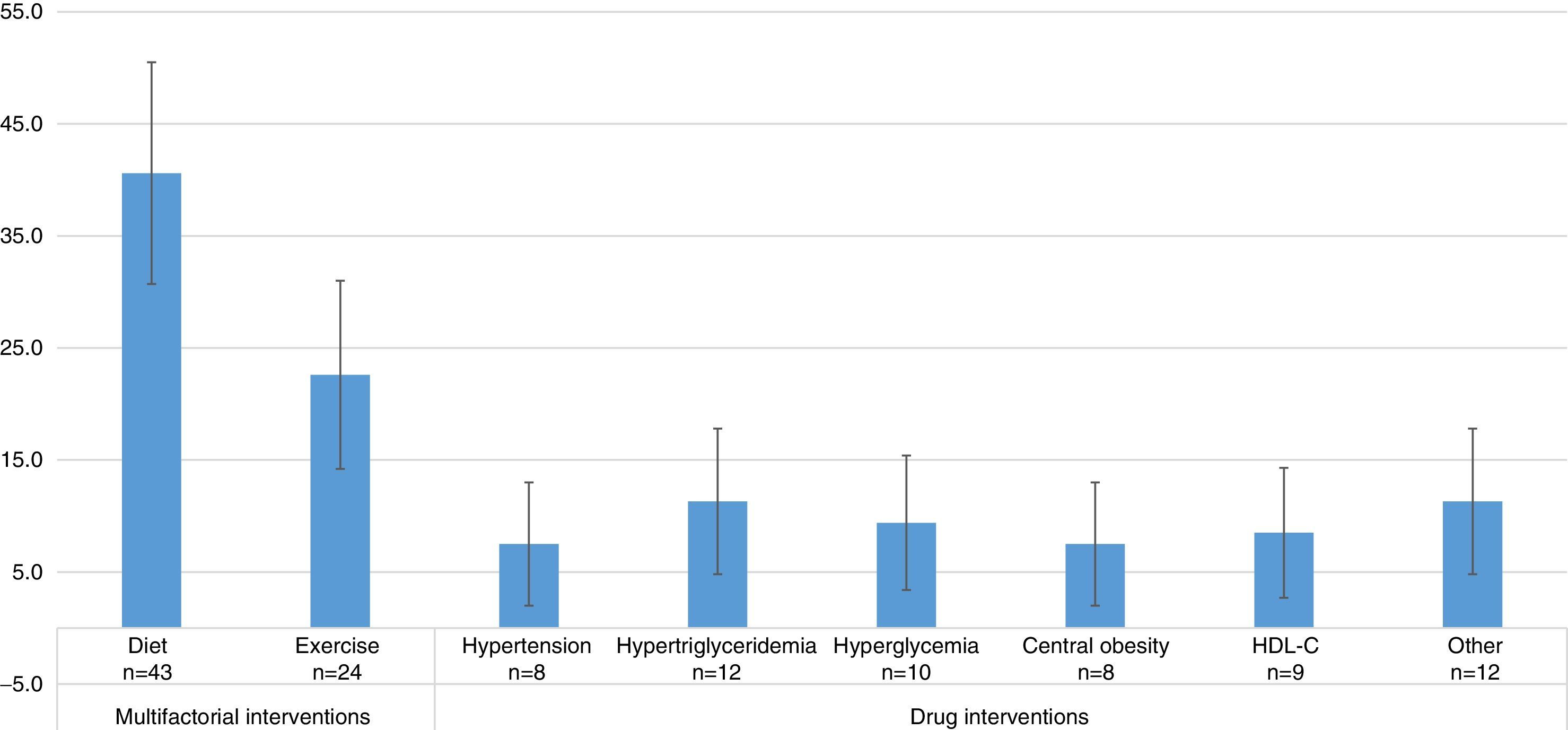

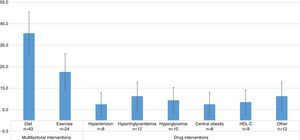

Studies evaluating dietary interventions were statistically more frequent than those evaluating drug interventions, and as frequent as those evaluating exercise-based treatments. The results were as follows: diet efficacy evaluation, 40.6% (95% CI=30.7–50.5); physical activity, 22.6% (95% CI=14.2–31.0); drugs for hypertension 7.5% (95% CI=2.0–13.0); for hypertriglyceridemia, 11.3% (95% CI=4.8–17.8); for hyperglycemia, 9.4% (95% CI=3.4–15.4); for central obesity, 7.5% (95% CI=2.0–13.0); and HDL-C, 8.5% (95% CI=2.7–14.3). In 11.3% (95% CI=4.8–17.8) of the studies, the effect of other interventions, including the use of antioxidants, vitamin D, niacin, antidepressant drugs, lactobacilli, and Ginkgo biloba was assessed (Fig. 3). Thus, multifactorial (those affecting several components of MS) or lifestyle interventions accounted for 63.2% of the interventions evaluated.

The most commonly used control was placebo, used in 54.7% (95% CI=44.8–64.7) of the studies, followed by diet (with modifications with respect to the treated arm) in 20.8% (95% CI=12.6–28.9), drugs in 14.2% (95% CI=7.0–21.3), and physical activity in 5.7% (95% CI=0.8–10.5), while 6.6% of the studies (95% CI=1.4–11.8) used no control.

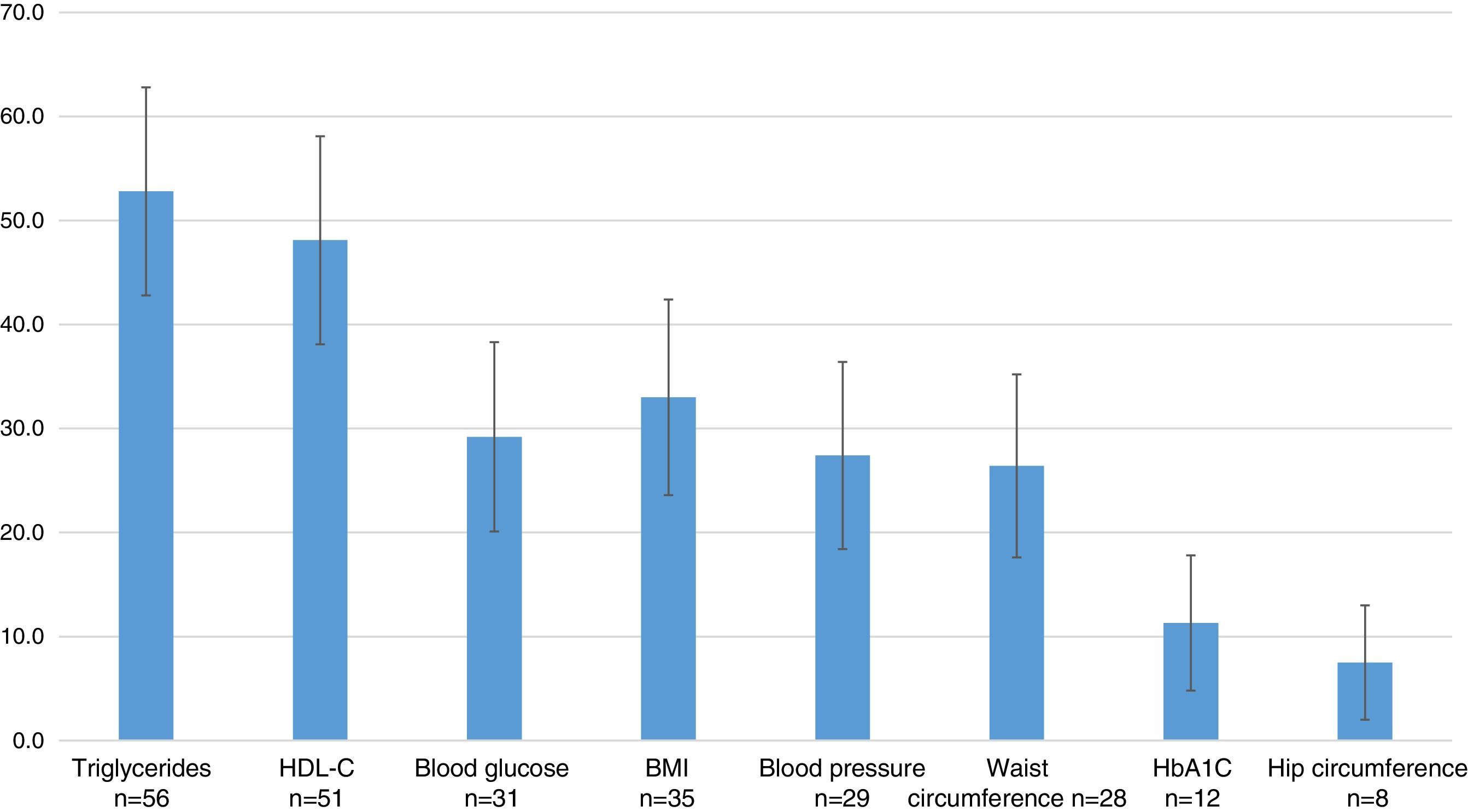

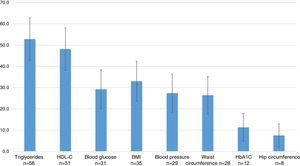

The most commonly used outcome variables were: measurements of triglycerides in 52.8% (95% CI=42.8–62.8), HDL-C in 48.1% (95% CI=38.1–58.1), the BMI in 33.0% (95% CI=23.6–42.4), blood glucose in 29.2% (95% CI=20.1–38.3), blood pressure in 27.4% (95% CI=18.4–36.4), waist circumference in 26.4% (95% CI=17.6–35.2), glycosylated hemoglobin in 11.3% (95% CI=4.8–17.8), and hip circumference in 7.5% (95% CI=2.0–13.0) (Fig. 4).

As regards the evaluation of methodological quality, no study met all of the defined criteria. A mean of 3.5 of the 8 criteria were met, suggesting a low methodological quality. The least reported (or applied) criteria were those related to sample size calculation and intention-to-treat analysis, while the more frequently reported were inclusion and exclusion criteria, although with a high variability between the studies, and random treatment assignment (in 86.8% of the studies).

The number of patients included in the 106 studies was 10,937 in the treatment groups, and 8384 in the control groups. Table 1 shows the percentage distribution of patients according to this review's variables. Ninety-seven percent of patients were in studies published after 2005; approximately 60% were included in multifactorial interventions (diet and physical activity), and more than 50% had triglycerides (59.0% of patients with intervention), HDL-C (55.2% of patients), and their BMI (53.5%) measured.

Number and proportions of patients included in the trials by independent variables included in the review.

| Patients No.=10,937 | Controls No.=8384 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Period | ||||

| Up to 2000 | 47 | 0.4 | 53 | 0.6 |

| 2001–2005 | 252 | 2.3 | 48 | 0.6 |

| 2006–2010 | 4430 | 40.5 | 2542 | 30.3 |

| 2011–2015 | 6208 | 56.8 | 5741 | 68.5 |

| Continent | ||||

| Americas | 5694 | 52.1 | 4436 | 52.9 |

| Europe | 3569 | 32.6 | 3041 | 36.3 |

| Western Pacific | 858 | 7.8 | 348 | 4.2 |

| Africa | 163 | 1.5 | 171 | 2.0 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 407 | 3.7 | 133 | 1.6 |

| Southeast Asia | 384 | 3.5 | 356 | 4.2 |

| Multifactorial intervention | ||||

| Exercise | 2460 | 22.5 | 1401 | 16.7 |

| Diet | 4037 | 36.9 | 4005 | 47.8 |

| Pharmacologic intervention for one factor | ||||

| Hypertension | 634 | 5.8 | 675 | 8.1 |

| Hyperglycemia | 428 | 3.9 | 330 | 3.9 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 332 | 3.0 | 324 | 3.9 |

| Central obesity | 2268 | 20.7 | 551 | 6.6 |

| Low HDL | 258 | 2.4 | 266 | 3.2 |

| Other | 1183 | 10.8 | 1444 | 17.2 |

| Placebo | 6663 | 60.9 | 4050 | 48.3 |

| Control | ||||

| Exercise | 604 | 5.5 | 598 | 7.1 |

| Diet | 2310 | 21.1 | 2520 | 30.1 |

| Drug | 1122 | 10.3 | 1147 | 13.7 |

| None | 340 | 3.1 | 128 | 1.5 |

| Outcome variable | ||||

| Blood glucose | 4104 | 37.5 | 2389 | 28.5 |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin | 857 | 7.8 | 633 | 7.6 |

| Blood pressure | 2432 | 22.2 | 2249 | 26.8 |

| Triglycerides | 6452 | 59.0 | 3740 | 44.6 |

| HDL-C | 6038 | 55.2 | 3347 | 39.9 |

| Waist circumference | 4806 | 43.9 | 1711 | 20.4 |

| BMI | 5848 | 53.5 | 2709 | 32.3 |

| Hip circumference | 1073 | 9.8 | 685 | 8.2 |

| Other | 3371 | 30.8 | 2607 | 31.1 |

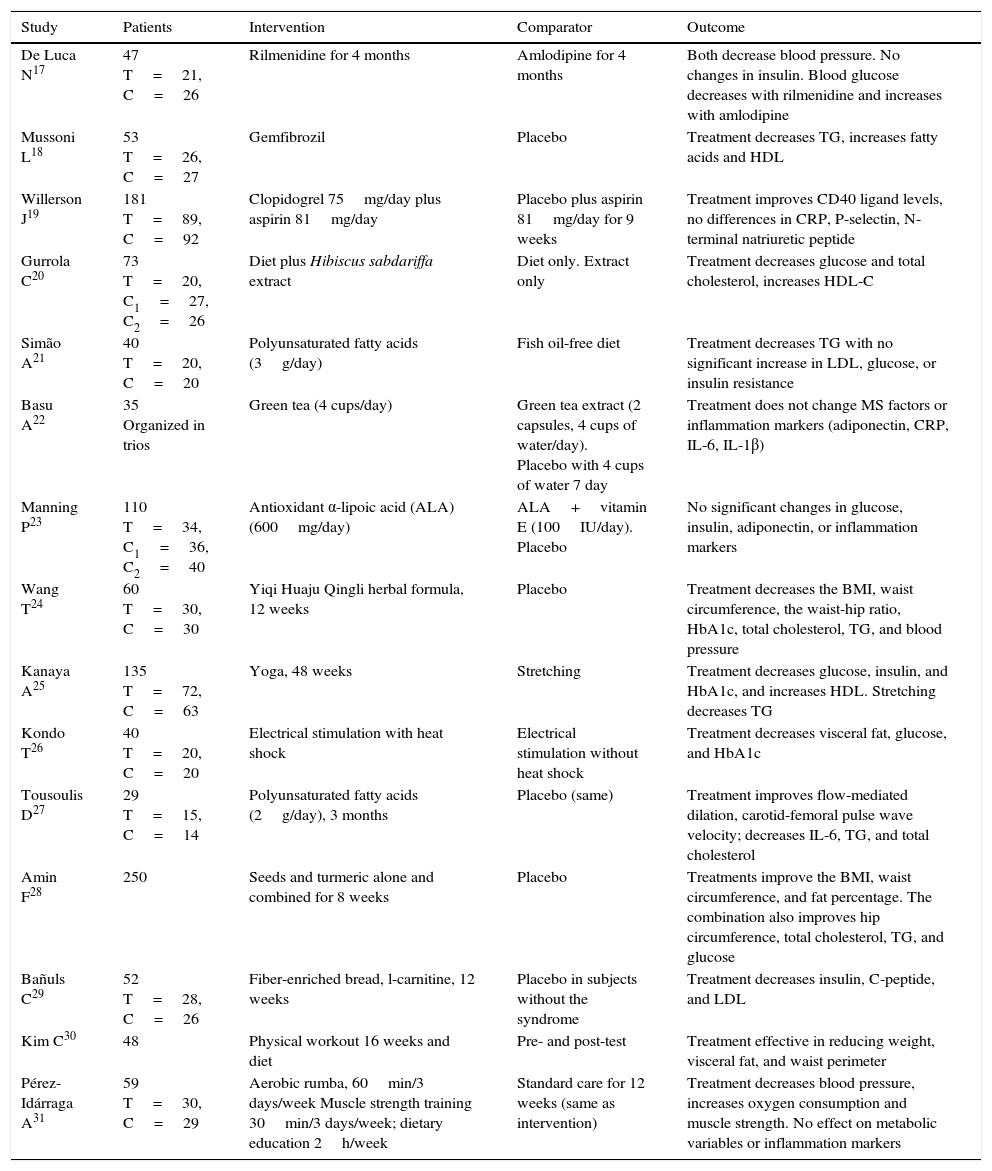

Table 2 shows the elements of the PICO (Patient-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome) question regarding some clinical trials that evaluated various interventions. All the studies were of individuals with MS. In some studies, the population had additional features such as obesity, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and glucose intolerance17 or microalbuminuria.24 Regarding their efficacy, drug interventions for one component of MS showed results such as blood pressure reduction by antihypertensives17 or the effects of triglycerides.18 Diet combined with natural extracts also showed good efficacy for different variables such as glucose, total cholesterol, HDL-C,20 glycosylated hemoglobin, the BMI, and waist circumference.24 Physical therapies also proved effective for one or more components of MS (Table 2).

Description of clinical trials with different interventions to manage MS according to PICO questions.

| Study | Patients | Intervention | Comparator | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Luca N17 | 47 T=21, C=26 | Rilmenidine for 4 months | Amlodipine for 4 months | Both decrease blood pressure. No changes in insulin. Blood glucose decreases with rilmenidine and increases with amlodipine |

| Mussoni L18 | 53 T=26, C=27 | Gemfibrozil | Placebo | Treatment decreases TG, increases fatty acids and HDL |

| Willerson J19 | 181 T=89, C=92 | Clopidogrel 75mg/day plus aspirin 81mg/day | Placebo plus aspirin 81mg/day for 9 weeks | Treatment improves CD40 ligand levels, no differences in CRP, P-selectin, N-terminal natriuretic peptide |

| Gurrola C20 | 73 T=20, C1=27, C2=26 | Diet plus Hibiscus sabdariffa extract | Diet only. Extract only | Treatment decreases glucose and total cholesterol, increases HDL-C |

| Simão A21 | 40 T=20, C=20 | Polyunsaturated fatty acids (3g/day) | Fish oil-free diet | Treatment decreases TG with no significant increase in LDL, glucose, or insulin resistance |

| Basu A22 | 35 Organized in trios | Green tea (4 cups/day) | Green tea extract (2 capsules, 4 cups of water/day). Placebo with 4 cups of water 7 day | Treatment does not change MS factors or inflammation markers (adiponectin, CRP, IL-6, IL-1β) |

| Manning P23 | 110 T=34, C1=36, C2=40 | Antioxidant α-lipoic acid (ALA) (600mg/day) | ALA+vitamin E (100IU/day). Placebo | No significant changes in glucose, insulin, adiponectin, or inflammation markers |

| Wang T24 | 60 T=30, C=30 | Yiqi Huaju Qingli herbal formula, 12 weeks | Placebo | Treatment decreases the BMI, waist circumference, the waist-hip ratio, HbA1c, total cholesterol, TG, and blood pressure |

| Kanaya A25 | 135 T=72, C=63 | Yoga, 48 weeks | Stretching | Treatment decreases glucose, insulin, and HbA1c, and increases HDL. Stretching decreases TG |

| Kondo T26 | 40 T=20, C=20 | Electrical stimulation with heat shock | Electrical stimulation without heat shock | Treatment decreases visceral fat, glucose, and HbA1c |

| Tousoulis D27 | 29 T=15, C=14 | Polyunsaturated fatty acids (2g/day), 3 months | Placebo (same) | Treatment improves flow-mediated dilation, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; decreases IL-6, TG, and total cholesterol |

| Amin F28 | 250 | Seeds and turmeric alone and combined for 8 weeks | Placebo | Treatments improve the BMI, waist circumference, and fat percentage. The combination also improves hip circumference, total cholesterol, TG, and glucose |

| Bañuls C29 | 52 T=28, C=26 | Fiber-enriched bread, l-carnitine, 12 weeks | Placebo in subjects without the syndrome | Treatment decreases insulin, C-peptide, and LDL |

| Kim C30 | 48 | Physical workout 16 weeks and diet | Pre- and post-test | Treatment effective in reducing weight, visceral fat, and waist perimeter |

| Pérez-Idárraga A31 | 59 T=30, C=29 | Aerobic rumba, 60min/3 days/week Muscle strength training 30min/3 days/week; dietary education 2h/week | Standard care for 12 weeks (same as intervention) | Treatment decreases blood pressure, increases oxygen consumption and muscle strength. No effect on metabolic variables or inflammation markers |

IL: interleukin; CRP: C-reactive protein; TG: triglycerides.

Metabolic syndrome has been known about since the 1980s. The current diagnostic criteria were established by the WHO in the 1990s. Despite multiple trials over more than 30 years, only developed countries such as the United States and some European Union countries, such as Italy and Spain, have produced frequent publications of clinical trials of interventions for this condition. The reason for this may be the epidemiological profile seen in some of those places, as the WHO has reported that obesity and dyslipidemia account for a considerable disease burden in those countries.32

Data supporting the above include WHO reports that more than 75% of women over the age of 30 years in the United States, Mexico, Jamaica, and Nicaragua are overweight, and more than 75% of men over 30 years of age in the United States, Germany, Greece, and the United Kingdom are obese.32

By contrast, in some countries the number of publications of clinical trials is minimal, and evidence of different interventions for MS is required. This applies particularly to areas such as Central America, South America, Africa, and Asia, which despite having a high prevalence of MS (20%–40%) have a low rate of experimental research on the efficacy of different therapeutic options.33

On the other hand, it soon became clear that most studies were concentrated over the past five years—which implies that clinical trials for this disease are relatively recent—and were of poor methodological quality (most studies did not make their quality criteria explicit). Poor methodological quality was not an exclusion criterion for this review because the main goal was to characterize the profile of publications, with quality criteria being included as additional variables for the analysis.

Only 50% of the studies assessed the effect of multifactorial interventions; this is a limitation because for the syndrome it is desirable for clinical trials to evaluate interventions with effects on central obesity and at least two defining conditions of the disease. Otherwise, the studies may be specific for hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperglycemia, or some other component, but not for MS itself. López et al. agree with this by suggesting that the prevention and management of MS should be multifactorial and targeted to the different risk factors that define the syndrome.34

Physical activity and diet stand out among the multifactorial interventions. The former has positive effects on blood glucose control, lipid profile, visceral adipose tissue, and other components of MS, and has as added advantages the usually short intervention times (about six weeks),35 the simple facilities required for implementation, and a high safety level when physical activity is supervised. However, the challenges associated with exercise intensity and in motivating patients to incorporate it into their daily routines should not be overlooked.36

Dietary interventions have yielded significant improvements in cardiovascular disease risk factors, and positive effects on blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, lipid profile, lipoproteins, inflammation, oxidative stress, and carotid atherosclerosis.37 However, it should be kept in mind that dietary interventions may impose much greater demands than physical activity, as they require longer application times and costs, and in some cases the food is not readily accepted or available in some contexts and populations.38

Finally, drug interventions focus on a single component of MS, and are therefore effective for the targeted factor, but have no satisfactory effects on the other components. In other words, they make no significant impact on the multifactorial nature of the syndrome, particularly on the central obesity component.

Most studies used placebo as a control. This is a controversial issue in clinical trials because while some advocate its use because it provides a more accurate and faster response regarding treatment efficacy and safety, others question it for ethical reasons. The situations in which the use of placebo is ethically acceptable include the absence of effective treatment, short-term use, and trials with a duration that would not increase the risks related to the underlying disease or cause additional damage or irreversible losses.39

The limitations of this study include the fact that comprehensive evaluation of the methodological quality was not possible due to the high variability in the reports regarding the methodologies used, and in the results of the studies included; this is probably the result of the very wide time window used in this review. Moreover, many studies did not elaborate on their design in a way that allowed for their classification according to objectives (phase I, II, III, or IV), methods (controlled or not), treatment structure (parallel, sequential, factorial, of equivalence, etc.), and type of assignment (fixed, dynamic, adaptive), among other characteristics of clinical trials. In fact, these limitations could lead to recommendations for improving the reporting of clinical trials in MS.

In conclusion, studies on the efficacy of treatments for MS are scarce and have mainly been conducted in the past five years and in high-income countries. Few trials are available on interventions affecting three or more factors and assessing several outcomes. Lifestyle interventions (diet and physical activity) emerge as the most important for managing this multifactorial syndrome.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cardona Velásquez S, Guzmán Vivares L, Cardona-Arias JA. Caracterización de ensayos clínicos relacionados con el tratamiento del síndrome metabólico, 1980-2015. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2017;64: 82–91.