Prevalence of disease-related malnutrition in hospitals ranges from 20% to 50%. Use of nutritional screening tools should be the first step in the prevention and treatment of patients at risk of malnutrition and/or undernourished.

AimsTo implement a nutritional screening tool at admission to a tertiary hospital.

MethodsThe nutrition unit prepared a protocol for early detection of nutritional risk and selected the NRS 2002 as screening tool. The protocol was approved by the hospital committee of protocols and procedures and disseminated through the intranet.

NRS 2002 was included in the diet prescription software to be implemented by the nursing staff of the hospital wards and as a direct communication system with the nutrition unit. Three phases were designed: pilot phase, implementation phase, and consolidation phase.

ResultsThe pilot phase, NRS 2002 was implemented in 2 hospital units to monitor software. The implementation phase was carried out in the same units, and all action protocols related to it were verified. The consolidation phase consisted of sequential extension of the protocol to the other hospital units.

ConclusionsImplementation of nutritional screening at hospital admission is a long and complex process that requires involvement of many stakeholders. Computer software has allowed for a rapid, simple, and automatic process, so that the results of the screening are immediately available to the nursing staff of the nutrition unit and activate the nutritional protocols when required.

La prevalencia de la desnutrición relacionada con la enfermedad en el hospital varía del 20 al 50%. La utilización de herramientas de cribado debe ser el primer paso en la prevención y el tratamiento de los pacientes en riesgo de desnutrición o desnutridos.

ObjetivosImplantar un método de cribado nutricional al ingreso en el ámbito de un hospital terciario.

MétodosLa Unidad de Nutrición elaboró un protocolo de detección precoz del riesgo nutricional y eligió el NRS 2002 como herramienta de cribado. El protocolo fue aprobado por la Comisión de Protocolos y Procedimientos del hospital y difundido en la intranet.

El NRS 2002 se incluyó en el programa de prescripción de dietas para su realización por parte del personal de enfermería de las unidades de hospitalización y como sistema de comunicación directo con la Unidad de Nutrición. Se diseñaron 3 fases para la implantación: fase de pilotaje, fase de implantación y fase de consolidación.

ResultadosEn la fase de pilotaje se implantó el NRS 2002 en 2 unidades de hospitalización para monitorizar el software. La fase de implantación se realizó en las mismas unidades y se verificaron todos los protocolos de actuación relacionados con el mismo. La fase de consolidación consistió en ir ampliando sucesivamente las unidades de hospitalización con el protocolo implantado.

ConclusionesLa implantación de un cribado nutricional al ingreso hospitalario es un proceso largo y complejo, con la implicación de muchos estamentos. El programa informático ha posibilitado que la realización del mismo sea rápido, sencillo y automatizado, y que el resultado del cribado llegue inmediatamente al personal de enfermería de la unidad de Nutrición y se activen los protocolos de actuación de la misma.

The prevalence of disease-related malnutrition in hospitals ranges from 20 to 50%.1–4 The use of screening tools should be the first step in its prevention and in the treatment of patients with or at risk of malnutrition.5,6

Malnutrition is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, and thus logically increases healthcare costs.7–9

The European multicenter EuroOOPS study,10 which used the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002) tool to assess nutritional risk in 5061 hospitalized patients, found the risk of malnutrition to be 32.6%.

The PREDYCES study® (Prevalence of Hospital Malnutrition and Associated Costs in Spain),11 conducted by the Spanish Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (Sociedad Española de Nutrición Parenteral y Enteral [SENPE]), also provided very relevant data. The study was carried out in 1597 patients from 31 hospital centers, representative of the healthcare setting of the whole country and under conditions of standard clinical practice. The main results obtained are described below.

Twenty-three percent of the patients admitted to a Spanish hospital were at risk of malnutrition (according to the NRS 2002 screening test criteria). Patients over 70 years of age had a significantly greater nutritional risk than other patients (37% versus 12.3%). Both upon admission and at discharge, the highest prevalences of malnutrition corresponded to patients over 85 years of age (47% malnutrition upon admission and 50% at discharge).

On the other hand, 9.6% of the non-malnourished patients developed malnutrition during their hospital stay, while 28.2% of the patients admitted to hospital with nutritional risk showed no malnutrition at discharge.

Patients with malnutrition had a significantly longer hospital stay on average.

In economic terms, the hospital costs were higher in patients at nutritional risk, the difference being more marked among those who became malnourished during their hospital stay.

It therefore appears essential to routinely screen patients for nutritional risk at the time of their hospital admission.

Nutritional screening aims to detect patients who are at nutritional risk or who are already malnourished. It should be performed in all patients, regardless of their setting (outpatient, nursing home, hospital, etc.).

The premises for implementing a screening method are a significant prevalence of the condition to be ruled out, the possibility of starting early treatment, and the existence of an effective tool developed for this purpose. All of these criteria are met in the case of malnutrition.12

Screening methods also should be valid, reliable, reproducible and practical, and should be associated with specific action protocols.13

Due to the high prevalence of malnutrition at hospital admission, as well as of malnutrition occurring during the hospital stay, the previous recommendations developed in other settings suggest that screening should be performed upon the patient's admission to hospital by the nursing staff.14

Clinical, automated and mixed screening methods have been developed.15,16 Clinical screening methods include subjective and objective data (body weight, height, changes in weight, changes in intake, comorbidities, etc.). Automated screening methods in turn are based on analytical data but also compile other useful objective information (diagnosis, age, duration and evolution of the process, applied resources, etc.), available in the hospital operating system databases. As its name indicates, mixed screening comprises both types of information.

Of the multiple screening methods available for adult patients, the most commonly used are the Mini-Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA SF),17 the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST),18 the Nutrition Risk Screening (NRS 2002),19 the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA)20 and Nutritional Control (CONUT).21

The detection of a patient with or at risk of malnutrition using a screening tool requires the assessment of the patient's nutritional status. It has been suggested that this more specific, thorough and detailed assessment should be performed by specialized staff, who in turn will implement an adequate nutrition plan. If the application of screening methods shows that the individual is not at risk, reassessment should be made (at one week or 6 months, depending on whether the patient is hospitalized or not, or earlier in the event of clinical or management changes).11,22

The use of screening tools for an initial assessment allows for the early detection of malnourished patients or patients at risk of malnutrition, and facilitates their subsequent referral to more specific nutritional assessment and the start of appropriate nutritional treatment if necessary.

Considering the characteristics of our center and of the Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics Unit (Unidad de Nutrición Clínica y Dietética [UNCyD]), the decision was made to choose the NRS 2002 as the nutritional screening tool.

The present study describes the systematic approach used to implement the NRS 2002 nutritional screening tool upon patient admission in order to prevent malnutrition in adult patients admitted to our hospital.

Material and methodsThe NRS 2002 nutritional screening toolThe NRS 2002 was developed by the ESPEN ad hoc Danish working group.19 The first part uses four questions to analyze the body mass index (BMI), lowered intake during the previous week, weight loss, and the severity of the patient's disease. In the event of an affirmative answer, the second part of the screening tool is applied, yielding a score (0–3 points) according to weight loss, dietary intake and the BMI, and another score (0–3 points) according to the severity of the disease. Furthermore, one point is added if the patient is over 70 years of age. The final score may range from 0 to 7 points. When a score of ≥3 is obtained, the patient is classified as being “at nutritional risk”, and a nutritional management and monitoring plan should be established. This screening method is easy to use in hospitalized patients and presents high sensitivity, low specificity and a reliability or reproducibility index (k) of 0.67.23 There is even a recent study that validates the NRS 2002 in hospitalized patients with a k index of 0.956.24

Early nutritional risk detection protocolThe UNCyD developed an early nutritional risk detection protocol based on nutritional screening upon admission that was approved by the Protocols, Procedures and Clinical Practices Committee of the hospital on 24 April 2013. This protocol is accessible through the hospital intranet. It establishes the following:

- 1.

A complete nutritional screening (NRS 2002) is conducted within the first 48h by the nursing staff of the adult patients hospitalization unit.

- 2.

The screening result is recorded in the nursing history.

- 3.

If the screening proves negative, the patient is reassessed one week after admission, following the above guidelines.

- 4.

If the screening proves positive, the nursing staff of the hospital unit:

- a.

Reports the result to the physician responsible for the patient.

- b.

Informs the UNCyD nursing staff.

- a.

- 5.

The UNCyD nursing staff conducts a nutritional assessment.

- 6.

The action protocols in effect in the UNCyD are then activated.

A meeting was held in September 2013 among various professionals belonging to the Nutrition Unit, the Nursing Subdirectorate and the Information Systems Subdirectorate, in order to organize the nutritional screening software support. Because of the size of the hospital (1200 beds) and its distribution into several wards, the decision was made to include screening in the oral diet prescription program (Dietools® Dominion Digital, 1999, Spain), which is used in the hospital units by the nurses in charge of each patient, and constitutes a direct line of communication with the UNCyD staff.

Following this meeting, the company responsible for the diet program software designed and programmed specific software for the intended purpose.

In December 2013, the necessary software support for nutritional screening was ready. The results of the nutritional screening are reflected in the electronic case history of the patients, in the section referring to tests performed, so that they can be consulted by other healthcare staff. A specific icon was added to the electronic case history to quickly check whether a given patient had undergone nutritional screening, along with a warning system in case the patient was at nutritional risk.

After screening in the wards, the communication circuit with the UNCyD staff comes into effect, as described below.

Each morning, UNCyD nurses access the diet program to print the list of patients at nutritional risk detected the day before. The nutrition nurse performs nutritional assessment of the patients and prescribes appropriate nutritional treatment and its follow-up. This action plan is recorded in the electronic case history of the patient. The nurse informs the UNCyD medical staff when he/she considers that they should evaluate the patient.

Incorporation of the protocol for the detection of patients at nutritional risk was planned in three phases: a first pilot phase, an implementation phase, and a consolidation phase. The pilot phase consisted of implementing the protocol in two hospital units in order to obtain software feedback and identify possible problems. During the implementation phase, all the related action protocols were applied in those same hospital units: communication with the UNCyD and management of the patients by the UNCyD staff. Lastly, the consolidation phase involved successive expansions of the implemented protocol to the other hospital units.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the variables was carried out. The data are expressed as percentage and mean±standard deviation (SD).

ResultsNutritional screening pilot phaseThe hospital units selected for the pilot initiative were a medical (Internal Medicine) and a surgical unit (Urology). Intensive training sessions were organized in all shifts for the nursing staff of these units in order to explain the importance of nutritional status in hospitalized patients and the need to detect those individuals at nutritional risk early upon admission.

To support the nursing staff of these units, the head of the Nursing Unit and a dietician of the Nutrition Unit supported the hospital staff during the two months duration (Monday to Friday, excluding public holidays) of the pilot project.

On 1 April 2014 the pilot phase began in both units. A total of 14 nurses from the Departments of Urology and Internal Medicine participated in the initiative. During the first two weeks of the pilot phase, we recorded the total number of assessments made in each unit and by each nurse, the time used to complete the assessment, and whether only the first part of the screening or a full screening was performed. The results are detailed below.

A total of 67 assessments were performed, of which:

- –

only the first part of the screening was performed: 53 assessments.

- –

both the first part and the second part were performed (full screening): 14 assessments.

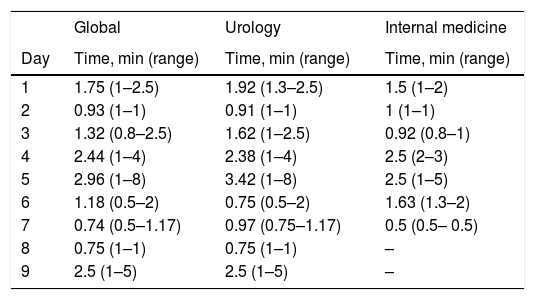

Each nurse performed a daily minimum and a maximum of: 1–4 nutritional screenings. Table 1 shows the mean assessment times and range (min–max) for each day.

Time dedicated to nutritional screening.

| Global | Urology | Internal medicine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Time, min (range) | Time, min (range) | Time, min (range) |

| 1 | 1.75 (1–2.5) | 1.92 (1.3–2.5) | 1.5 (1–2) |

| 2 | 0.93 (1–1) | 0.91 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) |

| 3 | 1.32 (0.8–2.5) | 1.62 (1–2.5) | 0.92 (0.8–1) |

| 4 | 2.44 (1–4) | 2.38 (1–4) | 2.5 (2–3) |

| 5 | 2.96 (1–8) | 3.42 (1–8) | 2.5 (1–5) |

| 6 | 1.18 (0.5–2) | 0.75 (0.5–2) | 1.63 (1.3–2) |

| 7 | 0.74 (0.5–1.17) | 0.97 (0.75–1.17) | 0.5 (0.5– 0.5) |

| 8 | 0.75 (1–1) | 0.75 (1–1) | – |

| 9 | 2.5 (1–5) | 2.5 (1–5) | – |

After this period, the nurses highlighted those sections or questions that proved very complex or involved some difficulty. No item was seen to be very complex, and in only 5 cases was some section described as involving difficulty.

The difficulties encountered and the suggestions made by the nurses concerned the following:

- 1.

The patient may be alone, cannot be weighed, and is unable to answer the questions.

- 2.

Too much time is spent on weighing the patient.

- 3.

Too much time is spent on asking questions regarding intake.

- 4.

The program should file the patient's weight of the previous week, to avoid it having to be re-entered for reassessment.

- 5.

Some type of software warning system should be installed to indicate when a given patient has been screened.

- 6.

Some type of software warning system should be installed for those patients requiring reassessment because they have been admitted for one week or longer.

During the following weeks, only the following variables were checked, and the times were not monitored:

- –

the number of patients admitted in the previous 24h.

- –

the number of admitted patients screened.

- –

the number of reassessments to be performed.

- –

the number of reassessments performed.

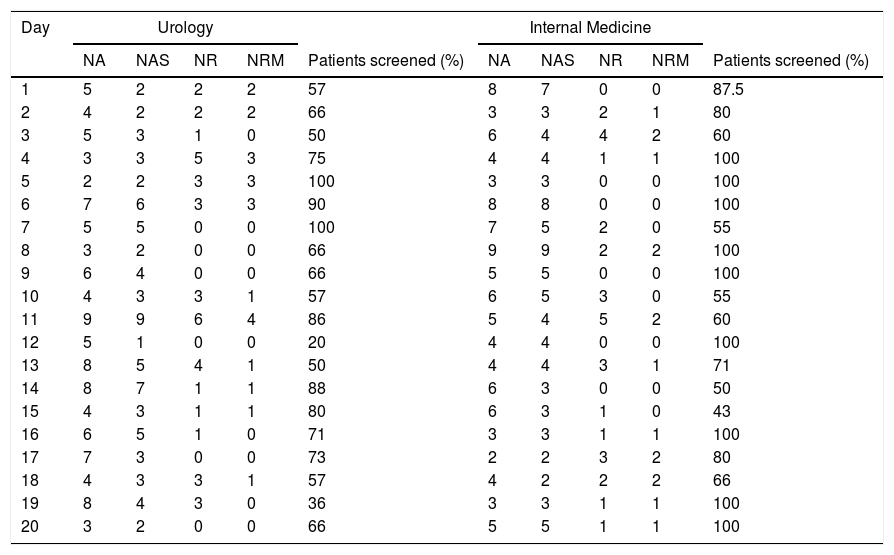

The results are shown in Table 2.

Number of patients screened.

| Day | Urology | Internal Medicine | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA | NAS | NR | NRM | Patients screened (%) | NA | NAS | NR | NRM | Patients screened (%) | |

| 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 57 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 87.5 |

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 66 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 80 |

| 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 50 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 60 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 75 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 6 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 90 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 7 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 55 |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 66 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 9 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 66 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 10 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 57 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 55 |

| 11 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 86 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 60 |

| 12 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 13 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 50 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 71 |

| 14 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 88 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| 15 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 80 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 43 |

| 16 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 71 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 17 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 73 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 80 |

| 18 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 57 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 66 |

| 19 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 36 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 20 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 66 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

NA, number of patients admitted in the previous 24h; NAS, number of admitted patients screened; NR, number of reassessments to be performed; NRM, number of reassessments made.

During this pilot phase, the nutritional screening rate was 67.7±20.3% in Urology and 80.3±19.7% in Internal Medicine.

Nutritional screening implementation phaseThis second phase lasted 6 months, from June to November 2014.

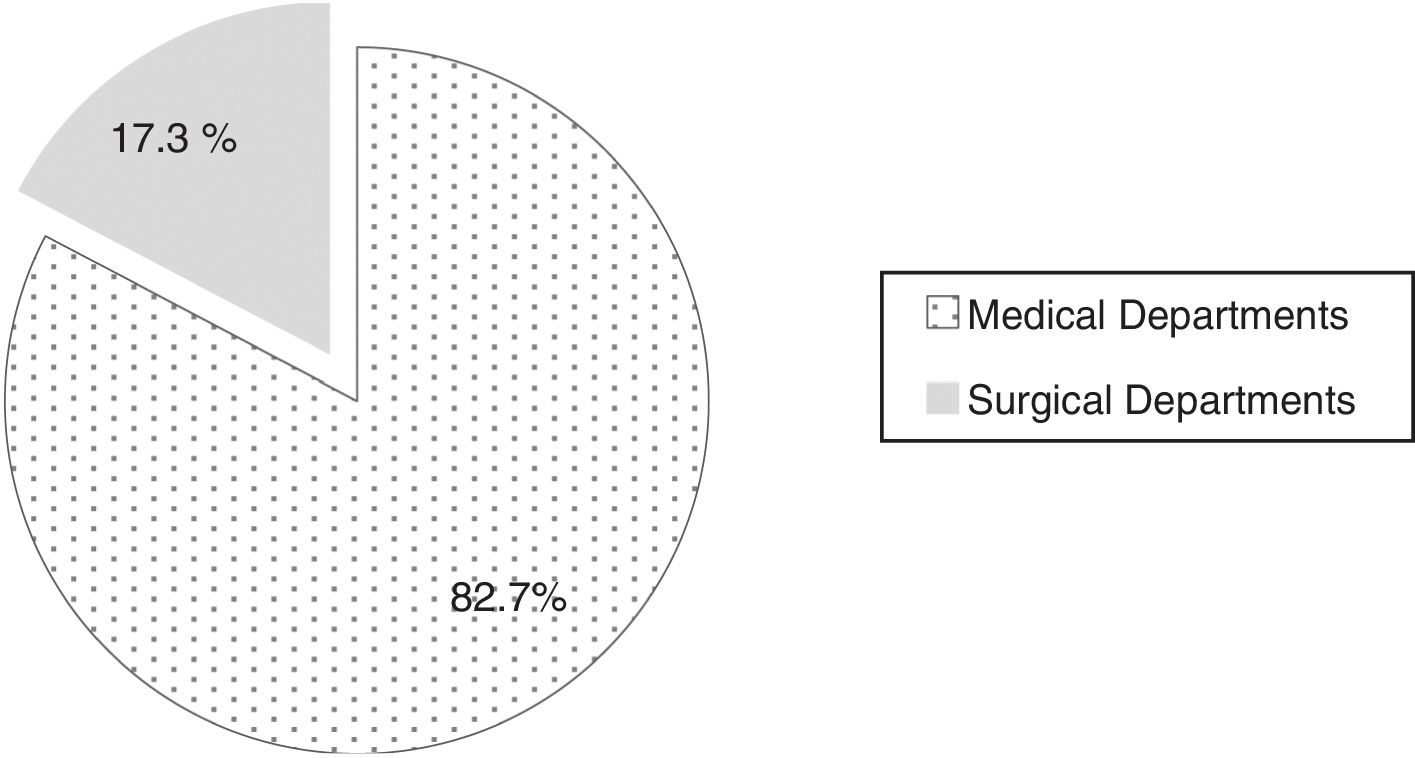

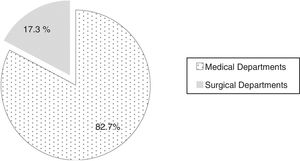

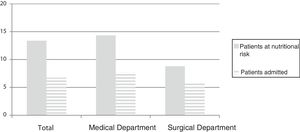

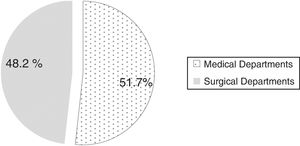

In this phase, nutritional screening was performed in 1123 of the 1521 patients admitted to these hospital units (Urology and Internal Medicine), which represents 73% of the total patients screened in these units during hospital admission. Of these, 209 patients had a positive nutritional screening result, representing a 19% incidence of patients at nutritional risk. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the patients at nutritional risk according to the Department to which they were admitted.

Of the patients with a positive screening result, 87% were detected at the screening performed within the first 24–48h of admission.

The NRS 2002 covers three key aspects: alterations in nutritional status, disease severity, and age>70 years. We sought to determine which aspect was most affected in the patients at nutritional risk at our hospital. Seventy-seven percent of the patients at nutritional risk were over 70 years of age, 33% had a higher altered nutritional status score, and 27% had a higher disease severity score. The remaining 40% yielded the same score for both of the aforementioned aspects.

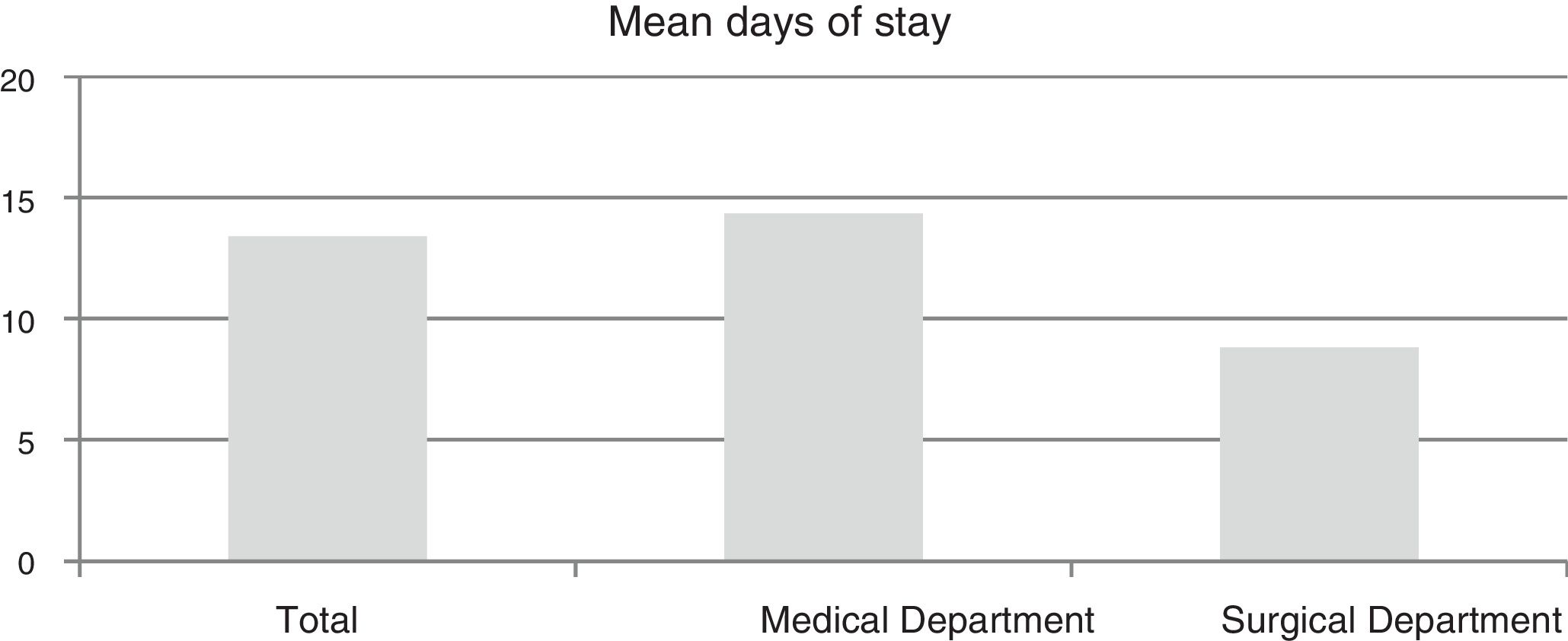

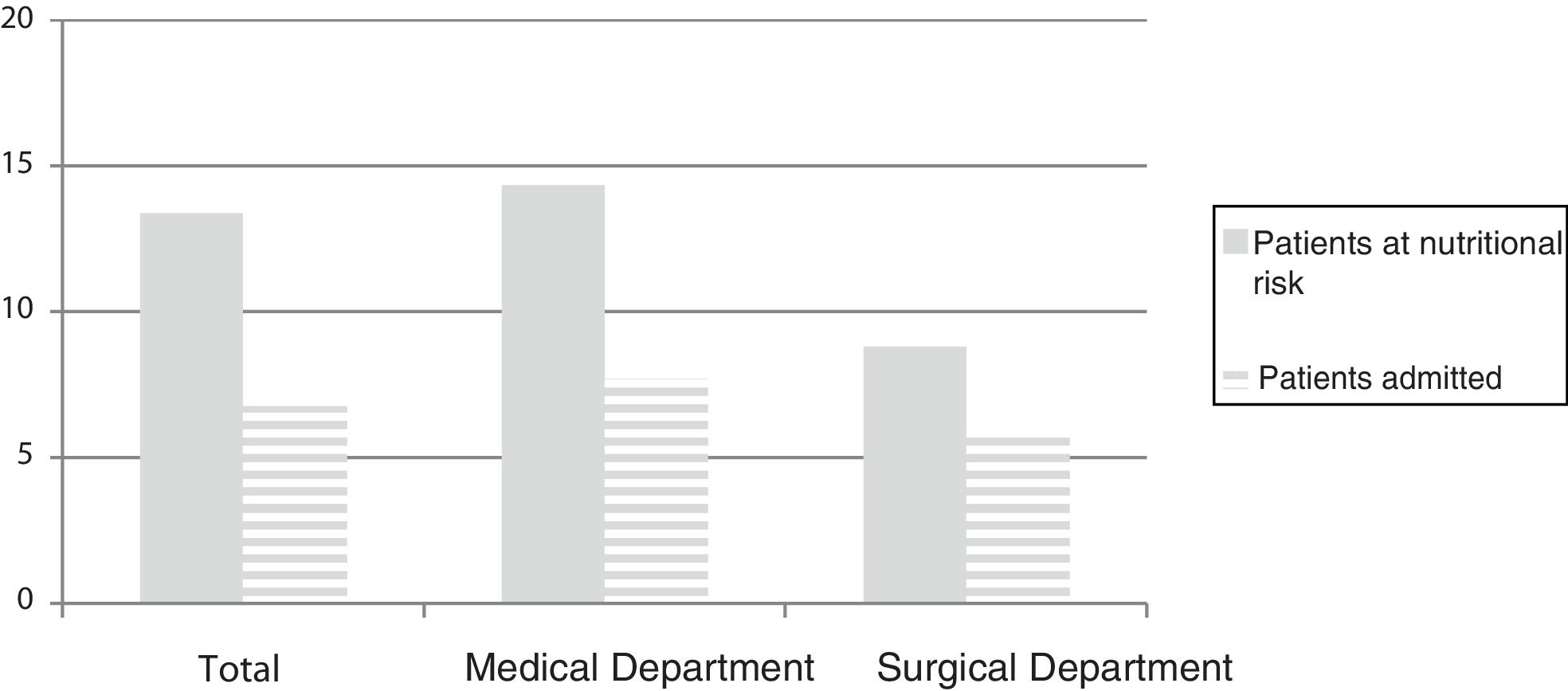

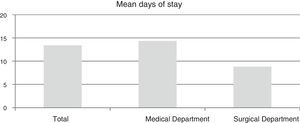

Fig. 2 shows the mean duration of stay of the patients at nutritional risk.

We sought to compare the mean stay of the patients at nutritional risk versus the mean stay of the patients admitted to the above-mentioned hospital units. The mean stay corresponding to each hospital unit was obtained from the patient management program of the hospital, and included all the admitted patients, both those at nutritional risk and those not at risk. We acknowledge this as a limitation in establishing the comparison (Fig. 3).

An analysis was made of the 30-day readmission rate and the mortality rate of the patients at nutritional risk. Twenty-five percent of the patients at nutritional risk were readmitted in under 30 days, and the mortality rate was 5%.

Nutritional screening consolidation phaseThe nutritional screening consolidation phase was carried out gradually in all the adult hospital units, from 1 January to 17 June 2015.

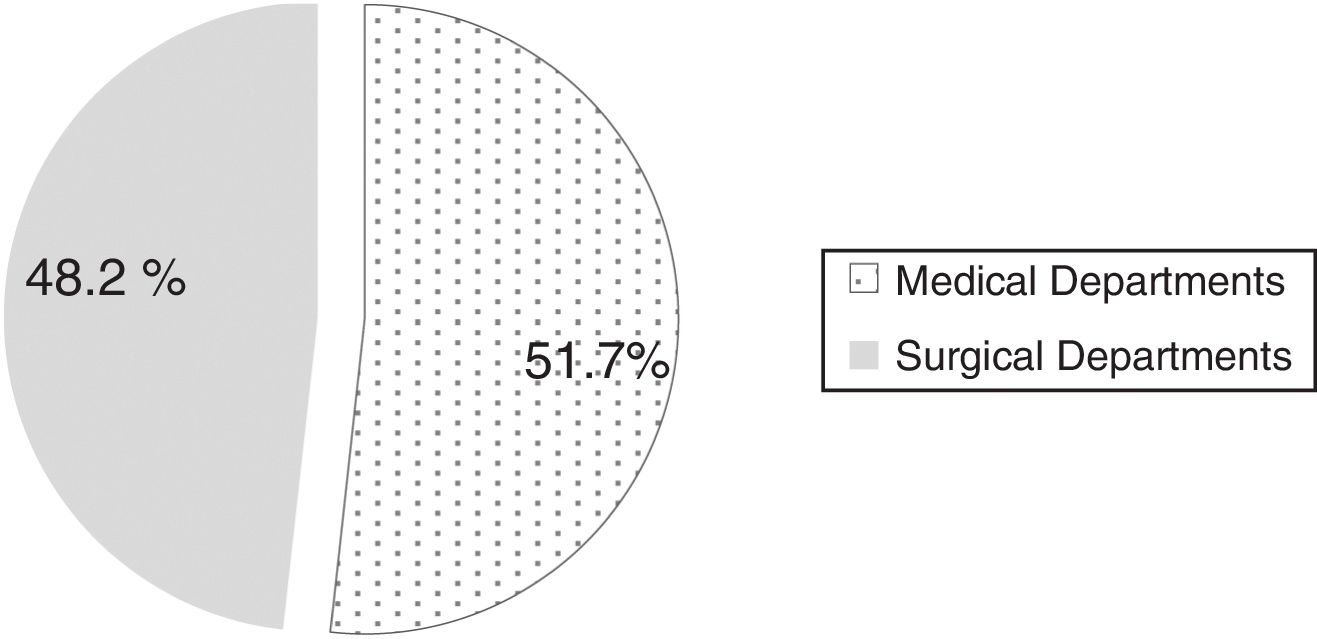

A total of 2527 patients were screened during this period. Of these, 373 had a positive nutritional screening result (NRS 2002≥3 points), representing 15% of the patients at nutritional risk, and 73% of them were over 70 years of age.

Fig. 4 describes the distribution of patients at nutritional risk.

From the consolidation of the project in June 2015 until May 2017, nutritional screening was performed in 38,313 patients, and the percentage of patients at nutritional risk was found to be 20%.

DiscussionThe implementation of nutritional screening at hospital admission allows for early action targeted at those patients at nutritional risk.

Considering the infrastructure of our Nutrition Unit and the characteristics and logistics of the center, we felt the NRS 2002 to be the most appropriate screening tool for implementation at our hospital. The incorporation of screening was a long and complex process, but after many months of work at all the levels involved, it can now be applied rapidly by the nursing staff, given that the software allows for easy and automated processing. No increase in nursing staff has been required for implementing the protocol. Likewise, it has been possible for screening (regardless of its result) to immediately reach the nursing staff of the Unit, allowing them to act accordingly, either solving the problem themselves or notifying the physicians of the Unit.

It should also be noted that all hospital professionals can access the screening result through the electronic case history, in the same way as with any other patient test.

In any case, and as commented on in the Introduction, the problem of malnutrition related to disease is of such magnitude that it is essential for all hospitals to have protocols including nutritional screening upon patient admission. However, the choice of method should be conditioned to the characteristics of the center and to the available resources.25,26

Nevertheless, there are a number of features which all adequate screening protocols should have. A screening protocol must have content validity and predictive validity, reliability or reproducibility, and must be practical (easy to apply, well accepted, inexpensive). In addition, it must be possible to incorporate it to specific action protocols.

In this regard, the NRS 2002 predicts mean stay, infectious and non-infectious complications, patient destination at discharge, and mortality.10,27

The morbidity-mortality and hospital stay data we obtained in patients at nutritional risk are similar to those found in the literature.28–30 In the implementation phase, the patients at nutritional risk in the surgical department were fewer than in other published series; however, it should be noted that these were patients admitted to the Department of Urology, mostly for elective surgery and with a good prior nutritional status.

These characteristics also apply in other screening methods, both clinical (MUST, MNA, NRI, SGA, etc.) and automated (CONUT, FILNUT, etc.) or mixed screenings. We therefore stress that while screening should be mandatory, the tool used is optional.

In addition to the abovementioned characteristics referring to screening tools, a clear and precise action protocol should be adopted when screening is started at the hospital.

In this regard, in 2011 the SENPE31 established a multidisciplinary consensus on the approach to hospital malnutrition in Spain. This document emphasizes a number of guidelines to be followed. For example, the contemplated screening protocol should always be performed in the first 24–48h after hospital admission (grade of recommendation A). Screening should be performed by trained healthcare professionals with experience of being in charge of patient care (grade of recommendation D). In the event of a positive screening result, adequate procedures should be established which allow for a complete assessment of the nutritional status of the patient and for the adoption of the necessary nutritional therapeutic measures (diet optimization, oral nutritional supplements, enteral nutrition, etc.) (grade of recommendation D).

The document also emphasizes that patients with negative nutritional screening findings upon admission should be reassessed after at least one week (grade of recommendation D).

As emphasized throughout our study, the implementation of nutritional screening in a hospital is a long and complicated process, and one not without setbacks and difficulties, though the effort is well worth it. Based on our experience, we believe that in order for a project of this magnitude to be implemented successfully, contributions are required at many levels (from hospital management, nursing departments, information technology, etc.), without forgetting the need for ongoing training of all the staff involved. Such training must be repeated regularly, because changes in staff are very common (particularly in nursing), and information and training must be implemented if nutritional screening at admission is to become part of standard practice among the healthcare professionals involved.

The incorporation of nutritional screening also should be considered an incentive, an area for improvement that needs to be implemented in our patients.

AuthorshipPGP designed the protocol, drafted the manuscript and approved the final version.

CVG designed the protocol, participated in drafting and reviewing the manuscript, and approved the final version.

LFG designed the protocol, conducted the pilot phase, and approved the final version.

IHG conducted the pilot phase and approved the final version.

IBL designed the protocol and approved the final version.

MCA designed the protocol and approved the final version.

CCC designed the protocol, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The implementation of an early malnutrition detection and follow-up program upon admission of adult patients to our center (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain) was possible thanks to the support of the hospital management at its various levels (General, Medical, Nursing), Information Technology, and the Department of Preventive Medicine and Quality.

Likewise, thanks are due to all the UNCyD staff for their crucial contribution and enthusiasm for this project.

Please cite this article as: García-Peris P, Velasco Gimeno C, Frías Soriano L, Higuera Pulgar I, Bretón Lesmes I, Camblor Álvarez M, et al. Protocolo de implantación de un cribado para la detección precoz del riesgo nutricional en un hospital universitario. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:555–562.