To evaluate the efficacy and safety of one single-session of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) performed in thyroid benign and predominantly solid nodules.

Patients and methodsUnicentric retrospective study in usual clinical setting that included patients with solid and benign thyroid nodules treated with one single session of RFA and with follow-up of at at least 6 months after the procedure. RFA was performed as an alternative to surgery in cases of pressure symptoms or nodular growth evidence. Patients were evaluated basally and at one, 3 and 6 months after RFA and also at twelve months if the follow-up was available. In each evaluation efficacy variables were recorded (percentual change from basal volume, percentage of nodules reaching a volume reduction above 50% from baseline, patients with disappearance of pressure symptoms and the possibility of antithyroid drug withdrawal) and safety variables were also registered including minor complications (pain needing analgesic drugs, hematoma) and major complications (voice changes, braquial plexus injury, nodule rupture and thyroid dysfunction).

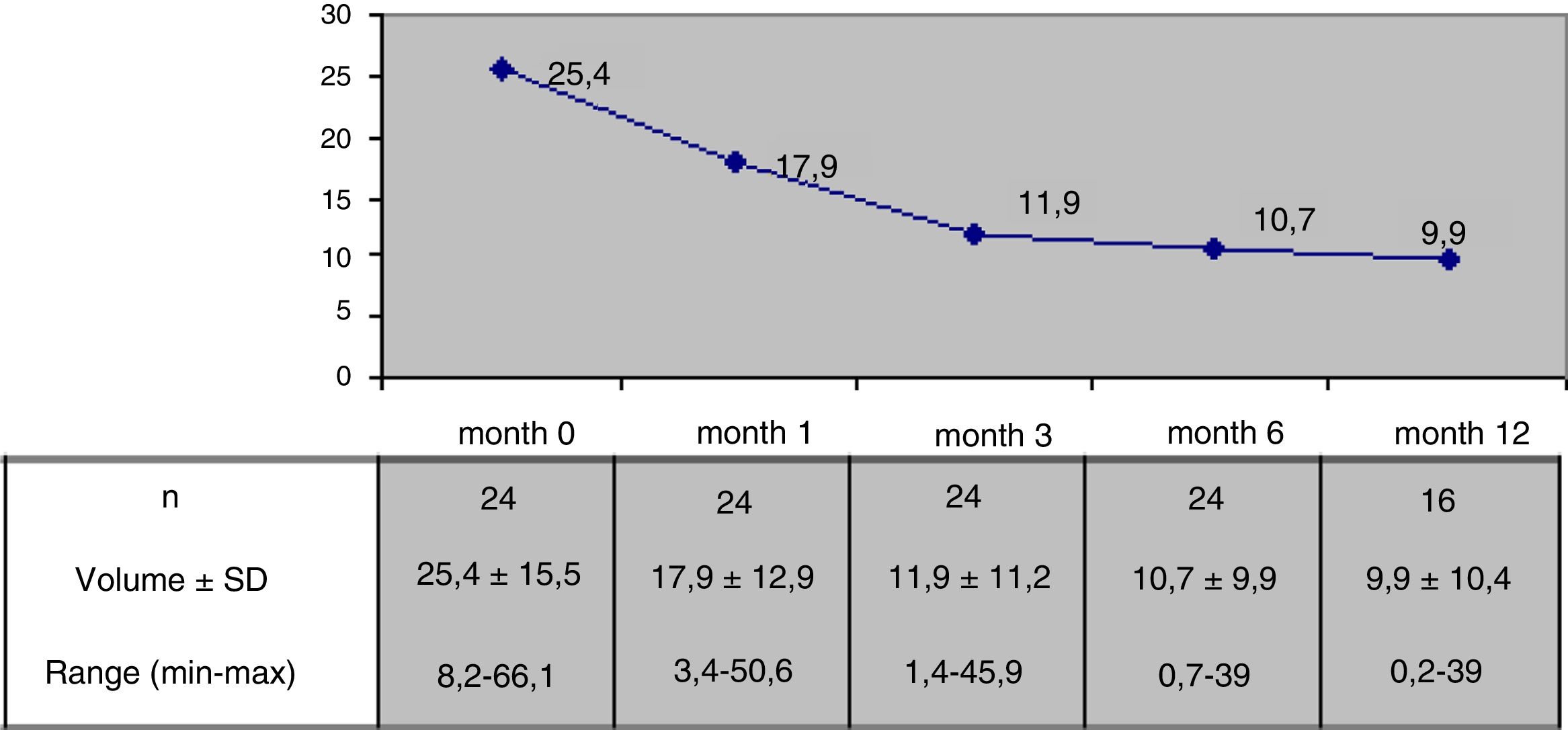

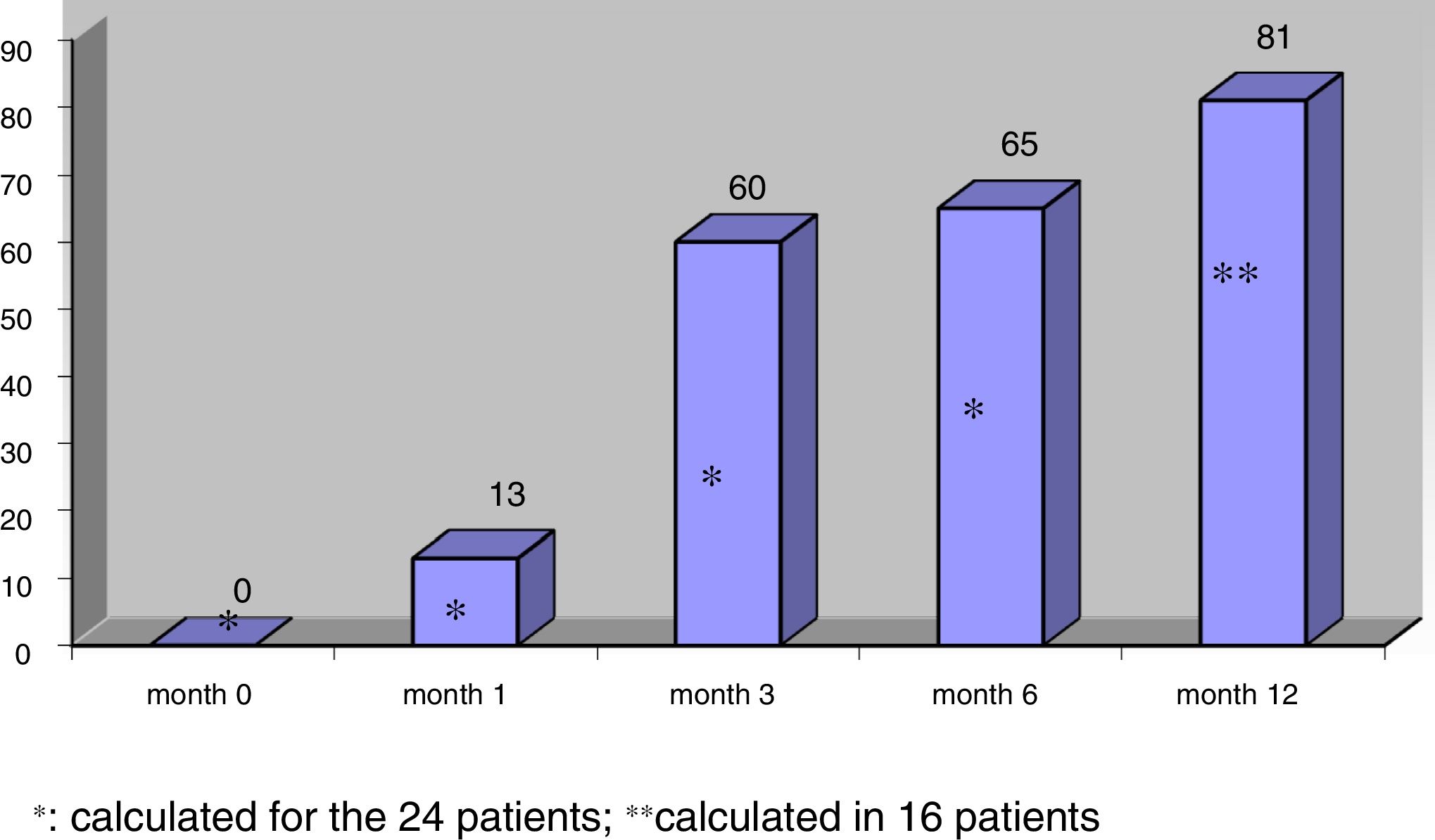

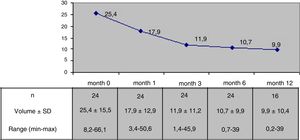

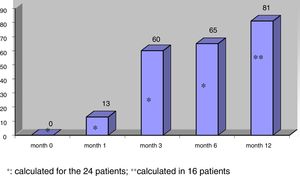

Results24 patients with a follow-up of at least 6 months after RFA were included, 16 of them with more than 12 months of follow-up. Mean nodule volume changed from 25.4 ± 15.5 ml basally to 10.7 ± 9.9 ml at month 6 (p < 0,05) and to 9.9 ± 10,4 ml at month 12 in 16 nodules. 6 months after RFA mean volumetric reduction was 57.5 ± 24% and 65% of the nodules reached a volume reduction above 50% from baseline. Median percentage of reduction at month 6 was 50.4 ± 25.7% for nodules with a basal volume above 20 ml (n = 13) and 65.3 ± 20.1% for nodules with a lower basal volume (n = 11). Pressure symptoms reported in 12 patients disappeared in all cases. Antithyroid drugs could be stopped in 3 of 4 cases treated before RFA. A mild and transient pain responsive to conventional analgesic drugs was recorded in 9 patients during the 24 h after the procedure and in 7 a small perithyroid and transient hematoma was observed in the 48 following hours. One major complication was described as a nodule rupture that recovered spontaneously. There were no changes in hormonal values in euthyroid cases.

ConclusionA single session of RFA seems to be an effective and safe procedure in patients with solid thyroid nodules with pressure symptoms or relevant growth evidence. As an outpatient and scarless procedure with no need of general anaesthesia it could become an useful alternative to lobectomy when surgery is refused or in patients at high surgical risk.

Valorar la eficacia y seguridad de una sesión única de ablación por radiofrecuencia (ARF) en pacientes con nódulos tiroideos benignos y de predominio sólido.

Pacientes y métodoEstudio unicéntrico retrospectivo de práctica clínica habitual en el que se incluyeron pacientes con nódulos tiroideos sólidos benigno sometidos a una sesión única de ARF con seguimiento de al menos 6 meses tras procedimiento indicada como alternativa a la cirugía por presentar clínica local compresiva y/o evidencia de crecimiento nodular. Los pacientes fueron evaluados antes, al mes, 3 meses, 6 meses de la ARF así como a los 12 meses en aquellos son seguimiento disponible. En cada evaluación se recogieron variables de eficacia (cambio porcentual del volumen nodular, el porcentaje de nódulos con reducción volumétrica mayor al 50% respecto al volumen inicial, la desaparición de los síntomas de compresión y posibilidad de retirar la medicación antitiroidea en aquellos casos bajo tratamiento) y variables de seguridad incluyendo complicaciones menores (dolor que precisó de analgesia convencional, hematoma peritiroideo de reabsorción espontánea) y complicaciones mayores (cambios en la voz, daños en el plexo cervical, ruptura nodular, disfunción tiroidea).

ResultadosSe describen los resultados en 24 pacientes con seguimiento de hasta 12 meses en 16 de ellos. El volumen nodular medio pasó de 25,4 ml ± 15,5 ml antes de la ARF a 10,7 ± 9,9 ml a los 6 meses (p < 0,05) y a 9,9 ml ± 10,4 ml a los 12 meses (en 16 casos evaluados) resultando la reducción porcentual de volumen significativa desde el mes siguiente al procedimiento. A los 6 mesesla reducción media alcanzada fue del 57,5 ± 24% y el 65% de los nódulos presentaban una reducción de volumen mayor al 50%. En aquellos nódulos con volumen inicial mayor a 20 ml (n = 13) la reducción porcentual a los 6 meses fue del 50,4 ± 25,8% frente a 65,3 ± 20,1% en los nódulos de menor volumen inicial (n = 11). La sintomatología compresiva desapareció desde el primer mes en los 12 pacientes que la referían. La medicación antitiroidea pautada antes de la ARF en 4 casos pudo ser retirada en 3. En 9 pacientes se registró la presencia de dolor leve transitorio en las primeras 24 h que respondió a analgésicos convencionales y en 7 se objetivó un pequeño hematoma peritiroideo de reabsorción espontánea en la ecografía de control a las 24 a 48 h de la ablación. Se observó al mes de la ARF, un caso de ruptura nodular que se resolvió de manera espontánea. No se apreciaron cambios en los valores hormonales en los pacientes eutiroideos.

ConclusiónUna sesión única de ARF parece un tratamiento eficaz y seguro en pacientes portadores de nódulos tiroideos benignos sólidos y con clínica compresiva y/o evidencia de crecimiento nodular relevante. Al ser un procedimiento ambulatorio sin necesidad de anestesia general y sin precisar de incisión cutánea podría convertirse en una alternativa útil a la cirugía en los casos en que ésta se halle rechazada o se considere de alto riesgo.

Despite their high frequency,1 the usually benign nature of thyroid nodules (the exception being 5–15% of all cases)2,3 allows for ultrasound follow-up of most patients with thyroid nodules. Follow-up seeks to detect a minority of malignant nodules not initially identified, and to detect significant growth of some benign nodules or the appearance of symptoms secondary to the compression of adjacent anatomical structures.4 Significant growth during follow-up and the occurrence of compressive symptoms, while uncommon (seen in approximately 5% of all cases),5 require treatment.4 Percutaneous ethanol injection is the recommended treatment4,6 in predominantly cystic compressive nodules and lesions that recur after evacuating puncture. In predominantly solid compressive nodules, most guides4,7 advise surgery with lobectomy or total thyroidectomy (depending on the coexistence of contralateral nodules). The limited efficacy of ethanol injection in predominantly solid nodules8 has led to the evaluation of the usefulness of minimally invasive thermal ablation techniques.9 One of these techniques is radiofrequency ablation (RFA). This technique involves heat-induced coagulative tissue necrosis in a predictable area around the active tip of an electrode inserted percutaneously into the thyroid nodule and connected to an external alternating current radiofrequency (RF) generator. Radiofrequency ablation does not require hospital admission, general anesthesia or skin incision.10

In different series, RFA has achieved significant reductions in nodule volume 6 months after the procedure11,12 (51–93%), together with a marked improvement or the disappearance of the associated clinical manifestations and improved aesthetic outcomes. The good results obtained with this outpatient procedure, and its few adverse effects13 have led scientific bodies in some countries14,15 to recommend the application of RFA to solid thyroid nodules causing compressive or aesthetic problems, usually as an alternative to surgery when the latter is rejected by the patient, or in individuals considered to be at high risk.

The purpose of the study was to assess the efficacy and safety of a single RFA session in patients with predominantly solid benign thyroid nodules not amenable to surgery.

Material and methodsRadiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules was included in the services portfolio of the Department of Radiodiagnosis of Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain) in April 2016. This technique is only proposed as an alternative to surgery in patients who refuse surgery or when surgery is considered to pose a high risk for the patient. Radiofrequency ablation is indicated by the Endocrinology Department in patients with predominantly (>50%) solid thyroid nodules in which two fine needle puncture cytology studies indicate the presence of Bethesda class II lesions,16 together with local compressive clinical signs attributed to the nodule (dysphonia, dyspnea, dysphagia or foreign body sensation) or with evidence of growth during follow-up (an increase in volume of >50% or an increase of ≥2 mm in at least two of the diameters). Patients with initial thyroid hyperfunction receive antithyroid drugs to normalize their hormone levels before ablation is performed. The Radiology Department in turn excludes cases presenting intrathoracic nodules with small chances of success from the technical perspective. All subjects are required to sign an informed consent form addressing the technique and its potential complications.

PatientsThe present study comprised patients with thyroid nodules subjected to a single RFA session (representing all the patients undergoing RFA at our center) from the introduction of the technique in April 2016 to November 2018, and with a mean follow-up of at least 6 months. Patients were selected from a weekly monographic thyroid nodule clinic. The patient evaluations were made before RFA (month 0) and at months 1, 6 and 12 after ablation. Efficacy and safety variables were compiled at each evaluation.

The efficacy variables included nodule volume (in ml) (calculated using the formula: abcπ / 6, where a = anteroposterior diameter in cm, b = transverse diameter in cm, and c = longitudinal diameter in cm); percentage reduction in nodule volume from month 0 ([initial volume – final volume] / initial volume × 100); the proportion of nodules with therapeutic success (defined as a decrease in volume of ≥ 50%17); the proportion of cases in which compression symptoms disappeared; and the possibility of discontinuing antithyroid drugs in patients previously treated with such drugs.

Recording of the safety variables included major and minor complications. Major complications included dysphonia, nodule rupture, brachial plexus damage, and changes in thyroid function. Spontaneously reabsorbing intra-thyroid, subcapsular and peri-thyroid hematomas were regarded as minor complications. Pain leading to suspension of the procedure and pain requiring analgesic treatment after the procedure were also regarded as minor complications. Pain or discomfort not requiring analgesia was considered to be an adverse effect, not a complication.

ProcedureRadiofrequency ablation was performed by two radiologists experienced in thyroid puncture at our center and trained in the RFA of thyroid nodules. The technique was performed on an outpatient basis after the conscious sedation of the subject with midazolam and under local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine (at the puncture site and around the thyroid capsule). An electrode with a self-cooling active tip (Star RF electrode, 18 G with a 7 mm active tip) was inserted via the trans-isthmus route to the target nodule. The electrode in turn was connected to an external alternating current radiofrequency generator (VIVA RF System, Starmed). After the insertion of the electrode tip into the deepest zone of the nodule, ablation was performed under ultrasound guidance using the moving-shot technique,18 displacing the electrode towards more superficial areas as the deeper zones were necrotized (demonstrated by the appearance of transient hyperechogenic segments and changes in tissue impedance). After completing the procedure, the patients remained under observation with the local application of ice, and were discharged following ultrasound monitoring 2/3 h after RFA, with the prescription of analgesia if needed (paracetamol and/or metamizol). The patients underwent ultrasound evaluation after 24–48 h to determine the possible presence of intra-thyroid or peri-thyroid hematomas, with the recording of potential adverse effects or complications.

Statistical analysisThe characteristics of the patients and nodules at month 0 were described based on the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and percentages for qualitative variables. The Student t-test for related samples was used to compare mean values at the different timepoints versus month 0. Statistical significance was considered for p < 0.05. The SPSS version 15 statistical package was used throughout.

ResultsThe patients eligible for RFA were selected from a monographic thyroid nodule clinic where a total of 672 patients were evaluated during the study period. In this time, 28 patients with thyroid nodules underwent single-session RFA. These 28 individuals represented all the patients subjected to RFA for thyroid nodules at our center at the time of the writing of this study. Four patients with a follow-up of less than 6 months were excluded. Therefore, we report the results of 24 patients (6 males) with a mean age of 60 ± 13 years and a minimum follow-up of 6 months. Sixteen of these patients had a follow-up of 12 months after the procedure.

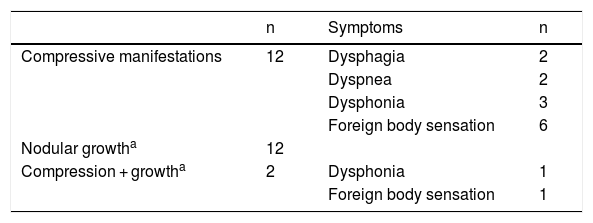

Radiofrequency ablation was indicated due to local compressive clinical manifestations in 12 subjects, evidence of nodular growth in 12 patients, and the coexistence of both compression and growth in two subjects (Table 1). Four patients received antithyroid drugs (one with toxic adenoma and 3 with pre-toxic multinodular goiter) to secure euthyroid status before RFA.

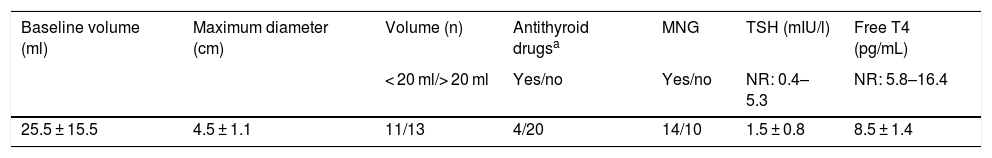

The nodules had an initial or baseline (month 0) mean volume of 25.4 ± 15.5 ml (range: 8.2–66.1 ml) and a mean maximum size of 4.5 ± 1.1 cm (range: 1.9–7 cm). In 13 cases (54.2%) the initial volume was >20 ml. In these 13 patients, the initial nodule volume was 34.9 ± 15.6 ml (range: 20.6–66.1 ml), and in nodules with an initial volume < 20 ml (n = 11), the mean baseline volume was 14.2 ± 2.7 ml (range: 8.2–17.5 pg/ml). The mean baseline nodule volume in the four hyperthyroid patients was similar to that of the euthyroid patients (23,7 ± 11.9 ml and 25.8 ± 16.4 ml respectively, p > 0.05). The mean initial volume of the nodules subjected to RFA due to local compressive clinical manifestations in 14 patients (28.4 ± 15.4 ml) was similar to that of the nodules in patients subjected to RFA due to evidence of prior growth only (22.5 ± 15.3 ml). Table 2 summarizes the baseline (month 0) characteristics of the patients.

Baseline characteristics of the thyroid nodules.

| Baseline volume (ml) | Maximum diameter (cm) | Volume (n) | Antithyroid drugsa | MNG | TSH (mIU/l) | Free T4 (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 20 ml/> 20 ml | Yes/no | Yes/no | NR: 0.4–5.3 | NR: 5.8–16.4 | ||

| 25.5 ± 15.5 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 11/13 | 4/20 | 14/10 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 8.5 ± 1.4 |

MNG: multinodular goiter; NR: normal range.

The mean nodule volume decreased significantly from 25.4 ± 15.5 ml at month 0 to 10.7 ± 9.9 ml (range: 0.7–39 ml) at month 6 (n = 24) and 9.9 ± 10.4 ml (range: 0.2–39 ml) at month 12 (in 16 nodules); p < 0.01. The mean nodule volume during follow-up is shown in Fig. 1. The percentage reduction in volume with respect to baseline (month 0) proved significant from month 1 (reduction 31.5 ± 18.1%; range: 0–71%), when the decrease was greatest, and continued at month 3 (52.7 ± 25.2%; range: 0–86%), month 6 (57.5 ± 23.9%; range: 3.2–92%) and month 12 (65.4 ± 20.7%; range: 29.1–98.7%). The percentage of nodules in which therapeutic success was achieved increased progressively to 66% at month 6 (n = 24 nodules) and 81.2% at month 12 (n = 16 nodules evaluated), as shown in Fig. 2.

No significant differences were found in percentage volume reduction observed at 6 and 12 months between nodules with an initial volume of <20 ml and those of greater volume (65.3 ± 20.1% [range: 21.4–92.1] versus 50.4 ± 25.5% [range: 3.2–86.9]; p > 0.05 at 6 months and 72.4 ± 19.7% [range: 37.2–98.7] versus 56.5 ± 19.5% [range: 29.1–91.9]; p > 0.05 at 12 months, in nodules initially smaller and larger than 20 ml, respectively). At both 6 and 12 months, the coefficient of variation of percentage volume reduction was lower in nodules with an initial volume <20 ml than in those of greater volume (31% versus 51% at 6 months, and 27% versus 35% at 12 months, respectively; p < 0.05). Likewise, no statistically significant differences were seen in percentage treatment success between the smaller and larger nodules (at 6 months: 81.8% for nodules <20 ml initial volume versus 53.8% for nodules of greater volume; p > 0.05). On comparing the first 10 nodules in chronological order subjected to RFA versus the subsequently treated 14 nodules, no differences were observed in the final percentage reduction achieved or in percentage treatment success (p > 0.05).

The compressive symptoms reported by 12 patients disappeared from month 1 in all cases. There were no differences in the mean volume reached or in percentage treatment success between nodules subjected to RFA due to compression signs and those treated only due to evidence of prior growth (p > 0.05).

Antithyroid drugs could be discontinued in 3/4 cases at month 3, due to the normalization of thyroid function. There were no differences in the mean volume reached or in percentage treatment success at 6 and 12 months between hyperthyroid individuals and the other patients (p > 0.05).

Safety variablesRadiofrequency ablation was well tolerated by all patients, and in no case was discontinuation of the procedure required. Following RFA, 9 patients reported transient mild local pain (requiring conventional analgesia in the first 24 h), and in 7 cases spontaneously reabsorbing minimal hematomas were identified at control ultrasound performed 24/48 h after ablation. We recorded only one major complication in the form of nodular rupture found by ultrasound at month 1, in a patient who reported a sudden increase in neck volume after Valsalva maneuvering, and which resolved spontaneously. There were no changes in serum TSH or free T4 levels at any timepoint versus baseline, except for the normalization of TSH and free T4 in three of the four patients with prior hyperthyroidism.

DiscussionMany series have described the efficacy and safety of minimally invasive techniques such as RFA in its application to solid and compressive benign thyroid nodules.12 The results of Korean and Italian pioneering centers stand out in this respect. Nevertheless, RFA has not yet been unanimously included in all international guides on the standard management of thyroid nodules.4 The efficacy of RFA can be assessed based on different parameters such as percentage volume reduction, the proportion of nodules with therapeutic success (volume reduction > 50%), and the reduction or disappearance of compression symptoms.18

The results of our study show improvements to all three of these parameters, with a mean volume reduction of 57% at 6 months after single-session RFA. This figure is similar to that reported by some authors,19 but is lower than in other series that report reductions of up to 96%.20 Treatment success (defined as volume reduction > 50%18,20) was achieved at 6 months in 66% of the cases, and in a larger percentage of cases followed-up on for 12 months. As in other studies,21 volume reduction was greatest in the early stages, at one month after RFA, followed by a more gradual decrease at 6 and 12 months.21,22 The decrease in volume, which proved significant from month 1, was accompanied by the early disappearance of compressive symptoms. The efficacy of the technique according to local clinical practice is consistent with that reported in many publications,11,12 with improvements in the scores used to assess compression symptoms. Most studies agree that maximum volume reduction is observed between 6–12 months after the procedure,23 though the reduction achieved varies greatly among centers from 44.6%24 to over 90%.20,25 The disparity in the results regarding percentage volume reduction and percentage treatment success is attributable to different factors, such as the RFA technique used (moving-shot technique versus fixed electrode technique), the experience of the operating team, the follow-up time, the characteristics of the nodule (initial size, composition), and the number of radiofrequency sessions involved.

Thus, with the introduction of the moving-shot technique,26 compared to the older fixed electrode techniques,27 improvements have been seen in terms of efficacy, such as the volume reduction achieved at 6 months (between 72–84% with moving shot techniques versus 46–68% with fixed electrode techniques).12 In series from experienced centers with long follow-up periods after RFA, volume reductions > 90% from baseline have been reported,22 and in some cases efficacy is seen to increase as team experience improves.28 With regard to the influence of the nodule characteristics upon the efficacy of RFA (not considered in our study), some authors suggest a lesser cystic component14,29 and greater volume11 to be associated with poorer outcomes. In the case of larger nodules (>20 ml), more than one RFA session may be required in order to achieve percentage reductions similar to those achieved with smaller nodules subjected to single-session RFA.30 The mean baseline nodule volume in our study (>20 ml) was conspicuously greater than in other series such as that of Jeong et al.26 (mean volume 6 ml), and could partly explain the lesser volume reduction achieved at 6 months (57% in our study versus 85% in the aforementioned series), as well as the lower treatment success rate at 6 months (65% and 91%, respectively). However, we observed no significant differences in the efficacy results between nodules measuring < 20 ml in volume and those of larger size. This is possibly related to the sample size, since the absolute values in each subgroup tend to reflect different efficacy according to the baseline volume. In large volume nodules, and in agreement with other studies,31 the observed greater coefficient of variation in percentage volume reached suggests that the efficacy of RFA varies greatly from nodule to nodule, and that this causes the outcome of the technique to be unpredictable in such cases. Although our study recorded no significant differences in the efficacy outcomes between the first and last nodules subjected to RFA, the coefficient of variation was greater than in other studies,31 demonstrating a possible association with the learning curve. The fact that RFA was performed by two radiologists could have influenced the lack of a perceived improvement of the outcomes with increasing operator experience in such a limited sample of subjects. Furthermore, and in contrast to our own protocol, the regular protocols used in other centers26,29 include the possibility of repeating RFA with a new session if the compressive manifestations persist, or if ultrasound shows a viable portion of nodular tissue (marked by vascularization) in the course of follow-up. Thus, it has been shown that nodules which according to these criteria require repeat ablation are those of larger size,21 and that in nodules with a volume > 20 ml, the number of sessions received influences the final volume reached.30 Compared with other studies involving single-session RFA and nodules with a mean initial volume > 20 ml, the decrease in volume obtained in our series was similar to that found in the literature,19,24,31 yet smaller than the reduction reported by other authors for nodules of initial volume < 20 ml.20 In three of the four hyperthyroid patients, treatment with methimazole could be discontinued, in concordance with the descriptions referring to both toxic adenomas and multinodular goiters, where RFA allowed for dose reduction or the discontinuation of antithyroid medication.21,32

The complications of RFA were generally mild and transient, and mostly consisted of local discomfort after the procedure, which subsided with conventional analgesia. The higher percentage of patients reporting mild pain (37.5%) as compared to other series after RFA is possibly related to the definition of the complications, since any pain leading to analgesic treatment after RFA was included as a complication. In those studies that considered the complications of RFA,13 mild transient pain was not regarded as a complication of RFA, and only pain lasting more than three days after the procedure was taken to be a minor complication in 2.6% of the cases. Low complication rates are usually recorded (<4%), including particularly mild spontaneously reabsorbing hematomas.13 Major complications are exceptional and involve problems such as transient dysphonia (1.4%) or nodule rupture (0.2%) with spontaneous recovery, as occurred in one of our patients. Nodule rupture is a consequence of sudden volume expansion within the nodule due to intranodular bleeding. The treatment in such cases is usually conservative, with analgesia and/or antibiotics in patients with associated signs of infection.

As with other hospitals,33 the protocol used at our center involves the conscious sedation of patients in order to avoid the discomfort generated during ablation. However, as expertise with the technique increases, ablation may be performed under local anesthesia alone, as occurs in the more experienced centers,21,31 in line with the recommendations of some guides.14

The limitations of our study include the small number of patients enrolled and a short follow-up period. Nevertheless, other studies suggest the persistence of RFA efficacy over the long term21 and up to at least four years after ablation.22 In future, increased experience, a better selection of RFA candidates, the inclusion of smaller nodules, and the possibility of a new ablation session in cases of larger nodules with evidence of viable tissue during follow-up could result in improved outcomes.

ConclusionsIn our study, with a limited number of patients, and in agreement with the findings of larger series, RFA was found to be effective and safe. Since RFA is an outpatient procedure that requires no skin incisions or general anesthesia, it would appear to be a useful alternative to surgery in cases where surgery is rejected or considered to pose a high risk to the patient.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Thanks are due to the help received from Laboratorios Menarini.

Please cite this article as: Familiar Casado C, Merino Menendez S, Ganado Diaz T, Pallarés Gasulla R, Pazos Guerra M, Marcuello Foncillas C, et al. Resultados de una sesión única de ablación por radiofrecuencia en nódulos tiroideos benignos: Resultados a 6 meses en 24 pacientes. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2020;67:164–171.