Gestational diabetes (GD) is related to development of diabetes mellitus (DM) after delivery. The predictive factors in this association are not yet well defined. Objective: to study the predictive factors of dysglucosis in the postpartum period in a sample of patients with GD.

Material and methodsA total of 1765 women with DG were studied. Variables analyzed: anthropometric data and maternal history. Glycemia in OGTT with 100g (basal: 1, 2 and 3h) and HbA1c. Use of insulin in pregnancy. The OGTT with 75g and HbA1c at 3 months after delivery.

ResultsPostpartum DM prevalence 2.1%. Among these patients, there was a higher percentage of patients with a history of GD (25.9 vs. 12.9%; p<0.05), pre-pregnancy obesity (20.8 vs. 14.9%; p<0.05) and insulin use during pregnancy (79.2 vs. 20%; p<0.01). In the OGTT with 100g, the number of pathological points was higher (3.18±0.69 in DM vs. 2.3±0.28 normal, 2.6±0.47 IFG, 2.5±0.32 IGT; p<0.001). In the OGTT 100g, the blood glucose level above which the diagnosis of postpartum DM is most likely is 189mg/dl in the 2h determination (S: 86.2%, E: 72%). A level of HbA1c≥5.9% during pregnancy has a specificity of 95.9% for the diagnosis of postpartum DM in our sample.

ConclusionWe show factors associated with the diagnosis of postpartum DM, among which are quantitative determinations such as glycemia at 2h of the OGTT with 100g and HbA1c during pregnancy in patients with DG.

La diabetes gestacional (DG) está relacionada con el desarrollo de la diabetes mellitus (DM) tras el parto. Los predictores en esta asociación aún no están bien definidos. El objetivo de nuestro trabajo es estudiar los factores predictores de disglucosis en el posparto en una muestra de pacientes con DG.

Material y métodosUn total de 1.765 mujeres con DG fueron estudiadas. Variables analizadas: datos antropométricos y antecedentes maternos. Glucemia en sobrecarga de glucosa (SOG) con 100g (basal: 1, 2 y 3h) y HbA1c. Uso de insulina en la gestación. La SOG con 75g y HbA1c a los 3 meses tras el parto.

ResultadosPrevalencia DM posparto: 2,1%. Entre estas pacientes hubo mayor porcentaje de pacientes con antecedentes de DG (25,9 vs. 12,9%; p<0,05), obesidad pregestacional (20,8 vs. 14,9%; p<0,05) y uso de insulina durante el embarazo (79,2 vs. 20%; p<0,01). En la SOG con 100g, el número de puntos patológicos fue mayor (3,18±0,69 en DM vs. 2,3±0,28 normal, 2,6±0,47 GBA, 2,5±0,32 IHC; p<0,001). En la SOG con 100g, el nivel de glucemia por encima del cual es más probable el diagnístico de DM posparto es 189mg/dl en la determinación a las 2h (S: 86,2%; E: 72%). Un nivel de HbA1c≥5,9% durante la gestación tiene una especificidad del 95,9% para el diagnóstico de DM posparto en nuestra muestra.

ConclusiónEvidenciamos factores asociados al diagnóstico de DM posparto entre los que se encuentran determinaciones cuantitativas como la glucemia a las 2h de la SOG con 100g y la HbA1c durante la gestación en pacientes con DG.

Gestational diabetes (GD) is defined as carbohydrate intolerance of variable intensity diagnosed for the first time during pregnancy, regardless of the treatment used to control it or its postpartum course.1

The prevalence of GD in Spain ranges from 4.5% to 11.6% of all pregnancies, depending on the study and the criteria used to diagnose the condition.2

Gestational diabetes is related to metabolic syndrome, high blood pressure, dyslipidemia and obesity in the future, and the literature indicates that over 50% of all affected patients develop type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) in the course of follow-up.3 The current clinical practice guidelines4 therefore recommend early patient reassessment after delivery. However, in routine practice it is difficult to ensure patient compliance once pregnancy has ended.5

There is evidence that the incidence of DM can be reduced by the adoption of healthy lifestyle habits. Despite this, some studies have found that less than half of all patients with GD undergo postpartum reassessment.6

The reporting of factors implicated in the development of DM may help increase the number of patients adhering to prevention programs.

However, the lack of data for individual risk estimation means that the healthcare professionals involved in the care of women with GD fail to optimize patient counseling in this regard.7

We therefore conducted a study with the primary aim of analyzing the factors related to postpartum diabetes in a sample of patients with GD.

Material and methodsA retrospective observational study was made, using information collected from the specialist GD unit of Hospital Universitario de Getafe (Madrid, Spain). We selected a total of 1765 single pregnancy women diagnosed with GD according to the criteria of the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) between 1993 and 2013. The study was carried out with the approval of the hospital Ethics Committee.

We evaluated the women with no history of diabetes between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy based on the O'Sullivan test after a 12-h fasting period. If any known risk factor for GD was detected (age>35 years, a body mass index [BMI]≥30kg/m2, previous GD or a family history of DM), the screening test was performed in the first trimester of pregnancy. When the plasma glucose levels recorded 1h after an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with 50g were ≥140mg/dl, the OGTT was repeated with 100g, and the fasting plasma glucose levels were measured 1, 2 and 3h after intake, with the recording of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (DCCT). Gestational diabetes was diagnosed according to the NDDG criteria: two or more plasma glucose values above the following limits: 105mg/dl basal: 190mg/dl in 1h, 165mg/dl in 2h and 145mg/dl in 3h.

If GD was diagnosed, we prescribed dietary measures (50% carbohydrate, 20% protein and 30% fat) with a calorie supply of 35kcal/kg in low-weight patients, 30kcal/kg in patients with normal weight, 25kcal/kg in overweight women and 15kcal/kg in obese patients. In addition, recommendations for moderate and regular physical activity (brisk walking for at least 1h a day) were made. Insulin therapy was started if optimal glycemia targets were consistently not met (fasting capillary blood glucose>95mg/dl or 1h postprandial>140mg/dl).

Three months after delivery, an OGTT was performed with 75g and HbA1c (DCCT) was measured in order to reassess postpartum altered glucose. Normal fasting glycemia was defined as <100mg/dl and 2h <140mg/dl; impaired fasting glucose (IFG) was defined as fasting glycemia between 100 and 125mg/dl; carbohydrate intolerance (CHI) was defined as blood glucose after 2h between 140 and 199mg/dl; and DM was defined as fasting glycemia≥126mg/dl and/or 2h ≥200mg/dl.

The exclusion criteria were multiple pregnancies, delivery <20 weeks and incomplete follow-up to delivery.

The following data were analyzed.

Clinical dataMaternal age, maternal origin and maternal pregestational body weight (kg) and the BMI (kg/m2), obesity being defined as a BMI≥30kg/m2, together with weight gain during pregnancy, a history of DM in first-degree relatives, and a history of GD in the patient.

Laboratory test dataPlasma glucose in GD diagnostic testing after an OGTT with 100g (basal: 1, 2 and 3h). The number of points with pathological blood glucose values among the four measurements (2, 3 or 4 pathological points in the OGTT). The glycemic response to reassessment testing three months after delivery using an OGTT with 75g. Glycosylated hemoglobin at the time of the diagnosis of GD and three months after delivery. Insulin use during pregnancy in order to secure good blood glucose control.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were reported as frequency distributions, and quantitative variables as the mean and standard deviation (SD) (data exhibiting a normal distribution).

The behavior of the quantitative parameters was analyzed for each of the independent variables based on the Student t-test (for comparisons of a variable with two categories) or analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Diagnostic performance curves (receiver operating curves [ROCs]) were used for the parameters of the OGTT with 100g in order to detect the points discriminating the presence of postpartum DM, with the calculation of sensitivity and specificity.

Linear regression models were fitted to assess factors associated with the development of postpartum DM.

Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05. The SPSS® version 15.0 statistical package for MS Windows® was used throughout.

ResultsA total of 1765 patients were included in the study, with an age of 32.5±4.3 years (mean±SD). Of these patients, 14.2% (n=251) were foreigners. The pregestational BMI was 26.9±5.4kg/m2, and 21.6% of the patients had pregestational obesity. A total of 60.6% of the sample had a history of first-degree relatives with DM, and 13.1% had experienced at least one episode of GD in previous pregnancies.

The diagnosis of GD leading to the start of treatment (based on dietary and physical activity recommendations) was established at 29.2±5.9 weeks of pregnancy on average. During pregnancy, insulin therapy was required by 20.1% of the patients to improve blood glucose control (Table 1).

Maternal characteristics of the study sample: personal history, family history, anthropometric measurements and percentage of patients treated with insulin.

| Mean age (years) | 32.5±4.3 |

| Family history of DM (%) (n=1070) | 60.6 |

| History of GD (%) (n=231) | 13.1 |

| Mean pregestational weight (kg) | 68.4±14.7 |

| Mean height (m) | 1.59±0.06 |

| Pregestational BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9±5.4 |

| Obesity (%) (n=381) | 21.6 |

| GD diagnosis week | 29.2±5.9 |

| Insulin (%) (n=354) | 20.1 |

| Weight at start of third trimester (kg) | 75.6±14.1 |

| Total weight gain (kg) | 8.2±5.3 |

GD: gestational diabetes; DM: diabetes mellitus; BMI: body mass index.

With regard to the neonatal and delivery characteristics, 10.1% of the infants presented macrosomia (n=171). In turn, 27.1% of the deliveries were by cesarean section (n=474), and the mean gestational age at delivery was 38.8±2.1 weeks.

At an average of 3.5 months (±0.4) after delivery, the OGTT was performed with 75g of glucose to determine whether any postpartum glucose alterations persisted. This reassessment found that 77.8% of the women had a normal OGTT, 9.5% presented IFG, 10.8% had CHI, and 2.1% were diagnosed with DM after pregnancy. A total of 524 patients (29.7%) were lost over postpartum follow-up. Thus, a total of 1241 patients (70.3%) were followed-up on until reassessment after delivery. Analysis of the baseline characteristics of the patients lost to follow-up revealed no statistically significant differences versus the other patients.

In the analysis of predictors of DM after delivery, we took into consideration the clinical and laboratory test parameters, focusing mainly on blood glucose levels in the OGTT with 100g and HbA1c during pregnancy (DCCT).

Clinical dataThe study of the clinical parameters showed differences according to a history of GD in previous pregnancies. In this regard, 25% of the patients who finally had postpartum DM presented a history of GD in previous pregnancies, versus only 12.9% of the patients who did not have DM after delivery (p<0.05).

In the patients of other origin (i.e., not Spanish), the probability of postpartum DM was higher than among the Spanish patients (6.8% versus 1.3%; p<0.01).

Differences were also found in relation to pregestational obesity, with the percentage of DM in obese patients being 20.8% versus 14.9% in the non-obese women (p<0.05).

Statistically significant differences were observed in relation to insulin use: of the patients who finally had DM after delivery, 79.2% required insulin treatment to improve their blood glucose control, while only 20% of the women with no DM at reassessment required insulin treatment (p<0.01).

There were no significant differences in the postpartum reassessment results after the family history of DM was taken into consideration (59.2% versus 61.3% of the patients with postpartum DM) (p>0.05).

Likewise, no differences were found in maternal weight gain during pregnancy, with the patients with no DM after delivery presenting a weight gain of 8.1.±4.3kg versus 8.3±5.9kg in those with postpartum DM (p>0.05).

Laboratory test dataOn analyzing the laboratory test data, we focused on the OGTT glycemia measurements with 100g of glucose and the HbA1c levels during pregnancy.

Oral glucose tolerance test with 100gThe mean glycemia values recorded in the diagnostic OGTT with 100g were as follows: mean basal blood glucose: 91.6±16.0mg/dl; after 1h: 210.2±27.7mg/dl; after 2h: 187.4±27.7mg/dl; and after 3h: 138.4±37.0mg/dl.

In the above-mentioned OGTT with 100g of glucose, 15.5% of the global patients presented pathological glycemia at baseline, 82.6% showed impaired glycemia in the measurement obtained after 1h, 91.6% in the measurement after 2h, and 42.5% in the measurement after 3h.

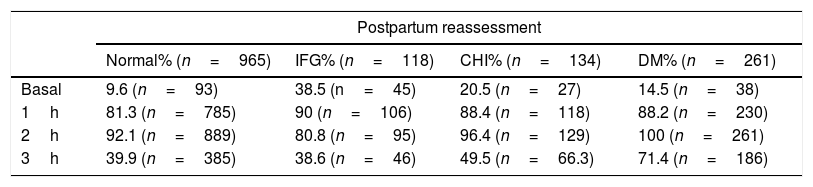

The percentage of patients with pathological findings at the different points of the OGTT with 100g of glucose according to postpartum reassessment is given in Table 2.

Percentage of patients with pathological blood glucose levels at the different OGTT 100g measurement points according to the postpartum reassessment groups (normal, IFG, CHI and DM).

| Postpartum reassessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal% (n=965) | IFG% (n=118) | CHI% (n=134) | DM% (n=261) | |

| Basal | 9.6 (n=93) | 38.5 (n=45) | 20.5 (n=27) | 14.5 (n=38) |

| 1h | 81.3 (n=785) | 90 (n=106) | 88.4 (n=118) | 88.2 (n=230) |

| 2h | 92.1 (n=889) | 80.8 (n=95) | 96.4 (n=129) | 100 (n=261) |

| 3h | 39.9 (n=385) | 38.6 (n=46) | 49.5 (n=66.3) | 71.4 (n=186) |

DM: diabetes mellitus; IFG: impaired fasting glucose; CHI: carbohydrate intolerance; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test.

Independently of postpartum reassessment, the blood glucose values most often found to be altered in the OGTT with 100g of glucose were those corresponding to one and 2h after glucose intake in all the groups (p<0.01). Statistically significant differences were observed on comparing the values 1 and 2h after glucose intake versus baseline and the 3h point (p<0.01). By contrast, no significant differences were recorded between the measurements after 1 and 2h (p>0.05) or at baseline versus the measurement after 3h (p>0.05) (Table 2).

In relation to the percentage of patients presenting alterations of the different points of the OGTT with 100g of glucose, the postpartum reassessment showed the group with IFG to include a larger proportion of women with pathological glucose values at baseline (p<0.001) (Table 2).

No statistically significant differences were found for the remaining measurement points.

Since the diagnosis of GD according to the NDDG is based on the recording of two or more pathological points in the OGTT with 100g, we studied the percentage of patients with 2, 3 or 4 pathological points (baseline: 1, 2 or 3h).

We found that 76% of the patients had two pathological points, 25.6% three points, and 2.4% four pathological points.

With regard to the number of pathological points according to the situation at postpartum reassessment, differences were found between patients who finally had DM after delivery (3.18±0.69) versus those without (2.5±0.45) (p<0.001). The fact of yielding pathological glycemia values at all four points of the OGTT was related to postpartum DM: 12% of these patients presented postpartum DM versus only 1.1% of those with two or three pathological points (p<0.01).

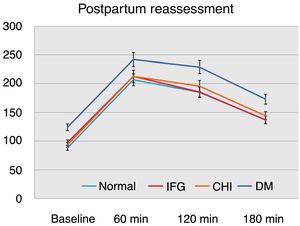

On considering the glycemia values in the OGTT with 100g of glucose according to postpartum reassessment, we found that the women with postpartum DM had significantly higher values at baseline and after 1, 2 and 3h versus the other groups (p<0.01) (Fig. 1).

We found no statistically significant differences on comparing the values of the OGTT with 100g of glucose among the groups with normal values at reassessment, IFG or CHI at postpartum (Fig. 1).

Taking the above into account, we analyzed the data based on the ROC curves for each of the points of the OGTT with 100g of glucose, and found the most representative point in relation to postpartum DM to be the measurement obtained 2h after glucose intake (p<0.01; with AUC: 0.85). Within this setting, the most sensitive and specific glycemia value for predicting postpartum DM was seen to be 189mg/dl (sensitivity: 86.2%; specificity: 72%) (Table 3).

Sensitivity, specificity and ROC curve corresponding to blood glucose at each OGTT 100g measurement point in patients with postpartum DM.

| OGTT 100g | Glycemia (mg/dl) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Area ROC curve | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | 97 | 72.3 | 74.1 | 0.76 | 0.65–0.89 |

| 1h | 222 | 73.4 | 74.5 | 0.72 | 0.52–0.84 |

| 2h | 189 | 86.2 | 72.0 | 0.85 | 0.72–0.92 |

| 3h | 150 | 72.9 | 60.2 | 0.72 | 0.52–0.85 |

DM: diabetes mellitus; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test.

The mean HbA1c concentration at the time of the diagnosis of GD was 5.3%±0.4, versus 5.2%±0.6 at postpartum reassessment.

On examining the HbA 1c levels during pregnancy and after delivery in relation to postpartum reassessment, we observed significant differences in HbA 1c on comparing the patients with DM after delivery versus the other groups (Table 4).

In relation to the above, we explored the possible existence of an association between HbA1c measured during pregnancy and the development of postpartum DM. We found an HbA1c concentration of 5.9% or higher to be very specific in predicting postpartum DM (specificity: 95.9%; sensitivity: 69%; area under the ROC curve: 0.77) (p=0.01).

The multivariate analysis adjusted for age, the maternal BMI, maternal origin and fasting glucose showed a statistically significant relationship between blood glucose measured 2h after the OGTT and a diagnosis of DM after delivery (p=0.02), and between HbA1c determined at the diagnosis of pregnancy and postpartum DM (p=0.03).

DiscussionThe risk of DM in patients with a history of GD is clearly high, with over 50% of such patients developing DM over the years.8,9

The incidence reported in the literature is highly variable, ranging from 3% at early postpartum assessment (3–6 months)10 to 50–70% at 15–25 years postpartum.3

For this reason, the clinical guidelines recommend assessment following delivery at intervals of approximately 4–12 weeks using the OGTT with 75g of glucose.4 However, in this phase a considerable percentage of patients are lost to follow-up, and the test is not performed. Studies of GD analyzing data based on postpartum reassessment usually assume a loss to follow-up of over 50%.10,11 In our study, we were able to follow-up on over 70% of the women in postpartum reassessment, so giving an added value to the results obtained.

The early identification of patients with a greater probability of postpartum DM is very important. In this regard, and based on objective data, we should insist on the need for a reassessment of blood glucose alterations after delivery, with the OGTT being given early when required.

A comprehensive review of the risk factors for DM in patients with GD shows clinical data such as pregestational overweight or obesity to be the most commonly analyzed factors,12–14 along with insulin use during pregnancy3,15 or a history of GD in previous pregnancies.16,17

A meta-analysis conducted in 2016 by Rayanagoudar et al.18 showed that women requiring insulin to improve the control of GD are at a greater risk of developing future DM, with a relative risk (RR) of 3.66 as compared to those not requiring insulin. In obese patients the RR was 3.18. There is strong evidence of an association between these factors and DM in women with a history of GD,19–21 which is consistent with the data obtained in our study.

In studies examining laboratory test data as predictors of DM after delivery, the most widely analyzed parameter is fasting blood glucose, which appears to be related to the development of future DM.10,22–24

However, fewer studies have analyzed the remaining measurement points in the OGTT with 100g of glucose. The meta-analysis conducted by Rayanagoudar et al.18 suggests that the blood glucose levels at baseline and recorded at 1, 2 and 3h in the OGTT with 100g may be related to the occurrence of postpartum DM (RR: 3.5, 3.05, 3.46 and 3.2, respectively), though the supporting studies are very few and the level of evidence is therefore very low.25

A number of studies have been carried out in the Spanish population, such as that published by Albareda et al.26 These authors identified the pregestational BMI, glycemia>210mg/dl at 2h and the presence of four pathological points in the OGTT as predictors of diabetes. Mention should also be made of a recent study carried out by Monroy et al.27 in which an association was recorded between glycemia at each OGTT measurement point and the risk of postpartum glycemia disorders (RR between 1.0 and 1.4).

In our study we focused on the data which could be afforded by the OGTT with 100g of glucose. We found a large proportion of the patients to be diagnosed with GD on the basis of only two altered points on the curve (76% of the women versus 25.6% with 3 altered points and 2.4% with 4 altered points). The most frequently altered measurements were those obtained one and 2h after glucose intake; these were therefore the two most relevant points in diagnosing GD.

In patients with postpartum DM, the blood glucose levels in the above-mentioned OGTT were higher. We thus sought to determine the most significant measurement point and the glycemia threshold above which a diagnosis of DM proves more likely in postpartum reassessment. We found glycemia≥189mg/dl recorded after 2h in the OGTT with 100g of glucose to be related to a greater probability of postpartum DM. The multivariate analysis adjusted for factors related to postpartum diabetes confirmed its association independently.

With regard to HbA1c determined during pregnancy, the literature describes an association with postpartum DM (RR: 2.56), but the evidence is weak.18 In our study we found that patients who were finally diagnosed with DM in the postpartum period had higher HbA1c concentrations during pregnancy than the other women. Our analysis found an HbA1c concentration of 5.9% or more at the diagnosis of GD to be very specific (95.9%) in predicting postpartum DM.

We consider our findings to be very important, since they may allow us to identify those women at an increased risk of developing DM after delivery, based on objective information drawn from the OGTT with 100g and HbA1c measurements during pregnancy. This may allow us to provide more firm recommendations for those patients at increased risk. On the one hand, adherence to testing in postpartum reassessment is indicated, and on the other hand adherence to the provided recommendations is needed in order to lessen the risk of future DM as far as possible.

It may therefore be concluded that in our sample of patients with GD, certain laboratory test parameters such as blood glucose at 2h in the OGTT with 100g or HbA1c measurements performed during pregnancy are related to the diagnosis of postpartum DM.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Civantos S, Durán M, Flández B, Merino M, Navea C, Guijarro G, et al. Factores predictores de diabetes mellitus posparto en pacientes con diabetes gestacional. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:83–89.