Preconception care has been shown to decrease the risk of pregnancy-related complications in women with diabetes, but many women do not plan their pregnancies. Our aim was to identify the associated factors and barriers related to the involvement of these women in preconception care.

Material and methodsFifty women with pregestational diabetes (28 with type 1 diabetes) and 50 non-diabetic pregnant women were consecutively enrolled at our hospital. They completed a questionnaire, and their medical histories were reviewed.

ResultsAll 33 patients with diabetes who received preconception care had a similar current age (34.3±5.3 years) and age at diagnosis (20.3±11.3) to those with no preconception care (n=17) (31.8±5.3 and 19.1±10.6 years respectively; p>0.1), but were more frequently living with their partners (97% vs. 70.6%; p=0.014), employed (69.7% vs. 29.4%; p=0.047), and monitored by an endocrinologist (80.6% vs. 50%; p=0.034), had more commonly had previous miscarriages (78.6% vs. 10%; p=0.001), and were aware of the impact of diabetes on pregnancy (87.5% vs. 58.8%; p=0.029). The frequency of preconceptional folic acid intake was similar in pregnant women with and without diabetes (23.8% vs. 32%; p>0.1).

ConclusionsPreconception care of diabetic patients is associated with living with a partner, being employed, being aware of the risks of pregnancy-related complications, having had previous miscarriages, and being monitored by an endocrinologist. Pregnancy planning is infrequent in both women with and without diabetes.

El control preconcepcional ha demostrado reducir el riesgo del embarazo asociado a la diabetes, pero muchas mujeres siguen quedando gestantes sin planificación previa. Nuestro objetivo fue identificar los factores predisponentes y las barreras relacionadas con la realización de control preconcepcional.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron, de forma consecutiva, 50 mujeres con diabetes pregestacional (28 tipo 1) y 50 gestantes sin diabetes que acudían a nuestro centro. Se les pidió que cumplimentaran un cuestionario y se revisaron sus historias clínicas.

ResultadosLas 33 pacientes con diabetes y control preconcepcional tenían una edad actual (34,3±5,3 años) y al diagnóstico de la diabetes (20,3±11,3 años) similares a las 17 pacientes sin control (31,8±5,3 y 19,1±10,6 años, respectivamente; p>0,1), pero estaban con más frecuencia viviendo en pareja (97% vs. 70,6%; p=0,014), laboralmente activas (69,7% vs. 29,4%; p=0,047), eran seguidas por un/a endocrinólogo/a (80,6% vs. 50%; p=0,034), habían tenido abortos previos (78,6% vs. 10%; p=0,001), y conocían la repercusión de la diabetes en el embarazo (87,5% vs. 58,8%; p=0,029). No hubo diferencias significativas en la toma de ácido fólico pregestacional entre las gestantes con y sin diabetes (23,8% vs. 32%; p>0,1).

ConclusionesEn las pacientes con diabetes, acudir a control preconcepcional se asoció con vivir en pareja, estar laboralmente activas, conocer el riesgo de complicaciones, tener abortos previos y ser seguidas por un/a endocrinólogo/a. Existe un bajo porcentaje de preparación de la gestación, también en el grupo sin diabetes.

The global prevalence of diabetes is approximately 8.3%,1 and the number of diabetic individuals is expected to double over the period 2000–2030. Although the prevalence of the disease is similar in males and females, there are comparatively more diabetic women,2 and the prevalence of pregestational diabetes has increased in recent years.3,4 A study published in 2016 found 1% of all pregnant women to have pregestational diabetes mellitus, and in the course of the 17 years of the study the prevalence was seen to have increased 162% in the case of type 1 diabetes and 354% in the case of type 2 diabetes.4 Diabetes has been shown to increase the risk of preeclampsia, assisted delivery, cesarean section, macrosomia, preterm delivery, fetal and perinatal death,5 and congenital malformations.5,6 Furthermore, from the perspective of psychological wellbeing, diabetic women are more often affected by anxiety and depression both during pregnancy and after birth.7 Pregnancy also has an impact upon diabetes, since it can favor specific vascular complications such as retinopathy8–10 or even interfere with regular diabetes treatment, the latter requiring adjustments due to variations in insulin requirements during pregnancy.11

There is evidence that women with diabetes who receive preconception care have better blood glucose control, and that their offspring suffer fewer congenital malformations and other serious adverse events such as fetal or perinatal death.12–14 In addition, they run a lesser risk of admission to a neonatal Intensive Care Unit, in comparison with patients who do not receive preconception care.12

A systematic review published in 2012 concluded that preconception care in diabetes lowers the risk of congenital malformations from 7.4% to 1.9%, and decreases the perinatal mortality rate by 66%. It has been estimated that a one-point increase in the HbA1c level in turn increases the risk of such complications by 5–6%.14 The timing of the start of pregnancy control is also important, since women who report during the first three months of pregnancy suffer a lesser incidence of adverse events such as preterm delivery or fetal death than those who first report for pregnancy control at a later date.15 Despite the established benefits of preconception control, many women with pregestational diabetes have unplanned pregnancies.16 In a study of 85 women, 59% had unplanned pregnancies, despite the fact that 68% of them were aware of the advisability of prior control.17

The objective of this study was to identify the predisposing factors and barriers related to preconception control visits in patients with pregestational diabetes seen at our center.

Material and methodsParticipants and procedureA cross-sectional, descriptive observational study was carried out at the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil de Gran Canaria (Spain), following approval by the local Ethics Committee. The patients were invited to participate when they reported for routine medical visits between November 2016 and January 2017. A total of 102 patients were informed of the purpose of the study and were invited to participate. We consecutively recruited 50 women diagnosed with pregestational diabetes and who reported to the pregnancy and diabetes and diabetic education clinics, as well as 50 pregnant women without diabetes reporting for control ultrasound evaluation (weeks 11–13 or 20–22). Patients diagnosed with gestational diabetes or who were diagnosed with pregestational diabetes during their current pregnancy were excluded from the study.

After being informed about the study, the participants signed the informed consent and received a questionnaire addressing the items described below. The information obtained was subsequently compared with the case histories.

MethodsQuestionnaire on sociodemographic data and information about preconception control and diabetesThe questionnaire was specifically developed for this study. It consisted of 32 questions addressing the following issues: marital status and support received from the partner regarding pregnancy, educational level and occupational status, toxic habits, frequency of physical exercise, previous diseases, use of contraceptive methods, and desire and planning of pregnancy. A second part focused on information regarding diabetes (type of diabetes, age at the time of diagnosis, complications, treatment, family history), patient knowledge of the consequences of diabetes in pregnancy, the relationship with the medical team supervising the diabetes, and the preconception advice received.

Other clinical variablesOther clinical variables not obtained through the questionnaire were collected from the patient case histories, and the data obtained from the questionnaire in turn were compared with the data contained in the case histories. The case history data were used in cases of possible contradiction. We recorded body weight and height at the start of pregnancy (or the most recent values at the time of data compilation in the non-pregnant women), and calculated the body mass index (BMI). Information was collected on previous pregnancies and concomitant diseases. In the patients with diabetes, we recorded the type of diabetes and the time of diagnosis, the HbA1c concentration corresponding to the first trimester (or the most recent value in the non-pregnant women), the professional who referred the patient to the clinic, and the existence of diabetes complications. In the case of the pregnant patients, we also determined whether they reported for preconception care or not. The patients were questioned and the case histories and electronic prescriptions were reviewed to evaluate the timing of folic acid administration.

Statistical analysisThe data were analyzed using the SPSS version 23.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A descriptive analysis of the groups was carried out. Quantitative variables were reported as the mean±standard deviation (SD), and qualitative variables as percentages (n). Two-by-two group comparisons were made, using the Student t-test for independent groups (quantitative variables) and the chi-squared test (categorical variables). Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

ResultsA total of 102 questionnaires were delivered, of which two were discarded (one not correctly completed and the other corresponding to a patient diagnosed with diabetes during her current pregnancy).

Diabetic patients with and without preconception careThe group of patients with diabetes comprised 21 pregnant women and 29 non-pregnant women reporting for preconception care. Only four of the 21 pregnant women had received preconception care, and of these only two became pregnant after receiving medical approval.

Comparison was made of the patients with diabetes, divided into women who were receiving or had received preconception care (n=33, 18 type 1 diabetes) and those not reporting for preconception care (n=17, 10 type 1 diabetes). The first group included four pregnant patients (3 type 1 diabetes) and 29 non-pregnant women who had visited at the time of the study.

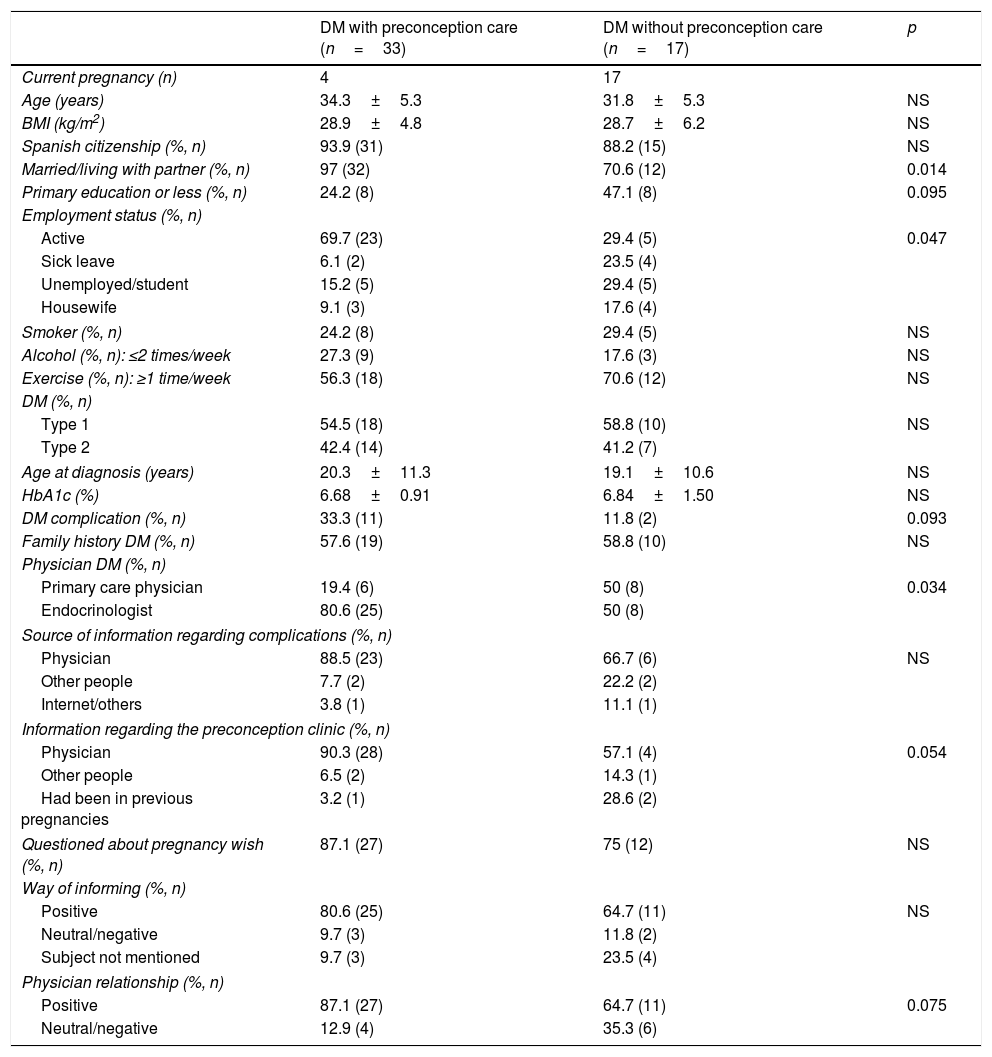

These patients did not differ in terms of age, the BMI or nationality, though there were differences regarding marital status and occupational status. The subjects with preconception care tended to have a higher educational level. Among these patients there were more actively employed subjects and women who were married or lived with their partner (Table 1).

Characteristics of the 50 diabetic patients with and without preconception care.

| DM with preconception care (n=33) | DM without preconception care (n=17) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current pregnancy (n) | 4 | 17 | |

| Age (years) | 34.3±5.3 | 31.8±5.3 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9±4.8 | 28.7±6.2 | NS |

| Spanish citizenship (%, n) | 93.9 (31) | 88.2 (15) | NS |

| Married/living with partner (%, n) | 97 (32) | 70.6 (12) | 0.014 |

| Primary education or less (%, n) | 24.2 (8) | 47.1 (8) | 0.095 |

| Employment status (%, n) | |||

| Active | 69.7 (23) | 29.4 (5) | 0.047 |

| Sick leave | 6.1 (2) | 23.5 (4) | |

| Unemployed/student | 15.2 (5) | 29.4 (5) | |

| Housewife | 9.1 (3) | 17.6 (4) | |

| Smoker (%, n) | 24.2 (8) | 29.4 (5) | NS |

| Alcohol (%, n): ≤2 times/week | 27.3 (9) | 17.6 (3) | NS |

| Exercise (%, n): ≥1 time/week | 56.3 (18) | 70.6 (12) | NS |

| DM (%, n) | |||

| Type 1 | 54.5 (18) | 58.8 (10) | NS |

| Type 2 | 42.4 (14) | 41.2 (7) | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 20.3±11.3 | 19.1±10.6 | NS |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.68±0.91 | 6.84±1.50 | NS |

| DM complication (%, n) | 33.3 (11) | 11.8 (2) | 0.093 |

| Family history DM (%, n) | 57.6 (19) | 58.8 (10) | NS |

| Physician DM (%, n) | |||

| Primary care physician | 19.4 (6) | 50 (8) | 0.034 |

| Endocrinologist | 80.6 (25) | 50 (8) | |

| Source of information regarding complications (%, n) | |||

| Physician | 88.5 (23) | 66.7 (6) | NS |

| Other people | 7.7 (2) | 22.2 (2) | |

| Internet/others | 3.8 (1) | 11.1 (1) | |

| Information regarding the preconception clinic (%, n) | |||

| Physician | 90.3 (28) | 57.1 (4) | 0.054 |

| Other people | 6.5 (2) | 14.3 (1) | |

| Had been in previous pregnancies | 3.2 (1) | 28.6 (2) | |

| Questioned about pregnancy wish (%, n) | 87.1 (27) | 75 (12) | NS |

| Way of informing (%, n) | |||

| Positive | 80.6 (25) | 64.7 (11) | NS |

| Neutral/negative | 9.7 (3) | 11.8 (2) | |

| Subject not mentioned | 9.7 (3) | 23.5 (4) | |

| Physician relationship (%, n) | |||

| Positive | 87.1 (27) | 64.7 (11) | 0.075 |

| Neutral/negative | 12.9 (4) | 35.3 (6) | |

DM: diabetes mellitus; BMI: body mass index; NS: non-significant (p>0.1).

A total of 94.4% of the patients receiving preconception care and 100% of those without such care claimed to be strongly supported by their partner, the percentages being similar (p>0.05). We likewise observed no differences with regard to smoking habit, alcohol consumption or physical exercise (Table 1) between the two groups.

No significant differences were recorded in the frequency of previous pregnancies between the groups with and without prior preconception care (42.4% [n=14] vs. 58.8% [n=10], respectively [p>0.05]), though differences were noted in relation to the frequency of previous miscarriages. Of the 14 women with preconception care who had experienced a previous pregnancy, 11 had suffered at least one previous miscarriage (78.6%), versus only one of the 10 patients without preconception care (10%) (p=0.001).

The pregnant women with and without prior preconception care did not differ in the frequency with which pregnancy was reported to be desired (100% [n=4 out of 4] vs. 82.4% [n=14 out of 17], respectively). There were no differences in terms of the type of diabetes, age at the time of diagnosis, HbA1c concentration or family history. The patients with preconception care tended to have more complications and were more often monitored by an endocrinologist, while the patients without preconception care were more often monitored in their primary care center (Table 1). Of the 50 diabetic patients, 62% (n=31) received regular insulin treatment, 20% (n=10) used oral antidiabetic drugs, 8% (n=4) received oral antidiabetic drugs and insulin, and 10% (n=5) received no drug treatment for diabetes. Twenty-four diabetic patients had other associated diseases, the most frequent being hypothyroidism (n=6), asthma (n=5), arterial hypertension (n=4), allergic rhinitis (n=3) and valve disease (n=2).

A total of 41.2% of the patients (n=7) that did not report to preconception care were aware of the existence of the clinic. Furthermore, 58.8% (n=10) knew about the repercussions of diabetes upon pregnancy, compared with 87.5% (n=28) of those who did report for preconception care (p=0.029). However, on questioning the patients who claimed to know about this risk (n=38) regarding the complications they were aware of, 26.5% described no complication or stated that they were unable to cite any complication. In turn, 12.2% (n=6) only stated that they thought there might be complications for the infant or for both the infant and mother, but failed to cite any concrete complication.

On questioning the pregnant patients who had not received preconception care (n=17) about why they had not undergone such care, 6 failed to answer, and of the 11 who answered the question, 7 claimed to not have reported for preconception care because the pregnancy had not been planned; two did not know that such care was needed or did not consider it necessary; and two replied that they had reported for preconception care, but did so when already pregnant.

The physician was the main source of information for the patients regarding both the complications and the existence of the preconception care clinic, particularly in the preconception care group (Table 1). Two patients who had not reported for preconception care claimed to be unaware of the clinic's existence, despite having visited it on the occasion of previous pregnancies.

A total of 33.3% (n=11) of the patients with preconception care were referred from the human reproduction unit; 27.3% (n=9) were referred by the endocrinologist; 24.2% (n=8) were referred by the clinic itself since they had already been seen on the occasion of previous pregnancies; and 9.1% (n=3) were referred from the primary care center. The corresponding information could not be obtained in two cases.

No significant differences were observed regarding the manner in which they were informed about diabetes and pregnancy or the frequency with which the physician asked them about their wish to become pregnant, though the women with preconception care tended to have a more positive relationship with the physician than those without preconception care (Table 1). With regard to the question of what they would change in the way of being informed by the physician about diabetes and pregnancy, 15 failed to give an answer, while of the 35 women that did answer, 80% (n=28) claimed that they would not change anything. Of the 20% of the patients (n=7) who stated that they would change something, 5 wished they had received more information; one would have liked a better explanation of the reasons why maintaining good blood glucose control is important; and another patient would have liked to have been informed of the existence of the preconception clinic. In relation to the relationship with the physician, of the 41 patients who answered the question about whether they could suggest changes, 90.2% (n=37) said they would not change anything; two would have liked the relationship to be closer; one would have liked the physician to pay more attention to her; and another would have liked more frequent medical visits.

Patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetesOf all the diabetic patients included in the study, 28 had type 1 diabetes, 21 had type 2 diabetes, and one patient had maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY). The type 1 diabetics were comparatively younger (31.7 [5.6] vs. 36.0 [3.9] years; p=0.003); had an earlier age at the time of diagnosis of diabetes (12.7 [6.8] vs. 29.9 [7.3] years; p<0.0005); were more obese (BMI 26.6 [5.1] vs. 31.9 [3.5]; p<0.0005); and had a higher educational level (university education in 46.4% vs. 10%; p=0.004) than the patients with type 2 diabetes. No significant differences were recorded in the frequency with which the patients lived with their partner, in occupational status, the frequency of previous pregnancies, or the HbA1c levels. Most of the type 1 diabetic women (85.7%) were routinely monitored by an endocrinologist. Most of the type 2 diabetic women were monitored in primary care (60%) and to a lesser extent by an endocrinologist (20%).

Most of the type 1 diabetic women who reported for preconception care had been referred by the endocrinologist (61.5%) or by the diabetes and pregnancy clinic itself (23.1%). The women receiving preconception care had a higher educational level (p=0.021) and were more often actively employed (72.2% vs. 30%, p=0.04) than those who failed to report for preconception care. The frequency of living with the partner was similar, however, and patient age, age at the time of diagnosis, and the BMI were also similar.

The type 2 diabetic women who reported for preconception care were more often referred by the reproduction unit (42.9%), where they had been seen due to infertility, or by the diabetes and pregnancy clinic itself (35.7%), where they had been monitored on the occasion of their previous pregnancy. The women who reported for preconception care were more often living with their partner than those who did not report for such care (100% vs. 57%; p<0.05). However, there were no differences in terms of patient age, age at the time of diagnosis, the BMI, educational level or occupational status.

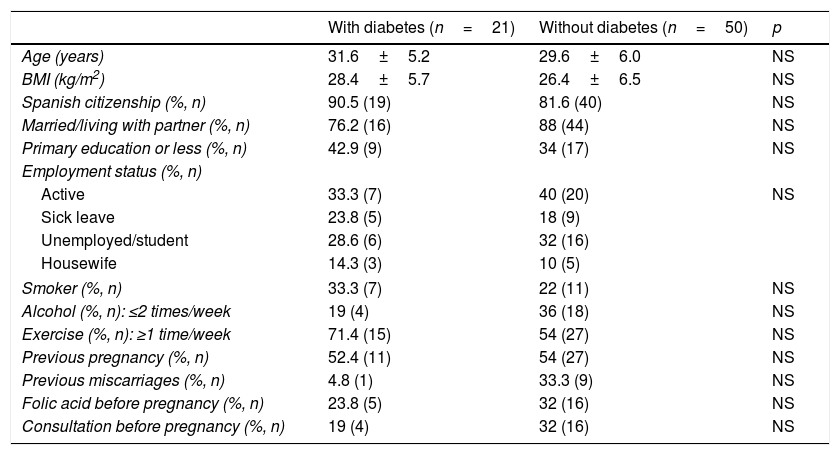

Pregnant patients with and without diabetesThe pregnant women with and without diabetes did not differ in terms of demographic data, the BMI, toxic habits or the frequency of physical exercise (Table 2). A total of 91.5% of the diabetic patients (n=43) felt strongly supported by their partner, and only 8.5% (n=4) considered that they lacked support. Similar results were obtained in the case of the pregnant women without diabetes (94.7% [n=18] and 5.3% [n=1], respectively; p>0.05). Likewise, no differences were observed in relation to previous pregnancies or miscarriages, the use of folic acid, contraception, the wish to become pregnant, or medical visits before pregnancy. The percentage use of folic acid before pregnancy was low in both groups of patients (Table 2). A total of 85.7% (n=18) of the diabetic patients and 80% (n=40) of the pregnant women without diabetes claimed pregnancy to have been desired (p>0.05).

Comparison of pregnant patients with and without diabetes.

| With diabetes (n=21) | Without diabetes (n=50) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.6±5.2 | 29.6±6.0 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4±5.7 | 26.4±6.5 | NS |

| Spanish citizenship (%, n) | 90.5 (19) | 81.6 (40) | NS |

| Married/living with partner (%, n) | 76.2 (16) | 88 (44) | NS |

| Primary education or less (%, n) | 42.9 (9) | 34 (17) | NS |

| Employment status (%, n) | |||

| Active | 33.3 (7) | 40 (20) | NS |

| Sick leave | 23.8 (5) | 18 (9) | |

| Unemployed/student | 28.6 (6) | 32 (16) | |

| Housewife | 14.3 (3) | 10 (5) | |

| Smoker (%, n) | 33.3 (7) | 22 (11) | NS |

| Alcohol (%, n): ≤2 times/week | 19 (4) | 36 (18) | NS |

| Exercise (%, n): ≥1 time/week | 71.4 (15) | 54 (27) | NS |

| Previous pregnancy (%, n) | 52.4 (11) | 54 (27) | NS |

| Previous miscarriages (%, n) | 4.8 (1) | 33.3 (9) | NS |

| Folic acid before pregnancy (%, n) | 23.8 (5) | 32 (16) | NS |

| Consultation before pregnancy (%, n) | 19 (4) | 32 (16) | NS |

NS: non-significant (p>0.1).

The present study carried out in women with pregestational diabetes to establish predisposing factors and barriers against preconception care has identified a series of social factors, parameters regarding disease and previous experience, as well as variables more dependent upon the healthcare system. The patients with preconception care were more often actively employed, lived with their partner, and had a higher educational level than those without preconception care. They also showed a higher incidence of previous miscarriages and greater knowledge of the risks of pregnancy, and tended to have more diabetes complications. The patients with preconception care were also more often monitored by an endocrinologist and were more likely to have a positive relationship with their physician.

With regard to the strengths of our study, mention must be made of the fact that it included both diabetic women with and without preconception care and women without diabetes. All of them were enrolled on a consecutive basis, without a selection process. Moreover, we not only studied clinical parameters related to the disease but also included questions where the patients expressed their knowledge of diabetes, their reasons for not visiting the physician before becoming pregnant, and how they perceived the physician.

With regard to the social factors, other studies have also described a relationship between the use of folic acid and the intention to secure good blood glucose control before pregnancy, and the fact of working outside the home or of being married.17,18

A large proportion of the diabetic patients had a degree of knowledge about the impact of diabetes upon pregnancy, in concordance with the findings of other studies.19,20 In a study involving 29 women with pregestational diabetes and previous pregnancies without preconception care, 90% were found to have some knowledge of the risks of diabetes during pregnancy. Of the 14 who had undergone previous pregnancies, 12 of them had experienced complications. However, these previous complications were not necessarily attributable to a lack of preconception care, and they did not seem to motivate them to request preconception care in subsequent pregnancies.20 This was also seen in another study in which women with previous pregnancies and complications were more likely to again become pregnant with poor blood glucose control.21 However, in our study we found a greater percentage of miscarriages and a tendency to suffer more diabetes complications among the patients reporting to preconception care than among those who did not. The former largely consisted of women who, following the adverse outcome of an ongoing pregnancy directly made an appointment with the same diabetes and pregnancy clinic to plan the next pregnancy.

Women with diabetes have a broad range of concerns during pregnancy, and this causes greater stress than in patients without diabetes, with more depression and poorer mental health.7 The information supplied by the physician sometimes exacerbates these concerns when the conveyed message proves disheartening, inadequate or inexact. In contrast, those women who feel supported and receive recognition of their efforts experience fewer negative emotions. Improved patient psychological wellbeing therefore requires not only the support of the family, but also that of the healthcare professionals.7 We recorded no differences in the level of support received from the partner or in the information received from the physician managing the diabetes between those patients who planned pregnancy and those who did not, although the women receiving preconception care tended to have a better relationship with their physician, in agreement with the observations of other authors.17,22 Likewise in agreement with our own findings, other studies have found diabetic patients who undergo preconception care to be more often monitored by an endocrinologist.17

Other articles have reported blood glucose control to be significantly better among the patients with preconception care,23 though this was not observed in our study. This may be explained by the fact that our preconception care group included non-pregnant women who at the time of the study had not yet received the go-ahead to become pregnant. In fact, of the few pregnant women who reported for preconception care, one-half had become pregnant before receiving medical approval. The profile of the patient reporting to our preconception care clinic was that of a woman with type 1 diabetes controlled by an endocrinologist, or a woman with type 2 diabetes and infertility, referred from the human reproduction unit. Only a minority were type 2 diabetics monitored by primary care.

In our study, both the women with diabetes and those without presented very low pregnancy planning rates. Only 23.8% of the diabetic patients and 32% of the non-diabetic pregnant women were taking folic acid before becoming pregnant. This may suggest that greater health education efforts are needed in the global population – not only in patients with diabetes. In fact, a low use of folic acid has been reported in other populations. In an Australian study involving 588 pregnant women, only 23% had used folic acid at least one month before becoming pregnant,24 while in another study of 782 pregnant women in Valencia (Spain), only 19.2% had used folic acid.25 Other studies have recorded somewhat higher percentages, such as among 1173 women in London (51%),26 or in another study carried out in Switzerland.27 The latter publication documented an increase in preconception folic acid intake between the periods 2000–2002 (27.5%) and 2009–2010 (40.7%).27

To sum up, in our study the patients with preconception care were more often actively employed, lived with their partner, and tended to have a higher educational level, none of them factors amenable to influence by the healthcare professional. However, it is possible to improve the patient-physician relationship and to better inform women of childbearing potential, whether they have diabetes or not. Furthermore, the low percentage of patients referred from the primary care setting suggests that a greater involvement on the part of primary care may be needed for educating and referring patients with diabetes before they become pregnant, as well as for promoting preconception folic acid use.

We are aware that our study has some limitations. Firstly, because of the short recruitment period, we only had a small patient sample; in this regard, although not a selected sample, it might not be representative of the served population as a whole, and comparisons between groups are complicated. Secondly, the questionnaires were given to the patients who completed them in the waiting room before entering the consulting room, sitting alongside other patients or persons accompanying them, and this may have influenced the high reported percentages of desired pregnancies and the claims of strong support from their partner. Moreover, only a minority of the patients with preconception care were pregnant. Due to the low frequency with which our pregnant patients had undergone preconception care, this was the only way to ensure a significant representation of this group. Another limitation was the difficulty of comparing some of the information obtained from the questionnaires with the case histories, particularly in non-diabetic patients, where not all the study variables were documented.

ConclusionsThe present study involving women with pregestational diabetes has established an association between preconception care and living with a partner, being employed, knowledge of the risks of complications if pregnancy is unplanned, previous miscarriages, and being monitored by an endocrinologist. However, the cross-sectional design of the study did not allow us to determine a causal relationship. The percentage preconception use of folic acid was low in both the patients with and without diabetes.

Financial supportNo specific funding was received for this study. However, in the course of the study the investigators received funding from the Agencia Canaria de Investigación, Innovación y Sociedad de la Información (DA-M, pre-doctorate grant), V Ayuda Guido Ruffino for Research in Therapeutic Education in Diabetes of the Sociedad Española de Diabetes in 2015 (DA-M, AMW), and from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI 16/00587; BV, AMW).

AuthorshipAll the authors contributed to the study design and reviewed and approved the final manuscript version. SC was in charge of data compilation and analysis, and prepared the first manuscript draft; SC, BV and AMW reviewed the case histories and the electronic prescriptions of the participants.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they are aware of no conflicts of interest in relation to the contents of this article.

Thanks are due to the nurses Alicia Merino, Aquilina López and Carmen Fleitas for their help in relation to patient recruitment. We also thank all the patients who participated in the study.

Please cite this article as: Carrasco Falcón S, Vega Guedes B, Alvarado-Martel D, Wägner AM. Control preconcepcional en la diabetes: factores predisponentes y barreras. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:164–171.